by Eric Niderost

It was May 1, 1592, mere weeks before the start of the Imjin War. Admiral Yi Sun Shin summoned a conference of high-ranking military officers and civil magistrates to his headquarters at Yosu, a port on the southern coast of Korea. The calendar may have suggested spring, but the day was cloudy and threatened rain. The weather matched the mood, which was heavy with foreboding, and officials exchanged anxious glances as they filed into the Chinhaeru Pavilion.

About two weeks earlier, Japanese troops had landed at Pusan, the first wave of a massive invasion that would eventually number 150,000 men. Consternation reigned and morale plummeted as the grim news filtered into Cholla province—tales of Korean defeats, of towns taken and inhabitants put to the sword. Within three weeks of landing in Korea, Japanese forces had captured Seoul, large parts of which were looted and put to the torch.

As the conference began, Admiral Yi glanced about the room. A shrewd judge of character, he could read the emotions in the faces of the men assembled around him. Some were fearful, some brave, some uncertain. Certainly all looked to him for guidance. Korea’s destiny was in the hands of these men; the country’s independence and their cultural survival as a people hung in the balance.

Tempers flared as the debate grew over what course of action to take. A magistrate named Shin Ho expressed the feelings of many when he said, “It is the prime mission of our navy to defend this [Cholla] province.” Shin Ho’s proposal seemed shortsighted to Song Hi-Rip, who counseled offensive action against the Japanese enemy. “I propose to fight,” declared Song, “however superior the enemy might be. If we win, the enemy will be greatly discouraged. If we lose, our duty as loyal subjects will be accomplished.”

Yi, An Accomplished and Respected Commander

The final decision rested with Admiral Yi, who was a rock of calm in a sea of acrimonious debate. There are no descriptive details, but it’s not hard to imagine the scene: the admiral in full kugunbok uniform, a dark-bodied tunic with red sleeves bordered in yellow. A broad-brimmed jeonrip perched on his head, colorful military headgear trimmed with red-feathered plumes, and his face sported a mustache and goatee. Yi was 47 years old, at the height of his powers, and a man whose military talents and reputation for honesty made him both hated and admired by his peers.

Yi Sun Shin was for immediate action. “The national security has been greatly endangered by the invasion of an overwhelming enemy. For this reason, we can no longer commit ourselves only to the defense of our own sector. Now the only way left for us is to go out and to fight until death.”

Brave words, but an offensive against a superior enemy must have seemed foolhardy in the extreme. Much of the country was already overrun, making a defense at such a late date seem an exercise in futility. And Admiral Yi commanded a naval force—how could he hope to influence military events on land? A lesser man might have given up, but Yi Sun Shin was made of sterner stuff. He also wanted to unify his command and strengthen their resolve, declaring, “Today we have only one duty, to fight and die. If anyone says no, I shall cut off his head!”

The admiral soon proved he was a man of his word. When a seaman named Hwang Ok-chon deserted his post, he was brought back and beheaded. The severed head was displayed on a tall pole as a lesson against cowardice and dereliction of duty. Yi Sun Shin was not cruel or sadistic, but simply a man of his times trying to enforce discipline on a shaken command. If he ignored desertion, a trickle of fugitives might become a flood.

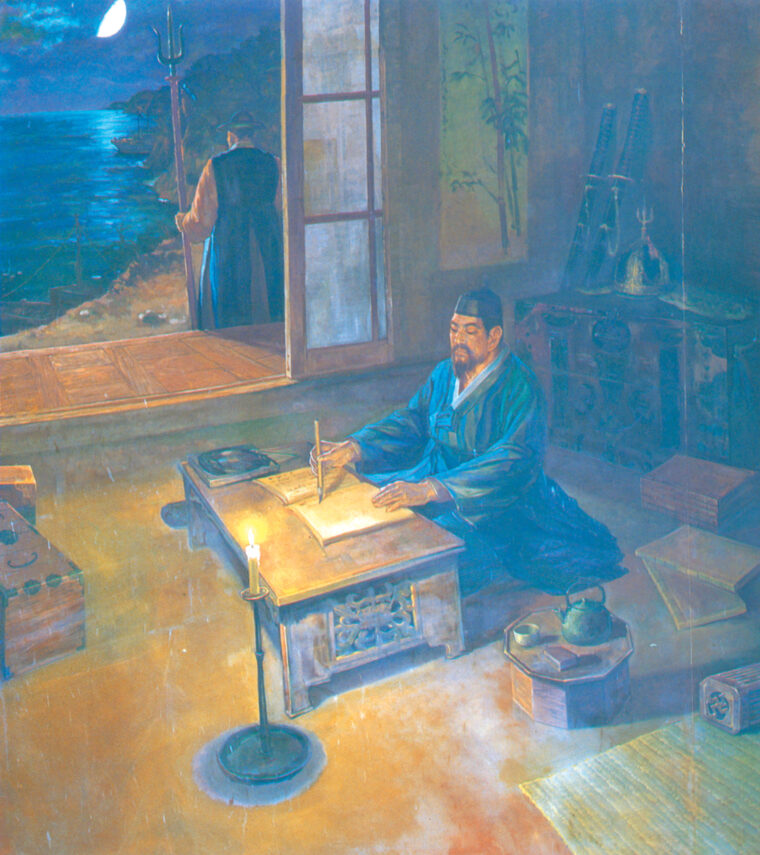

After last-minute preparations were complete, Admiral Yi wrote a report to his superiors declaring his intention to launch an offensive. He was not given to rhetorical flourishes or long-winded self-justifications. There was just the simple statement: “We intend to sail for Kyongangdo [“do” meaning “province”] at the first cock-crow on this day, May 4.” He had only 24 panokson (warships) under his command, together with a swarm of auxiliary vessels. The tiny fleet set sail on schedule, a handful of ships on a quixotic mission to save a nation.

In the 16th century Korea was called Choson, “the land of the morning calm.” Ruled by the Yi dynasty of kings since 1392, Choson’s real power was held by a class of bureaucrat-scholars called yangban. Yangban means “two orders,” because they were civil servants who occupied both civilian and military posts. Essentially a Chinese client state, Choson was influenced by China both politically and culturally. The yangban took up Neo-Confucianism, a system of social behavior and ethics based on the teachings of the great Chinese sage Confucius (Kong Fuzi).

Ambition and Power Lust Led to Corruption in Seoul

Geography is destiny, and the Korean peninsula is a 600-mile-long “appendix” that descends from the Asian continent between China and Japan. Choson/Korea’s location has been both a blessing and a curse. Chinese trade and cultural influence were benign, even beneficial, but Choson’s location has always attracted would-be conquerors.

Around 1575 political infighting became endemic with the rise of factionalism among the Korean yangban elite. Candidates for government posts had to pass examinations, but so many were qualifying that competition was keen. As yangban jockeyed for position, narrow self-interest replaced patriotism and dedication to the state. Yangban did what was good for themselves, their families, or factions, and national interests took second place. Overweening ambition and thirst for power soon produced corruption. Seoul became a hotbed of intrigue.

All this was to have a deadly effect on Choson’s military preparedness. Immersed in their own petty squabbles, yangban military thinking—if they considered such matters at all—was thoroughly traditional. Choson/Korea’s northern borders were always the area of greatest concern, since it was the traditional route of invasion. Mongols had made incursions in the 13th century and Choson was continually troubled by such fierce, hard-riding tribes as the Jurchen (later Manchu).

Japanese pirate raids had been a severe trial in the 15th century, but on the whole the seas that cradled Choson were considered more protection than threat. A series of “brush fire” wars with the Jurchen tribes in the 1580s tended to confirm the notion that the northern border held the most danger for the Korean nation. In the 16th century the line between a navy and army career was less sharply defined than it is today. Yi Sun Shin first honed his military skills fighting the Jurchen tribes.

While yangban civil servants squabbled, or warily eyed the nomadic tribes in the north, a new power was rising to the east 120 miles from Choson’s shores. During much of the 16th century Japan had been nearly torn apart by internecine wars, a period still known as Sengoku-jidai (The Age of the Country at War). After a series of bloody clashes Toyotomi Hideyoshi emerged as victor. Even today Japanese revere Hideyoshi as the man who unified their country.

Humble Hideyoshi

Toyotomi Hideyoshi was a man of humble origin, a peasant boy who started his career as a simple ashigaru or foot soldier. Hideyoshi was a good soldier, efficient administrator, and masterful politician, attributes that enabled him to rise and eventually overcome his more aristocratic rivals. Using the carrot-and-stick approach, he maintained control by generously rewarding retainers and punishing—or at least politically neutralizing—rivals. Although nominally subordinate to the Japanese emperor, Hideyoshi was the supreme power in the land, confirmed by his title of kampaku, or Imperial Regent.

As early as 1586 Hideyoshi dreamed of foreign conquest. China, the great civilization that excited the envy and admiration of all Asia, was an obvious target. Hideyoshi’s successes had created a momentum of conquest, a heady atmosphere of victory where anything seemed possible. The kampaku boasted to the emperor that “I intend to bring the whole of China under my sway,” adding, “I shall do it as easily as a man rolls up a piece of matting.”

It took time for China and Choson to awaken to the growing menace of Japan.

To them the Japanese were little better than barbarians, crude uncivilized pirates whose plundering raids had plagued Asian shores for centuries. As far as the Chinese and Koreans were concerned, Japan was a pariah nation that should be held at arm’s length.

Ironically, China and Choson’s disdain gave Hideyoshi another rationale for conquest. Japan desperately needed foreign trade, yet China and Choson’s contempt, coupled with Japanese pirate raids, had caused such commerce to decline. To get the goods it wanted, Japan was forced to rely on middlemen, particularly Portuguese merchants, but they charged high commissions for their services. A conquest of China would be a conquest of markets at their source.

Hideyoshi Was Determined to Conquer China

Hideyoshi committed himself to the conquest of China, but before he could proceed he needed Choson’s cooperation, or at least, its acquiescence. The Korean peninsula was a literal stepping-stone to China, an avenue that led figuratively to the gates of Beijing. After some diplomatic exchanges, Hideyoshi sent a letter to Choson’s King Sonjo that requested free passage for Japanese troops en route to China. If the Koreans allowed the Japanese free passage, the kampaku’s envoys assured, Choson’s territorial integrity and independence would be respected. If not, Choson would be invaded and forced to yield by conquest.

King Sonjo rejected Hideyoshi’s overtures, rightly feeling such cooperation would be a betrayal of Choson’s long friendship with China. It was a hopeless situation, but the Korean government stalled for time by engaging the Japanese in protracted negotiations for several years. In 1590 King Sonjo sent an embassy to Japan to find out if Hideyoshi really intended to invade the Asian continent. His diplomats reflected the internal divisions of the yangban, with one envoy feeling the Japanese would invade, another feeling strongly that they would not.

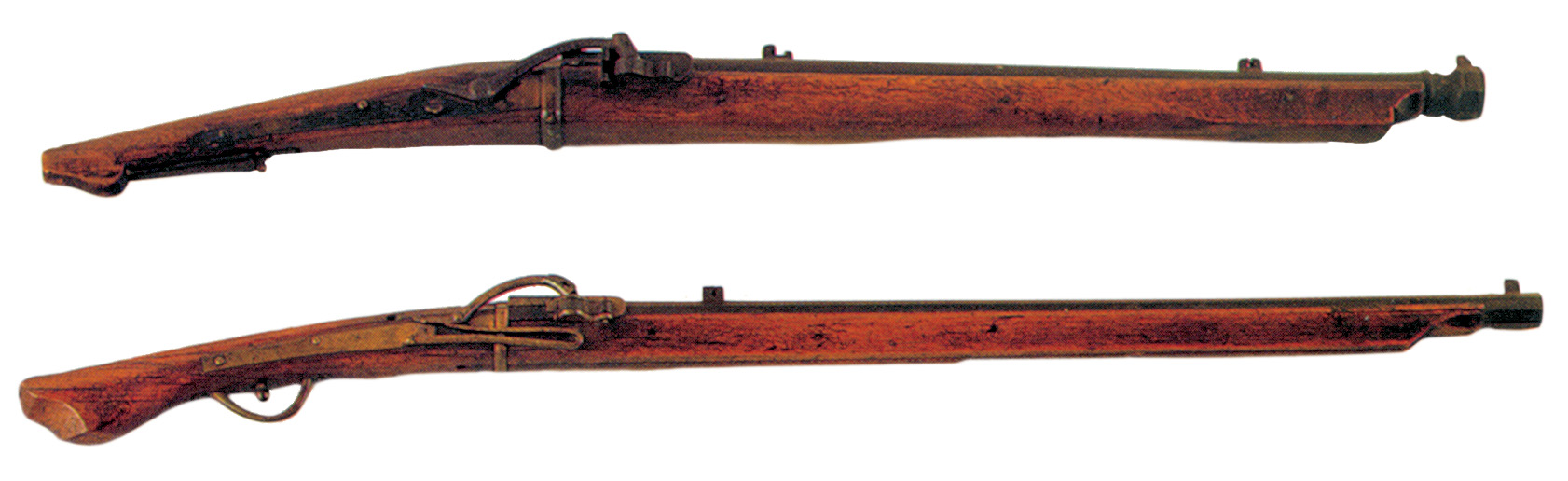

Choson was woefully unprepared for a major war, its troops ill trained and armed with spears and bows. This was at a time when Japanese armies were armed with matchlock muskets called arquebuses. These matchlocks were of a superior European design, introduced by the Portuguese in 1543. Later, during a battle at Pusan, it was said the Koreans laid down a “curtain of arrows,” but were wiped out by Japanese gunfire.

Luckily the king’s chief minister, Yi Song Nyong, was a man of intelligence. Despite considerable opposition he saw to it that a number of towns in vulnerable Kyongsang province were fortified. Incredibly, some had objected to Yi Song Nyong’s program on the grounds the common people would be “alarmed” by such defensive measures. Yi Song Nyong was also instrumental in having his old friend Yi Sun Shin appointed as commander of the chollajwasyong, or the Cholla Left Fleet. His formal title was Chollajwasusa, or Admiral (susa) of the Cholla Left Fleet. Although little noted at the time, this appointment was to prove the salvation of Choson/Korea.

How Admiral Yi Developed a Reputation as a Man Touched by Genius

Admiral Yi took up his duties on February 28, establishing a headquarters at Yosu, along Choson’s island-sprinkled southern coast. A soldier much of his life, Yi was a serious student who read the seven Chinese military classics, including Sun Tzu’s Art of War. He applied the principles he learned, but had the courage to refute such authorities if he felt they were in the wrong. Above all he was gifted beyond any of his peers, a man who was touched with true genius.

While others wasted time debating about the possibility, Yi Sun Shin was positive the Japanese were going to invade. He strengthened the garrisons under his jurisdiction, and trained his ship crews until they worked together like a well-oiled machine. The admiral was well aware of Japanese naval tactics, and knew they relied on grappling and boarding to achieve victory.

A Japanese sea soldier’s “secret weapon” was the kusari kagi, or grappling chain, which was swung over the head and flung forward when it gained enough momentum. The “business end” of the kusari kagi was a four-pronged hook that bit into an enemy ship’s deck and held fast. Thus locked in a fatal embrace, the enemy vessel was helpless while Japanese soldiers tugged on ropes attached to the kusari kagi that brought the two ships closer together. Once a Japanese ship was side by side with its victim, Japanese soldiers could rake it with musket fire and then board.

Yi Sun Shin gave the matter serious thought and came up with a brilliant solution that was so typical of the man: He would resurrect the kobukson (turtleship). Contrary to popular belief, Yi did not invent the kobukson, but modified it and added his own unique touches to its design. There had been turtleships in the 15th century but they had fallen out of favor since that time. No kobukson had been built for over a century, but Yi Sun Shin was about to stage a spectacular revival.

Testing the ‘Turtleship’

The turtleship was a vessel whose vulnerable upper decks were protected by a curved roof. Working closely with a shipbuilder named Na Tae-Yong, Admiral Yi drew up plans that met his own exact requirements.

In a fit of political myopia, officials in Seoul wanted to disband the fleet, the better to concentrate on land forces. Admiral Yi’s forceful arguments against such a move finally prevailed, but it was a very close call. Work on the turtleships continued, with Yi supervising every phase of the construction. He left a war diary that charts in minute detail the progress that was made. Nothing escaped his attention; on February 8, 1592 he records,“Received at headquarters 29 p’il [one p’il is about 40 yards] of canvas to be used in the turtleship [sails].” March 27, 1592 was a typical day for Yi Sun Shin. He writes in his war diary, “I watched the test firing of cannons from the deck of a turtleship.” These preparations proved timely, because on April 13 the Japanese invaders appeared off Pusan. Their arrival marked the beginning of the Imjinwaeran, or Imjin War. “Imjin” is the name of the year 1592, based on two Chinese characters from a 60-year Chinese calendar cycle.

There is some controversy about how many turtleships were built and saw combat. In 1979 a group of historians studied the matter and felt three kobukson were constructed. Others say as many as 20 were built. No one knows, but the admiral probably had at least three to five turtleships.

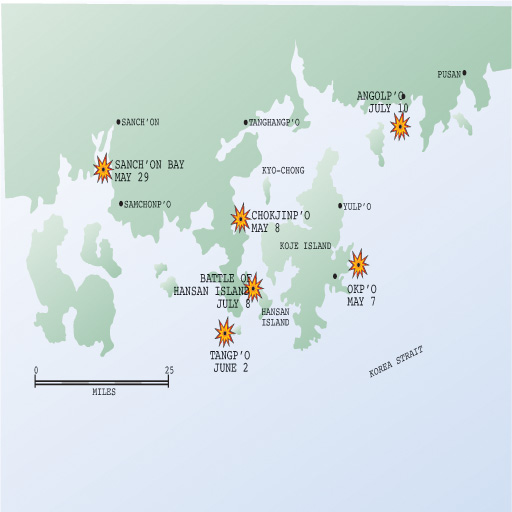

The coming naval campaigns against the Japanese would be fought along a 93-mile stretch of the southern Korean coast now known as the Hallyeosudo Waterway. A region of great natural beauty, Hallyeosudo is a labyrinth of channels, bays, and inlets punctuated by four hundred tree-crowned islands and islets.

Yi Sun Shin’s efforts to mount an adequate naval offensive were hampered by the cowardice and incompetence of his colleagues. Like Cholla, neighboring Kyongsang province was divided into a Right and Left naval command. The Kyongsang Left Admiral Pak Hong literally deserted his command, taking to his heels when he saw the might of the Japanese armada. Kyongsang Right Admiral Won Kyun wasn’t much better. A man noted for drunkenness, he seems to have panicked and ordered his fleet to be scuttled to prevent it from falling into enemy hands.

Bloodless Victory for Japan

Over a hundred badly needed warships went to the bottom, in essence handing the Japanese a bloodless victory. The thought that such ships might have been useful for fighting the enemy doesn’t seem to have entered his drink-befuddled mind. The invasion might have been stopped in its tracks if Yi Sun Shin, not Won Kyun, had been in command. Only three ships of the Kyongsang Right Fleet escaped this self-inflicted debacle.

Although Yi Sun Shin heard of the Japanese invasion on April 15, he took no immediate action. There were sound reasons for delay. He was unfamiliar with the waters around Kyongsang province, but most of all he lacked adequate intelligence on enemy positions and strength.

The Cholla Left Fleet departed from Yosu at 2 am on May 4, 1592. Yi Sun Shin divided his forces into six (some say four) squadrons, each commanded by a man personally chosen by the admiral. Not all of these men were career naval officers; many were town magistrates or other civil servants. Courage and devotion to duty were the main qualifications for the assignments.

Other naval units joined Yi Sun Shin’s force, including a handful of ships under Kyongsang Right Admiral Won Kyun. Accounts differ, but he now had somewhere between 85 and 91 vessels under his command.

The first battle of the sea campaign took place at Okp’o on May 7. Okp’o is a seacoast town on Koje Island (or Koje-do; do can also mean “island”). About 50 Japanese ships rode at anchor along its waterfront, but only skeleton crews were aboard. The bulk of the Japanese soldiers and sailors were conducting a plundering raid, looting and burning with wild abandon. Houses were sacked, and anyone who resisted being robbed was ruthlessly cut down. Smoke from the burning buildings hung over the town like an omen of death, the cries of the inhabitants and the crackling flames mingling to produce a funeral dirge.

“They Were Like Beasts or Devils and Enough to Frighten Anyone”

It was about noon when scout ships gave Admiral Yi definite information the enemy was at Okp’o. He gave the order to sail to Okp’o at once, though he did admonish his officers to “Move as calmly and prudently as a mountain.” Once the Korean fleet arrived they attacked at once. It was Yi’s first glimpse of the Japanese samurai, who looked fierce when they wore their hideous face-mask protectors and elaborate helmets. “They were,” the admiral noted later, “like beasts or devils and enough to frighten anyone.”

But it would take more than frightening face masks to deter Yi Sun Shin. The Koreans advanced, filling the air with clouds of arrows and a storm of cannon shot. Caught completely by surprise, the Japanese marauders, knowing they might be cut off from the mainland, dropped their ill-gained loot and began running to the safety of the ships. In a frantic effort to get under way, Japanese sailors jettisoned cargoes overboard to lighten the ship. Some lucky Japanese vessels just managed to escape, but others fell victim to Korean artillery and arrow fire. When fighting ceased, 26 Japanese ships had been destroyed out of an original total of about 50. Admiral Yi had not lost a ship or a man. It was a major reverse for the Japanese, since they had grown accustomed in these early weeks to walkover victories.

Immediately after the action at Okp’o, Yi Sun Shin ordered a withdrawal to Yongdungpo to spend the night. About five o’clock on the afternoon of May 7 a message came to Admiral Yi as his men were preparing for dinner. The missive said five large Japanese warships had been sighted nearby. Timing can be everything in war; the Admiral wasn’t going to placidly eat rice and leave the enemy unmolested. Yi ordered a pursuit, and soon the Japanese ships were caught and sunk near Happ’o.

The very next morning Yi Sun Shin received some fresh intelligence: 13 Japanese ships were off Chinhae. Responding with alacrity, he sent the fleet after this new target. The enemy was run to ground at Chokjinp’o, where once again shore parties were busy plundering the town. The Koreans hit hard and fast, sinking the Japanese ships so rapidly the crews were literally stranded on shore. Their retreat cut off, Japanese soldiers fled to the mountains. Eleven Japanese ships were sunk out of the original 13 ships that raided the city.

Thus in the space of two days, May 7 and 8, 1592, Admiral Yi had inflicted three small but psychologically significant defeats on a victorious invader. The initial phase of the campaign was over; supplies were short, his men were exhausted, and Korean ships had sustained battle damage. For these reasons Yi Sun Shin ordered a return to his Yosu naval base. Once the fleet was rested, repaired, and refitted, he intended to renew the offensive.

The Korean victories at Okp’o, Happ’o, and Chokjinp’o were the only bright spots in the Imjin War’s descending spiral of defeat and despair. After the occupation of Seoul, Japanese armies fanned out to consolidate and expand territorial gains. General Konoshi Yukinaga’s troops assaulted P’yongyang, Korea’s ancient capital, and took the city on June 15. Another army under General Kato Kiyomasa pushed eastward to conquer the provinces of Hamgyong and Pyong’an, even crossing the Tumen River into Manchuria.

Whole Korean Villages Sold Into Slavery

After conquest came exploitation. General Mori Terimoto complained in a letter to home that “the Koreans regard us in the same light as pirates.” Indeed, this was piracy, only piracy on a national scale and officially sanctioned by the Hideyoshi government. Rice and other foodstuffs were confiscated, and cultural treasures ruthlessly looted. The Korean people themselves were targeted, with whole villages kidnapped and sold into slavery in Japan. Hideyoshi was pleased; with Choson apparently occupied, his real goal, the conquest of China, could begin.

Admiral Yi was naturally upset by these calamitous events, but his basic resolve remained unshaken. Early in the war he wrote, “We have mapped out a strategy to cut off the path of retreat for the enemy by destroying enemy ships. If successful, this strategy may drive the enemy to turn back south out of fear his rear might be endangered.” In this way naval victories would have a significant, even decisive, impact on the land war.

In late May Yi Sun Shin received disturbing reports of enemy activities. The main Japanese fleet had arrived in Choson waters, their principal purpose to clear the sea-lanes of Korean resistance. The Japanese had bypassed Admiral Yi’s Cholla province in their initial drives north. Now, however, there were reports of tentative Japanese probes into Chollado, known to be rich in grain.

Yi Sun Shin had only 23 warships under his immediate command; the fishing boats of the previous campaign had been dismissed as worse than useless. But the turtleships were now operational, which gave the Left Cholla Fleet the edge it needed to combat the Japanese. Once he made sure that Cholla’s land defenses were in order, Yi departed Yosu at the end of May. He sent a dispatch to Right Cholla Admiral Yi Ok-Ki, then made a rendezvous with Kyongsang Right Admiral Won Kyun and his three vessels at Noryang.

The small Korean fleet now made its way to Sach’on Bay, its ultimate destination the seacoast town that gave the waterway its name. A series of undulating hills rose above the town, eventually culminating in a rocky ridge that was crowned by a Japanese tent. Yi Sun Shin surmised the tent was some kind of headquarters, because soldiers could be seen scurrying in and out, as if receiving orders.

Defiant Samurai Drew Their Swords

The Japanese seemed to be here to stay; around four hundred soldiers were busy building a serpentine emplacement, the position festooned with red and white flags that flapped in the wind. Twelve large Japanese ships were at the wharf, tempting targets for Korean cannon and fire arrows. The samurai were defiant, quickly drawing their swords and brandishing them at the approaching Koreans as if to issue a challenge.

Admiral Yi was ready to pick up the gauntlet, but was faced with some serious problems. The Japanese held the high ground, and were beyond the range of Korean guns. Night was falling, and the tide was ebbing, making it next to impossible to enter the harbor. Yi decided on a ruse, a clever stratagem designed to lure the enemy out into the open and beyond Sach’on harbor’s protective embrace. He ordered his ships to feign a retreat, a maneuver that was done so convincingly the Japanese eagerly took the bait.

The action at Sach’on was the first time the turtleship was used in the Imjin War, and it was an auspicious debut. When the Japanese ships came out to chase a “fleeing” enemy, they soon found the tables had turned. The hunters now became the hunted, with the Korean attack spearheaded by at least one kobukson. The turtleship’s guns blazed with a deafening roar, fingers of flame and jets of smoke marking each lethal discharge.

The admiral’s anger was roused when he saw that there were Korean collaborators in the Japanese ranks. He ordered his flagship—a panokson battleship, not a kobukson turtleship—to increase to full battle speed. His rowers worked their oars with a will, until they were in the midst of the Japanese vessels. Inspired by the turtleship’s success and their commander’s example, the rest of the Korean fleet followed.

Korean cannonballs smashed into the Japanese ships, splintering cedar hulls to “kindling,” and Korean arrows pelted Japanese crews. Japanese ships were burned or sunk by ramming, much to the consternation of the samurai still on shore. Thirteen Japanese ships were destroyed at Sach’on, yet Admiral Yi did not lose a single vessel.

Yi Narrowly Avoids Death

Korean casualties were light, but one of the wounded was Yi himself. He had been struck in the left shoulder by a musket bullet and, though blood was pouring from the wound in a crimson flood, he refused to have it tended until victory was assured. Later, he amazed his staff with his normality and even cheerfulness in spite of his great pain. Yi himself says the bullet passed clean though; another story says it penetrated about two inches into his body and had to be dug out. A little lower, and he could have been killed. A little lead bullet might have profoundly altered the course of Korean and Chinese history.

The Koreans next sailed to Tangp’o, where a garrison of 300 Japanese samurai was stationed. Japanese warships crowded the Tangp’o wharf, including nine large vessels and 12 smaller ones. The Korean fleet arrived at Tang’po at 10 in the morning of June 2. There was one particular ship within the harbor that seemed to stand out above all the rest, a large warship probably of the adake-bune class. A large pavilion-tent was pitched on its decks, richly embroidered and emblazoned with the Chinese character Hwang (“Yellow”) on it.

The pavilion curtain was parted just enough to see the occupant, a man of obvious importance sitting smugly near a red parasol. He was Admiral Kurushima Michiyuki, whose relative youth was offset by his splendid yellow brocade kimono and gilded headdress, the latter sparkling when he finally emerged from his luxurious cocoon.

The Koreans attacked, the kobukson in the van as usual. Kurushima’s flagship was the primary target, a wooden “mountain” that featured a triple-deck tower on the prow. The cannon mounted in the turtleship’s dragon figurehead opened fire, causing its mouth to spew flames and smoke just like the mythical beast it represented. Cannonballs lanced into the Japanese flagship, and arrows pelted its decks. Kurushima was mortally wounded by a barbed shaft, and when Koreans boarded he was dead. A Japanese version of the story claims he committed suicide—seppuku—lest he be captured before he died.

The Japanese seem to have lost heart when Admiral Kurushima died. The Japanese ships were captured or destroyed, and those invaders that survived took to their heels and fled into the mountains. A young Korean woman named Ok-tae had been forced to be Kurushima’s concubine, and once liberated she gave a detailed description of life aboard a Japanese flagship. The flagship also yielded some spoils, including an exquisite golden fan that had been given to General Kokonori by none other than Toyotomi Hideyoshi himself.

When the Tangp’o battle was over, a patrol boat came in and informed the Admiral that some 20 Japanese vessels and an indeterminate number of smaller boats were in the vicinity. Yi ordered a pursuit, but when the Japanese ships caught sight of the approaching Koreans they turned tail and scattered. It seems that Yi Sun Shin’s growing reputation was beginning to effect Japanese morale.

Korea Forms “Righteous Armies”

On June 4 Left Cholla Admiral Yi joined forces with his counterpart, Right Cholla Admiral Yi Ok-ki, boosting the total number of the Korean fleet to 51 ships. Tanghangp’o Bay, where 26 Japanese ships were located, was the next objective. Because the bay was too narrow for maneuvering, Yi Sun Shin pretended retreat to lure the enemy out. Once again, the Japanese took the bait, and once again, the Koreans scored a smashing victory.

Meanwhile Japanese oppression sparked a guerrilla movement among the Korean people, who formed uibyong, “righteous armies,” to harass the invader. In a sense, the Japanese were victims of their own success. They had advanced so far and so fast that their supply lines were dangerously overextended. For example, a large army under General Koninshi Yukinaga and So Yoshimoto was at P’yongyang, roughly 300 miles northwest of the forward Japanese supply base at Pusan. They needed ammunition, supplies, and reinforcements before they could advance the Imjin War into China.

Toyotomi Hideyoshi decided the best course of action was to supply his northern armies by sea. The route would start at Pusan then skirt the southern and western coasts of Choson into the Yellow Sea. Supplies and reinforcements could be funneled into P’yongyang via the Taedong River. It was an admirable plan, at least on paper, because it avoided increasingly risky land routes. But it was clear that before the scheme could be implemented the sea-lanes had to be cleared of Korean naval interference. As Yi Sun Shin had foreseen, the stage was set for a major confrontation, a sea battle that might determine the fate of Choson/Korea.

Yi prepared for the coming clash as best he could, consulting with Cholla Right Admiral Yi Ok-ki and Kyongsang Right Admiral Won Kyun about future courses of action. The three admirals merged their forces, which produced a combined armada of 56 ships. Because contact with the enemy was imminent, Yi Sun Shin took what time remained to forge three disparate commands into one fighting unit. If the kobukson was the heart of the Korean fleet, Yi Sun Shin was its soul.

The Korean fleet weighed anchor and arrived at Tangp’o on the evening of July 7. A local farm servant named Chon-son told Yi Sun Shin a large Japanese fleet was anchored in the Konnaeryang Strait, a narrow waterway between Koje Island and the Tongyeong peninsula.

Admiral Yi wasted no time in acting on this information, and the fleet soon left Tangp’o in search of the enemy. Sure enough, a large Japanese armada of 82 ships was anchored in Konnaeryang Straits. The invading force was led by Admirals Wakizaka Yasuharu, Kato Yoshiaki, and Kuki Yoshitaka. They were not career naval officers, but daimyo (feudal lords) with varying experience at sea in Japan.

The Plan to Trap Japan’s Navy

Yi Sun Shin had a keen eye for topography, and one glance told him to be wary of the Konnaeryang Straits. Hidden shoals lurked below the waterline, and submerged rocks waited to rip the bottom out of any unsuspecting vessel. Above all the straits were narrow, about 400 yards wide, and plainly too confined for the maneuvers he was planning to spring on the Japanese.

The enemy had to be lured out into open water, where Yi could spring a trap just west of Hansando (Hansan Island). As the admiral explained later, “I adopted the tactic of luring the enemy out to sea in front of Hansando where we could capture his vessels and slaughter his men in one strike, because Hansan lies between Koje and Kosong, separated all around from land to swim to, and even those who landed [there] would die of starvation.”

The wily Korean admiral sent six ships into the strait, decoy vessels that would act “surprised” when they encountered the Japanese, and beat a hasty retreat. The six Korean ships seemed easy prey, and the Japanese Admirals’ predatory instincts won out over common sense. The Japanese weighed anchor in pursuit, the squadron under Wakizaka Yasuharu leading the way.

The six decoy vessels managed to evade their pursuers, reaching the safety of the main Korean fleet. The Japanese armada was now in the open, advancing in battle formation in the blue waters of Hansan Bay. Everything was going according to plan; now it was time to spring the trap. Yi Sun Shin hoisted a blue flag, his signal for the fleet to adopt the crane wing formation. This was Yi’s invention, a tactical innovation that enveloped the enemy like the enfolding feathers of a bird’s wings.

“Cheo-ra!”

When the last ship wheeled into formation Admiral Yi shouted “Cheo-ra!” (Charge!) and the entire fleet went forward. Oars churned the blue waters into a white foam, and drums beat a pounding tattoo that merged with the sounds of battle. The right wing, left wing, and center moved forward in a line-abreast formation, not the line-ahead formation more familiar in 18th-century naval warfare. The Japanese suddenly found themselves confronted by a long concave wall of ships, a wall that now erupted into smoke and flame as ji (earth) and hyun (black) class cannon began to open fire.

The cannonballs soon found their mark, smashing Japanese ships so hard some broke into pieces. Still reeling from this savage pummeling, enemy vessels were set alight by fire arrows launched by both archers and cannon. The turtleships were in the center, artillery-firing wooden fists that bludgeoned their way through the Japanese fleet in order to open a path for others to follow. The kobukson were chillingly effective, careening through the Japanese and leaving a trail of burning and shattered hulks in their wake.

The “bull in a china shop” methods of the turtleships caused the Japanese to ruefully dub them mekurabune or “blindship.” In other words, their fearless attacks were like that of a blind warrior, striking out in all directions. Japanese ships had few cannon, since grappling and boarding was the accepted tactic among Hideyoshi’s admirals.

A turtleship’s upper deck was completely roofed over, the thick pine planks studded with iron spikes like a porcupine’s quills. To further deceive the enemy, straw mattresses camouflaged the spikes; unwary Japanese boarders would be impaled as they jumped aboard. Apparently when in the “attack” mode a turtleboat’s sails were taken down and its two masts lowered into a recumbent position. The kobukson was propelled by oars, four rowers to an oar. In normal occasions, only two rowers maintained the stroke, but in battle all four worked in union. Each quartet was directed by an officer.

Japanese Samurai Had Little Protection Against Korean Arrows

The Japanese fleet was soon in disarray, and though individual ships fought bravely, it was clear the momentum was with the Koreans. Korean ships vied with one another to board and capture striken enemy craft. Inspired by Admiral Yi, crews went forward with the Korean victory cry of “Cheon-se!” A magistrate named Kwon Chun was so eager to come to grips with the enemy, his ship was the first to penetrate the Japanese line. Kwon and his men boarded a large Japanese ship, beheading 10 samurai during the capture and liberating a Korean prisoner found aboard for good measure.

Columns of smoke rose into the sky, each black column marking the flaming remains of a Japanese warship. Most samurai aboard ship wore minimal protection, just a do (body armor) and a helmet. They even fired their matchlocks from a sitting, not standing, position in battle. All these customs were precautions against falling overboard, because even the bravest samurai feared drowning. The scanty armor offered little protection against the clouds of Korean arrows that thudded into their bodies.

After several hours Yi Sun Shin’s victory was complete. Burning wreckage bobbed about, and parts of the once blue waters were dyed red with blood. The Korean fleet had destroyed 47 enemy ships and captured 12. Perhaps 14 Japanese ships escaped the debacle, including the flagship of Admiral Wakazawa. Wakazawa was lucky to survive at all; his ship was badly battered, and his armor had been “hit many times with enemy arrows.” Japanese records admitted he owed his survival to the fact his flagship was a hayabune (fast ship).

When all seemed lost, some Japanese officers committed seppuku (suicide) in the time-honored samurai tradition. Admiral Wakazawa’s lieutenants Wakisaka Sabee and Watanabe Shichiuemon chose to disembowel themselves with swords rather than bear such an ignominious defeat. A few hundred Japanese survivors managed to swim to the temporary safety of Hansan Island, but their captain, Manabe Shibayin, killed himself.

Korea Crippled Hideyoshi’s Grandiose Plans

Admiral Yi followed Hansan Island with a victory at Angolp’o. Flushed with success, the Koreans now attacked the greatest prize of all, Pusan. Pusan was the main enemy port in Choson/Korea, a logistical base through which supplies and reinforcements from Japan were funneled north. Unfortunately, Pusan was too heavily defended for Yi to achieve the decisive victory he so desired. In spite of this, the Koreans managed to inflict heavy damage on the enemy, sinking around 130 ships during the course of the operation.

On land the Japanese were faring no better. Finally alert to the great danger the Japanese posed, the Chinese sent a 50,000-man army to help the Koreans. After a series of battles the Japanese retreated to enclaves in southern Choson. The war sputtered out, replaced by a series of protracted peace talks, and ended in 1598.

The naval operations of May through September during the Imjin War proved Yi Sun Shin to be one of the great captains of military history. The Battle of Hansan Island was the Trafalgar or Salamis of Asia, a decisive encounter that saved China from invasion and Choson from permanent occupation. During the four-month period of operations, approximately 300 Japanese ships were destroyed or captured, severely crippling Hideyoshi’s grandiose plans of conquest. It is with good reason that Yi Sun Shin is a Korean national hero, honored with the title Ch’ungmukong (Lord of Loyalty and Chivalry).

Great read! Informative, exciting, and well-written.