By Frank James Rottman

After his disastrous invasion of Russia in 1812, French emperor Napoleon Bonaparte desperately needed to reassert his military dominance over Europe. His hold on France depended entirely on his success on the battlefield. As he would later tell Austrian peace envoy Prince Clemens von Metternich, “Your sovereigns born on the throne can let themselves be beaten twenty times and still return to their capitals. My domination will not survive the day when I cease to be strong and therefore feared.” Half a million men had fallen in the past six years to reaffirm Napoleon’s hold on power, and yet by the end of the year the emperor’s much-vaunted Grande Armée was virtually back where it had started when the emperor first seized control of his country’s destiny in 1799 and made all of Europe tremble at his name.

Reconstructing the Grande Armée

In the immediate aftermath of the Russian campaign, Napoleon almost wistfully told Marshal Louis Alexandre Berthier, his chief-of-staff, “Come, Berthier, come my old friend, let us fight the campaign of Italy all over again.” Napoleon was eager to return to the offensive quickly, before the newly allied forces of Russia and Prussia could concentrate their armies in Germany and freeze the French Army into place in a purely defensive position. But before Napoleon could begin a new campaign, a number of urgent questions remained unanswered. Could the master of Europe recoup from his Russian disaster? Would his young, inexperienced conscripts fill the huge void left by the death and destruction of 400,000 crack troops in the Grande Armée? Would his cavalry, now only 7,500 strong, still be able to act efficiently as his eyes and ears for the upcoming campaign? Napoleon pondered these questions obsessively as he made his way toward the city of Leipzig, Germany, in the spring of 1813.

The army that Napoleon brought to the plains of Saxony that spring—outwardly, at least—was not unlike his earlier armies. Morale was high, marching and maneuvering were quick, and individual courage was not lacking. However, the effects of the previous year’s terrible campaign in Russia could not be easily erased with additional levies of untried men. The indomitable French infantry, “the sinew of an army,” was filled with brave, young, but only half-trained conscripts. Neither the surviving officers nor the NCOs had the requisite time or experience of their own to thoroughly train the new men. This lack of experience would hamper Napoleon throughout the ensuing campaign.

“France was One Vast Workshop”

The artillery corps, always Napoleon’s first love, was quickly supplied with new cannon of all caliber and teams of horses to make up for the grievous losses of some 1,200 pieces in Russia. Because of a shortage of gunpowder, new mills were built and armorers were goaded to increase production. “France was one vast workshop,” cavalry general Armand de Caulaincourt observed. “The entire French nation overlooked his reverses and vied with one another in displaying zeal and devotion. It was as glorious an example of the French character as it was a personal triumph for the Emperor, who with amazing energy directed all the resources of which his genius was capable into organizing and guiding the great national endeavor. Things seemed to come into existence as if by magic.”

To alleviate the shortage of artillerists, National Guardsmen and green conscripts were made into gunners on the march. Although the artillery had first pick of all horses throughout the empire, they faced the same shortage as the cavalry. Complicating matters was the fact that the new draft horses had to be carefully matched in teams and trained to move heavy loads at a quick, sustained speed. Despite the shortage and training required, Napoleon somehow managed to provide the artillery with an adequate supply of horses. His superhuman rebuilding efforts were successful, and the emperor believed that the reconstituted artillery would compensate for the shortage of cavalry in the upcoming operations.

After the Russian debacle, the cavalry was in desperate shape. One example of the level of cavalry losses suffered was the experience of the 11th Hussars, which had brought 1,133 men and horses into Russia in the summer of 1812 and escaped six months later with a mere 10 officers and 79 enlisted men. These prolific losses could not be easily replaced, and Napoleon needed more time to gather sufficient numbers of healthy horses and troopers—time he would not be given. With no other choice, he collected and attempted to train the resources he had available. The remounts were few in number and poor in quality. The officers and men were no comparison to the Allied veterans they would soon be fighting. Many French conscripts in the cuirassiers, the French heavy cavalry, were too slight to carry their large swords and heavy helmets. Others were preoccupied with learning the proper way to ride and fight man-to-man in combat, and thus could not spend precious time training for mass maneuvers. Experienced light horsemen, the chasseurs-a-cheval, were also in short supply. Without his light cavalry, Napoleon would be hard pressed for accurate information about his enemies’ dispositions.

Purity of the elite Imperial Guard

The Imperial Guard, Napoleon’s veteran reserve, had also suffered greatly in Russia. One hard-bitten survivor, Sergeant A.J.B. Bourgogne, told the story of a fellow Guardsman who inquired as to the whereabouts of the Dutch grenadiers. Bourgogne responded, “You didn’t see it? That big sledge that overtook you contained the entire Dutch regiment.” There were seven men left. After the Russian campaign, the Old Guard was a mere skeleton of its original 30,000-member elite force. After removing the sick and wounded, the Guard consisted of 1,065 infantry, 663 cavalry, 265 artillerymen, and 26 engineers. Knowing that he would need their fighting ability and élan to steady his green conscripts in line and possibly snatch victory from defeat, Napoleon set about rebuilding the Guard as quickly as he could. He refitted the ranks with veteran soldiers from Spain and France, used seamen to reinforce his Guard artillery, and scrounged all over France for mounts for his Guard cavalry regiments. Every department in the empire was directed to supply men and equipment for the Guards, including 5,000 retired Municipal Guards who were recalled to the colors. At the same time, the entire Class of 1814 from the nation’s various military academies was called into service a year early.

Ever watchful of his beloved Guard, the emperor continued to insist that the criteria for joining the Guard must remain stringent. In March 1813, Napoleon wrote, “A non-commissioned officer may not be admitted into the Old Guard until he has served twelve years and fought in several campaigns. If nominations contrary to this rule are made they shall be presented for confirmation to the emperor before taking effect.” Clearly, Napoleon knew that the coming campaign’s success would rely upon his beloved Guard’s fighting prowess. The Guard would either help lead the French forces to victory or, as in Russia, safeguard their retreat.

March on Leipzig

With his young and inexperienced army, Napoleon would attempt to check the Allied advance into the Confederation of the Rhine and possibly regain his near-hypnotic spell over the Russian Czar Alexander I. Napoleon’s master strategy was to capture Berlin and give Prussia reason to doubt its decision to declare war on March 13. Napoleon’s attention in the north did not mean that he would forget the south. In fact, he hoped to gain a quick victory in the south in order to bloody his new recruits and build up morale, while giving Austria pause to reconsider its newly antagonistic relationship with France. He hoped that quick success over the Allies in the south would keep the disaffected members of his own army under wraps.

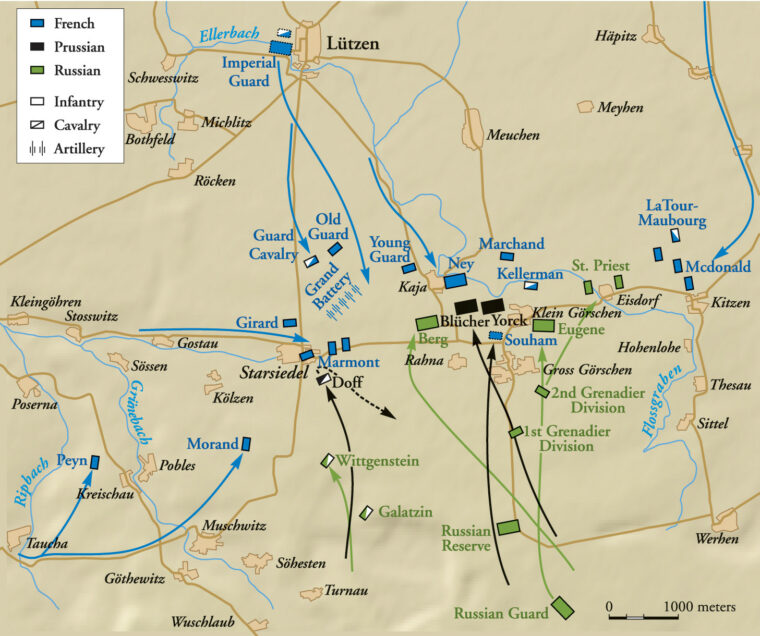

Napoleon believed the Allies would begin a major spring offensive with an attack on Leipzig. Therefore, on May 1, he ordered his forces to advance onto the Saxony plain. The French military machine came toward Leipzig from two directions. The Army of the Elbe, with an overall strength of 30,000 men under the direction of Prince Eugene Beauharnais, Napoleon’s stepson, moved toward Leipzig from the north. The Army of the Main, numbering 115,000 under Napoleon’s direct command, came up from the south toward Weissenfels. As Napoleon moved forward, he gave Marshal Michel Ney’s III Corps the responsibility for securing his right flank by occupying the historic village of Lutzen, site of a major victory by Protestant forces over their Catholic adversaries in the Thirty Years’ War 180 years earlier. Ney was also tasked with taking and holding the nearby villages of Kaja, Rahna, Gross Görschen, and Klein Görschen. This action would safeguard the French right, while allowing General Jacques Lauriston and Marshal Jacques Macdonald to advance on Leipzig unmolested.

Lutzen: Focal Point of the Allied Advance

In the early hours of May 2, Napoleon continued to expect a confrontation with the Allies at Leipzig or just south of the city. However, he became uncomfortably aware of the precarious position of his supply line and entertained the possibility of a strong Allied advance from the direction of Zwenkau that would cut his Army of the Main in two. To guard against this happening, Napoleon warned Ney that if an Allied attack came from the direction of Zwenkau, his III Corps would have to take a defensive posture and pin down the enemy near Lutzen while the Army of the Elbe moved around to attack the Allied left. At 4 am, Napoleon, still unaware of the Allies’ intentions, issued a written order to Ney to send out two strong reconnaissance forces, one toward Zwenkau and the other toward Pegau.

For some reason, Ney failed to implement the order. Instead, he sent two of his five divisions out toward Kaja and Starsiedel, but they made no attempt to continue forward into Zwenkau and even failed to fortify their positions. Instead, the men were allowed to forage for their lunch. One possible explanation for Ney’s dereliction may be that because he lacked sufficient numbers of light cavalry, he was unaware that the Allies were present in any great force.

At about the same time, the Allied commander, Count Ludwig Wittgenstein, sent out a reconnaissance force to scout the French positions near Lutzen. Wittgenstein could hardly believe his ears when he heard their report. The main body of French troops was moving toward Leipzig on the Weissenfels-Lutzen highway. A small detachment of French soldiers was present near Kaja, and stronger detachments were near Teuchern. Wittgenstein surmised, a little wonderingly, that he had surprised the French. The French, without a sufficient cavalry arm, had no idea that the Allies were concentrated near Kaja. For the first time in his experience, Wittgenstein had managed to seize both the battlefield initiative and a superior concentration of forces over Napoleon.

The Allied commander quickly formulated a plan of attack. He would make a lightning strike at Lutzen and cut the Weissenfels-Lutzen highway. The result would be a complete split of the French forces. Wittgenstein envisioned the entire operation taking six hours, commencing at 1 am and concluding at 7 am. Meanwhile, he ordered General Friedrich Kleist to hold the Allied right at Leipzig while General Mikhail Miloradovitch moved toward Zeitz to protect the Allied left. The rest of Wittgenstein’s 71,000-strong forces would quick-march to Gross Görschen. From there, Wittgenstein planned to capture Kaja and position his artillery to cut the highway, thus forcing the French to retreat toward the River Elster or else be cut in two.

Driving the French Back

Unfortunately for Wittgenstein, his careful timetable quickly started to unravel. Beginning their march in near-total darkness, his lead formations did not reach Gross Gröschen until 11 am. However, although their timing was off, his forces still held the tactical advantage of surprise and superior numbers. Confident of complete victory and wishing to make up for lost time, Wittgenstein ordered Marshal Gebhard Blücher’s cavalry to attack the French force, believed to be 2,000 men, near Gross Gröschen. The Prussians soon received a rude surprise when they found themselves facing two complete French divisions instead of 2,000 hapless troopers. Likewise, the French received a comparable shock when a large Prussian force materialized in front of them.

Both sides quickly took action. Blücher called for artillery, while the French commander, General Joseph Souham, following Napoleon’s precept that lost territory could be recovered but time never could be, took advantage of the Allied pause by occupying Gross Görschen. On his immediate right, General J.B. Girard consolidated his forces around the village of Starsiedel. Because of the Allies’ poor reconnaissance and subsequent delay, the French found themselves in defensible positions. Both Souham and Girard felt confident that they could hold out long enough for General Auguste Frederic de Marmont VI’s Corps to come to their aid.

After the arrival of his artillery, Blücher unleashed a devastating cannonade, consisting of 45 guns, against Souham’s position at Gross Görschen. After sustaining an estimated 4,000 rounds of artillery, the French were hard pressed to hold the village and moved behind Gross Görschen. The Prussians took the village and, with two Russian columns, attacked Kaja. At midday, the French retired behind Kaja to hold fast until help arrived. Unfortunately for Souham’s forces, helping the men of the III Corps was not yet part of Napoleon’s plans.

As a desperate struggle was taking place at Gross Görschen, Napoleon, with Ney at his side, followed the trouncing of Kleist by Lauriston’s V Corps at Leipzig. Napoleon still believed that the Allies were concentrated there. Macdonald recalled, “He gave me orders to support him [Lauriston] if necessary, but at that moment he received intelligence that the allies who had debauched from Pegau were advancing towards us. The Emperor would not believe it, because he was firmly convinced that their main force was at Leipzig.” However, after both Napoleon and Ney heard the increasing cannon fire to the southwest, he ordered Ney to return to his command at Lutzen with all possible speed. At the same time, Napoleon began to formulate a new plan to meet the growing threat to his right.

“We have no cavalry and must do it with infantry, as in Egypt,” Napoleon told subordinates. Orders were sent out for the III Corps to hold all its present positions at all costs. The Imperial Guard would wait in reserve. Marmont’s VI Corps was to move up to Ney’s right around Starsiedel, while General Henri Bertrand’s IV Corps moved west from Tauchau to threaten the Russian left. Meanwhile, the Russian right would be assailed by Macdonald’s XI Corps and two divisions from Lauriston’s V Corps, which would swing southward toward Eisdorf. Napoleon felt his personal presence on the field might be necessary and quickly followed Ney toward the fighting.

A Fierce Fight for Lutzen

The events between 11 am and 1 pm showed just how well the Allies had surprised the French. Of all Lutzen’s outlying villages, only parts of Kaja remained in French hands. The Allies were close to pushing the French from their defensive positions and creating a wedge between the divisions of Souham and Girard. In fact, Souham was being driven back by a heavy concentration of artillery fire. Fortunately for the French, Girard held his position. Ney arrived at Lutzen in time to gather his three remaining divisions and rush them forward to stop Souham’s retreat. He ordered an aide to “go tell the Emperor that it really is a battle and a battle such as he has never seen before.” While this was being done, Ney joined the battle with his usual courage and élan.

The fighting was fierce—both sides realized that Lutzen was the key to victory. If the Allies succeeded, they would split the French in half. If the French held, they might succeed in enveloping the Allies. Ney, covered by dust from his ride, soon lost his horse to a cannonball and was wounded in the leg by an enemy musket, but stubbornly remained at the center of the conflict. Girard fared no better. While leading his division forward, he was wounded twice. Gathering his remaining strength, he called out a ringing challenge: “It is here that every brave Frenchman must conquer or die!” Hit by a third bullet, Girard reluctantly relinquished command.

The French and Prussians continued to pound away at each other. Decimated villages were won and lost within minutes by both sides. The French were running out of ammunition for their cannon and muskets. Along with Ney and Girard, Souham and his chief of staff had been wounded. French morale, however, remained intact. The Guard artillery performed prodigious tasks of marksmanship, and Ney’s small cavalry brigade, although outnumbered, continued to protect the rear from the dreaded Cossacks. The French still held Kaja, the largest and closest village to Lutzen. Meanwhile, the Allies suffered an incalculable loss with the mortal wounding of the Prussian chief-of-staff, Gerhard von Scharnhorst, the developer of the modern general staff system.

Even with the death of Scharnhorst, the Allies felt confident of victory. They had surprised the French and held them on the defensive for most of the day. However, to claim a complete victory they would have to drive the French out of Kaja and Lutzen before Napoleon managed to consolidate his forces. They renewed their attacks with a determination bordering on desperation. Prussian cavalry and Guards made a coordinated strike toward Kaja. Their attack was overwhelming. In one brief lightning strike, they captured Klein Görschen and Rahna and almost reached the key village of Kaja. They believed the battle was as good as won.

“Vive l’Empereur!”

French confidence quickly dissipated. Even with Marmont’s VI Corps joining Ney’s right, they believed the battle to be lost. Cries of “Sauve qui peut! [Every man for himself]” were heard as the young conscripts threw down their arms. The French army that Napoleon had forged from nothing was beginning to crack under the intense Allied advance. Veteran troops might have been able to withstand the intense three-hour fight, but the inexperienced conscripts were wavering quickly. Unlike 1812, this defeat could not be attributed to the force of nature or unreliable allies. The French were about to be defeated fairly and squarely by the Prussian and Russian armies. All was lost—or was it? Word began to pass from man to man: the Emperor had arrived. Excited shouts of “Vive l’Empereur!” filled the air.

At 2:30 pm, Napoleon personally joined the fray. French morale rose accordingly. In a moment, the customary French élan returned. Napoleon’s first order was to rally the III Corps conscripts who were in full flight. He commanded the Light Horse of the Old Guard to “bar their passage between our squadrons.” Meanwhile, Napoleon rode among his troops instilling his confidence in both veterans and recruits. “This,” recalled Marmont, “was undoubtedly the day, of his whole career, on which Napoleon incurred the greatest personal danger on the field of battle. He exposed himself constantly; leading the defeated men of III Corps back to the charge.” The Saxon translator E. d’Odeleben recalled, “Hardly a wounded man passed before Bonaparte without saluting him with the accustomed vivat. Even those who had lost a limb, who would in a few hours be the prey of death, rendered him this homage.”

During the afternoon, both armies fought fiercely, but neither side could claim complete victory. With each passing hour, Napoleon’s plan of envelopment was taking shape. Macdonald came into contact with the Allied right and made his presence felt with devastating fire on the enemy infantry and cavalry in that sector. With Miloradovitch’s Russians coming up from Zeitz, Bertrand deliberately slowed his movement toward Marmont until 3 pm in order to ensnarl the Russians in the flank. Feeling that Miloradovitch’s forces were sufficiently exposed, at 4:30 pm Bertrand’s corps began to assemble on Marmont’s right. Napoleon’s enveloping movement was beginning to materialize.

Victory from the Jaws of Defeat

Faced with a growing menace on both his right and left flanks, Wittgenstein needed a steady flow of additional men to hold his present position near the village of Kaja. What reserves he had arrived at a trickle because Czar Alexander, believing that the Allies were victorious and wishing to emulate Napoleon’s practice of sending his Imperial Guard forward for the coup de grace, held back Russian general A.P. Tormassov’s Guards. In spite of the czar’s personal intervention, by 4 pm Wittgenstein had a sufficient number of reserves on hand and rushed them forward to Kaja. The Prussians were making the supreme effort to breech Napoleon’s center. The emperor wondered if his worn-out, severely punished III Corps and untested Imperial Guard would hold their positions or falter. “You will defend these batteries,” Napoleon told the veterans, “and if the enemy attacks you shall give a good account of yourselves.”

As if to underline the emperor’s words, Allied grapeshot immediately smashed into two files of grenadiers. The Guard flinched. The cannonade increased in quickness and accuracy. A derisive Napoleon wondered aloud, “What does the Guard duck?” A bomb fell in front of the first division and destroyed 30 muskets. This time, not one man winced. Satisfied that the Guard was holding fast, Napoleon ordered the Young Guard and remnants of III Corps to counterattack.

Although very nearly successful, Wittgenstein’s all-out effort used up his reserves and proved to be his last serious threat on Napoleon’s center. By 6 pm, Macdonald took Eisdorf on Ney’s left, and Bertrand was fully deployed on Marmont’s right. Napoleon ordered Marshal Adolphe Mortier and his 10,000 Young Guardsmen to assault the enemy forces remaining in and near Kaja. At the same time, he directed General Auguste Drouot to concentrate all available artillery southwest of Kaja to support the Guard’s advance. Finally, Napoleon moved six battalions of Old Guard, Guard Cavalry, and remnants of III Corps behind the artillery to support the Young Guard’s breakthrough. Ever the gambler, Napoleon was sure that the odds were now on his side and that the time was right for a final thrust.

“La Garde au Feu!” Napoleon barked, ordering Mortier to lead 16 battalions of the Young Guard into their first major battle. At first, the four attack columns moved forward at a slow, hesitant pace, with no look of pride or conquest in their eyes. Sensing their fear, the man who had cultivated their loyalty, obedience, and devotion like a father would his sons proclaimed, “Know that our fate is decided. If we are destined to die, perish we must. En Avant!” The Young Guard’s martial fire began to burn. They would continue the Imperial Guards’ tradition of loyalty, obedience, and devotion to emperor—or die trying. In short order, the villages of Rahna, Kelin, and Gross Görshchen were recaptured by the Young Guard, who suffered 1,069 casualties. Napoleon was so impressed by their fighting élan that he would later write with simple approval, “The Young Guard has fulfilled our expectations.”

The Allied line began to crack then crumble. The men who had fought so hard and long and who had almost tasted victory were now pushed back to the Elster. They only avoided a complete rout because of the lack of French cavalry. Hostilities ended at 9 pm with a Prussian cavalry counterattack against Marmont’s chasing infantry.

“I am Once More Master of Europe”

Napoleon boasted after the Battle of Lutzen, “I am once more master of Europe.” However, his new mastery came at a cost he could ill afford. French losses in killed and wounded totaled at least 20,000. The Allies’ losses were between 11,500 and 20,000. Wittgenstein had caught the vaunted Napoleon by surprise and until late afternoon was in a position to claim victory. Even when enclosed by a slowly developing pincer movement, the Allies managed to retreat in a disciplined, professional manner. Napoleon bitterly commented, “These animals have learned something.”

Conversely, the Allies were confronted with the sobering fact that the French Army was not a paper lion and that Napoleon’s battlefield faculties were as keen as ever. Although short of experienced soldiers and crippled by a lack of cavalry, Napoleon had won an improbable but undeniable victory. “In my young soldiers,” he said, “I found all the valor of my old companion in arms. During the twenty years I have commanded French troops I have never witnessed such bravery and devotion.” Napoleon’s faith in his army, combined with his military genius, would mean another full year of war in Europe. As he had demonstrated convincingly at Lutzen, the old emperor still had a few more tricks up his sleeve.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments