By John D. Gresham

For much of its history, artillery has been a weapon of mass destruction and attrition, a force designed to cause casualties, destroy fortifications, and wear an enemy down with its noise, explosions, and shrapnel. In fact, since the advent of gunpowder-based fighting forces, heavy guns have been the largest cause of wartime casualties other than disease and starvation.

Often, the fire from these guns was anything but precise or aimed. The modern science of ballistics only came into being with the arrival of minds like those of Galileo and Newton, and still is as much an art as a science. But in the history of artillery, there has been one class of gun designed for the express purpose of putting fire onto a target with a high level of precision: the mortar.

Blessed with a high angle trajectory to the target and clearly visible weapons effects, mortars have been the precision bombardment tools for armies dating back to the earliest days of gunpowder. When a scientific understanding of ballistics was added, mortars became the backbone of siege operations in the period leading up to the American Civil War. That conflict was the last in which classic smoothbore weapons formed the core of the artillery. Still, the Civil War saw mortars as the backbone of long, drawn-out siege operations like those in front of Vicksburg and Petersburg. Mortars also became an important factor in amphibious operations like the assault on New Orleans and defense of Charleston harbor. Nevertheless, very little has been written on these vital guns, because of the highly mobile nature of the War Between the States. However, a closer look at mortars is essential to appreciating why some Civil War battles took so long, while others went quickly or were not even fought at all.

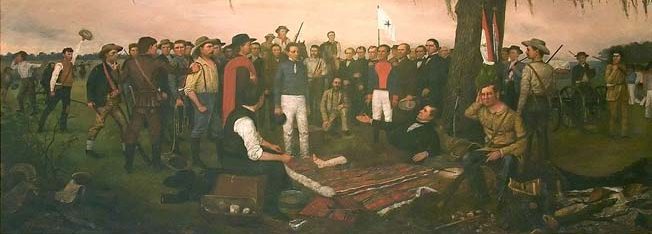

The First Shot of the American Civil War

It is a point of interest that the very first shot of the American Civil War was fired by a Confederate mortar at Fort Johnson on James Island, west of Fort Sumter. There, at 4:30 am on April 12, 1861, Captain George S. James touched off a 10-inch mortar acting as the signal gun that commanded the Confederate batteries ringing the harbor to open the bombardment on Fort Sumter. From that moment on, mortars would be used until the end of the war as the primary precision bombardment weapon. Despite this great contribution to the war effort on both sides, mortars are rarely talked about in terms of final victory, probably because they are seen primarily in terms of the great sieges and static actions of the war. In fact, mortars were present at virtually every major action of the Civil War. Their lack of tactical agility, though, has caused them to be viewed somewhat like boat anchors or anvils: not part of the more mobile actions that grabbed the headlines.

To better understand the contributions of mortars in the Civil War, it helps to know something about their characteristics. They were among the earliest types of heavy guns. Unlike the lightweight tubular units that are so well known on today’s battlefields, mortars in the gunpowder era were heavy and looked like big cooking kettles. The comparison is not without merit, for mortars are shaped in this fashion for much the same reasons as a cooking pot: to help spread the heat and stresses of operation evenly throughout the metal, and to deliver its product evenly and consistently. In gunnery as in gourmet cooking, such qualities are highly desirable.

Another thing about gunpowder-era mortars that defined their use was their weight and bulk. Unlike the long-barreled field artillery pieces that became common during the Napoleonic era, mortars were much heavier and more difficult to move. In particular, the need to mount the mortar on a solidly emplaced bed meant that they were rarely used in the big, maneuver-based Civil War battles such as Gettysburg and Shiloh. On the other hand, Civil War generals saw mortars as a key part of the siege train that the armies used to reduce fortified enemy positions or towns. In fact, so technical had siege operations become by the 18th century that skilled combat engineers were able to project in advance the fall of a particular fortification line within a few hours of actually doing so.

There were several varieties of Civil War mortars, mostly differentiated by their size, mounting, and missions. The smallest of these was known as the Coehorn mortar, after the 16th-century Dutch engineer Baron von Coehorn, who designed it. These weapons were “portable” in the same sense that a sewing machine with a handle is, which is to say that four men could move one a short distance from its carriage wagon. Weighing in at between 50 and 150 pounds, they were usually mounted on a wooden box with the aforementioned handles used to lug them into position. The mortar would then be dug in and fired.

A 17 lb. Shell That Could be Fired 1,200 Yards

The Coehorn, like all mortars of the era, was loaded with powder and an explosive shell, then fired with a standard artillery primer. Coehorns normally came in two sizes, 12- pounder and 24-pounder, though some were defined by the diameter of the shell they fired. The 24-pounder, for example, could fire a 17-pounder explosive shell up to 1,200 yards, with surprising accuracy when handled by a skilled crew.

The explosive shells themselves were remarkable, because not only were they made of traditional cast iron, but also sometimes of wood. The shells were fused so that they could be set to explode precisely where and when desired. A short fuse might be cut so that the shell would explode over the heads of soldiers, the blast and shrapnel raining down with deadly effect. A longer fuse would allow the shell to bury itself inside the earth before exploding, helping to erode or destroy earthen fortifications. In all cases, the mortars and their shells made an evil noise, something that demoralized their victims.

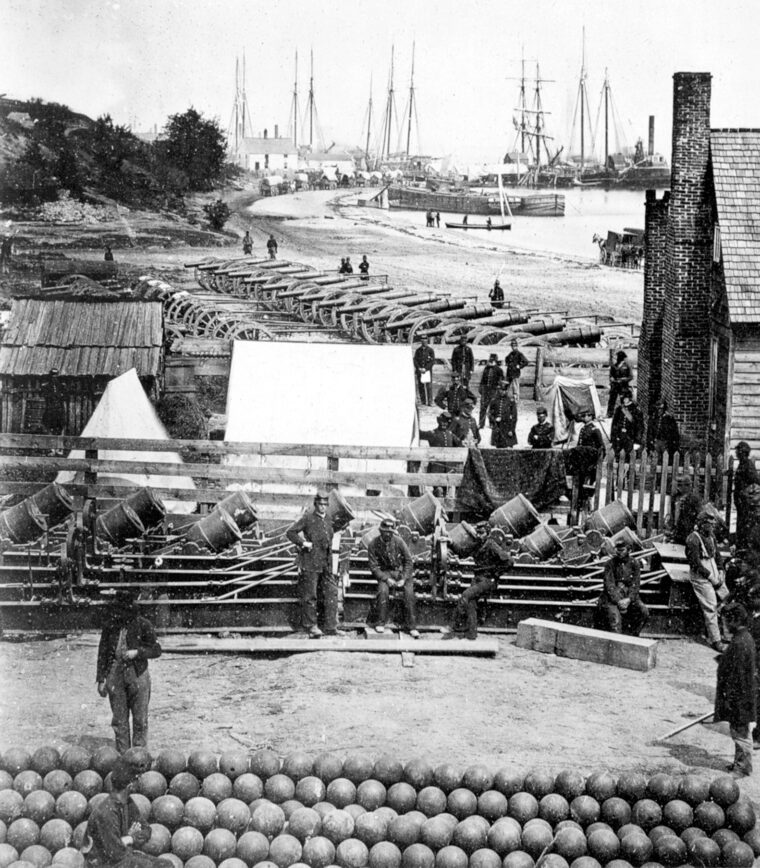

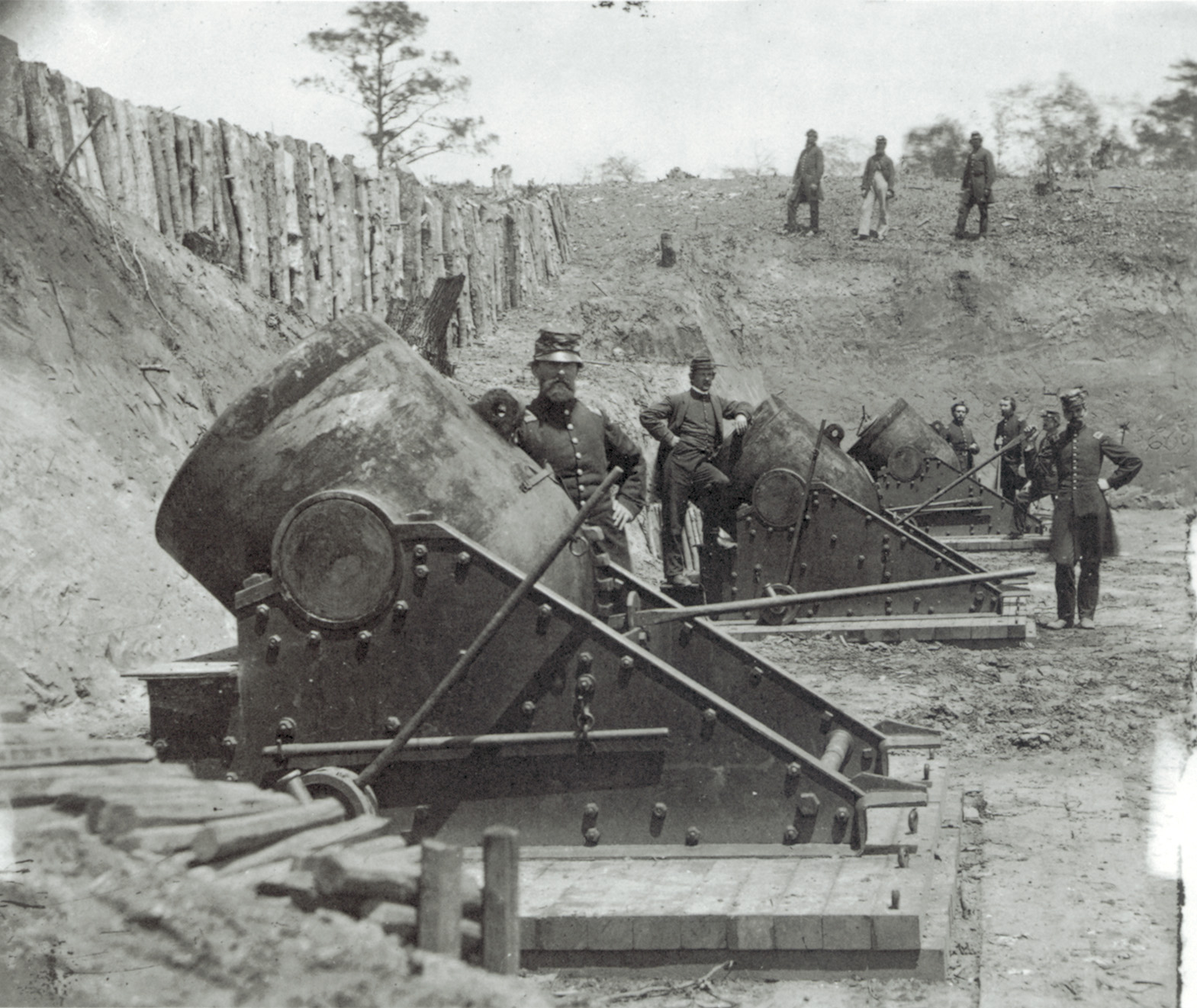

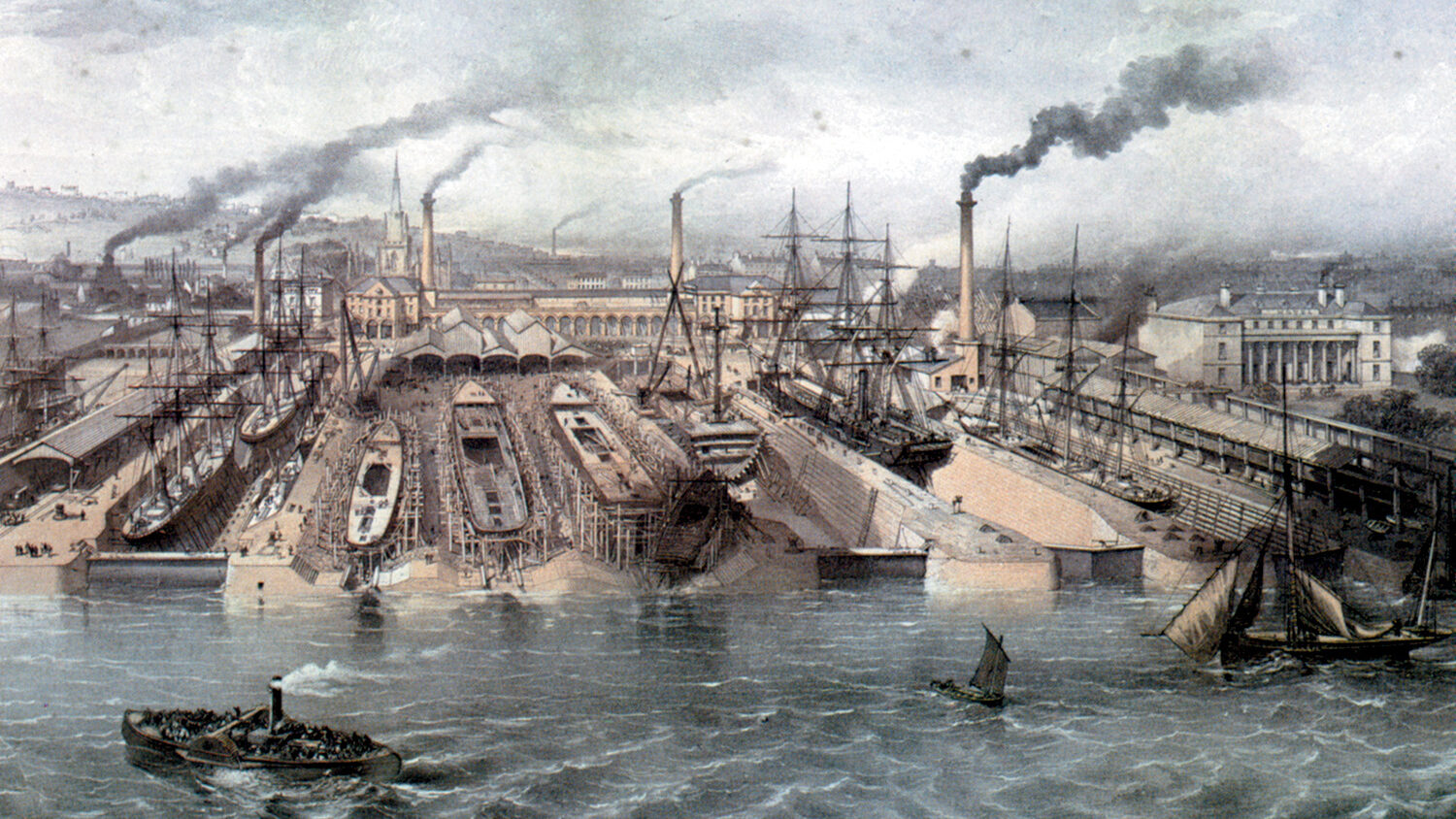

Another class of mortars, used mainly in seacoast defense, was designed to be permanently emplaced in forts or coastal batteries. These were very heavy guns, designed to ruin naval vessels or, as in places like Charleston harbor, a fort in enemy hands. Normally defined by their bore size, these were large, heavy, and designed for decades of service out in the open. The most common sizes were 8-inch, 10-inch and 13-inch weapons, usually fastened either on permanent platform mounts or on specially built barges called “mortar schooners.”

These seacoast types were immense weapons, able to lob 50- to 200-pound shells up to 4,325 yards. Flight times from firing to impact might run up to 40 seconds. Laying these weapons accurately onto a target in the 1860s was as impressive a feat as launching an ICBM in our time. Everything from temperature and humidity to crosswinds and impact time figured into the use of these gunpowder leviathans, and they gave impressive results for the effort.

Similar in size and configuration to the seacoast mortars were those assigned to the army for siege operations. These were usually fitted with horse-drawn carriages and caissons, and took some time to emplace. However, when fully dug in and sighted, they could fire a shell every few minutes for as long as the crew and ammunition held out. Some siege mortars were fired continuously for months at Vicksburg and Petersburg, a testament to their reliability and toughness.

Bizarre and Improvised Homemade Mortars Were Also Used

Along with purpose-built mortars, there also was a bizarre class of improvised weapon made from wood. These were constructed of layers of hardwood, bound by iron straps, with a hole bored into it for the powder charge and shell. These homemade versions had the advantage of being lighter in weight, but they also had an ugly tendency to come apart or explode under stress. Nevertheless, such Coehorn-sized mortars proved valuable, particularly for Confederate forces short on iron, bronze, and other scarce metals.

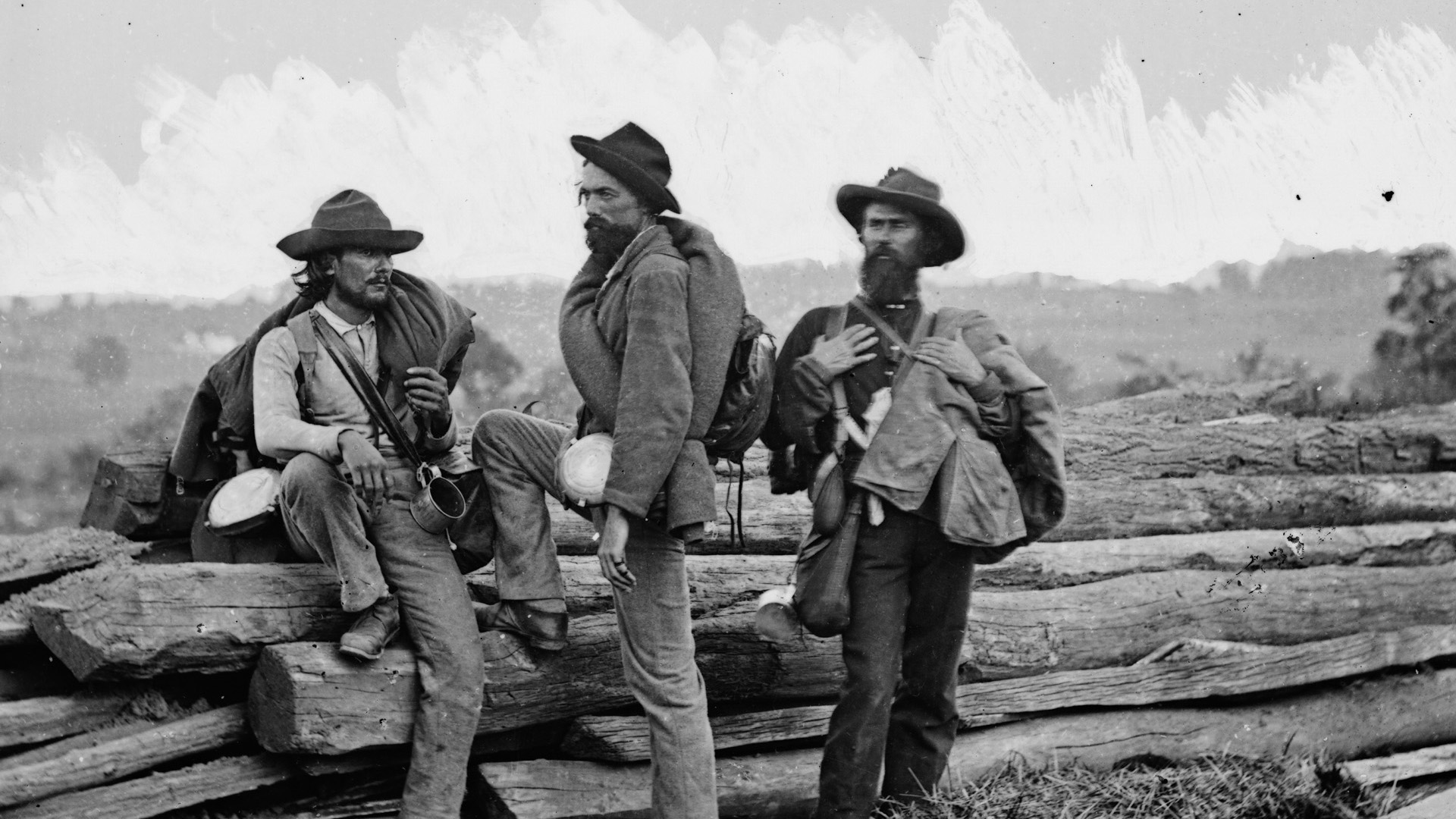

This brings up another important point, which is that both North and South used mortars extensively. Unfortunately for the Southern forces, though, their inventory of these weapons was based mostly on captured Federal ordnance acquired from Northern forts and arsenals taken over at the time of secession in 1861. The Union forces had no such limitations, and often formed their mortar units into the so-called “heavy” divisions used to defend fortifications such as those ringing Washington, DC. Others formed the aforementioned siege trains, which moved with the Federal armies as they began to penetrate the Southern homeland.

One of the first of these expeditions was General George McClellan’s ill-fated Peninsular Campaign toward Richmond in the spring of 1862. On several occasions, most notably in front of Yorktown, McClellan ran into fortifications he believed would require his siege guns to reduce and break. Unfortunately, the time required to bring the mortars and other heavy guns forward allowed the Confederate forces under General “Prince John” MacGruder to withdraw, the first of several such retrograde movements they would make. McClellan was never able to close to within siege range of Richmond to bring his mortars and other big guns to good effect.

Mortars saw somewhat greater success in 1862 in the hands of a new Union general named Ulysses S. Grant. Teamed with a talented naval officer, Commodore Andrew Foote, Grant conducted a series of brilliant amphibious assaults on Confederate forts in Tennessee. At Fort Donelson and Fort Henry, Grant and Foote used river steamboats, ironclads, and a small fleet of flat-bottomed mortar barges to bombard, assault, and capture each bastion in succession. Although unpowered and requiring a tow to get into position, the 13-inch naval mortars on the barges proved invaluable in the confined riverine operations that became the norm in the Western Theater.

Later, Foote would use similar mortar barges to reduce Island No. 10 on the Mississippi River, the first step on the road to Vicksburg. These guns threw 200-pound shells into the Confederate fortifications, greatly reducing the time and casualties required for the Union forces to capture them.

Mortars mounted on more seaworthy schooners would also play a key role in the capture of the first major Southern city: New Orleans. Under command of the legendary Admiral David Farragut, the Union Navy bombarded, reduced, and captured two key bastions, Forts Jackson and St. Philip, some 70 miles downstream of New Orleans. Twenty miles upstream from the Head of the Passes, the two forts were the keys to capturing the city, and Farragut used his own touches to do the job. Under the command of his stepbrother, Commodore David Dixon Porter, the mortar schooners (called “bummers” by their crews) were brought into position and began to bombard the two forts on April 18, 1862.

16,500 Shells Fired Over Six Days

Over the next six days, the mortar schooners lobbed some 16,500 shells into the two forts, though not without cost. One mortar schooner, the Maria J. Carlton, was sunk by return fire, and the two forts still stood up well to the withering fire. Farragut actually became impatient with Porter’s insistence that mortars alone could reduce the forts, and beginning at 2 am on the 24th, ran his big ships past the two stalwart defenses, supported as they went by the fleet of mortar schooners. Now with Union forces surrounding them, the two forts surrendered on April 28. New Orleans followed on May 1, the threat of a massive mortar bombardment of the South’s largest metropolis being enough to scare the town fathers into declaring it an “open city.”

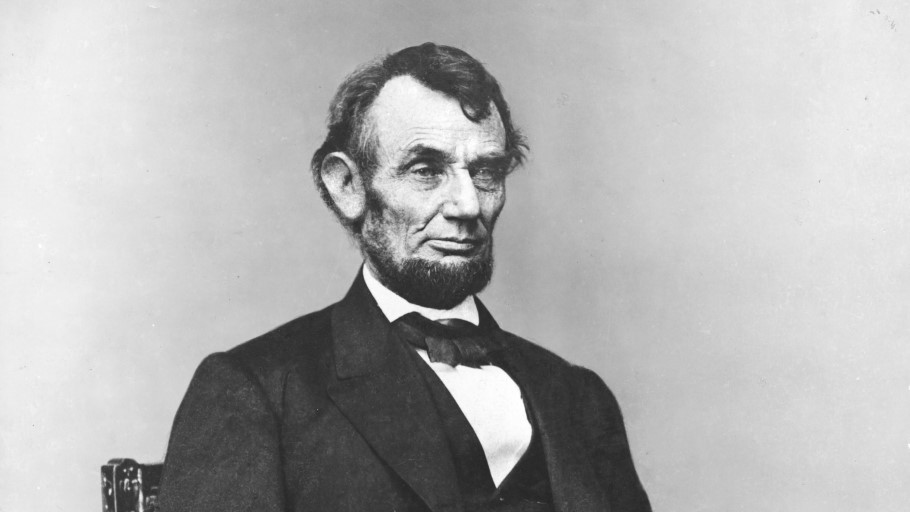

Similar operations eventually would allow the Union forces to reach the final roadblock to control of the entire Mississippi: the town of Vicksburg. For over a year Union forces under Farragut, Grant, and others would try to invest Vicksburg, though it would be spring 1863 before the city was surrounded. This led to the first great siege of the war, running for seven weeks in May, June, and July of 1863.

Supported by naval forces under David Porter, Grant’s command surrounded the town and began a continuous bombardment by everything in the Union arsenal. This time, with the Confederate defenders surrounded, Grant was able to bring all of the Union siege tools to bear. Permanent siege lines and batteries were established, with mortars and guns of every variety firing from the land side of the town. From the river, Porter’s mortar schooners and barges did their share of damage as well. By the time Grant’s soldiers marched into Vicksburg on July 4, the city looked like the surface of the moon, a terrible suggestion of what firepower might do on a modern battlefield in the years to come.

Another campaign in which mortars were critical was the attempted bombardment and amphibious assault on Charleston in 1863.

Commanded by Admiral Samuel DuPont, this expedition intended to use ironclads to reduce Fort Sumter and other batteries in the harbor, then land troops and siege guns to bombard the city into submission. Unfortunately for the Union forces, the Confederate artillery, under command of General P.T.G. Beauregard, repulsed the Union assaults through effective use of their own guns and mortars. While Union mortars and heavy siege guns (including the famous “Swamp Angel”) laid waste to portions of Charleston, the Northern forces never got enough firepower into place to complete the effort. It would take an attack from the land side of Charleston by General Sherman in 1865 before the city would finally fall.

No-Man’s Land

Without question, the largest and most impressive use of mortars in the Civil War transpired when General Grant laid siege to Petersburg, just south of Richmond. Beginning in the late summer of 1864, the armies of both sides dug in around Petersburg and began a continuous bombardment that would last until April of the following year. Confederate forces, lacking materiel and resources, often had to depend upon improvised wooden mortars to fire back at increasing numbers of Union guns. The landscape around Petersburg began to resemble the “No-Mans Land” of World War I, with both sides reverting to trench warfare when direct Union frontal assaults failed to break the Confederate lines.

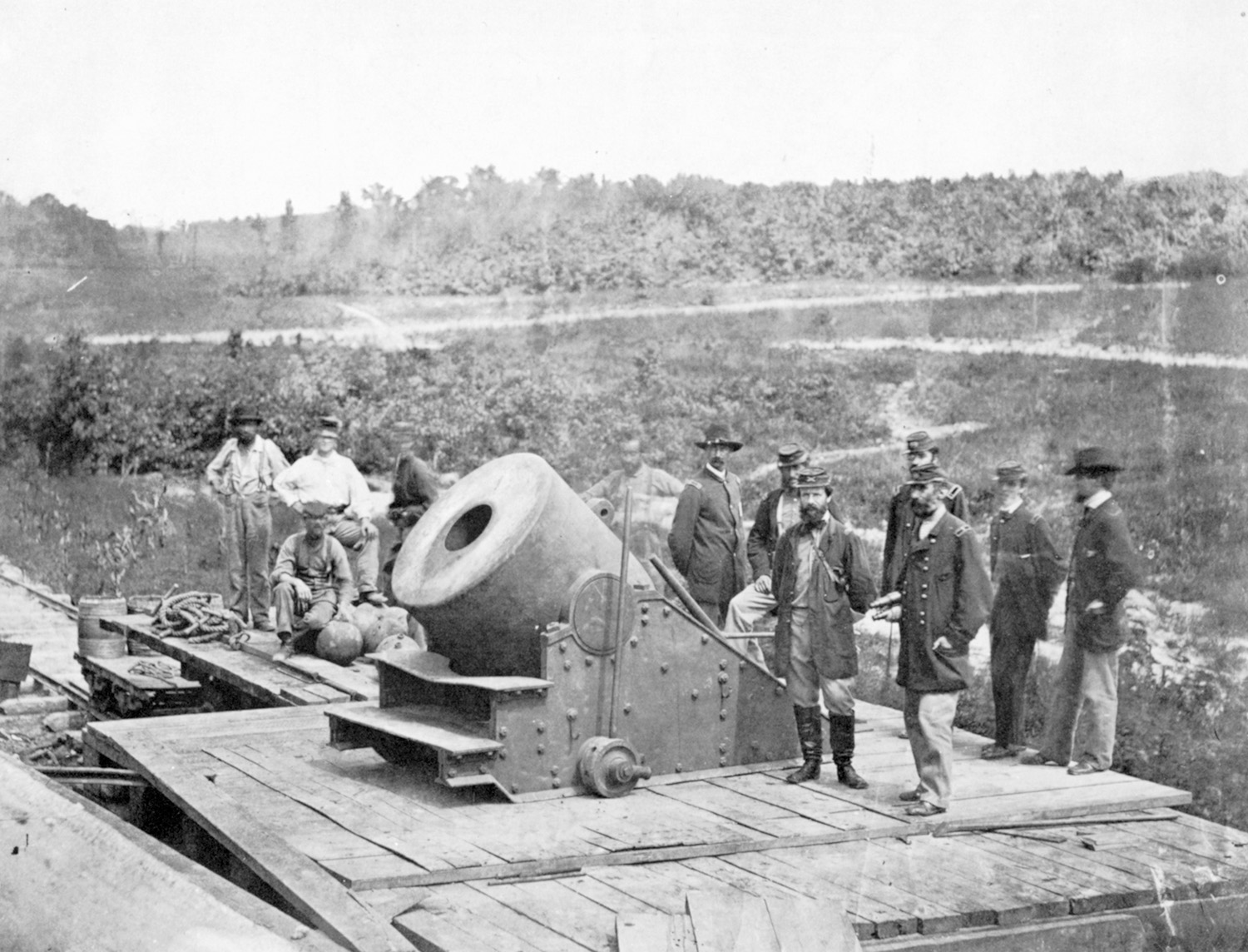

During the siege, the Federals put to use the heaviest siege weapon of the war, a 13-inch seacoast mortar known as “the Dictator,” mounted on a rail carriage. This first use of a rail mounting proved to be one of the earliest such instances of mobile artillery. One of the more interesting features of its use was a curved section of track, which allowed the Dictator to be aimed at targets across a wide traverse arc. Hundreds of Union mortars, guns, and cannon bombarded the Confederates until April 1, when General Robert E. Lee ordered a final desperate counterattack against the Union lines. This final attempt to end the Union siege of Petersburg was broken up by an incredible bombardment, one of the last that the mortars would contribute to in the war.

When the attack failed, Lee withdrew his army from the Petersburg line, and the Confederacy had less than three weeks to live. When Lee’s forces were surrounded near Appomattox Court House two weeks later and faced the fury of Grant’s siege train once again, the Confederate general surrendered rather than suffer further needless casualties.

Thus mortars played a great role in the Union victory in the Civil War, one that is rarely noticed or appreciated. It was a fear of what siege guns like the mortar would do that led to the surrender of so many Confederate forts, cities, and soldiers. The combination of great accuracy, firepower, and noise made mortars hated by their victims and treasured by their owners. Cheap, easy to produce, and effective in their operations, mortars did their job well in 1861-1865.

Unfortunately, the lesson about the potential of massed artillery fire was lost on the generals of the next two generations, something that would cost millions of men their lives in World War I. It would be an expensive lesson indeed for those 20th-century leaders to learn anew.

Join The Conversation

Comments