By James Hart

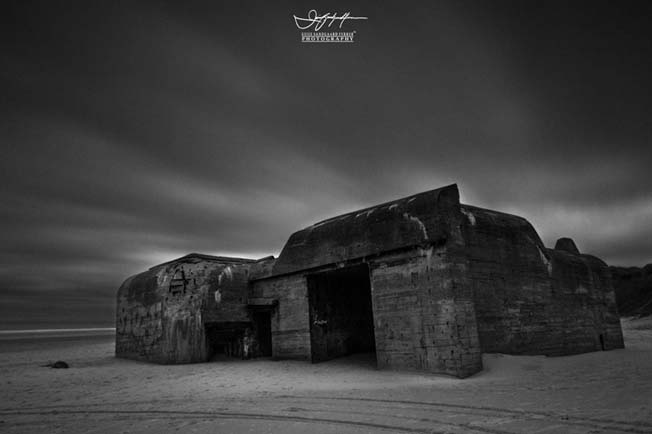

It was built by forced laborers and designed to defend over 2,000 miles of coastline from the Allies. And even today, the Atlantic Wall remains an emblematic reminder of some of the 20th century’s darkest days.

As Adolf Hitler would have you believe it, the wall stretched clear from the northern tip of Normandy to the border between Spain and France. He began fortifying France’s major ports in 1942, but soon, roughly 600,000 workers under the Vichy regime would begin extending the wall farther north.

For awhile, Field Marshal Erwin Rommel was in charge of increasing Germany’s coastal fortifications. He believed the Atlantic Wall was not only important, but essential for his army’s success against an inevitable Allied invasion. “It is absolutely necessary that we push the British and Americans back from the beaches,” he warned. “Afterwards it will be too late; the first twenty-four hours of the invasion will be decisive.”

Today, there is little interest in preserving the remains of the Atlantic Wall. Seen as a historical eyesore and disgrace rather than an artifact, there has been relatively little effort to protect its 70-year-old bunkers from destruction, vandalism, and decay.

In his new collection, however, journalist and photographer Guiie Sandgaard Ferrer has sought to renew the public’s interest. With The Atlantic Wall: The Bunker Session©, Ferrer captures these imposing structures in stunning new detail. We had the opportunity to ask him about his project and how it was first conceived.

What made you decide on the Atlantic Wall for a photography project?

Everything started when I was a kid, and I think it was because of my father. I was 8 or 9 years old and he played a classic war film on the VCR that I will never forget: The Great Escape. I fell in love with the movie, the story, and of course Steve McQueen, who became my hero. This movie was also my invitation to discover WWII, which drove me to dig more and more into everything related to it.

I’m a journalist, and this helped me learn how to research and discover new things. One of these discoveries was The Atlantic Wall.

As a fine-art and landscape photographer, I see the world from another perspective and Nazi bunkers are definitely still life. I try to portrait them in a delicate way, trying to express their historical lines through my work. The building of these fortresses involved tons of hopeless sacrifice, sweat and death: prisoners from the occupied countries were the ones who built these pieces of history that still remain along the Atlantic coast line.

What really drives me to keep on doing this is the fact that people around Europe don’t see these bunkers as a part of their history. They don’t even respect the memories inside the bunkers. And even worse, people vandalize and graffiti them in the most awful possible ways. I haven’t seen people doing this with the Pyramids or the Chinese Wall. So I try to protect history through my work. Plus, the architectural concept of these colossi is amazing. The technology used on these bunkers was so modern at the time. They were so well-made that they still stand tall, facing merciless winters and warm summers.

How accessible were the bunkers that you photographed? Were they still open to the public, or on private land?

In Denmark, where I made these shots, the bunkers are usually on the coastline, so access is extremely easy. But there are some photos I made in remote locations where you need to walk a lot to reach them. And walking in sand dunes is not an easy task when it rains or when the wind blows so hard that the sand grains sting your face, and you have cover and protect your gear. Either way, the final result pays off.

The bunkers are still open. A decade or so ago, they were boarded up, but some people have destroyed the barriers to get inside. The good thing is that the bunkers are still in public land; that´s very good for me. In France and the Netherlands they are inside barbed wire farms, so access is quite difficult. I always talk to the owners and explain what I do so they allow me to get in. In Denmark I only had problems when I was trying to reach the Sperrbatterie-Süd 5 in Løkken, northern Jutland. I was after an M270 bunker that it was in private property.

What is the geographical span of your project? Did you focus on one region, or are the bunkers from different municipalities?

I called my project The Atlantic Wall: The Bunker Session© and is based mostly from Norway to southern France. In the case of my photos made in Denmark, you can see bunkers from many different municipalities in the region of Jutland; that was the area designated for the Atlantic Wall in the west coast of Denmark. It was the same in France and The Netherlands. On the British islands of Guernsey and Jersey, they belong to one municipality. In a parallel way, I’m working on a new project right now that has to do with inland defensive lines: The Siegfried Line and the Alpine Line.

Did you gain a greater sense of that period of history during your time there?

Of course, you can feel history in every inch of their walls. Every time I come across a new bunker, I touch it and pass my hand on the wall. It’s amazing to see how history can capture you once you are inside these buildings. And the silence inside is very frightening.

Is there anything else you would want viewers to know about the photographs?

I would like people to understand that this is part of our culture. It is not a monument; it is a building that belongs to a dark era. But history deserves respect. I would love it if people could see that in my work. A nice wish would be to see no more graffiti on the bunkers.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments