By Eric Niderost

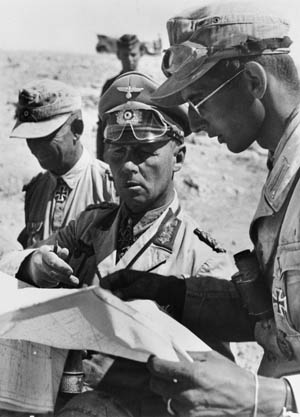

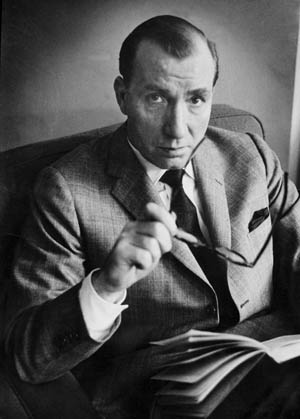

On April 15, 1942, Generaloberst (Colonel General) Erwin Rommel summoned his subordinate commanders of the Panzerarmee Afrika to a conference to outline his plans for the coming offensive against the British Eighth Army. The stakes were high, his proposals not without risk, but as usual Rommel exuded confidence. He was a familiar figure to his assembled officers, with his close-cropped hair, penetrating eyes, long nose, and narrow lips; a handsome, military face that was a perfect mirror of a personality that could be serious but also had a large dose of good humor. He was dressed in his Afrika Korps uniform, tan jacket with red general’s tabs on the collar, Knight’s Cross of the Iron Cross at his throat.

Rommel Called In To Assist The Italians

In this spring of 1942 the Germans and their Italian allies had been locked in a seesaw battle for North Africa, a struggle that had started in 1940 when the forces of Italian dictator Benito Mussolini attacked British-held Egypt from their bases in Libya. The Italian offensive was a fiasco, and the British soon gained the upper hand. The Italians had bitten off more than they could chew, and in an effort to get his fellow dictator’s chestnuts out of the fire Adolf Hitler dispatched Rommel and several German units, collectively known as the Afrika Korps, to North Africa in February 1941.

Rommel began an offensive that pushed the British back to the borders of Egypt, and although his successes proved temporary his brilliant maneuvers were the start of his legend as the “Desert Fox.” Late in 1941 the Germans were pushed back by a British counteroffensive, but in the spring of 1942 Rommel was ready once again to make a bid for victory.

Germans Faced Formidable Gazala Line

Indeed, the Panzerarmee Afrika was facing a formidable challenge. The British Eighth Army was deployed in a massive series of defenses known as the Gazala line, named for a town on the Mediterranean coast. Stretching some 40 miles from Gazala to Bir Hacheim to the south, the Gazala line featured an “archipelago” of strong points known as boxes, self-contained islands of resistance set in a sea of land mines and further protected by tangles of barbed wire. Each box had infantry supported by artillery and tanks, altogether hard nuts to crack.

Assault Plan Seeks To Trick British

But that was not all the Germans had to face. General Neil Ritchie, the British Eighth Army commander, placed armored and motorized units just behind the Gazala line, in theory a fast-moving, mobile defense that could counter any German thrust. Rommel had two options: He could launch a frontal assault in north of the center of the Gazala line, or he could try and outflank it to the south. A southern flanking move was more to the Colonel General’s personal tastes and inclinations; he could pivot on Bir Hacheim (in the process taking that strongpoint) then sweep north behind the Gazala line.

As the conference proceeded Rommel explained that he would make a frontal attack on the Gazala line—but that the attack would merely be a feint. Just behind the Gazala line was Tobruck, a fortress/port that had been a thorn in Rommel’s side in the previous year’s campaign. A frontal assault in the north would be the shortest route to Tobruck, a much-sought-after prize. Rommel hoped he could deceive the British into thinking his main effort would be in the north, while in reality the major offensive would be a surprise envelopment of the British southern flank.

While it was true Rommel’s failure to take Tobruck in 1941 was a bitter pill, he was not so obsessed with its capture that he lost sight of the overall strategic picture. In fact, he wanted to make it clear that Tobruck was not the only objective. “Die Englischer Feldarmee,” Rommel declared, gazing intently into the faces of his officers, “muss vernichtet werden, und Tobruck muss fallen!” (The English field army must be totally destroyed, and Tobruck must fall!) Rommel knew he was probably outnumbered by the British in tanks, but trusted that superior German tactics—and, hopefully, poorly coordinated enemy attacks—would redress the balance. The conference concluded and preparations were made for the coming offensive in spite of the ovenlike desert heat.

Rommel Admired By His Men

Rommel was already famous in the spring of 1942, and well on his way to becoming a legend. His men idolized him, because although he was a hard taskmaster he had a genuine affection for his troops and cared for their well-being. Certainly, if he was tough on them he was equally tough on himself. He shared their hardships and never asked them to do anything he wasn’t willing to do himself. Of solid middle-class origin, Rommel had little connection with the snobbish upper-class aristocrats one associates with the German officer corps. Although he naively thought Hitler was the savior of Germany, he was apolitical and certainly no Nazi.

As a general Rommel had an excellent grasp of strategy and tactics. A master of maneuver, he knew how to propel an army in rapid strokes. He was an inspiration to his men, often galvanizing them by personal example. Rommel was also flexible, one of the characteristics of a great general. If events proved his original plans faulty, he was capable of changing them with alacrity to meet changing conditions. On a personal level Rommel possessed a high degree of integrity. He bore the British no personal animosity, and stories of his fair treatment of prisoners are legion. Rommel’s fame was just as great among the “Tommies” as among the Germans, and it was his British enemies who gave him the sobriquet “Desert Fox.”

Beyond Tobruck, Rommel Eyes The Mid East Oil

In the spring of 1942 Rommel was looking beyond Tobruck, and even beyond the possible seizure of the Suez Canal in Egypt. The German general was a fierce partisan of the so-called “Plan Orient,” a geopolitical strategy bold in concept and intercontinental in scope. In early 1942 Hitler’s armies were in the Soviet Union, about to conduct a drive into the Caucasus to seize vital Russian oilfields. Plan Orient was an even bolder concept, calling for the Panzerarmee Afrika to seize not only Alexandria and the Suez Canal, but to continue on and roll through Palestine and the rest of the Middle East. Oil-rich Persia (Iran) and Iraq might fall, and the Panzerarmee would link up with German armies fighting in Russia.

In essence, then, Panzerarmee Afrika would be the southern arm of a great pincers movement, the German army in Russia comprising the northern arm. Once Germany was in control of Middle Eastern oil reserves, the war would be more than half won. It was a good plan on paper, but it presupposed continued German success in Russia and Axis control of the Mediterranean—two very tall orders indeed. In any case Plan Orient didn’t seem a pipe dream in the spring of 1942; even the British feared such a scenario.

Rommel’s Panzerarmee was a mixed force of both German and Italian units. Probably the most famous was the Deutsches Afrika Korps, or DAK, a formation whose name is indelibly linked to Rommel’s. In early 1942 the DAK was commanded by General Walter Nehring and consisted of two major formations, the 15th and 21st Panzer Divisions. Another German unit was the 90th Light Division. Sources seldom agree on specific numbers, but probably some 90,000 Axis troops faced 100,000 British. Rommel’s equipment was as multinational as his troops. Besides German and Italian weapons, he incorporated captured British guns and vehicles into the Panzerarmee Afrika. Rommel was even sent Soviet 50-mm and 76.5-mm artillery captured on the Russian front.

Tanks and armored vehicles were going to play an important role in the upcoming Gazala operations. The backbone of the German Panzer divisions was the Mark III tank, boasting thick armor but armed with a short 50-mm gun. Rommel also had 19 Mark III Specials with face-hardened armor and a hard-hitting long-barrel 50-mm gun more powerful than the short-barrel version. Italian tanks were obsolescent nightmares more lethal to their crews than to the enemy. With a delicious sense of irony Italian tank crews called their machines “self-propelled coffins.”

The British had several different kinds of tanks, including Matildas, Valentines, and Crusaders. The Crusader was armed with a two-pounder gun (named after the weight of the shell) but was plagued by mechanical troubles. The Valentine was an infantry support tank, but the queen of British armor was the Matilda Mark II. It was a strongly protected tank, with armor up to three inches thick, and was armed with a two-pounder gun.

In the desert war both sides had to battle the climate as well as the enemy. Even in May the heat was terrible, with temperatures soaring to 120°F. Water was scarce, and fierce dust storms scoured the desert floor with choking clouds of reddish grit. On May 5, while deep into the preparations for the coming offensive, Rommel took the time to note in a letter to his wife, “Hardly a day without a sandstorm.”

Commanding the Primary Strike Force

May 26 was designated x-day, the day Rommel’s offensive was scheduled to begin. As the final details were worked out, Rommel decided to have General Cruewell command the left wing that would stage the feint attack along the northern sector of the Gazala line—just where the British expected it. This northern feint, dubbed “Group Cruewell” after its commander, consisted of the Italian 10th and 21st Corps (infantry) stiffened by the German 15th Rifle Brigade, the latter detached from the 90th Light Division.

The main strike force of the Panzerarmee Afrika would be the right wing of the enterprise, commanded by Rommel himself. This strike or turning force would envelope the British southern flank then drive up the rear of the Gazala line. Rommel hoped that the British, deceived that the main thrust was the northern feint, would send their armor northward. Even if General Richie didn’t, Rommel was confident he could defeat any opposition the British could muster.

Main Attack Followed By Diversion

Rommel’s right wing was the Schwerpunkt, a “cutting scythe edge” of the German drive, a drive that was subdivided into three main components. The first component, largely the Italian Ariete Armored Division, was to take the Bir Hacheim box; the second component, the two Panzer Divisions of the DAK, was to execute “a rapid night march, advance around the Gazala line, to the Acroma area, then attack British forces from the rear.” The third component, the 90th Light Division and the Italian 20th Motorized Corps, was to detach itself and disrupt British supply lines.

Temperatures were already soaring when General Cruewell launched his diversionary attack about 2:00 pm on the afternoon of May 26. Italian and German infantry were supported by some German motorized units and backed up with a swarm of recovery vehicles. The vehicles kicked up long plumes of dust, a vital element in the overall ruse. In fact, the Desert Fox still had some tricks up his sleeve in the form of airplane engines and propellers mounted on trucks. These giant wind machines whipped up the desert sands into huge dust clouds, fostering the illusion the entire Panzerarmee Afrika was attacking. German artillery boomed in support, and British guns roared in counterbattery. The silent stillness of the desert was shattered in a cacophony of artillery bursts and chattering machine guns.

Night fell, the blazing sun sinking into a cushion of orange, and the sweltering heat was replaced by numbing cold. At 20.00 hours (9:00 pm, but accounts differ slightly on the precise time) Rommel issued the code word “Venezia,” the signal to launch the envelopment of the southern flank of the Gazala line. With this single command 10,000 vehicles rumbled forward under the pale light of a full moon, a mailed fist ready to roll up the British Army. The element of surprise was lost when some South African scout cars (part of the British forces) detected the move and radioed the information back to headquarters. Other units were urgent and spoke to the situation in no uncertain terms: A lieutenant of the 8th Hussars (part of the 7th Armored Division), reported, “It looks as if Jerry’s come with a Panzer Brigade.” There was a pause that must have seemed like an eternity, then the officer amended the statement: “There’s more than just a brigade, it’s the whole bloody Afrika Korps! Alert! Alert!”

An Initially Successful German Offensive

In the first hours of the German offensive Rommel was a happy man. The DAK steamrolled through the 3rd (Indian) Motor Brigade, and the 90th Light Division overran the headquarters of the British 7th Armored Division. British General Messervy was captured, although he escaped the next day. The British 22nd Armored Brigade also tried to stem the German flood, but were sent packing in short order.

When a German radio message asked where a Panzer division was, the headset crackled in reply “Rommel an der Spitze!” Rommel is leading! Rommel was leading, indeed, up with the forward elements of the 15th Panzer and right in the thick of the fighting. When the commander of the 15th, General von Vaerst, came up in his armored car, the company commander of the leading Panzer company asked “What is our direction?” Before the general could answer his adjutant replied, “Over there! That’s where Rommel is!” And sure enough, the commander in chief could be seen in the very front line, risking his life as if he were a company commander.

A New British Tank Inflicts Its Damage…

At one stage of the advance German Panzer commanders trained their field glasses on some squat, unfamiliar shapes on the horizon, unwitting witnesses to the battlefield debut of a new British tank. They were the American-built Grant Mk III, and their presence had been undetected by German intelligence. The Grants were not only well armored, but they boasted a 75-mm cannon as a main armament seconded by a 37-mm gun. The 75-mm gun on the Grant was a nasty shock to the Germans, since it outgunned any armor they could field in the desert. Unfortunately, the 75-mm gun was mounted in the hull, inside a sponson, not on a regular turret, so it had a limited traverse. The tank itself had to be positioned to aim the gun.

Even so, the Germans got a rude awakening from the Grants. As the opposing sides opened fire, a shell from a Grant scored a direct hit that reduced a Panzer Mark III to a flaming wreck before it could come into range to adequately return fire. Within moments another German tank exploded into an orange-yellow fireball, and then another. The British Grants were also wreaking havoc on German transport trucks that were ferrying supplies to forward units. It looked for a few breathless moments that the Grants might achieve a major breakthrough.

A Way to Stop the Tanks

All was chaos, with German trucks careening through the desert in a desperate effort to reach safety while British shells rained down. Amid the confusion Colonel Alwin Wolz of the 135th Flak Regiment and General Nehring suddenly found themselves face to face with Rommel. Never one to mince words, Rommel gave Wolz a dressing down that must have made the British shelling pale in comparison. The Colonel General felt the flak units were responsible for the German retreat and subsequent chaos because they had not yet fired at the advancing British armor.

Rommel was reminding Wolz that the 88-mm flak artillery, although technically anti-aircraft guns, made excellent anti-tank weapons. In fact, Rommel himself made that discovery during the Battle of Arras during the 1940 campaign for France. Wolz knew what had to be done and set to work at once, assembling 16 88-mm artillery pieces and lining them up in a “flak front.” At this juncture between 20 and 40 British tanks appeared some 1,500 yards from Rommel’s men. The Germans opened fire at 1,200 yards, and the Grants were literally stopped dead in their tracks. By nightfall of May 27 the battlefield was littered with the blackened shells of 24 Grant tanks.

15th Panzer’s Drive Gets Stranded

In general, British attacks were piecemeal and lacked coordination, which favored the Germans. Still, the Panzerarmee Afrika suddenly found itself in deep trouble. Not only were the Grants a surprise, but the existence of the British “box” at Knightsbridge—held by the 201st Guards Division—was completely unexpected. The Ariete Division had failed to take Bir Hacheim, and the 90th Light was isolated and under heavy RAF attack. As if to compound the difficulties, the 15th Panzer’s drive literally ran out of gas and was stalled near the Knightsbridge box. Rommel’s strike force was scattered and fighting hard.

It was left to the 21st Panzer to continue the drive north, and the division managed to climb an escarpment overlooking the Via Balbia or coast road. The heat was like a furnace, nearly unbearable to men in stifling metal tanks, and the battles were punctuated by sand storms so fierce they reduced visibility even as they stung faces and choked parched throats. The fighting continued through the 28th, but Rommel managed to personally lead a supply column to the stranded 15th Panzer Division. Since his original plan was failing, Rommel decided to consolidate all his forces in a defensive perimeter called the hexenkessel, or “Cauldron.”

Rommel Seeks Corridor To Cruewell’s Forces

Once the right wing of the Panzerarmee Afrika was secure inside the Cauldron, Rommel wanted to shorten his supply lines by punching a corridor west through British minefields to General Cruewell’s forces just beyond. Bir Hacheim was still holding out, which meant German supply convoys had to skirt around the southern flank of the Gazala line and continue on a long and perilous journey north to reach the beleaguered and now all but besieged Panzerarmee. Raiding sorties from the Bir Hacheim garrison were harassing German trucks, and before long British forces had virtually cut off supplies coming around that circuitous southern route.

Work on clearing a path through the British minefields began at once. But then, on the night of May 29/30, the Germans discovered a hidden British box near Sidi Muftah manned by the men of the 150th Brigade. The Sidi Muftah box threatened the western supply artery that the Germans and their Italian allies were so painfully clearing through the minefields. Clearing mines was a difficult enough operation, but soon heavy shelling from the Sidi Muftah box made the job even riskier. The 150th Brigade had to be eliminated.

Cruewell Captured By The British

The German woes mounted. At 8:30 am May 29 General Cruewell climbed into a Fieseler Storch (Stork), a light reconnaissance plane, to fly to the headquarters of the Italian 10th Corps. His pilot went the wrong way and the general found himself over British lines. The Storch was peppered by British machine gun fire and within moments the pilot slumped dead over the controls. Things looked bad, but the plane crash-landed without major damage and Cruewell was captured. It just so happened that Field Marshal Albert Kesselring had been visiting the front on a tour of inspection, and in the emergency he took over Force Cruewell.’

It was around this period—May 29/30—that the Panzerarmee Afrika was at its most vulnerable. It was a missed opportunity for the British. Both sides had suffered heavy casualties, and it is estimated that Rommel had lost one in three of his tanks. The British had been badly mauled, but Ritchie still had three British armored brigades on hand, and the 32nd Tank Brigade was assembling to the north. The Panzerarmee Afrika was bottled up in the Cauldron, and since it still hadn’t blazed a western corridor out of the British minefields, supplies and water were critically low. Then, too, Rommel was going to be preoccupied with the capture of the 150th Brigade box at Sidi Muftah.

Rommel Seeks To Eliminate 150 Brigade Box

Rommel was in serious trouble, but the British did not seem to grasp what a golden opportunity they had. Above all the Germans were running out of water, a necessity in the desert. When a captured British officer came to Rommel and complained about the meager ration he and his fellow POW were issued, Rommel replied, “You are getting exactly the same ration as the Afrika Korps and myself—half a cup.”

The Panzerarmee Afrika’s situation was becoming desperate. They needed a secure and uncontested supply route—and to have that, they had to eliminate the 150th Brigade box. Rommel called for a major effort on May 31.

The 150th Brigade box was a strong one, featuring an all-arms defensive system with dug-in infantry, artillery, and armor. The garrison consisted of two battalions of Green Howards and one battalion of the East Yorkshire Regiment—tough working-class men who were inured to hardship and were stubborn, courageous fighters. There were about 80 Matilda Mk II tanks and also Matilda Mk I’s, supplemented by such formidable artillery as the new six-pounder antitank guns and 25-pounders. This was defense in depth, with tangles of barbed wire and mutually supporting fields of fire, and the entire 150th Brigade box was cocooned by belts of lethal minefields.

The commander of the Luftwaffe in the campaign, Fliegerfuhrer Afrika General von Waldau, lent Rommel what support he could. Dive bombing Stuka 87s roared in, these “birds of prey” dropping bombs on the stubborn defenders. The Panzerarmee Afrika moved forward to the attack, but the going was slow and bloody. British soldiers had always excelled in defense, and the 150th Brigade made the Germans pay dearly for every inch of desert sand.

Attack Takes Toll On British Brigade

By June 1 the 150th Brigade found its ammunition running low. The box had been well supplied with enough food, water, and ammunition to last (in theory) 21 days, but in combat conditions prodigious amounts of supplies were consumed. The 150th Brigade box became a literal hell on earth with screaming shells, mortar rounds, and bombs all tearing into sand, flesh, and blood. German corpses lay sprawled before British machine gun posts; knocked out German tanks burned fiercely and added heat to the desert inferno.

The blazing temperatures produced rivers of sweat, parched lips, and dry mouths; for the British water was becoming as scarce as ammunition. In spite of gallant resistance, the end was in sight by noon of June 1. By that time the British had only 13 serviceable tanks and all the six-pounder guns had been knocked out. The British defensive perimeter in the 150th Brigade box slowly shrunk, and as positions were overrun fighting was hand to hand with grenades and bayonets.

Germans Vulnerable, But No British Offensive

The 150th Brigade looked to General Ritchie for relief, and he responded with a barrage—of words. The commander of the Eighth Army exhorted the 150th Brigade to hold out, to persevere as British soldiers have always persevered, yet he launched no major offensive against the Germans. As indicated earlier, the British missed a great opportunity during this period. If Ritchie had ordered a major attack against Rommel May 29, 30, or even June 1, he might have dealt the Panzerarmee a major defeat.

What went wrong? General Ritchie was a competent staff officer but lacked experience in commanding whole armies. His personal style—favoring consultation and discussion with both superiors and subordinates before action—was the exact opposite of Rommel’s. When it came to major decisions only one heart and brain directed the Panzerarmee—Erwin Rommel’s. In fairness to Ritchie, other officers felt much the same as he did. For example, one British subordinate commander said he would “think about it” when advised to take another command—and such dithering is fatal in war.

Then, too, the British were partly misreading the overall situation, believing that Rommel was trapped in the Cauldron and that his attacks on the 150th Brigade box were frantic attempts to escape. Even if that were so, it is difficult to explain the British inertia. Perhaps they thought they had plenty of time to attack, or perhaps they hoped they could in essence starve Rommel out and avoid unnecessary bloodshed. The British commander in chief Middle East, General Claude Auchinleck, signaled to Ritchie that Rommel “must not get out (of the Cauldron).”

150th Brigade Falls After a Tough Fight

While Ritchie sat on his hands the end was drawing near for the 150th Brigade garrison at Sidi Muftah. Rommel personally led a platoon of panzergrenadiers to mop up the last remaining strong points. Companies “B” and “C” of the Green Howards Regiment were said to be the last fighting units in the box. The brigade commander, General Haydon, had been killed. The soldiers in Captain Bert Dennis’s platoon were the last to be overrun; all resistance at Sidi Muftah ended about 1:00 p.m. June 1. Some 3,000 prisoners were taken. Rommel hoped to liberate General Cruewell, who had been taken prisoner at the Sidi Muftah box, but was informed the general had been moved some time before. Cruewell was destined to remain in British hands.

The 150th Brigade’s valiant fight was worthy to be included in some of the British Army’s most notable exploits. It was Erwin Rommel, a chivalrous enemy, who paid tribute to the 150th Brigade by saying the Germans had to fight “against the toughest British resistance imaginable. The defense was conducted with considerable skill and, as usual, the British fought to the last round.”

Germans Focus On Taking Box At Bir Hacheim

By now supply corridors had been blazed through the minefields, and they were now secure from attack. The Italians in particular had distinguished themselves in clearing the minefields. But the colonel general had scant time to savor a local victory; he had a larger battle to win. After some consultation with Field Marshal Kesselring, Rommel decided that the southern portion of the Gazala line from Sidi Muftah to Bir Hacheim must be cleared of the British and fully secured by the Germans. To this end the box at Bir Hacheim—so long a thorn in Rommel’s side—would have to be taken as soon as possible.

Like its northern counterpart at Sidi Muftah, the Bir Hacheim box was well protected and defended by tough and determined troops. In this case, however, the troops were the 1st Free French Brigade and a Jewish volunteer battalion under General Pierre Koenig. The 3,000 Frenchmen, 1,000 men of the Jewish Battalion, and even some men from the famed Foreign Legion were in a heavily fortified stronghold covered by artillery and machine guns. It was said that Bir Hacheim had 1,200 machine gun nests capable of spewing out a rapid-fire rain of death.

The fighting at Bir Hacheim was particularly brutal, and almost as if to compensate for the French defeat in 1940, Koenig’s men refused to surrender. Water ran out, and German attacks were so heavy that no one had time to collect and bury the dead. Soon the terrible smell of putrefying corpses was added to the noise, terror, and general discomfort.

Uncoordinated British Offensive Repelled

On June 5, 1942, General Richie finally launched a major offensive against Rommel. Code named “Aberdeen,” it was a costly fiasco. It was the same old story; uncoordinated attacks with infantry unsupported by armor, armor unsupported by artillery. The British were repulsed with heavy losses. By the time “Aberdeen” sputtered to a halt the Eighth Army lost more than 150 tanks, 100 field guns and 36 antitank guns. The Indian 10th Brigade had been completely wiped out in the debacle.

Probably the worst episode of “Aberdeen” was the brave and futile attack of the 32nd Tank Brigade against the 21st Panzer at Sidra Ridge. The British went in without adequate infantry or artillery support in what would later be called “one of the most ludicrous attacks of the campaign.” The 32nd Brigade blundered into a minefield, stalled, and became a sitting duck for the German defenders. The Brigade lost 50 of its 70 tanks in this fiasco.

The fighting continued; General Ritchie gave General Koenig permission to break out of the Bir Hacheim box. On June 10 the Free French did manage to break through German lines and avoid captivity, but with the taking of the Bir Hacheim box Rommel now held the southern half of the Gazala line. Ritchie patched together another defensive line to Trigh Capuzzo, a line that paralleled the Mediterranean coast to El Adem. The Germans quickly tore a gap though this improvised new defensive line, and by nightfall June 11 the Panzers were through. The British “boxes” holding the northern end of the Gazala line faced a decision: abandon their now untenable positions and retreat eastward or face encirclement and capture.

Tobruck Captured; Rommel Makes Field Marshal

Rommel pushed on, and on June 20 Tobruck—long a symbol of British resistance in the desert campaign—was taken by the Panzerarmee Afrika. The news electrified Germany, and in recognition of his capture of Tobruck Hitler made Rommel a field marshal. At 50 the Desert Fox was the youngest field marshal in the German army. Tobruck had been taken with relative ease, in part because the defenses of the port fortress had been allowed to decay since the epic siege of 1941. Even its mines had been taken away to bolster the defenses of the Gazala line, and now it was all for nought.

The Battle of Gazala, officially fought May 26–June 22, 1942, was Rommel’s masterpiece, showing the German general at the height of his powers. He did make some mistakes, such as neglecting to take Bir Hacheim earlier in the battle. Yet when all is said and done, the British were not so much outfought as outgeneraled. The Eighth Army’s General Ritchie had been overcautious, dilatory, and too prone to waste time with endless debate and consultation. At Gazala, Erwin Rommel earned his laurels as the “Desert Fox.”

Great article on the desert fox. The battle information was outstanding. I am a WWII FAN LOVED THE BATTLE DESCRIPTIONS