By Michael D. Hull

One of America’s earliest heroes in World War II was the tall, soft-spoken son of a Connecticut Congregational minister who distinguished himself in some of the fiercest fighting in the South Pacific.

Evans Fordyce Carlson was a professional soldier of legendary courage in the U.S. Marine Corps tradition of Dan Daly, David Shoup, and Chesty Puller, and he was as heroic in his opinions as in his actions. He had definite ideas about how to fight wars and how to maintain peace, and his need to speak out probably shortened a brilliant career.

He established a spectacular reputation as the commanding officer of the 2nd Marine Raider Battalion which raided Makin Island on August 17, 1942, as a diversionary action during the early days of the Guadalcanal campaign, and destroyed the Japanese garrison. He later was decorated for distinguished leadership at Guadalcanal, Tarawa, and Saipan, yet after 1943 was relieved of active command and relegated to staff duties.

Not a Military Virtue

Carlson was a victim of the military establishment that recoils from soldiers who speak their minds, no matter how bright their combat records. He had spent several years before the war as a military observer in China and had irked some authorities in the United States by praising the fighting qualities of the Chinese Communists struggling against the Japanese invaders.

He was opposed to supporting Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek—calling him a “betrayer and compromiser”—and was subsequently branded as a leftist in certain quarters. Carlson was a strong believer in comradeship between officers and men, and maintained that the paternalistic caste system had no place in the armed forces of a democracy.

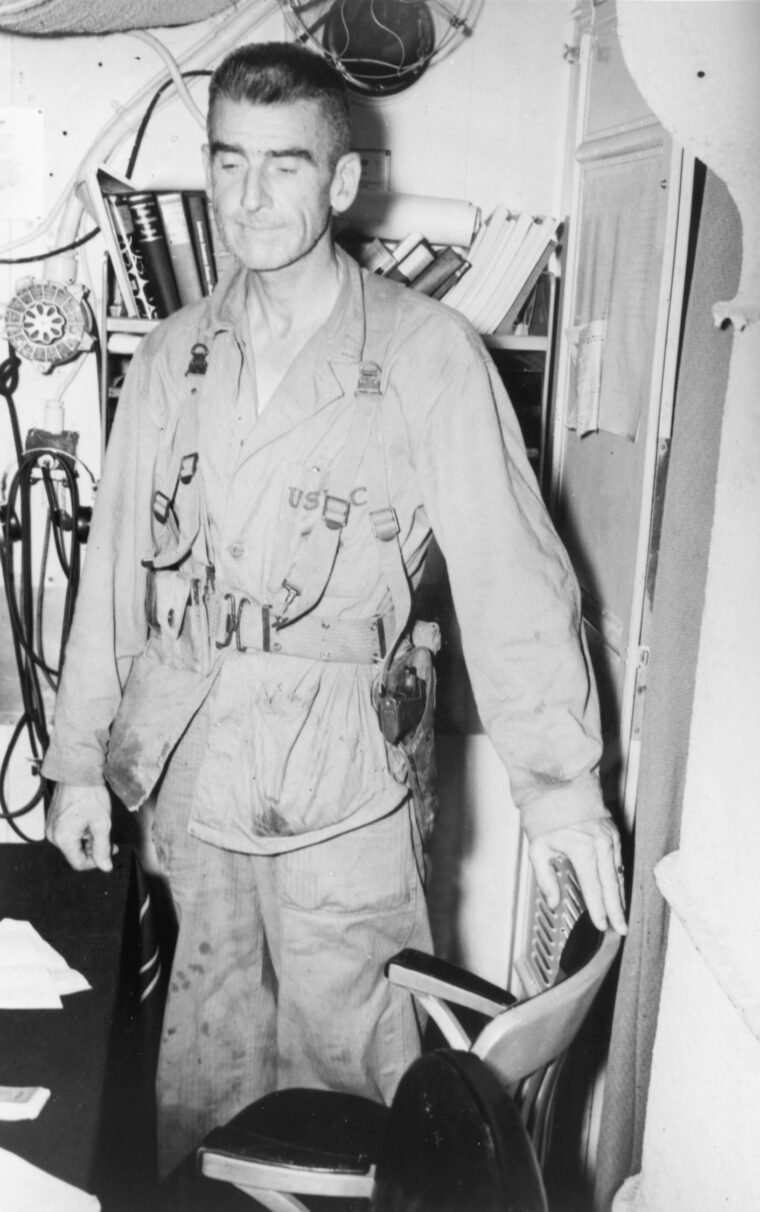

Carlson was both a man of action and a man of reason. His habits and needs were simple. Six feet tall, fair, and weighing about 165 pounds, he had a “long, solemn face and a keen eye.” He was friendly and sympathetic, and his bearing was more that of a Westerner than a soldier. Rangy and somewhat gaunt, his appearance was somewhere between that of Abraham Lincoln and Gary Cooper.

Whether leading his Marines behind the enemy lines on Guadalcanal or relaxing at home in the peaceful Connecticut town of Plymouth, Carlson displayed genuine concern for his fellow man. “He was a warm man and had a great sense of humor,” recalled his next-door neighbor, Mrs. Lewis Mattoon. “He loved to sit and talk, he was friendly, and he would be the first to help anyone.”

An Officer and a Gentleman

The Reverend Thomas Carlson was pastor of Plymouth Congregational Church for 25 years, and his son loved to return there between campaigns. “He enjoyed gardening, picnics, outings, and going to the post office to collect the mail,” said Mrs. Mattoon. “The only relaxation he had was in Plymouth … He made piles of leaves for my daughter to play in in the fall, and he was just as regular as could be. He always had a smile.”

The Mattoons and the Carlsons were close families, and Carlson would bring gifts of shoe skis from China and perfume from Hawaii for the Mattoons’ daughter, Marilyn. “Carlson was an officer and a gentleman,” said Mrs. Mattoon. “He never blew his own horn, and when complimented for anything he would always give credit to others.”

While staying at his parents’ parsonage facing the town green in Plymouth, Carlson liked to retreat to a second-floor room with windows facing the scenic western Connecticut hills. There, he wrote two books, Twin Stars of China and The Chinese Army, and a host of magazine articles.

16, Going on 22

Evans Carlson was born on February 26, 1896, in Sydney, NY. At the age of 14, he left home to work on a farm near Vergennes, Vt., and attended the local high school. But he was not much interested in books, and the following year he left school to work as an assistant freight master in the New Haven, Conn., railroad yards. A year later, he worked as a chainman in New Jersey, and, still restless, walked into an Army recruiting office on Election Day, 1912, and said he wanted to join the U.S. Cavalry.

Evans, then 16 years old, lied about his age because the Army’s minimum was 21. He said he was 22. The recruiter was a field artillery sergeant, and he managed to sign up the lad for his own branch of the service.

After three months of basic training on Long Island, young Evans was shipped to the Philippines, where he watched the construction of the fortress of Corregidor. He also served in Hawaii, and was discharged in 1915 as a top sergeant with “high commendation.” He tried his hand at well-digging and surveying in California, but was recalled into service during the 1916 border trouble with Mexico. He was sent to Texas to train reserve officers from colleges and was commissioned a second lieutenant when the United States entered World War I.

Carlson went to France in 1918 as a captain commanding a headquarters company of the 87th Infantry Division, and was cited for his work by General John J. Pershing, supreme commander of the American Expeditionary Force, and by the governments of France and Italy. He was the first U.S. soldier sent into Koblenz, Germany, as a member of the occupation army.

Carlson was discharged with the rank of captain at the age of 23. Again he tried civilian life, working for two years with a canning company, but “the urge to the service was too strong.” He enlisted in the U.S. Marine Corps as a private in 1922, and the following year he was commissioned a second lieutenant. After soldiering at Quantico, Va., in Cuba, and on the West Coast, he applied for aviation training. He was sent to Pensacola, Fla., but did not complete his training and returned to line duty four months later. He advanced rapidly and distinguished himself wherever he was sent.

Two Years with Chinese Guerrillas, Subsisting on a Handful of Rice a Day

From 1927 to 1929, he served as a regimental operations and intelligence officer in Shanghai, China, and was awarded the Marine Corps Expeditionary Service Medal. In 1930, he served as an officer in the Guardia Nacional in Nicaragua when the U.S. Marines were helping organize the country’s national guard. A first lieutenant now, Carlson was awarded the Navy Cross for “extraordinary heroism.” With 12 men, he responded to a call that a hundred bandits were looting a nearby town. Carlson and his men chased them, recovered the stolen property, and dispersed the bandits, killing two and wounding seven. The Leathernecks suffered no losses.

Carlson was commended in 1931 for his organizational work following the Managua earthquake, and the grateful Nicaraguan government gave him several decorations for his efforts in that country. Two years later, Carlson was on his way back to duties in Shanghai and Peiping (now Beijing).

Then followed two years’ duty in the United States, after which he was shuttling back to China again—to Peiping in 1937 to study the Chinese language and to act as assistant naval attaché. Now a captain and military observer at the beginning of China’s long war with Japan, Evans Carlson began a 2,000-mile journey through the regions where the Chinese Communist 8th Route Army was fighting the enemy.

With a haversack slung over his square shoulders, Carlson set out on foot to study the “pattern of resistance” the Chinese were taking in the face of the invaders. Carlson was the first American officer to accompany a Chinese ground force in a campaign. He stayed with the guerrillas for two years, marching as far as 60 miles a day and once tramping 43 miles across eight mountains in 20 hours. Like the guerrillas, he seldom ate more than a handful of rice a day.

The Secret to Enduring Hardship

Carlson learned the basic principles of guerrilla warfare thoroughly, and came to understand the reason why men could endure such hardships: “They knew what they were fighting for.” Returning from the trip, Carlson was greeted by U.S. Navy censors who toned down his praise for the Communist soldiers. Angrily, he resigned his commission and returned to the United States. He visited China again in 1940 and 1941, primarily to observe the country’s cooperatives. He wrote and lectured about the Japanese menace and about the need for China to remain united. On his way home early in 1941, Carlson stopped in Manila to warn General Douglas A. MacArthur that the Japanese would attack American installations in the Pacific. His warning went unheeded.

Carlson conceived the idea of an American guerrilla force, and in April 1941, he applied for recommissioning. He was commissioned a major and ordered to active duty that May. Carlson pressed for raider training for U.S. Marines, and this was eventually started early in 1942. Two battalions were formed, the lst under Col. Merritt A. Edson and the 2nd under Carlson. Carlson’s executive officer was President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s son, James.

The actual organization of the unit was completed in February 1942. Lt. Col. Carlson and Major Roosevelt hand-picked the Raiders. The majority of the officers were reservists “specially selected for their spirit, initiative, and democratic outlook.” The enlisted men had volunteered for both the Marine Corps and the Raider units. Carlson picked them chiefly from states where outdoor life predominates; many were from Texas, Oklahoma, Arizona, and New Mexico. Several had been soldiers of fortune in Latin America.

Fight Without Mercy… Expect No Quarter

Before accepting the volunteers for Raider training, Carlson gave each man what he termed a “psychological breakdown.” He told them graphically of the dangers, hardship, and brutalities they could expect, and told them what war with the Japanese meant. Japanese brutality, he said, had hardened the Chinese and united their leadership. He told his volunteers that they would have to fight without mercy and expect no quarter. If they still wanted to be Raiders, he accepted them.

At the San Diego, Calif., Marine Corps depot, Carlson began to train his battalion intensively. He taught the men to march 40 miles a day with full equipment, and to fight without mercy. They were expert swimmers and woodsmen, and their weapons were automatic rifles, submachine guns, semi-automatic Garand rifles, and pistols. Only men who stayed in top physical and mental condition stayed in the Raiders. British Commandos taught them how to fight with knives, and Free French Commandos showed them how to fight with their feet.

Carlson abolished officers’ privileges and the officers’ mess. All wore the same uniforms, carried the same equipment, and lived alike. The commander insisted that discipline be “firm but informal, based on knowledge, reason, and individual volition.” Carlson borrowed the Chinese 8th Route Army’s motto of “Kung-ho” (work together), and encouraged meetings to thrash out problems. The men listened to talks on democracy, freedom of speech, religion, and other democratic values. This was part of Carlson’s doctrine that men fought more effectively when they knew what they were fighting for.

A Tall, Lincolnesque Man Who Always Carried a .45

The meetings featured entertainment and group singing, as Carlson strove to weld the Raiders into a tight, cohesive unit—a family of fighting men. The men composed their own march, “Carlson’s Raiders,” sung to the tune of “Ivan Skavinsky Skivar,” and some other “lustily ribald” songs. Carlson called his unit the Kung-ho (or Gung-ho) Battalion rather than Carlson’s Raiders. He encouraged the men to write, paint, or compose if they wished, and he made himself available to all of them. He listened to their problems and understood them. He planned open discussions before every maneuver or action, and self-criticism afterward. Morale was high, and the battalion was to record only one case of battle neurosis. The Raiders loved their commanding officer.

“He was a man’s man,” recalled James E. O’Brien of East Hartford, Conn., who served in Company D of the 2nd Raider Battalion. “We underwent severe training so that we would be well suited for combat. He was a tall, Lincolnesque man who always carried a .45. He was tough but fair.” Carlson’s men believed they were an elite unit, and they itched for action. It was not long in coming.

Two companies of Marine Raiders sailed from Pearl Harbor in the late spring of 1942 aboard the cruiser USS St. Louis. She had distinguished herself as the only American ship to make the open sea during the Pearl Harbor raid on December 7, 1941. The St. Louis headed for the two tiny islands, Sand and Eastern, that make up Midway Atoll. “We didn’t know what was up,” said O’Brien.

Bombings and Beer Cans

On the harrowing, crucial days of June 4-6, 1942, companies C and D were dug in on the sparse, treeless Eastern Island. “They blasted us for five hours on the 4th,” reported O’Brien, “and on the 5th we heard noises out to sea (American planes attacking the Japanese carriers). We set barbed wire in the water and organized our primitive defenses. We had broken the Japanese code, and we were expecting an invasion by 60,000 Japs. There were about 900 of us altogether—the two companies and soldiers and mechanics—and we lay all night awaiting an invasion.”

The next day, B-25 bombers landed and were refueled by hand, and then more supplies and B-17 bombers came in. The enemy bombed Midway, but they avoided hitting the runway because they hoped to use it. Instead, they bombed the PX on Sand Island. “It was funny,” recalled O’Brien, “to see beer cans flying all over the place during the attack, and Marines scrambling to retrieve them.”

The invasion never came, after gallant U.S. Navy pilots had left four Japanese flattops burning. The battered American Pacific Fleet had managed to halt Japanese naval expansion in the Pacific and turn the tide of war in the Far East.

So the two companies of Raiders sailed back to Pearl Harbor aboard two pleasure boats. They had lost no men in their first taste of combat. Carlson’s four companies then underwent training at Pearl Harbor for their next action, a raid on Makin Island in the Gilberts as a diversionary operation during the early days of the coming Guadalcanal invasion.

The Raiders learned to use rubber boats and were introduced to the two big mine-laying submarines, the USSArgonaut and USSNautilus, that were to carry them to Makin. They trained on Hawaii’s Kaneohe Mountain and lived in pup tents. Companies C and D had been under fire at Midway, so Carlson picked Companies A and B for the raid because he wanted all his men to have tasted combat.

Four-Minute Inferno: All the Enemy Were Killed

Companies A and B crowded aboard the two submarines and headed for the British-mandated Gilbert Islands. They arrived off Makin just before midnight on Sunday, August 16, 1942. In the early hours of the next morning, the Marine Raiders disembarked in powered rubber boats and landed safely. Colonel Carlson was in the first boat to land.

The Japanese defenders fought fiercely along the coastal road when they spotted the invading Leathernecks, and at daylight, theNautilus, firing blind, sank a Japanese merchant ship and a patrol craft in the lagoon. The invaders were bombed and strafed several times by enemy sea planes, and when two sea planes sat down in the lagoon to offload reinforcements for the 70-man Japanese garrison, the Leathernecks sank them with antitank fire.

After manning defensive positions, Carlson’s 222 Leathernecks began to spread out and reconnoiter the island. They met a group of friendly natives who told them where the Japanese were, and an advance party moved cautiously along a straight dirt road running the length of the small island to make contact.

The Marines advanced along the road and then saw a unit of Japanese soldiers in green uniforms creeping through trees and brush between the road and the lagoon. The Americans double-timed to get ahead of them and then lay in ambush. The Japanese advanced aggressively, and the Marines, some of whom were carrying shotguns, unleashed a barrage of double-0 buckshot at the enemy. During the four-minute inferno, all the enemy were killed.

The Raiders were raked by mortar and heavy machine-gun fire, and three times that afternoon the Japanese boldly counterattacked. Accompanied by shrill notes on a bugle and shouting “Banzai,” the enemy charged down the center of the island. Running at full stride, they held their rifles over their heads with bayonets fixed, shooting from that position without aiming. They failed to panic the Americans, who let them get as close as they dared and then poured fire into them. The noise was deafening. Eighty-two Japanese were killed.

Food, Medical Supplies, Beer, and Samurai Swords

As enemy snipers picked off some of the Raiders, the Leathernecks regrouped and continued their patrols of the island. They tended their wounded aided by native men and boys. Carlson, meanwhile, believed that he was greatly outnumbered and decided to get off the beach after dark. At midnight, he told every man that he was free to try to get through the surf to the submarines or stay on the beach. Enemy airplanes had bombed and strafed the beach, and only two of the Raiders’ rubber boats were seaworthy. Some of the Marines repaired one of them, however, and then hid both of them. Two large native boats were also made ready. The Leathernecks lashed together a large raft, using two native fishing boats and three rubber boats. Some of the wounded men worked on this project.

By dawn, Colonel Carlson was prepared to surrender, if necessary. He sent out a captain and a corporal to parley with the Japanese. The pair concluded, however, that there were no enemy defenders left alive on the island.

Heartened, Carlson reorganized his two scrambled companies—Major Roosevelt had managed to lead some men out to one of the submarines—and ordered a sweep of the island. The Raiders blew up the radio station, shot two enemy survivors, torched a cache of aviation gasoline, and burned what supplies they could find. Documents were snatched from the Japanese commandant’s office. The Americans also helped themselves to some food, medical kits, beer from the officers’ pantry, and some samurai swords for souvenirs.

On the evening of the second day, the submarines eased into the mouth of the sheltered Makin lagoon to pick up Carlson and his men. The colonel and his detail were the last men to reach the boats. As a great red glare from the burning installations lit the sky, Carlson took a place on the raft and nodded his head in a satisfied manner. The motors sputtered and stopped. The coxswains cursed, and the Marines crossed their fingers. Again the motors sputtered, and then there came a steady purr from one and then both motors. The raft pitched and tossed as it made toward blinker signals from the submarines. It was a tense trip, with the Raiders refueling the motors of their primitive craft as they lurched in the currents.

“Consummate Skill in Operations, High Morale, and Aggressive Spirit.”

Carlson was pleased with the mission. The garrison had been wiped out, Japanese communications had been disrupted, intelligence information had been captured, and the Marine Raider concept had been proven. The Raiders had killed all the enemy defenders for a loss of 30 Americans killed and missing. When they wearily clambered back aboard one of the submarines, Carlson and his men were convinced that all were accounted for, but nine were actually left behind. They were later captured when the Japanese reoccupied the island, and were beheaded.

The dirty, weary Raiders welcomed the clean bunks aboard the submarine, and the naval officers gave up their cabins to the seriously wounded. The wardroom was turned into an operating room, and the mess table became the operating table. The submarine headed at full speed to Pearl Harbor. There, bands and cheers from ships’ crews greeted the Marine Raiders. Admiral Chester W. Nimitz, commander in chief of the Pacific Fleet, went aboard the submarine and congratulated Colonel Carlson and his men. Looking over the captured sword of the former Japanese commandant of Makin Island, he told one of Carlson’s officers, “Very pleased. Very pleased—a very successful raid.”

Carlson was awarded a Gold Star in lieu of a second Navy Cross for his leadership, and his unit was given a blanket citation for “consummate skill in operations, high morale, and aggressive spirit.” After rest and refitting, the Raiders were back in action later that year.

Once again, Carlson’s Raiders found themselves training hard. There were fast hikes up and down cactus-covered hills at Jacques Farm, San Diego, and simulated amphibious landings at Catalina Island and San Clemente in California. This training phase, with the men living in pup tents all the time, lasted three months. Then they shipped out to the Pacific Theater again and set up their base of operations at Espíritu Santo in the New Hebrides.

Now there were six companies in the 2nd Raider Battalion. Sailing aboard converted World War I four-piper destroyers, and landing from Higgins boats, Carlson’s unit scrambled ashore on Guadalcanal in October 1942.

Attacking the ‘Forest’

The Raiders went into bivouac at Aola Bay, 40 miles east of Henderson Field, while the mop-up of Guadalcanal continued. Carlson requested action for his men, and they were temporarily detached for the purpose of attacking a Japanese force along the Gavaga River, where the U.S. Army’s 164th Infantry Regiment was fighting.

Early on November 8, the Raiders left their base camp at Bino and headed inland over mountain trails. Warily, they moved through the tall kunai grass and humid jungles. Coming upon enemy soldiers swimming and bathing in a river, some of the Raiders opened fire on them, but Japanese machine guns in good positions replied and pinned the Raiders down. At one point, a Marine lookout reported excitedly that a forest was moving toward the Raiders’ position. Colonel Carlson looked through his binoculars and saw a company of Japanese, in mass formation, marching across a field wearing cloaks of foliage and twigs. When they were within easy range, the Raiders opened up on the “forest” with their mortars. The “trees” scattered in all directions.

The Raiders pushed on, moving as stealthily as their enemy and hitting them whenever they could. Sometimes it was almost too easy for the Americans to find and kill the Japanese. Sometimes, said Carlson, “it was like shooting ducks from a blind.”

Carlson’s force had intended to spend a week patrolling and harassing the enemy, but the hunting was so good that it stayed more than a month. The Raiders destroyed remnants of the enemy on the Upper Lunga River and collected valuable information about enemy operations and the terrain.

488 Japanese Troops Dead

It was a difficult time for the Americans, but they moved fast and hit the enemy hard. They existed mainly on rice and rations and sometimes joined their native guides in a repast of air-dropped Australian corned beef (called “corned willy” by the Americans). The weather was unpleasant. Sometimes it would suddenly start raining with monsoon force, and just as abruptly stop. There would be no cooling off, and the temperature would again be 120 degrees.

Eventually, after 39 wearying days, the Raiders followed a native guide 25 miles along back trails to the Bino base camp. Their mission was completed. The Raiders had high praise for the heroic natives who assisted them and the other U.S. troops on Guadalcanal. “They were very brave,” said Sergeant O’Brien. “Without them, we couldn’t have made so much distance.” Carlson’s Raiders had marched 150 miles and killed 488 Japanese troops, with a loss of 16 Marines dead and 18 wounded. Some Marine Corps observers called the Raiders’ operation on Guadalcanal the greatest single patrol of World War II.

Nevertheless, the Marine Raiders were looked upon with disapproval by certain officials. After Guadalcanal, the Raiders were consolidated with three other battalions into a Marine Raider regiment. Carlson was placed second in command, but his Gung-ho system was discarded. He was awarded a second Gold Star for his leadership and heroism, and, stricken with malaria, was sent home in the spring of 1943.

After hospital treatment and a few months’ peace at home in Plymouth, Colonel Carlson went to the West Coast to serve as technical adviser to producer Walter Wanger for his motion picture about the Makin Island raid, Gung Ho.

Carlson Becomes a National Hero

Carlson chatted with the star, Randolph Scott, who was playing a character named Colonel Thorwald, based on the Connecticut preacher’s son. When the film premiered in Waterbury, Conn., the Carlson parents and their next-door neighbors, the Mattoons, attended. Directed by Ray Enright, released by Universal Studios, and co-starring Alan Curtis, Noah Beery Jr., J. Carroll Naish, Robert Mitchum, and Rod Cameron, the film was considered to be a creditable recreation of the Makin Island raid. It was full of realistic action, and Scott gave a dignified, compelling performance.

Carlson was by now a national hero, with his picture on front pages and magazine covers. He was holding a staff job at a base in the United States, but he told reporters that he was anxious to return to active duty. He soon got his chance, shipping out for the Pacific again in time to take part in the bloody November 1943 assault on Tarawa atoll as an official observer.

The land battle for Tarawa’s Betio islet began at 9:10 am on November 20. Betio was a well-fortified island about the size of New York’s Central Park. Its capture was the objective of Maj. Gen. Julian C. Smith’s seasoned 2nd Marine Division in Operation Galvanic, the seizure of enemy-held atolls in the Gilbert Islands.

After three days of naval and aerial bombardment, the first waves of Marines in amphibious tractors (amtracs) churned toward the beaches. Machine-gun fire greeted them, and some of the landing craft failed to reach the shore. Initial casualties were light, but it was different for the subsequent waves of Leathernecks. Stunned initially by the American warships’ bombardment, the Japanese defenders now stiffened and intensified their fire. Landing craft were forced to beach themselves on the reefs that fringed the island, and the Marines had to wade ashore through waist-deep water, braving machine-gun fire and shell fragments.

A Precarious Return to Battle

The defenders, as the Leathernecks found out to their cost, had survived the U.S. shelling and bombing in well-fortified pillboxes and sturdy bomb shelters. Marine units were cut to pieces, and men who did manage to struggle ashore and take cover behind coconut logs and a low seawall at the water’s edge were exhausted, disorganized, and sometimes weaponless.

Carlson waited off the reef with a party of Marine officers that included Colonel David M. Shoup, commander of Combat Team 2. Shoup was later awarded the Medal of Honor for reorganizing the assault force and getting the attack moving. After ordering reinforcements ashore to bolster the precarious foothold on Beach Red 2, Shoup and his party landed on the fire-swept pier half an hour after the first wave of Marines had gone ashore.

The Marines struggled to hold on, and it was a desperate inch-by-inch struggle to obtain a grip on the island. Shoup’s battalions eventually managed to carve out a beachhead less than 700 yards wide and no more than 400 yards deep.

The reefs slowed the arrival of reserve units, water, ammunition and medical supplies, but eventually half of the division reserve—aided by tanks and artillery—managed to get ashore. The Japanese stubbornly defended every bunker, but the Marines fought on doggedly. Shoup rallied his men to prepare for an enemy counterattack on the beachhead during the first night, but it never came. The next morning, the Marines, who now had two separate toeholds on Betio, resumed their offensive.

”It Was the Damnedest Fight I’ve Seen in 30 Years of This Business”

That morning, several of the officers breakfasted under a palm tree and reviewed the landing. “Did you see three-eight (3rd Battalion, 8th Marines) and one-eight wading in?” Carlson asked. “They were mowed down like flies. I believe one-eight had a hundred casualties in less than a minute. Guadalcanal was something, but I never saw anything like this. This was not only worse than Guadalcanal. It was the damnedest fight I’ve seen in 30 years of this business.

“If ever blood and guts were shown, it was right there on the part of the Marine division which did the job. The Japanese had more troops than we did. It was the toughest job the Marines ever had in their 168 years.”

Not one to merely sit around and watch others fight, Colonel Carlson was cited for volunteering to carry information through enemy fire from an advanced post to the divisional headquarters.

1,100 killed and almost 2,300 wounded

The bitter, bloody fighting continued as the Leathernecks rooted out the enemy from their bunkers. More units were landed on the tiny island, and the Americans established a perimeter along the southern shore while the enemy were being cleared from other sections.

On the third day, the Leathernecks attacked from both south and west, and that evening a Japanese counterattack was blunted. The final drive, crushing organized resistance on Betio, began at daybreak on the fourth day, November 23. By 1:30 pm that day, the island was declared secured. The 76-hour struggle for Tarawa was over. Of the 4,836-man Japanese garrison, 4,690 were killed. The Marines lost 1,100 killed and almost 2,300 wounded.

By now one of the most decorated Leathernecks in history, Lt. Col. Evans Carlson next took part in his last action, the invasion of Saipan in the Marianas Islands on June 15, 1944, by the 2nd and 4th Marine Divisions.

Carlson served with Chambers’ Raiders, a battalion of the 4th Marine Division led by Lt. Col. J.M. Chambers, who had served with Colonel Merritt Edson’s lst Marine Raider Battalion on Tulagi.

The unit’s objective was Hill 500, a series of rugged rock peaks jutting upward at the southwestern end of Saipan’s mountain chain. From it, the enemy could overlook the airfield and the entire southern portion of the island. The Japanese defenders’ southern defense hinged on Hill 500. Marine artillery hammered enemy positions before Chambers’ battalion moved forward. The Marines fought their way up the hill and set up a defense line for their first night before starting down. The artillery had shattered the enemy defenses, but there were still plenty of snipers around. The next morning started quietly as Chambers’ Leathernecks moved through the gullies beyond Hill 500 toward the foothills of Mount Tapotchau.

Though Shot in the Arm, He Did Not Drop the Wounded Marine

They crossed three ridges and reached a narrow valley ending in a wooded rise. On the left was a cliff and on the right was another ridge. Chambers and Carlson moved forward warily with the point of the Marine line.

All was quiet on the ridge in front of them. It looked like a trap. The Leathernecks were well into the valley when Japanese machine guns opened up on them from caves in the cliff. More gunfire came from both the woods and the ridge. A private with a walkie-talkie was hit by an early burst of fire, and Chambers and Carlson picked him up and started to carry him back. Then a bullet hit Carlson in his right arm, but he did not drop the wounded Marine. He said simply, “I’m hit.”

Carlson suffered a fractured right arm and had another bullet in his left thigh, which chipped the muscle. His soldiering days were over. He was still bandaged a few days later when he was reunited at Pearl Harbor with a smiling Major Roosevelt, his executive officer on the Makin Island raid. Carlson was awarded a Gold Star in lieu of a second Purple Heart (he had won the first in World War I). With characteristic nonchalance, he wrote to his sister Karen, working as an inspector at the Waterbury Tool Co., to say that he felt “pretty lucky” about his wounds.

Physical disability necessitated Carlson’s premature retirement on July 1, 1946. He was advanced to the rank of brigadier general on the retired list because of having been specially commended for performance in combat. The famed Marine Raider sought peace in a cabin on the picturesque slopes of Mount Hood in Oregon, planning to spend his retirement years hunting and fishing. He continued to take an active interest in world affairs, however, and served as national vice chairman of Henry A. Wallace’s Progressive Citizens of America. But his retirement was a short one. Carlson suffered two heart attacks on November 8, 1946, and another, which proved fatal, on May 27, 1947. He died at the age of 57 in Emmanuel Hospital in Portland, Oregon.

Remembering a Warrior and a Hero

The leader of Carlson’s Raiders was buried with full military honors on June 5, 1947, in Arlington National Cemetery. The rites were attended by General Alexander A. Vandegrift, Marine Corps commandant, and other high-ranking Marine Corps and Navy officers.

Carlson had been married twice, to Dorothy Secomb Evans in 1917, and later to Estelle Sawyer Carlson. His only son, Evans C., followed his father into the Marine Corps and, as a lieutenant, joined the Raider battalion on Guadalcanal. He was awarded the Silver Star for “conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity in action” as a platoon leader.

Besides being a skilled, heroic soldier, Colonel Carlson was an accomplished writer and lecturer. He set down his knowledge and beliefs about the Far East in articles in such periodicals as Asia, Amerasia, and the China Weekly Review. He was respected as an observer of the Chinese and Japanese minds. Though some critics found his portraits of China’s Communist leaders to be “suspiciously uncritical,” his book Twin Stars of China was generally considered well written and mature in its judgments.

The Nation magazine wished “that the United States had more military men with the intelligence and breadth of interest with which … Carlson is obviously endowed.” But Colonel Carlson is best remembered for the eloquent eulogy he delivered over the graves of his men who fell on Guadalcanal between November 4 and December 4, 1942, and which was echoed on radio, in newspaper editorials, and by Randolph Scott at the close of the movie Gung Ho.

“What of the future for those of us who remain? Our course is clear. It is for us at this moment, with the memory of the sacrifices of our brothers still fresh, to dedicate again our hearts, our minds, and our bodies to the great task that lies ahead. We must go further and dedicate ourselves also to the monumental task of assuring that the peace which follows this holocaust will be a just and equitable and conclusive peace. And beyond that lies the mission of making certain that the social order which we bequeath to our sons and daughters is truly based on the four freedoms for which these men died.”

Were can you find information on the Army individuals who were was part of Carlson Raider

as Jan 1, 1941 was their at Pearl Harbor he short down three Japanese zero and a mini sub

that day. An his last battle was in taking Okinawa