by Eric Niderost

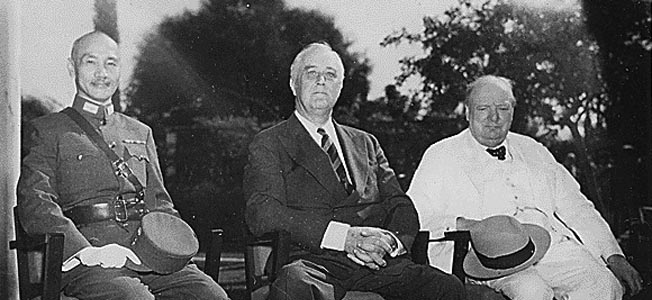

The Chinese Army of 1932-1937 reflected the political and social upheaval that plagued the country during this period. By 1930, the various petty warlords that had ruled parts of China were effectively defeated, their private armies scattered or incorporated into national formations. General Chiang Kai-shek and his Nationalist Party (Kuomintang) ruled China from Nanking, while Mao Zedong’s Communists were virtually autonomous in Shensi province.

[text_ad]

German Advisors Helped With Dual Threats

Although Chiang’s preoccupation with the Communists bordered on obsession, he was not unaware of the Japanese threat. German military advisers were brought in to assist Chiang in modernizing his forces. General Hans von Seeckt and General Alexander von Falkenhausen soon helped the general draw up a plan of action.

The task was formidable, and at times seemed impossible. Besides the autonomous Communist Chinese forces, the Chinese Army was a “patchwork quilt” of disparate elements barely stitched together by the fragile threads of common language and culture. On paper, China boasted an army of about 1.5 million men, but in terms of training and equipment, the quality varied greatly.

An Elite Force By Chinese Standards

The Central Armies were the core formations, some 300,000 troops that were generally better equipped and trained than the bulk of the Chinese armed forces. The Central Armies included several elite units collectively called the “Generalissimo’s Own,” 80,000 German-trained and largely German-equipped soldiers. The “Generalissimo’s Own” were the best troops in the Chinese Army and included the famed 87th and 88th Divisions. Although most Western observers considered even the “Generalissimo’s Own” as inferior to the Japanese, events around Shanghai were to confound the so-called experts. For three months, from August 13 to November 9, 1937, the 87th and 88th held Shanghai against the odds.

Uniform Variations

A soldier of the elite 87th or 88th fighting that torrid and bloody summer wore a light, five-button khaki tunic with two large breast pockets. A unit patch was sewn on the left breast, bordered in infantry red. The standup collar tabs showed gold rank triangles against a branch color background—red for infantry, yellow for cavalry. There were many design variations based on rank. For example, a private first class would sport three triangles on this collar tab; a corporal one triangle with a black line through it.

The soldier wore khaki trousers made of the same light cotton material as his tunic, with cotton puttees wound around the lower portions of his legs. German influence was heavy, most obviously in the Model 1935 German steel helmet that members of the 87th and 88th wore. Of course, the swastika emblem was replaced by the white sunburst pattern of the Nationalist Chinese government.

Chinese Army Outfitted By Foreigners

The main weapon of a Chinese soldier of the 87th or 88th was a Chinese-made version of the Mauser 88k, popularly known as the Chiang Kai-shek rifle.

The main weapon of a Chinese soldier of the 87th or 88th was a Chinese-made version of the Mauser 88k, popularly known as the Chiang Kai-shek rifle.

They may have given a good account of themselves, but the 87th and 88th were virtually destroyed in the vicious three-month contest for Shanghai.

The Chinese also took the first tentative steps toward creating an armored force to counter Japanese tanks. By 1936, China had three tank battalions—scratch-built formations—whose equipment came from a variety of foreign sources. The Carden Loyd Model 1931 amphibious tank was the backbone of the Chinese First Tank Battalion. This 3.1-ton British tank was armed with one Vickers .303 machine gun, but was often mechanically unreliable. The Chinese also purchased some Vickers six-ton tanks.

Other tanks in the Chinese arsenal included the Polish FT-17, French Renaults, and the Italian CV.33 two-man tankette. German advisers in China made sure that there was some German armor in this international “stew.” A small number of PzKpfw 1As served with the Chinese Third Tank Battalion. The First and Second Tank Battalions were destroyed during the Shanghai fighting, while the Third was wiped out defending Nanking.

Chinese Landscape Hard Going For Japanese Tanks

Ironically, the Japanese Type 89 medium tanks fighting in and around Shanghai found the going rough. The Yangtze River region is broken up with lakes, canals, and small streams, and even light tanks are ill-suited for narrow streets and rubble-clogged avenues.

Chiang Kai-shek and his German advisers recognized that the Chinese Army was inferior to the Japanese in training and equipment, and was likely to stay inferior for some years to come. For all his faults, the nationalist leader was a realist, able to accept and even come to terms with this unpalatable fact. The only viable strategy was a Fabian one: to retreat up the Yangtze Valley and trade space for time.

The Chinese Make Their Stand At Shanghai

In this scenario, first sketched out as early as 1936, the Chinese would conduct a fighting retreat, inflicting as many casualties as they could. It was hoped that overstretched supply lines and a series of Pyrrhic victories would finally make the Japanese abandon their efforts to conquer China.

Chiang Kai-shek diverted from this script only once, when he chose to directly confront the Japanese at Shanghai. Shangai was the most cosmopolitan city in China, and its large foreign presence assured Chiang that China’s heroic stand would have an international audience. When Shanghai’s battles elicited sympathy, but little concrete support, Chiang reverted to the original scenario. The Chinese retreated to Chungking, and in the process managed to inflict a series of very real, if inconsequential, victories over the Japanese.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments