By Peter Kross

The Civil War was fought out in the open on battlefields across the United States. But beginning in early 1864, the highest levels of the Confederate government decided that another, more clandestine war would be fought behind the lines in the North. Plans were put into place to set up secret operations north of the border in Canada. There, a shadowy group of secret agents, adventurers, and other Confederate sympathizers began planning a series of attacks on forts, cities, and other strategic locations in the North to wreak havoc on the Union war effort. In time the secret Canadian operation would see the arrival of John Wilkes Booth, developing his plan to either kidnap or kill President Abraham Lincoln. Booth’s accomplice John Surratt Jr., a Confederate courier, used Canada as a safe haven for his clandestine activities.

As part of the British Empire, Canada was home to a large number of Americans who had immigrated there in the years following the American Revolution. Canada was morally opposed to the idea of slavery but had many mercantile contacts with Southern planters whose cotton was imported north of the border. As the Civil War grew in intensity, members of the Canadian government took a neutral stance on the war, but a large portion of the population sympathized with the South. Canada served as the home to hundreds of Confederate prisoners of war who escaped capture. Canada also served as a secure communications link between England and the Confederacy.

Off to Canada

In 1864, the Confederates began sending agents to Canada to set up what would later become a large-scale covert network. One of the principal figures who would help establish the system was Judah Benjamin, a former United States senator from Louisiana who had served successively as Confederate attorney general, secretary of war, and secretary of state. Benjamin was one of the most important Jewish leaders of the Confederacy and was well regarded by all who knew him. Throughout this period, Benjamin was taking orders regarding the establishment of a Confederate secret service bureau from President Jefferson Davis and other top-ranking officials, including Secretary of War James Seddon and Brig. Gen. John Henry Winder, the provost marshal in Richmond. In February 1864, the Confederate Congress passed a bill establishing a secret service fund of $5 million, of which $1 million was set aside for Canadian operations. These funds were under the direct control of Benjamin, who had complete discretion as to how the money was distributed.

[text_ad]

Halifax, Nova Scotia, had a large number of former Confederate prisoners. Benjamin sent James Holcombe, a professor at the University of Virginia, to Halifax as a commissioner to represent the Confederate government. Holcombe took on the new assignment with relish. One of his primary tasks was to secure the release of the 400 Confederate soldiers who were then living in Canada. His official instructions regarding the men read in part, “You are requested to make in Canada and Nova Scotia the requisite arrangements for having passage furnished them via Halifax to Bermuda, where they will receive from Major Walker, the agent of the Department of War, the necessary aid to secure their passage home.”

Before heading to Canada, Benjamin gave Holcombe $8,000, of which $5,000 would be used for expenses with $3,000 paying Holcombe’s salary for six months. A letter of credit for an additional $25,000 was sent to Liverpool, England, to provide him with emergency funds. Like any good employee, Holcombe was told to keep his receipts and provide them to the government to be reimbursed (his traveling expenses were to come out of his own pocket). He was also instructed to tell the British authorities in Canada what he was doing. The Confederates wanted to keep the British apprised of what they were doing to prevent their agents from being deported. Holcombe arrived in Halifax in March and soon discovered that there were only 12 former Confederate prisoners still living there, of whom nine were to leave that very day. He later found that there were only 100 Confederates in the entire country waiting to get home.

Robert Coxe & John Wilkes Booth

The U.S. Consul’s office in Halifax was monitoring all the comings and goings of suspected Confederate sympathizers, and in February 1864 Federal authorities noted the arrival in the city of Beverly Tucker, who formerly had served as the U.S. consul in Liverpool. While in Europe, Tucker had become an agent for the Confederacy. His job in Canada was to gather supplies for the Confederate Army. Tucker met with Holcombe and former Alabama Senator Clement Clay, who was one of the assistant Confederate commissioners sent to Canada. On March 23, President Davis authorized payment of $46,512 in secret service gold to a “Mr. Tucker.” The Tucker mentioned in the note was probably Beverly Tucker, but it could have been a man named Joseph Tucker, who had proposed working for the Confederacy as a secret agent.

Tucker was acquainted with a Confederate courier named Robert Coxe. Coxe had arrived from England in August 1862 and moved to St. Catharines, Ontario, near the New York border. St. Catharines was near Niagara Falls and strategically located on the railroad line to Buffalo. A surprising number of Northerners in the region were allied with the Confederacy, and the railroad line connected them with each other. Coxe’s job was to serve as a conduit to other Confederate agents making their way to Canada. John Wilkes Booth, the future assassin of Abraham Lincoln, had his own longstanding ties to the Confederate government. In October 1864, Coxe was in Poughkeepsie, New York, before leaving for Canada. At the same time that Coxe was in that city, Booth was supposed to have been in nearby Newburgh, 14 miles away. It is possible, given Booth’s secret affiliations with the Confederates, that he and Coxe met to discuss business. One day later Booth went to Montreal, where he had meetings with various other Confederate agents.

With more and more Confederate agents filtering into Canada, the leadership of the Confederate government decided that it was time to send an official delegation to Canada to set up a spy mission directed against the North. Alexander Stuart, a former member of Congress who had been U.S. secretary of the interior from 1850 to 1853, was asked to serve as their official commissioner. Stuart arrived in Richmond for talks with Jefferson Davis and Judah Benjamin, who told him that the Confederacy had decided to mount an official espionage effort in Canada and that he was just the man to lead the effort. They told Stuart the Confederate government had deposited a sum of three million pounds in a London bank to fund the effort. To their chagrin and surprise, Stuart turned them down. He would not betray the U.S. government.

Setting Up Home Base in Montreal

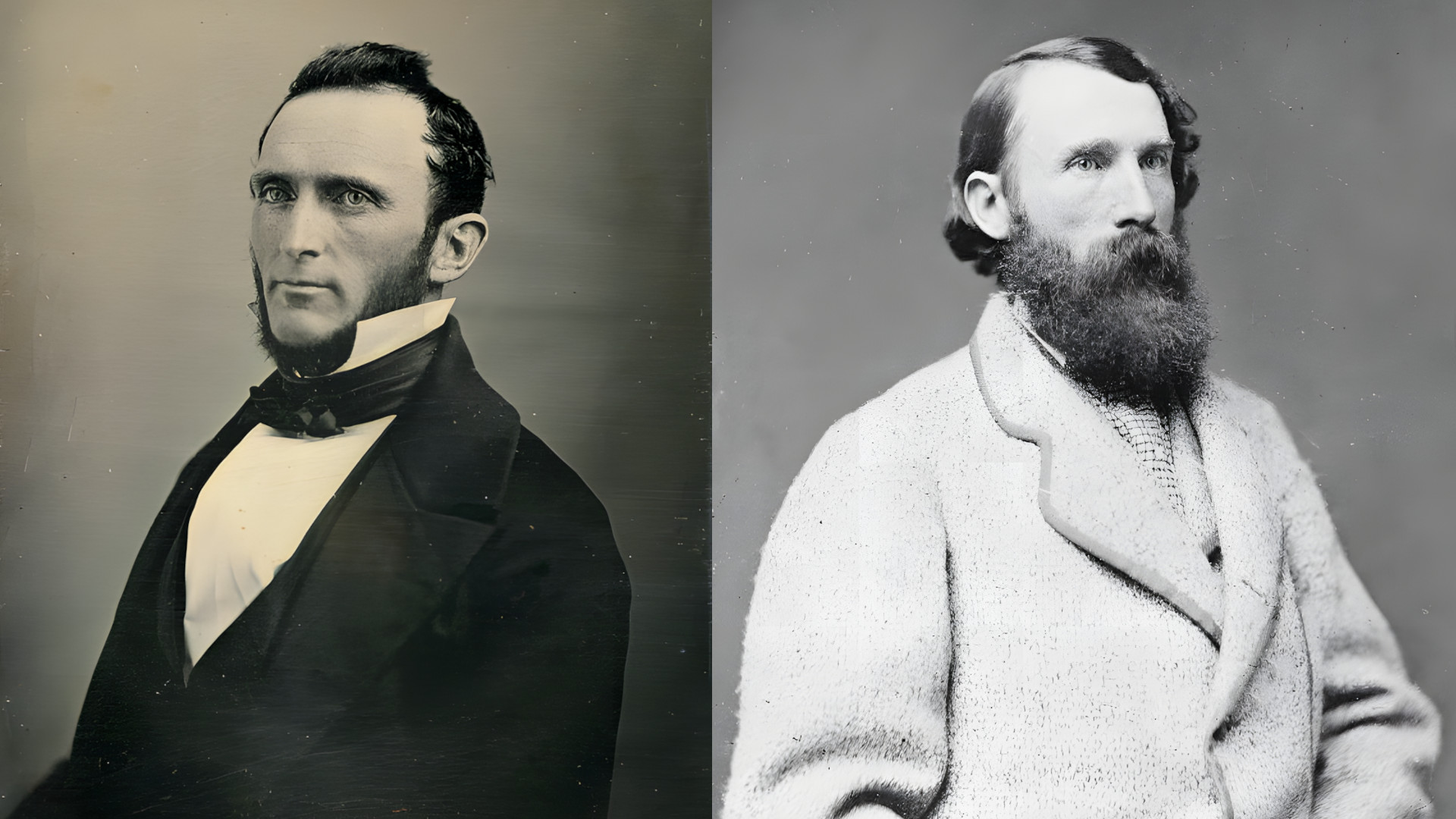

Davis and Benjamin had better luck with their next candidate, Jacob Thompson. Like Stuart, Thompson had a fine pedigree in politics, having served as a congressman and secretary of the interior under President James Buchanan. Being from Mississippi, Thompson had no love for the Union and accepted the job at once. Thompson was to serve as the head of the Confederacy’s underground movement in Canada and had the final say in what operations he wanted to conduct and the people he would hire. Using Canada as his base of operations, Thompson was directed to wreak havoc on Union targets and disrupt the Federal war effort. He was to use his assets to attack Union military facilities in the Northwestern states and foment rebellion. If these efforts were successful, said Davis, then Abraham Lincoln would have no choice but to sue for peace on Richmond’s terms. Davis gave Thompson a draft for $l million in gold to finance the operation and told him to “carry out such instructions as you have received from me verbally.”

Thompson was the senior official, and Clement Clay was his second in command. One of Clay’s responsibilities was to work with the Copperhead movement in the North. The Copperheads were Northern Democrats who opposed Lincoln’s administration and wanted to see a negotiated end to the war. The Copperhead movement included such fringe groups as the Kings of the Golden Circle and the Order of the American Knights, neither of which had much influence on the war effort. Even though Clay was a commissioner, he worked for the Confederate War Department and received all his funds from that office.

Thompson and Clay arrived in Halifax from Richmond on May 19. They soon left for Montreal, which they would make their home base. At that time, Montreal was known as the spy capital of the north, with secret agents from both sides taking up residence there. All sorts of shady character flocked to Montreal. Some of the Southern men were revolutionaries; some were simply out for adventure.

Unfortunately for the Confederates, Thompson and Clay soon developed a deep hatred for each other. Sickly and ill-tempered, Clay had little interest in playing second fiddle to Thompson. The two men separated soon after arriving in Canada. Thompson settled in Montreal, while Clay moved to St. Catharines. Their military adviser, Captain Thomas Henry Hines, later described the clash of personalities. “The commissioners were not harmonious from the inception of their mission,” Hines wrote in Southern Bivouac magazine in 1886. “This was a source of constant embarrassment and proved one of the most potent obstacles for success. They found it impossible to agree. Colonel Thompson was a man of sterling integrity, but he was inclined to believe too much that was told to him, to trust too many men, to doubt too little and suspect less. His subordinates were kept in continual apprehension, lest he compromise their efforts by indiscreet confidences.” Hines’ associate, Captain John Castleman, liked Thompson, but found Clay “not practical. He lacked judgment. He was peevish, irritable and suspicious. He distrusted Mr. Thompson and relied on those who were often untrustworthy.”

Also arriving in Montreal was William Cleary, who served as Thompson’s private secretary. When Cleary arrived in Canada he was wanted by Federal authorities for some unknown reason. As Thompson’s private secretary, Cleary knew all about the clandestine goings-on in Canada, and he played an integral role in sabotage efforts against the Union. One involved a transplanted Kentucky physician named Luke Blackburn, who had gone to Canada at the behest of Mississippi Governor John J. Pettus to oversee relief supplies arriving aboard blockade runners from England. Blackburn, a relative of Kentucky Senator Henry Clay, had helped fight yellow fever outbreaks in the South and, most recently, in Bermuda. According to testimony revealed in his subsequent trial, Blackburn put that experience to work in a less benign way, attempting to spread the dread disease among the military and civilian populations of the North. He supposedly sent clothing believed to be infected with yellow fever to Abraham Lincoln as a gift. He did not want to deliver the package himself and asked that a friend deliver it for him. At the last minute, the man refused to make the delivery. At the time it was believed that yellow fever was spread by human contact, although it is actually spread by mosquitoes.

The Northwest Conspiracy

The commissioners in Canada turned their attention to what would become known as the Northwest Conspiracy. Working with the Order of the American Knights, their plan was to take the war to the states on the Canadian-American border, particularly Ohio. The man the Confederates tasked with the job was Hines, who had served in the 9th Kentucky Cavalry Regiment under Brig. Gen. John Hunt Morgan. Both Morgan and Hines were captured in a cavalry raid into Ohio and were put in prison in the Ohio Penitentiary. They soon escaped, and Hines made his way to Canada after a trip to Richmond, where he got his instructions from the Confederate leaders. Once in Canada, Hines worked with the Knights to bring the war to the Northern states. Hines worked directly with the Confederate State Department, but he got his instructions in secret code from the Confederate Signal Corps. Hines was given $5,000 and a supply of cotton to sell to finance his operations. Hines and his men supplied the Knights with guns and ammunition, but a Federal agent inside their organization leaked the information, and the plot was uncovered.

In August 1864, the Confederates sent 62 men from Canada to Chicago with the purpose of freeing prisoners of war at Camp Douglas. Hines met with Clement Vallandigham, the North’s most prominent Copperhead, to discuss details of the raid. Vallandigham promised to arm and send 100,000 men into the streets of Chicago to support the invasion. The revolt was timed to coincide with the Democratic National Convention, which was also taking place in the city. At the last minute, however, Vallandigham and the other Copperheads backed out, perhaps thinking the Democratic presidential nominee, General George B. McClellan, would defeat Lincoln anyway and bring a negotiated end to the war. A disgusted Hines later scoffed, “There was a reluctance on their part to sacrifice life to a cause.”

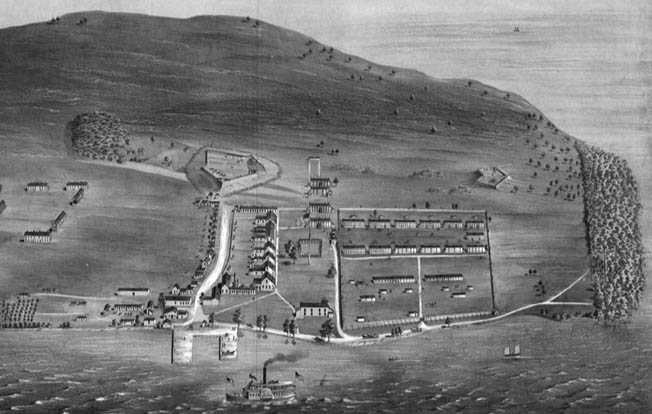

Another operation carried out of Canada was undertaken with Thompson’s cooperation. The plan called for the capture of the steamer USS Michigan, which was operating on Lake Erie, and use it to free the estimated 2,700 Confederate prisoners held in a Union prison camp at Johnson’s Island in Sandusky, Ohio. The escaped prisoners would then band together as a foraging army and fight their way back across the state to Virginia, while the Rebel-controlled Michigan would move down the lake, bombarding Detroit, Cleveland, Buffalo, and Sandusky, Ohio. The man whom Thompson asked to head the operation was John Yates Beall, a well-known Confederate sailor who went by the nickname “Mosby of the Chesapeake,” due to his successful exploits against Union shipping on that river. On September 19, Beall destroyed four Union schooners. Elaborate plans had been set up to carry out the raid. Beall and 20 men boarded the ship Philo Parsons, which ran on the Detroit-Sandusky route. Beall asked the skipper to make an unscheduled stop at Amherstburg on the Canadian side of the border, where he picked up more men.

The Conspirators Get to Work

As the ship got closer to Johnson’s Island, Beall took over the vessel and hoisted the Confederate flag. He let the passengers out before heading for his destination. Captain Charles Cole of the Confederate Army was to signal from shore that it was all clear to attack the fort. However, Cole was arrested by Federal authorities. It was later speculated that Cole had been betrayed by a Confederate captive held aboard Michigan. With no signal at hand, Beall broke off the strike and returned to Canada. Cole was taken to Fort Lafayette in New York harbor, where he was tried and convicted of spying for the Confederacy. A full confession earned him amnesty, and Cole was released in the spring of 1865. He drifted to Mexico after his release and eventually went into the postwar railroad business in Texas.

Beall’s next assignment was to intercept a train carrying seven Confederate general officers from Johnson’s Island to Fort Lafayette. The raid was a failure, and Beall was captured. He was put on trial, found guilty, and was sentenced to hang. Beall, made of sterner stuff than Cole, refused to confess, and Federal authorities carried out his execution on February 24, 1865. There was a tenuous link between John Wilkes Booth and John Yates Beall. Both men had been present at the hanging of John Brown, the abolitionist hero, in 1859. Whether or not they met on that occasion is unknown.

Another operation funded by the Canadian commissioners was a plot to set fires in certain hotels in New York City in 1864. The saboteurs were to use Greek fire, an incendiary substance made from an unstable mixture of pine resin, naphtha, quicklime, calcium phosphide, sulfur and niter, to attack hotels that were packed with guests. The agents managed in the end to set fire to 19 hotels, a theater, and P.T. Barnum’s American Museum, but the fires did not do as much damage as expected, and the panic they hoped to spread among the city’s population did not materialize.

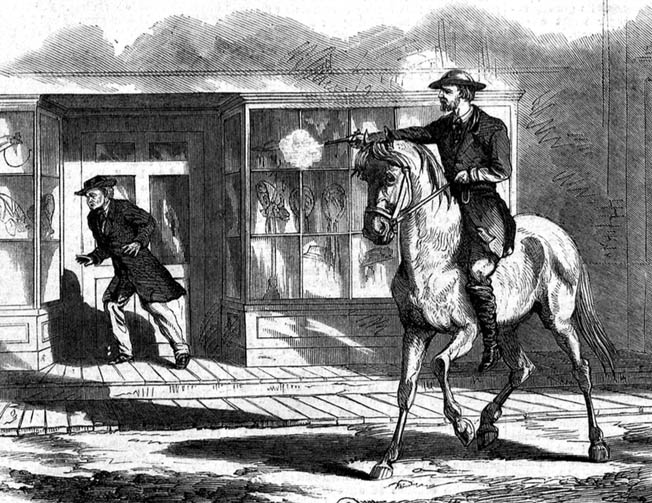

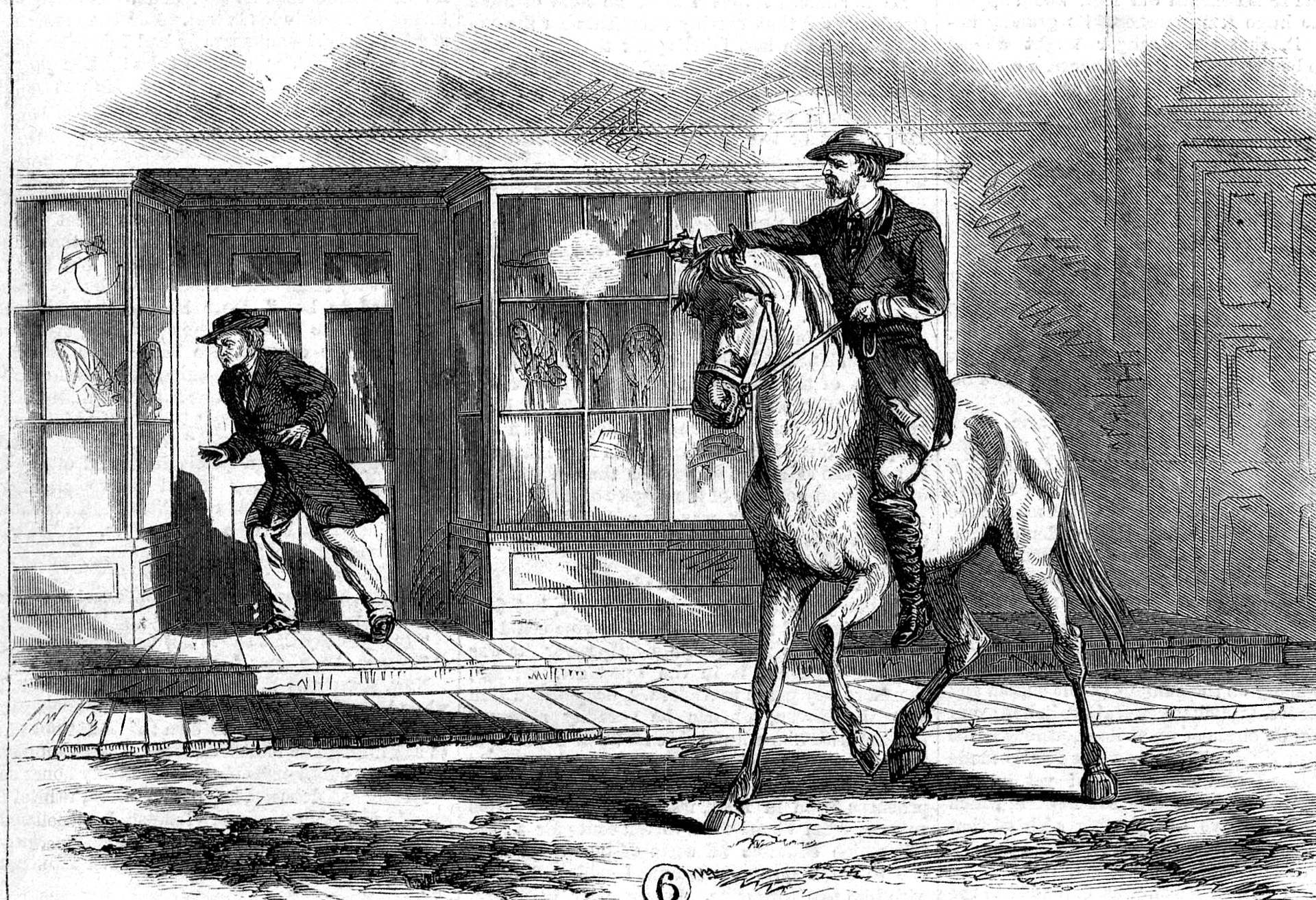

Despite the failure of the New York operation, the Confederates in Canada had more plans up their sleeves. The most successful operation called for robbing three banks and burning the town of St. Albans, Vermont, only 15 miles from the Canadian border. The plan, the brainchild of Confederate Secretary of War Seddon, was supervised by Lieutenant Bennett Young, who had served as an officer under the command of cavalry leader John Hunt Morgan. Young had been captured during a raid in Ohio in 1863 but escaped from Camp Douglas in Chicago and fled to Canada. He had good reason to seek revenge.

The purpose of the raid was to use the stolen money from the St. Albans banks to fund future Confederate operations and create panic in Northern states. Young and two of his men arrived in St. Albans on October 10, 1864, to learn the habits of the residents of the town and blend in as best they could. Over the next several days, 20 more of Young’s men arrived. When asked by the locals why they were in town, they said that they were Canadian sportsmen on a hunting and fishing trip. The men carried Greek fire to burn down the town. On the morning of October 19, the raiders strode into the middle of St. Albans, gathered up the townsfolk, and put them in a safe place. Then they entered the Franklin County Bank and took what was described as “a considerable amount of cash” and locked up two cashiers in the vault. After that they raided the St. Albans Bank, where they took off with the silver but left the gold after the teller told them that there was no gold in the bank. The raid netted Young and his men a total of $200,000.

The Canadian Spy Ring in Disarray

Before leaving town, the raiders unsuccessfully tried to burn down some municipal buildings. Townsfolk decided to fight back, and a shootout took place in which one resident was killed. Local residents managed to locate Young and took him into custody near the Canadian border. However, a British officer persuaded the citizens to release him into his custody. When the dust settled, 14 of Young’s men were arrested in Canada and $90,000 was recovered. The raiders were sent to Montreal to face trial. An unapologetic Young wrote of the St. Albans raid: “I went to St. Albans for the purpose of burning the town and surrounding village as retaliation for recent outrages in the Shenandoah Valley and elsewhere in the Confederates States.”

The Lincoln administration tried all sorts of diplomatic strategies to have the men sent back to the United States for trial but was unsuccessful. Young and his men were put on trial in Canada, where a judge ruled that their actions were legitimate acts of war and set them free. The Canadian government did, however, return $88,000 to the St. Albans banks that had been robbed. If nothing else, the raid at St. Albans brought the war to the very border of Canada, even though it did not alter the outcome.

By December 1864, it had become obvious to Confederate authorities that the Canadian spy ring led by Thompson and Clay had fallen into disarray. Thompson was simply too trusting to be an effective spymaster. Traitors and double agents were everywhere, and Federal detectives staked out the bar in his Toronto hotel and the railway station across the street, logging all suspicious comings and goings. “I had hoped to have accomplished more,” Thompson wrote in a letter to Confederate leaders on December 3. “But the bane and curse of this country is the surveillance under which we act. Detectives, or those ready to give information, stand on every corner.”

Double Agents in Their Midst

By far the most damaging double agent was Arkansas native Godfrey Joseph Hyams, who had relocated to Toronto with his wife in late 1863. Hyams was eking out a living repairing shoes when Thompson gave him $50 to help in a mission—mainly out of the goodness of his heart. Hyams repaid Thompson’s kindness by going straight to Robert Harrison, Toronto’s crown attorney, with damaging evidence on various Confederate plots, including a second attempt to free prisoners at Johnson’s Island by capturing a second steamer, Georgian, and transporting the men to safety. Armed with Hyams’ testimony, Canadian officials impounded the vessel at Collingwood on Lake Huron, ending the rescue effort.

Hyams’ most damaging testimony concerned a secret arms factory that Thompson allegedly was operating in a Toronto house, making torpedoes, hand grenades, and Greek fire. As reported by U.S. Consul David Thurston, “The house Hyams described was empty, but his belief was that certain of these incendiaries were buried under the floor. Two policemen were detailed to examine the premises and in the extremity of the hall a portion of the floor was removed and under four inches of water and 18 inches of earth, several torpedoes were found buried. These torpedoes are covered with a mixture of broken coal and pitch and resemble pieces of bituminous coal. They are made of cast iron of irregular shape, hollow and are filled with power and covered. Hyams says they are to be thrown into coal bins in factories and steamboats, etc., where they will, without being noticed, be shoveled into the fire and effect the purpose for which they are designed.”

Crown Attorney Harrison told Thurston that he hoped to arrest Thompson for conspiring to violate Canada’s neutrality laws. Before that could happen, Confederate authorities pulled the plug on the entire operation. Clay had already returned to the South, and on December 30, Secretary of State Benjamin ordered Thompson home as well. “From reports which reach us from trustworthy sources,” said Benjamin, “we are satisfied that so close an espionage is kept upon you that your services have been deprived of the value which is attached to your residence in Canada. The President thinks it is better that you return to the Confederacy.” Thompson eventually sailed to England before he could be charged, living in exile for two years before returning to the United States and settling in Memphis. He was never prosecuted for his alleged spying activities.

Booth in Montreal

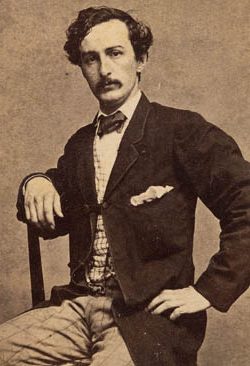

The final piece of the puzzle of the Confederates’ Canadian operation was the presence in Montreal of Lincoln assassin John Wilkes Booth in the months leading up to the president’s murder. Booth was an ardent Southern sympathizer but did not join the Confederate Army once the war started. Instead, he decided to use his fame as one of the nation’s premier actors to further the Confederate cause in his own way. During the war Booth was a low-level courier for the Confederates and smuggled medicine to the South, doing a little spying along the way. Booth’s sister, Asia Booth Clarke, in a tell-all book she titled the Unlocked Book, wrote, “I now knew that my hero was a spy, a blockade-runner, a rebel. I set these terrible words before my eyes and knew that each one meant death.”

During the war, Booth traveled to such places as Baltimore, Philadelphia, New York, and Montreal, meeting with Confederate agents. What is not in doubt is that Booth had meetings with certain members of the Confederate Secret Service in Montreal during the war. Booth met with Patrick Martin, who was part of Thompson’s spy ring. Martin gave Booth letters of introduction to Dr. Samuel Mudd of Bryantown, Maryland, who later set Booth’s broken leg at his home after the actor killed Lincoln.

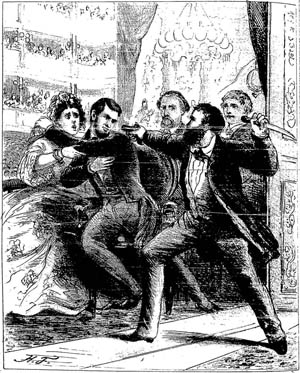

Booth arrived in Canada on October 18, 1864, and registered at the St. Lawrence Hall Hotel, a hotbed of Confederate Canadian operations. Booth had various meetings with Patrick Martin and George Sanders, who was a believer in political assassination. It is not out of the realm of possibility that Confederate plots to either capture or kill the president were discussed. While in Montreal, Booth was able to use money deposited for him in the Ontario Bank in the amount of Canadian $455. This money was most likely supplied to Booth by the Confederate commissioners living in the city. Immediately after leaving Canada, Booth came to Washington, where he took a room at the National Hotel and made deposits in a bank owned by Jay Cooke.

History in the Shadows

A check was written on November 16, 1864, on the account of Jay Cooke and Co., at a bank in Washington in the amount of $100. It was payable to a Matthew Canning, a longtime friend and theatrical agent of Booth’s. A total of seven checks were drawn on the account—$100 to Canning, a $150 check cashed by Booth on January 7, 1865, and another one for $25 that was also cashed by Booth on March 16. What makes these transactions interesting is that Booth had made deposits in Cooke’s bank just after he made his covert trip to Montreal. When Booth was killed at Garrett’s farm, soldiers found a Canadian bill of exchange on his body. This paper trail has been cited by researchers attempting to tie Booth to the covert activities of the Confederate Secret Service and its relationship to the assassination of the president. When Federal detectives searched the room of George Atzerodt, one of Booth’s accomplices in the plot to kill the president, they found Booth’s bank book with the $455 amount duly recorded.

Another accomplice of John Wilkes Booth in the Canadian operation was John Surratt Jr., whose mother, Mary, owned the boarding house in Washington where Booth and his accomplices met to plan the president’s capture/murder. Surratt was a Confederate courier and a friend of Booth’s. After the president’s assassination, Surratt fled to Canada, where he was given sanctuary by Catholic priests before making his way to England, Italy, and Egypt, where he was captured and sent back to the United States to stand trial in the president’s murder. Young Surratt faced the same charges as that of his doomed mother, Mary, but the jury failed to reach a verdict and he was set free.

Another accomplice of John Wilkes Booth in the Canadian operation was John Surratt Jr., whose mother, Mary, owned the boarding house in Washington where Booth and his accomplices met to plan the president’s capture/murder. Surratt was a Confederate courier and a friend of Booth’s. After the president’s assassination, Surratt fled to Canada, where he was given sanctuary by Catholic priests before making his way to England, Italy, and Egypt, where he was captured and sent back to the United States to stand trial in the president’s murder. Young Surratt faced the same charges as that of his doomed mother, Mary, but the jury failed to reach a verdict and he was set free.

No positive link to the Lincoln assassination and the Confederate spymasters in Canada has ever been made. Like so much else surrounding the controversial mission, the facts remain in the shadows. The Confederate operations in Montreal and other Canadian cities were merely a sideshow to the savage land battles being fought in the United States. But the operations had the blessing and authorship of the highest levels of the Confederate government in Richmond. Perhaps they gave their blessing to Booth as well. If so, the evidence remains to be seen.

“There, a shadowy group of secret agents, adventurers, and other Confederate sympathizers began planning a series of attacks on forts, cities, and other strategic locations in the North…”

would the word “terrorists” better describe these people than “adventurers” .

The term adventurers seems to imply something less than commitment to the cause, which is probably correct. Also, this was part of a “declared war,” so perhaps “enemy combatants” is a better description than terrorists.