by A.B. Feuer

Following the Civil War, the United States saw enormous industrial progress. A sense of nationalism also developed, and public opinion was continually enlisted behind an aggressive foreign policy.

Media Fans The Flames Of Nationalism During Cuban Revolution

During the 1880s the American news media exploited the Cuban revolution to the hilt. Spain was depicted as a decadent nation, and the policies of the Spanish monarchy were pictured as cruel, oppressive, and “too close to American shores.” All the elements of “good copy” were at hand and the rag sheets of Hearst and Pulitzer made the most of it.

The sinking of the USS Maine in Havana Harbor on February 15, 1898 was the catalyst that brought it all together. Sylvester Scovel of the New York World wrote: “Whether Spanish treachery devised, or Spanish willingness permitted this colossal crime, Spain is responsible for it. No number of millions of mere money could compensate for the cowardly slaughter of these brave men and the treacherous destruction of a noble ship. The only atonement at all adequate for such a deed would be the liberation of Cuba.”

Spain Downplays American Naval Influence

On February 26, Spanish Admiral Pascual Cervera was aboard his flagship at Cartagena, Spain. He wrote a letter to the Spanish marine minister, Segismundo Bermejo, reporting the seriousness of the Cuban situation, and the dim prospects of defending an island three thousand miles from Spain.

Bermejo was angered by Cervera’s assessment of the situation. The minister assured the admiral that American naval strength in the Caribbean had been vastly overestimated, and that the USS Oregon, one of only four first-class battleships in the American fleet, was anchored at San Francisco. Bermejo argued that the Spanish Pacific Squadron constituted a threat to American West Coast ports and shipping. He was certain that the Oregon would remain in California. But, he told Cervera, even if the U.S. Navy Department decided to send the Oregon to the Caribbean, it would mean steaming the battleship 16,000 miles around the southern tip of South America. The voyage would be long and difficult, and before the Oregon completed the trip, Spain would have concentrated her naval forces at Cuba to defend the island.

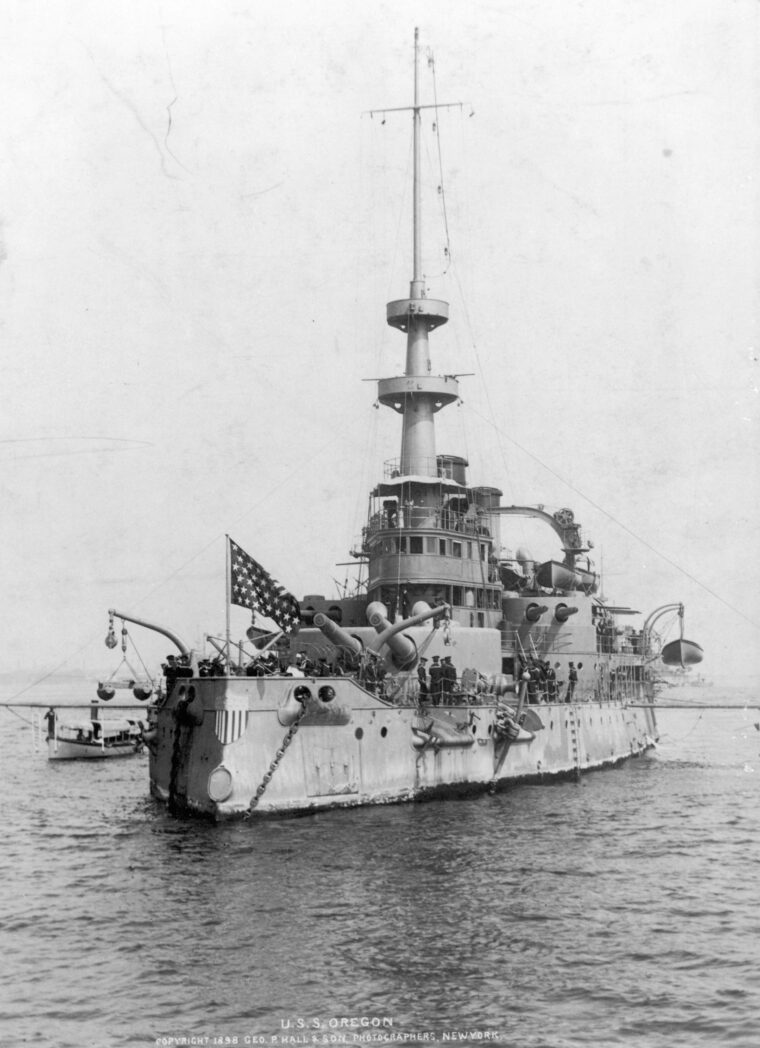

The Oregon was the last of four Indiana-class battleships authorized by Congress, and the only one built on the West Coast. Her contract was awarded to the Union Iron Works of San Francisco in November 1890, and she was commissioned on July 25, 1896.

Oregon State-Of-the-Art Warship

The Oregon was the newest man-o’-war afloat and incorporated all the latest naval innovations. The battleship was 351 feet in length and 69 feet abeam. Her main battery consisted of four 13-inch guns in double turrets and eight 8-inch guns. The turrets were hydraulically operated, while those on her sister ships were powered by steam.

In addition to her heavy armament, the Oregon carried 20 six-pounders, evenly distributed from bow to stern. She also mounted eight one-pounders and six Whitehead torpedo tubes. She displaced 10,000 tons and had a cruising radius of eight thousand miles. An armored belt, 18 inches thick, ran two-thirds the length of her hull at the waterline.

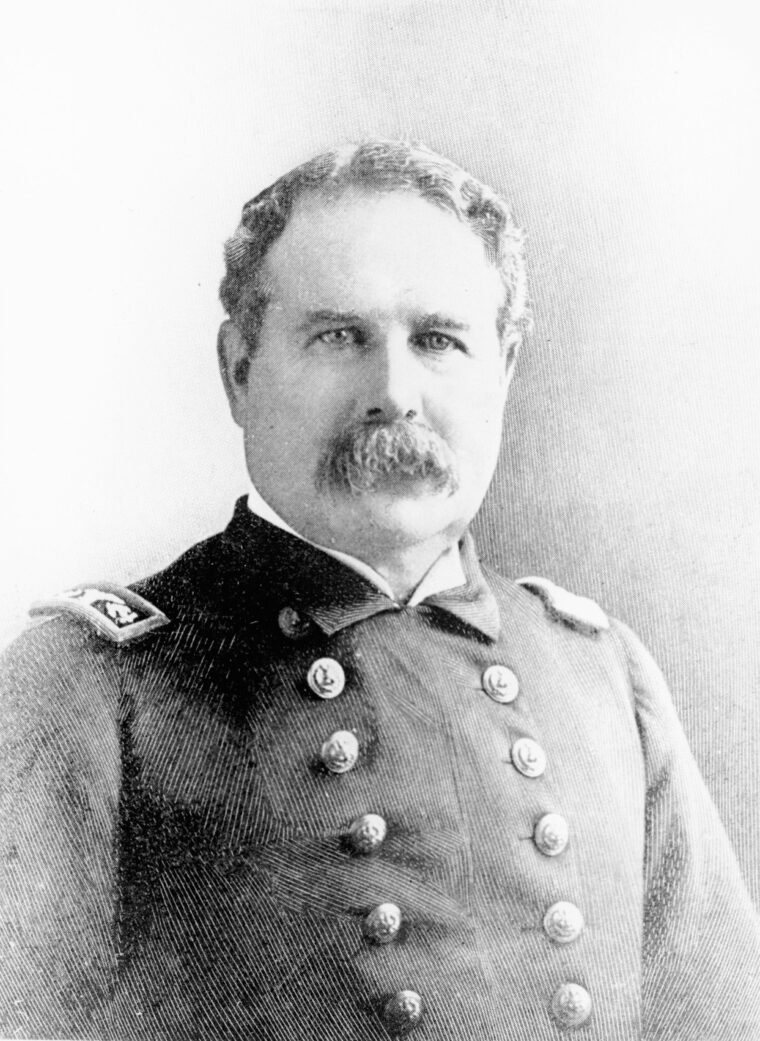

When the Maine incident occurred, Oregon was based at San Francisco and under the command of Captain Alexander H. McCormick. As the national clamor for war increased, McCormick received orders to take his ship to Callao, Peru and await further instructions.

Oregon Changes Captains At The Last Minute

Secretary of the Navy John D. Long theorized that in case of open hostilities, the Oregon would be in an ideal position to be sent to either the Philippines or the Caribbean.

The battleship was hurriedly coaled and provisioned. The sailing date was scheduled for March 18, but then McCormick fell suddenly ill. The voyage could not be postponed, however; a replacement had to be found—and fast.

Captain Charles E. Clark, commanding officer of the monitor Monterey, was stationed at San Diego, when he received a cable from the Navy Department ordering him to assume command of the Oregon. Clark arrived at San Francisco on March 17, and at 8 o’clock on the morning of the 19th, the battleship hoisted anchor and passed through the Golden Gate.

Spanish Have Sights On Oregon

Oregon carried a crew of 30 officers and 438 men. The battleship rode low in the water—packed with 1,600 tons of coal, 500 tons of ammunition, and enough supplies to last several months.

While Oregon steamed south, Navy Secretary Long made his momentous decision. He would send the battleship to join Admiral Sampson’s Atlantic Fleet. Segismundo Bermejo had made a serious error in judgment.

On March 26, when Oregon was almost halfway to Peru, Long received a report that the Spanish torpedo boat Temerario had left Montevideo, Uruguay—destination unknown.

Long worried that the Spanish vessel might be heading for the Straits of Magellan to intercept the Oregon. He was doubly concerned for the gunboat Marietta. She had left the West Coast several days before the battleship and was also bound for the Caribbean.

Tropics And Hot Water Make For Tough Conditions Onboard

Theodore Roosevelt, Assistant Secretary of the Navy, suggested that it might be safer to route Oregon completely south of Cape Horn. He felt the battleship would be at a tactical disadvantage in the narrow waters of the straits. The decision, however, would be left up to Captain Clark.

The Oregon continued to plow south at 12 knots. Three of the battleship’s four boilers had a full head of steam. Clark wrote: “Our run from San Francisco to Callao was uneventful. But as we approached the tropics, life below decks became almost intolerable from the weather, plus the heat that was generated by the ship’s boilers.

“When Chief Engineer Milligan informed me that he thought we should never use salt water in the boilers, I felt it was asking too much of the endurance of the crew. It not only meant reducing their drinking supply, but that the quantity served would often be so warm as to be quite unpalatable. However, when I explained to the men that salt water in the boilers created scale, and scale would reduce our speed and might impair our efficiency in battle, the deprivation was borne without a murmur.”

Not Able To Rest Easy, Even In Port

On the afternoon of March 27, someone saw smoke coming from one of Oregon’s coal bunkers. After four hours of digging through the compartment, the burning coal was reached and extinguished. The cause of the fire—spontaneous combustion.

At 5 in the morning of April 4, Oregon dropped anchor in the harbor at Callao, Peru. The battleship had made a continuous run covering 4,112 nautical miles in 16 days and burned 900 tons of coal.

While at Callao, Clark received a dispatch from the Navy Department warning about the Temerario. Clark reportedly said, “I am ready to sink the Spanish ship—war or no war!”

But the captain of the Oregon also had other concerns. Because Peru was a Spanish-speaking country, he was aware there might be sympathetic Spaniards in the area. Clark ordered two steam cutters to patrol the harbor 24 hours a day. A double watch was posted at all times, and sharpshooters were stationed in the fighting tops.

The Next Leg Of The Voyage Begins

Oregon’s crew worked day and night loading coal, water, and provisions. Payday was April 6, but there was no shore leave. Every man was needed to get the ship ready for the next leg of her journey.

At 4 am on April 7, Oregon weighed anchor and set a course for the Straits of Magellan. Over 1,700 tons of coal had been loaded in her bunkers, and a hundred more tons packed in sacks on the deck. A thick layer of coal dust covered the sides of the battleship, but there was no time to wash it off. The Oregon would remain a dingy-looking vessel for a long time.

Captain Clark fired up the fourth boiler on April 9, and speed was increased to 14 knots. He ordered target practice. Empty boxes and barrels were tossed over the side, and all guns were tested for operating efficiency.

Storms Pummel Oregon

As the Oregon continued south, the weather began to change for the worse. The heavily laden warship continually dipped her bow into mountainous waves and struggled against gale- force winds. Oregon pitched and rolled in the raging ocean. At times her deck disappeared completely under solid sheets of water that swept over the vessel. Whenever the battleship’s bow plunged beneath the churning sea, her propellers lifted clear of the water and whirled around at tremendous speed, shaking the ship like a quivering leaf. The strain on both hull and machinery was enormous, but Captain Clark shouldered the responsibility and raced on ahead.

On April 16, Oregon reached the western entrance to the Straits of Magellan. Clark wrote: “Minutes after entering the straits, a violent storm struck us. The wind-driven rain obscured the precipitous rockbound shores, and with night coming on, it seemed inadvisable to proceed. The ship running before the gale as she was made it almost impossible to obtain correct soundings, and making a safe anchorage was therefore largely a matter of chance. I decided to anchor as the lesser risk.”

Oregon dropped two anchors, which plummeted 50 fathoms before finally grabbing the ocean floor.

“Mountain After Mountain Of Glacier”

At daybreak the next morning, the battleship was once again under way. This time she fought a blinding snowstorm through the narrowest passage of the straits—many places less than a mile in width. With sheer cliffs on either side, and unknown water depth below, it was not a place for faint hearts.

By midday, however, the weather cleared and the crew of the Oregon was treated to a breathtaking landscape. One sailor wrote: “I have never seen such beautiful wild nature in all my travels. There is mountain after mountain of glacier, and they seem to have all the colors of the rainbow. It was cold, and the ice sparkled like diamonds. We soon passed the wrecks of two steamers that had left their bones to mark the perils of the passage.”

At 6 pm, the Oregon anchored at Sandy Point, Chile. Captain Clark knew that the Spanish torpedo boat had plenty of time to reach the straits and might be waiting for the Oregon when she entered the Atlantic.

The Endless Task Of Hoisting Coal Aboard

Clark ordered the battleship cleared for action and all guns manned and loaded. The two cutters were also put back on patrol. In addition, around midnight, the Marietta arrived; her orders were to escort the Oregon up the east coast of South America.

The following morning, Captain Clark went ashore to make arrangements for fuel and supplies. The merchant from whom he purchased the coal was very suspicious of the Americans. Clark reported: “The coal had to be removed from an old hulk in which wool had been stored on top. It was by no means an easy job. The merchant added to delays in handling by insisting that the hoisting buckets be frequently weighed. Finally, Murphy, one of the boatswain’s mates, relieved the growing exasperation by calling out, as a loaded bucket reached the deck, ‘Here! Lower again for another weigh—there’s a fly on the edge of that bucket!’”

The Oregon needed 800 tons of coal to fill her bunkers and the job seemed to take forever. The crew worked day and night hauling the small containers of fuel up the sides of the battleship. Provisions, such as meat and canned goods, were tossed in the same buckets and hoisted topside. Everything was covered with coal dust.

Out Into The Turbulent Waters Of The South Atlantic

Captain Symonds of the Marietta also had trouble with the merchant. He had been allowed to take on only 40 tons of coal. Clark went on the warpath. He told Symonds to move his vessel alongside the coal ship and load up the gunboat.

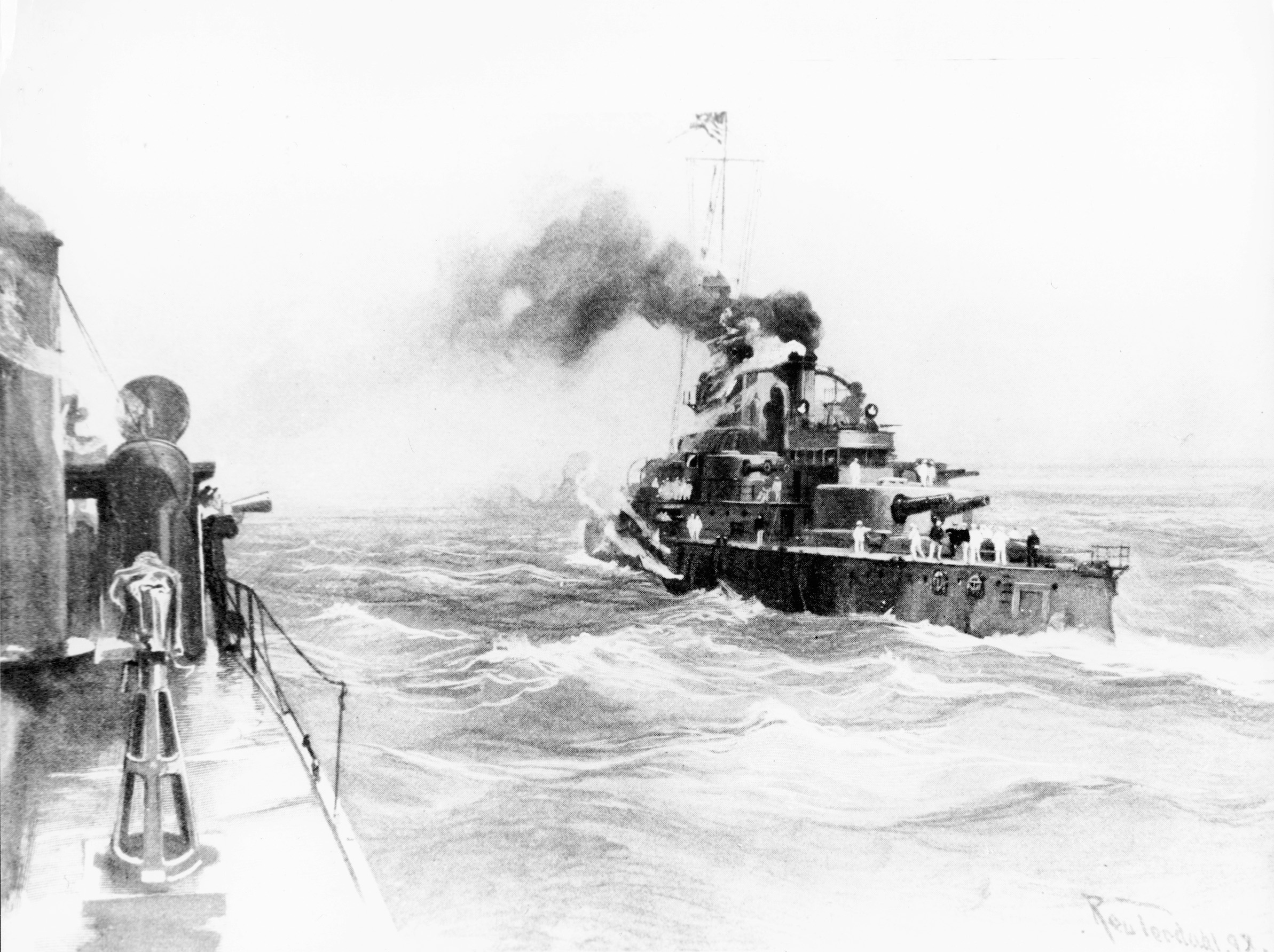

Finally, at 6 in the morning on April 21, the Oregon and Marietta steamed out of Sandy Point and headed for the turbulent waters of the South Atlantic. Marietta led the way, but she was the slower vessel and the battleship was forced to reduce speed. After leaving the straits, Captain Clark sounded general quarters, “just to shake the boys up,” and the Marietta threw barrels over the side for target practice.

The Oregon had been stripped for battle during her stay at Sandy Point. But after five days at sea in the rough South Atlantic, the tension of the voyage was beginning to take its toll on the frazzled nerves of the tired crew. One grumbling sailor stated: “Boxes, benches, and all extra mess chests have been stowed away. We have no place to sit down, except on deck, and then have to let our feet hang over the side. The men can’t seem to get enough water, and the cook’s sourbread would make good shrapnel for clearing the decks.”

Crew Learns America Is At War

When the Oregon neared Rio de Janeiro, the battleship dashed ahead of the Marietta and raced for the port at top speed. Clark anchored in Rio Harbor at 3 in the afternoon of April 30.

A dispatch boat immediately pulled alongside the Oregon with Navy Department telegrams. Clark was notified that the United States had been officially at war with Spain since April 25.

Captain Clark solemnly read the war message to his crew. But the pressures of 42 days at sea were too much for the men to take the news lightly. Lieutenant E.W. Eberle recalled: “All hands were anxious for information, and the shouts that greeted the news that war had been declared were thrilling and memorable. In a few moments our ship’s band was on deck, and between continual rounds of cheers, the strains of ‘The Star Spangled Banner’ and ‘Hail Columbia’ drifted over the bay.

“Remember the Maine!”

“The crew uncovered and stood at attention during the playing of the national anthem. More cheering followed, along with the inspiring battle cry ‘Remember the Maine!’ The men then turned to the coal barges and worked as they had never worked before.” Marietta arrived at about 7 o’clock and another celebration rocked the harbor.

Clark was also informed that the Temerario was probably heading for Rio. He wrote: “This was disturbing information. If the torpedo boat should arrive, and it had an enterprising commander, I felt he would not hesitate to violate the rights of a neutral port—if by doing so, he could put the Oregon out of action.”

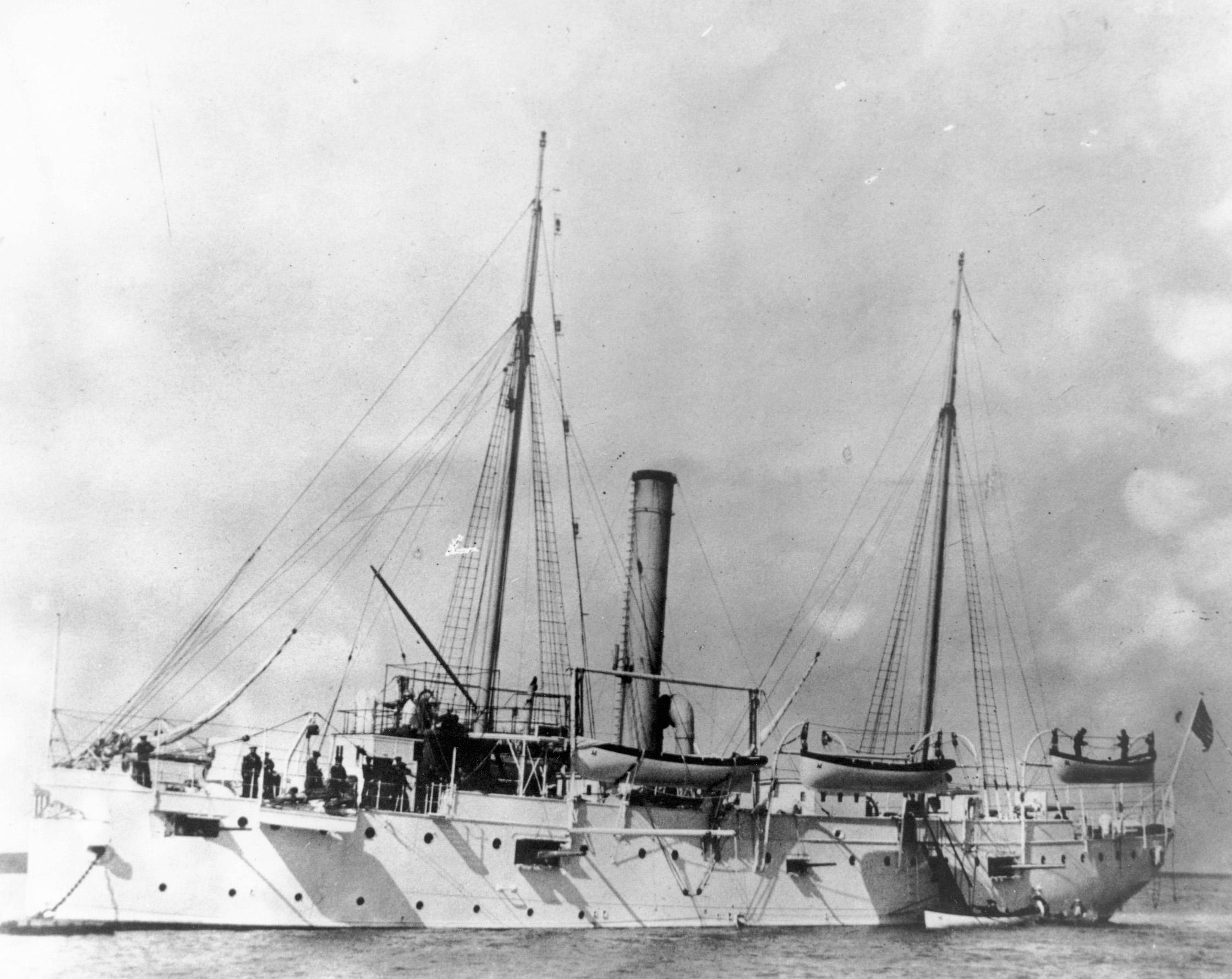

On May 2, the American consul came aboard the Oregon with news that four Spanish cruisers and three torpedo boats had sailed from the Cape Verde Islands—destination unknown. He learned also that Secretary Long was reluctant to risk a valuable ship like the Oregon in case the Spaniards were intending to intercept the battleship near Rio. Long had purchased an auxiliary cruiser, the Nictheroy, from the Brazilian government, and both the Marietta and Nictheroy were assigned to accompany the Oregon on the final leg of her journey.

Unsure About The Direction And Intentions Of The Enemy

Captain Clark did not agree with the Navy Department. He believed the Spanish fleet was headed for the Caribbean, and if that was the case, his battleship’s presence in the West Indies was essential. He said: “If the Spaniards were heading for Rio, they would arrive in the vicinity before we could get away. But it did not seem likely to me that the enemy would make this attempt to cut us off, especially if there was the possibility of missing us altogether.”

In event that the Spanish were close to Rio and attempted to engage the Oregon, Clark intended to make it a running fight. He was confident that, by steaming at full speed, he would be able to string out his attackers and fight them separately.

On May 4, Oregon and her two escorts steamed out of Rio de Janeiro. It soon became evident that the accompanying vessels were too slow for the battleship, and Clark worried that they would be more of a hindrance than help in a battle. He ordered the Marietta and Nictheroy to Cape Frio, and the Oregon headed north alone.

Tense Crew On Lookout For Suspicious Vessels

Captain Clark called his crew aft and explained the situation. He read them the dispatches concerning the strength of the Spanish squadron and its unknown whereabouts. Clark added: “Should we meet, we will at least lower Spain’s fighting efficiency upon the seas. Her fleet will not be worth much after the encounter.” The men gave their captain a round of cheers. They were ready for the Spaniards and confident of victory.

Clark posted lookouts around the clock. They were authorized to sound the alarm if any ship was sighted—without waiting for orders.

At 5 in the morning of May 7, the general- quarters alarm sent the anxious crew to their battle stations. A lookout had spotted a strange vessel in a rain squall. This turned out to be, however, a vintage sailing ship. But as long as the men were already at their gun posts, target practice was held to relieve the anxiety and frustration of the early-morning wake-up call.

Ship Gets Supplies And A Fresh Coat Of Paint

The following day, Oregon steamed into Bahia, Brazil. Captain Clark requested permission to anchor in the harbor. He used the excuse of “engine trouble,” and notified the port authority that the battleship might be at Bahia for several days. In reality, the purpose of the stopover was to apply a fresh coat of warpaint and replenish the ship’s coal and water supply. Clark’s comment of “several days” was intended to deceive any Spanish agents lurking in the vicinity.

While his crew was busy wire-brushing and painting the Oregon, Clark sent a cable to the Navy Department: “Much delayed by Marietta and Nictheroy. Left them near Cape Frio with orders to come here [Bahia], or beach if necessary to avoid capture. The Oregon can steam fourteen knots for hours, and in a running fight could beat off and even cripple Spanish fleet. With present amount of coal on board we will be in good fighting trim and can reach the West Indies. Whereabouts of Spanish fleet requested.”

Secretary Long replied: “Proceed at once to West Indies. No authentic news of Spanish squadron—avoid if possible.”

Hunted Oregon Sneaks Out Of Port

It was very probable that the Spaniards were close by. Intelligence reports revealed that the enemy ships had been at Curaçao four days previously—only 500 miles from Bahia.

At 11 on the night of May 9, the Oregon sneaked out of the Brazilian port and headed at full speed for Barbados, arriving at Bridgetown at 2 in the morning, May 18.

Clark was told that, due to neutrality regulations, he had to leave within 24 hours. The American consul sent a cablegram to the United States announcing the Oregon’s arrival, while the Spanish consul sent the same news to the governor of Puerto Rico.

Numerous unconfirmed rumors had been circulating in Bridgetown, including a story that the Spaniards were waiting outside the harbor for the Oregon to emerge. Moreover, by this time, the enemy fleet had swelled to 18 vessels.

Oregon Sets Its Sights On Florida

Oregon rapidly loaded 250 tons of coal and left port at dark the next night. Owing to the danger of running into a trap, Clark decided to make a detour instead of taking the direct route through the West Indies. He wrote: “With lights showing, we ran for a few miles toward the passage between Martinique and Santa Lucia. Lights were then extinguished, and we headed back toward Barbados. Our course swung clear of the Virgin Islands, then off the Bahamas, and finally for the Florida coast.”

During the two days the Oregon was anchored at Bridgetown, Clark was told that units of the U.S. Atlantic Fleet were concentrated near the Dry Tortugas and at Hampton Roads. After conferring with his officers, the captain decided to set his course for Jupiter Inlet, Florida, where he could telegraph the Navy Department for further instructions.

The Jupiter lighthouse was sighted on the early evening of May 24. A whaleboat was sent ashore, and the news that the nation had breathlessly been waiting to hear was flashed to Washington: “Oregon arrived at Jupiter Inlet. Have enough coal to reach Dry Tortugas in 33 hours—Hampton Roads in 52 hours.”

The Grueling Odyssey Of Oregon Comes To An End

Secretary Long cabled an immediate reply: “If ship is in good condition go to Key West—otherwise Hampton Roads. The Navy Department congratulates you on your safe arrival, which has been reported to the President.”

There was no hesitation on the part of Captain Clark. The Oregon and its crew had jelled into a powerful and efficient fighting machine. The men were hell-bent to get at the Spanish, and the sooner the better. The battleship dashed for Key West at top speed.

About 4 am on May 26, Oregon was only a few miles from landfall. Suddenly a small dark object was spotted on a collision course. General quarters sounded, and as the weary crew scrambled to their battle stations, many wondered whether this trip—which seemed to last forever—would ever end.

The “dark object” turned out to be the revenue cutter Hudson. She had been detailed to escort the battleship into port.

After 68 grueling days, the odyssey of the Oregon had finally ended.

Long Journey Makes Strong Case For Canal

The fact that the battleship could make such a hazardous journey, and arrive at her destination safe and sound, testified to both the excellence of the vessel and the efficiency of her crew.

ButOregon’s famous voyage had significance far beyond the part she played in the Spanish-American War. The trip itself advertised to the public as well as to the military, as nothing else could have, the strategic necessity for building a canal across the Central American isthmus. A canal would have allowed the Oregon to steam 4,000 miles rather than 12,000. Accordingly, the United States entered into a treaty in 1901 to build a canal, one wide enough to accommodate battleships.

The cruise of the Oregon was described as “unprecedented in battleship history, and one which will long preserve its unique distinction.” Every American was stirred by the excitement of the adventure, and a few expressed their emotions in verse. John James Meehan, in his poem “The Race of the Oregon,” wrote:

“When your boys shall ask what the guns are for,

Then tell them the tale of the Spanish War,

And the breathless millions that looked upon

The matchless race of the Oregon.”

I am attempting to prove the military service of Cyrus D. Brockway who is said to have served on the Battleship Oregon during the Spanish/American War.

Would you happen to have any documents to support this?

Mike Rowley

1825 NW 129th St, Clive, IA 50325

(515-975-0498

MJR1825@gmail.com