By James K. Swisher

In the lengthening shadows of a late October afternoon, a column of tired marchers attired in dusty, fringed hunting dress emerged from the trees along the north bank of the Kanawha River, raising an exhilarating shout upon sighting its confluence with the Ohio. Moving to the beat of an awkward drummer and the high, shrill squeal of fifes, which scattered birds across the sky, the flower of Virginia’s upland militia filed into the triangular meadow formed by the coalesce of the two rivers. Despite their growing dissatisfaction with the Crown, these volunteer frontiersmen were responding to an appeal by the Royal Governor of Virginia, John Murray, Earl of Dunmore.

As they settled about twinkling campfires in the chilly, moon-washed night, the marchers carefully surveyed their surroundings. A more attractive camping location could scarcely be found. Large trees, scattered park-like about the site, provided shade, and springs of cold, pure water were plentiful. The multihued leaves turning red and ochre displayed the eye-filling beauty so characteristic of an Appalachian upland autumn. European army officers would scarcely have recognized the assemblage as a military force, because few uniforms were in evidence and discipline seemed voluntary.

Most of the soldiers wore long hunting shirts or frocks of heavy linen dyed to various hues. Woolen stockings stretched almost to the thigh with linen or woolen shirts, breeches or trousers, and shoes or moccasins. Headgear included tricorns made from wool. The firearms these men so carefully protected were flintlocks, primarily the recently developed American long rifles but with a scattering of English-style muskets. From broad, beaded belts hung leather shot bags and elaborately carved powder horns. Tomahawks and scalping knives completed their equipment. They moved with a carefree shuffle that was almost a swagger. So cocksure and confident were these young militiamen that commissary officer William Ingles remarked later: “We thought ourselves a terror to all the Indian tribes on the Ohio.”

This hastily organized militia army of slightly more than a thousand Virginians was led by Militia General Andrew Lewis, a native of Staunton, Va. The stout, brown-eyed Lewis, descended from Presbyterian stock that had initially settled in Ireland, was an experienced colonial military commander. He was one of those brave, intrepid souls who had accompanied George Washington to the Forks of the Ohio (present-day Pittsburgh) and assisted in the futile defense of Fort Necessity in 1754. Promoted to major of militia, Lewis followed British General Thomas Forbes to the same region on his tragic 1758 expedition to capture Fort Duquesne. Lewis was wounded and captured by the French. Reportedly slain, instead he was conveyed by his captors to Montreal, then to Quebec, but proved such an intractable prisoner that he was exchanged in November 1759.

Andrew Lewis was described by most who knew him well as “of vigorous intellect, unquestionable courage, and uncommon persistence.” His reputation as a frontier militia officer grew, tempered in the defense of isolated settlements and eager for the dogged pursuit of hostile raiders. Lewis presented a stern, humorless public countenance, accompanied by a reserve that rendered his presence less than engaging. Highly authoritarian, he was respected and usually obeyed by his followers for his obvious abilities, but his personality forbade true closeness.

Lewis’s militia force was composed of landholding farmers from the backcountry Shenandoah Valley counties of Augusta, Fincastle, and Botetourt. These spacious, thinly populated counties provided their citizens with freedom from the bonds of authority, encouraging the development of Mr. Jefferson’s ideal “republic of farmers; the bedrock upon which the republic should be based.” Provincially absorbed in local and personal affairs, these stout backwoodsmen were only a few generations removed from their Celtic or Germanic roots. Yet already they were expert hunters, skilled in the use of their long rifles, and accustomed to living on the disordered borderlands of civilization where violence was a way of life. Most developed a rural individualistic lifestyle supported by their belief in a strong, evangelical, protestant God and an equally intense distrust of any authority figure. They were almost impossible to discipline, as armies were wont to attempt, but could prove terrible, violent, and effective soldiers if properly motivated. Uninhibited, they replied to the war-whoop of the Shawnee with the long-drawn hallo of the hunter.

One of the Finest Fighting Units Produced by American Revolutionary Armies

Colonel Charles Lewis, 38-year-old brother of Andrew Lewis, led the Augusta County Regiment while Colonel William Fleming directed the unit from Botetourt County. Colonel John Field commanded an independent company from Culpeper County to which various other smaller units were attached.

Marching in the ragged ranks were scores to whom fame and fortune would appear in the eventful days to come. Seven members of the unit would rise to the rank of general in the Revolutionary armies. From these sturdy frontiersmen came the brave adventurers who waded with Colonel George Rogers Clark in the drowned lands along the Wabash, struggling to capture Vincennes. Private Samuel Barton, Captain Thomas Posey, and dozens of others would form the backbone of Daniel Morgan’s riflemen, to be recognized as one of the finest fighting units produced by American Revolutionary armies and critical to the American defeat of Johnny Burgoyne at Saratoga.

Colonel Fleming would serve briefly as governor of Virginia. Four additional state chief executives attended the army. Young Isaac Shelby, marching in a company commanded by his father, would become the first governor of Kentucky, while John Sevier would serve Tennessee as both governor and U.S. Senator. Likewise Captain George Matthews would become chief executive of Georgia and Captain John Steele would hold the identical position in Mississippi. Posey would serve as governor of the Indiana Territory. Six years hence, William Campbell, John Campbell, Evan Shelby, and John Sevier, all serving as colonels, would lead the sudden gathering of mountain men who surrounded and destroyed Patrick Ferguson’s Loyalist Legion atop Kings Mountain, thus providing the American Revolutionary Army with its initial southern victory.

This unmilitary-appearing but talented group of Virginians, poised on the edge of civilization, was but a portion of a broader plan envisioned by Lord Dunmore. Since 1768, when a treaty negotiated at Fort Stanwix, NY, altered the land boundaries between settlers and Native Americans, colonial migration westward increased, as had, correspondingly, Indian aggressiveness. This agreement established the demarcation boundary between Indian land and those areas open to settlement at the Ohio River; most of the eastern tribes were compressed into an area north and west of that river’s curving arc. Displeased with white migration, a number of tribes, including the militant Shawnee, formed an alliance under the creative leadership of their war chief, Cornstalk. The Miami, Ottawa, Delaware, Wyndot, and Mingo placed their warriors under his control, an unusual action for tribally conscious Indians. As the two implacable enemies, colonial settlers and native defenders, drew nearer in proximity, the clash of their cultural values brought about open but undeclared warfare—a merciless struggle pursued by both parties to the death. As Indian raids increased east of the Ohio and atrocities demanded redress, Virginia Royal Governor Dunmore requested and received authority from the Virginia House of Burgesses to pursue war with the Shawnee and their allies.

The imperious and slightly overbearing Dunmore, born John Murray, son of William Murray, had initially been appointed governor of New York. But in 1771 when Governor Berkeley died in office, Dunmore was assigned to administer Great Britain’s most populous colony. An experienced soldier of the 3rd Regiment of Foot Guards and an admirer of horse racing and dancing, Murray and his popular wife, Lady Charlotte, were initially well accepted by the socially conscious Virginians. The auburn-haired, brown-eyed Scotsman, who often wore a kilt, possessed the Stuart charm and willfulness. Dunmore enrolled his three sons in the College of William and Mary and settled into the limited social scene of Williamsburg, Va.

John Murray came to the colonies like most royal appointees, with the intent of increasing his own personal fortune through land holdings. Vast acreages of land along the Ohio seemed available for possession and reapportionment under his patronage if freed from native control. Thus, Dunmore rapidly became a willing ally of the Virginia land speculators, who were scheming to obtain acquisitions of enormous scope, and he decided to launch a punitive campaign designed to break Indian power along the Ohio River. Dunmore did not pursue a war of annihilation but rather one of land acquisition, arguing that the mother country must allow her colonists to extend their territorial holding because, he reasoned, in this manner these pioneers would be longer satisfied under English rule.

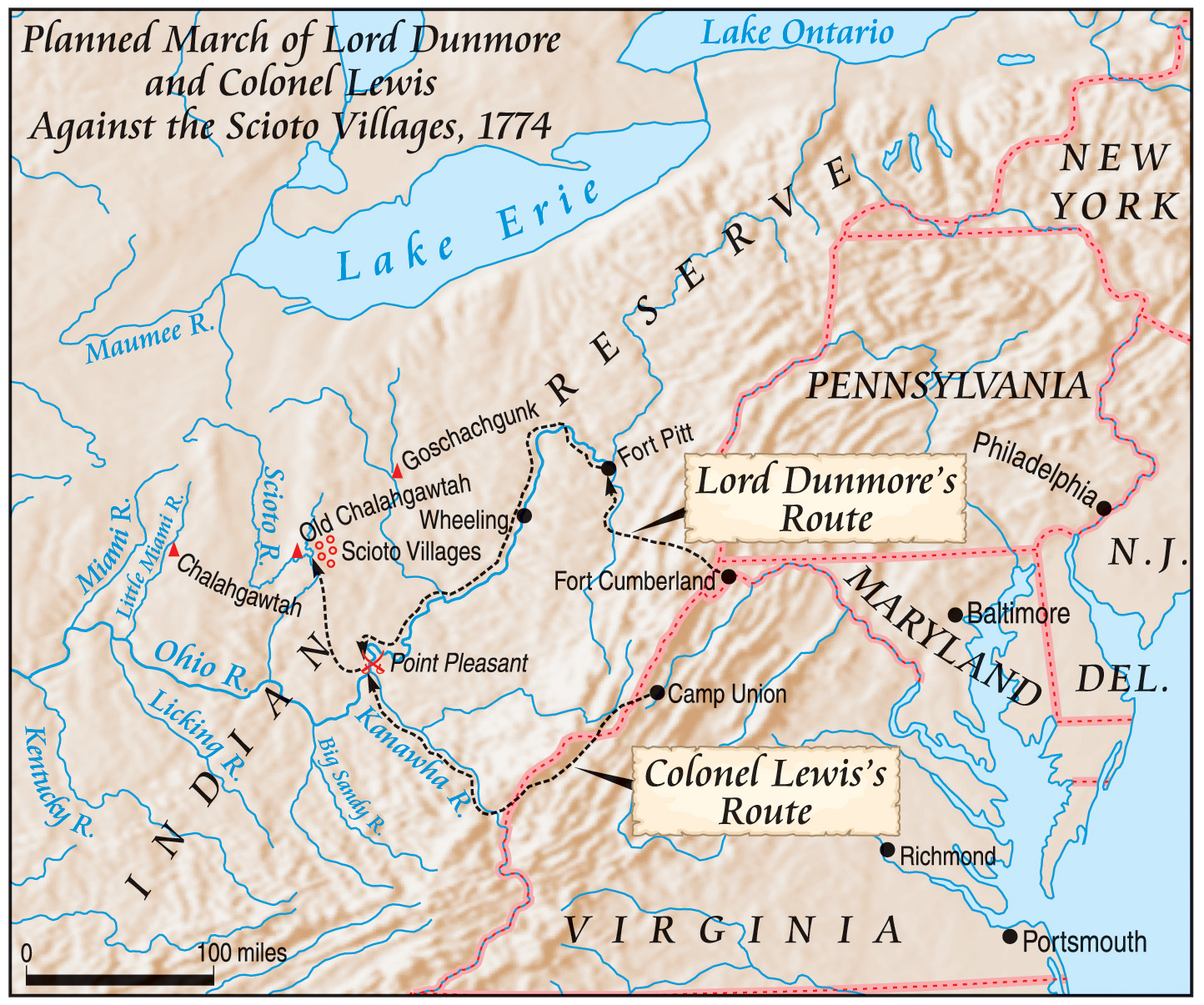

The governor determined to initiate a two-pronged offensive using 2,500 Virginia volunteer militia. He would personally command a division of 1,500 soldiers who would march northwestward to Fort Pitt (the renamed Fort Duquesne). At that point boats and canoes would be assembled to enable the division to float down the broad Ohio to an intersection with the westward-flowing Kanawha. General Andrew Lewis’s Division, advancing overland through some of the most rugged country on the frontier, would meet Dunmore at the confluence. Together they would advance on the Indian villages across the Ohio, overwhelming them with power or punishing them sufficiently to deter further incursions. To the amazement of the militia, Lord Dunmore marched alongside them on foot, carrying his own knapsack.

On August 12, General Andrew Lewis conferred with his principal lieutenants, reviewed their recruiting efforts, and announced a rendezvous on September 1 at the “Great Levels” on the Greenbrier River, an area with which he was familiar, having surveyed there as early as 1754. Lewis named the site Camp Union (currently Lewisburg, W.Va.), and when he arrived several days before the end of August he found an eager Augusta County regiment already encamped. Setting up lean-to shelters along the small streams, the frontiersmen smoked their pipes, swapped yarns, and impatiently waited orders to advance. Large packhorse herds, assembled under the supervision of Major William Ingles, grazed peacefully in the fields along the Greenbrier River. Supplies were adeptly dispatched by wagons over Warm Springs Mountain from Staunton to the end of the trail. From that point all ammunition and supplies were carried on packhorses, which were assigned three to a company. A small herd of cattle accompanied the column—rations on the hoof.

Indian Ambushes Caused Panic Among Soldiers

On September 6 the vanguard of the army, the Augusta Regiment of Colonel Charles Lewis, marched out of Camp Union accompanied by 500 packhorses carrying 54,000 pounds of flour. The frontiersmen slashed a wide path through the forests toward Elk Creek where they would make camp and begin construction of canoes. Captain Matthew Arbuckle, a local resident and an experienced woodsman, led the long file of men and horses. Lewis’s marching orders stated that the column would move with horses, cattle, and the main body of troops in the middle of the column with an advance and rear guard of 200 men each. The entire column of marchers was to be encircled by flankers. To the particular amusement of the frontiersmen, fifers and drummers accompanied each regiment to relay commands, a reminder of Lewis’s British military roots. If attacked, the column was to form a circle, stand fast, and await further orders. Such tactics should hopefully prevent the panic that often followed Indian ambush.

Hacking through the dense forest, the Augusta volunteers scaled steep defiles, forded fast-flowing streams, and encountered more rattlesnakes than any had previously seen. Upon reaching bottomland at Elk Creek, the column turned downstream to its junction with the Kanawha River, near where Charleston, West Virginia’s state capital, now stands. The exhausted Augusta riflemen paused and began erection of a blockhouse to shelter their provisions. Canoe manufacturing was initiated, for these craft were essential to transport supplies down the wide, swiftly flowing Kanawha. On September 12 Lewis marched out of Camp Union with the second contingent of troops composed of Fleming’s Botetourt Regiment and Field’s combined unit. The bulk of Colonel William Christian’s Fincastle unit stayed at Camp Union, guarding the remaining provisions until the packhorses at Elk Creek could return.

The second column moved by a slightly different route. Unencumbered by so many horses, they followed a buffalo trail for some distance then climbed directly over the mountains to the Gauley River, then on to the Kanawha. On September 21 they filed, open-mouthed, past burning springs where subterranean natural gas leaked to the surface and was periodically ignited by lightning. By the 23rd the column united with Charles Lewis and his regiment on the Elk. The soldiers completed the canoes while Lewis sent out scouts, who encountered little sign of Indians.

Shawnee, however, lurked nearby all along the line of march, and each move of the “long knives” was noted and reported to Cornstalk.

A muster or military review was conducted on September 30 with much shouting and the discharge of a thousand rifles, gunfire echoing from the surrounding mountains. In high spirits on the following day, the long files moved out of Elk Creek camp, bound for the Ohio. They followed a narrow footpath along the northeast bank of the Kanawha as the heavily laden canoes kept pace on the river. Lewis advanced a company led by his son, John, and covered his right flank with a hundred-man unit. At length, on October 6, the signifying shout arose as the head of the column filed from the tree line and sighted the Ohio, 400 yards wide and flowing with a current as quiet as night. At the junction of the two streams, a meadow-like park provided an extensive view up both rivers, hence the name endowed by frontier scout Simon Kenton, “Point Pleasant.”

As the marchers prepared mess fires on the triangular point, the stars hung so low over the Ohio River that one seemingly could touch them. A feeling of melancholy isolation prevailed throughout the army that first night, for although their exhausting, 160-mile march was complete, the future was shrouded in mystery. Dunmore’s Division, expected to arrive first, was nowhere in sight, and despite deep confidence in their own prowess these hardy militia-men realized they were encamped in the land of their enemies.

Dunmore had stoutly supported Virginia’s claims to these western lands, arguing often with representatives from Pennsylvania over the Forks area and the ownership of Fort Pitt. Eventually the Pennsylvanians backed down before the militant Virginians, until the Indian threat brought on an uneasy truce between the parties. The governor changed his tactics often as the campaign progressed, based upon information of dubious value. Dunmore’s indecisiveness can be partially attributed to his lack of confidence in his scouts. But Chief Cornstalk’s ability to conceal his true purposes amplified Dunmore’s information deficiency.

By late September, the governor decided not to proceed directly to Point Pleasant but to leave the Ohio River and to strike out westward from a point higher upriver. Clearly he wished Lewis to proceed across the Ohio at Point Pleasant and unite with his force. At this juncture, coordination between the two men—according to the testimony of those present in both army divisions—became extremely clouded. Just how much Dunmore’s alterations of plan were actually communicated to Lewis is yet undetermined. One testimony states that notes for Lewis were supposedly left in a hollow tree; another claims that a message from Dunmore was delivered by Simon Girty and so enraged Lewis that he beat the messenger about the head with his walking stick. Years later a number of officers with Lewis, including his son John, avowed that absolutely no communication took place between the two men. But it seems logical to conclude that Lewis either knew of Dunmore’s tactical alterations or that he deduced that some change in plan had occurred, because he did not prepare to fight at Point Pleasant and seemed ready to cross the Ohio for a march west. It’s virtually impossible to further decipher the level of communication between the two, except to determine it was less than required and almost proved fatal.

At Point Pleasant, Lewis ordered William Sharp and William Mason to travel upriver toward Fort Pitt in search of contact with Dunmore. Then, at dawn, all hands turned to work. Canoes, heavily laden with supplies and ammunition, were unloaded; necessary houses were constructed for each company; and rude shelters of pine boughs were built. A large log pen was erected to contain the cattle at night. On October 9, the Reverend Mr. Terry presented a lengthy sermon attended by all. Resting in the afternoon, the soldiers listened to the tales of a trader who described the savage appearance and extraordinary fighting abilities of the Shawnee. Few soldiers seemed concerned—the enemy was believed to be far away. But the little army was in for an expeditious surprise.

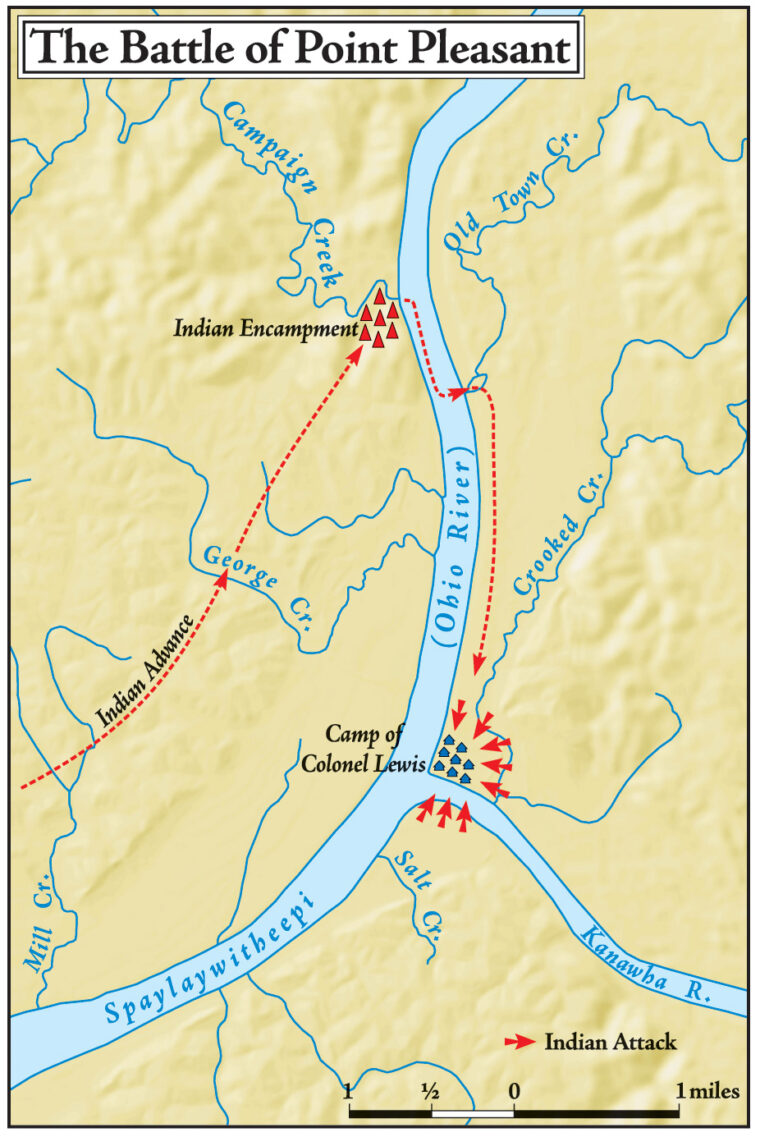

During the early hours of October 10, Cornstalk stealthily crossed the Ohio with an allied Indian force of 800 to 1,100 warriors; they grounded their canoes and rafts in Old Town Creek, less than five miles upriver. Camping within two miles of Lewis’s force, the hostiles prepared to attack at dawn. Painted for war, the Indians slipped quietly through the forest toward the glow of campfires barely seen through an increasing ground fog. Armed with lightweight smoothbore flintlocks obtained from French traders, the Indian warriors were prepared for close combat. These inaccurate trade guns became formidable weapons at close range when loaded with three to ten buckshot and a musket ball. A quick rush of the sentries and the warriors could explode from the fog onto the sleeping militiamen.

Andrew Lewis, frustrated at every turn by Dunmore’s silence, for once experienced some good fortune. Tired of stringy beef, two Virginia soldiers arose early and slipped unobserved out of camp. James Mooney and Joseph Hughey moved furtively up the Ohio scanning the riverbank for turkey or deer. Emerging from a pocket of dense fog, the duo confronted “five acres of Indians.” Hughey fell under the initial volley, shot down by Tavender Ross, a white renegade. But Mooney was more fortunate; ducking back into the fog, he sprinted toward camp screaming a warning. Almost concurrently, two hunters from Shelby’s Company, Sergeants James Robertson and Valentine Sevier, also out early, reported the sighting of hostiles.

Immediately the militia soldiers rolled out of their blankets, checked their flints, and fell into company formations. Lewis, believing the enemy to be a scouting force, dispatched two detachments, each of 150 men, under Colonels Lewis and Fleming to confront the advancing hostiles. Fleming’s Botetourt men probed forward along the Ohio riverbank while Lewis’s Augusta force advanced parallel, but farther inland abreast the Kanawha. After moving forward almost a half mile the columns were abruptly checked about sunrise by a hail of enemy gunfire.

Colonel Charles Lewis forged to the front, conspicuous in his red officer’s waistcoat. Such a target could not long be ignored and he was soon down, shot in the lower abdomen. Reportedly, Lewis exclaimed, “I am wounded but go on and be brave” as he was carried rearward to his tent by Captain Murray, his brother-in-law, and William Bailey. His detachment wavered and began to slowly fall back. The pressure of the Indian fire then fell upon Fleming’s unit. Within minutes Fleming, attempting to realign his forces, received a serious wound to the chest and was hit twice in the left arm. Fleming walked cooly to the rear.

Colonel Field bravely rallied forward with 200 colonial reinforcements, stabilizing the line. As the Indian onslaught crested, Field, despite sheltering behind a tree, was struck in the head and slain. A fellow officer stated that “Field was shot at a great tree by two Indians on his right as he was endeavoring to get a shot at a hostile on his left.” Captain Evan Shelby took command of the hard-pressed colonial line and gradually organized a continual line of resistance that stretched from the Ohio on the left flank to the Kanawha on the army’s right. Although it was restrictive to rapid maneuver, the position could not be flanked. Individual soldiers from the encampment began to arrive and fill in the line wherever gaps existed. Each soldier found cover behind a rock, tree, or stump and fought his individual war. In the heavy fog and thick, hanging gunsmoke the Indian warriors pushed in close and a melee of hand-to-hand fighting resulted. Neither party could drive the other and neither would retreat. Rifles and muskets were used as clubs, as were tomahawks, knives, hands, and feet. No quarter was asked and none given.

Cornstalk’s voice could be heard above the ear-splitting din as he shouted, “Be strong, be strong!” Taller than his followers and easily recognizable, Cornstalk appeared everywhere, first striking down a colonial then racing to bury his tomahawk in the skull of an Indian shirker. Colonial riflemen snapped shots at the Indian leader but without success. The struggle continued hour after hour with first one side rushing forward then the other. Warriors shouted, “Why don’t you whistle now?”, deriding the fifes that called the rifle companies to muster. The Virginians were somewhat in a trap, their backs to the rivers, but this also worked to their advantage. The anchored line precluded the Shawnee’s favored tactic of turning a flank and gaining their enemy’s rear.

Surprisingly, the allied warriors came on frontally in brave rushes led by their chiefs, Red Hawk, Blue Jacket, Black Hoof, Chiksikah, Cornstalk, and his son, Elinipisco. Fleming wrote: “Never did Indians stick closer to it, nor behave bolder.” The engagement lasted from an hour after sunrise to an hour before sunset. Captain James Ward fell, shot cleanly through the head, unaware that one of his sons, John, captured by the Shawnee at age three and renamed “White Wolf,” was firing his rifle with uncommon effect directly across the battle line.

Fierce Hand-to-Hand Combat Characterized the Morning

The river bottomland was filled with driftwood and rock outcroppings, and at about 1 o’clock in the afternoon a concerted push by the colonials gained a long ridge with logs and rocks that offered excellent cover. Slowly the Indians fell back to a second ridge that stretched from the Ohio to a swamp, and firing gradually slackened. As the ground fog lifted, the rifle fire of the colonials became more effective because their long rifles were decidedly superior. The fierce hand-to-hand combat that characterized the morning fight could be sustained for only so long, and the afternoon’s fighting slowed to long-range sniping. Still, emerging from cover could bring rapid death.

General Andrew Lewis, who had thus far not meddled with the largely individual fighting, in late afternoon decided to conduct a maneuver that could turn the battle in his favor. Coolly lighting his pipe, Lewis detailed Captains Isaac Shelby, George Matthews, and John Stuart to form their companies and find a way to flank the enemy line. The three young officers withdrew their men from the colonial line and led them on a circular route up the Kanawha, wading under cover of the riverbank. Turning up Crooked Creek, they emerged from the stream on a slight ridge in the enemy’s left rear and opened a scalding fire. This sudden assault shocked the Indian warriors.

Cornstalk was well aware from active scouts that Colonel William Christian was moving toward Point Pleasant with the remainder of the Fincastle Regiment. This flanking force was probably mistaken for that column, and Cornstalk began to withdraw his warriors. Cornstalk selected the best of his men to remain and continue the fight until all Indian wounded were carried across the Ohio. His brother, Silverheels, was wounded seriously and was conveyed back across the Ohio by their sister, Nonhelema, whose great size and strength had earned her the title Grenadier Squaw. Most of the Indian dead were committed to the river, and skillfully the Indian chief withdrew, retreating back into the forest across the Ohio.

When Christian’s regiment of Fincastle men arrived at about midnight they found the colonial camp in chaos. The wounded were suffering horribly, with only minimal medical assistance available. Fleming, the most noted surgeon, was so injured his survival was doubtful. The colonial soldiers tried fortifying their camp by constructing log breastworks, but many were so tired they simply fell asleep.

Casualties among the militia troops had been severe. A large number of the wounded were so badly injured there was little hope of their recovery. Eventually the casualty total would include 75 killed and 140 wounded, almost 20 percent of the force engaged. Charles Lewis and John Field would die of their injuries, while William Fleming would be disabled for life. Equally high were losses among the militia captains.

Casualties among the Indians are difficult to ascertain. Thirty-three bodies were recovered but many of the slain were carried from the field. Colonists felt the enemy loss at least equaled their own, but most sources feel Indian losses of 35 to 75 are more likely. There were no prisoners—the tenor of the colonial survivors can be measured by their bloodthirsty action in erecting a huge pole on the Ohio River bank adorned with 18 Indian scalps.

General Andrew Lewis buried his dead in long rows underneath the trees, where they lie to this day. Completion of the fortifications and care of the wounded occupied the army for several days. On October 17 Lewis crossed the Ohio, leaving a strong guard to protect the wounded. He advanced with his army, each man carrying 11/2 pounds of lead and four days’ rations, toward the Shawnee towns on the Scioto River, vengeance on the mind of each soldier. A messenger arrived as they neared the Scioto, informing Lewis that Dunmore was drawing up a treaty with the enemy and Lewis should advance no farther. Angry and frustrated, Lewis nonetheless disobeyed. He had lost a brother and among his soldiers many friends and kinsmen.

During the interval following the October 10 clash and Lewis’s crossing of the Ohio, Cornstalk accomplished much. He initially attempted to rally his followers to continue the fight. At council in Yellow Hawk’s Town on the Scioto he stated that “we must fight no matter how many may fall or we are undone.” But when he received no affirmation from his allies he realized that the Shawnee could not resist alone. Burying his tomahawk in the ground he angrily shouted: “Since you will not fight I go and make peace.” Wisely he saved his villages by opening negotiations with Dunmore at Camp Charlotte, which he established on the Pickaway Plains about 7 miles east of the Shawnee villages (25 miles from present-day Chilicothe, Ohio). So smoothly did he present his case that Dunmore, as noted, intercepted Lewis and ordered his men to countermarch. Cornstalk promised to surrender all white prisoners held by the assorted tribes and vowed that the Indians would desist in hunting south of the Ohio or harassing boats on the river. Dunmore followed with a promise that no more whites would enter Kentucky and that no settler should set foot north of the Ohio River.

At a formal little ceremony, Dunmore met Lewis’s officers and, shaking hands, complimented them profusely on their victory. But Lewis posted guards around the governor’s marquee because the mood of his soldiers was abusive toward Dunmore, several making direct threats. Reluctantly Lewis began a march back to Point Pleasant, arriving there on October 28. Dunmore made extravagant claims of saving the frontier that allocated little credit to Andrew Lewis and his men. But Lewis knew well how close the contest actually had been. He was aware that if the scales of victory had tipped to the enemy, he and each of his men would lie dead on the battlefield or be bound over as captives to grace the fires of the very villages he was forbidden to destroy.

The End of Dunmore’s War

Leaving Captain Arbuckle and 50 volunteers to garrison Fort Blair at Point Pleasant, Lewis dispatched his army by companies back to Camp Union. Officially the force was disbanded on November 4, 1774; Lord Dunmore’s little war was over. The governor received an extravagantly complimentary resolution from the Virginia House of Burgesses for his rapid redress of the Indian threat. But the controversy of his leadership and purpose was only beginning.

Many Virginia families suffered grievously from the brief campaign. Samuel Crawley of Pittsylvania County joined the Botetourt Regiment and marched off, never to return. His widow Elizabeth and her many children were consequently reduced to a life of poverty unassisted by pension or state compensation. Colonel Charles Lewis’s wife Rachael grieved so long and hard for her slain husband that many grew to believe her demented. Numbers of other seriously wounded Virginia frontiersmen would evermore depend on the care of their families. John McKenney, who had two bullet holes and a tomahawk blow to his back, would be an invalid for life. So, too, would William Fleming remain physically handicapped, although his active mind would gain him political employment. As details emerged and the ideological conflict with Great Britain grew imminent, Dunmore’s status among the populace of the state diminished rapidly amid extreme bias.

The Royal Governor’s actions in the Indian War were soon critiqued and questioned, even to the point of acclaiming that he had contrived to bring on the war for personal reasons. Many Virginians openly accused Lord Dunmore of duplicity in his dealings with the enemy. Colonel John Stuart, who marched with the force, avowed: “Dunmore acted as a party to British politicians who wished to incite an Indian War which might prevent or distract the Virginia colony from the growing grievances with England.” While the seriousness of that charge is evident, some went even further, positing that Dunmore had actually connived with or attempted to manipulate the Indians into annihilating Lewis and his army. This allegation, which Andrew Lewis came to believe, could have benefited Great Britain in its approaching conflict by stripping the Virginia frontier of defenders. But such a broad-based charge of contrived plotting seems to endow Lord Dunmore with skills of prognostication even beyond the scope of a Royal Governor.

A more likely accusation, made by Archibald Henderson in his “The Conquest of the Old Southwest” published in 1920, places Dunmore as party to a conspiracy with the nefarious Dr. John Connolly. The two reportedly initiated a complicated attempt to secure vast tracts of land from the Indians and to found an expansive colony in the area between the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers. This scheme resembled and rivaled Lord Dartmouth’s 1769 project of founding “Vandalia” in the American forests with a capital at the mouth of the Kanawha, a plan that may have been more con than reality.

While Dunmore surely coveted western acreage, so did George Washington, Patrick Henry, and even Andrew Lewis. Acquiring cheap western land was the surest route to power and prestige in America. Dunmore, like other royal appointees, was surely willing to use the patronage appointments attached to his office for that purpose. If he attempted to extend Virginia lands over the mountains and into the Ohio Valley as evidenced by his efforts to acquire Fort Pitt and its environs from Pennsylvania, could he and his associates not enjoy some personal advantage?

But Dunmore was never a commanding presence in the New World; at best he was a competent administrator in the British tradition. While influenced by the schemes of others, he persisted in upholding Virginia’s honor. When the revolution erupted, Dunmore’s zeal in seeking to retain the colony within His Majesty’s realm of influence earned the earl the burning hatred of his former subjects and every exaggeration of his prior motives.

A more realistic appraisal of Lord Dunmore’s talents perhaps can be ascertained by comparing his military and political exertions with those of the individual he consistently underestimated: Cornstalk. This handsome, charismatic war chief of the Shawnee maintained a diplomatic presence several paces ahead of his colonial adversary. Through an excellent cadre of scouts, Cornstalk shadowed each movement of both advancing colonial columns. The crafty Indian leader opened long-distance negotiations with Dunmore as the governor’s force moved downriver, while concurrently planning the isolation and destruction of Lewis’s column at the rendezvous point. It can be postulated that Cornstalk’s messages to Dunmore were merely premeditated ruses by the Indian leader to delay, stall, and pacify Dunmore with promises of peace while he destroyed Lewis. If Lewis and his men were removed from the military chessboard, Cornstalk could possibly bluff, intimidate, or defeat the inexperienced Dunmore.

Fearless in combat, Cornstalk almost carried off the military victory, for in truth his advancing forces were discovered by accident. When Lewis’s army narrowly survived, and Cornstalk’s allies deserted, the war chief journeyed to Dunmore and reopened his overtures, settling for a favorable peace before Lewis’s revengeful column could unite with the governor. Dunmore only once caught a glimpse of Cornstalk’s range of character, intellect, and ability. As he later discussed the agreement of Camp Charlotte, Dunmore conceded, “I have heard the first orators of Virginia … but never heard one whose powers of delivery surpassed those of Cornstalk on that occasion.”

As anticipated, little attention was accorded to the agreement between Dunmore and Cornstalk. The Ohio River Valley was soon flooded with settlers. In March 1775, Richard Henderson and his company purchased most of modern Kentucky from the Cherokee at the Sycamore Shoals Council, despite vehement objections from a rising young Cherokee chief called Dragging Canoe. Henderson and his friends organized the State of Transylvania in May of 1775 amid opposition by the Cherokee, English, Virginians, and North Carolinians. Transylvania soon disappeared when all of Kentucky became a Virginia county, but Henderson and his cohorts were well compensated with land grants of almost 400,000 acres.

The Struggle to Control Ohio was Long and Violent

The brief little war that history would label “Lord Dunmore’s War” was but a chapter in the violent struggle to control the Ohio. From the close of the French and Indian War in 1763 until Anthony Wayne’s victory at Fallen Timbers in 1794 the cruel, violent clash of cultures persisted. The last bastion, the final line of defense for the eastern Indian tribes, was the Ohio. Both whites and Natives believed their cause was right and as warfare persisted they both came to believe that continued existence of the other threatened their future. The colonist’s obsession with land, to be held and passed on in perpetuity, gave them the individual freedom and self-determination they so avidly desired. But this fundamental concept could never be understood as anything but avarice by an Indian culture to which land, streams, and rivers were a communal possession. War, disease, and settlement—the three horsemen of the Indian apocalypse—gradually pushed the Indian population toward extinction.

Dunmore’s War quieted the ongoing conflict between Indians and colonials, at least for several years. It was 1777, three years later, before Indian tribes began to ally themselves with the British, who replaced the French in the forts along the Great Lakes. This interlude freed the experienced frontiersmen of Virginia, unencumbered by the constant threat of Indian attack, to provide leadership and spirit to the American Revolutionary Army. The victory of Lewis’s small army was the first purely American military effort undertaken and executed totally by frontier militia—a valuable prognosticator for military organization in the colonies. This signal success also provided a window of time for the settlement of Kentucky by Boone, Kenton, Wetzel, and many other unique American woodsmen. But the peaceful interval was only a lull in the war of extermination. Despite the horrifying total defeats of American expeditions under Colonel William Crawford in 1782, General Josiah Harmar in 1790, and General Arthur St. Clair in 1791, frontiersmen persisted in pushing the line of settlement west. Ultimately Maj. Gen. Anthony Wayne would destroy the fighting power of the tribes at Fallen Timbers on August 20, 1794.

Dunmore returned to Williamsburg and Lewis to his role as protector of the Virginia frontier. Their philosophical differences were put aside for a time, but the two men would meet again as bitter antagonists.

Lord Dunmore, true to his king and country, bitterly resisted the revolutionary movement in Virginia. Forced to abandon his Williamsburg Governor’s Mansion on June 7, 1775, he fled to HMS Fowey at Yorktown and for some time attempted to rule from the quarterdeck, offering freedom to all slaves and bound-men that would join his cause. In May of 1776 Dunmore moved his base to Gywnn’s Island, off the Virginia Northern Neck. Brigiadier General Andrew Lewis commanded an American force that opened a tremendous bombardment from masked batteries on Dunmore’s ships and camps on July 8, 1776. Lewis himself fired the first cannonball from an 18-pound smoothbore, which holed HMS Dunmore. Forced to abandon Gywnn’s Island, Dunmore anchored near St. George’s Island in the mouth of the Potomac River, a popular watering site, and finally, on August 6, 1776, Dunmore sailed past the Virigina Capes for England.

Cornstalk returned to his role as chief of the Shawnee. Despite his bloody past he refused to deviate from the path of peace once he gave his oath, even resisting English entreaties. In a final attempt to maintain peace he would meet a tragic end.

In the fall of 1777, Cornstalk and two other Indians traveled to Point Pleasant to inform Captain Arbuckle, commander at Fort Randolph (which replaced Fort Blair), that Indian lands north and west of the Ohio were rapidly being settled by colonists in violation of his agreement with Lord Dunmore. Arbuckle placed the Indian envoys under arrest and sent for his commanding officer. Well treated, Cornstalk was irked over the confinement but remained calm and serene. On November 9, a young white hunter was slain by Indians across the Kanawha. An angry mob of colonials, sparked by the murder and vowing revenge, charged the gates, brushing aside Captain Arbuckle. Breaking open the door of the jail, they fired a volley into the three imprisoned Indians. Seven musket balls struck Cornstalk, killing him instantly. It was an inglorious and tragic fate for such a brave, courageous, and noble chief who had been on a mission of peace.

At Tu-Endie-Wei Park (Shawnee name for mingling of the waters) near the bridge to Gallipolis, Ohio, lie the dead of Point Pleasant. For nearly 70 years they lay in silence and neglect, despite their valor and sacrifice. They rest now in long rows beneath a bronze tablet recording their names. A statue of a Virginia frontier rifleman guards their final bivouac. Close by in a single grave rest the remains of the Indian warrior and statesman Cornstalk. Near these gravesites rises an 84-foot granite shaft, the tallest battle monument west of the Alleghenies, honoring a battle stoutly contested and long forgotten. The coming revolutionary conflict, with its wide-reaching implications, swallowed the survivors of Point Pleasant, and the scope and ferocity of revolutionary warfare overshadowed the sacrifice of the men who fought and died there. An often-repeated old mountain ballad describes the feelings of the few that remembered.

As Israel mourned and her daughters did weep, / For Saul and his hosts on the mount of Gilbo /Virginia will mourn for her heroes, who sleep / In her tombs on the bank of the O—hi—O.

my 10th great grandfather fought in this battle and even named his son pleasant who settled in missouri

I read the story of Cornstalk in differant books and they all give a differeant story

My ancestor Capt John Skidmore had a company of men that fought in the battle and he was one of the wounded, his name is on the monument at the national park in Point Pleasant.

My 6th Great Grandfather, Captain Samuel Wilson of the Augusta militia was killed at the battle of Point Pleasant and is buried on the site along with the other Officers who died that day.

Excellent account of the battle at Point Pleasant. Well rendered factual evidence and thoughtful insights into the situation of the day. I especially appreciate you presenting different perspectives, letting the reader follow a path of thoughtful review. Very well done and I’m a fan. dml

My 6th Great Grandfather, Captain Samuel Wilson of the Augusta County militia was killed at the battle of Point Pleasant.

Myself and a few other Members of the General Adam Stephen Chapter of the Sons of the American Revolution (SAR) will be attending the October events at Point Pleasant and it will be an Honor to stand at attention where my ancestor fought and gave his life.

In his epic masterpiece , The Frontierman, Allen Eckert gave an account of this fierce battle, however this article goes into far greater detail about the main characters involved, as well the aftermath of the battle. Very well done. My family’s roots go back to southern Ohio, and the land along the Ohio.

I plan attending the 2024 event, which will be 250 years.