By John Walker

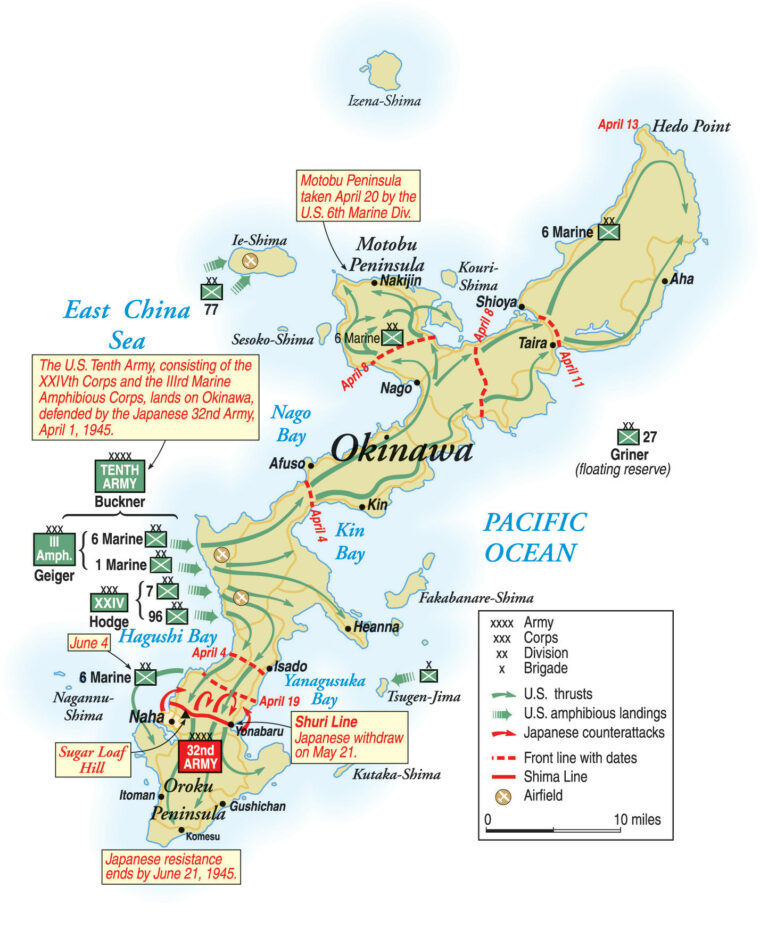

On Easter morning, April 1, 1945, the Pacific island of Okinawa trembled beneath an earthshaking bombardment from American combat aircraft overhead and ships steaming offshore in preparation for an amphibious landing of unprecedented magnitude. The commander of Japan’s massive 32nd Imperial Army, Lt. Gen. Mitsuru Ushijima, stood quietly on the crest of Mount Shuri near the southern end of the island, calmly watching the spectacle. He and his chief of staff, Maj. Gen. Isamu Cho, and his senior operations officer, Colonel Hiromichi Yahara, watched through binoculars as the American landing force—four infantry divisions commanded by U.S. Army Lt. Gen. Simon Bolivar Buckner—disembarked from some 1,000-odd landing craft and pushed ashore unchallenged.

For almost a year Ushijima’s army, more than 100,000 strong, had been busy constructing an intricate system of hidden bunkers and fortified ridges in Okinawa’s hilly southern region. Thousands of island residents had been impressed to help build the Japanese defenses. Ushijima had stationed the bulk of his strength in the south and planned to lure the American invasion forces into a catastrophic battle of attrition after allowing them to land on the island unmolested. The Japanese strategy was to drive off the American fleet with conventional attacks and suicidal kamikaze attacks and then annihilate the stranded invasion force. So many American soldiers, sailors, and Marines would perish, Ushijima reasoned, that the Americans would shrink back with horror at the mere thought of invading the Japanese mainland, some 350 nautical miles away.

As American tank and infantry units moved toward the southern end of the island, they would confront an intricate system of two concentric defensive lines constructed along a series of hills, ridges, and draws—the Machinato Line—and behind it the even more heavily fortified Shuri Line. The defenses were manned by veteran, well-armed Japanese soldiers who would remain loyal to their Bushido code of warfare and fight to the death rather than be captured. Yahara, a gifted strategist who helped design and implement the Japanese strategy, was short on tanks but had stockpiled hundreds of heavy weapons and artillery pieces of every caliber—150mm howitzers, 120mm mortars, 47mm antitank guns, and the dreaded 320mm “spigot” mortars—in hidden caves and concrete bunkers that were virtually impervious to air and artillery fire. Yahara’s concept of a yard-by-yard war of attrition, or jikyusen, was a radical departure from previous Japanese island defenses, all unsuccessful, which had concentrated on annihilating the enemy at the water’s edge with massive banzai charges and frontal assaults.

Okinawa: A Strategic Island

The American military wanted Okinawa for three reasons: its seizure would sever the remaining southwest supply line to resource-starved Japan; American medium-range bombers could reach the Japanese mainland from the four airfields on the island; and Okinawa’s harbors, anchorages, and airfields could serve as a final staging area for the planned late-1945 invasion of the Japanese mainland itself. A huge assemblage of forces from Admiral Chester Nimitz’s Central Pacific island-hopping campaign and General Douglas MacArthur’s Southwest Pacific advance converged on Okinawa. In all, Buckner commanded more than 180,000 troops from four Army divisions (the 7th, 27th, 77th, and 96th) under Maj. Gen. John Hodge, and three Marine divisions (the 1st, 2nd, and 6th) under Maj. Gen. Roy Geiger. It was many more troops than Buckner’s namesake father had commanded—and surrendered to Ulysses S. Grant—at Fort Donelson, Tennessee, during the American Civil War.

The Japanese invasion of China in the 1930s initially had little impact on the inhabitants of the Ryukyu Island chain, which runs southwest from the Japanese home island of Kyushu toward Taiwan. Despite its size—it was the largest of the Ryukyu Islands—and its dense native population, Okinawa had neither surplus food nor significant industry to assist the Japanese war effort. The island’s main wartime contribution was the production of sugar cane, which was converted into commercial alcohol for torpedoes and engines. From the first days of the Pacific War, Okinawa was fortified as the front line of defense for mainland Japan. Land and farms were forcibly expropriated throughout the island, and Japan’s Imperial Army began the construction of numerous air bases. Almost half a million Okinawans were intermingled with the Japanese garrison as active, if unwilling, participants in the island’s defense. To keep them loyal, Ushijima had propagandized the populace by telling them that capture by American forces would result in torture, rape, and death, to which suicide was infinitely preferable.

By autumn 1944, Okinawa had been targeted for invasion by Allied forces. The largest amphibious assault of the Pacific War, dubbed Operation Iceberg, would involve assembling one of the greatest naval armadas in history. Admiral Raymond Spruance’s Fifth Fleet included more than 40 aircraft carriers, 18 battleships, 200 destroyers, and hundreds of assorted support ships. The initial assault on the 60-mile-long island was planned for April 1, 1945. On September 29, 1944, B-29 bombers conducted the initial reconnaissance mission over Okinawa and its outlying islands. On October 10, the day after the fearsome and fanatical General Cho boasted to a group of Okinawans in the capital city of Naha that the Japanese defenders would win a decisive victory, nearly 200 of Admiral William “Bull” Halsey’s planes struck Naha in five separate waves and almost devastated the city. Meanwhile, the U.S. Air Force, under the leadership of General Curtis LeMay and operating from bases in the Mariana Islands, began a strategic bombing campaign using B-29s against the mainland of Japan, a campaign that culminated in horrific incendiary raids in March 1945.

Less heralded, but arguably more effective in undermining Tokyo’s military strategy, was the extraordinary success of the American submarine fleet. In 1944 alone, approximately a half million tons of Japanese shipping was sunk by American subs. By early 1945 it was too hazardous for Japanese troop ships to attempt to travel outside the main islands.

The Defender’s Advantage

In mid-March 1945, a combined British-American fleet of more than 1,300 ships gathered off Okinawa to prepare for the naval bombardment; the first kamikaze attacks of the campaign began on March 18. Named for the “divine wind”—typhoons that in 1274 and 1281 had blown away Kublai Khan’s Mongol armadas and saved Japan from invasion—the Kamikaze Special Attack Corps was an example of the desperation infecting Japan’s Imperial Headquarters in Tokyo by early 1944. From the moment Japan entered World War II, it began losing pilots far more rapidly than they could be replaced. By 1944, new Japanese pilots, who were being sent into combat with less than one-third the flight training time that American pilots received, were being shot down in disproportionate numbers. The antiaircraft capabilities of U.S. Navy ships had also increased to such an extent that attacking an American vessel had essentially become a suicide mission anyway. The Japanese decided that it would be more practical for their pilots to deliberately plunge their aircraft into the enemy’s warships, ensuring the ship’s destruction as well as their pilots’. The operational creed became “one plane, one ship.” Some 4,000 Japanese planes were stockpiled for the kamikaze attacks.

American troops secured two positions prior to landing day. The small island groups of Kerama and Keise, southwest of Okinawa, could be used to provide anchorages for ships and as an artillery base to back up ground forces once they went ashore. Against occasionally stiff resistance from isolated garrisons, American forces secured Kerama on March 28 and Keise on March 31. At Kerama, they also destroyed 350 suicide boats, speedy craft loaded with depth charges that the Japanese had planned to use against the Allied fleet. U.S. planners anticipated a bloodbath when the main landing took place since it would be the first time that American and Japanese forces would clash on Japanese soil. American intelligence, unfortunately, grossly underestimated the size of the garrison on Okinawa, placing the number at no more than 65,000 troops. In fact, Okinawa harbored some 110,000 crack Japanese soldiers, at least five times the number that had badly bloodied U.S. forces at Iwo Jima. In addition, some 20,000 Okinawans had been drafted into home defense units, or boeitai, to serve as auxiliary forces.

The American planners, who saw the Okinawa campaign as an exercise in overwhelming material and numerical advantages, were unaware that many advantages remained with the Japanese defenders. In the war of attrition to come, the Japanese had packed more than 100,000 troops into the southern third of the island where they, not the Americans, possessed the high ground and the greater concentration of force. The island itself was larger than many of the other Pacific atolls stormed in earlier campaigns, and its unpredictable weather, razor-sharp coral rocks, and dense vegetation gave defenders even more advantages than they had enjoyed at Iwo Jima, where a garrison of 23,000 Japanese troops had claimed the lives of 6,000 Marines.

The Machinato Line

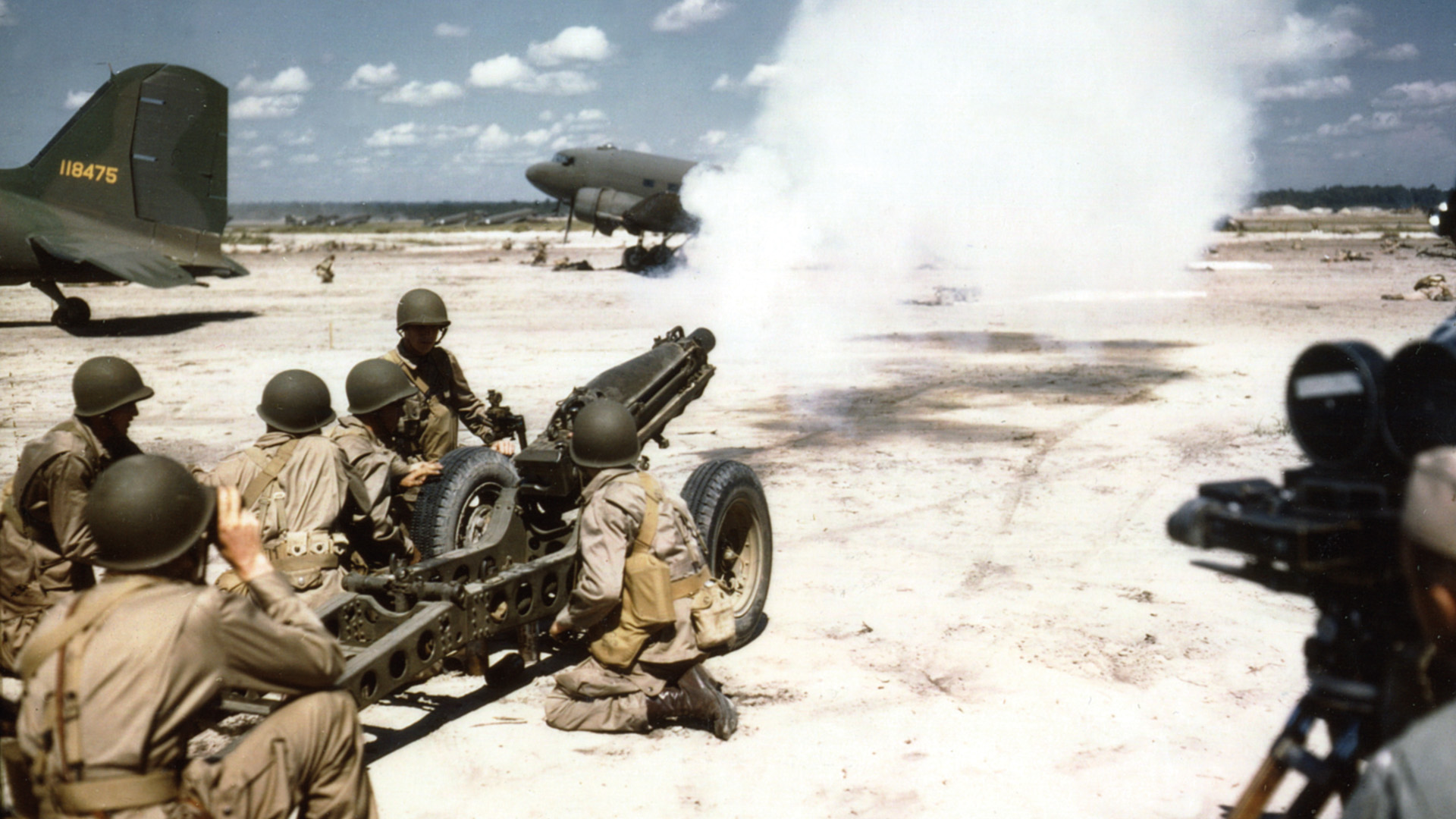

The people of Okinawa had long been resigned to the severe typhoons that periodically swept their island, but nothing in their experience equaled the tetsu no bow—storm of steel—that pounded the island on April 1 preceding the American landing. Indeed, it was the heaviest concentration of naval gunfire ever to support an amphibious landing. While the 2nd Marine Division conducted a demonstration landing on Okinawa’s southeast beaches, the 7th and 96th Infantry Divisions of the Army’s XXIV Corps and the 1st and 6th Marine Divisions of the III Marine Amphibious Corps crossed the Hagushi beaches. Some 16,000 troops landed in the first hour, and by nightfall more than 60,000 American troops were safely ashore, with another 120,000 waiting in ships offshore. Marine and Army units advanced rapidly inland toward the vital airfields of Kadena and Yontan. Within three hours, troops of the 6th Marine Division had seized Yontan, while soldiers of the 7th Infantry Division advanced to secure Kadena and continued inland. By day’s end, the Americans had secured a beachhead nine miles wide and three miles deep, at a remarkably small cost of 28 men killed or missing and 104 wounded.

American forces moved rapidly eastward to cut the island in two in just four days, capturing as much territory as planners had expected to take in three weeks. Marines of the 6th Division wheeled and turned north, moving up the island until they reached the Motubu Peninsula, where the Japanese had entrenched around the rugged hills of Yaeju-Dake. More Japanese were waiting on the island of Ie Shima as well. As the Marines closed in on Yaeju-Dake, troops of the Army’s 77th Infantry Division invaded Ie Shima. After 12 days of heavy fighting against 2,000 dug-in defenders, Motubu was secured by the Marines on April 20 at a cost of 213 killed or missing and 757 wounded. The GIs who attacked Ie Shima encountered heavy resistance as well, but they were also able to achieve their objective. Some 4,700 Japanese soldiers died on Ie Shima, while the men of the 77th lost 172 killed, 902 wounded, and 46 missing. Ie Shima was quickly turned into an ideal base for American fighter aircraft. (The celebrated American war correspondent Ernie Pyle was killed by Japanese machine-gun fire on Ie Shima on April 18.)

While the fighting heated up in the north, Army units began advancing southward on April 9 and immediately hit stiff resistance when they struck Ushijima’s first line of defense, the Machinato Line. Anchored on the Machinato Inlet, it included a series of fortified ridges, draws, cliffs, and caves, most notably Kakazu Ridge, where coral hills were pitted with caves and passageways filled with enemy soldiers that blocked movement along Okinawa’s west coast and stretched from one end of the island to the other. After failed assaults on the southwestern part of the island between April 9 and 12, American GIs suffered nearly 3,000 casualties, killing more than 4,000 Japanese in the process but failing to secure even a few hundred yards of coral.

For more than a month, a seemingly endless succession of heavily defended enemy positions stalled Buckner’s offensive. A typical ridge on Okinawa had enemy machine-gun positions on the forward slope and on nearby hills that intersected each trail, while mortar crews were dug into invisible positions on the reverse slope to rain shells down on the advancing Americans. Japanese artillery, located farther back at higher elevations, incessantly fired shells of every caliber night and day, inflicting staggering casualties and sending droves of shell-shocked GIs to aid stations in the rear. Each night, squads of Japanese suicide troops ventured out and infiltrated American positions, throwing grenades and wreaking havoc on their exhausted enemies.

Buckner committed two full-strength divisions against the Machinato Line, the 7th Infantry Division on Okinawa’s east coast and the 96th Infantry Division on the west, but neither made significant forward progress. By April 12, however, the Americans had cemented their line, their right flank along Kakazu Ridge, their center across from Tombstone Ridge, and their left abutting the town of Ouki. Kakazu Ridge was a 280-foot-high elevation that was home to 1,200 defenders. On April 9, Colonel Edwin May’s 383rd Regiment attacked the ridge in the predawn hours, hoping to catch the Japanese by surprise. With no artillery preparation, the men of the 383rd went in without tank support as well, because the approaches to Kakazu were cut by a deep gorge. May’s troops made it to the crest of the ridge against little opposition, but when dawn came a massive artillery and mortar barrage hit the attackers hard and a Japanese counterattack drove them off the narrow crest. By late afternoon May’s units had been forced to withdraw, suffering the loss of 23 killed, 47 missing, and 256 wounded. The next morning American artillery and naval guns again pounded Kakazu Ridge, and two regiments charged up the hill, only to be stopped cold by Japanese defenders who emerged unscathed from the reverse slopes.

Kamikaze Counterattacks

The Japanese launched a carefully designed counterattack on April 12. In the past, outright banzai charges had been disastrous, so the Japanese turned to stealth instead. During the night, dozens of Japanese infantry squads tried to infiltrate American lines and ambush rear-echelon support elements the next morning. Only one infiltration attempt succeeded, however; the rest met heavy resistance and were shredded by alert defenders. A Japanese survivor later wrote, “Continuous mortar and machine gun fire lasted until dawn, when we, having suffered heavy casualties, withdrew. The company fell apart during the withdrawal.” An American report stated that the Japanese dead were “stacked like cordwood.”

On the U.S. left, XXIV Corps troops managed to advance into the town of Ouki, but they were repulsed and withdrew after hours of fierce fighting. In the center, American forces fought their way up aptly named Tombstone Ridge, but were also thrown back by the Japanese defenders, some using flamethrowers. All along the Machinato Line, Ushijima’s troops stopped virtually every attempt by the 96th and 7th Divisions to advance during the second week of April. The defenders paid a staggering cost for their initial successes, however. American casualties were estimated at 2,900 (451 killed, 2,198 wounded, and 241 missing), while Japanese losses were believed to number at least 5,750. Some Japanese officers, claiming they had no reinforcements to replenish their units after suffering such heavy losses, called for an all-out offensive to blunt the American onslaught.

On April 14, Buckner came ashore and informed his commanders that he wanted the American line to advance immediately from coast to coast. To get things moving, he advanced the 27th Infantry Division and deployed it in the western sector opposite Ushijima’s left, moved the 96th to the center, and kept the 7th along the east coast. After some 19,000 shells pounded the Machinato Line, all three divisions moved out on April 19, but by day’s end the American forces had made almost no progress. A tank advance by the newly arrived 27th ended with 22 of 30 tanks lost to antitank weapons and suicidal Japanese soldiers carrying satchel charges. Finally, some progress was achieved on April 20, when troops from the 27th Division breached the Machinato Line and moved five miles south before digging in.

Meanwhile, the U.S. fleet had begun suffering under the first successive waves of kamikaze attacks. On April 6-7, Imperial Headquarters in Tokyo launched the long-promised air and sea attacks on the Allied fleet off Okinawa. All day on April 6, some 223 Japanese planes attacked the American armada offshore and various radar-picket destroyers northeast of Okinawa. Despite inexperienced pilots and inadequate air cover from Zero fighters, the unprecedented number of aircraft engaged allowed the Japanese to hit at least 14 American ships, sinking four and damaging 10 others. During the next 10 weeks, the Americans offshore would face at least 10 organized attacks involving hundreds of planes, sometimes as many as 350 at a time.

The second portion of the Japanese counterattack involved the super battleship Yamato, whose 70,000-ton displacement and nine massive 18-inch guns made her the world’s largest and most feared battleship. Given enough fuel for a one-way trip, Yamato was directed to beach herself on the coast of Okinawa and become both an artillery platform and a target to divert American carrier aircraft from air assaults on Okinawa itself. Yamato was given no air cover, however, and on April 6 swarms of American carrier aircraft began deluging the ship with fire. One day later she sank, along with a cruiser and most of the screening destroyers.

The kamikazes returned on April 12 in ever greater numbers. Some 350 bombers and fighters sortied from Kyushu, intermingled with escort fighters and a small number of experienced pilots who would make conventional attacks. The Japanese dropped chaff (thin foil strips) to confuse radar, and attacked near dusk, coming in from all directions and altitudes. The Zeros damaged some of the largest ships in the Allied fleet—the carriers Essex and Enterprise, the battleships Missouri, New Mexico, Tennessee, and Idaho, the cruiser Oakland, and dozens of destroyers, minesweepers, and gunboats. On April 16 the kamikazes managed to hit another carrier, Intrepid, as well as more destroyers and minesweepers. On May 3 and 4, some 305 Japanese planes damaged nearly a dozen picket destroyers and support ships.

Buckner’s Stubborn War of Attrition

Concerned about the slow progress achieved thus far by American ground forces, Admiral Chester Nimitz, commander in chief of the Pacific Fleet, flew to Okinawa and conferred with Buckner. Nimitz complained that his fleet of almost 1,600 ships “was losing about a ship and a half a day” to suicide attacks, and he urged Buckner to mount an amphibious assault behind Japanese lines to break the stalemate. Buckner demurred, preferring to continue his straight-ahead attacks. Buckner would continue to pour more men into piecemeal frontal assaults, ignoring pleas from his subordinates to starve, surround, or bypass the seemingly impregnable pockets of Japanese resistance. Maj. Gen. Andrew Bruce, commander of the 77th Infantry Division, argued for a southern landing behind the Shuri lines to force the Japanese to fight in two directions, but Buckner rejected his plea.

Constant pressure by Buckner’s three Army divisions, with resulting heavy losses on both sides, finally split open the Machinato Line in late April. The so-called blowtorch and corkscrew method used by the attackers, in which gasoline was pumped into caves and ignited and cave entrances were blown up by explosives, ensured that the fighting would be vicious, close-up, and often hand-to-hand. With the exception of two heavily defended pockets near the center and the right flank where the defenders still held fast, the Japanese began withdrawing from their original line under the cover of artillery barrages. From April 25 to May 3, American units made steady advances toward the Shuri defenses. Buckner rearranged his front lines, bringing the 6th Marine Division down from the north to face Ushijima’s western flank and replacing the weary 27th Infantry Division with the 1st Marine Division. In the eastern sector the 77th Division moved up to give the weary 96th some rest, while the 7th remained on the western flank of the Army’s sector. The American front now consisted of two Marine divisions on the west and two Army divisions in the east.

Meanwhile, urged by his frontline commanders to launch an offensive, a reluctant Ushijima agreed, unleashing a surprise attack on the reorganized American lines on May 3. He sent two waves of engineers around the western and eastern flanks in amphibious assaults designed to land behind American lines and distract them while a third attack targeted the center of the American line. The operation proved disastrous from the beginning. On the western shores, the engineers landed opposite the Marine line rather than behind it, and Marine mortars and machine guns quickly annihilated the attackers. On the eastern shore, American naval vessels alertly spotted the assault barges and opened fire, destroying most of the Japanese landing craft and killing most of the engineers. The Japanese infantry attack, set to jump off at dawn, was delayed, and the 2,000-man force was shredded by heavy and accurate American artillery fire. The ill-advised offensive cost the Japanese almost 7,000 of their most seasoned frontline troops, 19 artillery pieces, and much valuable real estate. When the attackers faltered, troops from the 1st Marine Division advanced several hundred yards across no-man’s-land. Operations Officer Yahara later wrote, “This disaster was the decisive action of the campaign.”

The bloodbath was far from over, however. It would drag on for another seven bloody weeks, in part because Buckner’s frontal-assault tactics played directly into the hands of Ushijima’s strategy of attrition. After the failed offensive, Ushijima continued withdrawing his troops to the Shuri Line, an eight-mile path stretching from Yonabaru on the east coast through tortuous ridges near Shuri castle, and into the port city of Naha on Okinawa’s western coast. On May 11, Buckner began an offensive against the Shuri Line with his rearranged forces. Once again, Army units in the east encountered fierce resistance all along the line. Closest to the coast, XXIV Corps units bogged down for two days at a key height called Conical Hill before gaining a foothold on the crest and withstanding vicious Japanese counterattacks for another three days. Farther west, the 77th Division battled through its own hell, especially at Ishimmi Ridge, a 350-foot rise a third of a mile from Shuri.

Bloody Battle for Sugar Loaf Hill

The two Marine divisions fighting along the western half of Buckner’s line faced a particularly daunting task in their efforts to eliminate the stronghold at Shuri. Four locations in particular tested the Marines’ tenacity—Dakeshi Ridge, Wana Ridge, Wana Draw, and, above all, Sugar Loaf Hill. The 1st Marine Division advanced toward Dakeshi Ridge on May 11, but gained little ground against an enemy dug in on both slopes. Under horrific fire, the Marines resorted to doing much of their fighting in squad-sized units. A solitary Marine would edge cautiously forward toward an enemy machine-gun position or cave, while his buddies laid down a heavy covering fire, and then he would toss in a satchel charge or grenade. Anyone staggering out of the cave would be cut down by rifle fire or flamethrower. After three days of heavy fighting, Dakeshi Ridge fell. Wana Ridge and Wana Draw took longer; Marines moved against Wana Draw on May 14, but could not advance against heavy fire from hundreds of hidden enemy positions. The constant shelling from both sides, together with torrential rains that began on May 21, turned Wana Ridge and Wana Draw into muddy quagmires. Corpses of slain Marines had to be left where they were because retrieving them exposed more men to the heavy artillery placed on Shuri Heights. The remains of dead Americans and Japanese slowly rotted or were blown to bits by shells that fell around the clock. It seemed to American commanders that Ushijima’s artillery had virtually every inch of ground to the Japanese front bracketed. The numbers of men sent to the rear suffering from combat fatigue soared.

By the end of May, the ground advance had begun to resemble a World War I battlefield, as troops became mired in mud, and rain-flooded roads inhibited evacuation of the wounded. During the struggle for Okinawa, American troops were given two pieces of earthshaking news: President Franklin D. Roosevelt had died on April 12 and Nazi Germany had surrendered on May 8. Unfortunately for them, the war against Japan would continue.

The focus on Okinawa shifted to Sugar Loaf Hill. The hill had not looked especially imposing to the first Marines who advanced toward it, but Ushijima considered it the key to the entire Shuri defenses. Sparsely dotted with shrubs and trees, Sugar Loaf was a height of coral and volcanic rock, 300 yards long and 100 feet high, supported on the southeast by another mound, Half Moon Hill, and to the south by yet another promontory, Horseshoe Ridge. Sugar Loaf was the most visible feature of a three-pronged spear pointed directly at the advancing 6th Marine Division. Each of the three peaks could deliver murderous fire from heavy guns against any other peak attacked by the Marines; attacking troops charging one precipice could be cut down by converging fire from the rest of the triangle. In addition, the entire complex could be raked by Japanese artillery, mortars, and machine guns emplaced on Shuri Hill, where the 1st Marine Division’s advance had been abruptly halted.

Units from the 6th Marine Division advancing toward Sugar Loaf fell into a bloody pattern of doggedly fighting their way to its narrow crest, holding it briefly against fierce counterattacks, then falling back under unbearable pressure. For five straight days the ebb and flow of an ugly war of attrition continued unabated, with the crest of Sugar Loaf changing hands numerous times; more and more dead Marines lay strewn about the bloody approaches. A breakthrough finally took place on May 17, when a Marine battalion seized a large portion of Half Moon Hill, which enabled them to rain down heavy fire support on Sugar Loaf Hill the next day. Japanese artillery on Wana Ridge was being gradually reduced as well by Marine units fighting farther east. On May 18 the Marines launched two diversionary attacks, one against Half Moon and Horseshoe Hills and the other against Sugar Loaf’s right flank, drawing much of the Japanese fire and allowing a force of tanks and infantry to rush around Sugar Loaf’s left flank, attack it from the rear, and rout the remaining Japanese defenders.

Finally, Sugar Loaf fell silent. During the 10-day period up to the capture of Sugar Loaf Hill, the 6th Marine Division lost 2,662 killed or wounded and another 1,289 cases of combat fatigue, about the same number of casualties suffered during the entire fighting at Tarawa. The 29th Regiment suffered 82 percent casualties and essentially ceased to exist. Ushijima, short on troops and supplies, began pulling units out of Wana Draw and the Shuri Line in late May, allowing more Marines to pour into Shuri, many of whom moved over from Sugar Loaf Hill.

“We Never Had a Chance of Victory”

The unrelenting pressure on the Shuri Line convinced Ushijima to withdraw to his final defensive positions on the Kiyamu Peninsula; his troops began moving out on the night of May 23, leaving behind rear elements that continued to slow the American advance. Many Japanese soldiers too wounded to travel were given lethal injections of morphine or were left to die on their own. By May 31 the Americans realized that the Japanese had evacuated large numbers of troops from the Shuri defenses; pursuit continued from late May until June 11. By the first week of June, U.S. forces had captured only 465 enemy soldiers while claiming 62,548 killed. It would take two more weeks of hard fighting and an additional two weeks of mopping-up operations using explosives and flamethrowers before the battle would finally come to an end. In early June, Marines cleared the Oroku Peninsula in the west while Army units destroyed Ushijima’s eastern flank by routing the defenders at Yaeju-Dake. The Japanese survivors, some 30,000 troops who had retreated to the Kiyan Peninsula, now had nowhere to go; two-thirds of them would fight to the death.

Japanese resistance was finally overcome between June 11 and June 21, as soldiers and Marines slowly closed in on remaining pockets of resistance. Of the remaining exhausted Japanese defenders who faced the final onslaught, some one-third made the decision to surrender. The remainder fought to the death, committed suicide with grenades, or were killed in droves making suicidal charges against entrenched American positions. The 2nd Marine Division’s 8th Regiment had come ashore to fill out the 1st Marine Division for the final assaults of the campaign. On June 3, while he was personally reconnoitering the front of the 8th Marines’ position, General Buckner was killed by an enemy artillery barrage. The next senior general officer was Maj. Gen. Roy Geiger, the commander of the Marine forces on Okinawa, who was spot-promoted to lieutenant general and became the first and only Marine naval aviator ever to command an American army in the field.

The Japanese defenses were all but overwhelmed by June 16. Ushijima, realizing that the end was near, dissolved his staff on June 19 and ordered all available troops to go over to guerrilla operations. On June 21, organized resistance came to an end in the 6th Marine Division’s operational zone, which encompassed the southern shore of the island. The 1st Marine Division mounted its final attacks of the campaign, also on June 21, and by nightfall reported that all its objectives had been secured. Units of XXIV Corps made similar announcements, and Geiger declared Okinawa secure on July 2 after an 82-day campaign, although mopping-up operations continued, netting an additional 9,000 enemy dead and 3,800 captured. The last official flag-raising ceremony on a Pacific island battlefield took place at Tenth Army headquarters at 10 am on June 22. Earlier that morning, with 7th Infantry Division troops closing in on their headquarters, Ushijima and Cho, just promoted to lieutenant general, committed ritual suicide; Ushijima had ordered Yahara to escape to Japan and make a final report on the campaign. Just before Cho killed himself, he wrote a note: “Our strategy, tactics, and techniques were all used to the utmost. We fought valiantly, but it was as nothing before the material strength of the enemy.” Yahara, who was captured but eventually returned to Tokyo, later conceded, “The fact was that we never had a chance of victory on Okinawa.”

Heavy Casualties on Both Sides

Weeks before the firing stopped, American construction battalions and engineers, following close on the heels of the ground forces, were hard at work transforming the island into a major base for the projected invasion of the Japanese home islands. Repeated meat-grinder frontal assaults on Okinawa made it the costliest battle of the Pacific War: 34 Allied ships and craft of all types were sunk, most by suicide attackers, and 368 ships and craft were damaged. In addition, the Allied fleet had lost 763 aircraft. Total American casualties in the operation numbered more than 12,000 killed, including 5,000 Navy dead and almost 8,000 Marine and Army dead, and 36,000 wounded. The U.S. Navy suffered the greatest casualties of any operation in its entire history.

Combat stress accounted for large numbers of psychiatric casualties, taking a huge toll on the Americans’ frontline strength. In all, there were more than 26,000 nonbattle (sickness or combat fatigue) casualties. At Okinawa, the rate of combat losses caused by battle stress, expressed as a percentage of those caused by combat wounds, was a staggering 48 percent. By contrast, in the Korean War, fought in the worst terrain conditions American soldiers had yet experienced, the overall rate would be between 20 and 25 percent. American losses were so heavy that several congressional leaders called for an investigation into the conduct of the military commanders. Incredibly, 35 percent of all American combatants who fought at Okinawa became casualties. The horrific cost of taking Okinawa and the specter of repeating the ordeal on an even greater scale by attacking the Japanese mainland weighed heavily in the American decision to use atomic weapons against Japan six weeks later.

Japanese losses were enormous: approximately 100,000 soldiers were officially killed in action and another 23,764 were believed buried by the Japanese themselves. Only 10,755 were captured or surrendered. Many residents of Okinawa fled to mountainous caves where they subsequently were entombed, and the precise number of civilian casualties will never be known. Historians have put the total number of Okinawans killed at close to 100,000, or one-fourth of the total population. Caught between two massive armies, the unfortunate Okinawans perished in a number of ways—from artillery fire, air attacks, starvation, fighting with the Japanese garrisons (either by coercion or by choice), being entombed in the vast number of caves that dotted the island, committing suicide before approaching American soldiers could reach them, or being shot by fanatical Japanese soldiers.

The Japanese lost a total of 7,830 aircraft and 16 combat ships as well as an estimated 2,000 pilots in kamikaze attacks. Altogether, the combined suicide campaign sank 11 American destroyers, one minesweeper, and assorted auxiliary craft and damaged four fleet carriers, three light carriers, 10 battleships, five cruisers, 61 destroyers, and countless support ships. All told, nearly a quarter of a million people were killed or wounded on Okinawa—almost 3,000 per day for every day of the three-month ordeal.

E.B. Sledge, a 1st Marine Division veteran of the battle, left behind a vivid description of the battle’s horrors. “The mud was knee deep in some places for several feet around every corpse, maggots crawled about in the muck and then were washed away by the runoff of the rain,” he wrote. “There wasn’t a tree or bush left. The scene was nothing but mud; shell fire, flooded craters with their silent, pathetic, rotting occupants; knocked-out tanks and amtracs; and discarded equipment—utter desolation. We were in the depths of the abyss, the ultimate horror of war. In the mud and driving rain before Shuri, we were surrounded by maggots and decay. Men struggled and fought and bled in an environment so degrading I believed we had been flung into hell’s own cesspool.”

Of The 7 Gannon boys,including my Dad ( Iwo Jima and Okinawa),that went to WWII from Lima,Ohio…The Eldest George Jr. was killed by a sniper….We also lost the Youngest,Eddie in Germany.

I am currently reading EB Sledge’s book, With The Old Bred. His written accounts of Okinawa and Peleilu are incredible. All of the men who endured so much on those islands, deserve our utmost respect and love!

Side note: The Okinawans, a different ethnic group from the Japanese, never forgave the Japanese for using them as a blockade force against the Americans. I noted this over three decades later when I was assigned to the area.