By Sam McGowan

If there was a name of a prospective target that caused Allied airmen in the European Theater of Operations to blanch in the fall of 1943 and the spring of 1944, it was Ploesti.

Schweinfurt and Regensburg may have been feared names for Eighth Air Force crews flying from England, but the Romanian city and oil-refining complex had the dubious honor of being the second most heavily defended target in Europe. The first was Berlin and the third was Wiener Neustadt in Austria.

Ironically, the Allies were not aware of the defenses concentrated around the refineries until they found out the hard way on August 1, 1943. Perhaps they should have anticipated that the Germans would mount an aggressive defense of the refinery complex. After all, British Prime Minister Sir Winston Churchill thought the refineries so important that he believed their destruction would deal a “knockout blow” to the German war effort.

The Ploesti oil-refining complex produced 60 percent of the petroleum products used by the Axis in Europe; the remainder was spread over many small complexes in Germany and the occupied countries. Early in World War II, the Allies identified Ploesti as one of the most important targets in Europe. The problem was that at the time it lay out of range of all of the British and American bombers except one, the Consolidated B-24 Liberator, and until the summer of 1943 there were not enough of them to make an effective strike. The Soviet Air Force had bombers that could reach Ploesti and did attack the refineries a few times, but with negligible results.

Japan’s Response Leaves 250,000 Chinese Dead

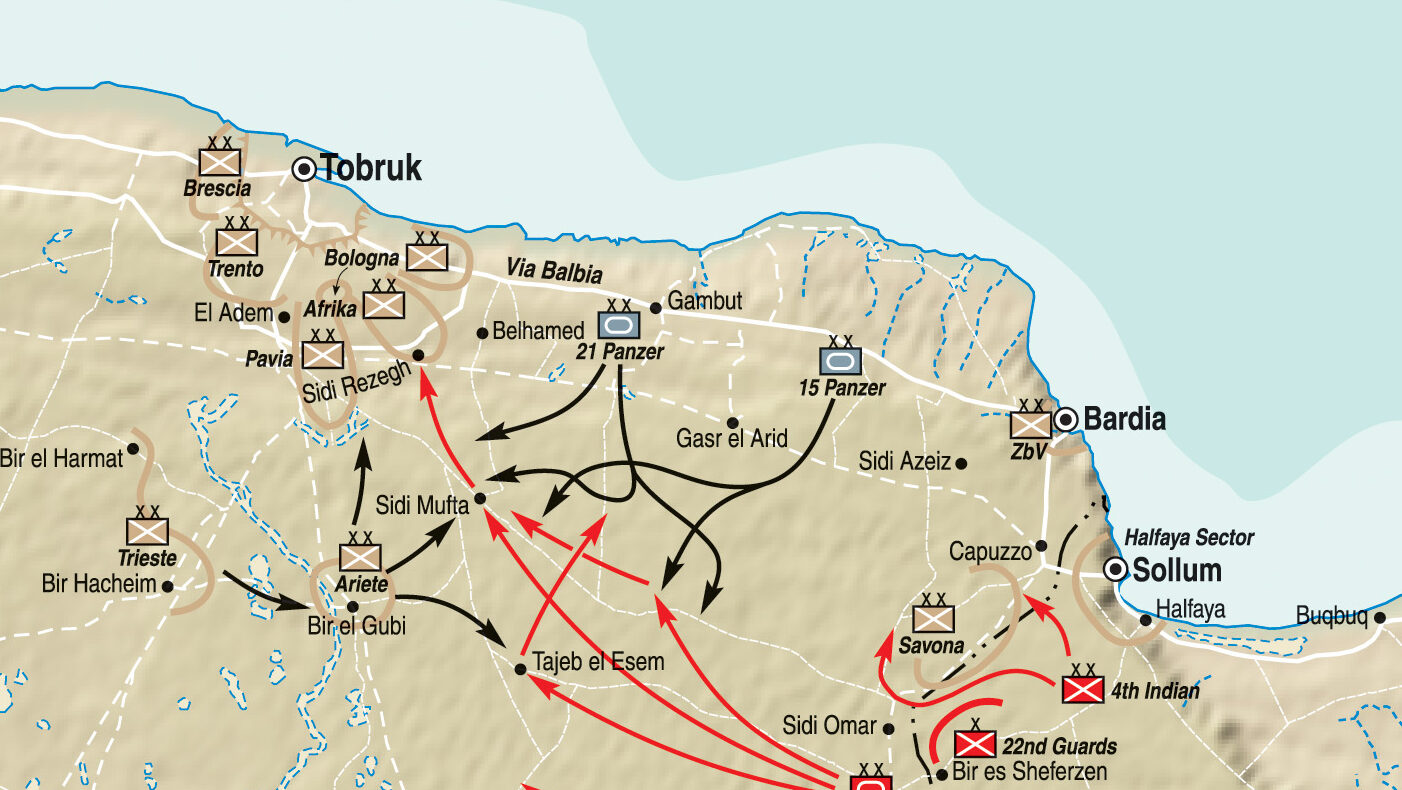

The Germans were also well aware of the distances involved and considered the city’s location in the foothills of the Transylvanian Alps to be Ploesti’s best defense. That is, until June 11, 1942, when a small force of American Liberators made an ineffective attack on the refineries. The Liberators were from the Halverson Detachment, a special mission that had been organized early in 1942 for deployment to China to serve as the nucleus of a bomber force that would mount a sustained bombing campaign against the Japanese Home Islands. But the plan for a strategic bombing campaign was thwarted when Japan responded to the militarily ineffective Doolittle Raid by mounting an offensive in China and capturing the regions where the Allies planned to establish bases. The Japanese also killed more than a quarter of a million Chinese civilians in the process. Without a mission in China, the Halverson B-24s were halted in Africa and sent to Palestine to mount a strike on Ploesti.

The British Royal Air Force had been working on a plan to bomb the oil refineries at Ploesti for more than two years, and when HALPRO, as the Halverson Detachment had been designated, arrived in Egypt, their plan was given to the Americans. It called for a strike force to depart from Egypt and fly over the Aegean Sea for a rendezvous near the target at daybreak, with a return to Egypt over the same route.

It was decided instead to return to Habbaniyah, an airfield in Iraq, even though that would mean violating the neutral airspace over Turkey. Late on June 11, 13 B-24s took off from Fayid, Egypt. Twelve airplanes proceeded to the target individually and arrived over Ploesti at dawn. Some crews bombed through a 10,000-foot overcast, while others descended below the clouds to drop their loads. The force was not intercepted, and all 13 crews made it to safety, with four landing at Habbaniyah as planned, three others landing at other fields in Iraq, and two at Aleppo, while four were interned in Turkey. Another crash-landed.

In spite of the lack of enemy action, the toll on Allied aircraft was heavy since five of the 13 airplanes were removed from further combat use. Although there was little appreciable damage to the refineries, the HALPRO attack was a significant mission as it was the first American strike against a strategic target. The Tokyo Raid a few weeks before had been more for propaganda value than for military purposes. The HALPRO raid also signaled the beginning of U.S. Army Air Forces strategic bombing of European targets; however, it would be more than a year before American bombers struck Ploesti again.

American Bomber Squadrons Convene in the Middle East

The HALPRO detachment was soon joined by Boeing B-17 Flying Fortresses that had been diverted to the Middle East from India. The combined force joined British Royal Air Force Liberators in strikes on Axis targets in North Africa and the Mediterranean. By July 20, American bomber strength in the theater consisted of 19 B-24s and nine B-17s, all under the command of Maj. Gen. Louis H. Brereton, who had recently arrived from Asia. The commander had arrived in the Middle East by a circuitous route, as he had previously commanded American air forces in the Pacific, then had moved to India to organize and command the Tenth Air Force.

Rapidly changing events in the Middle East had led the War Department to move Brereton and much of his China-Burma-India command, including the squadron of B-17s, to Palestine. On July 25, Brereton’s bomber strength began increasing as an advanced element of the 98th Bomb Group arrived at Ramat David, Palestine. By August 7, the entire 98th Group was in the Middle East.

Later in the year, the 376th Bomb Group would be organized in Palestine as a command unit for the remnants of the HALPRO detachment, most of whom had been replaced by new arrivals from the States, and the unattached Liberator squadrons that had deployed to the region. The two B-24 groups soon became the bomber command of the new Ninth Air Force, which was organized in Egypt under Brereton in November 1942.

While Brereton’s Ninth was taking shape in the Middle East, the Eighth Air Force in England was building up its bomber strength for a sustained campaign against targets in Western Europe. Although the bulk of the Eighth’s heavy bomber strength was made up of B-17 groups, it also included two heavy bomber groups equipped with B-24s: the 93rd Bomb Group, which arrived in England in early September 1942, and the 44th Bomb Group, which arrived in England in October.

During the winter of 1942-1943, three squadrons of the 93rd were on detached duty in Africa, serving initially with the newly created Twelfth Air Force in support of the Allied invasion of North Africa, then moving to Libya to work under the Ninth Air Force. The 93rd returned to England in early 1943 but it would soon be back in Africa—and Ploesti would be the reason.

Operation Statesman, Soapsuds, and Tidal Wave

At the Casablanca Conference in early 1942, Churchill had stressed the urgency of a bomber offensive against Ploesti, but the lack of resources placed any plans for an attack on hold. American planners had been studying Ploesti as a potential target since right after Pearl Harbor, but the HALPRO effort in mid-1942 had been the only effort other than the Soviet attempts.

In April 1943 General Henry “Hap” Arnold, commander of the U.S. Army Air Forces, ordered his staff to revive the already-developed plans for an attack on the Ploesti oil fields. Two plans were set forth. Lieutenant Colonel C.V. Whitney had formulated one for a medium-scale high-altitude attack to be launched from Syrian bases, while Colonel Jacob W. Smart had conceived the idea of a massive low-altitude attack launched from the Benghazi, Libya, area. In the end, Colonel Smart’s idea was accepted and given the code name Operation Statesman. The name was later changed to Operation Soapsuds, then finally to Operation Tidal Wave.

As a result of the emphasis placed on high-altitude, daylight, “precision” bombing by the Eighth Air Force, to many the concept of using four-engine bombers at treetop altitudes was preposterous, even suicidal. However, low-altitude attack was a common tactic of the pre-war Air Corps, and using heavy bombers at low altitude was not unprecedented in 1943. In the Southwest Pacific, light, medium, and heavy bombers had begun using treetop tactics with great success, including wavetop “skip-bombing” attacks against Japanese shipping by B-17s as well as smaller B-25s and A-20s. In fact, treetop attack would be a mainstay of the post-war nuclear Air Force as military planners concentrated on tactics that allowed penetration of enemy airspace “below the radar screen,” popping up to a higher altitude to drop bombs, then returning to treetop altitudes in an escape maneuver.

Planning for Soapsuds had called for a formation of four-engine bombers to approach their target at treetop altitudes and to drop delayed-action bombs without climbing. The reasoning behind the plan was that not only would the bombers achieve the element of surprise, but at such low altitudes their bombing accuracy would be far greater than high- and medium-level bombing. The low-flying airplanes would also be immune to fighter attack from below, but they would be in range of everything from slingshots to deadly antiaircraft weapons.

Rehearsing the Bombing Raid

The distance to the target from available bases meant that only the Consolidated B-24 Liberator could be used for the mission. The famous B-17 was available in greater numbers at the time, but the mission was well beyond its capabilities. At the time, there were only two B-24 groups assigned to the Ninth Air Force, which was given responsibility for the mission. To increase the size of the striking force, the two Eighth Air Force B-24 groups were transferred to Africa for a period of temporary duty, and a third group, the 389th, which was originally scheduled to move to England, was diverted to Africa for the mission. General Brereton was in charge of conducting the operation, and it was his decision to use the low-altitude rather than the high-altitude plan. Colonel Smart was also sent to Africa to assist in mission planning. Recently promoted Brig. Gen. Ted Timberlake, the former commander of the 93rd Bomb Group, would also play a role in the planning.

In June 1943, the two Eighth Air Force B-24 groups were pulled off combat operations and placed on training status. The crews were sent out on practice missions at treetop altitudes over the English countryside, causing much speculation among the crews about the expected target. In late June, the 44th and 93rd left England for Libya, and by July 3 all of the groups were in place, just in time for the invasion of Sicily. The newly arrived Eighth Air Force groups joined the Ninth Air Force groups, attacking Axis targets in support of the Sicily invasion while continuing the low-altitude practice missions over the Libyan desert. Targets for the combined B-24 force included Naples and Rome, which was bombed for the first time on July 17.

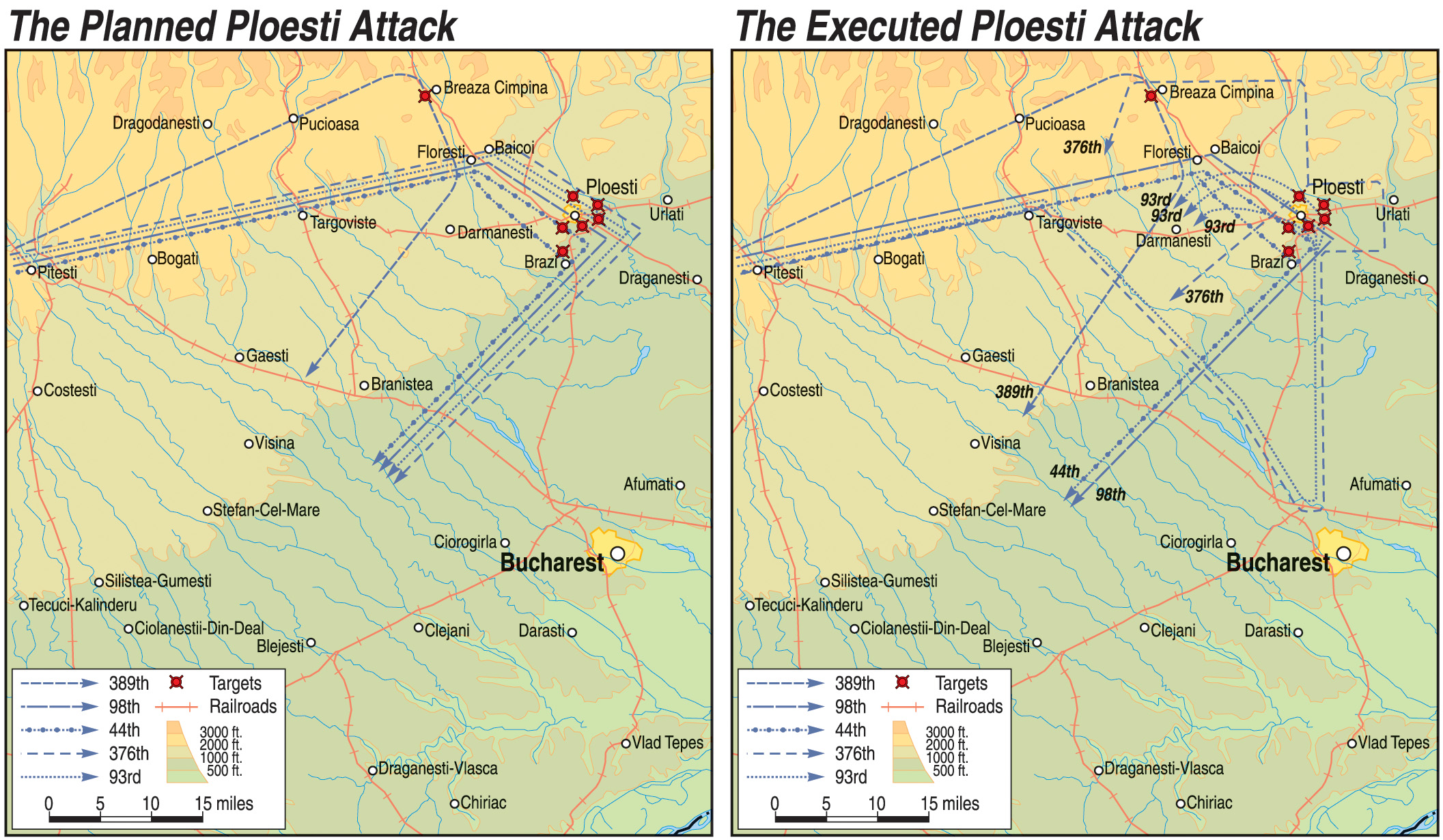

The plan for Tidal Wave called for certain key installations in each of the nine major refineries to be hit, on the assumption that if they were destroyed production in the entire complex would be interrupted. More than 40 objectives were grouped into seven general targets, five of which were at Ploesti itself with the other two at Brazi, which was adjacent to the city, and at Campina, a town eight miles away.

177 airplanes, 500-1000 Pound Bombs, and Clusters of Incendiaries

The original plan called for 154 airplanes, but the final mission totaled 177. Each of the five groups was assigned its own targets. The 376th, which would be the lead group, was scheduled to hit White I, the U.S.-owned refinery. The 93rd would follow the 376th and was assigned White II and White III, which included three refineries. The 98th was assigned to hit the two refineries in White IV, the 44th was assigned to White V and Blue, the latter being the refinery at Brazi. The rookie 389th was assigned to break off at the Initial Point (IP) and attack the Campina complex, which was designated as Target Red.

Ordnance for the mission was conventional 500- and 1,000-pound high-explosive bombs supplemented by clusters of incendiaries. All were armed with delayed-action fuses varying in time from one to six hours for the airplanes in the first wave to 45 seconds for those in the last wave. Each airplane was fitted with extended-range tanks in the bomb bay that increased their fuel capacity to 3,100 gallons. The Norden bombsights were removed and replaced with a special low-level bomb aimer. Some of the B-24s were modified with fixed, forward-firing machine guns that were controlled by the pilot to add to the firepower of the bomber’s normal complement of .50-caliber weapons.

After the Rome mission on July 19, all of the B-24 groups were taken off combat operations to train for the low-level mission that was scheduled for August 1. During the interim before the mission, each crew practiced low-level flying and bombing a dummy target from minimum altitude. The pilots, navigators, and bombardiers familiarized themselves with all the details of the mission—the route, their assigned targets, expected defenses, and sand-table models of the targets themselves. Ploesti lies in the foothills of the Alps and the route to the target would involve flying over various types of terrain, ranging from desert sand along the Mediterranean to the mountainous Balkans.

The Tidal Wave Approaches

Early on the morning of Sunday, August 1, 1943, the 177-plane formation of Tidal Wave began launching from the airfields around Benghazi. The first casualties occurred when one of the heavily laden bombers clipped a concrete power pole with a wing after takeoff and exploded in a ball of flaming gasoline and hydraulic fluid. Unknown to the American planners, the takeoff was monitored by German electronics’ equipment hundreds of miles away, designed to detect the electrical energy of the firing of hundreds of spark plugs.

The mission that had been planned in secrecy and was dependent on the element of surprise had already been revealed. Of course, the German defenders at first knew only that a large formation was taking off from the vicinity of Benghazi, but the entire progress of the mission would be monitored all the way to the target, and which would eventually be identified as Ploesti. Consequently, the men of Tidal Wave would encounter a well-prepared and organized defense that was primed and ready for their appearance.

Even though the Tidal Wave planners were not aware of the extent of the defenses at Ploesti, they were prepared to accept a casualty rate as high as 50 percent. Events would keep the casualty rates considerably lower, but they were nevertheless among the highest of any heavy-bomber mission of the war, far greater proportionally than those suffered by the B-17 crews that attacked Schweinfurt and Regensburg weeks later.

Considering the defenses, it was a miracle that the casualty rate at Ploesti was not higher than it turned out to be. In response to the HALPRO attack, the Germans and Romanians had built up a sizable force of fighters combined with heavy concentrations of antiaircraft guns all around the refinery complex. They had also organized an effective preparedness group within the refineries that was well versed in firefighting procedures and the disarmament of unexploded bombs.

Mounting Obstacles for Operation Tidal Wave

The formation suffered its second loss over the Mediterranean when one of the airplanes in the lead element of the 376th suddenly fell off on a wing and plunged into the sea. Not only were the airplane and crew lost, but the situation was magnified because the navigator was the lead for the first part of the flight.

In a discussion with author and former 93rd Bomb Group Public Information Officer Cal Stewart before his death, General Ted Timberlake revealed that Tidal Wave had been planned for different navigators to be responsible for leading the formation on different legs of the flight. He also revealed that there was another problem that prevented the attack from being carried out as planned.

For reasons that have not been fully explained, Colonel John R. Kane, the commander of the 98th Bomb Group and the lead of the second formation, allowed his formation to drop well behind the first formation, and thus disrupted the integrity of the mission. Various explanations have been offered for this failure. One is that the 98th’s planes were poorly maintained and their engines were not able to produce the power needed to keep up with the better-maintained airplanes of the England-based 93rd. This theory fails to take into account that the lead 376th was also based in North Africa and its planes were exposed to the same kinds of conditions and maintenance difficulties.

At any rate, the three trailing groups failed to maintain the proper airspeed and dropped so far behind that the tail gunners in the 93rd airplanes could not see them. The gap was further increased when the formation reached land in the Balkans and found a line of summertime thunderstorms building over the mountains. Colonel Keith K. Compton, the lead pilot for the formation and the commander of the 376th group, elected to weave his way between the clouds at an altitude just high enough to safely clear the mountains.

Compton was accompanied by Brig. Gen. Uzal Ent, the IXth Bomber Command commander and the mission commander of Tidal Wave. Kane elected to perform a weather-penetration maneuver, which involved leading the formation into a 360-degree wheeling turn with elements breaking off to penetrate the weather. The maneuver cost even more valuable time, and the time to reassemble on the other side of the mountains added to it.

The decision to climb to higher altitude not only contributed to the separation due to the loss of airspeed for the climb, but it also allowed the German listening posts to more effectively pinpoint the location of the formation and contributed to their ability to identify Ploesti as the intended target. It also made the bombers detectable by German radar. The Germans identified Ploesti as the target and alerted the city’s defenses. Fighter pilots rushed to their airplanes and took off while antiaircraft gun crews manned their positions.

“We’re Bombing That Target, No Matter What.”

Tidal Wave was a summertime mission, and the pilots and navigators in the formation found themselves in typical August weather, which meant haze and scattered showers, especially along the Alps. As the lead formation entered Romanian airspace and neared their target, they found themselves in an area of summer showers.

The IP for the mission was the town of Pitesti. It lies about 50 miles from Floresti, which was the final Initial Point at which the formation was to turn southeast toward Ploesti and the refineries—with the exception of the 389th, which was to take a more northerly course out of Pitesti to set up for an attack from the north against the Campina complex. On course between Pitesti and Floresti is the small town of Targoviste. General Ent and Colonel Compton mistook Targoviste for Floresti and turned short of the final IP, on a course that would take them to Bucharest, the Romanian capital and the headquarters for German and Romanian air defenses.

When the mission lead made the wrong turn at Targoviste, many of the navigators in the following airplanes recognized the error but continued along behind their commander. As the formation approached Bucharest, Lt. Col. Addison Baker, commander of the 93rd, apparently saw the smokestacks of Ploesti to the north, broke away, and turned toward the target. Ent and Compton also turned north toward Ploesti, but when they encountered heavy antiaircraft fire they broke off to the east in hopes of finding a hole in the defenses.

The lead formation never did make it over the target. Baker, however, ignored the heavy fire and headed directly for Ploesti with the other 93rd pilots right behind him. The night before the mission he had told his men they were going to bomb the target “no matter what.”

After reaching a point northeast of the refineries and realizing that there was no easy way in, Ent ordered the crews to bomb “targets of opportunity.” Most of the 376th planes ended up dropping their bombs on the countryside, except for one six-plane element led by Major Norman Appold, which bombed the Concordia Vega refinery, originally assigned to other elements of the 376th.

The Entire B-24 Was Set Ablaze

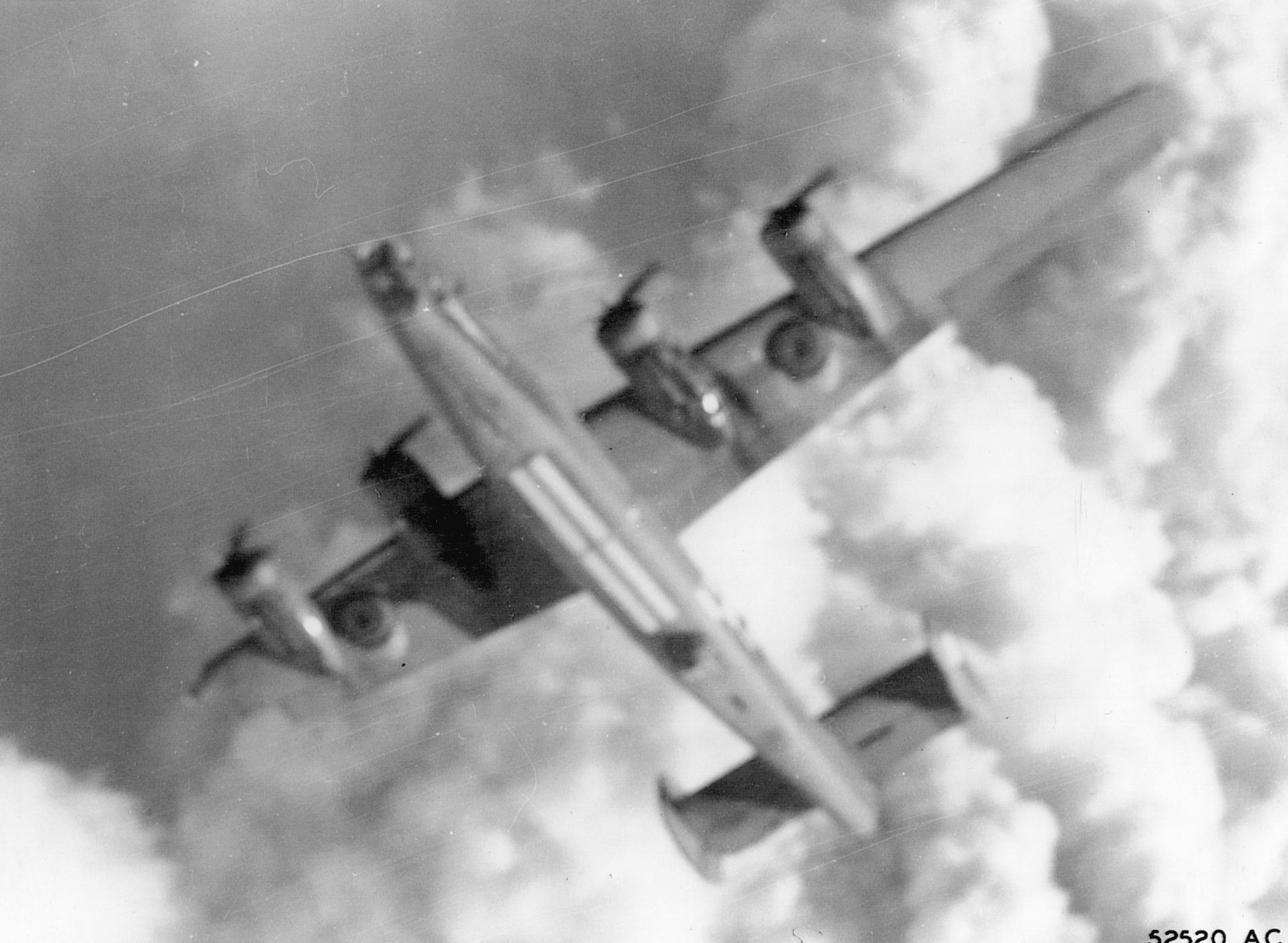

The 93rd Bomb Group did not follow Ent and Compton to the east of Ploesti but went directly to the target area from the south. As the formation approached the refineries, it encountered intense ground fire. The three airplanes of the lead element were all hit, and all went down over the target. Lieutenant Colonel Baker’s B-24 was set on fire, yet he continued to lead his group over Ploesti as he had said he would. Survivors of planes flying near their leader reported that his entire B-24 was on fire, and flames could be seen inside the cockpit windows. The stricken Liberator fell off on a wing and went into the ground.

Baker and Major John Jerstad, a veteran 93rd pilot who was flying in the copilot’s seat, were both awarded the Medal of Honor posthumously. All in all, no less than five Medals of Honor were awarded to Tidal Wave participants, with three awarded posthumously. Eleven 93rd Liberators were lost over their targets, more than 10 percent of the group’s total losses for the entire war. In spite of the losses, the 93rd successfully bombed the targets and caused tremendous damage. Unfortunately, the targets they hit had been assigned to the 98th and 44th groups, which were still trailing far behind.

By the time Colonel John R. “Killer” Kane finally arrived over Ploesti—after flying the correct course—the refineries were a sea of flames and exploding ordnance. Most of the fires were in storage tanks that had been set alight by tracers from the 93rd gunners, and by the defenders’ own antiaircraft fire. All of the remaining antiaircraft sites were at full alert, and the 98th and 44th encountered the same heavy fire that had decimated the 93rd before them.

The 98th and 44th bombed their assigned targets, even though they had already been hit by the 93rd. The only 376th airplanes to actually bomb the target were the six-plane element led by Major Norm Appold. Kane and Colonel Leon Johnson, the commander of the 44th, were both awarded the Medal of Honor. Their awards were the only ones that were not posthumous.

54 Planes and 532 Airmen Dead or Captured

The 389th Bomb Group, the least experienced of the five groups, carried out the most successful and most destructive bombing run. Colonel Jack Wood led his group on the correct course from the IP, and it came over the Campina refinery as briefed. The Campina refinery was the only target that was destroyed. It was put out of action for nearly a year and never did return to full production.

The 389th suffered the lightest losses over the target, with six B-24s shot down. One of the pilots, 2nd Lt. Lloyd Hughes, was awarded the fifth Medal of Honor for taking his stricken airplane into a wall of flame, even though it was trailing a stream of highly volatile aviation gasoline, to pass over the target and drop his bombs. Hughes’ airplane crashed while attempting to land in a stream bed.

As the surviving bombers came off the target, they found that they were still in the deep woods. The 98th and 44th groups were jumped by fighters and continued to take heavy losses all the way across Bulgaria. The 98th lost a total of 21 planes over the target and on the way home, while the 44th suffered 11 losses.

Ploesti was a very costly mission. When time ran out for all of the bombers to have returned home, nearly a third of the force was unaccounted for. The final tally for the mission was a loss of 54 planes, and 532 airmen were reported as dead or captured.

While the mission to Ploesti was the most dangerous of the war for the men who participated, the survivors who returned to Benghazi were soon back in action. TIME magazine photographer Ivan Dimitri, who was in Benghazi at the time, reported in his book Flight to Everywhere how Air Transport Command C-87 transports mounted an airlift of aircraft engines and other parts into Benghazi for repairs to the wounded airplanes. Less than two weeks after Tidal Wave, the combined Eighth and Ninth Air Force Liberator force attacked the aircraft factories at Wiener Neustadt.

Not Quite a ‘Knockout Blow’

The three Eighth Air Force B-24 groups left North Africa a few weeks after the attack, and Ploesti became but a memory for them as they returned to England. However, for some of the men in the 98th and 376th, Ploesti would remain a reality. The two groups became the nucleus of the new Fifteenth Air Force, formed as a second arm of the U.S. Strategic Air Forces in Europe, a command organization that was formed to conduct the American portion of the combined bomber offensive against Germany. The Ninth Air Force transferred to England to become a tactical air force for support of Allied invasion forces in Normandy, but its B-24s became part of the Fifteenth, along with the B-17 groups that had made up the Twelfth Air Force.

Tidal Wave had not struck the ‘”knockout blow” against the Ploesti oil refineries that Churchill had wished for during the Casablanca Conference, but it had inflicted major damage. An estimated 42 percent of Ploesti’s total refining capacity was believed to have been destroyed, along with perhaps as much as 40 percent of the cracking facilities. Thousands of gallons of gasoline and crude oil had been destroyed by the fires in the storage tanks. But the German and Romanian workers had reduced the potential damage substantially with the effectiveness of their disaster preparedness teams, which brought the fires under control, and with the courage of the bomb-disposal squads that had disarmed many of the delayed-action fuses. Ploesti became a major target for the Fifteenth Air Force.

The Fifteenth was activated on November 1, 1943, with Lt. Gen. James H. Doolittle as commander. Doolittle would move to England in a politically motivated transfer to take command of the Eighth Air Force, while General Ira Eaker moved to Italy. Initially the group consisted of four B-17 groups, the two former Ninth Air Force B-24 groups, and a combat wing of B-26s that had been part of Twelfth Air Force.

The War Department ordered the diversion to the Mediterranean of three B-24 groups per month in November, December, and January. These had been planned for England and the Eighth Air Force. Six other groups were planned for transfer to the Fifteenth in February and March, to bring the heavy bomber strength to 21 groups, of which about two-thirds were equipped with B-24s and the rest with B-17s. All of these would eventually be based on Italian soil.

In the spring of 1944, the War Department authorized the beginning of a campaign against the German oil industry, both petroleum and synthetic, as part of the combined bomber offensive. Because of its closer proximity to the oil fields around Ploesti, which still accounted for the major share of Axis oil in Europe, the Fifteenth Air Force was given the task of destroying both the refineries and the transportation system that moved the refined products to German forces.

The High Cost of Capturing Ploetsi

In March 1944, General Carl Spaatz, commander of the U.S. Strategic Air Forces, was authorized to order attacks on Ploesti. On April 5, Fifteenth Air Force B-17s and B-24s attacked marshaling yards around Ploesti. They repeated the attack on April 15 and 24. While all three missions were aimed at transportation facilities, many of the bombs fell within the refineries themselves, causing substantial damage.

Fifteenth bombers flew more than 20 daylight high-altitude missions against the Ploesti oil fields by June, while Royal Air Force Wellington bombers flying from Italy carried out four nighttime raids. The raids were costly for the Allies; German and Romanian antiaircraft and fighter defenses around the complex remained at a high level.

One of the most costly raids against the refineries was carried out on June 10, 1944, by 75 American twin-engine P-38 fighters, half of which were carrying 1,000-pound bombs while the other half served as escorts. Twenty-one of the P-38s were lost on the mission, with most falling to the deadly flak that claimed so many Allied bombers. Losses over Ploesti remained high until August 1944, when the strength of the German defenses began showing signs of weakness. By this time the refineries had suffered major damage and were effectively out of the war. Ploesti was captured by Soviet forces shortly thereafter.

Nearly every mission against Ploesti resulted in casualties, including Colonel Jacob W. Smart, the planner of the low-altitude mission of August 1, 1943, who was shot down over the target in a B-17 and taken prisoner. Fortunately his German interrogators failed to query him about America’s nuclear program, of which he was one of a handful of men with knowledge. By the time the refineries had been rendered inoperable, the Fifteenth Air Force had suffered the loss of 350 B-17s and B-24s and their 10-man crews. Ploesti had lived up to its reputation as the most heavily defended target in Eastern Europe.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments