By William McPeak

The fundamental pillars of war—strategy and tactics— inevitably depend on an imponderable and uncontrollable factor: the weather. With the increasing sophistication of weather data gathering, analysis, and forecasting in the early 20th century, predicting the weather became an integral part of World War II. Just how integral such predictions were was brought home to Germany after its initial thrusts at the beginning of the war in 1939.

The Allies launched a concerted effort to keep comprehensive weather data from the Nazis by blacking out the international exchange of weather data through open radio transmission. For Europe, the most important geographical area for data gathering was the wintry expanse of the Arctic, from which location stormy weather moved east and south. The vital data from Arctic stations, extending from Greenland to the Siberian Sea via Svalbard and Franz Josef Land, were almost completely cut off after these stations were progressively blacked out and deactivated by the Allies. The British went a step further, broadcasting bogus weather data into Germany.

Meteorology and Grand Strategy

Germany needed to act aggressively to defeat the data-gathering war. In January 1940, the German Naval Meteorological Service took the first steps in laying down a data grid network of its own to provide regular weather observations. Various trawlers and sealers were converted into weather observation ships to collect and transmit accurate weather data from Iceland northward to the east coast of Greenland and on to Spitzbergen. The Allies quickly realized what the ships were doing and attacked them mercilessly.

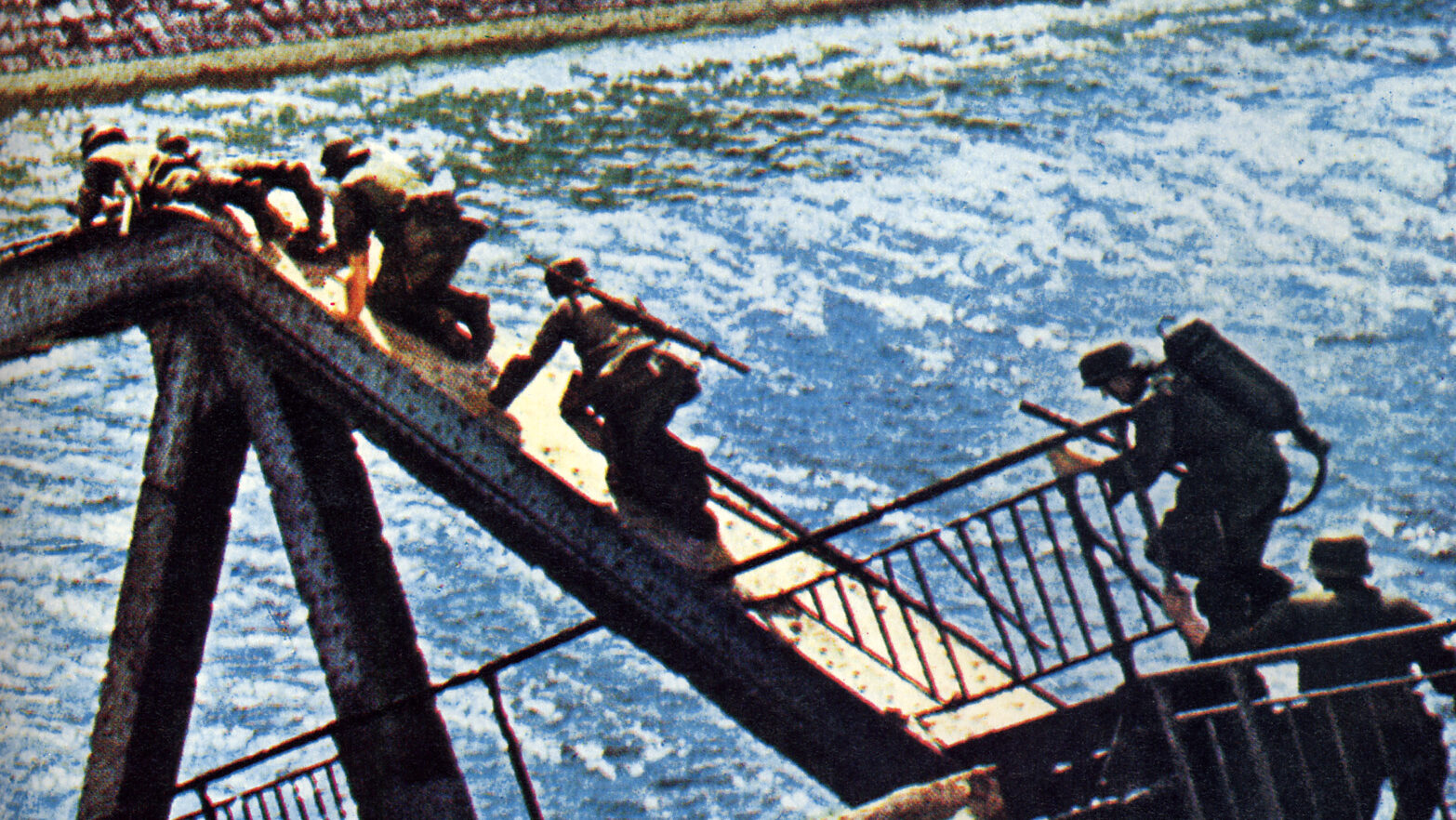

The Luftwaffe decided on its own course of action, establishing long-range weather reconnaissance flights and manned and automatic weather stations in the Arctic regions. Both naval and air force plans came under the grander strategy of securing continental Europe by the Third Reich. The refusal of a nonaggression pact by Denmark and Norway sealed their eventual fate. They were too militarily and meteorologically strategic, especially the long western coastline of Norway, to be left to their own devices. On April 9, 1940, German air and sea forces descended on both Scandinavian countries. Denmark was taken quickly, but the Norwegian rough terrain required further logistics. Despite the delays provided by the valiant Norwegian resistance, by late April Norway was secured, and the Nazis began constructing defenses along the fjord-clogged western Norwegian coastline.

The Wekusta is born

The most efficient means of gathering weather data over the North Atlantic and Arctic expanses was through air reconnaissance. The Weather Service of the Luftwaffe prepared a special weather reconnaissance unit to collect weather data, the Grossraum Wettererkundungsstaffel—Wekusta for short. With the progression of the war, Wekusta squadrons would branch out along German borders, a total of 12 squadrons with nearly 1,000 flight crews.

The demands on long-range weather recon programs were significant. To begin with, data gathering required reliable twin-engine planes. Prior to the war, the production of the German twin-engine bomber class had been cloaked behind designs for passenger planes and mail and cargo planes. German airplane manufacturers built planes that could be easily converted to bombers. By the mid-1930s, leading German airframe makers were developing three such twin-engine, low-wing planes: the Dornier Do-17, the Heinkel He-111, and the Junkers Ju-88.

The Luftwaffe converted all three from medium-range bombers into photo and other recon applications. All had structured metal that provided some armor protection for withstanding light machine-gun fire, along with self-sealing fuel tanks for long-range missions. The Do-17 carried a tightly fitted three-man crew, while the larger Ju-88 carried four crewmen and the He-111 carried five. Since the reconnaissance planes worked alone, defensive weaponry was essential. The Wekusta planes had progressively better models of machine guns placed in the nose and rear cockpit, along the sides, and the ventral underneath.

Building the Wekusta

Wekusta airstrips began appearing along the northern German coastline. By February 1940, a Wekusta base had opened at Oldenburg, near the port of Bremen, with a He-111 H-2 and a Do-17Z. With Norway already secured, another Wekusta base opened at Bad Zwischenahn in May 1940. Initially, it had a lone He-111, but the Heinkel was joined by a Ju-88. As the most recently designed reconnaissance aircraft, the Ju-88 had an increased wingspan and lengthened ailerons for better control. Junkers could not mass produce its powerful 211J engines (1,340 hp) until late 1940, so the new airframe had to rely on 211B-1 engines (1,210 hp). The interim model was designated as the Ju-88 A-5 and was quickly put into mass production.

By later April 1940, routine Luftwaffe weather reconnaissance was under way in Norway from the farthest western base at Stavanger, southwest of Oslo. Norway was the essential springboard for gathering North Atlantic and Arctic meteorological data. Wekusta flights were considered of the utmost importance, scheduled for the same time every day, even in bad weather, to keep a continuous record of weather analysis.

Other Wekusta planes flew out of Oldenburg, Germany, on a scheduled daily nine-hour trip northwest to the Faeroe Islands, passing near Fair Isle off the Scottish coast and between the Orkney and Shetland Islands. With the expansion of British radar sites, these flights flew low to avoid radar and hostile encounters—standard altitude was only 30 to 50 feet above the ocean. Taking basic weather readings (pressure, wind, and temperature), they reached the Faeroes, then climbed to about 22,000 feet to take a vertical cross-section of weather data for transmission over shortwave radio during the return trip. The squadron’s insignia was a profile of Fair Isle with a rainbow overhead.

Werner Schwerdtfeger

Wekusta crews were a game lot, singularly dedicated to manning lone planes and flying over thousands of miles of cold northern ocean. Crew size depended on the plane, but there was always a pilot and a meteorologist with radio experience to transmit data if a radioman was not along. Usually there was a gunner-mechanic as well. The larger He-111 would often carry an additional backup radioman—such was the vital importance of transmitting the data. One of the meteorologists was Werner Schwerdtfeger, who had received his doctorate at the University of Leipzig’s Geophysical Institute in 1931. Schwerdtfeger was no stranger to collecting aerial weather data. Between 1932 and 1934, he manned a balloon with an instrument-filled gondola, frequently drifting up to 8,000 feet in altitude. Schwerdtfeger’s interest in polar weather turned him to the military, and he trained in weather reconnaissance for Wekusta between 1936 and 1940.

Schwerdtfeger soon moved on to an even more essential weather squadron, Wekusta 5, which was activated in May 1940 at Trondheim, Norway, 300 miles north of Stavanger. Trondheim would be the primary base for all weather recon

flights westward and northwest. Auxiliary airstrips opened 600 miles farther north at Banak in November 1941. The new route took an initial leg to the Faeroe Islands, then headed west to the southern tip of Iceland. A second route flew northwest to the Jan Mayen Islands and due east to Banak. The various auxiliary strips could mean life or death for Wekusta flights returning from the Arctic and all its perils.

Eventually Wekusta 5 would total 142 flight personnel, and Schwerdtfeger was not the only Ph.D. in meteorology. Of the 43 crew members classified as meteorologists, 15 were doctors of science. The men of Wekusta 5 adopted a rather comical winged leaping frog as their squadron badge. They had an interesting initial mix of early planes: He-111, Do-17, Ju-88, and some oddities including two Ju-52s (an older three-engine cargo plane) and a He-60 two-seat bi-wing seaplane for shorter reconnaissance trips.

The Allies Crack Down

By late 1940 and early 1941 recon losses had increased dramatically. The regular flights of “Weather Willies,” as locals nicknamed the Wekusta units, were quickly recognized by British intelligence. On January 12, 1941, a Do- 215 crashed with all aboard on a small island off Scotland after being intercepted by members of the British Hurricane Squadron No. 3 posted to Sumburgh in the Shetlands. Three days later, one of the few Ju-88s (A-5) allotted to Wekusta was intercepted 10 miles north of Fair Isle but managed to escape, aided by its faster speed.

Two days later, an He-111 H-2 was caught by two Hurricanes near Fair Isle. The H-2 pilot, Lieutenant Karl Heinz Thurz, just 21 years old, had been fighting snow flurries across the North Sea at the usual wave-skipping height when increased snowfall forced him to climb to 8,000 feet. British radar immediately picked him up at that time, and Thurz spotted Hurricanes below him as he headed for the clouds. The British followed, strafing the length of Thurz’s fuselage and hitting the engines. Thurz climbed into the clouds and lost them, but his problems had just begun. Turning east to attempt a return to Norway, Thurz’s starboard and port engines began to smoke—there was no going home. He headed for a crash landing on Fair Isle. He came in too fast, bounced on the rough terrain, and forced the reluctant ship down by a hard rudder maneuver. The tail section broke apart at impact, throwing crewmen Leo Gburek and Georg Nentwig to their deaths. The three other crewmen escaped the wreckage before the engines caught fire, but were taken as POWs by island residents.

More casualties were to come. Three days later, an H-5 had to make an emergency landing in the Storskarvan Mountains near Vaernes, with injuries to the pilot and meteorologist. Two weeks later, on February 8, another Wekusta H-5 was mistakenly strafed by a Luftwaffe Bf-110 fighter, wounding one crew member.

Expanding the Wekusta

The expansion of Wekusta flights became essential after the Allies destroyed Arctic coal mines and installations on the Svalbard archipelago, forcing the closure of the precious Norwegian weather stations on Spitzbergen and Bear Island during the summer of 1941. From the north, Germany was completely weather-blind. Although two manned stations were set up and resupplied by ship and air drop, Wekusta reconnaissance north and northeast became uppermost. In July, the most veteran of the “weather fliers,” as Schwerdtfeger called them, 1st Lieutenant Rudolf Schütze of Wekusta 5, made the first flight over the Barents Sea from Banak to Novaya Zemlya in the Soviet Union in an H-5. Since 1931 Schütze had logged some 5,000 weather flights as the central pathfinder in reconnaissance routing of the Arctic.

Arctic weather regularly played havoc with Wekusta recon. The magnitude of winter storms and the deep winter darkness lasting from early November into February grounded flights until daylight returned in late winter. Uninterrupted data transmission during these months came from two automatic stations replacing the manned Spitzbergen stations in 1942. The automatic stations covered the intense winter period with weather sensor data transmitted by shortwave in encoded Morse letters. With the onset of Allied shipping support to Russia, the Germans made a valiant effort but fell short in expanding their automatic and manned stations.

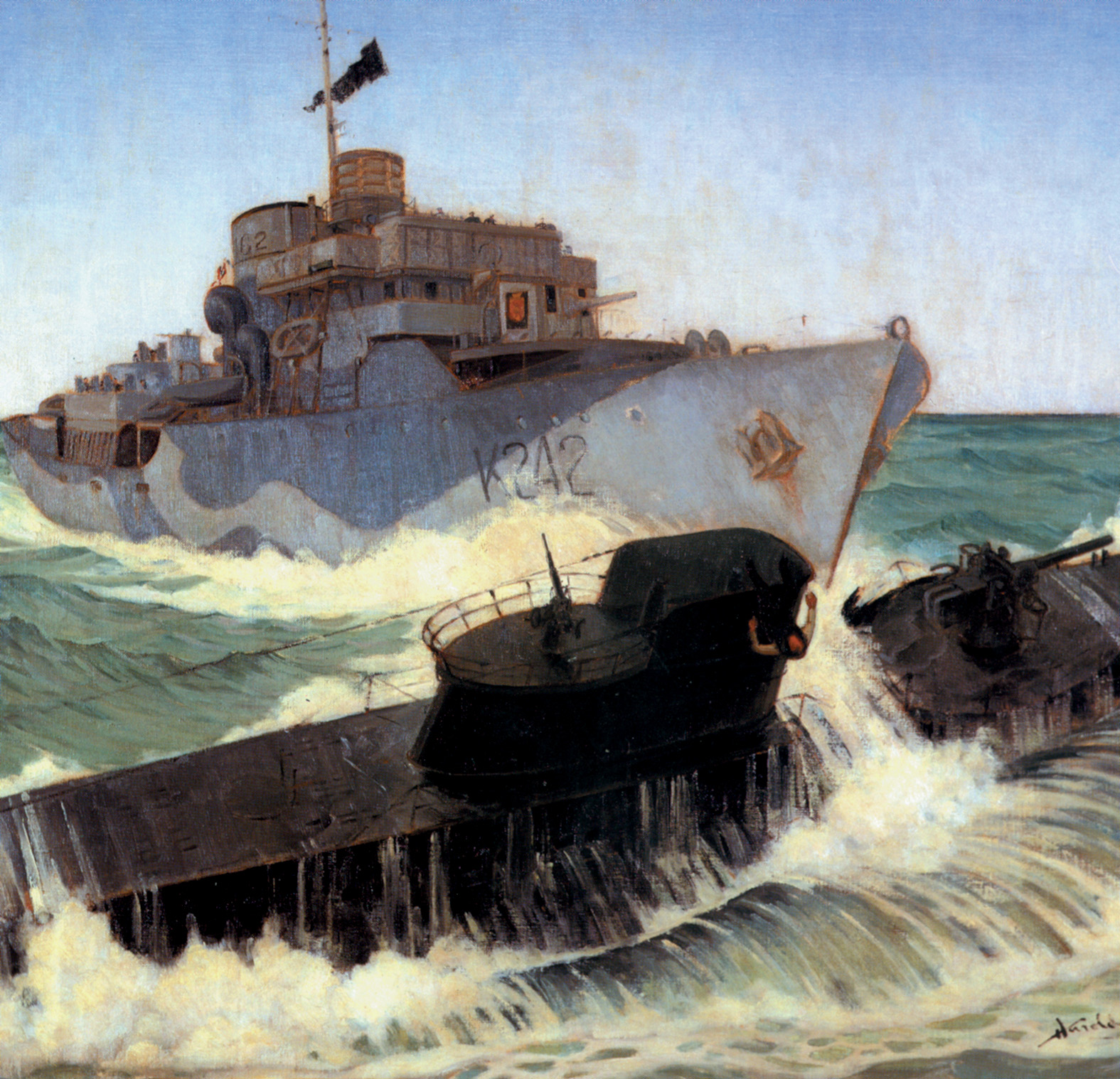

Wekusta opened two new routes out of Banak, one west and one east of Spitzbergen. With the buildup of the forward auxiliary detachment at Banak, several Wekusta 5 personnel were posted there. Schütze became the first to land at Novaya Zemlya, the northeasternmost destination for weather recon. Among manned stations from Greenland eastward, the farthest northern station was located at Alexandra Land (above 80 degrees north) in the fall of 1943. Logistical problems necessitated the use of sea planes and U-boats, and weather recon flights were further reduced when Wekusta planes were transferred to combat squadrons to meet the Allied push in the Mediterranean.

A new, long-range recon version of the Ju-88 D-1, equipped with the same big Junkers J engine and bigger fuel tanks, reached Wekusta units toward the end of the year. The new plane reflected the necessity to fly the more risky and strategically essential Arctic reconnaissance routes with more reliable planes. The D-1 would become the main recon ship, its chief advantage being that it was faster and more maneuverable than the H-5. Even with the improved aircraft, Wekusta units continued to lose crews. Laconic but telling log entries such as “emergency landing at sea,” “lost at sea,” or “crashed at sea” recounted the losses. In the frigid Arctic waters, survivors without an onboard inflatable life raft counted their lives in minutes, not hours.

New Roles, Dwindling Supplies, More Losses

Between 1943 and 1945, Wekusta 5 was also a source for intelligence and ice recon as well as supplies for weather stations at Greenland, Spitzbergen, and islands north. The forward base at Banak welcomed a new weather recon squadron, Wekusta 6, in October 1943. At Stavanger, Wekusta 1 split, forming another squadron, Wekusta 3, in January 1944. All squadrons felt the downturn in supplies late in the war when they lost planes, personnel, and fuel allotments to combat units. As a result, Wekusta flight schedules were gradually restricted and eventually planes flew only on urgent notice.

Casualties might have been expected to fall, but unrelenting nature—not enemy fire—continued to claim victims. In 1943 Wekusta 1 lost four D-1s and a D-5. Wekusta 5 lost an H-6, a D-1, and an Arado 232A boom-tailed, boxcar transport, this last marking the loss of Rudolf Schütze, who crashed on a mountainside in Porsanger Fjord off the coast and near Namsos, Norway, after takeoff on August 26. Short-lived Wekusta 6 lost only a D-1 and a bigger-engine H-16 in 1944, while its parent squadron, Wekusta 5, lost three D-1s. The shorter-lived Wekusta 3, in less than a year of operation, lost five Ju-88s of various sorts, one being shot down by mistake by a German U-boat. They also lost one of the new Ju-188s (bubble-nose cockpit and increased fuel storage). Wekustas 1 and 3 carried on into the first two months of 1945, losing a Ju-88 G-1, a night fighter version, and a Ju-188.

By May 1945, Wekusta aircraft were performing evacuation tasks as the war drew to a close and the air and ground crews of the Norwegian Wekusta squadrons headed home. Some 120 would never return. Werner Schwerdtfeger was a surprising survivor, having flown hundreds of flights. Like many others with technical backgrounds and few opportunities in postwar Germany, he immigrated to Argentina, where he worked as a meteorologist. In 1963 he was invited to join the University of Wisconsin Meteorology Department, and he continued his celebrated career in polar meteorology. In 1982 he published a book, Weather Flier in the Arctic, recounting the exploits of Rudolf Schütze and other Wekusta comrades from the now-distant past, when risking all for the sake of a weather report was simply part of the daily routine.

Originally Published December 2009

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments