By John Wukovits

On June 10, 1944, as his troop transport churned through the Pacific toward the Japanese-held island of Saipan, Pharmacist’s Mate First Class Stan Bowen wrote a letter to his sweetheart, Marge McCann. The letter would not be mailed until after Bowen and the Marines had already landed, but he wanted her to know that he was all right. “My Dearest Margie,” he began. “Since you haven’t heard from me in some time you probably know that we’re on our way into combat again. This will be the last letter I’ll be able to write for I don’t know how long but at any rate for some months. But first of all I want you to know how swell I think you are and how much I think of you. Of all the people I’ve ever known you’re one of the swellest and truest, Margie darling. Please don’t worry darling as I’ll be careful and won’t take any unnecessary chances. I’ll have your pictures with me all the time. I’m thinking of you every minute and missing you. I’m not afraid of any thing that lies ahead so don’t you be. All my love always, Stan.”

Like most men heading into battle, Bowen masked his true feelings. A veteran of the frightening clash at Tarawa, he feared that Saipan would be just as bloody, but he was not going to frighten Marge. His comments contrasted starkly with the words of a Marine officer who spoke bluntly to the men he was about to lead into combat on Saipan’s imposing terrain. He told a rapt, if somewhat unsettled, audience on the transport that even before their amphibious tractors reached shore, they would face sharks, barracudas, sea snakes, razor-sharp coral, poison fish, and giant clams. Once ashore, Japanese defenders would proffer a brutal welcome from an island already containing a hostile native population, poisonous snakes, giant lizards, and such dread tropical diseases as leprosy and typhus. As the officer wound up his unnerving talk, a private sheepishly raised his hand and asked, “Sir, why don’t we let the Japs keep the island!”

That question would be asked often by the thousands of Marines and Army infantry preparing to land on Saipan, a part of the Mariana Islands 1,500 miles east of Manila Bay and 1,300 miles southeast of Tokyo. The island itself provided a misleadingly lush backdrop for the desperate struggle to come. Luxuriant blue waters drifted over a surrounding coral reef before surging onto delicate, sandy beaches. Rising slowly from the coastal plains in the south, a succession of bright green hills and plateaus culminated in jagged, sheer cliffs in the north. A veritable smorgasbord of terrain blanketed the island, including swamps, sugarcane fields, steep ravines, jungle-cloaked peaks, and hundreds of limestone and coral caves ideal for defensive bunkers and artillery emplacements.

Battering the Hardened Defenders of Saipan

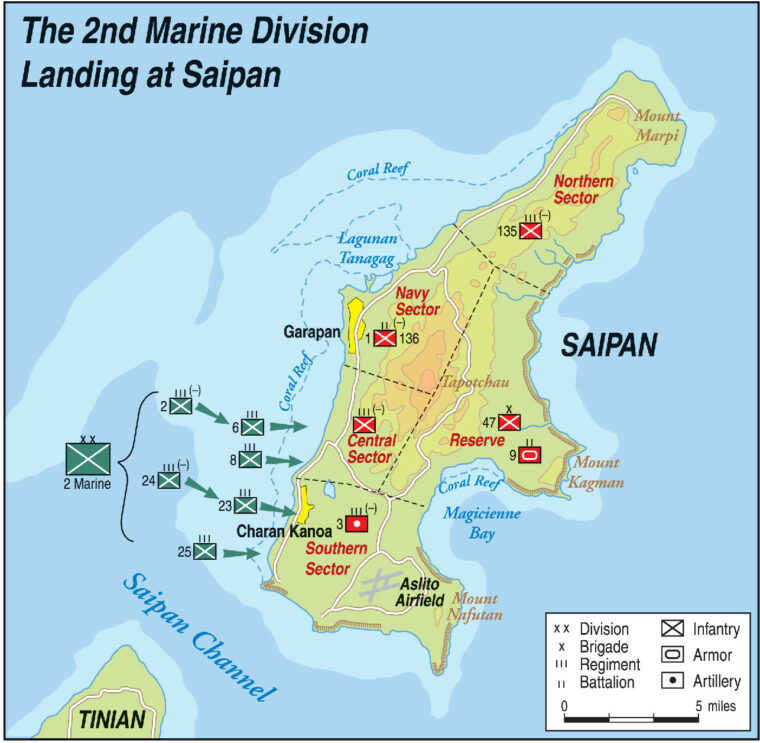

By the late spring of 1944, General Yoshitsugu Saito commanded 31,629 Japanese troops on Saipan, but many of the intended fortifications were still half-complete. This did not worry either Saito or Saipan’s naval commander, Admiral Chuichi Nagumo, who had executed Japan’s stunning attack against Pearl Harbor. They planned to demolish the American invaders at the beaches while the Imperial Navy’s fleet sortied to engage enemy naval forces in the area. Correctly guessing that an American assault would come ashore near the coastal village of Charan Kanoa in the southwest, Saito placed his artillery in nearby hills and on the far side of Mount Fina Susa. He zeroed-in the beaches for accurate artillery and mortar fire, and anchored various colored flags in the water to mark ranges between the reef and the shoreline.

The Japanese had indoctrinated the inhabitants of Saipan to expect a barbaric invader eager for blood. Authorities had begun to evacuate some of the civilians, and fear of the Americans intensified when a U.S. submarine torpedoed and sank a ship carrying 1,700 evacuees. Men and women left on the island worried that they could not save their families from a gruesome death at the hands of the invaders. Meanwhile, an impressive American flotilla gathered to seize Saipan. Possession of the Marianas would hinder Japan’s lines of communication, serve as a staging ground for future assaults and, most importantly, provide bases for the huge American B-29 bombers to commence bombing the Japanese home islands.

Under the overall command of Admiral Raymond A. Spruance, victor of the 1942 Battle of Midway, an enormous force of 535 ships transported 127,571 troops to the target islands in two groups. The Northern Attack Force, headed by Admiral Richmond Kelly Turner and Marine General Holland Smith, was to assault Saipan on June 15, then mop up nearby Tinian afterward. In the meantime, Rear Admiral Richard L. Conolly and Marine Maj. Gen. Roy S. Geiger would recapture the American possession of Guam. Standing in reserve was the U.S. Army’s 27th Infantry Division, under Maj. Gen. Ralph S. Smith.

The landing plans for Saipan seemed simple enough. Armored amphibians, called LVTAs, would first land to clear opposition with their 75mm guns and machine guns. Amphibious tractors, or amtracs, would then crawl over the reef, churn across the beaches, and advance one mile inland before depositing their human cargo of Marines. Simple though it appeared, Smith warned his fellow officers to expect the worst. “We are through with flat atolls now,” he said. “We learned to pulverize atolls, but now we are up against mountains and caves where Japs can dig in. A week from now there will be a lot of dead Marines.”

On June 13, two days before D-day, seven new battleships bombarded Saipan with 2,400 16-inch shells, but their effectiveness suffered because the ships remained beyond a 10,000-yard range to avoid possible offshore mines. Inexperienced gunners and spotters focused the shelling on Saipan’s largest targets, while ignoring hundreds of smaller pillboxes and complexes. The next day, Nagumo stared seaward in astonishment as eight old battleships, the same behemoths his planes had reduced to rubble on December 7, now opened the American attack. Raised from the harbor’s bottom, repaired, and restored to duty, the battleships hurled shell after shell at Saipan’s emplacements. That same day, traitorous radio announcer Tokyo Rose broadcast a threat to the Americans about to hit Saipan. “I’ve got some swell recordings for you just in from the States,” she teased the assault troops. “You’d better enjoy them while you can, because tomorrow at oh-six-hundred you’re hitting Saipan—and we’re ready for you.”

“Our Beach was Hot”

The Navy’s pre-invasion bombardment and air strikes commenced at 7 am on June 15, while Marines of the first waves lingered offshore in amtracs. One officer told his men, “We have been waiting a long time for this D-day. It has arrived. All that remains is our mission. Attack with the same spirit as before, upholding the traditions of this regiment and our Corps. May our dear Lord give us his blessings on this day. The Leathernecks are confident in one thing. Driven as the enemy may be by the task force bombardment, he fears most the assaulting Marine.”

When Turner’s signal to land the landing force flashed at 8:40 am, hundreds of LVTAs churned toward shore, belching shells in rapid succession. Seven hundred amtracs, bulging with troops of the assault waves, followed closely behind, intent on landing the 2nd Marine Division on the left beaches and the 4th Marine Division on the right. As they approached, observers noticed that a thick haze, produced by shells throwing a talcum-like dust into the air, blanketed the beaches. That quickly became a minor irritant, however, compared to the Japanese shells that immediately began landing among the amtracs. Spruance’s flagship, the cruiser Indianapolis, reeled from a hit, and Marines huddling inside the amtracs listened to whistling shells and felt the impact of nearby hits. The multicolored Japanese flags, marking the range for enemy artillery, did little to encourage the Marines. In addition, a solitary Japanese soldier, cleverly posted inside the top of a huge smokestack in the middle of the landing zone, directed fire on the exposed enemy. Several amtracs exploded from direct hits that tossed them head over heels like a fry chef flipping pancakes in a diner.

As he headed toward shore, Bowen stared at the Navy ships booming a greeting to Saipan. Planes strafed and dropped bombs, while huge 14-inch shells lumbered overhead. “All this made it seem like a John Wayne movie scene,” he recalled, “except this was no movie and I was scared because I was ‘battle hardened’ by Tarawa and knew that we were in for a big one this time. God, I thought, I hope the generals and admirals know what they are doing.” First Lieutenant John Chapin recalled the heavy shelling from the Japanese: “The shells really began to pour down on us—ahead, behind, on both sides, and right in our midst. They would come rocketing down with a freight-train roar and then explode with a deafening cataclysm that is beyond description. The fire was hitting us with pin-point accuracy, and it was not hard to see why—towering 1,500 feet above us was Mount Tapotchau, with Jap observation posts honeycombing its crest.”

Bowen made it to Green Beach, but found the sand there even less hospitable than the sea offshore. “Our beach was hot,” he said, “shells exploding all around, and though we were supposed to dig in and wait until the second and third waves hit and get organized, my platoon headed inland right away. I’m glad we did because we’d have had our asses shot off if we stuck around that beach too long.”

Hard Resistance

The Japanese bombardment of the beaches was both accurate and relentless, as fire from Aslito Airfield, Hill 500, and Mount Tapotchau tore into the Marines. Casualties quickly mounted in the face of stiff opposition from Japanese who were fighting, in some places, practically on the beaches. In the center, at Afetna Point, heavy gunfire forced men of the 2nd Marine Division to veer north in an attempt to swing behind enemy positions. Within minutes of their arrival on the northern beaches, all four 2nd Marine assault battalion commanders fell to Japanese bullets. One battalion, struggling to hold a beachhead that extended for only 12 yards, barely avoided being shoved back into the sea. Only a heavy bombardment by supporting battleships enabled them to hold on.

The Marines faced blistering resistance when they attempted to leave the beaches. Second Lieutenant Fred B. Harvey led a platoon up the beach, only to see a saber-waving Japanese officer charge toward him. Harvey blocked the sword with his carbine, then shot the officer. Gunnery Sergeant Keith Renstrom spotted a young Marine lying on the beach with his face pressed into the sand. When Renstrom ran over to see if he was wounded, the frightened boy mumbled, “I can’t move, Gunny; I just can’t move. I’m just too scared.”

By the end of the first day, almost 20,000 Marines guarded a beachhead approximately 10,000 yards long and 1,500 yards deep, half the planned first-day goal. Despite sustaining 2,000 casualties, the Marines were unable to sustain a drive inland. As night approached, they dug in and waited for an expected Japanese counterattack.

Throughout the night the Japanese constantly probed American lines for weak spots. The worst action occurred against the 2nd Division’s left flank, where Bowen was huddled, when more than a thousand Japanese charged the American lines. Three destroyers edged closer to shore to fire star shells over the Japanese, and in the eerie light American tanks, destroyer gunfire, and hand-to-hand fighting finally repelled the attack. Afterward, 700 Japanese bodies littered the area in front of Bowen and his comrades. “God was with me that night,” Bowen recalled. He remembered one sergeant who, though badly wounded in the leg, continued to alternately fire his M1 and swear at the Japanese. Bowen rushed over to treat him and applied a tourniquet to his leg, and during the entire time the sergeant never stopped cursing or shooting.

Turning the Night into Day

On June 16 the Marines slowly advanced inland, reaching by day’s end a ridge overlooking Aslito Airfield. On the beaches, other Marines unloaded mountains of supplies that were crucial to the drive. That night, Saito unleashed the first night tank attack of the Pacific conflict as 40 tanks laden with soldiers streamed from a ravine and crossed open fields. Japanese commanders barked orders from the open turrets of the tanks, and some leapt from their vehicles and waved swords to encourage their men.

The Marines had their own secret weapon ready—star shells fired from destroyers transformed night into day and made the enemy easy targets. A Japanese soldier lamented, “Every time we try a night attack, they turn the night into day.” One machine-gun crew fired 10,000 rounds at charging enemy soldiers. Nearby, a Marine colonel calmly sat on a tree stump amid heavy fire, puffing a cigar and directing naval gunfire onto the approaching tanks. Bazookas and American tank fire tore into the swarming Japanese at point-blank range, yet in many spots even that was insufficient. Marines ducked into foxholes as enemy tanks rolled overhead, leaking oil onto their uniforms. Other Marines halted tanks by jamming wooden planks into their treads, then dropping grenades down their hatches as Japanese officers emerged to see what had happened. Private Robert S. Reed received the Navy Cross for destroying four tanks with a rocket launcher and a fifth with a grenade. When the battle ended, 300 Japanese lay dead and the burning hulks of 28 tanks clouded the air.

Meanwhile, developments at sea cast a pall over the operation. Spruance met with Holland Smith and Kelly Turner on June 16 to inform them that American submarines had spotted the Japanese fleet heading toward Saipan. Spruance asked Turner to move every possible transport away from Saipan while he steamed seaward to meet the foe. Smith hated to lose naval support and supplies for his men ashore, but admitted that the move was necessary under the circumstances. If Spruance halted the Japanese fleet, Smith’s job on Saipan would be easier against a trapped and unsupported Saito.

Taking Hill 500

When Bowen and other Marines and Army infantry stirred the next morning, they could hardly believe their eyes. The Navy they had relied on to provide gunfire support and bring in supplies had vanished overnight. “We woke up one morning, on the mountainside, and were shocked to look down and see the harbor empty of ships, only a few transports,” recalled Bowen. “No battle wagons, cruisers, destroyers. They’d left us, we thought. A very eerie feeling, left alone on the island.” Bowen’s concern rose on the night of June 19-20 when “we heard deep, low, heavy booms way off and realized that a big naval battle was going on and if we lost it, we were in deep, deep trouble.” Before long, Bowen’s fears dissipated as Spruance returned following a victory. “But one morning, a day or so later, the harbor was full of those beautiful American war ships again. They’d met the Jap Navy and kicked their butts good.”

While Spruance slugged it out with the Japanese in the Battle of the Philippine Sea, Army and Marine units steadily advanced across Saipan. Hill 500, offering a commanding view of the southern part of the island, became an especially bloody battleground where soldiers from both sides struggled in vicious hand-to-hand combat.

Private First Class Joseph Falcone, Jr., wrote home that the fighting “was terrible and I lost quite a few of my close buddies. Out of my whole crowd that really stuck together there is just me, Mac and the guy from Tennessee that I told you about. I was plenty scared this time and I guess everyone was especially the first 3 days when they were shelling us with artillery. All you can do is get into a foxhole and pray that one don’t fall in with you. And I prayed a lot.”

Corporal William Ruch, Jr., was huddled in foxhole with a buddy during a lull when they decided to clean their rifles. Ruch field-stripped and cleaned his M1, then stood guard while his buddy tended to his. Just then a Japanese mortar barrage erupted and shells exploded on all sides. One whistled so close that Ruch shouted, “This one is ours!” His buddy, who had put his rifle parts in his helmet while he cleaned his rifle, tossed his helmet on his head and lay flat on the ground. The shell hit three feet away and knocked the wind out of them both, but otherwise left the two Marines untouched. For the next few minutes the pair scrounged around in the dirt, locating their missing rifle parts. After they finished, Ruch peered from the foxhole and saw a gruesome sight. A Japanese tank commander, standing in his turret, had had his head severed by Marine machine gunners who “cut it completely off. I saw it roll down the tank side.”

A Subterranean Campaign

By June 20, the lower third of Saipan had been taken, except for one strong Japanese force in the southeast at Nafutan Point. Holland Smith turned the axis of his attack north, where Saito’s troops waited in prepared defensive positions. The 2nd Division moved along Saipan’s west coast, the 4th Division along the east, with Ralph Smith’s 27th Infantry Division advancing in the middle. Progress was slow. Emperor Hirohito had dispatched a special message to the defenders, emphasizing the importance of continued resistance. “If Saipan is lost,” warned the emperor, “air raids on Tokyo will take place often. Therefore, you will hold Saipan.” Saito prepared to do his best, but as an added precaution he also began burning his secret papers.

News that Spruance had routed the Imperial Japanese Navy meant that 20,000 Japanese soldiers on Saipan were now trapped, with no hope for reinforcements or resupply. All they could do was exact a gruesome price for each yard they lost. Tank officer Tokuzo Matsuya somberly wrote in his diary that when the enemy appeared, “I will take out my sword and slash, slash, slash at him as long as I last, thus ending my life of 24 years.” American troops were about to face combat at its worst. The Japanese waited in cleverly camouflaged positions in a series of caves, hills, cliff and ravines. The only way to pry them out was to cautiously approach and drop explosives or burn them out with flamethrowers. The fighting turned into a struggle that one general called a “war such as nobody had fought before, a subterranean campaign in which men climbed, crawled, clubbed, shot, burned and bayoneted each other to death.”

Two Smiths, Two Doctrines

A three-division attack opened on June 23, with the 2nd Marine Division on the left, the 27th Infantry Division in the middle, and the 4th Marine Division on the right. The Marines advanced rapidly, but the 27th, facing horrible terrain and heavy opposition in places aptly named Hell’s Pocket, Death Valley, and Purple Heart Ridge, soon bogged down. Since the Marine flanks were now exposed, their drives along the east coast and up Mount Tapotchau had slowed. Holland Smith, who held a low opinion of the 27th’s leaders from previous campaigns and from what he considered an ineffectual showing against the Japanese at Nafutan Point, exploded and asked Maj. Gen. Sanderford Jarman, the senior Army officer on Saipan, to speak with Ralph Smith about prodding his men to make better progress. Smith promised Jarman that on the following morning he would personally stand at the jump-off point to encourage his men, and added that he should be relieved of command if he did not improve his men’s performance.

Differing military philosophies contributed to the dispute that flared between the Army Smith and the Marine Smith. Army doctrine emphasized conservation of strength and the use of artillery and air power to eliminate obstacles. The Marines, however, were trained to quickly secure a beachhead so that their supporting naval forces could leave highly vulnerable offshore positions. They preferred to bypass pockets of resistance and grab ground fast.

The next morning, true to his word, Ralph Smith stood at the front when the three divisions jumped off. The Army infantry fought well, but Saipan’s Death Valley, flanked by steep, fortified hills and cliffs, proved a difficult nut to crack. Faster advances by Marines on either side made the 27th’s efforts appear lame in comparison. The American front line, shaped in a large U, with Marine units forming the arms and the 27th the base, had to be stabilized to avoid catastrophe. Holland Smith begged Spruance to replace Ralph Smith with someone who could get the 27th moving. Spruance agreed and relieved Ralph Smith. The move provoked bitterness on both sides. Army supporters claimed that Holland Smith simply wanted the Army to throw away lives in a reckless fashion, while Marine defenders responded that Ralph Smith’s incompetence proved to be his downfall.

The day following Smith’s relief, Army and Marine units progressed up the island. Marines captured the summit of lofty Mount Tapotchau under the aggressive leadership of General Thomas Watson, who prodded one hesitant officer by bellowing, “There’s not a damn thing up on that hill but some Japs with machine guns and mortars. Now get the hell up there and get them!” Amazed troops looked down upon the landing beaches from Tapotchau’s commanding view and realized how lucky they had been. “Every time I look back at the beach from here,” mused one Marine sergeant, “I wonder how any of us got ashore. The Japs could see every move we made.”

The Japanese might have been retreating before superior American power, but they retained plenty of fight. During the night of June 26-27, 500 Japanese broke out from Nafutan Point, each determined to kill seven Americans before dying. They charged headlong into a battalion of the 27th, reaching as far as they airfield and killing Americans as they slept before a hastily assembled force of Seabees, engineers, and Air Force personnel blunted the attack.

Civilians Caught in the Crossfire

By June 30 Army units completed the difficult task of sweeping the Japanese out of Death Valley, sustaining well over a thousand casualties in a week’s worth of bitter fighting. Marine units also advanced, suffering equally heavy losses. Marines and Army infantry faced gut-wrenching decisions whenever they spotted groups of civilians. Should they shoot in case Japanese soldiers hid in their midst, or should they hold their fire? No instruction manual taught them what to do in such unusual circumstances. First Lieutenant Frederic A. Stott, in the 1st Battalion, 24th Marines, recalled one time when the men refrained from shooting. “Using civilian men, women, and children as decoys, the Jap soldiers managed to entice a volunteer patrol forward into the open to collect additional civilian prisoners. A dozen men from A Company were riddled as the ruse succeeded.”

Despite the Japanese perfidy, many Americans showed mercy on the battlefield. Private First Class Falcone and others were heading through the jungle to attack a hill when they heard noises. They were prepared to shoot when someone shouted that the noise, which came from beneath a blanket lying on the ground, sounded like the cries of a baby. “We walked over and took the blanket off and it was a Japanese girl about 20 years old holding the baby in her arms,” Falcone recalled. “We tried to take the baby away from her but she wouldn’t give it up. We had a heck of a time trying to convince her that we wouldn’t hurt her or the baby. She couldn’t walk because her heel was blown off and I had to carry her out while this guy, Charlie, carried the baby. They finally put her in a jeep and I guess she was taken care of. And what a cute baby it was. It really made me think a heck of a lot about it being like that back home and how thankful we should all be that it isn’t.”

A Brutal Banzai Charge

With most of central Saipan now in American hands, Saito withdrew to his final positions in the north. Medics handed out grenades to those too badly wounded to walk—one grenade for every eight patients—while officers praised them for their willingness to die an honorable death. The final American push started on July 2, with the 27th and 4th Divisions advancing against the Japanese in the northeast while the 2nd moved toward the town of Garapan and Tanapag Harbor on the west. Holland Smith beamed at the progress of all units and commended both Army and Marine outfits on July 4, adding, “It is fitting that on the 4th of July you should be extremely proud of your achievements.”

Saito and Nagumo knew that the end was near. From his sixth and final headquarters cave, an exhausted Saito issued his last order on July 6. Praising his troops for staging such a courageous defense, he called for one final thrust against the enemy to show the true spirit of Japan. The weakened commander, however, chose not to accompany his men in this suicidal charge. After a last dinner of canned crabmeat and sake, Saito entered a small cave. Bowing toward Japan, he saluted the emperor with his sword, then pricked himself in the stomach to draw ceremonial blood before an aide shot him through the head. Nagumo, who had tasted glorious moments on December 7, 1941, opted for the same end shortly afterward.

Later that night, 3,000 Japanese soldiers, civilians, and sailors, many wobbling on canes and crutches, gathered for a banzai attack. Since weapons were in short supply, some officers gave away their pistols and used their swords. Rifles, clubs, bayonets attached to long sticks, sharpened bamboo poles, and daggers supplanted machine guns and mortars. At dawn on July 7, three columns of Japanese moved toward American lines, singing a Japanese funeral dirge. They quickly punched a gap through two battalions of the 27th Division and swung behind the stunned foe. In the bloody fighting that ensued, swords flashed, bayonets stabbed and slashed, and Japanese and American soldiers fought hand-to-hand.

Lieutenant Colonel William J. O’Brien, commander of the 1st Battalion, 27th Infantry, blazed away at the enemy with pistols in both hands until he ran out of ammunition. Seriously wounded, he jumped onto a jeep and continued firing with its .50-caliber machine gun until that, too, ran out of bullets. The officer finally grabbed a saber from a charging Japanese and slashed at his opponents until he was literally cut to pieces. Near his sliced body, circling the jeep, lay 30 slain Japanese. O’Brien was awarded a posthumous Medal of Honor. Another man from O’Brien’s unit, Sergeant Thomas Baker, wounded and unable to move, asked his men to prop him against a tree and hand him a pistol. Ordering them to fall back, Baker provided cover by firing at the Japanese until he, too, was overrun and killed. His body was found under the tree the next morning, with eight dead Japanese at his feet.

Marine and Army units retreated piecemeal, with the enemy rushing madly among them. In some places, officers organized defensive perimeters, particularly at Tanapag, where Army infantry fought with their backs to the sea. Wounded men helped out by crawling among the dead to retrieve precious ammunition. Private First Class Frank Howarth of the 1st Battalion, 6th Marines found himself and another Marine embroiled in a savage bayonet fight with two Japanese. One soldier slashed both of Howarth’s arms. As the Japanese soldier began to thrust a third time, Howarth lunged to the left, ignored the huge rip in his dungarees caused by the foe’s blade, then rammed his bayonet deep through the man’s chest. Howarth spotted the other Japanese soldier rushing toward him, but when he tried to wiggle his bayonet free from the first soldier’s ribs, it would not come loose. The enemy soldier bayoneted Howarth once in the ribs and twice near his spine, sending him falling helplessly into a foxhole. Just as the Japanese soldier was about to kill him, Howarth’s buddy came to his rescue by smacking the Japanese on the head with his rifle butt. Three hours later a corpsman finally reached Howarth’s position and had him evacuated.

Tragedy in Victory at Saipan

Army and Marine fighters suffered appalling casualties in repelling the banzai charge. The 1st and 2nd Battalions of the 27th Infantry Division lost 918 killed and wounded. Only 189 men were strong enough to answer the next roll call. Japanese resistance all but ended after the final banzai attack, and the American military declared Saipan secure on July 9. Unfortunately, it was too late for one of Bowen’s sergeants, who had seen heavy action earlier at Guadalcanal and Tarawa. The Marine was due to go home the next day, where he intended to marry a girl who had patiently waited three years for him. The man volunteered for one last patrol cleaning out caves. As he stepped toward one cave, fire ripped into him from inside. Bowen rushed to treat the popular sergeant, but unfortunately there was nothing he could do to save his life. Enraged, the rest of the unit unloaded everything they had into the cave.

One final tragedy remained. Thousands of civilians jammed onto Saipan’s northernmost spot, Marpi Point, and refused to surrender. Believing that they would be tortured by the Americans, the civilians carried out agonizing scenes of suicide while American soldiers watched helplessly. Selecting either the 80-foot bluff known as Banzai Cliff or the 1,000-foot Suicide Cliff, the civilians leaped to their deaths on the jagged rocks below. Some families gathered together and blew themselves up with grenades. Captured civilians pleaded through loudspeakers to cease the senseless slaughter, but to no avail. Bowen watched in horror as, one after the other, civilians opted for death over surrender. “The worst of the caves were over on the high cliffs above the rocks and the ocean,” he said. “Hundreds of natives and Jap soldiers were hiding in them. The Japs had so propagandized the natives that we were horrified to see women throw their babies down on the rocks and then jump themselves. The cliffs were real high and you could see the bodies hurtle down to their deaths. A gruesome sight!”

In all, the Marine and Army units suffered more than 14,000 casualties in wresting Saipan from the Japanese. Of the 30,000 Japanese defenders, only 1,000 survived. The high cost reaped huge dividends. Americans had finally breached Japan’s inner defense ring and established air bases from which B-29 bombers could reach the Japanese home islands. The shock waves emitted by the fall of Saipan, combined with Spruance’s victory at sea, forced Premier Hideki Tojo to resign. His compatriot Nagano, the supreme naval adviser to the emperor, gloomily acknowledged the extent of the disaster. “Hell is upon us,” he said. Soon enough, it would be.

I HAVE AN OLD PHOTO OF HILL 500 SAIPAN.SHOWS A SOLDIER HOLDING A MACHINE GUN, ALSO A PLANE IN THE WOODS BEHIND HIM, I WOULD LIKE TO DONATE, ON BACK OF PHOTO IT SAYS MY BUDDY ON HILL 500.