By Peter Kross

By 1944, many top generals in Adolf Hitler’s army understood the war was lost and that they had better make arrangements to ensure their safety. Among the top cadre of military leaders who decided to take matters into their own hands were Martin Bormann and Heinrich Himmler. Before the war was over, these officers established a secret escape route out of Germany that led to South America and the Middle East, where they hoped to nurture the seeds of a “Fourth Reich,” which would continue the war at a later time. Bormann dubbed this new group “The Odessa,” an acronym for what might be roughly translated as “Organization of Former SS Members.” One of the most important Odessa members, and a man who would later play an important role in the future CIA-German intelligence alliance, was Reinhard Gehlen, a leading Wehrmacht intelligence officer.

A few years ago, under a successful Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) suit brought by a concerned citizen, the CIA opened up its previously closed Cold War files on Gehlen and his postwar activities with the CIA. The congressionally mandated Nazi War Crimes Disclosure Act brings to light the close relationship between the Gehlen Organization, which comprised many Nazi war criminals, and their post-war involvement with American intelligence services.

Reinhard Gehlen’s Early Career

Reinhard Gehlen spent most of his adult life in the service of the Third Reich. He joined the Army in 1920 and in the 1930s entered the Staff College, was promoted to captain, and gained a job with the Army General Staff. In 1940, he was promoted to major and became the liaison officer to Army Commander-in-Chief Field Marshal Walther von Brauchitsch. Later that year, Gehlen joined the entourage of Army Chief of Staff General Franz Halder. In July 1941, he was promoted to lieutenant colonel.

Gehlen saw action on the bloody Eastern Front and, in recognition of his superior talents and energy, was promoted to senior intelligence officer with the German General Staff concerning the Russian front. Practically speaking, he was head of the General Staff’s Foreign Armies East Division. Between this time and the end of 1942, he was approached by disaffected officers—among them Colonel Henning von Treschow, Colonel Claus von Stauffenberg, and General Adolf Heusinger—who were making secret plans for assassinating Hitler as a means of ending the war. Gehlen’s involvement in this cabal was minor.

By December 1944, Gehlen was a major general. His responsibilities were to gain information on the Soviet Army and study their battlefield tactics. The intelligence he gathered was lightly held by the German high command, who came to be distrustful of their own espionage services. In particular, Hitler did not trust the intelligence branch and looked askance at the information Gehlen was disseminating. Gehlen realized that his hard work was not being taken seriously in Berlin and he made plans to rectify the intolerable situation in which he found himself.

The plots to assassinate Hitler peaked on July 17, 1944, with a bomb’s explosion at a meeting of Hitler and his top aides. Hitler was only wounded in the attack, but he meted out a brutal revenge. Gehlen’s trivial part in the conspiracy was covered up and he escaped any punishment.

Making a Deal with the Allies

In April 1945, as Russian and American armies were converging on Berlin, the Third Reich was going down in flames. A large number of top German military officers, including Gehlen, decided it was time to cut their losses and make their own deals with the Allies. The most precious commodity Gehlen had to offer was his huge mass of intelligence files on Eastern Europe—the Soviet Union in particular—which he had secretly hidden in the Bavarian Alps, buried in steel drums. He knew that once the war was over, the United States would turn its attention not to a defeated Germany but to an increasingly powerful communist Russia. Gehlen was now in a position, vis-a-vis his intelligence files, to barter his freedom with the Allies.

To that effect, Gehlen surrendered to the U.S. Army Counter-Intelligence Corps (CIC) in Bavaria on May, 22, 1945. At first he was not recognized by his captors, who classified him as “just another Nazi.” Soon his real identity was discovered and steps were taken to rectify his personal situation.

The first Army officer to realize who they had in custody was Brig. Gen. Edwin Sibert, the G-2 (Army intelligence) of the Twelfth Army in Germany. Sibert spent many hours with Gehlen in long and arduous debriefing sessions, in which Gehlen regaled him with vital information. General Sibert was most impressed with Gehlen’s knowledge of the Russian military and Soviet political conditions. For example, Gehlen said that Stalin had no intention of surrendering Poland to the Western powers, and that Hungary, Romania, Bulgaria, and Czechoslovakia were to remain in the Russian political orbit. Gehlen revealed the names of a number of OSS officers who were secretly members of the U.S. Communist Party. He also provided biographical sketches of many of the top leaders in Moscow.

Using his clout, Gehlen forged a deal whereby he would turn over all his Russian intelligence files to the Americans in exchange for his freedom and that of a number of his top military colleagues, then in POW camps in Germany.

General Sibert contacted his superior, General Walter Bedell Smith, Eisenhower’s chief of staff, and told him about Gehlen’s offer, then waited for an answer. Ignoring Eisenhower’s order not to associate with German officers, General Smith told Sibert to continue his talks with Gehlen. William Donovan, the head of the Office of Strategic Services (OSS), Allan Dulles, the OSS station chief in Bern, and others in the War Department all agreed that the Gehlen connection was worth pursing.

On September 20, 1945, Gehlen and three of his most trusted aids were secretly flown out of Germany bound for Washington, D.C., on a plane provided by General Smith. Reinhard Gehlen had finally arrived.

Birth of the U.S.-German Intelligence Network

Once in the United States, Gehlen was taken to Fort Hunt, Va., where the newly created U.S.-German intelligence network was getting started. For 10 months, Gehlen spun vivid yarns about his personal and professional life. He said he was not really a Nazi, and that he would like to reestablish his intelligence network on behalf of the United States. His offer was accepted and Gehlen turned his considerable resources against the Soviet Union.

The Fort Hunt agreement between Gehlen and the United States led to a clandestine German intelligence organization created specifically to spy on the Soviet Union. Any information gathered would be shared with the United States. The new espionage agency would not be under the control of the United States, but would act independently. However, the United States would fund it until a new independent German state would come into existence. At that time, Gehlen’s agency would revert to the German government and put German foreign policies first.

The Gehlen Org

In July 1946, Gehlen was released from his official American captivity and, along with 350 former German intelligence agents of his choosing, left for Munich and began staffing his organization. Gehlen used a dummy corporation called the South German Industrial Development Organization to run his espionage unit. As time went on, he was able to staff his new group with over 4,000 undercover agents, or V-men as they were called, to serve throughout the Soviet Bloc nations. For years to come these men proved to be the CIA’s eyes on the ground in areas where no American could ever infiltrate.

The Gehlen Org, as it came to be known, also recruited thousands of the meanest, most despicable former members of the Gestapo, Wehrmacht, and SS officer class. Among those now under American jurisdiction were Alois Brunner, Adolf Eichmann’s most trusted aid; SS Major Emil Augsburg, who oversaw the murder of hundreds of Russians; and Klaus Barbie. Another Nazi employed by Gehlen was Franz Six, the exterminator of hundreds of Jews in the Smolensk Ghetto.

A German newspaper, the Frankfurter Rundschau, said of these men, “It seems that in the Gehlen headquarters one SS man paved the way for the next and Himmler’s elite were having happy reunion ceremonies.” Although the newly created CIA, which worked in unison with the Gehlen Org, was aware of the criminal backgrounds of many of his agents, it turned a deaf ear to the fact, wishing that it would eventually go away.

The Gehlen Org supplied much needed intelligence on developments inside the Warsaw Pact nations. In addition, Gehlen’s spies secretly made their way into Russian-occupied Eastern Europe and tried to ferment revolutions among the dissatisfied groups who were opposed to Soviet rule. These agents oversaw the clandestine air drops of agents by American-supplied aircraft behind the Iron Curtain. Hardly any of these parachute drops succeeded, however, because the Russians always seemed to be one step ahead.

Gehlen’s Mixed Results

By 1946, when Gehlen began his eavesdropping activities behind Russian lines, the CIA was beginning its own clandestine efforts to infiltrate agents into Russian-held territory and ferment revolutions. On one such mission, called “Operation Sunrise,” about 5,000 anti-Communists of Eastern European and Russian origin were given espionage training at a camp named Oberammergau. Agents from this mission soon infiltrated into the Ukraine, which was not entirely under Russian control. Another mission run by the Gehlen Org, dubbed “Operation Rusty,” was strictly an intelligence-gathering effort directed against many of the dissident German organizations in Europe. Another facet of the Gehlen Org’s work was to monitor the size of the Russian missile fleet, which was an increasing concern among the Western Allies.

Most of these infiltration missions were dismal failures. Over time, the Soviets were able to infiltrate their own counterspies into the Gehlen Org and tipped off their counterparts whenever a mission was planned. Another person who gave advance information to the Russians in the late 1940s and early 1950s about the CIA raids was Adrian “Kim” Philby, who was the British intelligence liaison with the CIA. Philby had been an undercover agent for the Soviet Union during World War II and remained in that position when the war ended.

One operation that was blown from the beginning was an anti-Communist mission dubbed WIN, whose target was Poland. The Gehlen Org made contact with WIN, a Polish underground group supplying the West with military information on Soviet troop movements. U.S. agents gave WIN’s members intelligence information as well as military supplies to conduct hit-and-run raids inside Poland. By 1952, many of WIN’s agents had been compromised and what little information came back to the West was of little use. In the end, the West discovered that Soviet intelligence services had created WIN in the first place.

Gehlen used the American fear of a sudden Soviet invasion of West Germany to his own advantage. To demonstrate his intelligence prowess to the Allies, on numerous occasions he used bogus information to convince them that the Russians were planning an imminent strike against the West.

Despite these fiascoes, Gehlen’s forces were able to score a number of intelligence successes. For example, Gehlen’s agents uncovered the secret Russian assassination unit called SMERSH. They helped in the secret construction of the Berlin Tunnel, by which Americans were able to burrow beneath the Berlin Wall and monitor signal intelligence coming from the Soviet forces in East Germany. They also played a part in snatching a copy of a secret speech given by Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev in which he lashed out at the crimes of the Stalin era.

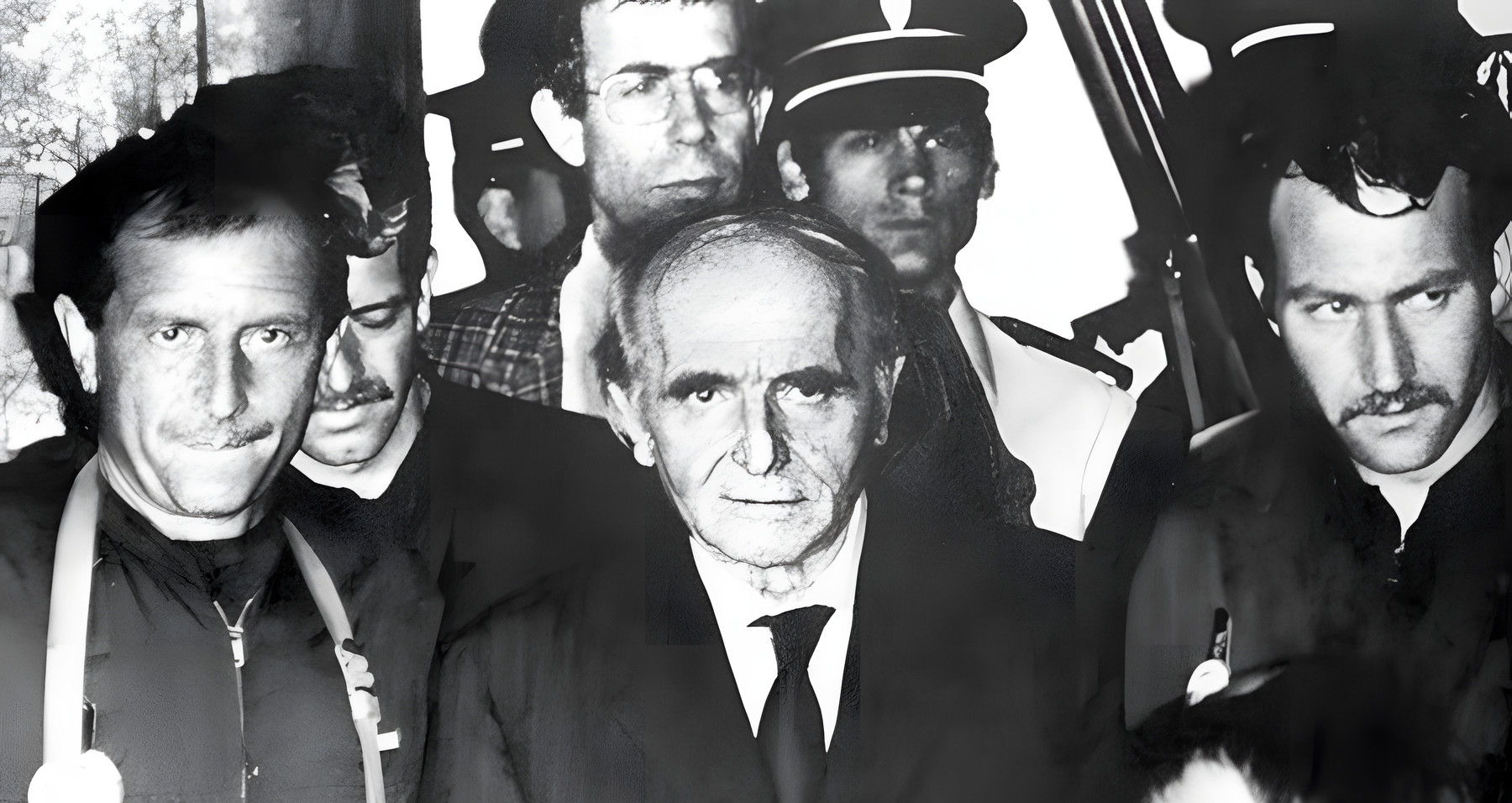

Gehlen and the Ratline

A major and odious sideline of the Gehlen Org was its helping former Nazi military officials to escape to South American and other parts of the globe. This was the so-called Ratline in which former SS men used forged documents provided by Gehlen, U.S. intelligence, and members of the Catholic Church. Gehlen never told his American colleagues about the illegal travels of these men, many of whom were wanted for war crimes. Among those who took advantage of the Ratlines was Klaus Barbie, who fled to Bolivia, where he lived for years under the alias “Klaus Altman.” Decades later he would be caught and returned to France to stand trial for his crimes there during the German occupation.

In April 1956, the Gehlen Org was reassigned to the new West German government and called the Bundesnachrichtendienst, or BND. Gehlen held his position as head of the BND until April 1956, when he was forced out because of a political scandal in the ranks. He retired in 1968 and died in 1979.

The Nazi War Crimes Disclosure Act

In 1998, the U.S. Congress passed the “Nazi War Crimes Disclosure Act,” which opened thousands of previously classified documents held by the CIA concerning its decades-long secret relationship with Reinhard Gehlen and his Org. Writer Carl Oglesby filed a Freedom of Information Act suit to free up the records (totaling 18,000 pages).

Part of the FOIA release was a two-volume CIA history called Forging an Intelligence Partnership: CIA and the Origins of the BND, 1945-49. In one document, the CIA says this about Gehlen’s character and personal traits: “Honest and idealist … enjoys good food and wine … unprejudiced mind ….” Other observers are not so upbeat about Gehlen. Eli Rosenbaum, director of the U.S. Justice Department’s Office of Special Investigations, said, “The real winners of the Cold War were Nazi war criminals, many of whom were able to escape justice because the East and West became so rapidly focused after the war on challenging each other.”

Commenting on the release of the Gehlen report, author Christopher Simpson, who wrote a book called Blowback: America’s Recruitment of Nazi’s and Its Effects on the Cold War, was told the following by an unnamed CIA source: “The Agency loved Gehlen because he fed us what we wanted to hear. We used his stuff constantly, and we fed it to everyone else—the Pentagon, the White House, the newspapers. They loved it, too. But it was hyped-up Russian bogeyman junk, and it did a lot of damage to this country.”

Whatever the merits of the Gehlen-CIA connection, the newly released files give us a better understanding of the secret forces afoot during the height of the Cold War.

What happened after the war was disgraceful for the USA. Real criminals went free and were actually treated with respect and given preferential treatment. For more details Read the book:

Operation Paperclip: The Secret Intelligence Program that Brought Nazi Scientists to America

The “remarkable” story of America’s secret post-WWII science programs (The Boston Globe), from the New York Times bestselling author of Area 51.

In the chaos following World War II, the U.S. government faced many difficult decisions, including what to do with the Third Reich’s scientific minds. These were the brains behind the Nazis’ once-indomitable war machine. So began Operation Paperclip, a decades-long, covert project to bring Hitler’s scientists and their families to the United States.

Many of these men were accused of war crimes, and others had stood trial at Nuremberg; one was convicted of mass murder and slavery. They were also directly responsible for major advances in rocketry, medical treatments, and the U.S. space program. Was Operation Paperclip a moral outrage, or did it help America win the Cold War?

Drawing on exclusive interviews with dozens of Paperclip family members, colleagues, and interrogators, and with access to German archival documents (including previously unseen papers made available by direct descendants of the Third Reich’s ranking members), files obtained through the Freedom of Information Act, and dossiers discovered in government archives and at Harvard University, Annie Jacobsen follows more than a dozen German scientists through their postwar lives and into a startling, complex, nefarious, and jealously guarded government secret of the twentieth century.

In this definitive, controversial look at one of America’s most strategic, and disturbing, government programs, Jacobsen shows just how dark government can get in the name of national security.