By Al Hemingway

In the early morning hours of May 27, 1918, the earth trembled and the air was filled with a deafening roar as 4,000 German artillery pieces let loose a tremendous barrage on Allied lines. British forces, entrenched between Soissons and Rheims, France, took the brunt of the savage bombardment, suffering horrendous casualties. The blame for their losses rested on the shoulders of one man: General Denis Duchene, commanding general of the French Sixth Army. Duchene had disobeyed orders from Henri-Philippe Petain, French commander in chief, not to mass troops in forward trenches where they would be vulnerable to just such an artillery barrage. Following a subsequent gas attack, 17 German divisions breached the lines and poured through a three-mile-wide gap, reaching the Marne River and threatening the French capital of Paris for the first time in nearly four years.

“Granite Character”

The so-called Aisne Offensive, the brainchild of Quartermaster General Erich Ludendorff of the German high command, seemed to be working perfectly. Ludendorff, an aloof individual with what was described as “granite character,” had implemented the third of five such strategies to win the war before the newly arrived American troops could be put into line. After nearly four years of unprecedented bloody conflict, all sides had fought to an exhausted stalemate, expending huge amounts of manpower in the process. With the signing of a separate peace treaty between Germany and Russia, thousands of additional German units were freed and transferred to the western theater of operations. With the arrival of the Yanks, however, Ludendorff realized that the enemy’s fresh reinforcements could tip the scales in the Allies’ favor and provide the Americans, British, and French with an ultimate victory. He decided to act before this happened, launching a series of huge offensive operations to bring a quick end to the decidedly slow war and insure a final German triumph.

Petain threw all the available French reinforcements he could at the Germans to slow down their advance. It was useless—the German juggernaut smashed the French troops and sent the army retreating toward Paris. “It was like dropping water on a hot stove, they would disappear,” Petain would say afterward of his lost troops.

To Save Paris

To save the beloved capital and win the war, Petain had no alternative but to call on the untested Americans. The 1st and 3rd Divisions of the American Expeditionary Forces (AEF), under the command of General John J. “Black Jack” Pershing, were quickly sent to close the gap. The 1st Division, “the Big Red One,” drove back the elite German 18th Army at Cantigny, the first American victory over the enemy, and took Soissons in July with heavy losses. The 3rd Division fought an equally heroic battle at Chateau Thierry and another violent engagement along the banks of the Marne River, earning the division the nickname “the Rock of the Marne.”

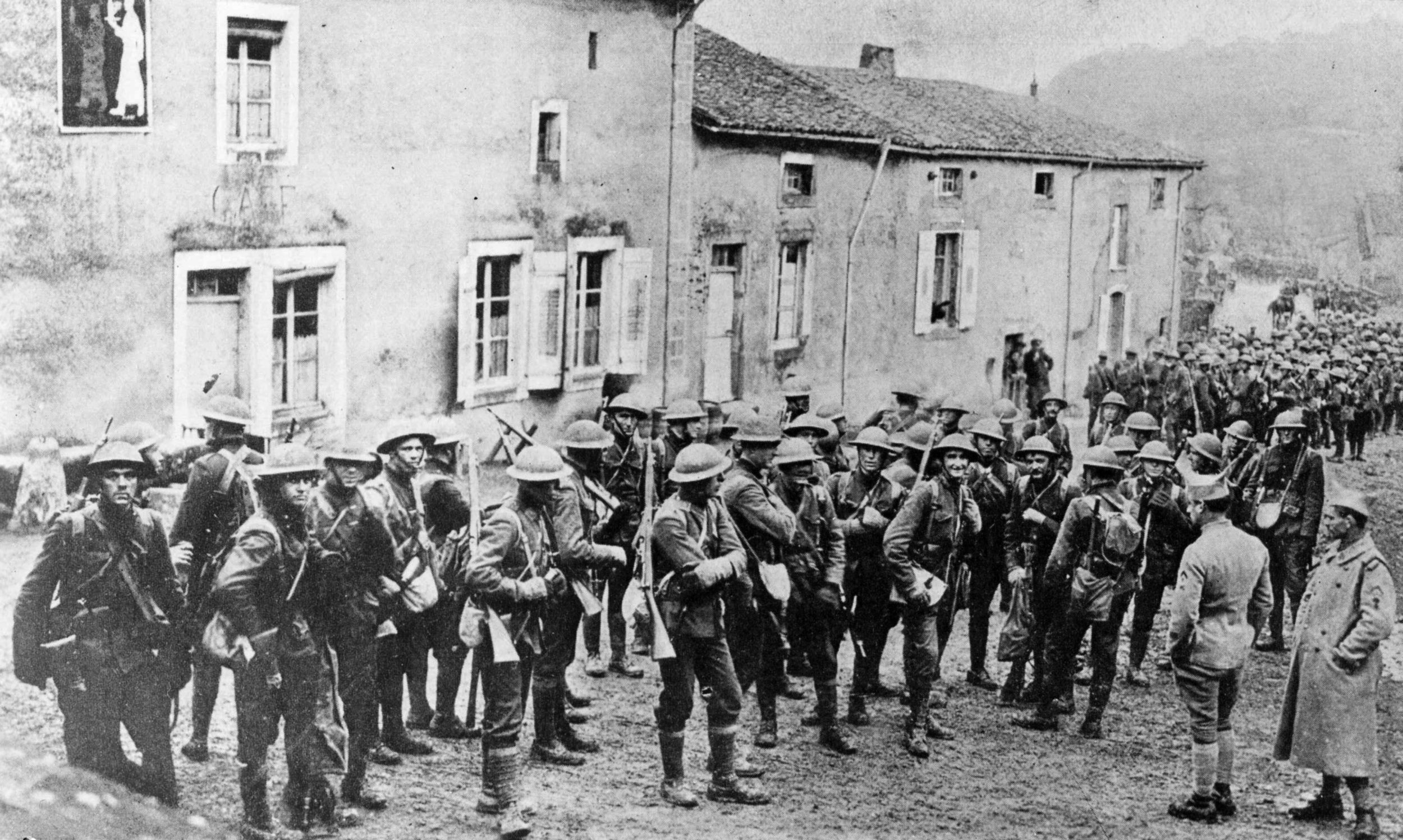

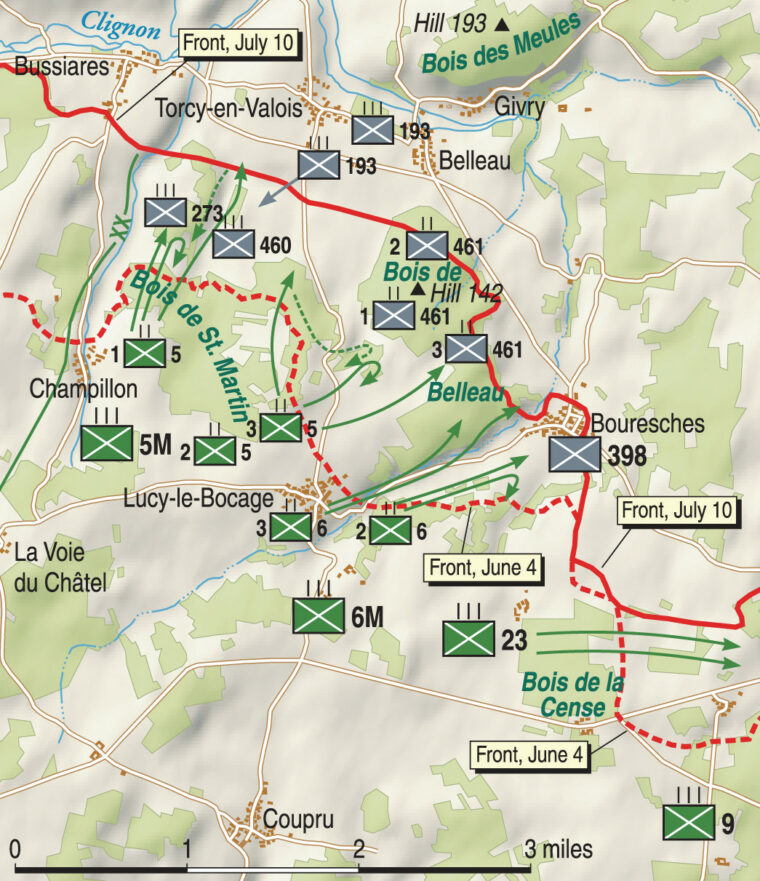

Meanwhile, the 2nd, or Indianhead, Division, comprising the 9th and 23rd Army Regiments and the 2nd Marine Brigade, which included the 5th and 6th Marines and the 6th Machine Gun Battalion, were ordered to move forward as well. Initially, Marine Brig. Gen. Charles A. Doyen led the brigade. He was well liked by his men and had trained them to a high state of efficiency. Unexpectedly, Army Brig. Gen. James G. Harbord, a veteran of the Philippine Insurrection and the Mexican Expedition to locate Pancho Villa, took over the unit from Doyen. It caused some grumbling in the ranks.

Despite the ensuing chaos, the infantry began boarding camions in the early morning hours of May 31 for the town of Meaux, 50 miles away. It was soon learned that the division was not reinforcing another American outfit, but was being put into the hole created by the French withdrawal after the recent German onslaught. The entire French line was crumbling fast, and the 2nd Division was given the unenviable task of stopping the Germans and assisting the other units in saving Paris.

Confusion Within High Command

The liaison between the American division and the French military hierarchy was poor, to say the least. Contradictory orders pertaining to unit locations and movements of supplies and artillery were, at best, fragmentary. In the preceding 12 hours alone, the division had received four sets of conflicting orders from the French command. While visiting the French XXI Corps, where the 2nd Division had been assigned, Maj. Gen. Omar Bundy, division commander, and Colonel Preston Brown, division chief of staff, were infuriated to discover that the French wanted to insert the Americans piecemeal into the battle. Both Bundy and Brown were adamantly opposed to the plan and insisted that their men would fight only after their own artillery and machine gun support had arrived. When corps commander General Jean-Marie Deugoutte asked nervously if the American troops could hold, Brown replied witheringly: “General, those are American regulars. In a hundred and fifty years they have never been beaten. They will hold.”

As the soldiers and Marines pressed toward the front, they encountered thousands of downtrodden refugees choking the road as the troop-laden camions attempted to make their way through the crowd of fleeing civilians. “There were women, old men, and babies, all wandering like lost souls in a chaos of confusion,” wrote Sergeant Martin Gulberg of 75th Company, 1st Battalion, 6th Marines. “Everything and everybody seemed to be in a hurry to get away from the battle line except a few Marines.” Among the hordes of people were dazed and shell-shocked French military trying to escape. As the Americans paraded past them, the battle-weary French soldiers shouted: “La guerre est fini [The war is over].” But to the Americans, the war had just begun. Tired of drilling and practicing maneuvers, they yearned for action—and action they would soon get.

By June 1, the entire 2nd Division occupied a defensive position that ran from Vaux in the southeast all the way to Marigny. The Marines’ position was across the Paris-Metz highway, denying access to the German forces. The center of the line was located at Lucy-le-Bocage. On the Marines’ left was the U.S. 23rd Regiment, and on their right flank the 9th Regiment.

“Retreat, Hell! We Just Got Here!”

As the units settled in for the upcoming battle, French stragglers from the 43rd Division stumbled through their lines. The 43rd had unsuccessfully defended Clignon and was falling back. “Beaucoup d’allemands [Many Germans]!” they would yell as they passed through. When one French soldier strongly advised Captain Lloyd W. Williams of the 51st Company, 2nd Battalion, 5th Marines to retreat, the young officer snapped, “Retreat, hell! We just got here!”

On June 2 the Germans inched their way toward the Marines’ lines. Fierce fighting ensued. Major Thomas Holcomb, commanding officer of the 2nd Battalion, 6th Marines, notified the regimental commander, Colonel Albertus W. Catlin, of “the enemy attacking along our whole front. They were about twelve hundred yards from our position.” Harbord immediately thought that Holcomb’s men were retreating and grabbed a field telephone to order him to remain. Holcomb informed Harbord that his troops had not, in fact, relinquished their positions and added: “When this outfit runs it will be in the other direction. Nothing doing in the fall back business.”

The entire 2nd Battalion, 5th Marines, occupied positions at Les Mares Farm, a mere 30 miles from Paris. This point would be the nearest the German Army would get to the French capital during the battle. The riflemen dug deeper as the enemy artillery lobbed shells at the Marine lines. One curious private peered over the foxhole and a piece of shrapnel decapitated him. Several other Marines were evacuated because of shell shock, a malady that occurred frequently during World War I when the constant whistle of shells and delayed explosions played havoc with one’s nervous system. Several French soldiers also suffering from the mental disorder were seen in the nearby woods, “walking around with rosary beads saying prayers.”

German assaults increased in frequency but were driven back by the American machine gunners who raked their lines and reported proudly that “dead Germans piled the slopes.” For the next several days, Les Mares Farm would see savage combat between the two adversaries. The area was soon dubbed “the Bloody Angle of the AEF.”

Holding Back the Germans

Up to this point, the Germans had enjoyed battlefield success by rolling over the exhausted French units in their way. Now, with Paris so close, they had met with greater resistance—they could not figure out what troops they were facing. By late morning on June 3, more German forces massed for an apparent attack in front of 75th Company, 1st Battalion, 6th Marines. They began to move ominously toward the leathernecks’ lines; soon rifle and automatic weapons tore into their ranks. Sergeant Gulberg would later write in his journal: “Three times they tried to break through, but our fire was too accurate and too heavy for them. It was terrible in its effectiveness. They fell by the scores, there among the poppies and the wheat.”

Soon, the tempo of the shelling picked up and the enemy began a rolling barrage toward the Marines’ lines. The distinctive shape of German helmets could be seen as they advanced along the front, bayonets at the ready, to do battle with the leathernecks. “The devils are coming on,” shouted Captain John Blanchfield. “You have been waiting for them for a year. Now go get them.” Enemy soldiers began falling at a rapid rate and the assault soon fizzled out. The veteran Germans began to find any available cover to escape the accurate firing, while their own gunners were busy providing cover for their comrades.

A platoon from the 55th Company, 2nd Battalion, 5th Marines took up positions in farmhouses and other available structures to prevent the enemy from penetrating through an opening on their right flank. Their deadly marksmanship paid off as they foiled the enemy’s efforts to take advantage of the hole in their perimeter. One senior noncommissioned officer calmly paced behind his men, pointing out prospective targets and offering words of encouragement as they decimated the Germans. As darkness approached, the much-needed automatic weapons of the 8th, 15th, and 81st Machine Gun Battalions arrived and set up positions to support the infantry. At the same time, the Army’s 12th Field Artillery arrived and established forward emplacements to harass the enemy as well.

Thwarted in their attempt to smash the American lines, the Germans began moving up reinforcements to bolster their drive to seize Paris and, hopefully, sue for peace. The 461st Regiment joined the German 10th Division and occupied the southwest corner of Belleau Wood and the southerly area near Hill 181. The enemy also moved into the western sector of the forest and dispatched patrols north of the town of Lucy-le-Bocage. They discovered a dead Marine and quickly brought the body back so that their intelligence teams could analyze the uniform and find out what units they had been facing for the past several days.

Getting bolder in their efforts to punch a hole in the American perimeter, the Saxon 26th Jager Battalion began preparing defensive positions in a wheat field near Les Mares Farm. Fearing that the Germans were getting ready to mount another all-out attack, Corporal Francis J. Dockx and three other Marines edged their way toward the enemy lines. The scouting party ran headlong into a 30-man German patrol accompanied by several machine guns. As they were repulsing the Germans, Gunnery Sergeant David L. Buford and several other Marines rushed to their aid. Buford, a crack shot, took careful aim and dropped seven enemy soldiers before they ran. When they charged the enemy’s automatic weapons, Dockx and another leatherneck were killed. Only five Germans survived; the rest were taken prisoner and returned for interrogation. This was the closest the Germans would get to the French capital during the entire battle.

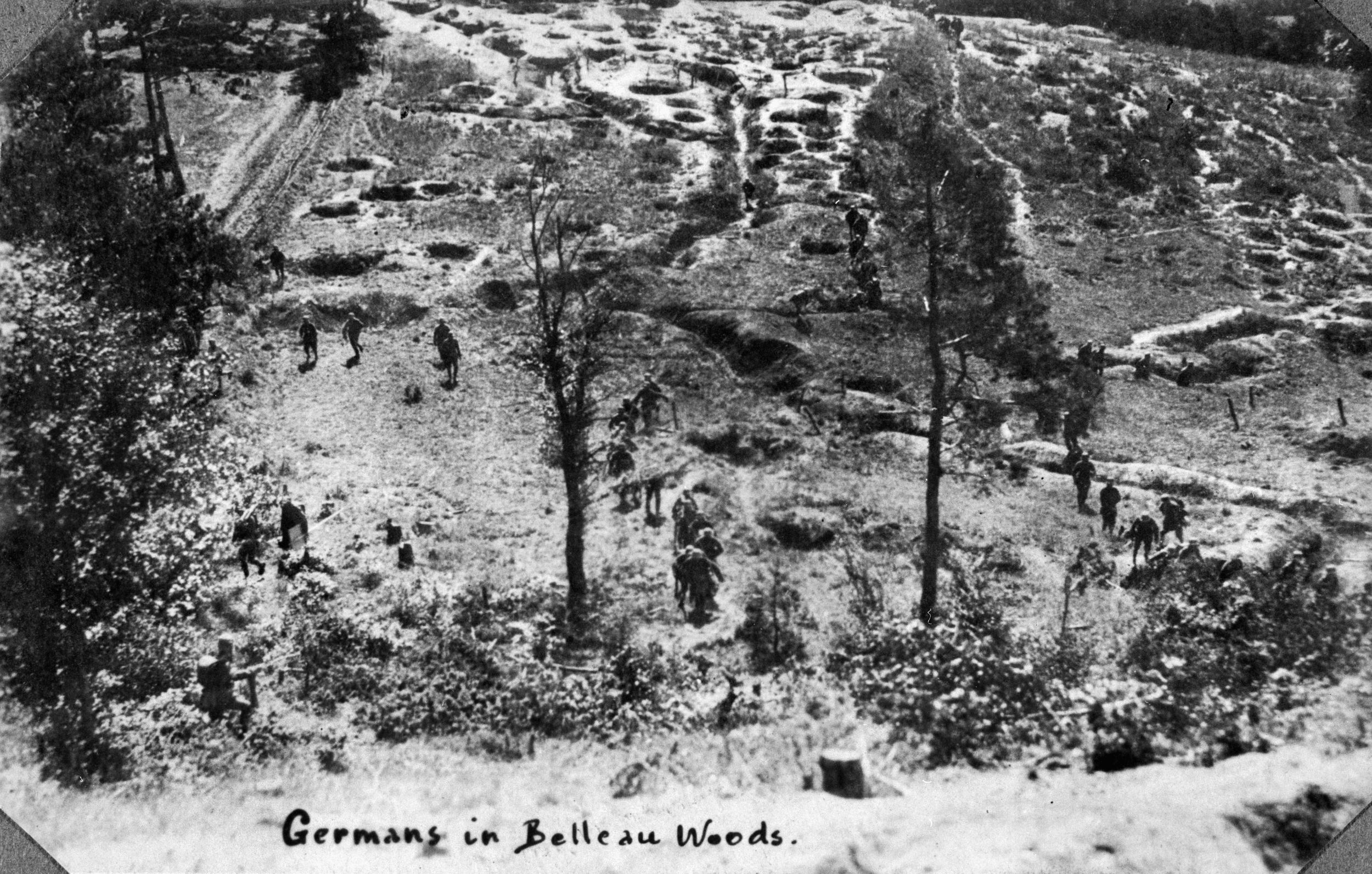

Leathernecks Assault Belleau Woods

On Wednesday, June 5, orders were received at headquarters informing Harbord that his brigade would mount a major assault the following morning. Major Julius S. Turrill’s 1st Battalion, 5th Marines would strike at Hill 142, while the 3rd Battalion, 5th Marines and 3rd Battalion, 6th Marines would rush Belleau Wood. The plan looked wonderful on paper, but there were some important items not addressed. First, two of Turrill’s companies had been taken from him and he was woefully understrength. Second, the French unit that was to participate in the assault was misplaced. Also, no one had done an in-depth reconnaissance of the area. French intelligence reported that it was “lightly held.” It was anything but lightly held—the Germans had dug in and were grimly waiting for the Americans to attack.

On Thursday, June 6, the attack was scheduled to jump off with First Lieutenant George W. Hamilton’s 49th Company of the 1st Battalion, 5th Marines on the right proceeding along the ridge and moving into a ravine that bordered Hill 142, which was completely covered with thick brush and small trees. The 67th Company, led by First Lieutenant Orlando Crowther, would advance on the left and move into the ravine to keep pace with the French, who were also involved in the attack.

When the whistle was sounded signaling the attack, the men stepped forward to begin the assault on the woods. “The air snapped and cracked all around,” wrote Captain John W. Thomason, Jr. “The sergeant beside the lieutenant stopped, looked at him with a frozen, foolish smile, and crumpled into a heap of old clothes. Something took the kneecap off the lieutenant’s right knee and his leg buckled under him. He noticed, as he fell sideways, that all his men were tumbling over like duckpins; there was one fellow that spun around twice, and went over backward with his arms up. Then the wheat shut him in, and he heard cries and a moaning. He observed curiously that he was making some of the noise himself.”

The leathernecks had run into a steady stream of Maxim machine gun fire from the 9th, 10th, and 11th Companies of the German 460th Infantry Regiment. The much-dreaded Maxims could fire 500 rounds per minute. Witnessing his fellow Marines being slaughtered, Private Joseph M. Baker of the 67th Company picked off several Germans and assaulted one gun emplacement single-handedly. He was later presented with both a Distinguished Service Cross and a Navy Cross for his remarkable courage under fire.

Although sustaining numerous casualties, the Marines had taken their initial objectives—with the exception of the square woods. The fighting had been at close quarters, and they used rifle butts, bayonets, and fists. One letter retrieved from the corpse of a German soldier, said, “The Americans are savages. They kill everything that moves.” The battalion, or what remained of it, was consolidated and continued to repel enemy thrusts throughout the rest of the day. Although they had succeeded in driving the Germans from the hill (in fact, their momentum had taken them to Torcy, a small hamlet north of Hill 142), they suffered 333 killed, wounded, and missing in the process.

Late that afternoon, the 3rd Battalion, 5th Marines, under the leadership of Major Benjamin S. Berry, started their movement across a wheat field under the guns of the enemy; their objective was to take the Bois de Belleau. In “an almost perfect skirmish line,” the 45th, 16th, 20th, and 47th Companies inched their way forward toward Belleau Wood in the afternoon sun. The infantrymen soon ran headlong into the crack 461st German Infantry Regiment. The enemy’s 1,141 rifles and Maxims, with interlocking fields of fire, began cutting down the Marines at an alarming rate. Berry sent a message to Harbord informing him of the terrible events: “What is left of the battalion is in woods close by. Do not know whether will be able to stand or not. Increase artillery range.” Berry himself sustained a debilitating wound when a bullet ripped into his left elbow and lodged itself in the palm of his hand. He continued to lead the battalion until the excruciating pain forced him to relinquish his command to Captain Henry Larsen.

The Marines’ Worst Day of Fighting

While the 5th Marines were slugging it out with the Germans, the 3rd Battalion, 6th Marines had also stepped into the midst of the fight. Four companies set out to beat back the enemy at Bouresches, on the German left, and take the all-important railway station there. Once again, the combat was relentless and at close quarters as Marine riflemen stabbed, slashed, and cut their way through the seemingly impenetrable German defenses in the woods. Enemy Maxims caused numerous casualties as each gun position had to be eliminated one by one. Colonel Catlin, commanding the 6th Marines, was struck in the chest by a round that sent him spinning like a top. Captain Tribot-Laspierre, the French liaison officer to the regiment, pulled him out of harm’s way.

When their forward motion came to a screeching halt, Harbord called upon Major Thomas Holcomb’s 2nd Battalion, 6th Marines to seize the town and its railroad station. Captain Donald Duncan’s 96th Company, supported by three platoons from Captain Randolph T. Zane’s 79th Company, swung into action. As the infantrymen fell from the hailstorm of German machine gun and artillery fire, Lieutenant (j.g.) Weedon Osborne, a U.S. Navy dentist, ran among the wounded giving them first aid. An artillery round exploded, killing both Duncan and Osborne, and command of the unit passed to Lieutenant James B. Robertson. For his exemplary heroism, Osborne was given a posthumous Medal of Honor.

Robertson and Second Lieutenant Clifton B. Cates, a future commandant of the Marine Corps, gathered the remnants of the unit and charged the town. As he approached to within several hundred yards of the hamlet, a bullet ricocheted off Cates’s helmet, knocking him unconscious. A senior NCO pulled a bottle of champagne from his pack and poured it over Cates. The bubbly had the desired effect, and within minutes Cates was up and again leading the assault on Bouresches.

The tiny band of leathernecks streamed into the town and engaged the Germans in house-to-house fighting, driving them from their positions. Accurate rifle and pistol shooting cleared the village, except for the railroad station. Lieutenant William Moore, Sgt. Maj. John Quick, and 10 other volunteers commandeered a truck and made a mad dash to Lucy-le-Bocage for supplies. They returned and ran the gauntlet back to Bouresches, dodging enemy fire all the way. Reinforcements managed to arrive as well, but the fighting in and around the village would continue sporadically for weeks. The small contingent of Marines would not be relieved until June 13, when U.S. Army troops finally broke through.

When the sun set on June 6, the Marines had endured their worst day of fighting since their inception in 1775. In all, they had incurred nearly 1,100 casualties. Despite this, they had secured the flanks and captured Bouresches. All that remained was holding the woods itself—not an easy task, and one that would continue for weeks to come.

Clearing the Southern Edge

Another assault upon the dreaded woods was planned, one that is still steeped in controversy. Major Frederick M. Wise, Jr., commanding the 2nd Battalion, 5th Marines, claimed that he had received Harbord’s go-ahead to set into motion an attack without brigade headquarters meddling in the planning. With the exception of Wise’s memoir, entitled A Marine Tells It to You, which he coauthored with Meigs O. Frost, there are no records indicating such an order was given by Harbord to Wise In his memoir, Wise describes a conversation he claims he had with Harbord: “Wise, the Sixth Marines have made two attacks on the Bois de Belleau,” Harbord reportedly said. “The first one failed. The second made little headway on the southern edge of the woods. You’re on the ground, there. You know the conditions. It’s up to you to clean it up. Go ahead and make your own plans and do the job.” Whether or not Harbord actually said this to Wise is still argued among historians today. Regardless, Wise began formulating an attack and planned to have his men “hit them where they weren’t looking for it.” Wise chose to penetrate the Germans’ rear and interdict their supply lines in the northern part of the woods.

Field orders received from brigade headquarters during the night completely contradicted Wise’s plan and directed his battalion to strike the enemy in the southern sector of the woods. “I knew that piece of paper meant needless death of most of my battalion,” Wise said. Right or wrong made little difference to the riflemen who went over the top on the morning of June 11. A dense mist, coupled with the predawn darkness, concealed their movements for a while, but soon German gunners had zeroed in on the advancing leathernecks. Automatic weapons swept the attacking waves, and the unearthly moans of the dying men filled the air. “We moved forward at a slow pace, keeping perfect lines,” recalled First Lieutenant Samuel C. Cumming, a platoon leader attached to the 51st Company. “Men were mowed down like wheat. A ‘whiz-bang’ [high-explosive shell] hit on my right, and an automatic rifle team which was there a moment ago disappeared, while men on the right and left were armless, legless, or tearing at their faces.”

Although the companies were being massacred by the Maxims, the infantrymen pushed forward. Wise inadvertently sent a message to Harbord that the woods had been captured. Lieutenant William R. Matthews, the battalion intelligence officer, disagreed and went on a personal reconnaissance of the area, evading enemy bullets and shells in the process. He reported to Wise and informed him that his left flank was entirely in the air. Resisting this unwanted information at first, Wise soon realized that his maps, provided by the French, were inaccurate and that Matthews was correct. Nevertheless, by day’s end, the 1st Battalion, 6th Marines had cleared the southern edge of the woods, while the 2nd Battalion, 5th Marines had secured a foothold on the northern part. At the same time, the hitherto unshaken morale of the Germans was breaking. One German soldier later wrote, “We are having very heavy days with death before us hourly. Here we have no hope ever to come out.”

200 Ambulances

Disintegrating morale or not, the Germans were not giving up. On June 14, they unleashed mustard gas, along with a rolling artillery barrage, on the Marines, catching numerous men unprepared. Huge casualties ensued. The 2nd Battalion, 6th Marines was trapped in the open attempting to relieve Wise’s men in the woods. One company had only a dozen riflemen left—the rest were either dead, wounded, or gassed. Two days later, fresh troops from the 7th U.S. Division relieved the exhausted Marines and set out to seize the remainder of Belleau Wood. Unfortunately, the doughboys ran into the same stubborn resistance the leathernecks had been experiencing for the past two weeks.

On June 20, elements of the 1st Battalion, 7th Infantry, were driven back as they tried to eradicate the German machine gun positions. The battalion suffered 63 dead, wounded or missing in its failed attempt. After a stern message from Harbord to the battalion commander, Lt. Col. John P. Adams, ordering him to take his objective, the soldiers attacked the following morning. The second attack was badly disorganized and soon broke down. Disgusted with the unit’s lackluster performance, Harbord sent in Major Maurice Shearer’s 3rd Battalion, 5th Marines as their replacement. (Harbord may have been a bit harsh on the outfit since many of its soldiers had been in the Army for less than six months, and most had no combat experience.)

As the Marine units poured back into their positions, Harbord planned another offensive to clear the woods of the enemy. At 7 pm on June 23, all four companies of the 3rd Battalion, 5th Marines rushed the woods and immediately encountered the now-familiar German Maxims. The terrible sounds of the automatic weapons and exploding grenades and the screams of the wounded saturated the once-tranquil woods. The assault finally ground to a halt, and the American riflemen dug in for the night. There were so many casualties that it required more than 200 ambulances to transport them to field hospitals in the rear.

Wanting desperately to rid the area of Germans, Harbord met with his staff “to make the next assault upon Belleau Wood the last one necessary.” They decided upon an artillery barrage of “maximum intensity,” to commence at 3 am and last until 5 am, to be followed by an assault by the 3rd Battalion, 5th Marines.

“It was Bloody, Nasty Work”

As before, the leathernecks, with foreboding, plunged into the woods with a vengeance. Machine gun emplacements were wiped out. In a letter to his hometown newspaper, the Adirondack Enterprise, after the battle was over, First Lieutenant H.R. Long of the 6th Machine Gun Battalion related his experiences during the fighting: “The forest is very dense and full of rocks with big fissures, crevices, and caves. Germans like Maxims were everywhere among and under the rocks, in places where we could not blast them out with our artillery. Nests survived this rain of high explosives and shrapnel, but the woods were a wreck. It was bloody, nasty work. The Marines just threw away their lives—they couldn’t be held back.”

As the Marines’ momentum increased, it became evident that the German opposition was rapidly collapsing. Realizing this, Shearer shot off a dispatch that read: “We have taken practically all of the woods but do need help to clean it up and hold it. Do we get it?” Shearer got his wish, and the 3rd Battalion, 6th Marines shifted to the north to link up with his battalion and prevent any German counterattacks during the night. A platoon from the 2nd Battalion, 5th Marines also shored up Shearer’s defenses near the depleted 16th Company. Throughout the night there were isolated clashes, but the main enemy resistance had been broken. Hundreds of Germans, sensing that the end was near, threw down their weapons and were taken prisoner by the Marines.

On the morning of June 26, after repulsing a few half-hearted German thrusts at their lines, the Marines finally pushed them from the area. For nearly a month, the leathernecks had fought a tenacious enemy and prevailed. Shearer forwarded the long-awaited message that Harbord had wanted to hear for so long: “Woods now entirely U.S. Marine Corps.” The cost to capture Belleau Wood was horrific. Dead, wounded, and missing totaled 9,777; of that, the Marines suffered 4,298 casualties. No accurate count of German fatalities was ever made—no doubt it was considerably higher—but some 1,600 Germans were taken prisoner.

Devil Dogs

Ecstatic that their capital had been saved from the ravishing Huns, the French high command lauded the Marines with numerous awards and accolades. Belleau Wood itself was given the sobriquet Bois de la Brigade de Marine, or “Wood of the Marine Brigade.” The term Teufel Hunden, which loosely translates as “devil dogs,” was supposedly given to the Marines by the German troops defending the woods. Many historians have doubted that the enemy actually gave the Marines that nickname, but, true or not, the leathernecks seized on it and used it profusely in their public relations efforts to entice new recruits.

Five years later, a monument was dedicated to the fallen at the battle site. General Harbord spoke at the event. “Now and then, a veteran will come here to live again the brave days of that distant June,” he said. “Here will be raised the altars of patriotism; here will be renewed the vows of sacrifice and consecration to country. Hither will come our countrymen in hours of depression, and even of failure, and take new courage from this shrine of great deeds.”

Grandfather fought there. We’ll done.