by David A. Norris

Union General Benjamin Butler was baffled. Every night a picket guard went to an outpost 1½ miles from Fort Monroe, Virginia. The soldiers departed for their shift perfectly sober, yet when they returned to the post the next morning they caused trouble “on account of being drunk.” Investigations failed to reveal the source of their whiskey. Searches of canteens and gear turned up nothing suspicious. But there was one odd thing about the detachment: someone in Butler’s command noticed that the men always held their muskets straight up in a peculiar manner. The mystery unraveled when their muskets were examined. “Every gun barrel,” wrote Butler, “was found to be filled with whiskey.”

[text_ad]

Excessive drinking was a constant problem in both armies during the Civil War. “No one evil agent so much obstructs this army as the degrading vice of drunkenness,” wrote Union Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan in February 1862. “It is the cause of by far the greatest part of the disorders which are examined by court-martial.” The complete abolition of alcohol, he believed, “would be worth fifty thousand men to the armies of the United States.” And across the Mason-Dixon Line, the Norfolk Day-Book complained that Confederate enlisted men and officers in the vicinity were drinking whiskey “in quantities which would astonish the nerves of a cast-iron lamp-post, and of a quality which would destroy the digestive organs of an ostrich.”

Whiskey the Drink of Choice for Most Soldiers

Many if not most soldiers were already well acquainted with alcohol from the antebellum era. Whiskey was far and away the most popular drink in 1861. Often made from corn instead of grain, it was distilled at countless locations across the country. Popular nondistilled drinks included cider and beer. Cider, made from apples, was more common, but beer was quickly growing in favor, its rise fueled by the steady German immigration into Northern states.

Low-grade whiskey carried with it the threat of poisoning the drinker, so makers might start with clear alcohol, water it down, and then doctor the mixture to simulate the color and flavor of the real thing. Chewing tobacco, for example, helped approximate the amber tint of whiskey or brandy. Harsher ingredients added the bite that drinkers expected in their whiskey. An 1860 inspection of liquor samples in Cincinnati found whiskey containing sulfuric acid, red pepper, caustic, soda, potassium, and strychnine. It was no wonder that “rotgut” was the most prevalent nickname for cheap liquor during the era.

Countering the growth of alcohol consumption was the temperance movement, which sought to make all forms of alcoholic beverages illegal. Maine enacted a prohibition law in 1851. Several other states or territories passed dry laws in the following years. In most cases, these laws were repealed or overturned within a short time. Per capita consumption peaked in 1830 at an equivalent of 7.1 gallons of alcohol annually. A swift decline followed, with the annual per capita figure dropping to 2.53 gallons by 1860.

“Spirit Rations” Abolished

Alcohol still had an official presence in the U.S. Army in 1861. A daily spirit ration for American soldiers had been abolished in 1832, but officers were permitted to issue special servings of whiskey to relieve fatigue and exposure. Soldiers, naturally, had countless sneaky ways to obtain whiskey. While diligent officers could restrict the flow of whiskey into camp, soldiers could still drink when they received a pass to leave camp. In the Confederate Army, the phrase “running the blockade” meant slipping in and out of camp for illicit purposes, usually involving alcohol.

On February 27, 1862, the Confederate Congress passed a law allowing President Jefferson Davis to suspend habeas corpus and declare martial law in areas threatened by the enemy. Immediately, martial law was declared in Portsmouth and Norfolk, Virginia, followed by Richmond on March 1. Richmond came under control of the provost guards commanded by Brig. Gen. John H. Winder, who prohibited the manufacture of liquor and closed the city’s saloons. By then liquor sales had caused so much trouble and crime among Confederate soldiers and civilian that many in Richmond welcomed martial law. Winder also barred rail shipments of whiskey into the Confederate capital. Apothecaries were allowed to dispense liquor only with a doctor’s prescription.

Martial law did not stop the distribution of whiskey, but merely drove it underground. There were still countless cases of drunk and disorderly behavior, as well as arrests for illegal sales of alcohol. Corruption flourished among the provost guards, some of whom forged prescriptions for alcohol. After obtaining the liquor, they then arrested the apothecaries who had dispensed it, thus adding insult to injury.

A ‘Creature Comfort’ Care Package From Home

A great deal of whiskey was sent to army camps on both sides by well-meaning relatives back home. It was a common practice, especially among the Union soldiers, for families to send their loved ones packages of fresh, canned, or smoked food and other small creature comforts. Commanding officers quickly realized that a great deal of whiskey was also being smuggled into camp inside these care packages. General Butler later testified before Congress that a search of an Adams Express Company depot yielded 150 different packages of liquor in crates and boxes on their way to his command.

Every parcel intended for a soldier had to be opened and inspected by officers of his regiment or brigade. Union Private John D. Billings, in his classic memoir Hardtack and Coffee, recalled, “There was many a growl uttered by men who lost their little pint or quart bottle of some choice stimulating beverage, which had been confiscated from a box as contraband of war.” Billings noted some ingenious ways that innocent-looking gifts concealed whiskey. One favorite ruse was hiding a bottle of whiskey inside a well-roasted turkey. Whiskey bottles also came into Billings’ camp in tin cans of small cakes or in loaves of bread with holes cut in the bottom.

Smuggling whiskey in legitimate-looking containers with false labels was a common practice. A helpful sutler showed Butler several little bottles that supposedly contained hair oil packaged by a New York City firm. Instead, each bottle contained half a pint of whiskey, with a little olive oil on top. The bottles were sold wholesale at eight cents each, but soldiers paid 25 cents for them in camp. The distributor claimed to have sold thousands of such bottles at Fort Monroe.

Alcohol Restrictions Lead to Officer Impersonation

In February 1863, the Union guard boat Jacob Bell searched the supply schooner Mail at Alexandria, Virginia. Aboard the schooner were 428 dozen cans labeled “milk drink” packaged by Numsen, Carroll & Company, a Baltimore firm. Upon closer inspection, Lt. Cmdr. E.P. McCrea learned that the milk drink was actually “villainous eggnog.” Commodore Andrew Harwood noted that the cans were not soldered in the usual way. The top and bottom had been heated with a resinous substance and the edges bent over so that the cover at either end could be removed to convert the can into a drinking cup. Harwood issued orders to the Potomac Flotilla to seize any vessel caught smuggling alcohol.

Sutlers were in a good position to profit from liquor sales. Regulations prohibited them from selling liquor to enlisted personnel, but many of the officially licensed merchants evaded the rules. Sutlers could openly stock whiskey because they were still allowed to sell it to officers. Brassy enlisted men frequently borrowed a pair of officers’ shoulder straps and purchased whiskey in the shops. Others stole bottles from sutler huts, wagons, or tents.

Impersonating an officer was only one of the many ways that Union and Confederate soldiers managed to get around the rules restricting their drinking. Assignment to guard duty also provided opportunities for mischief. In eastern North Carolina in April 1862, several men in the 51st Pennsylvania were ordered to guard the commissary tent in which a newly arrived shipment of whiskey barrels was stored. One night the guards took the barrels off their muskets. After unscrewing the breech plugs, each soldier had a long iron straw, which he inserted into the bung-hole of a whiskey cask and sucked himself into intoxication.

Among the busiest routes for smuggling alcohol to the Union Army was the Long Bridge, which crossed the Potomac River, linking Washington, D.C., to Virginia. On November 23, 1863, all contraband liquor seized on the bridge was turned over to the Army Medical Museum, located not far from the Washington end of the bridge. At the time, tissue specimens saved for the museum were wrapped in cloth and preserved in a keg of alcohol or whiskey. Each specimen was identified by a small wooden block, with a description written on it in pencil so that the alcohol would not dissolve the writing. Confiscated liquor was distilled again by the museum into uniform grade 70 percent alcohol, which was deemed perfect for preserving specimens.

Liquor Smuggling Gets More Sophisticated

Surgeon John H. Brinton recalled that ground around the museum was piled high with “kegs, bottles, demijohns, and cases, to say nothing of an infinite variety of tins, made so as to fit unperceived on the body, and thus permit the wearer to smuggle alcohol into camp.” Another medical officer, Acting Assistant Surgeon Ralph S.L. Walsh, marveled at the ingenuity of liquor smugglers. Goods confiscated for the museum, ranging from blackberry wine to straight alcohol, were packed in many peculiar vessels. Frequently women were arrested with belts under their skirts to which were fastened tin cans holding between a quart and a gallon of whiskey. In a number of cases the women sported false breasts, each holding a quart or more of contraband liquor. Guards seized so much alcohol at Long Bridge during the war that the Army Medical Museum had enough alcohol for its specimens until 1876.

In many camps sutlers were allowed to sell patent medicines. Often these remedies were nothing more than liquor flavored and tinted with herbal concoctions. Countless posters and newspapers touted the healing power of bitters, liquor strongly flavored with herbs. Some medicinal bitters were served as drinks in saloons. The highly advertised Drake’s Plantation Bitters, which blended herbs with St. Croix rum, was enormously popular at sutler tents.

“Snake Smuggling”?

Lieutenant Luther Tracy Townshend, the adjutant of the 16th Vermont, was also the president of the regimental temperance society. Once, in the absence of the regiment’s sutler, it fell to Townshend to order a shipment of necessities and luxuries for the troops. Some of the men persuaded Townshend to order several cases of Hostetter’s Bitters to help soldiers who were suffering from chills. The merchandise soon arrived in their camp in Louisiana. As Townshend reported, “Some of the men, who were more chilly than the others, took overdoses and in consequence became staggeringly drunk.” Only then did the mortified adjutant learn that Hostetter’s Bitters was almost pure whiskey.

An exception to the ban on sutler sales of alcohol to enlisted personnel existed in some German units of the Union Army. Brig. Gen. Louis Blenker, for one, ordered sutlers to sell beer to the soldiers of his brigade, who were predominantly German immigrants, to keep up their morale. His orders caused resentment among non-German units, although this was mollified by sutlers selling beer to soldiers outside the brigade.

Perhaps the most creative dodge was used by a soldier of the 11th Ohio, who killed a snake and, in the words of a marveling comrade, “carefully dissecting the varmint obtained a long, white cartilage, which he carefully cleaned and coiled up. Proceeding to the hospital, he politely requested a small quantity of spirits in which to preserve the curiosity (which he represented as a tape worm). The surgeon not only agreed, but complimented the man highly for the interest he manifested in natural science!”

Whiskey abuse was not confined to land-based armies. Both Union and Confederate navies faced abuses of their own. In the 18th century the British Royal Navy routinely issued a ration of spirits, usually rum, to enlisted personnel. Originally the ration was eight ounces of distilled spirits per day. Naval rum was diluted with water, resulting in the traditional drink called grog. The practice was associated with Admiral Edward Vernon, a famed officer of the mid-1700s whose service nickname was “Old Grog” because he wore a coat made of grogham cloth. (Laurence Washington, George Washington’s older brother, served with Vernon. When Laurence died, George inherited his plantation Mount Vernon, which had been named for the admiral.)

Alcohol Smuggling in the Continental Navy

The Continental Navy, as well as the early U.S. Navy, adopted the British ration of half a pint of grog per day. Before the War of 1812, imported rum from Britain’s Caribbean colonies was dropped in favor of American-made whiskey. Despite the switch, sailors and the general public continued calling the naval ration grog. On land, lower class saloons were called grog-shops or groggeries. Aboard ship, the crew’s barrels of whiskey and the officers’ private stores of liquors and wines were kept locked up in the “spirit room.” At the captain’s discretion, extra rations of spirits were doled out before and after action, or even during a battle. During the long fight with CSS Virginia, the crew of USS Monitor was braced by a special issue of two ounces of whiskey per crewman.

Captains also issued extra liquor as a reward for hard work such as the tedious and backbreaking job of loading coal aboard steam warships. Confederate sailors outfitting Sea King, which was secretly being converted at sea into CSS Shenandoah, received a serving of grog every two hours. Mariners saw the spirit ration as well-deserved compensation for their long months of hard work and isolation at sea. With some reason, temperance advocates saw it instead as a severe problem and focused considerable effort on luring sailors away from the bottle. In 1832 reformers persuaded Congress to cut the naval ration to one gill, or four ounces, daily. Sailors under the age of 21 and anyone who chose not to draw a spirit ration received instead a small cash commutation, which had risen to five cents a day by 1861.

After reducing the naval grog ration, Congress debated but did not act further on the temperance movement’s demands for tighter restrictions. A chance to end the grog ration arose again when Southern members of Congress left the nation’s capital after the beginning of the war. Northern representatives and senators were more sympathetic to the temperance cause, and with Southern seats now vacant, there were enough Northern votes to abolish the naval spirit rations. A July 14, 1862, act of Congress set August 31 of that same year as the last day for the grog ration. A correspondent aboard an unnamed vessel wrote to the Philadelphia Press that Congress had made a great mistake. He warned that ending the spirit ration would drive all the old seamen out of the service. Aboard the receiving ship North Carolina in New York City harbor, the men met the restriction with muttered growls, but no signs of incipient mutiny were readily apparent.

Kegs Auctioned Off & Turned In To Medical Staff

Spirit kegs remained under lock and key until naval vessels returned to port. About 3,000 kegs were auctioned off and others were turned over to the naval medical service for hospital use. Excess whiskey in the North Atlantic Blockading Squadron was stored aboard the aptly named ship Brandywine. As compensation for the loss of the spirit ration, the Navy added five cents per day to sailors’ pay, a raise of between 8 and 10 percent. Despite the banning of grog, there was still some alcohol aboard Union naval vessels. “Distilled spirituous liquors” were allowed on board ship as medical stores. And officers, trusted by Congress more than common sailors, were still allowed to have private stores of liquors and wines.

Grog was served in the Confederate Navy as well. Rebel tars were entitled to one gill of spirits or half a pint of wine per day. As in the Union Navy, a small cash commutation was paid to sailors not taking their spirit ration. Confederate Navy officials had considerable trouble obtaining enough spirituous liquor for rations and hospital use. Naval requirements clashed with state regulations that reserved corn and grain for food rather than distillation of spirits. Eventually a distillery was set up in Augusta, Georgia, to produce whiskey for naval use. Despite the trouble in obtaining liquor, the Confederate Navy never got around to banning its spirit ration, and it remained on the books until the war ended in 1865.

Illicit alcohol resulted in a number of embarrassing incidents at sea. Midshipman James Morris Morgan, in his memoir Recollections of a Rebel Reefer, wrote about an alcohol-fueled riot on the cruiser CSS Georgia in October 1863. Sailors slipped into a coal bunker and bored through a thin bulkhead separating the coal from the spirit room. Then they drilled a hole into the head of a barrel of liquor and inserted a lead pipe. The pilfered grog was distributed among the crew, said Morgan, “and soon there was a battle royal going on the berth deck which the master-at-arms was unable to stop.” Georgia’s first lieutenant went below and induced most of the men to give themselves up for punishment. One holdout defied the officers, but Morgan tackled him and the master-at-arms handcuffed him. Several crewmen were placed in irons and sentenced to a spell in the brig on bread and water.

Whiskey As Spoils of War

The British blockade-running schooner Sting Ray, under the command of a Captain McCloskey, was captured in the Gulf of Mexico by USS Kineo on May 22, 1864. An acting ensign with a prize crew of seven men took charge of the vessel and followed in Kineo’s wake. McCloskey produced a stash of whiskey and offered it to the prize crew. By the time Acting Ensign Paul Borner realized what had happened his men were so drunk that they were unable to get back on deck without assistance.

Borner locked the hatch to keep the men from getting any more whiskey, but McCloskey and his crew jumped Borner, took his pistol, and reclaimed the ship. Union sailor William Morgan fell overboard, and McCloskey tossed a spar into the sea as an improvised life preserver. Another man jumped into a ship’s boat, cut the painter, and escaped. The Confederates followed Kineo for a time before changing course and making a dash for shore. Seeing Sting Ray change course, Lt. Cmdr. John Watters of Kineo opened fire with a 20-pounder gun. McCloskey managed to beach the vessel after dodging several Union shells. Borner and five of his sailors were captured by the 13th Texas. Only two of Borner’s crew avoided capture and were picked up later by Kineo. Morgan, according to Watters, was “in a beastly state of intoxication, crazy drunk and howling.”

Doctors at the time incorrectly believed that alcohol was a stimulant, so they prescribed it to treat sick or wounded soldiers. Some drugs were soluble in alcohol, and patients received them in doses with whiskey or brandy. One treatment for diphtheria was a dose of brandy mixed with ammonia. Alcohol itself was seen as having curative powers for some illnesses. Laudanum, a mixture of alcohol and opium, was a widely prescribed painkiller. Ether was made by distilling alcohol and sulfuric acid, called “spirits of nitre.” A purer form of alcohol called alcohol fortius was used to make ether and to dissolve various compounds.

A Prized Commodity in Medical Treatment

Whiskey or brandy, either alone or mixed with other ingredients, were routinely used to treat patients suffering from wounds or illnesses. Usually whiskey was prescribed in frequent but small doses, perhaps one ounce or one tablespoon every few hours. Sometimes it was administered by itself, but it might also be mixed in eggnog or milk punch. One example concerned the case of Private Augustus C. Falls of the 1st New York Heavy Artillery. Falls was admitted to Douglas Hospital in Washington with diarrhea on August 5, 1864. A surgeon prescribed 11/2 ounces of whiskey each day at dinner. Three days later the dosage was raised to two ounces of whiskey three times a day. On September 29, the dosage was again increased to three ounces of whiskey every four hours. Despite the special treatment, Falls died on October 5.

One of the few effective drugs of the era, quinine, could prevent malaria or ease symptoms for patients who already had the disease. Soldiers often balked at taking their malaria medicine, though, because of its markedly bitter taste. To cajole soldiers into taking quinine, some surgeons mixed it with whiskey. This created the opposite problem; some soldiers enjoyed the quinine-whiskey dose so much that they sneaked through the line for a second prescription. While stationed at New Bern, North Carolina, the men of the 44th Massachusetts found that their medical officers took precautions to limit the soldiers to one dose each. Instead of serving quinine in whiskey, the drug came blended with medical alcohol, water, and cayenne pepper. “No soldier,” wrote a veteran of the regiment, “is known to have acquired a dangerous hankering for the mixture.”

Guilty on Charges of Drunkenness

Southern medical officers struggled to obtain sufficient quantities of medicinal alcohol. Surgeon General Samuel P. Moore established distilleries in Montgomery, Columbia, Salisbury, and Macon to produce medicinal alcohol. Volunteer committees gathered food, clothing, medicines, and creature comforts from civilians and shipped them to military hospitals. On November 22, 1861, the Charleston Mercury highlighted the first quarterly report of the city’s Ladies’ Christian Association. Among numerous shipments sent by the association to hospitals in Virginia were 34 boxes or crates of alcoholic beverages, including wine, brandy, blackberry brandy, claret, Madeira, port, whiskey, ale, bay rum, and additional alcohol in the form of medicines and bitters.

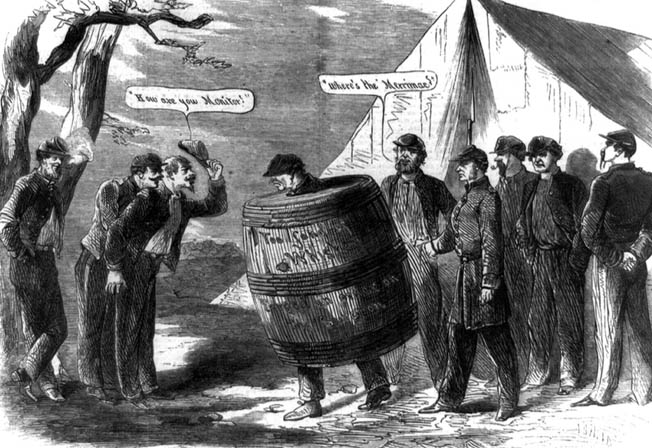

Drunkenness could be overlooked if it occurred when a soldier was off duty and did not compound his offense with other crimes. Court-martial of officers charged with drunkenness was handled differently from those of enlisted men. Officers found guilty could be cashiered with forfeiture of pay. In addition to dismissal, a Confederate law of 1862 allowed a public reprimand of officers convicted of drunkenness. An officer dismissed from the Confederate service could also be conscripted back into the ranks as an enlisted man. Enlisted personnel found guilty of drunkenness usually faced some form of confinement, corporal punishment, or public shaming. Penalties varied depending on the degree of the soldier’s offense and the policies of his commanding officer. Common punishments for drunken enlisted men included confinement in a guard tent or guardhouse, wearing a barrel with a placard noting that the culprit was a drunk, extra duty, or a spell carrying a log or marching with a knapsack filled with rocks.

Generals were not immune from abusing alcohol. Indeed, their vast responsibilities encouraged such abuse. Most notoriously, rumors of alcoholism dogged Union General Ulysses S. Grant. After Grant’s capture of Vicksburg, several gentlemen warned President Lincoln that Grant drank to excess. Lincoln was said to have asked what sort of whiskey Grant drank, because “if it makes him win victories like this Vicksburg, I will send a demijohn of the same kind to every general in the army.”

Generals Just As Guilty As Their Soldiers

A serious instance of generals drinking on duty contributed to the Union defeat at the Battle of the Crater on July 30, 1864. After successfully detonating a huge explosion in a tunnel dug under the Confederate lines outside Petersburg, Union forces moved in to exploit the break in the Rebel defenses. Brig. Gens. James H. Ledlie and Edward Ferrero remained behind the lines drinking liquor in a bombproof while their neglected divisions floundered without guidance from their commanders. The attack, which had the potential of taking Petersburg and shortening the war, bogged down, and the Union regiments were devastated by Confederate counterattacks. After investigations into their drinking and dereliction of duty, Ledlie was allowed to resign from the army, but Ferrero escaped serious penalty. He even managed to be brevetted to major general before the end of the war.

Offenses were not limited to line officers. Confederate hospital matron Phoebe Yates Pember wrote of one case in which a drunken surgeon treated a patient whose ankle had been crushed by a train. After the injuries were set and bandaged, the soldier remained in excruciating pain and his condition worsened. Checking the patient, Pember found that the bandaged leg was perfectly healthy, while the other leg was “swollen, inflamed, and purple.” The attending surgeon had been so drunk that he set the wrong leg. Fever set in and the patient died at the hospital.

Plagued with food shortages, inflation, and transportation problems, Southern soldiers and civilians dealt with severe shortages of alcohol caused by state legislatures restricting the use of grain, corn and foodstuffs for distilled liquor. Private distilling took a blow after the Federal capture of Chattanooga in September 1863 and advancing Union forces captured copper mines desperately needed by the South. Not only did their loss crimp production of brass artillery pieces, it also threatened the manufacture of percussion caps and artillery friction primers. The Confederate Ordnance Bureau confiscated scores of copper whiskey stills in western North Carolina. Metal from the stills went into many of the South’s percussion caps made during the remainder of the war.

Persimmon Brandy & Other Homemade Recipes

Southern blockade runners brought wine, whiskey, brandy and other potables from Europe. Less popular than wine and brandy, but still showing up in blockade runner holds, were rum, gin, Scotch whisky, champagne, ale, porter, and schnapps. Occasionally one might even find imported cut glass decanters to serve the imported liquors. Pure alcohol, intended as medical supplies, also passed through the blockade. Blockade-run liquor was beyond the financial means of most Confederates, forcing many people to turn to home-made substitutes. Despite wartime laws, some corn and grain found their way into whiskey. When these standard ingredients were not available, distillers turned to sweet potatoes, rice, sorghum seeds, and persimmons.

On October 21, 1863, the Charleston Courier published a recipe for persimmon brandy. Mashed by a pestle or simply with one’s hands, persimmons were mixed with warm water and left to ferment for five or six days. Then the mash was ready for distillation. In thrifty fashion, the writer suggested saving the persimmon seeds. They could be used for buttons, or parched and mixed with dried sweet potatoes to make a coffee substitute. Beer and wine were simpler to make at home than whiskey, as they needed no distilling apparatus. Newspapers published numerous recipes for persimmon beer. Wine and brandy were made from any kind of available fruit, including peaches, pears, cherries, blackberries, plums, and even watermelons.

F.P. Porcher’s 1863 work Resources of Southern Fields and Forests listed uses for hundreds of plants that grew in the Confederacy. He gave recipes for making beer from corn, persimmons, and boiled sassafras shoots. Blackberries could also be used to make wine, and with the addition of spices and whiskey, a healthy cordial could be concocted. Porcher also mentioned dozens of medicines that could be prepared from native herbs added to whiskey, wine, or brandy. Another way of coping with the lack of alcohol was to make a joke of it. By early 1864, “starvation parties” were becoming a fad in Richmond. Attendees wore the best finery they could manage. Unlike antebellum parties, there were no imported wines or liquors. The fine punchbowls and glassware remaining from the days before the war held only water from the James River.

Robert E. Lee once remarked that it was not possible to have an army without music. He might just as well have said that it was not possible to have an army without whiskey. Whether serving as an innocent aid to relaxation, medication to treat wounds or disease, or a lure to the evils of vice and desertion, whiskey and other types of alcoholic beverages were firmly rooted in the armies of the 1860s. The many creative ways alcohol found its way to soldiers and sailors, and the methods used to control its influence, are intertwined with the story of battles, generals, regiments, and ships of war.

Offenses were not limited to line officers. Confederate hospital matron Phoebe Yates Pember wrote of one case in which a drunken surgeon treated a patient whose ankle had been crushed by a train. After the injuries were set and bandaged, the soldier remained in excruciating pain and his condition worsened. Checking the patient, Pember found that the bandaged leg was perfectly healthy, while the other leg was “swollen, inflamed, and purple.” The attending surgeon had been so drunk that he set the wrong leg. Fever set in and the patient died at the hospital.

For Some, Private Distilling Filled the Gap

Plagued with food shortages, inflation, and transportation problems, Southern soldiers and civilians dealt with severe shortages of alcohol caused by state legislatures restricting the use of grain, corn and foodstuffs for distilled liquor. Private distilling took a blow after the Federal capture of Chattanooga in September 1863 and advancing Union forces captured copper mines desperately needed by the South. Not only did their loss crimp production of brass artillery pieces, it also threatened the manufacture of percussion caps and artillery friction primers. The Confederate Ordnance Bureau confiscated scores of copper whiskey stills in western North Carolina. Metal from the stills went into many of the South’s percussion caps made during the remainder of the war.

Southern blockade runners brought wine, whiskey, brandy and other potables from Europe. Less popular than wine and brandy, but still showing up in blockade runner holds, were rum, gin, Scotch whisky, champagne, ale, porter, and schnapps. Occasionally one might even find imported cut glass decanters to serve the imported liquors. Pure alcohol, intended as medical supplies, also passed through the blockade. Blockade-run liquor was beyond the financial means of most Confederates, forcing many people to turn to home-made substitutes. Despite wartime laws, some corn and grain found their way into whiskey. When these standard ingredients were not available, distillers turned to sweet potatoes, rice, sorghum seeds, and persimmons.

Dear David Norris,

Great article!! Thank you!

Is there any way I could learn the origins of a couple of quotes

you have within the article?

I am working on a children’s book.

Thank you!! Hope to hear from you!

Margie

I am researching this topic for a possible presentation; it seems that we prefer our history somewhat sanitized… You have done some good work here, and I hope to develop an interesting presentation on the role of the topic. Thank you, Mr Norris!