By John Wukovits

Staff Sergeant William Nolan dared not raise his hopes this August day in 1945, but something unusual was unfolding. Japanese guards normally escorted him and the other prisoners from their Kosaka, Japan, prison camp to the copper factory. Today, though, they were ordered to remain in their barracks. “Usually we tramped to work every day, except for the emperor’s birthday,” recalled Nolan. “Rumors of the war’s end had bounded through camp for the past week. Later that day, around noon, we heard the war was over.”

For Nolan, an excruciating three-and-a-half-year ordeal neared its end. From April 1942, when he put down his weapons in the Philippines, until August 1945, Nolan endured a seemingly endless stream of prison camps, cruel guards, and hell ships that so ravaged his body that his weight plunged from the 170s to fewer than 100 pounds. His agonizing odyssey started with a march that has entered the annals of war as one of the most infamous deeds ever recorded, a walk more commonly known by its horrifying title—the Bataan Death March.

A native of Michigan, William Nolan started his military service on March 7, 1941. He arrived in Manila the following September, where he worked in communications for the 515th Coastal Artillery out of nearby Fort Stotsenburg. Duty in the Philippines offered a luxuriant alternative to the rigid lifestyle offered by most military posts.

“We had an easy life out there, with frequent parties and dances. Talk about preparedness for war—those men in the Philippines were no more an organized Army than the man on the moon.”

The situation dramatically changed on December 8, 1941 (December 7 at Pearl Harbor), with the surprising news that Japanese aircraft had dealt a stunning blow to the U.S. Pacific Fleet in Hawaii. “I had just returned to my barracks from church when I heard on [the] radio that Pearl Harbor had been bombed,” remembered Nolan. “We were shocked. We didn’t know much about Pearl Harbor other than it was a huge Navy base.”

Devastating Accuracy From the Japanese

Around noon on December 8, Japanese fighters and bombers destroyed most of General Douglas MacArthur’s Philippine air force on the ground when they swept down on airfields near Manila. Their accuracy shocked Nolan, who recalled enemy fighter pilots strafing each road as though they “had a map of the Clark Field area in their minds.” Nolan accompanied half of his unit to Manila, where he spent the night “cleaning guns of oil and cosmoline so they would be ready to use.” The next day he headed to Nichols Field to wire the area for communications.

Nolan claimed morale remained high in the early stages. “We felt, what the hell, we have enough equipment to hold them off,” until reinforcements arrived. “The food was not so bad at this time. We had a choice of three old World War I C-rations, pork and beans, spaghetti and meatballs, and stew. It wasn’t that bad, I guess, mainly because we didn’t have anything else to eat.”

For the next two weeks Nolan remained near Manila, loading trucks with guns and ammunition for the withdrawal to the Bataan Peninsula. “Before December 25, we got hit every day by Japanese bombers, usually about the same time in the morning and afternoon. We had no desperate feeling yet, and we thought that help was coming. In fact, I once went into Manila and sent a Western Union telegram home saying everything was fine, then strolled through a huge department store looking at all the products.”

When a large enemy force rushed ashore at Lingayen Gulf to the northwest and Lamon Bay to the southeast on December 22-23, Nolan’s unit pulled back. After enjoying a Christmas feast of turkey and trimmings, his last decent meal for almost four years, Nolan drove an equipment-laden truck to prepared defensive positions near the small town of Pilar along Bataan’s east side. It was here that Nolan first realized the predicament he and his comrades were in.

“We had 1918 equipment that just wouldn’t work and old Springfield rifles with one shot, one bolt action.” An officer on the staff of General Jonathan M. Wainwright, the commander who succeeded MacArthur when the latter was ordered out of the Philippines by President Franklin D. Roosevelt, wrote in a memo at the time that only 20 percent of the mortar rounds and 10 percent of the hand grenades exploded. Inexperienced fighter pilots soared aloft with faulty ammunition that frequently jammed or failed.

“Japanese Planes Flew at 20,000 Feet, but Our 3-inch Guns Only Fired up to 18,000 Feet.”

“Pilots couldn’t fly some of the fighters that came out to the Philippines because someone in the States decided that since the planes were headed for the tropics, they didn’t need antifreeze!” exclaimed Nolan, still incredulous after five decades. “Japanese planes flew at 20,000 feet, but our 3-inch guns only fired up to 18,000 feet. We could see the shells exploding short of the targets. Anyway, half the time the shells wouldn’t explode. That was demoralizing. We were firing back but doing nothing.”

Dwindling food and medical supplies plagued the weary troops. Known as a breeding ground for malaria, Bataan sapped the strength of the American units, especially as quinine to combat the illness ran low. At any one time, Nolan claimed that half his outfit of 250 men suffered from either malaria or dysentery. “Guys were running into bushes to defecate, or either freezing or sweating to death from malaria. You couldn’t get much sleep, but you did your job because you had to.”

As conditions worsened, soldiers gradually pinned their hopes on the anticipated reinforcement convoy which, rumor stated, was already steaming across the Pacific toward Bataan. While one soldier explained that everyone held on to rumors because they “gave us something to believe in. When morale is so bad and there’s nothing more to do, rumors help,” Nolan remained dubious. American strategy called for holding Bataan as long as possible until reinforcements arrived, but Nolan surmised that “with our supplies getting lower and with all the civilian refugees flooding in, we had no hope of that.”

Insufficient supplies and deteriorating health increasingly weakened the beleaguered troops as they struggled through January and into February 1942. A scant 27.7 ounces of food per day, less than half the normal peacetime ration, was available for each defender. By early March that amount dipped to under 15 ounces.

Destroy Your Weapons and Wait for the Enemy…

“We were down to some rice and salmon, plus anything you could shoot and skin,” recalled Nolan. “It was right about this time I began thinking our situation was hopeless, although a lot of the guys wouldn’t admit it and kept hoping for the convoy. I couldn’t buy it. We were thousands of miles from the States, on a peninsula being attacked on land by Japanese units and surrounded at sea by the Japanese Navy. Morale started to get lower and lower as soldiers got weaker and weaker. We had no cover from mosquitoes at night because we slept at our positions, and guys were so sick they couldn’t do a hell of a lot.”

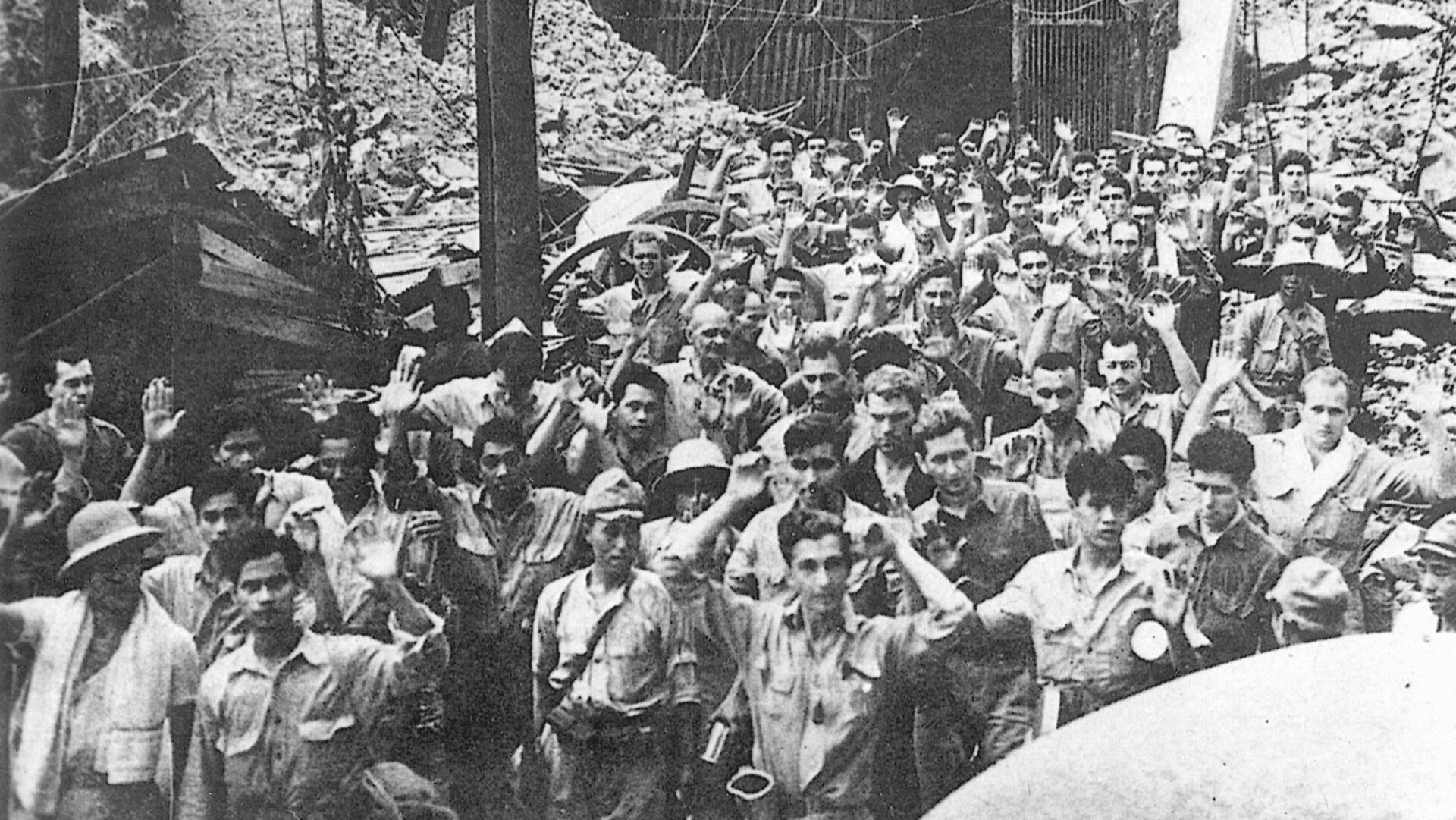

The end came on April 9, when 12,000 Americans and 63,000 Filipino soldiers lay down their arms on orders from Maj. Gen. Edward P. King, Jr. An officer from King’s command drove up to Nolan’s 37mm gun at Cabcaben and told the men to destroy their weapons, then sit and wait for the enemy to arrive.

“By now the Japanese, many with branches tied to them so they looked like bushes, had advanced to within 500 yards of us. They had pushed us back far, and we didn’t have much left, either in ammunition or strength. Some of the men blamed MacArthur for our predicament and bitched that he left for Australia, but most of us knew he’d been ordered out. I thought he did a hell of a job holding up the Japanese as long as he did.

“Actually, the surrender came as kind of a relief. We’d no longer have to fight, and we thought we’d be treated halfway decent, maybe even swapped for Japanese diplomats. There was a feeling of, ‘Oh boy, this is over!’ Little did we know how much worse it was going to get.”

Hastily drawn Japanese plans for prisoner evacuation and even speedier implementation led to chaos and brutality for Nolan and the other men about to surrender. Since Imperial Japanese Headquarters wanted the nearby island of Corregidor seized immediately after Bataan fell, Japanese commander Lt. Gen. Masaharu Homma ordered the prisoners quickly removed from Bataan to make room for Japanese soldiers. His transportation officer, Maj. Gen. Yoshikata Kawane, organized a two-phase withdrawal. First gathered at Balanga after a march of up to 19 miles, the prisoners would be transported 36 miles by truck and train to Camp O’Donnell. Food would be distributed at four stops along the way, and every mile rest stations containing water and sanitary facilities would supplement two hospitals situated along the route.

These plans rested upon inaccurate assumptions. First, Kawane worked with inadequate supplies since the Philippines operation had taken a back seat to Japanese advances in Malaya and the Netherlands East Indies. Kawane had no inkling that the prisoners would be as starved and weak as they turned out to be, and he planned for no more than 25,000 to 35,000 captives. He also believed that he would have at least a month to implement these measures before Bataan crumbled. Instead, Bataan collapsed within one week.

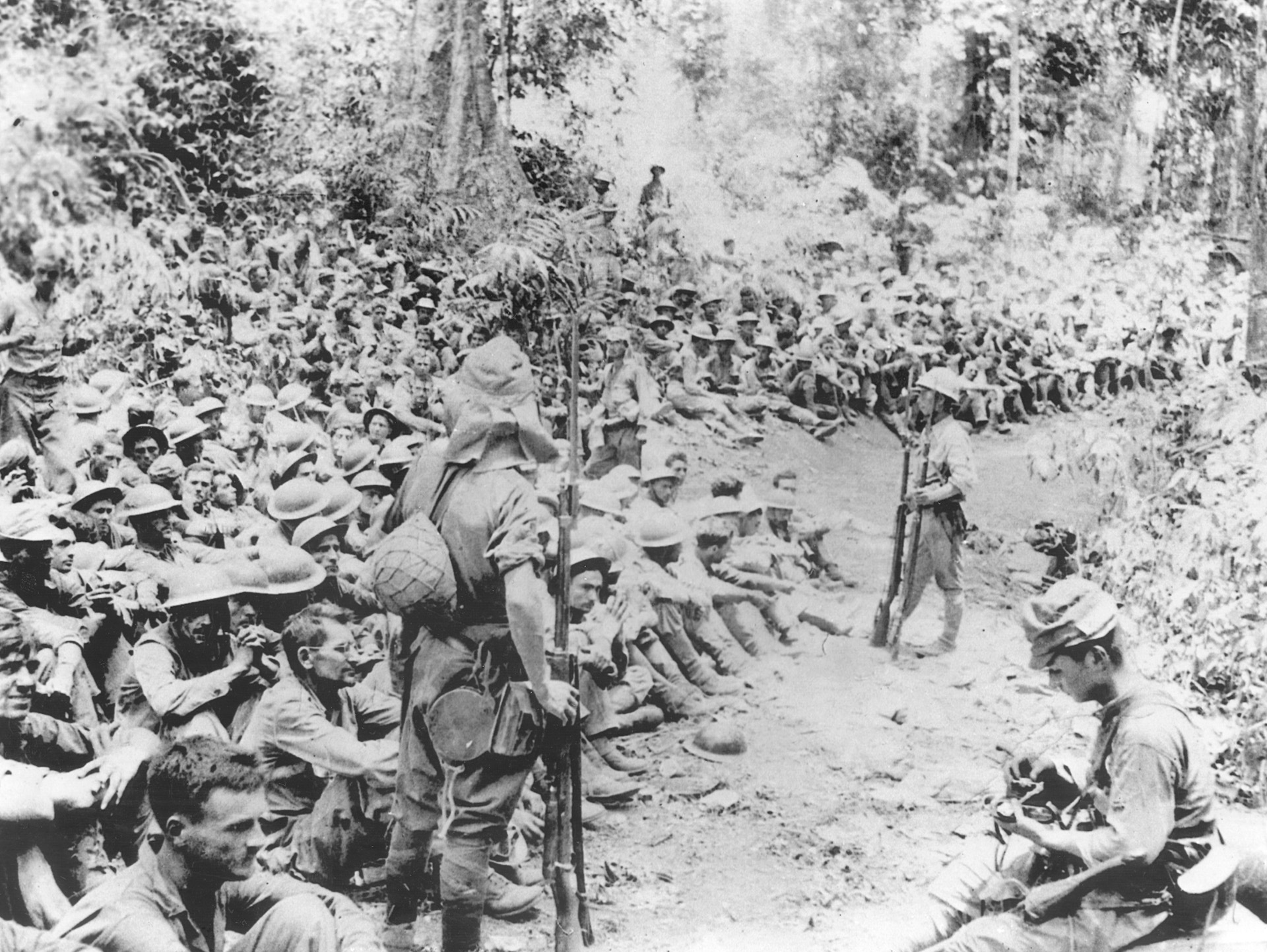

What was to be an organized movement of prisoners rapidly dissolved into the notorious Death March. The Japanese first searched each prisoner, then put them into groups for the trek. As the silent line of ragged fighters trudged along Bataan’s coastal route, Japanese soldiers heading for the front walked or rode in trucks past their defeated foes, often asking the location of a supposed tunnel between Bataan and Corregidor, or the positions of huge American guns.

The Start of a Grueling Ordeal for the Prisoners

“My first realization this was going to be a tough ordeal came that initial day, when they refused to let us rest. Those guards were just young privates who didn’t know what the hell they were doing,” remembered Nolan. “Some American officers tried to organize us and get us some food, but they were either beaten or killed, so we shut up. The word passed down the line to get rid of Japanese money or souvenirs, because that meant instant death if they found any on you.”

Groups of as many as 300 prisoners started leaving Mariveles on Bataan’s southern edge on April 10. As he inched north, Nolan learned to look out for passing Japanese trucks since their occupants often reached out and tried to smack American prisoners with their rifles. He marched all day on a dusty road without food or water in searing 95-degree heat and saw fellow sufferers dash from the line toward nearby water, only to be shot dead within a few paces.

“I couldn’t conceive this stuff happening. I had the urge to kill the guards, but what could we do? The first guy I saw killed—that didn’t set well with me. It was terrible to keep walking when you were barely able to lift your feet above a shuffle. Those who fell on the side of the road were either bayoneted, shot, or trucks ran over them. I kept going by focusing on what I was doing and not thinking about the atrocities. More men died each day, but they gradually became simply more men dead—I was alive and concentrated on that.”

Most soldiers reached their first stop, Balanga, Bataan Province’s capital city of 5,000 people, within two to three days. A little rest, water, and a small portion of rice and salt somewhat alleviated the misery, but most men were not permitted to pause for long, nor was there enough food for every captive.

Intolerable Suffering or Death Were the Only Options

Three other stops dotted the march but hardly eased the prisoners’ discomfort. A rice paddy enclosed by barbed wire housed the men at Orani, 11 miles from Balanga. As each group passed through, the field became so progressively foul with human waste and dead bodies that an overwhelming stench assaulted the marchers before they entered the town. At Lubao, a city of 30,000 inhabitants 16 miles farther along the trail, prisoners stumbled into a sweltering tin building that contained only one water spigot for all the men. San Fernando, an important rail center nine miles from Lubao, was the last resting place. After plodding along an asphalt road warmed by the sun and churned into sharp chunks by passing trucks and tanks, various groups of prisoners filtered through San Fernando for two weeks on their way to waiting boxcars for shipment to prison camp.

“It took us nine days to get from Cabcaben to San Fernando, and I can only remember getting rice and water once before San Fernando,” said Nolan. “I weighed 170 pounds when I got to the Philippines, 150 pounds at the surrender, and a lot less when I got to San Fernando. We would collapse to the ground at each stop we were so exhausted, and at San Fernando I fainted while standing in a food line. Some guys went crazy and started for the fence that enclosed us, but they always got shot.”

Through it all, movement became essential—take one step, then the next, then another. No matter how hot, how tired, how scared a prisoner became, he had to keep going; to fall behind was to die by bayonet or gunshot. “It happened often, and we were not allowed to pick them up. The bodies of some men who had fallen were flattened into the road by speeding vehicles,” Nolan said. One unfortunate soldier disappeared into the dust after 10 Japanese tanks rolled over his fallen body, leaving only small signs of a tattered uniform pressed into the ground.

Infuriating Helplessness

“I got mad when I saw all this,” added Nolan, “but there wasn’t a damn thing I could do. Mostly you just became numb to it all and kept telling yourself not to fall or you’d be dead.”

Thus, the struggle centered on sick, weakened men laboring in withering heat to remain on their feet. Hot when the prisoners started each morning, the unforgiving sun intensified through the day, transforming the road into a suffocating, dust-covered gauntlet of misery.

“The roads were so dusty we looked like we had pancake on. Malaria and dysentery further messed the road. We plowed along, like cattle, and played mental tricks with ourselves by thinking that something better waited for us just up the road,” remembered Nolan. “Every once in a while, if the guards weren’t looking and there was some water by the road, we’d try to quickly scoop some up, even though we could see dead Americans and animal carcasses lying in it.”

Nolan’s mechanical pencil almost landed him a full bucket of water. A Japanese soldier found it on Nolan at the march’s start, but let Nolan keep it because “the lead portion was inside the pencil, so he couldn’t write with it. The guard thought it was useless. During the march we were stopped near an artesian well, but the guards wouldn’t let any of us get to it. I took out the pencil, turned it so the lead was out, and handed it to the guard. He let me get a bucket of water, but as I was walking back to the line with it, the same guard kicked it over. I saved only enough to give a mouthful to a few men near me.”

Dead Prisoners: as Common as Roadkill

As the weary, ragged line of prisoners meandered up the peninsula, it became more common to see American and Filipino bodies, many beheaded, lying in ditches alongside the road. One officer counted 27 headless bodies before forcing himself to think about something else. From then on he walked with his eyes fixed straight ahead.

“It was routine to see bodies lying along the side,” mentioned Nolan. “You gradually just don’t pay any attention to them. They were dead, so there was nothing you could do anyway.”

Instead, survivors focused on the living. Nolan stayed with the same handful of men, each of whom tried to help the others. In many larger groups, the weakest men were often placed near the front of the line each morning so that as they became more exhausted the men behind would grab them by the arms to help prop them up. As the day moved along, the weary soldiers were slowly passed down the line until, hopefully, a rest stop arrived.

One is struck with how often survivors of either the Death March or a prison camp credit hatred or some other potent emotion with keeping them alive. Strong emotions rouse the spirit and give purpose to life, while those who permitted emotions to slip away often succumbed.

“I stayed alive because I kept telling myself I would make it, that I could take anything the Japanese could give me,” explained Nolan. “I was an independent guy and could take care of myself, but it seemed the oldtimers and the real young ones had the most trouble. We had guys 18-19 years old who said they couldn’t live like this and lay down to die. You couldn’t do anything to change their mind, either. It was already made up. We used to say over there that the good guys died and the sons-of-bitches lived because they would fight to live.”

A gruesome 25-mile train ride from San Fernando to Capas, followed by an eight-mile march into temporary quarters at Camp O’Donnell were the next ordeal for Nolan. Metal boxcars seven feet high, 33 feet long, and eight feet wide, built to carry no more than 40 people, waited to transport the prisoners. Japanese guards brutally wedged more than a hundred weary marchers into each stifling container for the four-hour ride.

Intentional Malnourishment Prevented Escape

Nolan compared his boxcar to an oven made even hotter by a blistering midday sun. “We had to stand up because there was no space to sit down. I was fortunate to be located near one side, so I got some air from outside through small crevices in the wall, but other guys had to fight for air.” Fecal matter and vomit from dysentery sloshed about the floor as the train bounced on the rails. “Guys were so weak and sick that they didn’t care anymore” and perished in the oppressive heat of the boxcars.

From Capas, the men laboriously walked to the unfinished barbed-wire-enclosed Camp O’Donnell, where Nolan began his years of confinement. The horrid Death March, during which as many as 650 Americans perished, was over for Nolan, but a series of tribulations awaited.

Nolan’s unpleasant introduction to prison camp life set the tone for his next three and a half years. The camp commandant, Captain Tsuneyoshi, made the exhausted men stand in the blazing sun while he harangued them on how they were to behave. He added that the men would purposely be given little food to prevent their gaining enough strength to escape.

Nolan remained in O’Donnell until early June, when he was transferred to the camp at Cabanatuan, 100 miles north of Manila. The weakened Nolan, whose weight had slipped from the 170s to 105 pounds, looked so ghastly that the Japanese assumed he would soon die. “The Japanese wanted to put me in what we called the Zero Ward. That was where they put serious dysentery patients, and we believed that once you went in there you never got out alive. I refused to go, then started stealing any food I could find and slowly started regaining some weight.”

Cabanatuan proved to be a bit better than O’Donnell, as American officers had an opportunity to implement some organization and activities. Most men either worked on a farm or built roads. Few attempted to escape.

Nolan recalled, “We were on an island in the Philippines, with the Japanese Navy all around us, and living among natives with darker skin. But the biggest thing was the Japanese put us into groups of 10 and warned us that if any one of the 10 tried to escape, the other nine would be shot. We decided it would be up to each man if he wanted to try it, but that he had to let the other nine know about it ahead of time so they could go with him.”

Some men doubted the Japanese would actually kill nine men to prevent one escape, but they soon learned otherwise. “There was a set of twins who lined up next to each other when the Japanese were putting us into groups of 10. In the counting off, the first twin ended up being number ten of one group, while his brother became number one of the next group. One guy escaped from the first twin’s group and, while the second twin watched in horror, his brother was lined up with the other eight prisoners and shot to death,” commented Nolan.

In early 1943, the Japanese again moved Nolan, this time to a camp in Lipa, 60 miles south of Manila. The food slightly improved, although the rice they received was usually heavily populated with bugs. Occasional servings of meat and pieces of coconut helped supplement the meager diet.

Kind Guards Were an Extreme Minority

Since the Japanese viewed surrender as abject humiliation, they had few qualms about mistreating the prisoners. Nolan and the others had to bow whenever they passed a Japanese soldier, “and it wouldn’t take much for us to get beat. Once I was beat with a rifle and boots. But you know, if a Japanese officer was not happy with a Japanese soldier’s job, he’d beat the Japanese soldier, too.

“We used to give each guard a nickname, like Porky Pig or Mickey Mouse. They thought it was great, until one day they went into town and saw a cartoon with those figures. They came back to camp and beat us.”

Although it was difficult to think anything but harsh thoughts about their captors, Nolan remembered a few guards who treated the men decently. One Japanese soldier snuck food into camp and handed it to the prisoners. Unfortunately, Japanese like him stood in a small minority.

The prisoners worked 12-hour days building airfield runways. In little ways, the Americans did what they could to impede the Japanese war effort. “I remember one time when we purposely made the cement for the runway too thin,” related Nolan. “Later in the year, when the big rains came, half the runway washed away because there wasn’t enough cement. That was our way of getting back at them. They never retaliated, so I’m not sure they ever figured it out.”

Each man handled the strain differently. Some simply gave up and died, while others focused on an intense hatred of the Japanese. Nolan placed all his energies on making it through each day. “I tried not to think about the future. I just tried to go day to day and figured I could take whatever the Japanese had to give me. I didn’t get too upset with the idea that I might die. If you’ve enjoyed life, why worry about death, and over there I saw so much death that it became the norm.

“Some guys had trouble eating the food, but I was willing to eat anything to survive. We had a group of prisoners who were Native Americans from New Mexico, and they used to show us what was safe to eat from the land. They were accustomed to living in harsh terrain, so they’d point out things like pepper plants, tree blossoms, and a weed they called pig weed that pigs in New Mexico used to eat. We figured if it was all right for pigs, it was safe for us. Some prisoners, though, wouldn’t touch the stuff. One 18-year-old said he couldn’t live like this and that he couldn’t eat the rice—he called it slop. Well, you either ate the slop or you died, so he died.

”If God Wanted to Take Me, He’d Take Me, So Why Worry About Dying”

“Fortunately, I could take care of myself, but others could not. That young kid who refused to eat, he was a farm kid, was homesick for his mom, and instead of battling to stay alive he gave up. He just sat down and that was it. The whole thing was too much for him, and you couldn’t change his mind.”

Besides a gritty determination to survive in situations that caused others to die, Nolan relied on thoughts of home and religion to help sustain him. “Religion was very important to me. I learned that if God wanted to take me, He’d take me, so why worry about dying. At Lipa we had a Catholic priest from Notre Dame who had been a good friend of Knute Rockne [legendary football coach]. He used to tell us incredible stories about Rockne. Anyway, we had Mass every morning at 5:00—we started work at 6:00—and I served for him every day. Mass always meant a great deal to me. The Japanese also allowed the Archbishop of Manila to come into camp for Christmas Midnight Mass in 1943. He celebrated it with the prison camp priests, and many of the parishioners sang special songs for it. It was an extremely moving ceremony that even had our guards listening.”

Nolan’s sole contact with home consisted of one package he received in March 1944. His mother had sent numerous packages with food and information, but only this one came through. When Nolan opened the box, he burst out in anger upon seeing a deck of cards and little more. “Man, did I cuss them out! Here I was starving to death and they send me a deck of cards, which I needed like a hole in the head. A couple of weeks later one of my friends asked to borrow them so he could start a game. We opened the deck, and in between the cards were five pictures showing my parents, my two brothers, and three sisters. I had been cussing out Mom, when here she had carefully hidden the photos, then sealed the package again.”

Nolan vividly remembered so many details because he kept a diary, a forbidden activity that could have resulted in his death if caught. He hid the pages in the palm leaves that formed the barracks roof, and since the tropical heat and humidity rotted the paper, he had to recopy the manuscript several times.

After Lipa, in March 1944, Nolan was moved to Camp Murphy near Manila. Conditions worsened, with rotted potatoes forming the main staple. This was where Nolan also had to run the gauntlet.

“The Japanese put an alcohol mixture made from sugar cane into their trucks to supplement their low supplies of gasoline. Well, the guards couldn’t figure out why their trucks kept running out of fuel until one day they caught some prisoners underneath the trucks eagerly filling their canteens with the stuff. It tasted sort of like alcohol, but whenever we belched we could taste gasoline. Anyway, the camp commandant forced all of us to run a gauntlet, which had 25-30 Japanese soldiers on each side, armed with clubs and rifles. I got almost to the end before collapsing, and I couldn’t walk for three days because of the blows to my spine.”

A Slim Hope for Rescue

The men received little outside help during their years in captivity. The International Red Cross visited from Manila to check on camp conditions, but the Japanese always knew about it ahead of time and cleaned up the camp before they arrived. When the inspectors left, everything returned to normal.

A group of Catholic nuns from a nearby convent school provided greater assistance. Nolan helped carry materials into the convent for a two-week stretch, “and as we walked by the nuns, suddenly from under their long-sleeved habits came rice balls in banana leaves or some other kinds of food. They endangered their lives to help us, and I never forgot that. For many years after the war I mailed bundles of clothing to this convent as a way of repayment.”

September 21, 1944, proved to be one of Nolan’s most memorable days, because on that day American aircraft bombed Camp Murphy. “Boy what a feeling that was! We were hollering and screaming and laughing because finally our side was here.”

Their jubilation lasted but one day. On September 22, the prisoners headed to Bilibid Prison in Manila in preparation for shipment to Japan. Thus began Nolan’s most frightening moments of his captivity—his sojourn in the “hell ships.”

“In early October we were taken to some ships in Manila Bay for transport to Japan. I was in a group of about 2,000 prisoners that was to board the first freighter out, but for some reason another group was put on and we went on the second ship. That first ship, the one I was to be on, was later bombed and sunk by American planes.

Prisoners Drank Blood to Quench Their Unbearable Thirst

“We started with 11 ships, but only three were left by the time we got to Formosa. American planes and submarines got the rest. One time a Navy guy in our hold could actually hear the pings of an American submarine looking for us, and once on deck I saw torpedoes go right in front of and right behind us.

“Most of the time we all spent below decks, in terribly hot conditions with little or no water. I saw guys so thirsty they tried to lick perspiration from the hull’s side. Some guys even killed men in their own group so they could drink the blood to ease their thirst, but other prisoners usually took care of them and killed them in retaliation.”

Nolan’s ship first stopped in Hong Kong, where it came under attack from American B-24 bombers. The ship rattled and swayed at the moorings from close explosions, but emerged unscathed. After the war Nolan discovered an amazing coincidence—his younger brother, John, had been a pilot of one of those bombers. “So I was almost killed by my own brother. We verified that by checking with official government records.”

The ship departed on October 21 for a three-day voyage to Formosa. In the miserable conditions below decks, 37 more men succumbed before the vessel arrived at its destination. A three-month sojourn in Formosan camps led to another ocean trip, this time to Japan in a ship previously used to transport horses. The vessel reeked from the horse manure still littering the hold.

Nolan arrived at Smelter Prison Camp near Kosaka, Honshu, in northern Japan on January 30, 1945. With the war going badly for Japan, conditions worsened for the prisoners. “I worked in a copper smelter until the surrender. The work was harder, the guards crueler, and we arrived in four feet of snow and six below zero temperatures wearing only the tropical clothes we had from the Philippines, plus an overcoat. We had little heat, and the food was much worse because our Navy had so drastically reduced the flow of supplies to Japan. Even the Japanese were starving.

“That copper factory was dangerous, too. Once, waste material from a furnace near me exploded and I caught on fire. The injury caused a bad infection in my right thigh, but there was little medical care available. All the Japanese did was stuff rags in the infection to keep it open, then tear out the rags. I had little black specks work their way out through my skin for 10 years after.”

Since the camp stood far to the north, it avoided the increasingly heavy American bombing offensive against the Home Islands. Rumors filtered in of drastic devastation in southern cities, especially at Tokyo and Yokohama, but no one knew if they could believe the tales. They hoped and prayed that the war’s end would soon arrive and save them from possible death.

Relief and Excitement at Long Last

On August 17, 1945, the men knew something was afoot when the guards told them to remain in their barracks instead of heading for work. The next day they received additional grain to eat, and two days later a Japanese captain broke the news that the long conflict, and their incarceration, had ended. “We were so happy we couldn’t believe it. Some guys went looking for guards to get revenge, but they had already split.”

American aircraft flew over the camp on August 26 and dropped containers of badly needed food by parachute. With the parcels was a note requesting that the men let them know what they most needed by placing large signs on the ground. A Roman numeral I indicated they most needed food, Roman numeral II meant medicine, and Roman numeral III signified clothes.

“Food, newspapers, and clothes were dropped to us on August 27, along with another note telling us to place one man in the center of the parade ground to indicate every 50 prisoners. We had about 350, so we put seven men there. The next day B-29s bombed us with 50-gallon drums of supplies, and they continued to do this until we got out.

“I remember one B-29 crew in particular that dropped a note on August 31. It stated, ‘We have flown over 3,500 miles to bring you these supplies. We enjoy doing what we can to bring you aid and comfort. Look for us again. We hope we can all be back in the U.S.A. again soon.’ It was signed ‘SLICK DICK crew, Capt. Edmund M. Wares.’”

On September 11, a train took Nolan and a group of ex-prisoners to Sendai, Japan, where he met the first American soldiers outside of captivity. After a brief stint on a hospital ship where doctors treated him for lice and fleas, Nolan left Tokyo aboard a C-47 transport bound for Clark Field in the Philippines.

“We had a mess sergeant in the Philippines who wondered why all his food kept disappearing. He didn’t know we were prisoners of war, so I told him, and from then on he kept the mess open all the time so we could keep refilling our food trays.”

Nolan Struggles to Adapt to a Normal Life

A transport ferrying Nolan and other former captives across the Pacific left the Philippines on October 2. Excitement built as the ship slowly inched its way across the immense ocean until finally, after nearly four long years living in misery, Nolan sighted San Francisco on October 20. Following brief stays in two hospitals for medical examinations, Nolan headed home with his parents and one brother.

Although back in Michigan and surrounded by loving family and friends, Nolan’s return brought its difficult moments as well. “The first month home was especially hard to handle because my nerves weren’t what they used to be, and I had all kinds of people visiting. Mom had this whistling teapot that went off one morning. I went hysterical because I thought bombs were being dropped, so Mom got rid of the teapot. I didn’t want to be around a lot of people, and I didn’t want anyone telling me what to do. I wanted to do what I wanted to do when I wanted to do it.”

Struggling to Forgive

Nolan eventually returned to the job he held before the war, a splicer for Michigan Bell, and enjoyed the comradeship of people at his local Catholic church, at work, and in his neighborhood. Putting behind him the horrors of confinement, he successfully resumed a normal life.

Through the years Nolan suffered from various physical ailments brought on by his time in prison camps. Stomach problems, caused by lack of nutrition, plagued him, and the severe beatings issued by guards took their toll on his heart, liver, kidneys, and back. Most of all, the mental images of his ordeal hounded Nolan. “I experienced plenty of nightmares in which I was always fighting somebody who was chasing me. I’d kick my feet and swing my arms, and holler indistinguishable words, then when my wife would wake me I’d tell her, ‘It’s the damn Japs.’ Eventually a doctor in a veterans’ hospital near home helped me get over them.”

Nolan retained few harsh feelings toward the Japanese. In 1965 he even returned to Japan for a visit, where he and his wife joined a tour group. “We were on a tour bus with some other Americans, who started to get on the tour guide—a young Japanese who spoke English. I told them to lay off, that the tour guide wasn’t even born when we endured the prison camps.”

Sergeant William Nolan is a exemplary man that will live with me for my entire life. I believe Sergeant William Nolan’s deep and profound Faith and love of life is testimony of his intrepid survival . Peace and Respect to all World War Two Veterans.

My cousin PFC Lex Lillard was a POW at Cabanatuan. His remains were identified through DNA and finally returned to his family. I wish I could find out more about him.