by Vince Hawkins

Born at Calcar in the Duchy of Cleve in 1721, Friedrich Wilhelm von Seydlitz was the son of a cavalry officer. Whether he was following a family tradition or a natural calling by joining the cavalry is no matter; Seydlitz’s flamboyant and dramatic career would far surpass even a proud father’s wildest expectations.

[text_ad]

At age 14, Seydlitz served as a page to the “Mad” Margrave Friedrich of Brandenburg-Schwedt. During these formative years in Friedrich’s service, Seydlitz developed the traits that would distinguish the rest of his life—a daredevil skill in horsemanship (he once rode through the sails of a windmill), a love of tobacco, and a notorious penchant for promiscuity. The former would serve him in good stead, while the latter would cause him great suffering and ultimately lead to his death.

Although Seydlitz would earn his fame as a commander of cuirassiers—the heavy cavalry of the army—he learned his trade in the light cavalry as Rittmeister, or captain, of a squadron in the Natzmer Hussar Regiment during the Silesian Wars (1740-1745). In 1752 he passed into the Württemburg Dragoon Regiment before finding his “niche” in the Rochow Cuirassiers in 1753. The rotation gave him an excellent understanding of the functions of all three branches of the cavalry and greatly contributed to his capabilities as a commander.

Seydlitz’s abilities were first noticed by Frederick at the Battle of Kolin in 1757. Here the then 36-year-old colonel of the Rochow Cuirassiers took command in mid-charge of the cavalry brigade to

Seydlitz’s abilities were first noticed by Frederick at the Battle of Kolin in 1757. Here the then 36-year-old colonel of the Rochow Cuirassiers took command in mid-charge of the cavalry brigade to

which his regiment belonged when the brigade commander was wounded. Continuing the charge, Seydlitz led the brigade against the enemy’s flank, sweeping aside two cavalry regiments and several infantry regiments. The charge presented Frederick with an opportunity that he desperately tried to exploit.

Although the battle ended in a defeat for Prussian arms, Frederick found consolation in the conduct of the man he described as “the only one who could exploit the full potential of his cavalry.” For his service at Kolin Seydlitz was promoted to major general, awarded the Pour le Merite, and given command of the cavalry in the upcoming campaign. It was during this campaign at the battle of Rossbach that Seydlitz won his greatest fame and established himself as a premier cavalry commander. Frederick, extremely pleased with Seydlitz’s performance, promoted him to lieutenant general and awarded him the Order of the Black Eagle.

Thus in less than six months Seydlitz rose from colonel to lieutenant general, an achievement unprecedented in Prussian military annals, but Frederick was never given cause to regret his decision. Brave, resolute, respected by his men, and able quickly and accurately to judge a battlefield situation, Seydlitz repeatedly justified his ever-growing reputation. Although having only a moderate education and some religion himself, Seydlitz held both in great regard. A stickler for military discipline and a hard drill master, he nevertheless abhorred corporal punishment and abolished its use in his regiment. In training his men, Seydlitz placed strong emphases on developing their swordsmanship, being one of the few cavalry commanders of the era to do so.

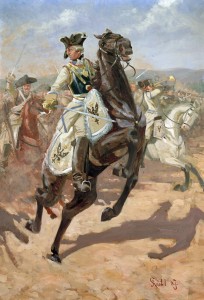

As for horsemanship Seydlitz put trainees on unbroken horses and watched to see how they handled it. For his own part, Seydlitz’s graceful horsemanship was renowned. In addition, his style and dress were imitated throughout the army. He loved military splendor and looked marvelous in uniform.

Seydlitz’s Penchant for Chasing Women Proved to be His Greatest Downfall

Seydlitz enjoyed a unique relationship with Frederick. The king had great respect for the cavalryman’s courage and ability, and held him almost in awe. Brusque and given to violent tempers with his other generals, Frederick nevertheless displayed deference in his meetings with Seydlitz, once “beg[ging] him to keep his pipe in his mouth, for he knew he was a passionate smoker.” Seydlitz was the only person able to challenge the king’s military judgment without reprimand or rebuff.

Seydlitz was equally deferential to his king. Once, during military maneuvers at Neisse in 1769, Frederick’s horse dumped him on the ground and ran away. Seydlitz’s regimental surgeon went to help the king, but Seydlitz told him to take no notice. Thus Frederick observed his troops through a telescope for 15 minutes while Seydlitz looked the other way as if nothing had happened.

If Seydlitz had a fault, it was his penchant for whoring. The consequences of his consistent bouts of debauchery so debilitated his constitution that the slightest wound rendered him incapacitated for months. A minor arm wound received at Rossbach kept him out of action for nearly four months because he had contracted a disease from “the society of a lady of high birth but lowly conduct.” Despite all this, and another painful wound to his hand in 1760, Seydlitz married the Countess Susanne von Hacke. She was 17 and he 39; the match unfortunately proved a disaster.

If Seydlitz had a fault, it was his penchant for whoring. The consequences of his consistent bouts of debauchery so debilitated his constitution that the slightest wound rendered him incapacitated for months. A minor arm wound received at Rossbach kept him out of action for nearly four months because he had contracted a disease from “the society of a lady of high birth but lowly conduct.” Despite all this, and another painful wound to his hand in 1760, Seydlitz married the Countess Susanne von Hacke. She was 17 and he 39; the match unfortunately proved a disaster.

At the end of the Seven Years’ War, Frederick created the Prussian Provincial Inspectorate, a body of royal inspectors, to oversee the management of the peacetime army. Seydlitz was appointed one of the inspectors with command of all the cavalry in Silesia. He justified the king’s trust, turning the Silesian cavalry into a superb fighting force that was admired even by Austria, Prussia’s enemy.

For nearly 11 years Seydlitz commanded the cavalry in Silesia from his regimental headquarters in Ohlau. His off-duty hours were usually spent entertaining friends at his estate, Minkowitz, near Namslau. In 1772 Seydlitz suffered a debilitating stroke. The following year he was again bedridden, this time with syphilis. Knowing of Seydlitz’s critical condition, Frederick visited him in August at Ohlau. He spoke with Seydlitz for over an hour, exclaiming again and again, “I cannot spare you! I cannot manage without you!”

Seydlitz, his nose ravaged by syphilis, turned his face into his pillow to keep the sight from his king. On November 7, 1773, aged 53, Seydlitz died of syphilis. The Prussian cavalry, which would never be the same without him, greatly mourned his passing. In the Wilhelmsplatz in Berlin, Frederick raised a statue to Seydlitz’s memory. And in his later years, when visiting Silesia, Frederick would sometimes stop at the Minkowitz estate and meditate at his subordinate’s tomb.

I recently learned that I am a great-great-great-great-great granddaughter to this great man.

*-*