by Pat McTaggart

In the fall of 1942, in a prelude to the now-famous Operation Uranus, the Red Army had its back to the wall once again. During the first six months of the 1941 German invasion of the Soviet Union, the Wehrmacht had killed or captured almost three million Russian soldiers. December brought the Soviet Winter Offensive, which sent the German Army reeling back at the cost of another million Russian dead.

Hitler Takes Aim at the Oilfields in the Caucasus

Overextended Soviet supply lines, coupled with the onset of the spring thaw, brought the offensive to a halt, allowing both sides to regroup. As replacements and reinforcements rushed to the front, Adolf Hitler began planning a new offensive that he hoped would economically strangle his communist enemy. Codenamed “Blau” (Blue), the offensive was aimed at seizing the oilfields in the northern Caucasus and establishing a defensive line running along the Don River from Stalingrad to Voronezh. The move would deprive the Russians of valuable oil and, at the same time, provide that much needed commodity to the German armed forces. It was an ambitious plan—one that would stretch German armies in southern Russian to their limit. To bolster the German attack forces, Hitler called upon his Italian and Romanian allies to supply divisions for the offensive. In response, Mussolini ordered his 8th Italian Army to participate while Romanian dictator Ion Antonescu offered the 3rd and 4th Romanian Armies. Hungary and Slovakia also contributed to the cause.

The Soviets’ Disastrous Results

Stalin had ambitious plans of his own. In mid-May, he ordered the Red Army to recapture Kharkov, which had been under German control since the previous fall. The offensive was a disaster, costing the Russians almost 300,000 casualties and shattering five Soviet armies. As the Russians reeled from this latest defeat, preparations went forward for Blau, with orders being sent out to corps and division commanders detailing their part in the operation. For the Russians, the Kharkov offensive was another blow for an army still trying to find its way in the Blitzkrieg era. From Stalin downward, commanders had made mistakes costing millions of lives. By mid-1942, the situation seemed like it would not improve in the foreseeable future. In the far north, the Germans were advancing on Murmansk. Leningrad was besieged and starving, and a German salient around Rzhev was only about 150 miles from the Kremlin. In southern Russia, the Kharkov offensive had failed and the Crimean port of Sevastopol was almost certain to fall within a few weeks. Now it appeared that the Germans were grouping for a southern offensive of their own, and staff and intelligence officers in Moscow were working day and night trying to figure out where and when the Germans would strike.

Operation Blau’s Plans Fall into the Soviets’ Lap

For once, the Fates intervened on the side of the Soviets. On June 19, nine days before Blau was scheduled to begin, Major Joachim Reichel, the chief of operations of the 23rd Panzer Division, was flying back to his divisional headquarters after an aerial inspection of the front. His light aircraft, a Fiesler Storch, either developed engine problems or ran into turbulent weather. Whatever the cause, the Storch went down, forced to land behind the Russian lines.

Against orders that forbade classified material being taken into the forward areas, Reichel had kept the operational orders for Blau in his briefcase when he took off on his inspection flight. As he frantically tried to burn the briefcase, a Russian patrol appeared. Reichel’s fate is not known, but less than an hour later the plans were sitting in front of the commander of the 76th Rifle Division.

It was all there—orders of battle, divisional operational plans, maps, and timetables. The gold mine of information made it quickly up the chain of command. Army and Front commanders gleefully waited for orders from Moscow concerning how the information could be used, but they were sorely disappointed. When news of the find reached Stalin, he dismissed the papers as either forgeries or a deception plot. He had the plans for Blau, and he did nothing.

On the German side, Hitler was furious when told about the debacle. Several officers were sacked, and an air of uncertainty spread through the German high command. Did Reichel manage to destroy the documents or were they now in Soviet hands? No one knew. Nevertheless, Hitler was determined to achieve his goal. The offensive would not be called off.

Hitler Green Lights Blau, Then Changes the Plan

Blau began on June 28 with Generaloberst (Colonel General) Maximillian Freiherr von Wiechs’s 2nd Army and Generaloberst Hermann Hoth’s 4th Panzer Army advancing on Voronezh. On June 30, General Friedrich Paulus’s 6th Army began its attack to clear the Donets corridor. The Soviets fell back in disarray, suffering heavy casualties as they retreated.

In mid-July, Hitler astounded his commanders by assigning more objectives for the offensive. He divided the powerful Heeresgruppe Süd (Army Group South), his main attack force, into Heeresgruppe A (Field Marshal Wilhelm List) and Heeresgruppe B (von Weichs), and set a new list of priorities. List, with the 11th Army, 17th Army, and the 1st Panzer Army, was ordered to take all the oilfields north of a line running from Batumi, near the Turkish border, to Baku on the Caspian Sea. Von Weichs’s Heeresgruppe B (2nd Army, 6th Army, and 4th Panzer Army) was still assigned the mission of establishing a protective flank along the Don River, but Paulus was given one more objective for his 6th Army: capture Stalingrad!

Hitler had hardly mentioned the city before July, but the idea of capturing a great industrial center named for his arch enemy slowly became a fixation. In designating Stalingrad as a major objective and adding objectives in the Caucasus, the Führer had upset the operational planning of his entire southern front.

To accomplish his new plan, Hitler diverted Hoth’s 4th Panzer Army south to help in the Caucasus operation and to protect Paulus’s right flank, leaving a weakened Heeresgruppe B to continue slugging it out with the Russians in the Donets corridor. Despite Hitler’s meddling, von Weichs’s troops continued to press forward. In the south, Rostov was taken, allowing the motorized and panzer divisions of Heeresgruppe A to drive a deep wedge into the Caucasus.

Hitler Fixates on Capturing Stalingrad

Hitler was ecstatic as he read List’s reports, but he grew increasingly impatient about von Weichs’s operations in the north. He complained about the slow progress in reaching Stalingrad, conveniently forgetting that he had stripped most of the motorized divisions from Heeresgruppe B. Growing more anxious, he made another astounding move by ordering the 4th Panzer Army to disengage in the northern Caucasus and return north to help in the drive to the Volga.

The order angered both List and Generaloberst Franz Halder, the chief of staff of the German Army. When they protested to Hitler, he dismissed them both, personally taking command of Heeresgruppe A. Other commanders cautiously brought up the fact that the drive on Stalingrad, coupled with the enlarged Caucasus operation, was dangerously stretching the German flanks to the limit.

Hitler dismissed the danger, reminding his generals that the Italians, Romanians, and Hungarians were on the way. He assured them that these reinforcements could handle the flanks while German forces pursued their objectives. It was an amazing statement, considering the quality of the men and equipment that would be tasked with guarding those flanks.

The equipment in the three allied armies was mostly obsolete, some dating back to World War I. Much of the artillery was horse-drawn, and heavier caliber weapons were sorely lacking. Officers in the Romanian and Italian Armies generally treated their men as ignorant peasants, and there was a vast difference in lodging and dining privileges between those that gave orders and the common soldier.

Although allies of Germany, Romanian and Hungarian units could not co-exist on the same sector of the front. Age-old religious and ethnic rivalries remained ingrained, and the two sides could just as easily open fire against each other as they would on the Russians.

The Battle for Stalingrad Begins

When reviewing all these factors—Hitler’s meddling, dubious allies, and an increasing list of objectives—it seems incredible that the Wehrmacht made it as far as it did in the fall of 1942. On August 23, Paulus reached the Volga north of Stalingrad, and the battle for the city began in earnest. The 2nd Army had taken Voronezh, establishing a bridgehead on the eastern bank of the Don, and Heeresgruppe A continued its drive south, reaching the Kuban River and heading for the Caucasus oil wells.

The void left by these operations was filled by the arriving allied armies. With the 6th Army, assisted by elements of the 4th Panzer Army, engaged at Stalingrad, General Petre Dumitrescu’s 3rd Romanian Army (two cavalry and eight infantry divisions) took over a defensive line northeast of the city that ran for about 90 miles along the Don River. To his right was General Giovanni Messe’s 8th Italian Army, which formed a wedge between the Romanians and the 2nd Hungarian Army.

General Constantin Constantinescu’s 4th Romanian Army (two cavalry and five infantry divisions) was thrown in south of the city. It occupied a line running approximately 170 miles from Straya Otrada to Sarpa.

Georgi Zuhkov: Miracle Worker

The dispositions of the allied armies were a clear invitation for disaster. Stalin had already ordered that Stalingrad be held at all costs, but the meat grinder was destroying units almost as fast as they could make their way into the city. He needed a miracle to break the stranglehold at Stalingrad, and he found his wizard in the person of Marshal of the Soviet Union Georgi K. Zhukov.

Born in 1896, Zhukov was conscripted into the Army at the beginning of World War I. In 1918 he joined the Red Army. For more than 20 years, he served in the Red Army’s cavalry and armored forces until joining the Soviet high command in 1939. Escaping the purges that ravaged the Red Army in the 1930s, Zhukov was sent to the Far East, where the Japanese had already made two incursions into Soviet territory the previous year.

In May 1939, the Japanese struck again and drove toward the Khalkin Gol River. Fighting raged for four months until a counterattack, led by Zhukov, encircled and all but annihilated the Japanese 6th Army. Zhukov’s meteoric rise to fame was assured as a result of the victory.

As chief of the general staff, Zhukov was involved in organizing western Russian defenses in early 1941. When the Germans struck in June, he helped organize the defense of Leningrad. He was also instrumental in developing the plans for the Soviet winter offensive that drove the Germans back from the gates of Moscow.

In August 1942, with the Germans fast approaching Stalingrad, Zhukov was made deputy supreme commander of the Red Army. His plan to save Stalingrad was to trade land for blood. The longer the Germans had to fight for each mile of Soviet territory, the more time he had to gather reinforcements for the signature counterattack that had already brought him fame. He was willing to take enormous losses to achieve his goals, and he made no excuses for his actions.

Zhukov’s cold-blooded approach to warfare was balanced by his genius for operational organization. His offensives and counteroffensives were marked by meticulous work from his hand-picked staff. Careful placement of artillery, armor, and infantry at the precise point of an intended breakthrough was his hallmark. His method of fighting also showed careful consideration: Let the enemy overextend himself while fighting bloody engagements at every turn. When the enemy’s offensive momentum faltered, strike him at his weakest points and annihilate him.

The Soviets Hatch the Plan for Operation Uranus

The battle for Stalingrad and the Caucasus raged throughout September and October as both sides continued to pour more men into the region. Meanwhile, using the maxims that had served him so well, Zhukov and the general staff were working on a plan that would change the balance of the war in the east once and for all. The plan was known as Operation Uranus.

Looking at the extended front in the Stalingrad sector, Zhukov and his staff immediately grasped the opportunities afforded by the large areas held by the Axis allies. The Soviets had two extensive bridgeheads on the western bank of the Don facing Dumitrescu’s forces, which would provide them with their northern strike points. Constantinescu’s army, with its long, thinly held defensive front, would provide the perfect spot for the southern strike.

The Russians were already masters of deception and camouflage, but Zhukov and his staff turned it into an art. As the plans for Uranus got under way, the Soviets launched several small attacks against Heeresgruppe Mitte. Dummy formations with their own radio nets were set up in the sector, giving German intelligence officers the impression that the Russians were concentrating forces for a late fall or early winter offensive against the Heeresgruppe.

Generaloberst Reinhard Gehlen, the head of the German high command’s Fremde Heeres Ost (Foreign Armies East), was in charge of gathering and deciphering intelligence information on the Eastern Front. Although surprised at the number of Russian divisions identified during the first few months of the 1941 invasion, his office still did not appreciate the vast manpower reserves possessed by the Soviet Union.

With the purported buildup of Soviet forces in Heeresgruppe Mitte’s sector, Fremde Heeres Ost was convinced that the Russians could not possibly possess enough men to launch any sort of major offensive in the south. When nervous Romanian commanders brought up the subject of a possible Soviet offensive, they were told not to worry because the Russians were already stretched to the limit.

The Challenge of Keeping Operation Uranus Secret

Zhukov faced a daunting security problem. Massing the divisions for his offensive without being discovered by the Germans meant that the units could only be moved at night or in bad weather as they neared the front. During the day, the trains and convoys transporting men and materiel for Uranus would stop, and troops would camouflage the vehicles, making them invisible from the air.

In all, Zhukov would have 11 armies to mount his offensive. They would be augmented by several separate mechanized, cavalry, and tank brigades and corps. About 13,500 artillery pieces and mortars were assembled along with 115 rocket artillery detachments, 900 tanks, and more than 1,000 aircraft. It was a tremendous logistics operation, but the Russians were able to pull it off without the Germans being any the wiser.

Although stationed in Moscow, the Soviet marshal made extensive visits to the front to confer with his commanders about Uranus. Although they were not privy to the overall scope of the operation, the Front and Army commanders made suggestions about objectives in their particular sectors and coordination with neighboring units and gave other opinions that the marshal sent back to his Moscow staff.

The supreme headquarters and Zhukov’s staff incorporated many of the suggestions into the final plan for Uranus. Intelligence concerning opposing enemy units was also funneled directly to Moscow. As German and Russian soldiers fought and died in the rubble of Stalingrad, the buildup continued. By mid-October, the final plans for Uranus were being fine-tuned, and it was hoped that the operation could begin sometime in the first week of November.

As November approached, German commanders in the 6th Army were facing shortages in both men and materiel. They were also becoming increasingly nervous about unconfirmed reports that the Soviets were massing on their flanks. Zhukov’s deception had worked for the most part, but even the Russians could not totally mask the movements of such a massive force as it came within earshot of the Germans. Motors rumbled and horses neighed, and the sounds carried well in the crisp late fall air.

Strecker Worries About the Romanians on his Left

On Paulus’s left flank, General Karl Strecker’s XI Army Corps had three divisions to cover a front of more than 60 miles along the Don bend. Strecker knew that this was too much for his divisions to defend, so he pulled them back to well-prepared secondary positions, cutting his frontage by half.

Lieutenant General P.I. Batov immediately took advantage of the situation by sending units of his 65th Army across the Don to establish yet another Soviet bridgehead. Batov then conducted several spirited attacks against Strecker’s new positions, but the Germans were too firmly entrenched to make any progress.

While pleased with his own divisions’ performance, Strecker kept a wary eye on the Romanians to his left. The 3rd Romanian Army was woefully short of everything, especially antitank weapons. Their own were obsolete, and Dumitrescu continually badgered the Germans for more effective pieces. Some 75mm guns had been transferred to his army, but not nearly enough to stop any major Russian attack.

Berlin had also ordered General Ferdinand Heim’s XLVIII Panzer Corps to disengage from its sector on the front and form a ready reserve behind Dumitrescu’s army. Elements of the 14th Panzer Division and the 1st Romanian Tank Division were also ordered to the area. It seemed a good plan, but the nucleus of Heim’s corps, the 22nd Panzer Division, was equipped mostly with outdated Czech tanks. Also, one of its panzergrenadier regiments had been detached from the division and moved to another sector of the front.

Delays Plague the Launch of Operation Uranus

Zhukov planned to begin Uranus on November 9, but the date had to be postponed after the marshal made another series of visits to his commanders. Arriving in Serafimovich, a small Cossack farming and fishing village on the middle Don, he conferred with Generals Konstantin K. Rokossovsky and Nicholai F. Vatutin, the commanders of the Don and South West fronts. They pointed out that the freezing rain and hard frosts of the previous week had made things very difficult for the forces trying to reach the front. They also said that shortages in winter clothing had to be addressed before they felt their men were ready for battle.

Moving on to the headquarters of General Fedor I. Tolbukhin’s 57th Army south of Stalingrad, Zhukov was told that men and equipment were not arriving on schedule and that the artillery had yet to be entrenched and targeted. He returned to Moscow and postponed Uranus until November 17. Upon hearing that air units marked for the offensive might not be ready on that date, Zhukov postponed the operation for two more days.

Stalingrad was on the verge of collapse as Uranus was postponed not once, but twice. The more time that elapsed, the more chance that the Germans would find out about the massive buildup. Luckily, Berlin had other problems to deal with. On November 8, the Allies landed in French North Africa, threatening Field Marshal Erwin Rommel’s rear and dooming the vaunted Afrika Korps and Panzer Army Afrika. The German high command now had to split its attention, focusing on potential disasters on two fronts.

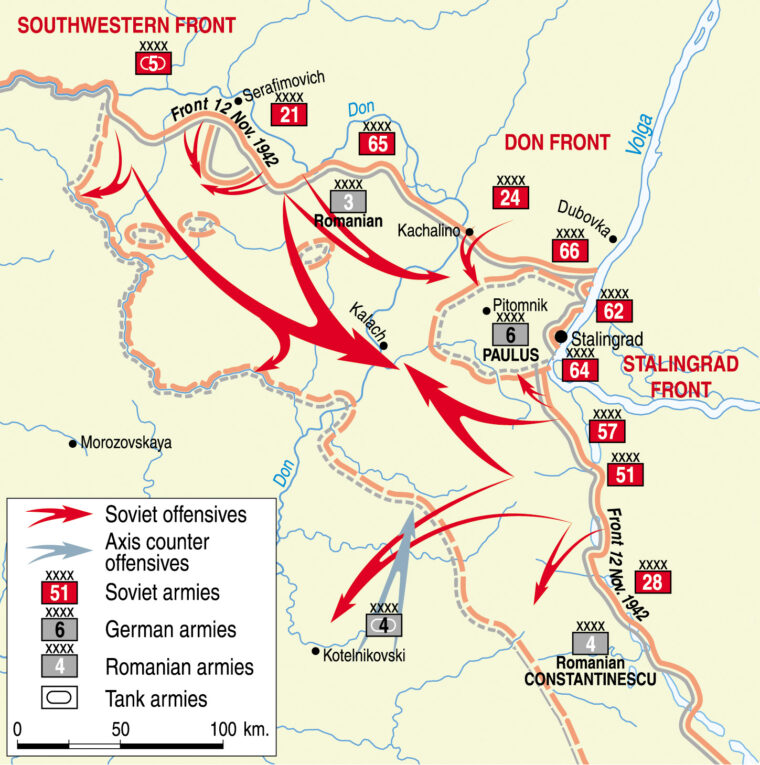

As the 19th approached, Zhukov sent out his final orders. Uranus would involve a double envelopment of Stalingrad with a primarily infantry force encircling the city itself. An outer ring, consisting of tank, mechanized, cavalry, and infantry units, would form a steel buffer against any possible German counterattack. German and allied units caught between the two rings were to be systematically destroyed and, if the opportunity arose, Soviet forces in the south would advance to Rostov and trap the divisions of Heeresgruppe A, which was still engaged in the Caucasus.

The first phase of the operation involved Vatutin’s South West Front attacking the 3rd Romanian Army out of the bridgehead on the west bank of the Don. At the same time, Rokossovsky’s Don Front would begin the envelopment of Stalingrad from the north and east. A day later, General Andrei I. Eremenko’s Stalingrad Front would attack the 4th Romanian Army in the Lake Sarpa area south of Stalingrad.

Both fronts were to send armored and mechanized forces to link up near Kalach. At the same time, other units of the fronts would spread out and head west to protect flanks as the outer ring formed.

The senior Soviet officers got very little sleep during the night of November 18. Shortly after midnight, the Russian artillery started firing smoke shells from the eastern bank of the Don. Soviet propaganda units had already set up loudspeakers close to the front weeks before, so the Germans and their allies paid little attention to the political messages and music that blasted through the night air. As usual, Axis soldiers regarded the loudspeakers as more of a nuisance designed to keep them from getting a good night’s sleep.

This time, however, the smoke and noise from the Russian line had a different purpose. Under cover of these distractions, Soviet armored and mechanized forces streamed across the Don to the already established bridgeheads. A little after 2am, more than a million men from the three attack fronts received their orders. They were told that they were about to participate in a deep raid toward the enemy rear. The word “encirclement” was not mentioned to the troops in case something went wrong with the plan. Nevertheless, the old timers knew that something was up. There were too many men and too many vehicles for this to be just a raid. Are we, they wondered, finally starting to see the beginning of the road to victory?

The Russians were helped by snow and a thick fog that cut visibility down to almost nothing. On the German-Romanian line, sentries strained to see just a few feet ahead of them, but all seemed fine except for the damned Soviet loudspeakers blaring in the distance. Only a few yards away, Red Army engineers, camouflaged in white uniforms, had been working their way toward the enemy lines all night, clearing mines and cutting wire obstacles to make a path for the Russian assault forces.

On the Soviet side, commanders anxiously looked at their watches. The fog offered good concealment and would not hinder the effects of the planned Russian artillery bombardment, as the guns had been pre-sighted for just such a situation. Minutes ticked away until, at 7:20am Moscow time (5:20am German time) the Soviet artillery commanders received the codeword “Siren.”

A Devastating Attack is Unleashed

The earth trembled as battery after battery of Katyushas (Stalin Organs) sent their rockets screaming toward the enemy lines. A ghostly glow reflected off the fog as the batteries fired again and again. To be on the receiving end of the rockets tested the courage of the best German units. For the Romanians of Dumitrescu’s 3rd Army, the effect was devastating.

Strongpoints and trenches literally disintegrated as the rockets struck their preplotted sites. Communications between the forward outposts and higher headquarters were shattered, and many of the ammunition dumps close to the front were destroyed in spectacular explosions. Many of those not killed outright in the bombardment were already fleeing to the rear, trying to escape the carnage.

Ten minutes later, the massed Russian artillery was given the order to fire. Thousands of guns roared at once, causing many an artilleryman to bleed at the ear from the concussions caused by so many artillery pieces firing at the same time. Almost immediately, shells began crashing into Romanian artillery emplacements and secondary positions behind the front line. Those fleeing from the opening bombardment were now caught in a second rain of steel, which further decimated the retreating troops. Black earth churned up from shell impacts was interspersed on the snow with red blotches that had a few seconds earlier been men fleeing for their lives.

The bombardment kept up for one hour and 20 minutes. Dazed Romanians lucky enough to escape death from the rain of explosives were in a state of near paralysis as they desperately tried to dig their way out of their shattered positions. Wounded men howled in agony for their comrades to help them while the surviving NCOs and officers worked to regain control over their troops.

Above the cries of the wounded, a new sound was heard. It was not the sound of artillery or tank motors, but the deep, guttural sound of a beast preparing to pounce on its prey. The Romanians strained to see through the fog, hoping not to see what they knew was coming. As the fog lessened, shapes appeared—first hundreds and then thousands. Coming toward them were the massed echelons of Romanenko’s 14th and 47th Guards and 119th Rifle Divisions. The sound that the Romanians now heard—the one that struck fear into their very souls—was the Russian battle cry coming from thousands of soldiers: “Urra! Urra! Urra!”

In some sectors of the Romanian front, soldiers made split-second decisions on whether they would live or die. Hundreds of them threw down their weapons and, with hands held high, hoped for the best as the Russians bore down on them. For the most part, the Soviet assault forces bypassed them and continued their advance, leaving the surrendering Romanians to be picked up later by units in the second or third wave of the attack.

In other Romanian sectors the story was different. The 13th Romanian Infantry Division, for example, occupied a sector of the front opposite the 21st Army. When the Soviet infantry attacked, survivors in the front trenches repulsed them. A second attack, this time supported by tanks, met the same fate. Frustrated, Christyakov ordered another round of shelling. At the same time, he ordered A.G. Kravchenko’s 4th Tank Corps and P.A. Pliev’s 3rd Guards Cavalry Corps to prepare to attack.

Christyakov wanted to hold these units in reserve until the Romanian line was broken, but the resistance of the 13th and some other Romanian divisions had already upset his timetable. Together with fresh waves of infantry, the Soviet assault smashed the remaining positions of the Romanian IV Army Corps, allowing the 21st Army to advance.

To the west of the IV Corps, the Romanian II Army Corps, facing the 5th Tank Army, was undergoing its own personal hell. Following the bombardment and infantry assault, Romanenko unleashed V.V. Butkov’s 1st Tank and

A.G. Rodin’s 26th Tank Corps, followed by the 8th Cavalry Corps. The attack hit the Romanian 9th, 11th, and 14th Infantry Divisions like a sledgehammer, and their positions crumbled as the Russian armor rolled forward.

The Soviet cavalry spread out toward the west, severing communications between the Romanians and General Giovanni Messe’s 8th Italian Army. As the Romanians fled, the cavalry formed a barrier against any possible counterattack while the armored and infantry forces swung southeast toward the Chir River and Kalach.

The gods smiled on the Soviets about mid-morning as the fog dissipated enough for the Red Air Force to enter the fray. Aircraft from K.N. Smirnov’s 2nd and S.A. Krasovsky’s 17th Air Armies swooped down upon the retreating Romanians with a vengeance. The Luftwaffe was nowhere to be seen as the Soviet pilots bombed and strafed enemy troops and positions.

On the Don Front, the going was more difficult. Batov threw his 65th Army at General Alexander Freiherr Edler von Daniels’s 376th Infantry Division, but his infantry made little progress against a determined German defense. Batov found easier going at the junction of the 376th and the 1st Romanian Cavalry Division, and the Soviets were able to advance as they pushed the Romanians aside. Von Daniels was forced to arc his left flank to prevent the Russians from breaking into his rear as a result of the Romanian cavalry’s retreat.

In Stalingrad, Paulus was informed of the Soviet attack at 9:45am, but he seemed relatively unconcerned. The German general ordered Heim’s XLVIII Panzer Corps to advance toward Kletskaya to support the Romanians and then went back to briefings concerning the fight for the city.

Heim put his units on the road and headed toward his objective, but at 11:30 new orders arrived, this time from Hitler’s headquarters. The feisty panzer general cursed roundly as he read the message ordering him to turn his forces northwest to the Bolshoy area and stop Romanenko’s armored units. Valuable time and fuel were lost as he reformed his attack force.

Paulus Reacts Slowly; Chooses Poorly

Meanwhile, Paulus began receiving more reports concerning the Russian attack. The first fragmented information had caused little alarm. After all, they were coming from Romanians, and everyone knew that they tended to exaggerate and were prone to unnecessary panic.

Toward noon, the situation became clearer. This time the staff officers of the 6th Army definitely took notice. A Luftwaffe reconnaissance aircraft reported hundreds of Soviet tanks advancing across the steppes northwest of Stalingrad. Clear reports from German liaison officers flatly stated that the 9th, 13th, and 14th Romanian Infantry Divisions had been shattered and were no longer capable of any organized resistance.

Although Paulus had three panzer divisions (14th, 16th, and 24th) and three motorized divisions (3rd, 29th, and 60th) at his disposal, he did nothing to form a strike force to stop the Soviet armor. Preferring to keep them engaged in and around Stalingrad—a pure waste of armor in an urban battle—he relied on Heim’s panzer corps to deal with the Russian attack.

A German panzer corps in 1942 was a formidable weapon that could take on a Soviet Tank Army and usually come out on top. Heim’s corps, however, was a panzer corps in name only, something that seemed to slip by the generals that were expecting him to stop the Russians.

By the time Heim was ordered to attack, his 22nd Panzer Division had only about 30 combat-ready tanks. His motorized elements were critically short of fuel, and the orders changing the direction of his attack only made the problem worse.

Heim’s mechanized units were also plagued by the forces of nature. While bivouacked, mice had gotten into the tanks and armored personnel carriers and had gnawed on or through some of the electrical wires in the vehicles, causing them to break down as the systems shorted out. Another problem was the width of his tank treads. The Russian T-34 had a wide, gripping track while German tanks had narrow tracks, causing them to slip and slide on the icy terrain. Nevertheless, Heim and his men pushed forward, hoping to surprise the Russian spearhead.

The weather worsened during the afternoon of the 19th, with the freezing mist lowering visibility to almost zero, and maps were practically useless as the Soviets continued their drive. Taking into account the possibility of bad weather, Russian commanders had enlisted area peasants as guides, but even they were having a difficult time traversing the mist-shrouded landscape.

It started getting dark before 4:00pm, which only added to the difficulties faced by the Russian tank crews as they pushed toward their objectives. To make things worse, the wind picked up and snow began falling, which led to almost blizzard-like conditions on the steppes.

Heim’s Suicidal Engagement

Having essentially obliterated the Romanian defenses, the Soviet tank commanders felt reasonably assured that their only threat would come from a possible German counterattack. All things considered, that attack would probably be directed against Kravchenko’s 4th Tank Corps, as that unit was advancing closest to the main 6th Army forces at Stalingrad.

It would have worked that way if Heim had not received new orders sending him toward Bolshoy. Heim’s panzers, now numbering about 20, hit Butkov’s 1st Tank Corps near the Chir River at Pestchany. It was an uneven battle from the start, with the Germans being outnumbered, outgunned, and outmaneuvered. In an almost suicidal action, an armored group led by Oberst (Colonel) Hermann von Oppeln-Bronikowski tore into the Russians. Supported by the 22nd Panzer’s antitank battalion, von Oppeln’s tanks managed to isolate and destroy several Soviet tanks in Butkov’s spearhead.

The Soviets regrouped, and the unequal struggle continued into the night until Heim ordered the battle to be broken off. He told his commanders to make for the Chir River crossings and get to the west bank of the river, thus saving his panzer corps from encirclement and annihilation. Those retreating units would remain a thorn in the side of the Russians for days to come.

The retreat order had the expected consequences for Heim as a furious Hitler recalled him to Berlin, stripped him of his rank, and had him imprisoned. He was released 10 months later without having been tried. On August 1, 1944, his rank was restored, and he was appointed commander of Fortress Boulogne on the Western Front.

At Heeresgruppe B headquarters, Generaloberst Baron von Weichs recognized the danger he faced earlier than most. He issued directives at 10:00pm on the night of November 19 to try and forestall the looming disaster.

“The situation developing on the front of the 3rd Romanian Army dictates radical measures in order to disengage forces quickly to screen the flanks of 6th Army,” he wrote.

Among those measures was ordering all offensive operations in Stalingrad to cease. He also directed Paulus to detach two motorized formations, an infantry division, and all anti-tank units he could spare to stop the assault forces of Vatutin and Rokossovsky. These measures may have blunted the Soviet advance, but it was already too late. On November 20, the second stage of Uranus began as Eremenko’s southern anvil began moving to meet the northern hammer.

The same bad weather plaguing the northern Soviet forces also hampered the Russians in the south. Icy fog made the going slow as the assault forces of the Stalingrad Front edged closer to Constantinescu’s 4th Romanian Army. At 10am, the Russian artillery opened up along the front. Soon after, the initial assault troops were already pouring through the Romanian line.

German soldiers in the 297th Infantry Division, adjacent to the 20th Romanian Infantry Division, watched in awe as the human flood of Russians advanced. As on the northern sector, some of the Romanians fled or surrendered almost immediately, while others fought bravely until being overwhelmed. Reports came in speaking of Romanian antitank crews firing their pitiful 37mm guns until they were crushed beneath the marauding Soviet tanks of the initial attack forces.

The leading Russian armored and mechanized forces performed well, but command and control problems, the bad weather, and problems getting across the Volga River crossing points delayed the spearhead units designated to exploit the breakthrough. Maj. Gen. V.T. Volsky’s 4th Mechanized Corps, designated to advance with Maj. Gen. N.I. Trufanov’s 51st Army, was supposed to strike between Lakes Sarpa and Tsatsa, but its units had not yet concentrated. The same could be said for Colonel T.I. Tanaschishin’s 13th Mechanized Corps.

Angry messages flew back and forth as the delay continued. The spearhead units were supposed to attack at 10am, but it was already well after noon, and there was still no sign of movement from the corps. General Markian M. Popov, the deputy commander of the Stalingrad Front, headed to Volsky’s headquarters and confronted him directly.

The angry exchange between the two lasted for some time before Volsky finally gave in and ordered his still disorganized units forward. Tanaschishin was also ordered forward immediately. It was already past 4pm, and the Soviet timetable was hours behind schedule. As they moved out, Volsky’s units became intermixed, causing further confusion as they headed westward.

The Germans reacted much more quickly to the southern attack than they had on the previous day. General Hans-Georg Leyser’s 29th Panzergrenadier Division, nicknamed the Falcon Division, was ordered to hit the flank of Tanaschishin’s 13th Mechanized Corps. The 29th was a first-rate division, and its troops moved out quickly to meet the foe.

About 10 miles south of Beketovka, Leyser’s armored columns slammed into elements of Tanaschishin’s corps. The panzers bloodied the Russian tanks and sent the mechanized units reeling, causing the Soviets to beat a hasty retreat. It was a shining moment in an otherwise dismal day for the Germans, but the victory was short lived.

Farther west, the Soviets were running rampant through the retreating Romanians. Leyser was ordered to turn his division around to protect the exposed southern flank of the 6th Army, leaving the field to Tanaschishin’s forces, which were regrouping for a counterattack.

While the fighting raged south of Stalingrad, the northern sector reeled under hammer blows from the South West and Don Fronts. General Strecker’s IX Army Corps, its left flank left hanging by Dumitrescu’s retreat, was forced to form an arc to meet the advancing Russians. General von Daniels’s 376th shifted its front westward to meet the 3rd Guards Cavalry Corps, while General Heinrich-Anton Deboi’s 44th Infantry Division, forced to leave much of its heavy equipment in place because of lack of fuel, extended its line to cover the gap left by von Daniels’s shift.

Meanwhile, Kravchenko’s 4th Tank Corps turned toward the southeast. Its objective was the Don River town of Golubinski, which happened to be Paulus’s headquarters. At the same time, units of the 5th Tank Army continued to smash isolated pockets of Romanians that tried to stand and fight.

The Jaws of the Trap Close in on the Germans

The Russian infantry was now moving steadily forward, leaving the armored and mechanized units to continue to work on closing the jaws of the trap. Rodin’s 26th Tank Corps took Perelazonvsky, about 80 miles northwest of Stalingrad. Butkov’s 1st Tank Corps snapped at the heels of Heim’s XLVIII Panzer Corps, which was starting to retreat to the southwest, while the 8th Guards Cavalry Corps continued its drive to the Chir River. Despite several difficulties, the 20th had been an excellent day for Uranus.

On Saturday, November 21, the 21st Army spearhead continued moving southeast, closing on Golubinski. Paulus, finally realizing the disaster overtaking him, asked Berlin for permission to pull his army out of Stalingrad and for a new defensive line on the Don. He then relocated his headquarters to Nizhnye Chriskaya, a village about 40 miles to the southwest.

Later that day, Paulus received two messages from Hitler. The first one read: “The commander-in-chief will proceed with his staff to Stalingrad. The 6th Army will form an all-round defensive position and await further orders.”

Later in the day, Hitler sent Paulus the following message: “Those units of the 6th Army that remain between the Don and the Volga will henceforth be designated Fortress Stalingrad.”

The two messages not only sealed the fate of the 6th Army, but they also meant that Zhukov would not have to worry about any kind of breakout attempt by the Stalingrad forces. In effect, it gave him the opportunity to start solidifying his inner ring around the city while concentrating on closing the outer ring.

Between the inner and outer rings, Germans and Romanians were still fighting. Heim’s XLVIII Panzer Corps, trying to make its way to the Chir River crossings, actively engaged Soviet forces in several pitched battles as they made their bid for freedom. General Mikhail Lascar had gathered remnants of the V Romanian Army Corps farther north and was resisting repeated Russian attempts to overrun his hastily constructed defenses. Hoping for German support, Lascar would wait in vain for any relief effort.

While these clashes were taking place in the north, Eremenko’s southern offensive was running into problems, despite having effectively split Hoth’s 4th Panzer Army in half. Most of Hoth’s German units were trapped inside the ever tightening ring around Stalingrad. The 4th Romanian Army, which had been subordinated to Hoth’s Panzer Army, was in disarray, and the 16th Panzergrenadier Division, the only German unit outside the Stalingrad sector, was making a fighting withdrawal through heavy opposition.

It was a golden opportunity for the Russians, but command failure was still a problem that plagued even the highest ranks of the Red Army. Tolbukhin’s 57th Army and Shumilov’s 64th Army were making good progress closing the inner ring around Stalingrad. Trufanov’s 51st Army was a different matter.

Once the breakthrough was achieved, Trufanov was supposed to send his 4th Mechanized Corps and 4th Cavalry Corps speeding northwest to Kalach while the bulk of his infantry was to head southwest as a shield for his left flank. The coordination and complexity of controlling both armored and infantry forces moving in different directions proved too much for Trufanov and his staff.

Instead of the quick thrust toward Kalach, the mechanized and cavalry forces moved sluggishly to the northeast, giving many of the retreating Romanians a chance to flee for their lives. The flanking infantry advanced even more slowly, amazing even Hoth as he followed their progress. Although his remaining forces could have been destroyed by a more aggressive Soviet posture, all he faced on the battlefield before him was “a fantastic picture of fleeing (Romanian) remnants.”

Sunday, November 23, found the Russians in the north advancing on the Don in force. In the predawn hours, an assault unit captured a newly constructed bridge across the river at Berezovski near the primary objective of Kalach. It was the first Soviet victory of the day, but it would not be the last.

By now, communications between the 6th Army headquarters and outlying units had almost completely broken down. At Kalach itself, word of the Soviet breakthrough only reached the garrison on the morning of the 21st. The troops occupying the town, which was located on the eastern bank of the Don, consisted mostly of maintenance and supply personnel and included the workshops and transport company of the 16th Panzer Division. They were augmented by a Luftwaffe flak battery and a small force of field police.

There had been no other word about the breakthrough since a message concerning the breakthrough in the south was received on the afternoon of the 21st. Tasked with defending both Kalach and the western bank, the garrison faced an impossible situation. The town commander had no idea that three Soviet corps were heading directly for him, and even if the Germans had known, the garrison had no way to stop them.

With the Berezovski Bridge in Russian hands, Maj. Gen. Rodin sent Lt. Col. G.N. Filippov and his 19th Tank Brigade speeding along the Don to Kalach. Using captured German vehicles to lead the way, Filippov’s men overwhelmed the detachment guarding the Don bridge. On the western heights, Luftwaffe 88mm field guns opened fire and destroyed several Russian T-34 tanks.

Filippov, not waiting for his mechanized infantry, ordered a detachment of tanks to cross the river and form a bridgehead on the eastern banks while other T-34s continued to duel with the 88s. When the infantry did appear, he once again split his forces, sending some infantry across the river and ordering the rest to support the tanks trying to take the heights. A combined assault finally silenced the German guns, and the heights were taken by midmorning.

The Soviet Spearheads Meet at the Karpovka

From their new vantage point, the Russian tanks on the western bank poured round after round into Kalach, while their comrades on the eastern bank stormed the town’s flimsy defenses. Those Germans that could escape loaded themselves on anything drivable and fled toward Stalingrad. By early afternoon, Kalach was in Russian hands.

In the south, Trufanov was finally getting his forces under control. Although his infantry was still slowly plodding westward and southwestward, his mechanized units were advancing at a faster pace. By the end of the day, Volsky’s 4th Mechanized Corps had taken Buzinovka and was moving toward Sovietski, a few miles east of Kalach near the junction of the Don and Karpovka Rivers.

In essence, by the end of the day any German or Romanian units east of the mechanized ring had only one place to go—Stalingrad. General Lascar, surrounded and running low on ammunition, refused several Russian requests to surrender. His force was overwhelmed, its survivors forming long gray columns marching east toward a very uncertain future.

By now, there was little to stop the northern and southern spearheads from completing their missions. Volsky reached the south bank of the Karpovka a little after noon on November 23. The 45th Tank Brigade of Kravchenko’s 4th Tank Corps arrived on the opposite bank around 4pm. Zhukov’s trap was finally closed, with about 300,000 of the enemy in the giant cage called Stalingrad.

The meeting of the northern and southern pincers was later restaged for Soviet propaganda films, but there is little doubt that the emotions shown on the screen were the same felt by Volsky’s and Kravchenko’s troops as they first joined. Although Heeresgruppe A was able to make a masterful withdrawal from the Caucasus in the months to follow, the Red Army had bottled up the 6th Army and a good deal of the 4th Panzer Army. It was a great victory.

Operation Uranus was only the first step in the annihilation of Fortress Stalingrad, but it was a giant one. Despite control problems, Zhukov and his commanders in the field had shown that they had learned the lessons vital to modern mechanized warfare. Methods developed during Uranus were finely honed and used again by Zhukov and others in later operations that would shake the foundation of the German military and finally bring it crashing down.

Pat McTaggart is an expert on World War II on the Eastern Front. He is also the author of the book Siege! about six epic sieges during the war in that theater. He resides in Elkader, Iowa.

Join The Conversation

Comments