By John Murphy, Jr.

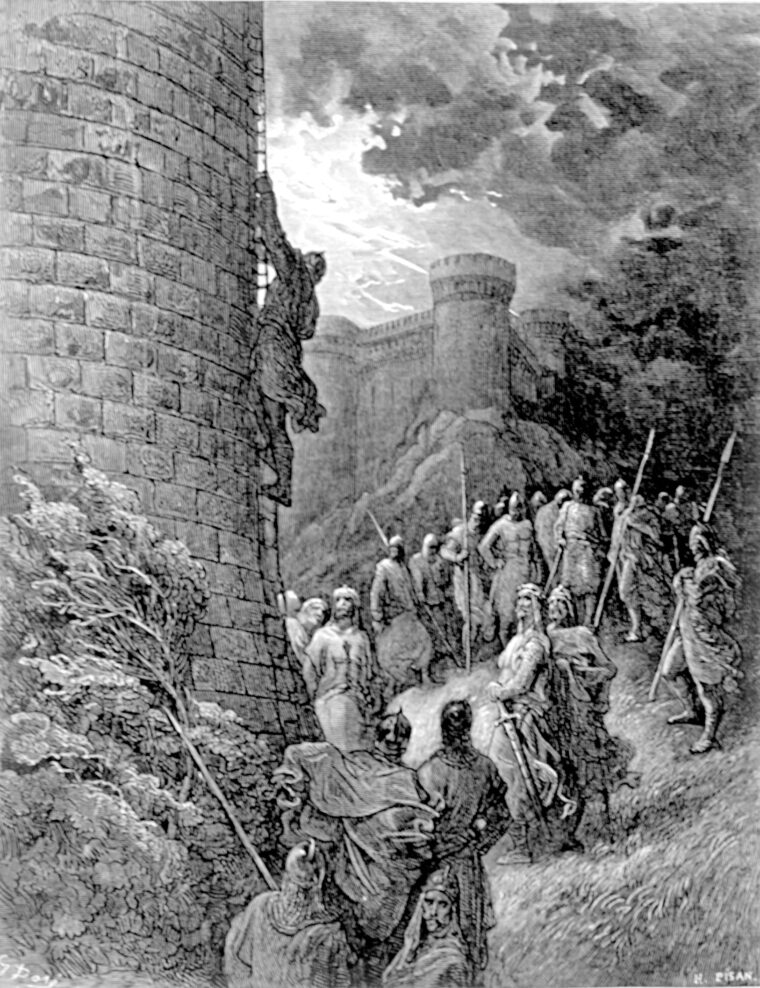

Shortly before dawn on June 3, 1098, Bohemund of Taranto, one of the leaders of the First Crusade and the survivor of many campaigns, stood in the shadow of the Tower of the Two Sisters, one of the strongest points in the defenses of the ancient city of Antioch. Bohemund had with him 60 veteran swordsmen, because this special operation was no place for novices in the bloody art of killing. Fortunately, the moon was only in its first quarter, so the little light available was provided by the torches along the battlements of the city walls. Thus the city’s Seljuq Turk commander, or pasha, Yagi Siyan, could not well discern the night’s events.

The day before, Bohemund and the other leaders of the Crusade—Godfrey of Bouillon, Bishop Adhemar de Puy, Count Raymond of Toulouse, Hugh of Vermandois, and Count Robert of Flanders—had sent a large party of mounted knights and men-at-arms on a razzia, or raid, to the southwest of the city. If Yagi Siyan or any of his commanders, or emirs, had seen this they would not have been surprised. The Seljuqs would have assumed that the Crusaders had gone on another foraging expedition to garner food for the soldiers and their camp followers and provisions for their oxen and horses.

The Crusaders had been camped below Antioch’s impregnable walls since October 21 the year before. But the conditions were deplorable. Even Yagi knew that sickness and starvation were decimating the Crusader ranks. Yagi also knew that somewhere out in the east in the Syrian Desert was his salvation. Karbuqa, the Seljuq sultan of Baghdad, city of the Arabian Nights, was on his way to relieve him and Antioch with a huge army, or jund, of some 200,000 men. When the war drums mounted on camels heralded Karbuqa’s arrival, all Yagi would have to do was charge out of Antioch’s Bridge Gate, the one nearest the Crusaders’ camp, and crush them between his force and Karbuqa’s army.

The Harsh Fate of the Crusaders

Those Crusaders who were not slaughtered would be sold into slavery. The pretty women would go to the harems of Yagi, Karbuqa, and their emirs, or be sold in the slave markets of Antioch, Damascus, or Baghdad. The young men would face a grimmer fate. Some of them would be sold as slaves and then castrated to serve as eunuchs in the Seljuq courts. Those who did not become eunuchs, or who were not rich enough to afford their ransom, would die as slaves for their Muslim overlords.

But Yagi did not know that after dark on the night of June 7 the Crusaders’ horsemen returned from their razzia, which had only been a feint to distract his attention if indeed he had seen it in the dim light. The Crusaders in the camp had spent the night preparing for what they knew would be their decisive battle. When—or if—the mighty war horn of Lord Bohemund sounded, they would be ready to strike.

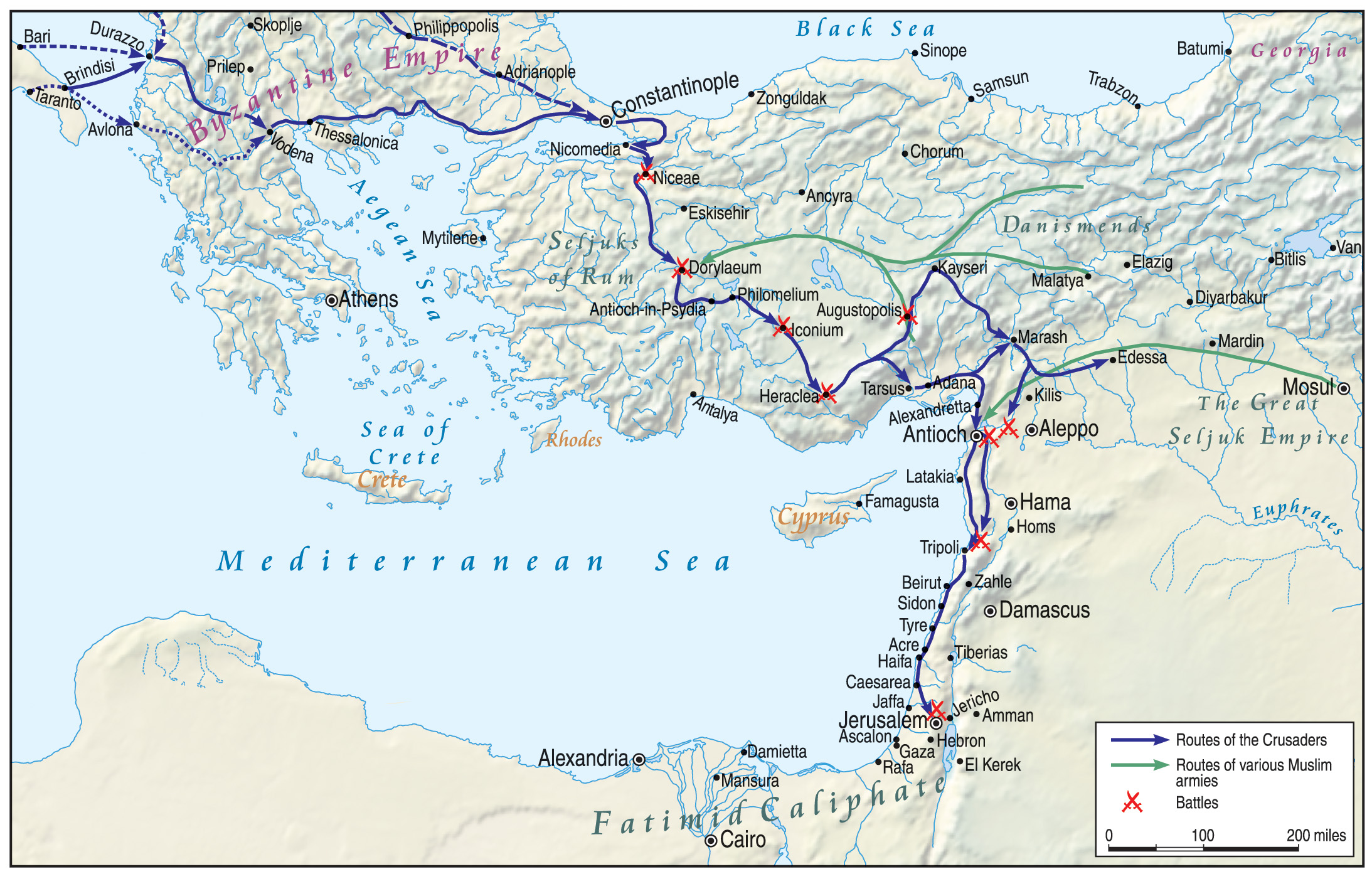

Much had happened since the day in October when the Crusaders had their first glimpse of Antioch—now Antakya—on the Orontes River in present-day Syria. For centuries, Antioch had been the gateway to the Mediterranean Plain. Historians believe that the Persian “King of Kings” Darius had marched from the city, then known as Sochi, to his crushing defeat by Alexander the Great at the Battle of Issus in 333 bc. The Crusaders were excited when they first saw Antioch, for they knew it was the last major obstacle on their path to Jerusalem, which Pope Urban II had preached the First Crusade to save from the Seljuq Turks. The chronicler of the Crusade, who has come down to us simply as “The Unknown,” wrote: “And so finally our knights reached the valley where Antioch, the royal city, is situated, which is the head of all Syria, which once the Lord Jesus gave over to the blessed Peter.”

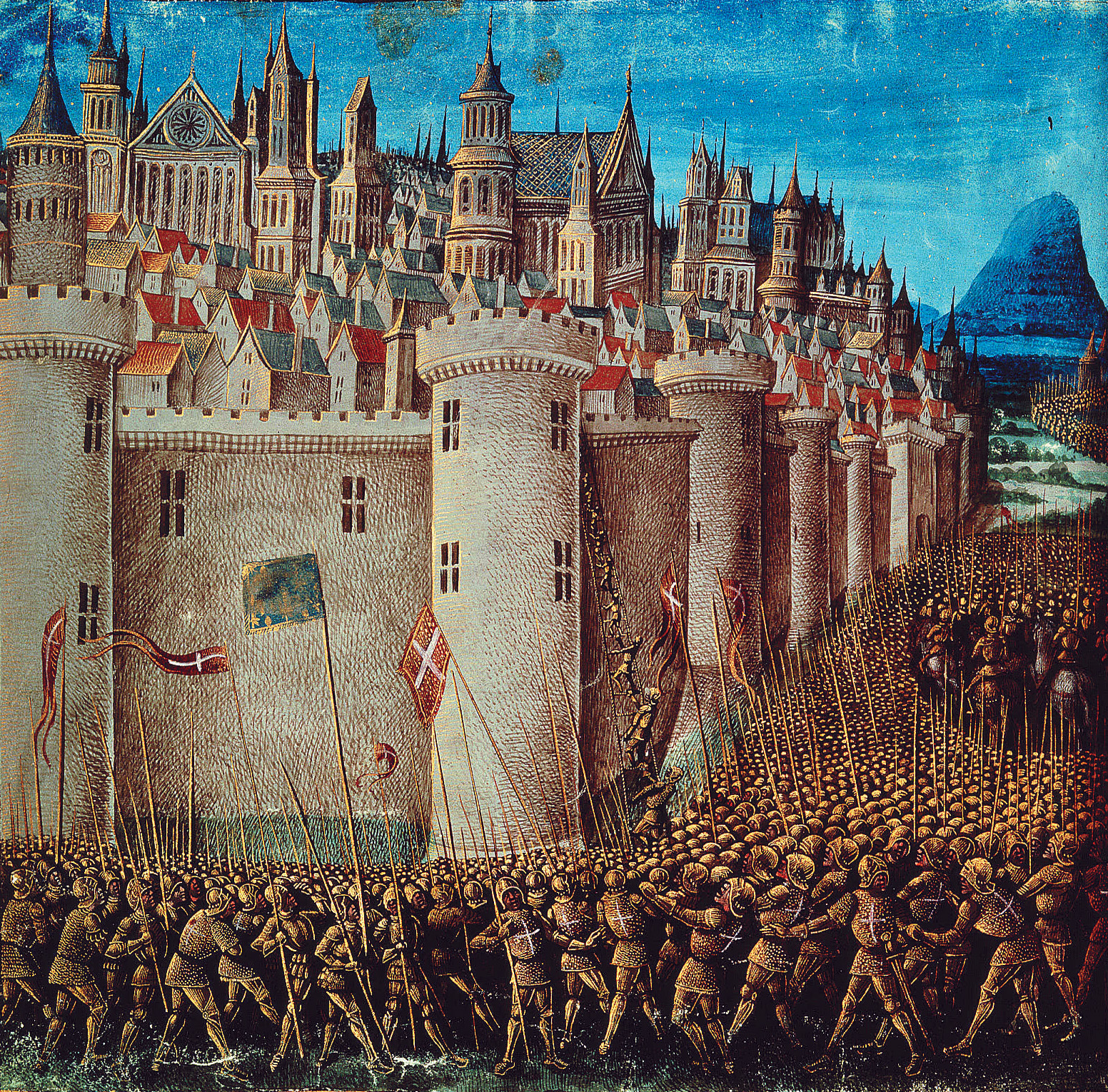

The ardor of the Crusaders dimmed when they realized how strong Antioch’s defenses were. The city’s fortification was initiated by civilizations as early as the Romans, and reinforced by the Byzantines and the Arabs. Antioch’s walls were now some 30 feet high and broad enough for four horses to ride abreast around the top of their ramparts. The walls extended for miles; topping them was the huge citadel which, even if the city fell, would allow Antioch’s defenders to hold out indefinitely. The citadel could not have been built on a better site. In the summer of 1909, Lawrence of Arabia (Thomas Edward Lawrence) had visited Antioch while a student at England’s Oxford University. He noted in Crusader Castles that “the castle [the citadel]” was “on a mountain peak and very hard to get at.” Even worse for the Crusaders, Antioch was full of gardens and pastures, which would provide plentiful food for its people and livestock until help could arrive from the Seljuq Turks. When Stephen of Blois, one of the minor chieftains of the Crusade, wrote home to his wife Adele, he was not exaggerating when he said that Antioch was “the strongest and most impregnable [city] we have come upon.”

A Council of War

Faced with the hopeless task of surrounding or laying siege to the entire city, the leaders held a council of war. They decided to invest the three northern gates of Antioch which were nearest to them. Then the chiefs sent foragers out to scour the Syrian countryside to gather as many provisions as possible to support the crusading army during the siege that lay ahead. What could not be gathered would have to be purchased (no doubt at inflated prices) from the Syrian and Armenian merchants who might sell to them despite Seljuq reprisals. At least the Crusaders knew that the Armenians were on their side, because the nearby Christian Armenian Kingdom of Cilicia was still holding out against the Turks. (In 301 ad, under King Trdat III, Armenia was the first kingdom in the world to embrace Christianity.)

Inevitably, whenever the Crusaders sent out a large foraging party, Yagi would send out his own cavalry to thwart them. The reasons were simple. If he could stop the Crusaders from obtaining necessary supplies, famine would wipe them out and save him a bloody contest of arms such as had bloodied the Seljuqs at Dorylaeum. The Crusaders tended to march in separate contingents, each under its own commander. On June 30, 1097, the pasha of Nicea, Kilij Arslan (the Red Lion), had surprised the Crusaders under Bohemund while they were in camp. For over six hours, Bohemund’s division, from knights to cooks, withstood Kilij’s assault. Then, just when the Turks thought the Crusaders were finished, the rest of the crusading army, their gonfanons (battle flags) snapping in the wind, tore into Kilij’s army from the rear. The effect was overwhelming—the Seljuqs broke and ran. The writer of the history of the Crusade called the Gesta Francorum, “Deeds of the Franks” (all Crusaders were called “Franks” because most were French), related that “we pursued and slew them the whole day long. And we got much spoil; gold and silver, camels and sheep and oxen, and many other things.”

Yet by the end of November 1098, winter was coming and there was no sign of Karbuqa of Mosul. Snow soon would cover the mountain peaks and the soldiers on guard at night would huddle in the cold. Even worse, to Yagi’s stupefaction, the Crusaders had almost surrounded the entire city, in spite of its size. During November, a fleet from Genoa had brought reinforcements for the Crusade, and these new arrivals had helped the chiefs tighten the noose around Yagi’s neck. They had even succeeded in throwing a bridge over the Orontes River in front of the town to hem Antioch in completely. The spoiling raids Yagi sent out to disrupt the progress of the siege had been brushed aside by the more heavily armed European knights. Clearly, it was necessary for the pasha to do something more because the amount of food inside the town was finite and the Crusaders were isolating Antioch from getting supplies outside its walls.

The Riderless Horse

Then the pasha saw an opportunity and rapidly took advantage of it. One day Bohemund led off a huge party of some 20,000 men on a razzia, leaving behind a weakened force. Quickly, Yagi threw open the Bridge Gate and his horsemen clattered over it into the Crusaders’ camp. The attack fell on the section of the camp defended by Count Raymond, Lord of Toulouse, whose region was in Provence, in the south of France. The Provençals stood their ground until, in one of those instances that can change the course of a battle in the blink of an eye, they became frightened by a riderless horse. All of a sudden, the Provençals buckled, giving the Turks the chance to push home their attack. But then, as at Dorylaeum, the Crusaders’ sophisticated command system saved them again. Once more a counterattack, led this time by Godfrey, Adhemar, and Raymond himself, repelled the Turks and physically forced them back over the bridge into the city walls.

It was this type of engagement the Turks feared, and which they invariably lost with heavy casualties. As with other Central Asian invaders who had ridden westward since the time of Attila and his Huns in the 5th century, the Turks were accomplished horse archers. They would ride up to their enemy time and again, letting loose hundreds of arrows in the hopes of gradually wearing down their opponents. But Bohemund—according to R.C. Smail in his Crusading Warfare, 1097-1193—had developed tactics to defeat them. He had trained the foot soldiers and camp followers to fight like a trained army.

Unlike other European commanders of his age, Bohemund realized that it was the foot soldiers of the “common folk” who could stand their ground against the mounted attacks of the Turkish archers. He kept his mounted knights and men-at-arms in reserve until the order came to charge. Then, looking like human porcupines with the shafts of the arrows standing out from their kite shields and chain mail, the knights would hurl themselves upon the Turkish horsemen. Then the slaughtering would begin with their heavy swords and war axes.

In addition to the Crusaders’ prowess with their weapons, their horses (called destriers or chargers) were living weapons on four legs. The fine Arabian stallion was no match for the Western European horse, the ancestor of the Percheron, from today’s Perche region of France. The Arabian stands at about 14.3 hands high, or roughly 59 inches. The Percheron, however, is over 16.2 hands high, or some 64 inches. Indeed, the Percheron is so much bigger than the Arabian that it actually has an extra rib—18 in a Percheron instead of the Arabian’s 17. Thus, in single combat it was possible for the European knight, a taller man on a larger horse, to push over a Turk on his smaller mount and crush him under his charger’s hooves. In one such engagement, Bohemund led a charge that killed some 12 emirs and 1,500 Turks. Once again, he harried the enemy back to the Bridge Gate, “driving and hurling them into the river, so that the waters of the rushing stream seemed all red with Turkish blood…. Only the night brought an end to the conflict.”

The Cannibalistic Tafurs

Yet, with the coming of winter, it was becoming a grim game to see who would crumple first—the besieging Crusaders or the hard-pressed Turks. In spite of efforts by the Byzantine fleet to supply the Crusaders by sea, the situation in the camp had become desperate. The Armenian and Syrian merchants raised the price of food so high that much of the army could not afford to pay. Pitifully, they died of starvation. “The Unknown” mourned, “Thus died many of our men who were not able to pay such prices.” With their penchant for settling things by force, it remains one of the mysteries of the First Crusade why its leaders did not simply seize the merchants’ supplies and put to the sword those who held them back.

There was one group, however, that never went without food. Peter the Hermit had led a ragged contingent to the Holy Land before the knights could muster in Europe. He had reached Byzantium (Constantinople), the capital of the Byzantine Empire, in July 1096. The Crusaders, being professional soldiers, had taken longer to prepare and had not reached Byzantium until April 1097. Among those who had survived with Peter was the group known as the Tafurs. According to L.A.M. Sumberg, in the journal Medieval Studies, the Tafurs “always fought in the front line and made the most of any Turks they killed”—they ate them!

Inside the city, conditions were also critical. So much so that Yagi Siyan sent his own son, Shams al-Dawla, “the Sun of the State,” to bring help from two feuding brothers. These were Ridwan of Aleppo and his brother Duqaq, who ruled in Damascus. Ultimately the intrepid Shams prevailed on Duqaq to march to save Shams’ father Yagi. Duqaq finally left Damascus for Antioch in December 1097. On December 31, as Bohemund and Robert led a massive razzia to the south, they met up with Duqaq coming north at al-Bara.

In a classic “encounter battle,” the two sides immediately threw themselves at each other. Duqaq relied on the tried tactics of the horse bowmen of the Central Asian steppes and attempted to encircle the Crusaders and whittle them down with barrages of arrows from the Seljuqs’ bows. This system had worked against European armies since the ancient Parthians used it to decimate the Roman army of Crassus at Carrhae in 55 bc. But the Crusaders knew the tactic. The Seljuqs came on in the same old way, and the Crusaders crushed them in the same old way. When the signal was given, Robert of Flanders led a cavalry charge that broke through Duqaq’s force. Not only did Duqaq hurriedly retreat south to Damascus, but the victorious Bohemund and Robert were also able to return to the encampment with all the cattle and other booty they had been able to gather.

Ridwan’s Folly

By early February of the new year, Ridwan finally advanced from Aleppo. Over the winter, the conditions in the Crusader camp had grown worse. In addition, at this time they suffered a blow in strength when General Tacticius, who commanded the Byzantine contingent, chose to leave the Crusader ranks. Zoe Oldenbourg in her account says that Bohemund made up a story about a conspiracy against Tacticius by the other crusading leaders as a way to rid themselves of the Byzantine, whom they had never trusted anyway. Nevertheless, it was a foolish move, because the Byzantines had provided many of the skilled engineers who were important assets during a siege. Furthermore, with their Pecheneg allies, the Byzantines had skilled horse archers who could have helped keep the enemy away from the camp.

When Ridwan—who will never be ranked as one of the world’s military geniuses—arrived, he made camp instead of throwing his thousands of fresh horsemen at the famished Crusaders. Incredibly, he chose a site on a narrow spit of land between Lake Antioch and the Orontes River, which he felt was a strong defensive position. But he was ignorant of the bride of boats, a medieval version of the pontoon bridge, which the Crusaders had laid across the river. On February 8, the Crusaders convened to decide how to meet the new threat before Ridwan could act. Only about 800 men were now able to ride, so Bohemund proposed that the foot soldiers stay behind to guard the camp and the remaining horsemen set out at night to take Ridwan by surprise.

At dawn, the Turks in Ridwan’s camp awoke to the Crusaders’ battle cry, “Deus le veult!” (God wills it!) and the blaring of war horns. The narrowness of the battlefield made it impossible for the Aleppans to use their bows. Any arrows shot within such a close perimeter had as much a chance of striking a Turk as a “Franj,” the Turkish name for the Franks.

With Ridwan were ghulams, the heavy cavalry of the Seljuqs. The Turks always hoped the ghulams would be their answer to the armored warriors from Europe. But the larger size of the mounted Crusaders and their better training won the day. Once among the Aleppo force, the swords and axes of the Crusaders rose and fell in the brightening morning with lethal regularity, each blow able to shear through a steel helmet and the Turk who wore it.

From the walls of the city, Yagi was unable to see how the densely packed combat was going. Thinking Ridwan was winning, he sent out a mounted force to catch the Crusaders in the rear, hoping to pin them between the city walls and the Aleppans. But before they could reach the battle, Ridwan and his men gave way and fled. Yagi then engaged the foot soldiers defending the camp, who held him while the horsemen finished off the Aleppans. When the mounted squadrons of the knights and men-at-arms, fresh from bloodying Ridwan, smashed into Yagi’s men, the shock was too great. The riders from Antioch turned their horses about quickly and fled into the safety of the high walls. But for some there had been no escape. That night, Antioch’s defenders witnessed the grim spectacle of the Crusaders’ catapults throwing the severed heads of their dead comrades into the city.

“The Franj Were Seized With Fear”

For a few weeks, the tide of battle seemed to turn in the Crusaders’ favor. By March, in what must rank as one of the greatest feats of military engineering, the determined Crusaders finally managed to block in all of Antioch. Then, in May, word was received from spies, probably from among the Armenians, that Karbuqa had finally mustered his huge field army and was leading it to Antioch. Ibn al-Athir, one of the Arab historians of the Crusade, remembered that “the Franj were seized with fear when they heard that the army of Karbuqa was on its way to Antioch, for they were vastly weakened and their supplies were slender.”

But then occurred one of those events that suddenly shift the fortunes of war. On the way to Antioch, Karbuqa decided to take the rich city of Edessa, which Baldwin, the brother of Godfrey of Bouillon, had earlier gone off to conquer for himself instead of proceeding to Antioch. For three weeks in May, Karbuqa tried in vain to batter his way into Edessa.

Meanwhile, conspiracy was afoot inside the city walls. Yagi Siyan and his chief vizier, an Armenian named Firuz, had had a falling out. However their relationship may have been when they first met, we know from the eyewitness chroniclers of the First Crusade that by this time it had grown stormy. Likely, Yagi Siyan, who had the mentality of a conqueror, looked down with contempt upon those his sword had broken. This would have included people of Firuz’s ilk from the Kingdom of Cilicia, a remnant of a larger Armenian kingdom that the Turks had destroyed. Furthermore, to have become the vizier in the Seljuq “new world order,” Firuz most likely would have had to renounce his Christianity. To a man of Yagi’s temperament, this would only have added to his contempt for Firuz. On top of this, Yagi discovered that Firuz may have been speculating on the black market in food during the siege—and even smuggled out provisions to the Crusaders.

In a frothing rage, Yagi threatened Firuz’s life and the lives of his family. Firuz knew of the savagery of the Seljuq’s punishments, and may have feared he and his family would be crucified like Christ. So he hit upon the desperate gambit of making contact with the besieging knights. If the leaders of the crusade promised to spare him and his family, he would let them into the city. Some accounts say he sent his brave young son to Bohemund with the plan. Knowing of the eventual coming of Karbuqa, Bohemund immediately accepted the offer.

Thus it was that in the early dawn of June 3, Bohemund and his 60 men stood beneath the Tower of the Two Sisters, not knowing if Firuz or the Turks were waiting for them. This was not their only concern. On the previous day, Stephen of Blois, upon learning of the approaching Karbuqa, had decamped for the north with his contingent of northern French, abandoning his fellow Crusaders. The contingent of Westerners around Antioch was smaller than ever.

Deus le Veult!

Suddenly a rope ladder was lowered from the parapet atop the tower. Immediately, Bohemund seized it and began the dangerous climb. William of Tyre wrote later that Firuz apparently let the ladder down personally to the Crusaders, and that Bohemund was the first to climb it. Al-Athir wrote that the Franks “climbed to that small window, opened it, and hauled up many men by means of ropes. When more than five hundred of them had ascended, they sounded the dawn trumpet while the defenders were still exhausted from their long hours of watchfulness.” Bohemund and the other warriors roared out, “Deus le veult!” and began to fight their way to the Bridge Gate and the Gate of St. George.

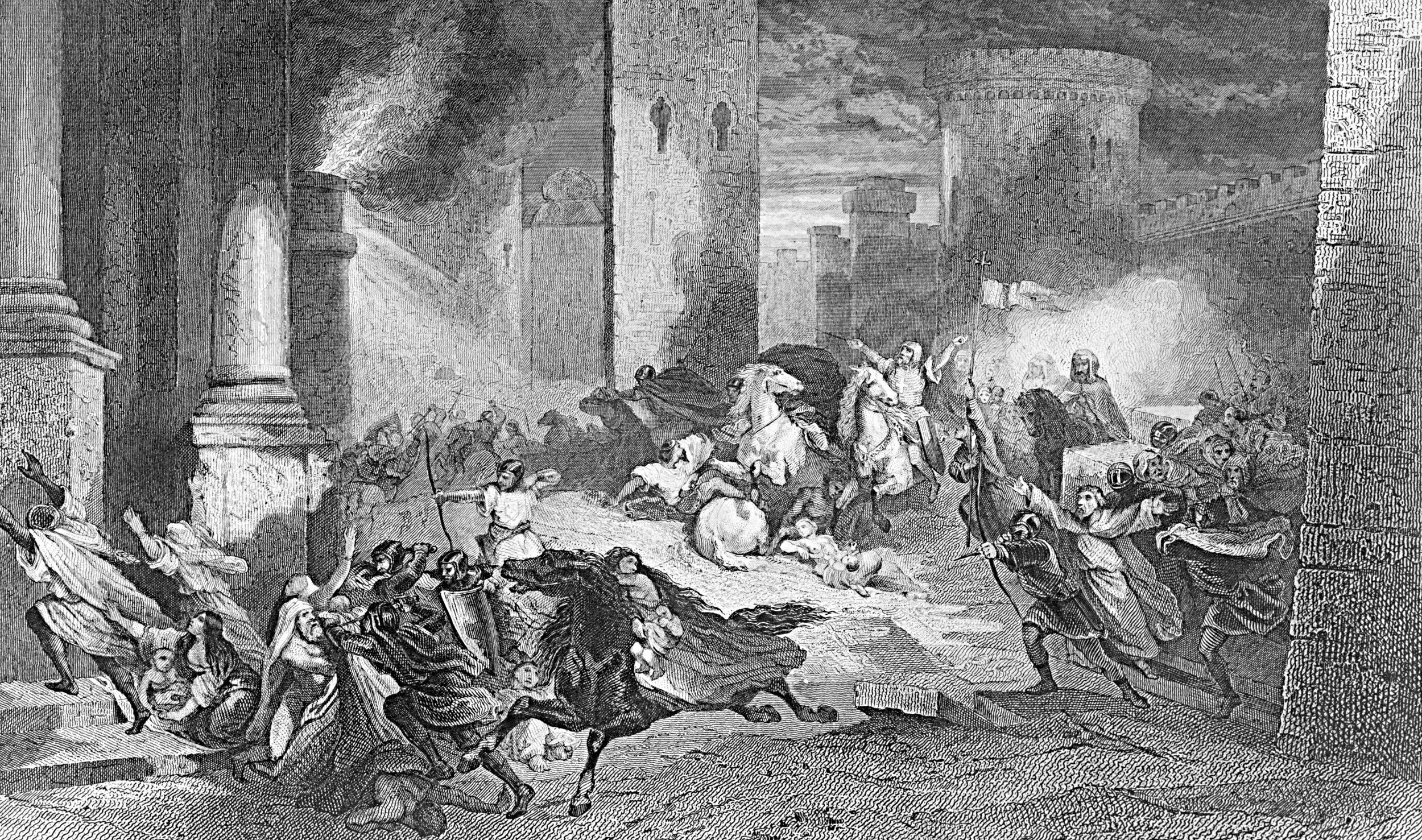

Meanwhile, the Crusaders in camp heard Bohemund’s trumpet and scurried into action. They raced to the gates, now flung open by Bohemund and his invaders. Soon the entire army was pouring into the surprised city, slashing down any Turks in their way. Yagi, seized with sudden panic, rode off with his bodyguard to leave his soldiers to their fate. So long defied by Antioch’s defenders, the Crusaders now surrendered themselves to a furious blood lust. Neither soldier nor civilian was spared. The Muslims who took refuge in the Jami mosque were all put to the sword. By dawn, the gonfanons of the nobles hung over the ramparts of the conquered city.

Only the citadel, rising out of the city walls on its tall hill, still resisted. It was defended by Shams who, in Antioch’s most desperate hour, had proved a braver man than his father. The citadel was a tough fortification, and rather than attempting to storm it, Bohemund circled it hoping to starve out Shams and the other defenders, or later to negotiate their surrender.

There was no such hope for Yagi, however. A little later, a party of Armenians came riding to Antioch to present two gifts to the mighty Bohemund: Yagi’s sword—and his head.

Two days later, on June 5, the Crusaders saw Karbuqa of Mosul’s huge army arrive on the plain before the city. Duqaq rode with him, like a jackal looking for his share of the spoils. But the three weeks lost attempting to gain the spoils of Edessa had cost the ruler of Mosul dearly. Now the city was in the hands of the enemy—and it was he who would have to dislodge them. Karbuqa reached the citadel, where he removed Shams and placed his own man, Ahmed ibn Merwan, in command.

Immediately, Karbuqa gambled on the shock of his arrival. On June 9, hoping to take the city by storm, he launched an offensive all along the line of the Orontes. But the Crusaders were not deterred. The main thrust of Karbuqa’s attack, led by Merwan, was on a redoubt known as the Blessed Mary. The Frankish defenders, most likely commanded by Robert of Flanders and Hugh of Vermandois, once again showed their superiority in close combat. After some bitter hand-to-hand fighting, Merwan and his attackers retreated. But it was obvious the Crusaders outside the walls could not withstand Karbuqa’s army, reinforced as it was by the defenders of the citadel. All outworks, including the Blessed Mary, were put to the torch to deny their use to the Turks.

Cowardice and Treachery

Before Karbuqa could complete his investment of the city, the Christians made a sortie out of the Bridge Gate but were fiercely repulsed. By June 11, the besiegers were the besieged. Any Crusaders who attempted to seek refuge with the Genoese at anchor in the harbor of St. Simeon were cut down by riders Karbuqa had deployed just for this purpose.

Worse yet, in an attempt to cover up his cowardice with an act of treachery, Stephen of Blois met up with a large relieving army led by the Byzantine Emperor Alexius Comnenus. When asked how fared the Crusaders in Antioch, he told the Emperor that the city had most likely fallen to Karbuqa. Fearful of being surprised by Karbuqa’s conquering army, Alexius turned about and retired to Byzantium.

Karbuqa’s arrival had come too close upon the taking of the city for the Crusaders to lay in supplies to withstand his siege. Thus the specter of starvation entered Antioch with them from their camp. Soon the proud knights were forced to butcher their beloved chargers for food. Father Raymond of Aguilers, a chaplain with the Provencal troops of Count Raymond of Toulouse, noted in a matter-of-fact way, “The head of a horse without the tongue sold for two or three silver shillings, and the intestines of a goat, in truth, for five.” Al-Athir, apparently receiving information from inside, noted that “the nobles devoured their mounts, the poor ate carrion and leaves.” (The Arab apparently did not know what kept the Tafurs, the cannibal followers of Peter the Hermit, alive.) It appeared that starvation, after all these months, might win where Turkish swords could not.

Then a strange event occurred that even the passage of 900 years has not explained with satisfaction. On the evening of June 10, a peasant named Peter Bartholemew came to request an audience with Bishop Adhemar and Raymond of Toulouse, then a sickly man who had given over command of his troops to Bohemund. Peter told the two leaders that the Apostle Andrew had told him that in Antioch’s St. Peter’s Cathedral, which the Turks had been using as a mosque, lay buried one of the holiest relics of Christendom: the head of the lance the Roman centurion Longinus had thrust into Christ’s side as he was on the cross. Father Raymond was there and he recorded that Bartholemew said that St. Andrew had told him in his vision, “Come and I will show you the lance of our Lord Jesus Christ, which thou wilt give to the count [of Toulouse], since God hath intended it for him since birth.”

“At Last the Lord Was Moved to Pity Us, and Revealed to Us His Lance”

Peter then told how the saint had escorted him into the cathedral. There, Andrew had held up the lance head, declaring “Behold the lance which opened the side of Him from Whom hath come the salvation of the world.” Although Adhemar was skeptical, Raymond, in spite of his sickness, took 11 of his trusted followers with Peter to the cathedral the next day. All day long, the Provençals dug a deep pit in the floor. Finally, all departed in despair except for Peter and the chaplain Raymond, and some onlookers. In desperation, Peter “went down into the pit wearing only his shirt. He implored us solemnly to offer prayers to God…. At last the Lord was moved to pity us, and revealed to us His lance.” Raymond himself clambered down into the hole and “when no more than the point had appeared above the ground—I kissed it.”

Whatever we may think of such a tale nine centuries later, word that the Lance of Christ had been found spread like an electric current throughout the camp. The joyous people sang, “Wood of the cross, sign of the leader, follows the army never yielding, always advancing, borne on by the Holy Spirit.” Sick and well, rich and poor were seized with a religious zeal not seen since Pope Urban II had first preached the Crusade. But the leaders lacked the faith of their followers; they hesitated to take on Karbuqa’s huge force. In fact, Raymond and the others sent a secret messenger to Karbuqa asking for terms of surrender. The message was carried on June 27 to Karbuqa’s tent by Peter the Hermit. Sensing victory, Karbuqa refused the terms of surrender. He declared that that the Crusaders could become Muslims, “but if they do not do this, they will die or be kept slaves to serve us.” The die was cast.

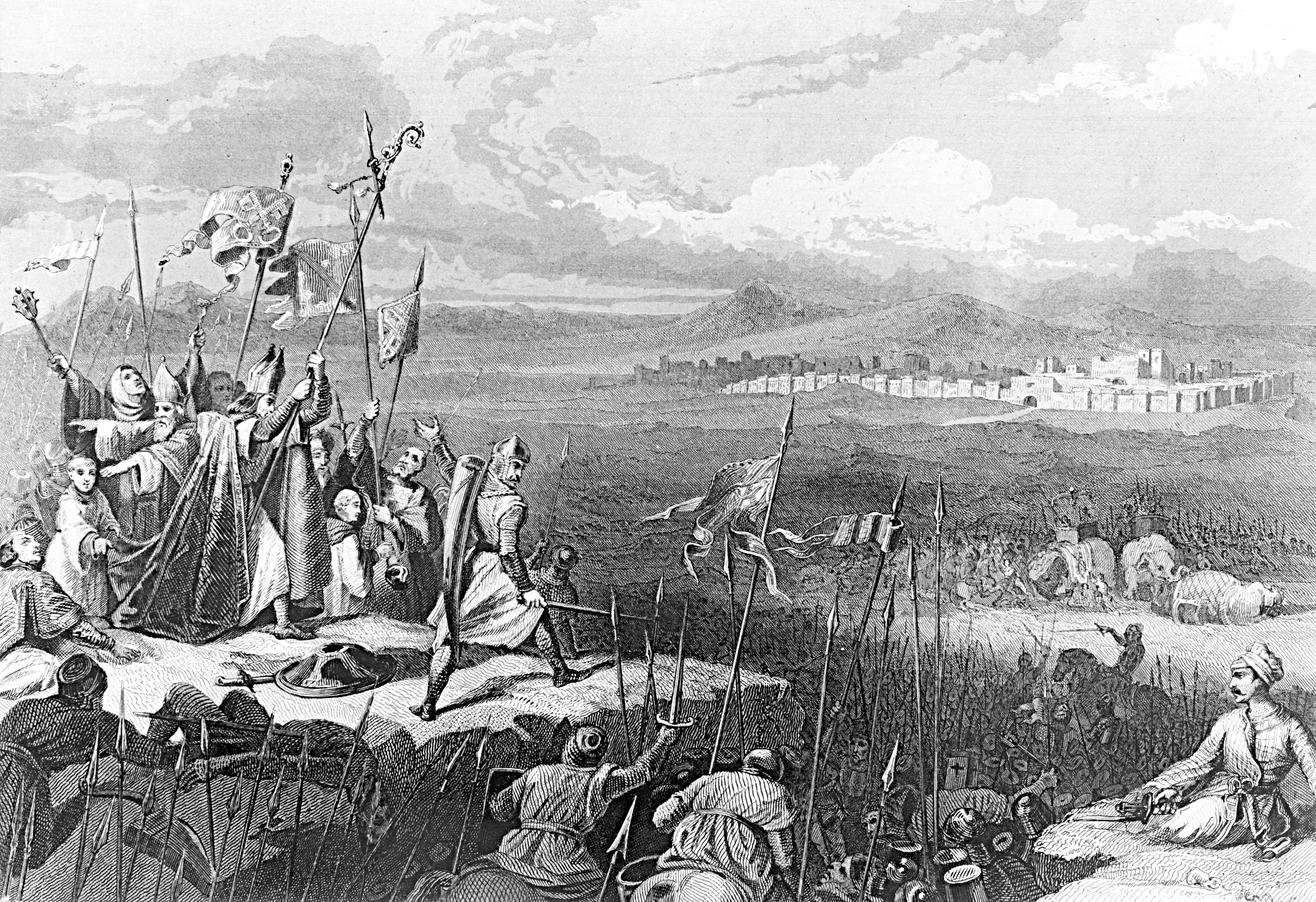

The next morning, June 28, 1098, the Bridge Gate opened and the Crusaders marched out for battle. But now, above all the heraldic banners of medieval Europe, stood another flag, one tacked to a wooden cross and colored with the Lance of Christ. Everyone who could walk followed the fighting men; even the women, common folk, and noble ladies had armed themselves.

Bohemund, who was in overall command, had divided his force into four divisions, with the last held as a reserve. He planned to march his army to a hill some two miles away and force Karbuqa to attack him there. Two divisions made it to the hill. But then Karbuqa, hoping to divide the enemy, struck at the third division under Bishop Adhemar. Once again, the infantry proved its value as Adhemar’s foot soldiers stood their ground in the face of Karbuqa’s frontal assault. When Bohemund saw Adhemar attacked, he wheeled the first two divisions around to support him. At this time, the fourth division came onto the contested field.

Seeing the threat from Bohemund, Karbuqa set grass fires to delay his approach. But the knights and men-at-arms smothered the fires with their own cloaks. When Adhemar saw the first mailed figures charging through the smoke, he bellowed out “Deus le veult!” Bohemund, with the three divisions now at his command, raced to close the gap between himself and the fighting bishop. Over the head of Bohemund’s squadrons, the cross with the Lance of Christ was carried in the van. When the priest carrying it was killed, Raymond the chaplain picked it up.

The Elite (and Feared) Norman Calvary

The entire Christian line surged forward in echelon, trapping Karbuqa between Bohemund’s force and Adhemar. The battle was ferocious. As Crusaders fell, they passed their weapons to the living. Camp followers with their pitchforks joined the line of soldiers with their spears. Knights who had been too weak from hunger only days before mounted their valiant destriers—those that were left—and wielded their heavy swords and battle axes in a grim dance of death with the Seljuq cavalry. Lances skewered lightly armed Turkish archers.

Now Bohemund’s blood-red flag surged forward as he led the reserves of the army in an attempt to break Karbuqa’s lines. These were the elite, the Norman cavalry of Bohemund and his nephew Tancred, the warriors who had carved out a kingdom in Sicily just as those with William the Bastard, Duke of Normandy, had at Hastings in 1066, some 32 years before.

The final push of these Normans cracked the Seljuqs’ will to fight. Hit hard by the armored wall of the Norman cavalry, the Muslim army buckled. Karbuqa tried to make a stand in front of the rich tents of the Seljuq camp, but the mailed torrent swept him and his men away. Giving up all hope, Karbuqa joined the rout, fleeing the deadly lances of the knights of Europe. Duqaq had prudently left before the final battle had begun.

Thus the Battle of Antioch was won. Before the dust was even settled, Tancred was leading skirmishers down the road to the Crusade’s next target, Ridwan’s Aleppo. Before Antioch had been taken, there was no hope of the Crusaders’ advancing. Now there was no chance of their turning back.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments