By William B. Allmon

In the misty early morning of February 4, 1944. thousands of Japanese troops marched silently through the jungle in the first move of their counter-offensive against the British-Indian XV Corps attempting to advance south in the Arakan region of Burma. If the counter-attack is successful, it could set up a successful invasion of India by the Japanese, who hoped to instigate a revolt of Indians against their British colonial masters. Officially called the battle of Ngakyedauk Pass, but referred to as the “Admin Box” by the British press, it foretold much of what was to come. A great deal lay in the outcome, and if the past was any predictor of the future, the Japanese would have their way.

A Bitter Defeat For Allies In Burma

Starting with the fall of Singapore, Malaya, and the capture of 130,000 British, Indian and Australian troops by the Japanese on February 15, 1942, followed by a long, painful retreat through Burma by the British led Burma Corps (Burcorps) commanded by Major General William Slim, in March and May 1942 British and Indian troops suffered one reverse after another opposing Japanese troops. During the retreat through Burma the British were outnumbered by the Japanese, untrained for jungle operations, and lacked communications and air support.

By contrast, the Japanese were trained and equipped for jungle warfare. Moving through the jungle, they would outflank British positions and cut off their lines of communication; when the British pulled back, they were cut to pieces by Japanese attacking from out of the jungle. “There was a sickening feeling that the Japanese always seemed to be one move ahead,” student of the period and author Bryan Perrett wrote, “and that they were always able to obtain local air superiority.”

By May 1942, Burcorps was thrown out of Burma, losing most of its tanks and motor vehicles, 28 out of 48 artillery pieces, and 13,463 casualties. The Japanese suffered 4,597 killed and wounded, did not pursue Burcorps into India. The monsoon season soon began, bringing British and Japanese operations, except for patrols, temporarily to an end.

A Tall Order To Build Up Indian Morale

General Sir Archibald Wavell, commander in chief of British forces in India, realized that despite many difficulties he needed to launch a limited offensive against the Japanese to build morale in India, which had deteriorated due to Japanese victories in Malaya and Burma. Wavell decided to concentrate operations in the region of Arakan in southern Burma, near India’s Bengal province.

In 1942, the Arakan was a jungle covered region on the south western Burma coast, centered on the 90-mile long Mayu Peninsula, bounded by the Naf River on the west and Mayu River on the east. A mountain range, also called Mayu, cut through the peninsula, with peaks 2,000 feet high. On the west side of the range is a small coastal strip crisscrossed by tidal creeks, swamps and rice fields, which became knee deep in water during the monsoon season.

Because there were few all-weather roads, except for a lateral one running across the peninsula, operations in the region could only be held during the dry season from October to May. “The obstacles to a campaign in Arakan are manifest,” a British general who fought in the region recalled. Despite this, Wavell decided it was the place to mount his offensive. Its immediate objective was to capture Akyab Island, to provide a fighter base for future Royal Air Force attacks against targets inside Burma.

Japanese Dug In At the Airfield Objective

Thus on September 21, 1942, the First Arakan operation began as the Indian 14th Division, commanded by Major General W.L. Lloyd, advanced south from India along the Mayu Peninsula. After a slow start the operation went smoothly. By January 1, 1943, Lloyd’s troops bad reached Foul Point on the tip of the Peninsula, and a second brigade was across the Mayu River attacking the village of Rothedaung close to Akyab Island. Determined to hold Akyab’s airfield, the Japanese reinforced their mainland positions and established a series of strong points with camouflaged bunkers. These bunkers, well dug in, with interlocking fields of fire, were impregnable to shellfire, and the Japanese could call artillery fire on attacking British and Indian troops.

Throughout January and February 1943, 14th Division made a series of frontal attacks against these positions, only to be beaten off with heavy casualties. Lloyd’s division was reinforced with fresh, untrained troops from India, until it grew to 9 brigades—which were sent into the lethal meat grinder without success.

By March 1943, despite its best efforts, the 14th Division had made no headway in its attacks on the Japanese positions. Lloyd committed the same mistakes the British had made earlier in Burma: keeping his troops on the roads, instead of sending them into the jungle, leaving them split and exposed to Japanese attacks; and wasting them in frontal attacks on Japanese positions.

Repeating Mistakes Of the Past

With the British offensive stalled, the Japanese counterattacked, falling on British lines of communication, rolling up their left flank and driving them from the coast. “In war you have to pay for your mistakes,” General Slim later wrote, “and in the Arakan the same mistakes had been made again and again until the troops lost heart. “

On May 11, 1943, Slim, now commanding the Indian XV Corps, assumed command of the Arakan Operation. For the second time in a year, he presided over a British retreat, withdrawing the 14th Division back to India for rest and refitting. For the second time, the Japanese did not follow up their victory.

Allied morale fell as the Arakan force, after losing 2,500 killed, wounded and missing, pulled back into India. “It was clear,” a British officer wrote, “that before any offensive operations could be undertaken, all arms, and particularly the infantry, needed a period of intensive training in the special tactics required to meet the Japanese in a terrain which hereto they had proved themselves supreme.”

A Change In Mindset For Jungle Warfare

Even before the start of the First Arakan Campaign, Slim had begun training his XV Corps troops based on lessons he learned during the withdraw from Burma. To defeat the Japanese, Slim believed, no attempt should be made to hold long continuous supply lines that the Japanese could cut at will. In a directive issued to XV Corps division commanders, Slim made it clear his units must become used to having Japanese in their rear, and the troops should “regard not themselves, but the Japanese, as surrounded.”

In the future, British and Indian troops cut off by Japanese attacks would not retreat, but hold their ground and be resupplied by air until relieved. Slim’s ideas were not restricted to defense; he thought the British should seize the offensive from the Japanese. “If the Japanese are allowed to hold the initiative they are formidable,” he wrote. “When we have it, they are confused and easy to kill.”

Following the Arakan campaign, XV Corps pulled back to India’s Ranchi Province, and began training for future Operations. “Training in Ranchi was continuous and active,” Slim recalled. “There were infantry battle schools, artillery training centers, cooperation courses with the RAF, experiments with tanks in the jungle, classes in marksmanship arid river crossing, and a dozen other instructional activities.”

British Test Themselves In Minor Battles

On October 15, 1943, Slim, now a full general, became commander of the 14th Army, consisting of his XV Corps, Lt. Gen. Sir Montague Stopford’s XXXIII Corps, and Lt. Gen. Sir Geoffrey Scones IV Corps. After assuming command, Slim set about overcoming the problems of health, supply and morale in his army.

As the 1943 monsoons died away, patrol activity by British, Indian, African and Gurkha troops increased along 14th Army’s front, especially in the Arakan. As his troops became better trained in jungle warfare, Slim began testing them in a series of carefully planned minor battles against advanced Japanese positions.

With the idea of giving them every advantage, Slim’s troops used battalions to attack Japanese platoons, and brigades with tanks and aircraft support to attack companies. Replying to criticism that such operations were “using a steam hammer to crack a walnut,” Slim said, “If you happen to have a steam hammer handy and you don’t mind if there’s nothing left of the walnut, it’s not a bad way to crack it.” At this stage of his army’s training, Slim believed they could not risk even small failures. “We had very few,” he wrote, “and the individual superiority built up by successful patrolling grew into a feeling of superiority within units and formations. We were then ready to undertake larger operations.”

Ready For Bigger Things

By November 1943, as a result of Slim’s efforts at improving morale and training, and the superhuman efforts by Maj. Gen. A.J.H. “ALF” Snelling, his chief of administration, to improve the lines of communication, the 14th Army was far better prepared to begin operations in Burma.

This was especially true in the Arakan, where XV Corps, under Lt. Gen. Sir Philip Christison, was preparing a limited offensive to capture the port town of Mungdaw and the only all-weather road in the area. To do so, Christison had three and a half divisions at his disposal: Maj. Gen. H.R. Briggs’s 5th Indian Division, Maj. Gen. F.W. Messeryv’s 7th Indian Division, Maj. Gen. C.E.N. Lomax’s 26th Indian Division, in reserve, and two brigades of Maj. Gen. C.G. Woolner’s 81st West African Division. Because Slim was determined that XV Corps should have armored support, Lt. Col. H.C.R. Frink’s 25th Dragoons Armored Regiment, equipped with M-3 Grant medium tanks, was also included in the offensive. In all the XV Corps had 46,000 men.

To capture their objectives, and defeat two Japanese divisions, the 54th and 55th with 28,000 men in the Arakan, Slim’s plan called for 5th Division to advance along the western half of the Mayu Range, while the 7th Division moved along its eastern side. At the same time both 81st Division brigades would move down the Kaladan Valley further to the east, threatening the Japanese right flank.

Carving Out the Jungle Supply Road

Starting on December 1, Christison began edging forward into the Arakan against light Japanese opposition. As XV Corps advanced, the difficulty in transporting supplies in a rugged, jungle-covered region became more apparent. In order to move its supplies from the west to the front, 7th Division had to use mules and porters crossing a path over Goppe Pass, then by boat on the Kalapazin River, leaving the division without motor transport or field artillery. Messervy wanted an alternative to Goppe Pass, and ordered Brigadier M.R. Roberts, commanding the division’s 114th Infantry Brigade to find one.

After a brief search, Roberts decided the Ngakyedauk Pass, a 10-mile area bounded by Taung Bazar on the north, the Mayu Range to the west, the Mungdaw-Buthidaung road to the south, and the Arakan Hills on the east, was the best alternative to Goppe Pass. The pass was already crossed by a narrow footpath, which the British had initially declared could not be converted into a road. “But a road there had to be,” Slim wrote, “and, poor as it was, this pass was the only hope in making one.” Roberts sent in the 4th Battalion/14th Punjabi Regiment of his brigade to defend the pass, while 7th Division’s engineers, using hand tools and bulldozers, began cutting a road.

By mid-December they established a jeep track, enabling medium artillery to move through the pass into the Kalapazin Valley, where the 7th Division was now facing heavy Japanese counter attacks. By Christmas, the road could carry tanks and trucks, and General Messeryv set up his headquarters east of the pass. The 7th Division established its main administration and supply point, or “Admin Box,” on the eastern side of Ngakyedauk Pass, in a mile long and 1,200 feet wide clearing, surrounded by high, jungle covered hills. In the center was a small scrub covered hill 200 yards long and 100 feet high, known as “Ammunition Hill” because of the ammunition dumps around it.

British Fight On To Break the Stalemate

Stores of gasoline, supplies and ordinance were hidden in other parts of the Box. The clearing also contained 7th Division’s transport, main dressing station (MDS); main motor maintenance section, brigade and division workshops, and ordinance field park. By the end of December 1943, the Goppe Pass route was abandoned in favor of the road over Ngakyedauk Pass. “Over this pass, christened the ‘okeydoke’ by the British soldier,” Slim recalled, “flowed the vehicles, stores and equipment needed for the 7th Division.”

The XV Corps captured Mungdaw on January 9, 1944, and both divisions met heavy Japanese resistance around the Burmese villages of Letwedet and Razabil. Brigg’s 5th Division attacked Razabil on January 26, following a heavy air bombardment by American Consolidated B-24 Liberator and RAF Vultee Vengeance bombers. British and Indian troops of the 161st and 123rd Infantry Brigades moved forward supported by tanks of the 25th Dragoons.

Despite bombing, shelling and tank support, the infantry only captured part of Razabil Village. Finally, on January 30, the attacks were called off and both brigades ordered to consolidate their positions. Christison shifted the weight of his attack to the east side of the Mayu Range by redeploying 25th Dragoons tanks, some artillery, and Brigadier Geoffrey C. Evans 9th Infantry Brigade from 5th Division, into 7th Division’s front. Christison planned to use Brigadier W.A. Crowther’s 89th Brigade from 7th Division in a wide turning movement down the Kalapazin River to break through Japanese defenses at Buthidaung, and thus end the stalemate in front of Razabil.

Battle Threatens To Expand Into a Burma Offensive

While XV Corps regrouped, patrols discovered small parties of Japanese troops northeast of Buthidaung. From mid-January, both Slim and Christison were certain that the Japanese would counter-attack. Slim recalled, “Signs were now becoming clear that this would be much more than a local affair in Arakan but rather something of the nature of a general offensive in Burma.”

Slim felt the counter attack would be an encircling movement around XV Corps’ left flank. Christison’s reinforcing 7th Division suited Slim’s idea of meeting the Japanese attack when it came, and he ordered it to continue. At the same time, Slim ordered Lomax’s 26th Division to be ready to move quickly into the Arakan to reinforce XV Corps, and Snelling to assemble supplies and aircraft to resupply XV Corps by air.

Japanese Counter-Attack Has Designs On India

While Slim prepared for what might occur, the Japanese were readying their counter stroke. In order to destroy XV Corps, the Japanese 28th Army, commanded by Lt. Gen. Shozo Sakurai, would launch an attack in the Arakan, code-named “HA-GO,” or “Operation Z.” According to the plan, Lt. Gen. Tadashi Hayana’s 55th Division would send a force under Maj. Gen. Tokutaro Sakurai to capture the village of Taung Bazar, then cross the Kalapazin River to attack 7th Division’s rear; another regiment, led by Col. S. Tanahashi, would take the eastern end of Ngakyedauk Pass and block all rescue efforts; and a force under Col. Tai Kubo would cross the Mayu Range and sever 5th Division’s supply lines. When both divisions tried to fight their way out, they would be cut to pieces. The Japanese high command hoped XV Corps would be so badly mauled it would be unable to help defend against the main offensive against India set for later in the year.

Like all Japanese plans, HA-GO depended on a strict timetable under which the destruction of XV Corps was to be accomplished in 10 days; and on the speedy capture of the supply area at Ngakyedauk Pass.

The “Admin Box” Becomes the Prime Target

At 11:00 p.m., February 3, 1944, Maj. Gen. Sakurai’s column, comprising Col. Tanahashi’s 112th Regiment, the 55th Engineer Regiment, and the 145th and 213th Battalions, set off under cover of darkness towards Taung Bazar. At 4 in the morning, February 4, sounds of marching feet and braying of pack mules was heard at 114th Brigade headquarters, where they were mistaken for RIASC (Royal Indian Army Service Corps) resupply details heading to the forward units.

After a forced march, the Japanese emerged from the jungle at nine in the morning, crossed the Kalapazin River in captured boats, and quickly overran Taung Bazar. With the village in his hands, Sakurai turned Tanahashi’s regiment south toward 7th Division’s rear, and the Admin Box. “It was now imperative for Tanahashi that the Box be taken quickly,” author William Hickey wrote. “Without British ammunition and rations, Tanahashi’s position would quickly become precarious.”

At 3:30 in the morning of February 6, the 2nd Battalion of Tanahashi’s regiment moved through the thick early morning mist towards 7th Division headquarters near the Admin Box. Slipping through the widely scattered posts defending division headquarters, the Japanese cut telephone wires, set up machine guns, and attacked.

British Defenders Pushed Back To the “Box”

“The night was alive with tracers, explosions, [and] flames from burning signals trucks,” recorded one witness, along with “the shouts of rampaging Japanese infantry [which was] like the sound of a football crowd at a cup tie.” Messeryv’s headquarters staff held the Japanese off in fierce hand-to-hand fighting.

A squadron of Grant tanks from 25th Dragoons left the Admin Box at first light to assist Messeryv’s headquarters. The tanks were delayed by mud left over from heavy rains. Then they discovered the mud made it impossible for them to maneuver on the hill slopes and they withdrew. With Japanese mortars firing into his headquarters, Messeryv ordered his staff to retreat to the Admin Box. They split into several groups, one led by Messeryv, and made their way into the jungle.

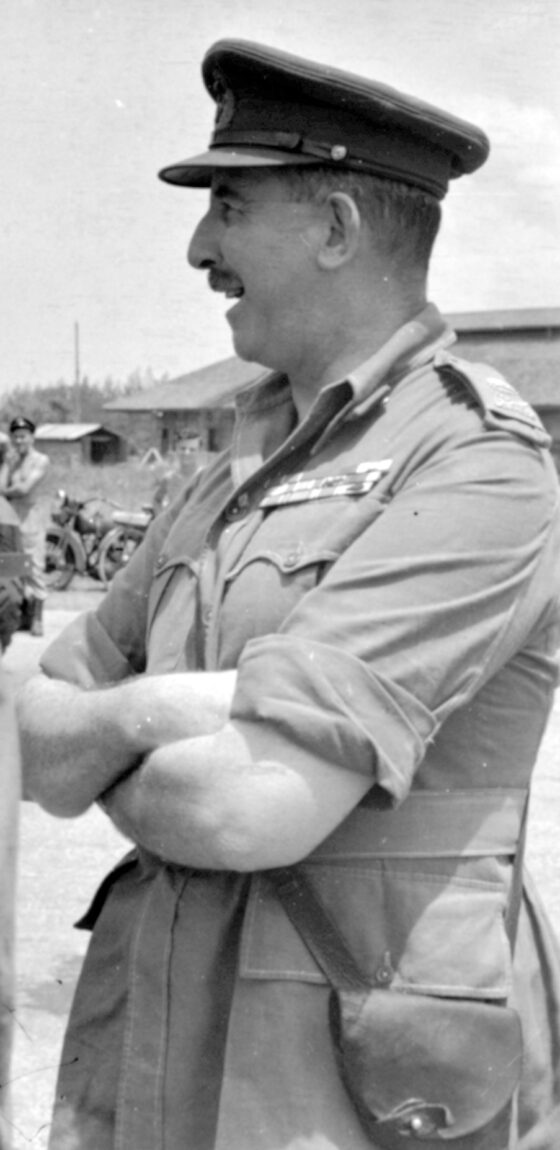

During the confusion following the attack on 7th Division’s headquarters, Christison instructed Brigadier Evans to leave his 9th Brigade with what troops he could spare, take command of the Admin Box, organize its defenses, and hold it to the last. After receiving his orders, Evans, along with A and C Companies of Lt. Col. G.H. Cree’s 2nd West Yorkshire Regiment, plus A and C Squadrons of the 25th Dragoons, headed to the Admin Box.

”Odds And Sods” Make Up Defense

When he arrived, Evans found a mixed bag of troops in the Box. He had only the two 2nd West Yorkshire companies, and tank squadrons of 25th Dragoons, along with six batteries of artillery, with 20 guns in all, as combat units. The remaining 8,000 men in the box were support troops, the “odds and sods” as they were known. “The manpower consisted very largely of Indians of the ancillary services,” Lt. Col. Cree remembered. “They were armed and had been basically trained in the use of their weapons. But the most that could be expected of them was purely static defense; they were untried in battle and untrained in anything but simply firing out of a trench.”

In order to use his infantry more effectively, Evans positioned the West Yorks’ C Company on high ground north of Ngakyedauk Pass, while A Company was placed with 25th Dragoons tanks to form a counter attack force. The “odds and sods” were assigned positions along the perimeter. “Clerks, signalers, postmen, muleteers, canteen staff, civilians, sanitation orderlies—all grabbed rifles, dug in, and prepared to fight,” one author wrote. To these troops, Evans gave one simple order: “Your job is to stay put and keep the Japanese out.”

The Ruthless First Attack

As preparations to defend the Box proceeded, General Messeryv and his group reached the Box. It was then early afternoon. Using a radio borrowed from 25th Dragoons, Messeryv established a new division command post south of Ammunition Hill, and resumed command of the 7th Division, allowing Evans to remain in command of the Admin Box garrison.

B Company of the 2nd West Yorkshire, along with two companies of the 8th Gurkha Rifles Regiment, arrived on the morning of February 7, and took up position on the eastern side of the Box. The perimeter consisted of a series of small defensive posts held mostly by administrative troops, except at the south east and south west corners where the road entered the pass; held by the Gurkhas and West Yorkshires respectively. Most of the artillery was deployed south of Ammunition Hill. The 25th Dragoons Grant tanks were held in reserve in two harbors on each side of Ammunition Hill, with A Company of the 2nd West Yorkshire, the infantry reserve, located on the hill’s west side, along with 7th Division and garrison headquarters.

The Japanese launched their first attack on the Box at dusk; attacking the eastern side first, where they were repulsed by the Gurkhas after heavy fighting. Another battalion from Tanahashi’s regiment attacked the main dressing station, guarded only by a section from the West Yorks and 20 walking wounded. Overwhelming the defenses, they murdered 40 British and Indian wounded in their stretchers, and forced the Indian Army medical officers to hand over their supply of quinine, morphine and other drugs. Then they murdered the medical officers, wrecked the hospital and dug in. A few patients and one medical officer escaped from the MDS, and reported the massacre.

“…Merely Dangerous Animals, To Be Exterminated”

At eight in the morning of the 8th, Evans sent A Company of the West Yorkshires, with a troop of Grant tanks in support, to retake the MDS. Fighting through the broken, brush covered area, the West Yorks drove the Japanese back. When A Company finished clearing the hospital area on February 9, they found only three survivors of the casualties who’d been in the hospital when it was overrun. These men were transferred to a new dressing station inside the perimeter.

The barbaric massacre at the MDS proved counter-productive to the Japanese. “British and Indian troops retained few illusions about their opponents, but they had respected them as soldiers,” author Bryan Perrett wrote. “Now they saw them as merely dangerous animals, to be exterminated with every means at their disposal.”

Major Air Resupply Mission Launched

Having been cut off from their supply routes on February 7, and being ordered to stand fast, the air supply operation was ordered. Beginning on the 8th , Douglas C-47 Dakota transports of RAF Troop Carrier Command took off from their airfields in India to resupply XV Corps by air. It was just the beginning. Over the next five weeks, despite Japanese fighters, small arms and anti aircraft fire, Troop Carrier Command flew 714 sorties, delivering 2,300 tons of supplies to the 7th and 81st Divisions; 5th Division received the bulk of its supplies through the port of Mungdaw.

While air supply to the Box went on, Japanese attacks continued. At dawn on February 9, Japanese mountain guns on Hill 315 near the eastern side of the Box fired on Ammunition Hill, setting the ammunition stored their on fire. In response, Evans sent the West Yorks B Company, led by Major A.C. Dunlop, with a troop of Grants to counter attack, while working parties brought the fires under control. B Company stormed the hill under supporting fire from the tanks, driving the Japanese off.

Captured Map Reveals the Japanese Were Far Behind Schedule

After clearing the hill, the West Yorks found the body of a Japanese officer; on him was a map containing detailed plans of the HA-GO offensive. “Thanks to the Japanese habit of carrying orders and marked maps into action, we had an almost complete picture of their general plan,” Slim said later. The captured map showed the Japanese were far behind schedule; they had not captured any guns or supplies, and the British had not panicked or retreated as expected.

Inside the Box, life gradually settled into a daily routine. “At dusk we all stood-to for an hour, sometimes two; then followed the long night of double sentries, continual watchfulness and the expectation of a full scale attack,” Col. Cree recalled. “No night ever passed without an affair of some sort on some part of the perimeter.”

Because of British superiority in artillery and tanks, the Japanese attacked mostly at night. Infantry encounters along the perimeter were hard fought, at close quarters with bayonets and small arms fire. Often the Japanese would attempt to unnerve the defenders by shouting orders or screaming for help in English or Urdu. “This created tension, but the technique was now familiar and the enemy’s difficulty with the letter ‘L,’ which he pronounced as ‘R,’ was a certain giveaway,” Bryan Perrett wrote.

Both Sides Use Artillery To Full Advantage

During the day, the Japanese made good use of their mortars, a few 105-mm howitzers, and a few Model 92 70-mm mountain guns, in shelling the crowded perimeter. British guns inside the perimeter returned the Japanese fire. The 8th (Belfast) Heavy AA-Regiment’s four high velocity 3.7-inch guns were highly effective against Japanese fighter-bombers, and lethal against targets in the surrounding hills. A battery of 5.5-inch howitzers of the 6th Medium Artillery fired at targets 400 yards from their positions. When asked by radio their situation, they replied, “Fine, but drop us a hundred bayonets.”

Under continuous harassing fire by day, and infantry attacks by night, life inside the Box was difficult. “The dust, the foul water and the abominable, eternal stench are memories which will long linger,” Col. Cree recalled. “Comfort, sleep, and even rest were foreign to us.”

After the first days of the siege, the troops inside the Box realized that, having been forced into a stand-up fight, the Japanese soldiers of the 55th Division were poor battle practitioners. Their attacks were poorly coordinated and covered ground where attacks had failed before. Due to their lack of coordination, Evans was able to commit his reserves where there were needed, and could defeat any lodgment by point blank fire of 25th Dragoons’ tanks. Although obsolete in the European theater, the Grant was highly effective in jungle fighting; its sponson-mounted 75-mm gun fired high explosive rounds, while its turret-mounted 37-mm gun flayed the jungle with man killing canister rounds. Tanahashi’s men did not have tanks or anti-tank guns to counter 25th Dragoons’ Grants, and their artillery, although effectively used, could not match Evans’s artillery support.

“Typical Dull Japanese Ferocity”

By February 14, HA-GO was fatally behind schedule. By now, Tanahashi’s men were living off unhulled rice and roots, having consumed the last of their rations. Hayana’s division was coming under increasing pressure from the 26th Division attacking from the north and Brigadier T.J. Winterton’s 123rd Brigade from Briggs’s 5th Division attacking from the west. But Hayana, with what Slim called “typical dull Japanese ferocity,” continued attacking the Admin Box instead of bypassing it and gambling on capturing supplies elsewhere.

Under pressure from Hayana to overcome the Box, Tanahashi on the evening of February 14 launched an all-out attack with all three battalions of his regiment. “The night throbbed with screams, rifle fire, and shell fire,” Louis Allen wrote. But “Tanahashi could wrest no decisive victory in the face of determined resistance.” At one point, a Japanese tank destruction party tried to reach the 25th Dragoons’ tank harbor east of Ammunition Hill across open paddies. They were met by a hail of machine gun fire and were all wiped out. “The night was brilliant with star shells,” an eyewitness wrote, “and the tanks poured machine gun fire into the Japanese until their casualties forced them back.”

Retaking the Hill At All Costs

While Tanahashi’s attacks were being repulsed, another column made its way to a height overlooking the western side of the Box, known as “C Company Hill” by the British. It was defended by a single platoon from C Company of the West Yorks. Early on the morning of February 15, the Japanese attacked, sweeping the defenders from the crest. Evans, knowing the Japanese on C Company Hill were only 300 yards from his headquarters, overlooking the hospital’s new position—and remembering the events of February 7—ordered the hill retaken.

At daylight A Company of the West Yorks, led by a Major O’Hara, along with 10 Grants of 25th Dragoons’ A Squadron, counter attacked. The tanks fired high explosive 75-mm shells at the summit, keeping the Japanese pinned down, while Major O’Hara’s men moved up the slope.

A Company’s first attack was met with a shower of Japanese grenades; O’Hara pulled back to let the tanks resume shelling the crest. Then A Company moved back up the ridge again, following the curtain of shells and machine gun fire. When the tanks ceased fire, the West Yorks charged the Japanese positions, clearing them from the crest, killing 17 in the process. C Company Hill was back in British hands.

Point, Counter Point At the “Box”

During the night of February 15, as arranged by Evans days before, Brigadier Crowther moved his 89th Brigade headquarters, along with a battalion of the 2nd King’s Own Scottish Borderers (KOSB) into the Box, and took over the eastern half of the perimeter from the 2nd West Yorkshire. Because of casualties and sickness, both A and B Companies of the West Yorks were down to half strength, with only 100 men each, when the KOSB took over. For the Box’s defenders, the next few days, from February 16 to 21, were spent patrolling and clearing isolated Japanese pockets around the perimeter.

Meanwhile, outside the Box, Hayana’s men were being pressed in an anvil formed by the 7th Division and both Lomax’s 26th Division, and Maj. Gen. F.W. Festing’s 36th Division descending from the north to reinforce XV Corps. In addition, Briggs’s 5th Division’s 123rd Brigade continued fighting their way up Ngakyedauk Pass. Brigadier Winterton’s advance, led by the 2nd Battalion/lst Punjab and 4th Battalion/7th Rajput Regiments, was stalled on February 20 by a Japanese bunker complex on a hill known as Point 1070. The next day, February 21, a 5.5-inch howitzer was brought up to the pass and fired twenty rounds into the bunkers. Japanese resistance on Point 1070 collapsed; the advance resumed, only to be delayed by another roadblock.

The Japanese Launch Desperate Suicide Attacks

While Winterton’s men fought their way towards the Box from the west, Messervy dispatched the Dragoons’ C Squadron and two companies from the KOSB from the Box with orders to head east for a link up with the relief column. During the night of February 21, Japanese troops all along the Admin Box perimeter launched suicide attacks. “It was clear from these desperate measures that the enemy commanders were facing a crisis,” the British official history reported. All of the attacks failed, and the Japanese were driven back into the jungle.

C Squadron and the Borderers resumed their advance up the road on February 22. At the same time, 123rd Brigade attacked the Japanese positions from the west. After a short, sharp fight, the Borderers met the lead company of 4/7th Rajputs. Thus the siege of 25 days was broken.

That night, Col. Tanahashi, his efforts to penetrate the Box’s defenses having failed; with ammunition gone and food scarce, decided he had no choice but to break off his efforts. Ignoring Hayana’s orders to attack the Box, Tanahashi began pulling his men back to their original starting line. “I regret this, but am determined to do it,” he radioed Hayana on February 24. “There is no alternative.” Out of 2,190 men in his 112th Regiment when the operation began, 400 survived the siege.

The Final Retreat

After consulting with General Sakurai at 28th Army headquarters, on February 25 Hayana finally bowed to the inevitable and ended Operation HA-GO. He had lost 5,000 men dead around the Admin Box, Ngakyedauk Pass and along the Mayu Range. Barely 3,000 out of the 8,000 Japanese troops participating in HA-GO returned to their original positions.

In contrast, Christison suffered only 3,506 casualties, half in the 7th Division and corps troops under its command. Despite this, Christison resumed this offensive against Razabil

and Buthidaung by the first week in March, giving the Japanese no respite. By May 3, XV Corps had captured both Razabil and Buthidaung. “Revenge is sweet,” Slim recalled years later. “The XV Corps had now achieved all the tasks I had set it.”

Victory Became a Turning Point

The battle of the Admin Box, fought in a remote, relatively unimportant area of Burma, was a great tactical victory for Slim, and the 14th Army’s first victory over the Japanese, marking a turning point in the war in Southeast Asia. “It was the first time that the Japanese met trained British/Indian formations in battle,” reported the official British history, “and the first time that their enveloping tactics, aimed at cutting their opponents’ line of communication, failed to produce the results they expected.”

Slim’s ideas on how to defeat the Japanese, and his training methods were proven correct. And the victory had a great effect on British morale. “An assortment of butchers, bakers, clerks, drivers, muleteers and sanitary orderlies had handed out a fair beating to some of the best infantry in the Japanese army and walked taller because of it,” Bryan Perrett wrote. It demonstrated that the Japanese were not supermen, and that British and Indian troops could fight and defeat them in the jungle. “It had been imperative that this first big battle fought by 14th Army be a success,” Geoffrey Evans said later, “and Slim, his officers and their men had won it.”

Years later, summing up the campaign in his memoirs, Defeat into Victory, Slim wrote: “This Arakan battle, judged by the size of the forces engaged, was not of great magnitude, but it was, nevertheless, one of the historic successes of British arms…. It was a victory, a victory about which there could be no argument, and its effect not only on the troops engaged but on the whole Fourteenth Army, was immense.”

A wonderful summary above

I am writing a short article on David Arthur Sydney Day a Captain in the Wiltshire Regiment, 1st Battalion who was killed on 24/2/44

Are you able to detail the involvement of Day’s Battalion ? Would you have any details of Day’s death ?

Many thanks

Peter r

A great article on a battle that tends to be forgotten, just as easily as several of the campaigns of SE Asia.

Sir, would you have some information on the performance of the Indian Army Ordnance Corps in the Battle of the Admin Box?

As Messervy was in the jungle and out of contact, Christison, the Corps commander, ordered Brigadier Geoffrey Evans, who had recently been appointed commander of 9th Indian Infantry Brigade, part of the 5th Indian Division, to make his way to the Admin box, assume command and hold the Box against all attacks. [9] Evans reinforced the defenders of the box with 2nd Battalion, the West Yorkshire Regiment from his own brigade, and 24 Mountain Artillery Regiment IA.