By John Wukovits

In warfare, desperate times call for desperate measures, and in the fall of 1944 the empire of Japan found itself in precisely that predicament. Running wild through the vast South Pacific in the war’s earliest months, Japanese military forces had since enjoyed few successes while absorbing critical defeats. The American military machine, temporarily grounded after Pearl Harbor, had returned with a vengeance.

Fueled by grim determination, mountains of reinforcements, and thousands of ships, tanks, and aircraft, the U.S. registered a series of advances that brought its military to the inner reaches of the Japanese empire. At the same time, American submarines savaged Japan’s merchant fleet and drastically reduced the crucial flow of oil.

With the enemy poised to assault the Home Islands, Japanese military strategists concocted four different responses called the SHO Plans. Depending where the United States chose to advance, the Japanese would focus their efforts in either the Philippines, the island of Formosa to the west, the Kurile Islands to Japan’s northeast, or the Japanese Home Island of Honshu.

When it seemed obvious that the Americans had chosen the Philippines as their next objective, Japan enacted its SHO-1 plan for the defense of these islands. An elaborate plan in which succcess depended on the precise movements and coordination of four different naval forces, SHO-1 hoped to employ one force to lure away from Leyte Gulf the potent aircraft carriers that stood guard over the American invasion forces, while three other Japanese units slipped in to attack the vulnerable landing forces.

Risking the Remaining Japanese Navy’s Strength

A Northern Force, commanded by Vice Admiral Jisaburo Ozawa, would steam down to the Philippines from the north in an effort to lure away the American carriers, under the command of American Admiral William F. Halsey. At the same time, Vice Admiral Takeo Kurita would lead his Center Force through the San Bernardino Strait and attack American units in Leyte Gulf from the north, while his cohort, Vice Admiral Shoji Nishimura, supported by Vice Admiral Kiyohide Shima, led the third and fourth naval units against the Americans from the south.

The plan risked almost the entire remaining strength of the Japanese Navy. Should it fail, little would remain to halt the growing American naval power. This worried senior officers of the Japanese Imperial Army, who feared that a defeat would further reduce the availability of overseas products and drastically limit their ability to defend the Home Islands. The Navy, however, wanted to implement the plan before American factories produced even more ships and aircraft.

The Japanese marshaled every ship they could to improve their chances of success. Admiral Ozawa commanded six aircraft carriers in his decoy force–Ise, Hyuga, Zuikaku, Zuiho, Chitose, and Chiyoda–but since they were designed to grab Halsey’s attention and were expected to be destroyed by his more powerful surface units, they carried only 116 aircraft. In addition, three light cruisers and eight destroyers screened Ozawa’s force. To the south, Nishimura’s two battleships, one heavy cruiser, and four destroyers would join with Shima’s three cruisers and four destroyers in an advance through Surigao Strait for an attack from that quarter.

The final force, under Kurita, packed the most powerful punch. Anchored by the two most lethal battleships in the world, Yamato and Musashi, a total of five battleships, 10 heavy cruisers, two light cruisers, and 13 destroyers would barrel through San Bernardino Strait to the north of Leyte Gulf. They would hopefully emerge to an unprotected, open sea and pounce on the Americans from the north, while Shima and Nishimura steamed in from the south. The surprise assault would then reduce the American landing operations on the island of Leyte. If successful, the plan would safeguard the Philippines, delay the American advance by weeks if not months, and keep the enemy away from the Home Islands.

However, one crucial aspect of the plan unraveled before the Japanese Navy sortied for the attack. Kurita expected air support from Japanese aircraft based in the Philippines, but American attacks on both Filipino airfields and a massive raid by Halsey against Formosa destroyed many of the aircraft earmarked to assist Kurita. Fewer than 100 aircraft remained in the Philippines, far less than needed to parry the expected American aerial assaults against Kurita as he wound his way closer to the San Bernardino Strait.

In a lapse that sometimes happens in war, Kurita never received word that his air support had been so badly mauled. Without realizing it, he faced a taxing voyage across the wide Sibuyan Sea off the Philippines’ western approaches with no air cover. Should the enemy appear overhead, Kurita would be caught in the unenviable position of battling aircraft with nothing but the guns mounted on his ships.

“I Expected Complete Destruction of My Fleet”

The immense operation started on the morning of October 18, 1944, when the chief of the Japanese Naval General Staff, Admiral Soemu Toyoda, sent out the “Execute” command to begin SHO-1. That same day, Kurita led his flotilla out of Lingga Roads near Singapore to Brunei Bay in Borneo. On October 22, after refueling had been completed, Kurita took his ships to sea and headed northwest for the Palawan Passage. From there, Kurita would steam across the Sibuyan Sea, rush through the San Bernardino Strait, and attack the Americans.

On the afternoon of October 22, Admiral Nishimura departed his anchorage near Singapore and headed for the Sulu Sea, while Shima steamed from the north for a joint assault through Surigao Strait to the south of Leyte Gulf.

The final element, led by Admiral Ozawa, left Kure in the Home Islands on October 20, skirted outside the range of American search planes on Saipan to avoid early detection, and steered toward the northern portions of the Philippine Islands. Ozawa, serving as the sacrificial victim, saw little hope of returning. “I expected complete destruction of my fleet,” he later explained, “but if Kurita’s mission was carried out, that was all I wished.” Thus, a vast portion of the success of SHO-1 depended upon Kurita achieving his mission. It did not take long before doubts on this point surfaced.

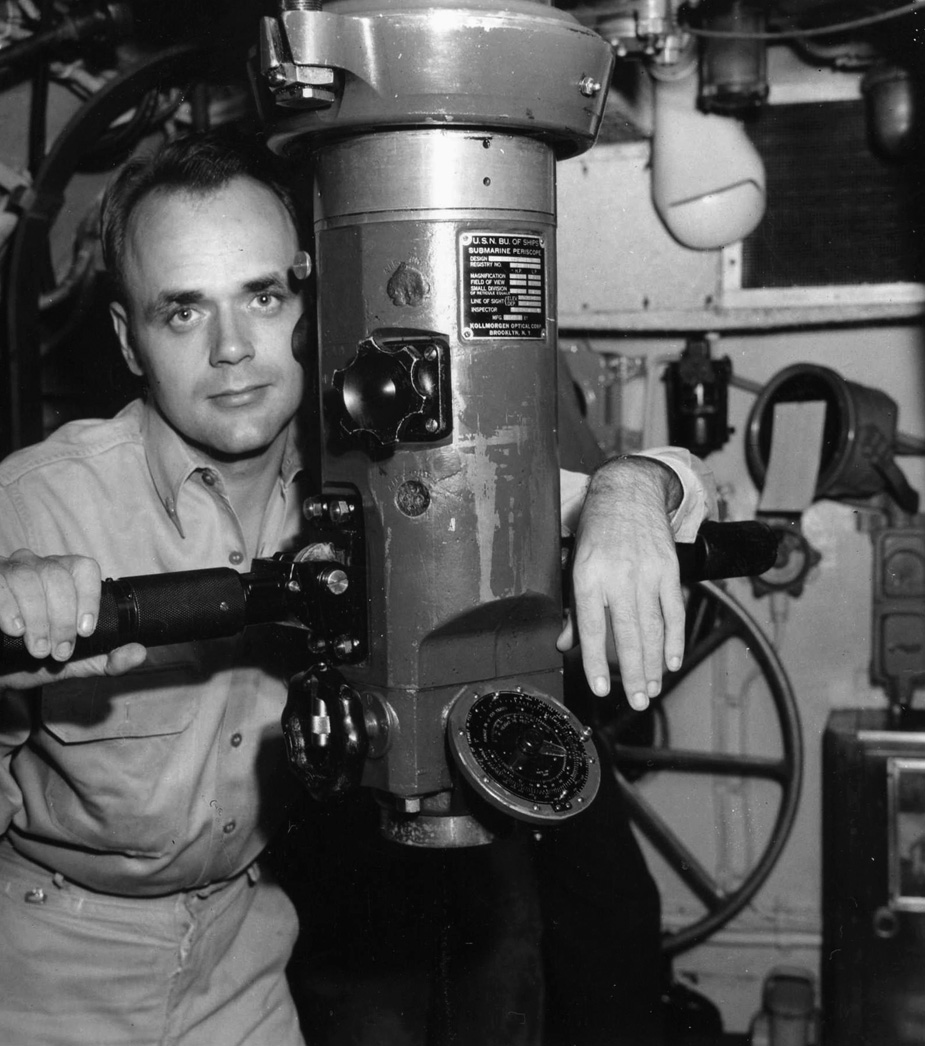

Some distance out at sea, the crews of the U.S. submarines Darter and Dace prepared to head back to Australia. Short of food and weary from the constant state of readiness required in their lengthy mission, the submariners counted the days until October 23, when they could finally set course for Australia and much needed rest. “Our thoughts were more on that island, on fresh food, mail from home, and the two weeks of shore leave than on the war,” Dace’s executive officer, Lt. Cmdr. R.C. Benitez later wrote. Only one more day and they could focus on fun and sleep rather than responsibility and battle.

Commmander David H. McClintock of Darter and Commander Bladen D. Claggett of Dace issued orders that would send their boats away from the war zone in a matter of hours. On October 22, as was the custom, the boats surfaced at dusk, and calm seas reflected the state of mind aboard the pair of submarines.

That changed shortly after midnight on October 23, when Darter spotted a group of ships steaming into the southern entrance to the Palawan Passage about 350 miles west of Leyte Gulf. McClintock ordered the two boats to close on the targets, which required McClintock and Claggett to head at top speed through an area nicknamed the “Dangerous Ground,” a threatening stretch of water containing numerous reefs, shoals, and rocks. If they hoped to reach an advantageous intercept point, however, the submarines had to risk the treacherous waters.

When McClintock and Claggett moved in on the enemy force, they noticed a surprising fact. The enemy commander had failed to post any destroyers ahead of his formation to guard against a head-on attack. He churned forward in two sections, each containing primary columns of heavy cruisers and battleships escorted on the flanks by light cruisers and destroyers. While this shielded the Japanese flanks from a submarine attack, the formation exposed the enemy commander to a frontal torpedo assault.

The Chaos Left the Japanese Without Their Leader

More astonishingly, instead of destroyers leading the columns, Japanese heavy and light cruisers led the way. The light cruiser Noshiro stood first in one column, while the heavy cruisers Myoko and Atago steamed ahead of the other ships in two adjoining columns. With this formation, the Japanese commander almost invited an attack on his more valuable cruisers instead of the more expendable destroyers. The sinking of the Atago, which served as Kurita’s flagship, would toss the formation into even more chaos during an encounter, leaving the Japanese without their leader.

McClintock and Claggett also thought it a bit unusual that a Japanese commander would purposely steam through the narrow Palawan Passage when he had other options available. Kurita, however, selected this path despite the threat of reefs and American submarines because it placed him outside the search range of American planes operating out of the Philippines. In addition, this shorter route would negate any need to refuel at sea, a time-consuming operation.

McClintock and Claggett reached their intercept positions shortly after 5:00 am. The Japanese would first encounter the Darter, waiting on the northwest sector of the Japanese fleet. Claggett halted about five miles northeast of Darter, ready to launch his torpedoes in case the Japanese veered to the starboard to avoid McClintock.

McClintock fired the initial shots of what became known as the Battle of Leyte Gulf at 5:32 am when he unleashed six torpedoes from his bow tubes at Kurita’s flagship, Atago, from less than 1,000 yards. As soon as the sixth fish left its tube, McClintock swung his stern tubes to bear and fired four more torpedoes, this time at the second ship in line, the heavy cruiser Takao.

Explosions Erupted Like Fireworks

Five eruptions quickly indicated to McClintock that most of his first six fish struck their mark. From farther away, Claggett watched the show unfold through his periscope. When the torpedoes exploded, he shouted to those nearby, “It looks like the Fourth of July out there! One is burning. The Japs are milling and firing all over the place. What a show! What a show!”

McClintock’s torpedoes reaped enormous dividends. Within a half-hour, Kurita’s flagship disappeared beneath the waves, leaving a frustrated commander floating in the waters. Takao sustained such heavy damage that she had to reverse course and head back to Brunei. The Battle of Leyte Gulf was only moments old and already Kurita had lost two heavy cruisers.

Claggett now moved in. With Kurita in the water, Rear Admiral Matome Ugaki took temporary command. He increased the formation’s speed to quickly outdistance his submerged foe, but this only placed him in Claggett’s crosshairs. Four torpedoes sped from the Dace directly into the heavy cruiser Maya, which sank under tremendous explosions. A wet and exhausted Kurita was just being taken aboard the destroyer Kishinami when he saw a series of flashes in the distance. He turned to view the death throes of yet another of his ships.

The eruptions created such a loud noise that the Americans aboard the Dace feared the worst for themselves. “On our way down, a crackling noise that started very faintly but which rapidly reached staggering proportions soon enveloped us,” wrote Lt. Cmdr. R.C. Benitez. “It was akin to the noise made by cellophane when it is crumpled. Those of us experienced in submarine warfare knew that a ship was breaking up, but the noise was so close, so loud, so gruesome that we came to believe that it was not the Jap but the Dace that was doomed.”

Some crew members worried that their boat was breaking up, while others entertained the depressing specter that a ship brought down by their torpedoes might plunge directly on top of the submarine and either crush it or pin it to the sea floor. The diving officer, with concern etching his face, said to Claggett, “We better get the hell out of here!”

As the Dace sped away, the boat shook from Japanese depth charges. For a few hours, the men endured a series of attacks that rocked the Dace, shattered lightbulbs, tossed out the contents of lockers, and dumped tools onto the floor. “The Japs were very mad and we were very scared,” admitted Benitez, but the Japanese departed without striking the boat. Later in the day, Claggett, after waiting a safe time, surfaced to find an empty sea.

The Japanese had steamed out of view, but the dangerous reefs and shoals remained. A few minutes into October 24, Dace received a message from Darter stating that the boat had run aground on one of the numerous reefs. When the Dace moved in for a close look, Claggett could clearly see Darter’s propellers out of the water. He had no choice but to take the Darter’s crew aboard his boat, then torpedo the hapless submarine so it did not fall into enemy hands. Crewmen placed demolition charges aboard the Darter, but all failed to properly ignite. Claggett then fired four torpedoes, but as the Darter stood too high out of the water, each missile exploded harmlessly against the reef.

Claggett’s Worst Fear Materialized

Claggett now turned to his final option, using his deck gun to sink the submarine. He hesitated to do this as it required the full deck gun crew of 25 men to be on deck. Should an enemy aircraft appear in daylight while they were attempting to destroy Darter, it would force Claggett into a speedy dive, and some of those men might not make it to the tower hatch in time. He knew he had to take that risk.

Dace’s gun sprayed the Darter without inflicting much damage. After demolition charges, four torpedoes, and the deck gun had failed to sink the Darter, some of the crew joked that maybe they would be safer aboard the beached boat.

They did not enjoy their laughter for long, as Claggett’s worst fear materialized. A Japanese plane veered toward them in an obvious bombing run around 6 am. The 25 crewmen rushed for the 25-inch tower hatch in a mad scramble as Claggett readied his boat for a hasty dive. Some men slid down the hatch, some fell head first, and others were shoved down by anxious mates behind, but all safely entered the boat before the waters covered her.

Fortunately, they did not have to worry, as the Japanese pilot targeted the Darter. From the air, the Darter apparently looked as if she still floated on the surface rather than being stuck on a reef, and with the Dace already submerging, the Japanese pilot descended on Darter as the better target. “That dumb ass of a Japanese pilot!” yelled one American sailor, “He made his drop on Darter.” The relieved crews of both boats, now packed into the tight confines of Dace, hoped the enemy airman could do what their own weapons could not, destroy Darter, but his bomb missed its mark.

Claggett remained near Darter until night, when he maneuvered closer to make another attempt to sink the boat. As he prepared to launch more torpedoes, the ping of underwater echo-ranging indicated the presence of another submarine. Since no other American boats prowled these waters, Claggett decided to abandon Darter and move the two crews out of harm’s way. He set a course for Australia and left the Palawan Passage.

The action in the Palawan Passage handed the United States a victory in the first phase of the Battle of Leyte Gulf. At the cost of one submarine, the abandoned Darter, U.S. forces sank two cruisers, damaged one, and removed two destroyers that were detached to escort the Takao to Brunei. Before the Japanese commander had engaged enemy surface forces, he saw his flotilla depleted by five ships. More importantly, his presence in the Palawan Passage had been relayed to American naval commanders, which meant that an air attack loomed, followed by a probable advance against an American Navy arrayed to halt its progress.

This realization would test the mettle of any commander, but since Kurita had just emerged from the harrowing ordeal of having to abandon his sinking flagship and jump into the sea to save his life, the attack carried a stronger psychological effect. If this could happen so soon in his journey to the Philippines, what waited for him as he drew closer to the enemy? To make matters worse, the dunking in the Palawan Passage aggravated a physical ailment caused from dengue fever.

“A Bad Day is a Bad Day to the End”

When the Japanese cleared the Palawan Passage late on October 23 and entered the Sibuyan Sea, Kurita switched command from the smaller Kishinami to the super battleship Yamato. While he still retained a large force, including five battleships and nine cruisers, American submarines had rattled the commander. Admiral Ugaki wrote of October 23, “A bad day is a bad day to the end.” It would only get worse.

Steaming in the waters off the eastern Philippine coast with his mighty force of aircraft carriers, Admiral Halsey eagerly anticipated action with the Japanese fleet. Halsey, known in the United States for his aggressive demeanor and bitter tirades against the enemy, had missed participating in the war’s major carrier actions to date. The Battle of the Coral Sea unfolded while Halsey ferried into position the bombers led by General Jimmy Doolittle in his famed 1942 Tokyo raid. A serious skin rash forced him to linger in a Hawaiian hospital while his subordinate, Raymond Spruance, led American forces to victory in the crucial Battle of Midway. Two years later, Admiral Spruance again led the American fleet during the Battle of the Philippine Sea.

Irritated at these absences, Halsey intended to compensate by engaging the Japanese in the next surface action. He knew the enemy fleet would most likely sortie in response to General Douglas MacArthur’s assault against the Philippines, so he prowled the Philippine Sea, searching for enemy carriers he was certain would appear. One possible path for the Japanese was to sortie from the Singapore area and approach the Philippines from the west. Since he sat with his carriers to the land’s east side, Halsey considered moving west through the narrow waters of the San Bernardino Strait to be in position to engage the enemy, should he actually appear.

Halsey’s superior, Admiral Chester Nimitz, quickly squashed this prospect. He reminded Halsey that his main responsibility was to cover the invasion forces in Leyte Gulf, not to pursue the enemy carriers. Nimitz admonished Halsey not to steam through the strait unless he received orders to do so.

With that plan negated, Halsey began sending his weary task groups, which had been at sea for 10 months, to Ulithi for a breather. On October 22, he ordered Task Group 38.1 under Vice Adm. John S. McCain off its station toward Ulithi and told Rear Adm. Ralph E. Davison to commence preparations for removing Task Group 38.4 from the line the next day.

Everything changed in the early pre-dawn minutes of October 23, when Halsey received the information forwarded by Darter that “MANY SHIPS INCLUDING 3 PROBABLE BBS” had been sighted. Halsey immediately canceled Davison’s departure and ordered his three task groups to refuel and move closer to the Philippine coast to reduce the flight time westward to the Sibuyan Sea.

Halsey’s carrier forces steamed into position on the night of October 23. Rear Adm. Frederick C. Sherman’s Task Group 38.3 took station off the Polillo Islands east of Luzon. To the southeast, 140 miles distant, Rear Admiral Gerald F. Bogan guided Task Group 38.2 (which included Admiral Halsey) off San Bernardino Strait, while Davison occupied the southernmost position off Leyte Gulf 120 miles southeast of Bogan.

Bull Halsey Orders the Strike

All three readied to launch search planes at daylight. To ensure he spotted the enemy, Halsey ordered an exhaustive examination of the western approaches to the Philippines. He gave each carrier group a search arc extending 300 miles, with teams of one Curtiss Helldiver bomber and two Hellcat fighters assigned to cover each 10 degrees of the arc. As backup, Halsey also stationed more fighters at 100-mile intervals to relay messages from the search planes to the carriers. Aboard his flagship, the carrier Essex, Admiral Sherman worried that this excessive deployment of fighters might hamper his ability to defend himself, but he went ahead with the orders without stating his objections.

All search planes lifted off at daybreak. At 8:20 am, one of Bogan’s pilots reported five battleships, nine cruisers, and 13 destroyers south of Mindoro Island and steaming into the Sibuyan Sea. Seven minutes later, Halsey ordered his three groups to move closer together, and at 8:37 am he issued the order, “Strike! Repeat: Strike! Good luck!”

All search planes lifted off at daybreak. At 8:20 am, one of Bogan’s pilots reported five battleships, nine cruisers, and 13 destroyers south of Mindoro Island and steaming into the Sibuyan Sea. Seven minutes later, Halsey ordered his three groups to move closer together, and at 8:37 am he issued the order, “Strike! Repeat: Strike! Good luck!”

Admiral Sherman had just turned his carriers into the wind to launch his strike when radar operators picked up three incoming enemy formations of 50 to 60 aircraft each from the west and southwest. His fear that he lacked enough fighter strength now materialized. He could either follow Halsey’s orders and launch an air strike or postpone the strike so his fighters could protect the ships, but he could not do both. He had little choice but to cancel the offensive strike so his fighters could intercept the oncoming enemy.

What he had spotted were Japanese land-based aircraft out of Luzon–the same aircraft Kurita had hoped would serve as his air support. They had instead been deployed against U.S. ships, as Japanese commanders believed the ships would be a more opportune target for their inexperienced aviators. In addition to the three air groups, a fourth group of 76 aircraft also approached from the Japanese carrier force that steamed down from the north.

A Navy Fighter Pilot’s Primary Task: Protect the Ship

Sherman hastily postponed the air strike against Kurita until his fighters dismissed the more threatening Japanese aerial assault. He launched every available fighter, far too few in his opinion, then turned his ships into “one of the nearby rain squalls for cover, like soldiers going into their fox holes. Throughout the day we played hide and seek in these squalls.”

Lieutenant Carl Brown was flying combat air patrol over the carrier Princeton when the Japanese struck. Although outnumbered, he and his fellow pilots quickly jumped into the fray. “We estimated that there were 65 fighters and 15 bombers in the attack,” Brown later recalled. “Ordinarily we would not have tackled 80 planes with eight Hellcats, but it was get them before they reached our ships. It had been drilled into us from the time we were in preflight school that the primary task of a Navy fighter pilot is to protect his ship.”

Brown and the other aviators did more than their share of protecting the carriers. In spite of their lesser numbers, American fighter pilots shredded the Japanese formations as if they had been stationary targets. It was just like the Marianas Turkey Shoot in which American fliers scored such huge tallies earlier in the year.

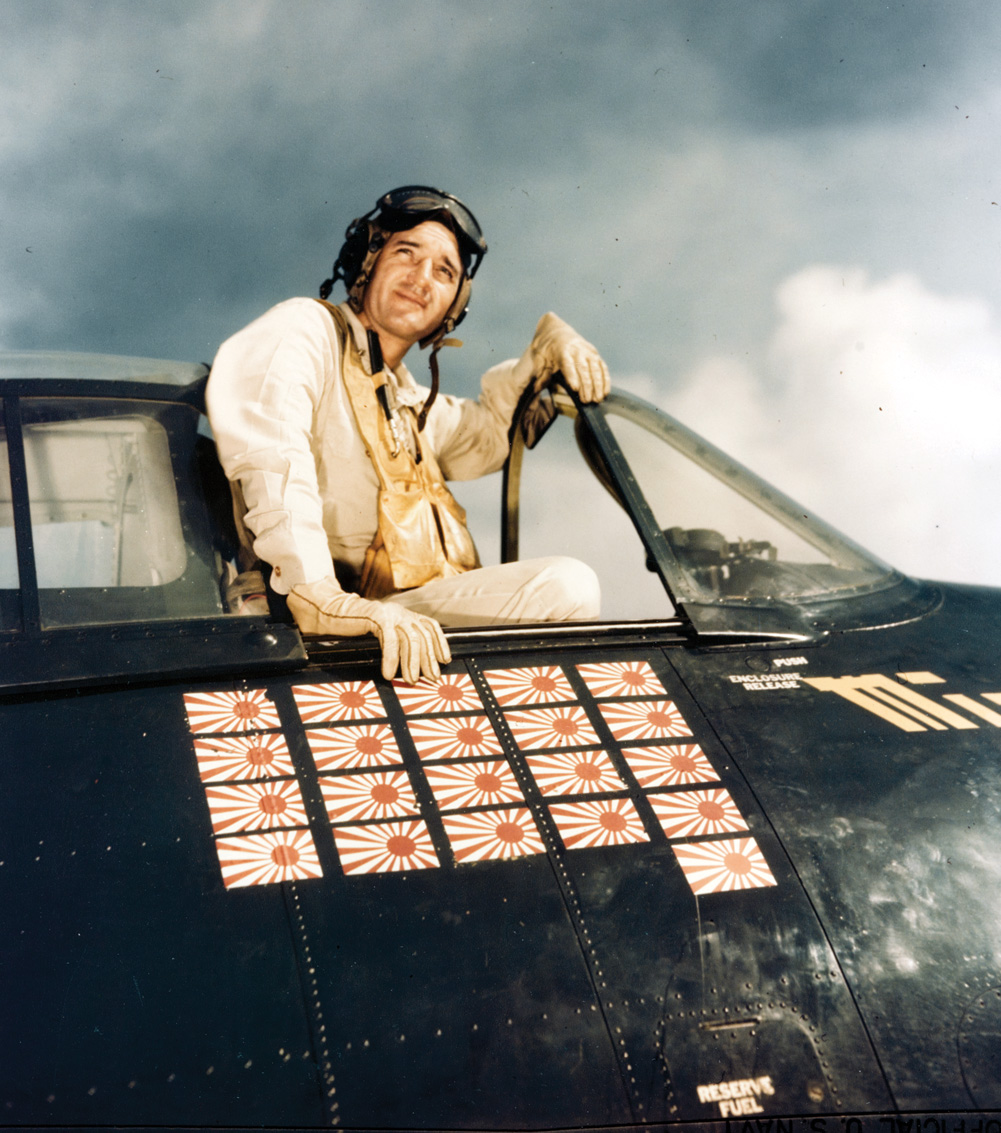

Commander David McCampbell was one of the aviators fortunate enough to have taken part in the Marianas slaughter. In one frantic day, he splashed seven enemy aircraft to become an instant ace. He could never guess that he would top that incredible performance this October 24.

When he received the order to intercept the enemy planes, McCampbell, followed by his wingman, Ensign Roy Rushing, wondered what to do. The pair of fliers faced an oncoming enemy force of more than 40 aircraft, so he radioed back to Essex’s combat information center, “My wingman and I are up here alone with about 40 fighters. What do you suggest that we do, attack them or not?” As the Fighter Director Officer, John Connally, later to be the governor of Texas, was not sure what the fliers should do, he replied, “Well, use your best judgment.”

McCampbell opted for the offensive. He and Rushing waited about 2,000 feet above the Japanese, who had formed into a tight circular formation labeled the Lufbery, to have the altitude advantage when the foe left the formation for their attack. When they saw the enemy break out of the Lufbery, McCampbell and Rushing executed repeated runs on the less experienced pilots. “I would pick out my plane, then he’d [Rushing] pick out his,” wrote McCampbell after the war. “We’d make an attack, pull up, keep our altitude advantage and speed, and go down again. We repeated this over and over. We made about 20 coordinated attacks.”

As the pair downed enemy planes, McCampbell marked the tally in pencil on his dashboard. At the end of the encounter, McCampbell had shot down nine enemy aircraft, while Rushing added another six. In the ready room after the melee, another aviator boasted that he had registered five kills that morning and asked how many McCampbell notched. The pilot lapsed into silence when he learned his fellow pilot shot down almost twice that number.

For his aerial feats, McCampbell received the Medal of Honor. His citation read, in part, “During a major fleet engagement with the enemy on October 24, Commander McCampbell, assisted by but one plane, intercepted and daringly attacked a formation of sixty hostile land-based craft approaching our forces … shot down nine Japanese planes and, completely disorganizing the enemy group, forced the remainder to abandon the attack before a single aircraft could reach the fleet … ”

The group that faced McCampbell failed to break through to the carriers, but at 9:39 am a solitary bomber from a different group took advantage while the Princeton recovered aircraft to sneak in and drop a 550-pound bomb that plunged through the middle of the flight deck forward of the elevator. Since the bomb left only a small hole as it continued deeper inside the carrier, Captain William H. Buracker, Princeton’s commanding officer, believed the damage could speedily be repaired. Aboard the Essex, Admiral Sherman also dismissed the bomb hit, “as I felt the Princeton was much too tough a ship for one hit by a 500-pound bomb to cause any very serious damage.”

“The Explosion Was as Surprising as it was Terrifying”

Both officers underestimated the seriousness. The bomb passed through both the flight deck and the hangar deck before stopping in the ship’s bakery, where it exploded and killed everyone stationed there. The bomb tore open the hangar deck, where aircraft, loaded with ammunition and fuel, erupted in flames. Buracker called for Salvage Control Phase I at 10:10 am, which removed 1,100 men from the stricken ship. Only firefighters to battle the inferno and gunners to defend the ship from subsequent air attacks remained on the burning vessel. When ammunition stored in lockers started exploding, Buracker ordered the gunners to abandon the ship.

By early afternoon, firefighters appeared to have the situation under control. The light cruiser Birmingham pulled alongside at 1:30 pm to take the carrier under tow. Crew members gathered in repair parties, brought out lines, manned guns, and started the intricate process of bringing a larger vessel under tow when, around 3:30 pm, an immense explosion blew open large portions of the Princeton and showered the Birmingham with lethal metallic fragments.

By early afternoon, firefighters appeared to have the situation under control. The light cruiser Birmingham pulled alongside at 1:30 pm to take the carrier under tow. Crew members gathered in repair parties, brought out lines, manned guns, and started the intricate process of bringing a larger vessel under tow when, around 3:30 pm, an immense explosion blew open large portions of the Princeton and showered the Birmingham with lethal metallic fragments.

“The explosion was as surprising as it was terrifying,” said a survivor afterward. “I think it can well be compared to a small volcano. A considerable portion of the after part of the Princeton was blown into the air and fell in the water astern. Flying fragments, some huge, some small, burst outwards and upwards, showering the deck of Birmingham from stem to stern.”

The men on Birmingham’s deck were caught in the open, their fates sealed by where they stood and which path the metallic missiles took. Men dropped as if cut by large scythes, and blood freely washed across the deck.

Despite the horror, men shook off their stupor and started helping the wounded. Their valor was matched by the calmness exhibited by those felled by the blast. “I really have no words at my command that can adequately describe the veritable splendor of the conduct of all hands, wounded and unwounded,” explained the Birmingham’s executive officer. “Men with legs off, arms off, with gaping wounds in their sides, with the tops of their heads furrowed by fragments, would insist, ‘I’m all right. Take care of Joe over there,’ or ‘Don’t waste morphine on me, Commander; just hit me over the head … ’ Terrible as the destruction was, it is a source of supreme gratification to know the heights of courage and forgetfulness of self to which one’s shipmates can rise.”

The Initial Raid Consisted of 45 Fighters, Dive-Bombers, and Torpedo Planes

Captain Buracker had no choice but to order the remaining crew members off. At 4:38 pm, after ensuring that no one alive remained aboard, Buracker stepped off the Princeton. The cruiser Reno fired two torpedoes into the carrier that sent her to the bottom. In all, more than 100 men from the Princeton and 220 from the Birmingham perished, while another 430 suffered wounds. Although the Birmingham’s starboard side looked more like Swiss cheese than a ship’s hull, she retained enough power and stability to slowly head back to port for repairs.

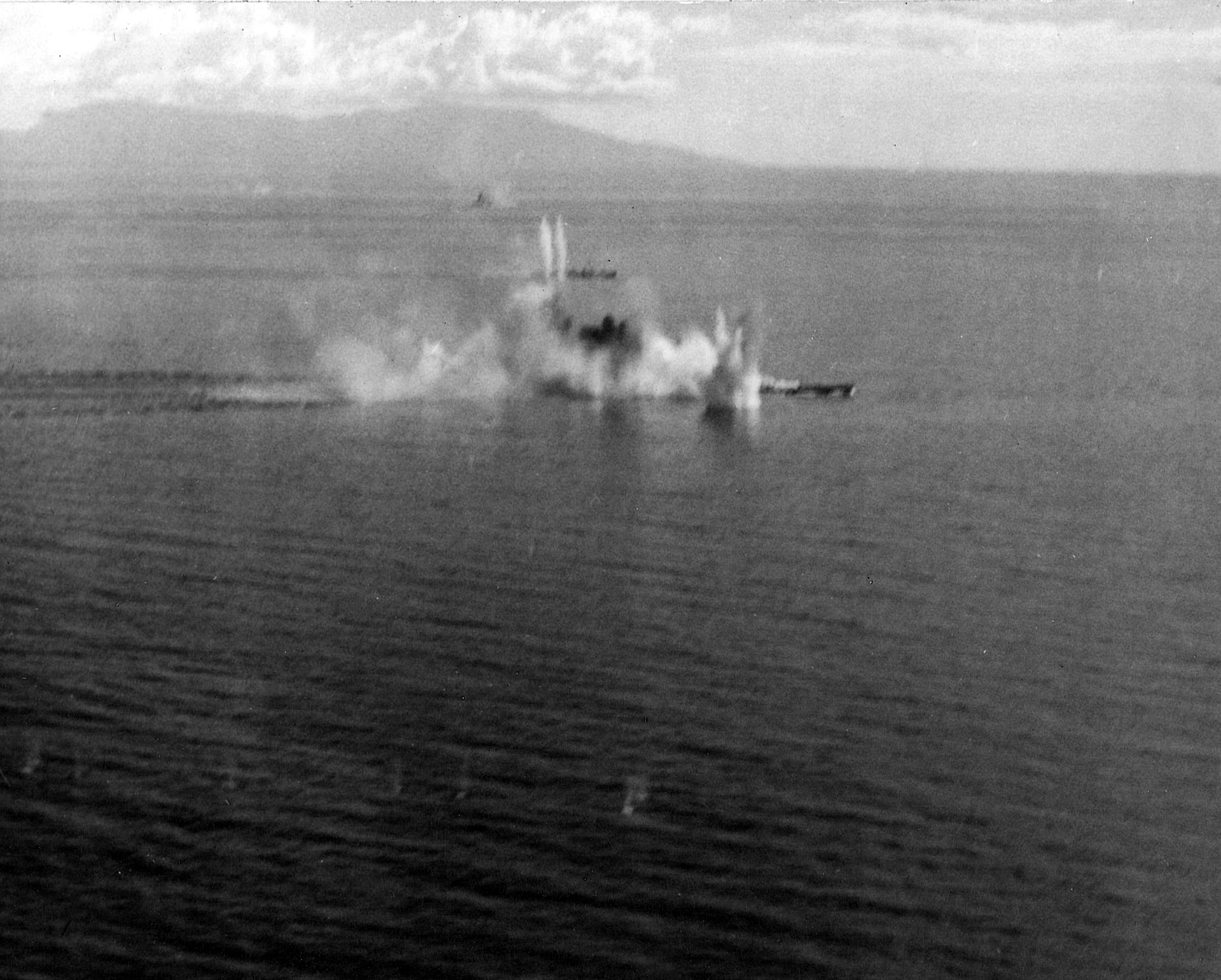

While Admiral Sherman repelled the Japanese air attack, Bogan and Davison launched their strikes against Kurita, now commanding from the super battleship Yamato. For four hours, from midmorning until early afternoon, American carrier planes hit Kurita’s forces steaming across the Sibuyan Sea on the Philippines’ western side five separate times.

The initial raid consisted of 45 fighters, dive-bombers, and torpedo planes from the carriers Intrepid and Cabot. Fair weather greeted the aviators, as fluffy clouds sprinkled a clear blue sky lightly buffeted with easterly winds. Below, verdant tropical isles with soaring mountain peaks breaking through green foliage dotted the turquoise waters. “The scene hardly suggested the bitter battle about to be fought in its environs,” Admiral Sherman later wrote.

The first aircraft started their runs at 10:26 am. The intensity of the Japanese antiaircraft barrage stunned American pilots, who did not know that the enemy had purposely strengthened each ship’s defenses to compensate for the lack of air cover. More than 100 guns boomed from Kurita’s battleships, including his heaviest batteries, while cruisers added another 90 guns per ship and destroyers close to 40. Antiaircraft guns shredded the peaceful skies with varied colors of shell bursts, casting lethal shrapnel toward the oncoming American planes. “The cumulative effect was terrific,” wrote one aviator of the pink-purple-and-white-hued eruptions that surrounded his aircraft on the way down.

The pilots, happily surprised at the absence of enemy fighters, droned toward their targets. The fighters descended first to send the Japanese scurrying for cover, then the torpedo planes and dive-bombers attacked against what they hoped would be a disorganized defense. Most aircraft focused on the giant battleship Musashi, whose reinforced steel plates absorbed most of the damage in this attack. The cruiser Myoko, however, had to turn back toward Brunei due to damage sustained.

After a second strike inflicted further damage to Musashi and other ships, Kurita dashed off a message to Admiral Ozawa inquiring whether he had succeeded in luring Halsey away from San Bernardino Strait. “We are being subjected to repeated enemy carrier-based air attacks,” Kurita informed Ozawa. “Advise immediately of contacts and attacks made by you on the enemy.” Kurita also asked for fighter help from Manila, but those aircraft were then busy attacking Sherman. The best he could hope for now was that Ozawa had removed from the scene some of the enemy forces arrayed against him.

“The Last Time I Saw Musashi, She was Stopped Dead in the Water”

Pilots in Halsey’s third air attack, which arrived over Kurita in the early afternoon, noticed the now-vulnerable Musashi struggling to make headway and concentrated their efforts against her. A string of bombs and torpedoes cracked the battleship’s sturdy hull, releasing a torrent of ocean water into Number 4 engine room. The subsequent loss of power caused Musashi to list.

Commander Dan Smith, the commanding officer of an air group from the carrier Enterprise, participated in this third attack. “When we winged over for our dive, we entered a cloud bank and the Jap guns went silent because they couldn’t see us. When we emerged from the clouds, they opened up again like the hammers of hell. I personally saw all eight of our torpedo planes score direct hits on the bow of Musashi, and saw five direct hits and three near misses from our bombers. The last time I saw Musashi, she was stopped dead in the water and her entire forecastle was awash.”

The final two attacks concentrated on sinking Musashi and blasting Kurita’s other major combatants. Aircraft from Admiral Sherman’s task group joined in now that the Japanese air threat had been removed by McCampbell and the other brave aviators. One bomb struck Musahsi’s tower housing the command bridges and 10 torpedoes slammed against her hull, while other aircraft enacted a nonstop attack on Kurita’s cruisers and destroyers. The hapless Japanese commander, steaming without an air cover to shield him, could do little but hope his antiaircraft guns could still the opposition before it inflicted significant damage. Later that day, after being pounded by 17 bomb and 19 torpedo hits, Mushashi sank, taking with her 1,100 men.

With the fifth and final air attack over, Halsey’s carrier aircraft had flown 259 sorties against Kurita. Japanese guns splashed only 18 American planes, such an insignificant number that Admiral Ugaki wrote in his diary, “The small number of enemy planes shot down is regrettable.” Against this meager loss, U.S. pilots inflicted heavy punishment. The battleships Yamato, Haruna, and Nagato sustained damage, the cruiser Myoko was forced back to Brunei for repairs, and Musashi had been lost.

As was often true in the war, Halsey’s aviators reported more damage than was actually inflicted. Exaggerated claims led the admiral to believe that Kurita was a beaten man commanding a shattered force, someone who now could be discounted in favor of searching for a larger quarry: enemy carriers. Halsey had missed several such opportunities earlier in the war, and he was not about to let providence steal another chance from him.

Consequently, he too quickly dismissed the importance of Kurita so he could embark on a search for enemy carriers. This would lead to near catastrophe. Despite his casualties, Kurita retained an armada of battleships, cruisers, and destroyers that could, if luck veered in his favor, badly sting the Americans.

“With Confidence in Heavenly Guidance, All Forces Will Attack!”

While Halsey turned his attention away from the Sibuyan Sea, Kurita pondered a decision of his own. His staff, fearing that additional American air attacks would gradually wipe out the force, urged him to reverse course and regroup. Kurita also knew that if he continued toward the Philippines at his current speed, he would enter the narrow San Bernardino Strait before darkness provided him some protection. The last thing he wanted to face was an air attack while steaming in narrow waters that prevented him from properly maneuvering.

At 3:30 pm, Kurita thus ordered his ships to reverse course and head west to move out of bombing range. Thirty minutes later, he informed Admiral Toyoda, “Were we to force our way through [the strait], we would merely make ourselves meat for the enemy, with very little chance of success. It was therefore concluded that the best course open to us was temporarily to retire beyond the reach of enemy planes.”

This measure by Kurita, however prudent for the safety of his men and ships, disrupted the entire timetable of the complex Japanese operation by seven hours, the time lost while Kurita retired. On the other side, Halsey made a false conclusion when American search planes spotted Kurita’s force reversing course. He assumed that Kurita was retiring, when in fact he was only regrouping and waiting for a better opportunity to approach.

When Kurita had steamed west for a few hours without any subsequent air attacks, he again considered rushing through San Bernardino Strait. Possibly the enemy had pulled back, which would allow Kurita to steam across the Sibuyan Sea and risk a night passage through San Bernardino. A message from Toyoda strengthened his resolve. “With confidence in heavenly guidance, all forces will attack!” ordered the admiral. Toyoda’s chief of staff prodded Kurita even more when he stated that the “change in schedule could mean failure for the whole operation. It is ardently desired that this force continue its action as prearranged.”

Kurita tossed caution to the wind. At 5:14 pm. he turned back toward the Philippines and sent a message to Toyoda stating, “Braving any loss and damage we may suffer, the First Striking Force will break into Leyte Gulf and fight to the last man.”

With the dual moves of Kurita again heading toward the San Bernardino Strait and Halsey turning his attention away from the strait and to the location of Japanese carriers, the first phase of the Battle of Leyte Gulf was over. American aircraft had inflicted punishing blows to Kurita, but they had been by no means fatal. Kurita retained sufficient power to seriously impede American operations in Leyte Gulf, should he succeed in fighting his way through. Halsey admitted as much when he wrote afterward, “The most conspicuous lesson learned from this action is the practical difficulty of crippling by air strikes alone, a task force of heavy ships at sea and free to maneuver.”

Kurita’s chief of staff, Tomiji Koyanagi, expressed similar sentiments. He admitted that Kurita had suffered heavy losses, but in a backhanded manner. “We had expected air attacks, but this day’s were almost enough to discourage us.” Had Halsey’s raids been more severe, Koyanagi would never have used the word “almost.”

Musashi’s Fate

Koyanagi blamed Halsey for allowing Kurita to later slip through San Bernardino Strait. Had Halsey ordered more air attacks than the five that occurred, he would have known that Kurita had not reversed for good and that he once more steamed toward the Philippines. Halsey could have then bided his time until Kurita steamed into his clutches. “If he had done so, a night engagement against our exhausted force would undoubtedly have been disastrous for us,” Koyanagi wrote. He added, “Thus the enemy missed an opportunity to annihilate the Japanese fleet through his failure to maintain contact in the evening of 24 October.”

Halsey should have been guarding the eastern exit of the strait, but when Kurita barreled through, much to his surprise, he found nothing but open water and a free path to Leyte Gulf. Only the gallant stand of Taffy 3, a group of 13 tiny escort carriers and their smaller escorts, later prevented Kurita from steaming into Leyte Gulf.

On the other hand, Halsey’s pummeling of Kurita and other events turned the Japanese commander into a timid leader. Within a 24-hour period, Kurita lost five ships to American submarines, had his flagship sunk under him, endured the embarrassment of being plucked out of the sea, watched as a series of American air attacks reduced his forces and left him no time to let down his guard, fretted that he could do little to fight back except employ his ships’ guns, and watched as enemy aircraft sank Musashi, one of the mightiest battleships afloat. The cumulative effect of these actions was to make the weary Kurita more hesitant, less aggressive, and more amenable to terminating his mission. The next day, when he encountered Taffy 3, these factors played a crucial part in the outcome.

At the Imperial Palace in Tokyo, Emperor Hirohito greeted the news with grimness. The course of events in the Philippines was not what he had hoped, and he feared that the path led only to the enemy dislodging his military from that crucial land. With resignation in his voice, Hirohito turned to an aide and muttered, “Ah so, Ah so, deska,” which meant, “It is so.”

Nice job John! Greatest engagement in the history of the US Navy