By Blaine Taylor

In May and June of 1940 the attacking Germans had a supreme authority, Hitler, and an army that—if skeptical, even in places traitorous—was subdued and followed orders with astonishing competence. The Allied leadership who faced this tested and, in Poland, victorious combination of political leader and masterful military could not muster a winning one of their own.

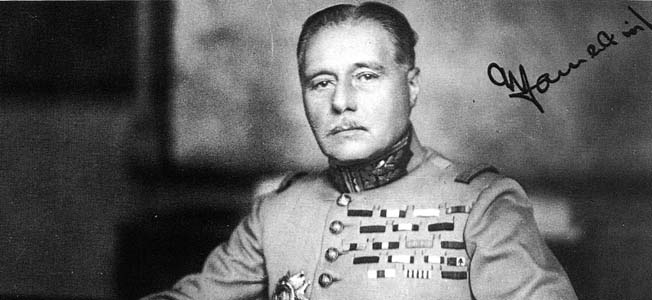

Military Hopes Placed In Gamelin

They had, of course, four languages and four governments to deal with. They placed their military hopes in General Maurice-Gustave Gamelin (1872-1958), about whom his former subordinate, Charles de Gaulle, said, “This man, in whom intelligence, subtlety and self-control reached a very high level, had absolutely no doubt that, in the approaching battle, he was bound eventually to win.”

Gamelin served as Joffre’s Chief of Staff during the First Battle of the Marne. He then successively commanded in combat a brigade, a division, and a corps. In the 1920s he pacified the Druze tribes of the Middle East. In 1931 he was named Chief of Staff of the French Army, and four years later was appointed Commander-in-Chief-Designate (in the event of war) upon the retirement of General Maxime Weygand from that post.

During 1939-1940 Gamelin’s title was Chief of Staff of National Defense and C-in-C Land Forces. Under him was his C-in-C Northeast Front, General Joseph Georges (1875-1951), with whom Gamelin didn’t get along particularly well. In effect, Gamelin was the Generalissimo of an unwieldy structure that included neither the Air Force of General Joseph Vuillemin nor the Navy of Admiral Jean Darlan.

Allies Faced Muddy Political Structure

Politically, the structure was also muddied. Premier Paul Reynaud—who headed the civilian government from March 21 to June 16, 1940—had as a Minister of War a political rival, Edouard Daladier (1884-1970), whom he had succeeded as premier. It did not augur well for harmonious work once the German attack began.

The same was true of the British political situation in London’s War Cabinet. Arthur Neville Chamberlain (1869-1940) had been British Prime Minister for three years beginning in May 1937, and left office on the day of the German offensive in the West, May 10, 1940. The monarch and head of state—King George VI—wanted to appoint as his successor Lord Halifax (the former Edward Wood, 1881-1959), with Chamberlain’s approval.

“But,” according to author M.R.D. Foot, “[Halifax] refused the post: he was no military strategist and probably calculated he could restrain the impulsive Winston Churchill better by serving under him [and] was a self-confessed anti-Semite.” Thus it came to pass that the man whom both Chamberlain and Halifax had opposed politically for a decade left his post as First Lord of the Admiralty in the War Cabinet to become Prime Minister.

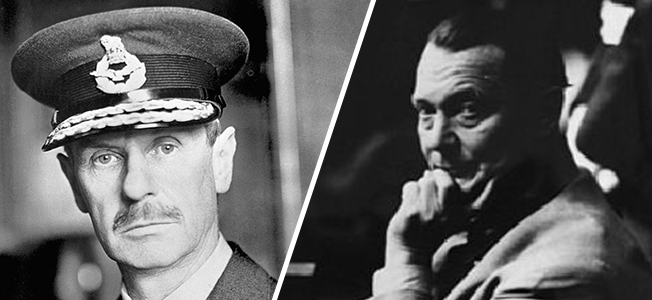

“Tiny” Ironside Named Chief Of The Imperial General Staff

Churchill inherited a murky military command. The reigning Chief of the Imperial General Staff (CIGS) was “Tiny”: General Sir William Edmund Ironside (1880-1959), who was also anti-Semitic, 60, a Scot, and a gifted linguist (he taught himself Arabic while recovering from an airplane accident).

Commissioned an artillery officer, Ironside was in the South African War and later served as a spy in German Southwest Africa before World War I. During the war he was a staff officer with the Canadians until, in 1916, he became commanding officer of the British Army’s Machine Gun Corps, then commanded the 99th Infantry Brigade in September 1918. He led the Allied Expeditionary Force (AEF) at Archangel, Russia, during 1918-1919, and then served on the Sea of Marmara and in Persia.

Despite feeling that he was incompetent as CIGS, Ironside had foresight. He toured Poland in July 1939 and predicted that Poland would quickly be overrun by Germany, that accordingly there would be no Eastern Front there, and that France would not attack the German West Wall (called the “Siegfried Line” by the Allies). He also urged a military alliance with the very Russian Communists whom he hated.

Ironside wanted an eventual BEF of 20 divisions, twice what was actually in place on May 10, 1940. He correctly guessed that Hitler wanted to attack in the autumn of 1939 (bad weather and stubborn generals putting him off). Ironside’s fatal miscalculation as CIGS was that he took for granted that France was secure.

Ironside’s boss, Secretary of State for War Leslie Hore-Belisha (whom Ironside called “The Jew”) thought the coming struggle would be fought not in France at all, but in war-torn Spain, where the rival factions of both left and right, Communist and Fascist, were even then engaged.

When the formation of the BEF was announced on September 3—the day the Allies declared war—the French wanted as its leader Sir John Dill (1881-1944). Much to everyone’s surprise, they got John Vereck, Lord Gort (1886-1946), the man whom Ironside had succeeded as CIGS and whom both he (and virtually everyone else) thought was out of his depth in the top spot in London.

Gort had been commissioned from Sandhurst in the prestigious Grenadier Guards, and in World War I had been awarded the Distinguished Service Order as well as having been mentioned in dispatches eight times. Between the wars he served in China and India. Although promoted to lieutenant general by Hore-Belisha, he fell afoul of his boss, who sent him to France to run the BEF out of spite.

Gort Not Concerned Enough With Big Picture

Nicknamed “Jack” and “Fat Boy,” Gort nonetheless held the coveted Victoria Cross, but was too obsessed with detail and not concerned enough with the big picture. Considered ideal to command a division-sized unit in combat, Gort failed to prepare the British Army for modern, mechanized, armored warfare, didn’t believe in air-ground coordination, and—though a faithful ally to the French—for these reasons was the least likely choice to command the BEF.

Once the shooting started, Gort’s chief accomplishment was to briefly stop the Waffen SS and Rommel’s 7th Panzer Division on May 21 at Arras, and then effect the “Miracle of Dunkirk” that saved the British Army. He later commanded the Home Guard, Gibraltar, and Malta. He, Ironside, and Dill were all eventually promoted to Field Marshal.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments