By Eric Niderost

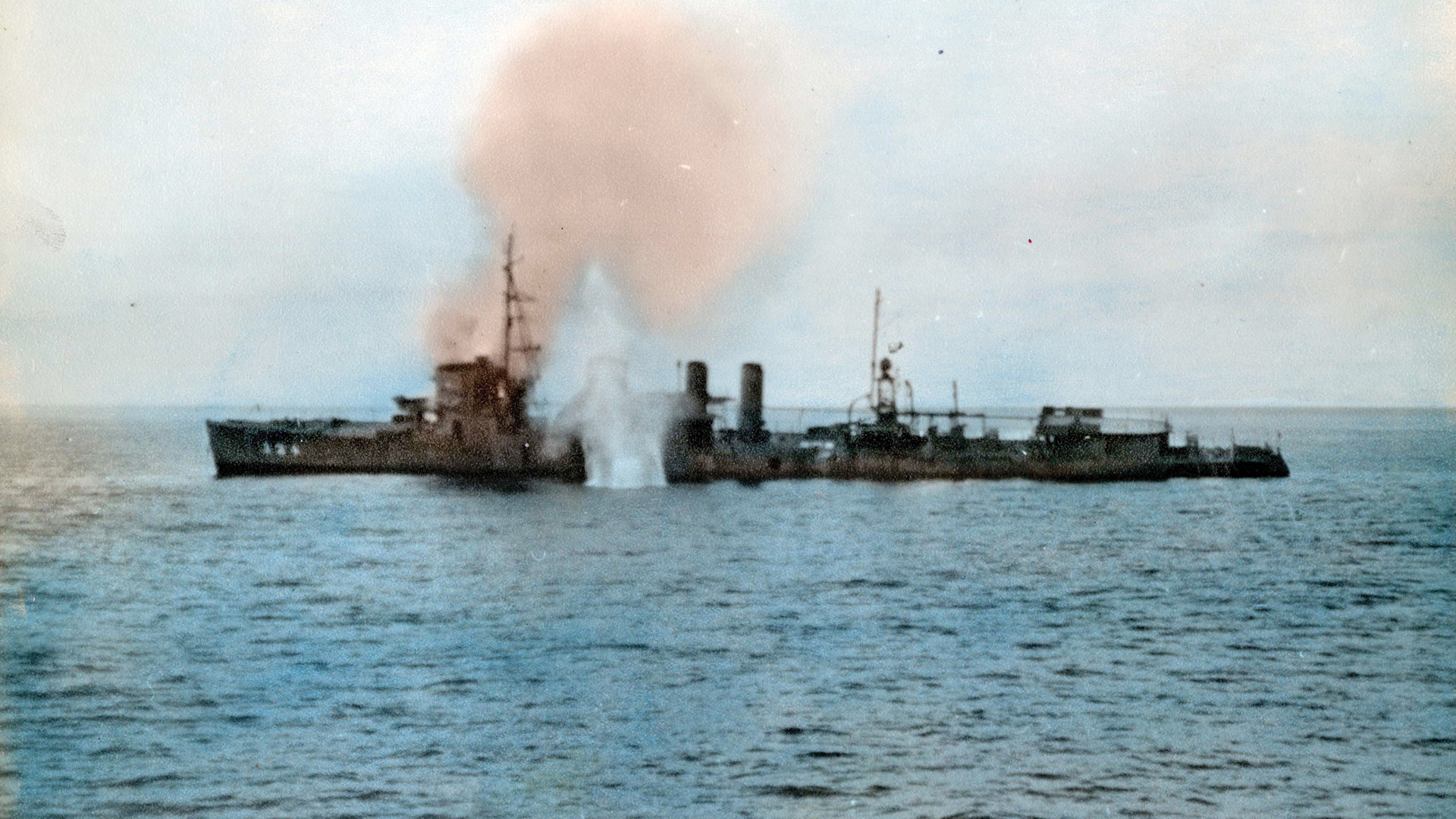

In the predawn hours of September 15, 1944, the official start of the two-month Battle of Peleliu, a powerful fleet of U.S. Navy warships trained its guns on a small coral island in the Palau chain. The ships included the battleships Pennsylvania, Maryland, Mississippi, Tennessee, and Idaho, supported by a host of heavy and light cruisers. When H-hour arrived the guns opened fire, their muzzles spouting great sheets of smoke and flame, and the thunderous noise was so great a man had to shout at the top of his lungs to be heard.

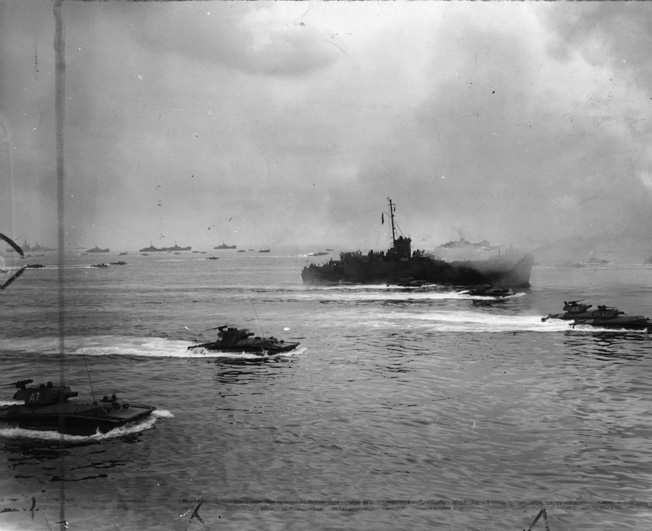

The men of the 1st Marine Division were already in their landing craft, waiting for this preliminary bombardment to further soften up the island’s Japanese defenders. Most of the men were veterans and had earlier breakfasted on helpings of steak and eggs. Even so, the sour smell of diesel oil, combined with the acrid stench of expended cordite from the naval bombardment, must have nauseated the most battle-hardened leatherneck.

Some of the men had daubed their faces for jungle camouflage, and war correspondent Tom Lea recalled that he saw one painted warrior looking over a gunwale with grim determination, “his big hands … in the last moments before the tough tendons drew up to kill.”

These first waves were in a variety of craft, most particularly LVTs (Landing Vehicle, Tracked). They were also called amphibious tractors, or amtrack. Some marines called them “alligators.”

Just ahead, Peleliu was being pummeled by a steady rain of shells. Flames shot high into the air with every ear-shattering detonation, and thick coils of smoke rose to form a pulsating black curtain that enveloped the landing beaches like a dark shroud. The approaching Marines could hope that the Japanese defenders were obliterated by the very intensity of the bombardment. After all, this was the third consecutive day of shelling, and the Japanese had not replied with their own guns.

But such hopes proved far too sanguine. Soon Japanese artillery opened up on the approaching landing craft with a vengeance, the near misses marked by towering geysers of water. It was the first hint that Peleliu might not be the relative walkover that some commanders had predicted. The Battle of Peleliu was to prove a difficult nut to crack, and indeed, some later called it the hardest campaign of the Pacific Theater.

MacArthur Versus Nimitz

Peleliu is a small island about six miles long and two miles wide, shaped something like a lobster’s claw. It is part of the Palau chain, which forms the westernmost “tail” of the Caroline archipelago. In fact, Peleliu was one of the smaller islands of Palau, but its airfield gave it enormous strategic importance—or so it seemed at the beginning of 1944.

By 1944, the Japanese were clearly on the defensive. The United States had gained the initiative, and the technique of island-hopping, while costly, was proving effective. Admiral Chester W. Nimitz’s forces were battling their way though the vast stretches of the central Pacific. In 1943, Tarawa in the Gilbert Islands had fallen to American forces, then Kwajalein and Eniwetok in the Marshalls a few months later.

The Marianas were the next target, and Tinian, Saipan, and Guam were secure by the summer of 1944. There was particular satisfaction in the liberation of Guam, which had been an American possession before the war. Ultimately the goal was the invasion and conquest of the Japanese Home Islands. But how would the Americans achieve this objective? The Pacific was vast, and possibilities endless. The debate grew, sharpened by the differing opinions and conflicting personalities of America’s top commanders.

While Nimitz island-hopped to the north, General Douglas MacArthur was making steady progress though the South Pacific. It had been a long, tough slog since August 1942, when America launched its first major offensive at Guadalcanal. Since then MacArthur had made his way through the Solomons, then seized control of the greater part of New Guinea. It was no secret that MacArthur wanted to liberate the Philippines, but some of his Navy colleagues did not concur.

To resolve the impasse, President Franklin Roosevelt met with MacArthur and Nimitz in Hawaii in July 1944. Each man presented his plan and his vision to the commander in chief. MacArthur wanted to liberate the Philippines, using it as a springboard to go on to Okinawa and then to Japan. Nimitz wanted a more direct, “rapier-like” thrust that would bypass the Philippines entirely.

Nimitz suggested that Okinawa and Formosa (Taiwan) be the primary targets instead. They would serve as admirable staging areas for the invasion of the Japanese Home Islands. The admiral also thought that American forces should invade the Chinese mainland. A large part of the Japanese Army was stationed in China, and at times the Americans’ Chinese allies under Chiang Kai-shek were hard-pressed.

After careful deliberation Roosevelt accepted MacArthur’s ideas. The Philippines would be a major stepping-stone on the way to Japan. But MacArthur’s plans for the Philippines suddenly thrust the Palau chain, and most particularly Peleliu, into the limelight. The Palaus were about 600 miles east of the Philippines, and Japanese airfields there might threaten MacArthur’s right flank. It was decided that Peleliu must be taken and the danger neutralized.

The Battle of Peleliu and “Operation Stalemate II”: Ironic in Hindsight

The Battle of Peleliu was code-named Stalemate II, a name that seems ironic in hindsight, because initially the campaign was viewed with relative optimism. The main task of securing the island was given to the 1st Marine Division, a largely veteran unit that had seen action at Guadalcanal and New Britain. The 1st Marine Division consisted of the 1st, 5th, and 7th Marine Regiments (infantry) and the 11th Marines (artillery support).

The campaign’s secondary objectives would be handled by the U.S. Army’s 81st Infantry Division. The 81st was going to take Angaur Island, a part of the Palau chain that was just to the south of Peleliu. The division had been reactivated in 1942, and the Palau effort was going to be the first taste of battle for what were essentially green troops. But their primary mission encompassed more than just Angaur. They were also to provide a reserve for the 1st Marine Division if needed.

It all depended on the Marines. If the Marine effort bogged down or faced unexpected resistance, the 81st would be ready to come to their aid. If, however, the Marines had the situation well in hand, then the 81st would be free to pursue its own mission at Angaur.

Major General William Rupertus, commander of the 1st Marine Division, was optimistic about the coming campaign and confident his Marines could secure the island in a few days. An old-school leatherneck, he was steeped in Corps tradition and fiercely territorial when it came to other branches of the military. He frankly did not want any part of the 81st, lest the Army steal away some of the Marines’ glory.

An Overly Optimistic Plan

The Marines were told they would make short work of the enemy. After all, the 1st Marine Division would be a reinforced one, larger than most. Yet a few officers had doubts, doubts that were not assuaged by the prevailing optimism around headquarters. The rule of thumb, born of long and bloody experience, held that a successful amphibious invasion should outnumber the enemy by three to one. On paper, the division would number around 28,000 or so, while enemy numbers were known to be about 10,000 at Peleliu.

It sounded like the three-to-one ratio was being maintained, but these soothing figures were somewhat less than accurate. Colonel Lewis “Chesty” Puller, commander of the 1st Marine Regiment and a growing legend in the Corps, pointed out that the numbers included artillery and other specialists. There were only 9,000 riflemen in the division—and it was the foot-slogging, long-suffering rifle companies that would ultimately mean the difference between victory and defeat.

Puller’s objections were ignored or downplayed by his superior officers. General Rupertus dismissed Puller’s concerns and continued to exude a kind of cheery confidence. Rupertus thought that the island would be secure within five days or so of the initial landings. As events unfolded, Puller and his 1st Marines would suffer the consequences of the general’s dogged optimism.

Fukkaku Tactics in the Absolute Defense Zone

In the meantime, the Japanese were far from idle. In fact, Peleliu was going to be the proving ground for a major shift in Japanese tactics. In the early months of the Pacific War the Japanese military was infused with a zeal that often became fanatic. Bushido—the way of the warrior—was the ideal, an embodiment of the samurai spirit of old. Rabid nationalism fed by shrill propaganda made Japanese soldiers look with contempt at the American “red-haired barbarians.”

In the first years of the war it was customary for Japanese troops to contest every inch of soil. Samurai swords waving, Japanese officers would lead human-wave banzai attacks, only to be cut down by machine guns, rifles, artillery, and mortars. It soon became clear to even the most tradition-bound Japanese that the old assumptions had to be changed. Samurai spirit could not overcome the enemy’s modern weapons.

In March 1944, Lt. Gen. Sadae Inoue met in Tokyo with Japanese Premier Hideki Tojo to discuss future operations. Tojo, who was also war minister and a noted hard-liner against the United States, was realistic enough to see changes had to be made. It was plain that Japan simply did not have the resources to decisively defeat America. The best that could be hoped for was a negotiated peace.

Tojo advocated what later became known as fukkaku tactics. This envisioned a war of attrition that would make the Americans pay dearly in blood and treasure for every position they gained. The Japanese would use natural features to their advantage by constructing pillboxes and bunkers amid coral ridges and rock outcroppings. They would also make use of natural caves, enlarging them to provide cover for hundreds of soldiers.

Peleliu was part of the Absolute Defense Zone, literally a last-ditch protective cordon guarding the Japanese Home Islands. Tojo hoped that the United States would have no stomach for a long, drawn-out contest. Bled white, the Americans would be eager to come to the negotiating table. They might even acquiesce to Japan’s brutal conquest of China and Southeast Asia.

Augmenting Peleliu’s Natural Defenses

General Inoue was appointed commander, Palau District Group, and soon flew to his new assignment. The Palau chain actually consists of about 100 islands scattered in a wide arc running from southwest to northeast across 100 miles of the Pacific. The Japanese administrative center for Palau was located on Koror, roughly 25 miles from Peleliu. Koror was Inoue’s headquarters, but survey flights of Palau convinced him that Peleliu and neighboring Anguar would be the main enemy targets. The islands were small and relatively isolated, but their airfields made them important.

Inoue was an experienced officer who knew he needed a good man on Peleliu. His choice fell on Colonel Kunio Nakagawa, well known to be courageous and a superb tactician. To all intents and purposes Nakagawa would have full operational control at Peleliu, with little or no interference from superior officers. It was an excellent decision from the Japanese point of view because it was Nakagawa who was largely responsible for Peleliu’s tenacious defense.

Accounts vary slightly, but Colonel Nakagawa was expected to have around 10,000 defenders under his command. Nakagawa probably placed greatest reliance on the men he knew best, his own 2nd Infantry Regiment (Reinforced). The 2nd Regiment had fought in China, and its the noncommissioned officers, always the backbone of any army, were tough and experienced. There were also naval personnel and some Korean construction workers.

The island’s geography greatly helped Japanese strategy. The southern end of the island was fairly level and covered with scrub, while the proposed Marine landing beaches to the southwest were shaded by coconut palms. Nakagawa posted one battalion of troops there, but they were expendable, meant only to delay and bloody the enemy.

Nakagawa’s real defense would center on the Umurbrogol Mountains, a rocky chain of craggy hills, draws, and ravines that formed the island’s backbone. “Mountains” is a misleading term, since the highest peaks only reached around 300-500 feet, but the Umurbrogols dominated Peleliu and provided an excellent vantage point from which to observe enemy movements.

The Japanese made Umurbrogol even more formidable by expanding its maze of natural caves, blasting out galleries in the sharp-edged coral and rock that could accommodate anywhere from a dozen to 1,000 men. Many of the caves had openings that concealed firing embrasures, and some were protected by sliding steel doors. These caves not only bolstered the defense, but also provided protection from the American naval bombardment that Nakagawa knew always preceded amphibious assaults.

Surviving the Artillery Barrages

The Americans had little inkling as to what was in store for them. Aerial reconnaissance photos, usually reliable, proved deceptive in hindsight. From the air Umurbrogol seemed a gently undulating series of hills, green and lush with tropical vegetation. But the jungle vegetation muted Umurbrogol’s sharp coral ridges, sinkholes, and craggy peaks. Only after this jungle mask was removed by naval bombardment was the full labyrinthine horror revealed.

The assault on Peleliu began when Navy warships initiated a three-day artillery barrage of the tiny island. In addition to the shelling, aircraft from nearby carriers dropped 500-pound bombs. It is estimated that the Navy fired 519 rounds of 16-inch shells and 1,845 rounds of 14-inch shells during this preliminary softening up of the target. But in the end it was all sound and fury signifying nothing. The Peleliu caves made excellent bomb shelters, so all the Japanese had to do was hunker down and wait out the bombardment.

To American observers scanning the beaches with field glasses, watching great pulsating pillars of smoke rise high into the sky, the bombardment was a success. In fact, Admiral Jesse Oldendorf soon declared he had “run out of profitable targets.” The illusion was reinforced by superb Japanese fire discipline. Not one of Nakagawa’s guns replied to the bombardment, which fostered the illusion that most if not all of the defending artillery had been knocked out.

First Contact With the Enemy

Chesty Puller’s 1st Marines were assigned the northern (left flank) beaches, which planners code-named White Beach 1 and 2. Once ashore, they were to guard the 5th Marines’ flank and at the same time push inland. At a certain point the 1st Marines would pivot, striking northward into the Umurbrogols, which planners merely called “high ground.”

In contrast, the 5th Marines would be in the center, landing on Orange Beach 1 and Orange Beach 2. Their initial mission would be to secure the airfield, which was one of the main reasons why the Americans were trying to take the island in the first place. The 5th Marines were commanded by Colonel Harold “Bucky” Harris. He was new to the regiment but was also a career officer with extensive prewar experience.

The 7th Marines, Colonel Herman “Hard-Headed” Hanneken commanding, would anchor the left (southern) part of the assault on what was code-named Beach Orange 3. They would cut across the island, isolating and eventually securing Peleliu’s southern reaches.

The Marines landed at 8:32 am on September 15, 1944, just two minutes behind schedule. The first wave was preceded by armored amphibian tractors (LVTAs) mounting 75mm howitzers. Their main mission was to engage and ultimately neutralize artillery positions or other strongpoints missed by the naval and air bombardment.

The LVTAs and following LTVs plowed through wire-controlled mines lurking around the island like a lethal necklace. These devices were not true mines, but aerial bombs adapted for the purpose. Luckily the naval bombardment had cut many control wires, rendering them useless. Even those that were still intact failed to detonate, mainly because their operators had been blinded by smoke.

It was the last bit of luck the Marines would experience for many a long day. As soon as the LVTAs and LVAs came within range, they were hit by a deadly barrage of 47mm fire supplemented by sprays of 20mm machine-gun bullets. Much of the fire came from the right and left flanks, where Nakagawa had built concrete emplacements.

The landing craft had to run a gauntlet of enfilade fire, and many shells tragically found their mark. Twenty-six LVAs took direct hits within the first 10 minutes, and no less than 60 were destroyed or damaged within the first hour and 40 minutes. The beaches and shallow reef waters were littered with burning wreckage, and some Marines abandoned their crippled alligators and waded ashore carrying water and ammunition.

The 1st Marines ran into trouble almost immediately. A Japanese 47mm shell scored a direct hit on Colonel Puller’s LVT, nearly killing him. Another Japanese shell wiped out his entire communications section, hampering his command capabilities. Worse was to come.

Tanking “The Point”

Fighting was heavy all along the landing beaches, but the flank units, the 1st Marines on the left and the 7th Marines on the right, took the most punishment. Combat artist Tom Lea recalled, “I saw a wounded man near me … His face was half bloody pulp. He fell behind me, in a red puddle on the white sand.” Private First Class E.B. Sledge of the 5th Marines grimly remembered, “Shells crashed all around. Fragments tore and whirred, slapping the sand and splashing into the water a few yards behind us.”

Puller’s 1st Marines started inland but had advanced only 100 yards from shore when they encountered a 30-foot-high coral ridge. The ridge, soon christened “the Point” by the Marines, was honeycombed by numerous Japanese defensive tunnels and emplacements. Japanese engineers had opened holes on the coral, then resealed them, leaving just enough room for the snout of a machine gun or other weapon to poke out.

The 1st Marines could scarcely believe their eyes; the Point was not on any map and apparently had not been even targeted by U.S. Navy guns. Quite apart from holding up the advance, the Point also was raking the landing beaches with fire. It had to be taken, but frontal assaults were proving costly. The only way to get the job done was to move around the flank and take it from behind.

Colonel Puller assigned this daunting task to Captain George P. Hunt of K Company, a veteran officer who had seen active service on Guadalcanal. K Company moved off at once, but the going was anything but easy. There were many reinforced concrete pillboxes that seemed to spring up on every side like malevolent mushrooms. The men of Company K knew their business and resorted to a simple but effective formula. Pillbox embrasures were blanketed by small-arms fire and smoke, enabling Marines to get close enough to throw explosive satchels or rifle grenades into the slits.

The Point was finally won when its principal fortification, a large reinforced concrete blockhouse mounting a 25mm gun, was finally taken. A Corporal Anderson launched a rifle grenade into the blockhouse, which ricocheted off the 25mm gun muzzle and landed deep into the casement, setting off the ammunition stored there. A series of spectacular explosions gutted the blockhouse, flames and smoke rising into the stifling tropical air. Some of the defenders, their uniforms ablaze, tried to escape the holocaust. They were cut down by Marine bullets.

Holding Hard-Fought Ground

Hunt had taken the Point, but he was isolated and night was falling. For the next 30 hours Company K clung to its hard-won prize against furious Japanese counterattacks. The Japanese assaults were flung back, though at heavy cost. When Hunt and his men were relieved, Company K was a decimated shadow of its former self. The captain had only 18 men remaining at the Point, clinging to real estate made precious by its cost in lives. In overall numbers Company K, once numbering 235 men, had only 78 survivors.

In the center, the 5th Marines were making good progress, though the Japanese contested every inch of rock and coral. By the afternoon of the first day, the 5th Marines had reached the airfield, one of the major objectives of the campaign. But Nakagawa was not going to give up the airfield without a fight, so he launched a major counterattack with tanks and infantry.

This was not a crazed banzai charge but a serious and disciplined effort led by around 15 Type 95 Ha Go light tanks. Unfortunately for the Japanese, the tanks got too far ahead of the infantry, save for a handful of soldiers clinging to the outside of the hulls. The Americans were expecting just such an attack and were ready for it. Marine artillery soon found its mark, the effort supplemented by the firepower of M4A2 Sherman tanks. All the Japanese armor was soon knocked out, and the supporting infantry slaughtered or forced to fall back.

“Maintain Momentum”

The Americans were on Peleliu to stay, but it was obvious to anyone who opened his eyes that the conquest of the island was not going to be the cake walk everyone expected. Yet, General Rupertus continued to be almost pathologically optimistic in the face of slow progress and mounting casualties. By D-day plus three, the 1st Marines had suffered 1,236 casualties, but Rupertus was still urging Puller to “maintain momentum,” as if this oft-repeated mantra would itself bring victory.

Although there was hard fighting all over the island, the Umurbrogol “meat grinder” was probably the worst. On the second day, temperatures reached 105 degrees Fahrenheit in the shade, and later soared to as high as 115 degrees. Intermittent rains brought no relief—only a muggy, steam bath atmosphere that sucked the moisture out of every pore and wilted the toughest leatherneck. Heat prostration became as deadly as enemy bullets.

Rupertus continued to insist that the situation was well in hand and that Peleliu would fall in a few days. Yet, casualties were getting so high almost anyone who was able-bodied enough to carry a rifle was being put into the battle line. Engineers, pioneers, and even headquarters personnel were sent up to fight.

African American Marines also came forward to volunteer for combat duty. They were men of the 16th Field Depot, support troops who brought up supplies and ammunition. At the time, African Americans were in segregated units, in this case specifically the 11th Marine Depot Company and the 7th Marine Ammunition Company. It was a time of widespread racial prejudice within the military, but because of the crisis their services were readily accepted. The black Marines also helped evacuate critically wounded men under heavy fire.

General Rupertus’s misplaced optimism gave the green light for the Army’s 81st Division to begin its invasion of Anguar on September 17. The Anguar operation was a success, secured with relatively light casualties, at least by Pacific War standards. Its mission essentially accomplished within a few days, the 81st stood ready to assist the Marines in securing Peleliu. Rupertus continued to refuse all assistance.

“I Just Wanted to Kill”

By September 23, the 5th and 7th Marines had finished their assigned tasks. The airfield was secured and the southern end of the island in American hands. After that date Marine fighter aircraft began to arrive on the island, where they provided air support for their beleaguered comrades on the ground.

But the 1st Marines continued to take heavy casualties, enduring some of the heaviest and most brutal fighting of the entire Pacific War. Umurbrogol’s steep valleys, narrow ravines, and rocky draws were death traps where every inch of coral was paid for in blood. Days of bloody, ceaseless combat were scarcely relieved by a few hours of fitful sleep at night.

Some leathernecks found their emotions numbed by the sheer horror that surrounded them in this living hell. Love, honor, and friendship were rendered meaningless, and before long nothing was left, not even basic human decency. One 1st Marine Regiment veteran recalled, “I resigned from the human race. We were no longer human beings. I fired at anything in front of me, friend or foe. I had no friends. I just wanted to kill.”

Holding Hill 100

On September 19, Puller’s 1st Marines were still battling their way into the Umurbrogol, also called “Bloody Nose Ridge.” Around noon, Captain Everett Pope of Company B, 1st Battalion, 1st Marines was ordered to take Hill 100, a knob of high ground that dominated a path called the East Road. Company B had landed with 242 men and was now down to 90 effectives, but this was typical for the 1st Regiment, which was being bled white.

After hours of hard and bloody fighting, Pope and his men managed to reach the summit of Hill 100 only to realize that existing maps were wrong. Hill 100 was not an isolated knob, but part of a ridge that connected to a higher knob 50 yards away. The Japanese held that higher knob, and they soon began pouring fire down on Company B.

The Japanese also opened up from a parallel ridge to the west, exposing Company B to a deadly cross fire. Pope knew he was in a perilous situation; he was completely surrounded by the enemy and cut off from help. He might have attempted a breakout, but in the end elected to stay. This ground had been bought at a heavy price, and the exposed position of Company B might actually blunt Japanese attacks on the rest of the battalion below.

Pope and his men set up a defensive perimeter that the Marine captain later recalled was about the size of a football field. Company B did have some mortar support, but since they were surrounded they only had what ammunition they originally took with them. There were about two dozen Marines left to hold Hill 100.

The sun went down, beginning a new phase in the battle for the hill. The Japanese launched a series of counterattacks that lasted all night. It was a time when the sounds of men screaming for help or crying in pain mingled with the staccato chatter of gunfire, a terrible cacophony that echoed and re-echoed through the darkness.

Fighting became hand to hand. At one point Lieutenant Francis Burke and Sergeant James McAlarnis were attacked by some Japanese soldiers at close quarters. One Japanese thrust a bayonet into Burke’s leg, but the lieutenant pummeled his assailant with his fists. While Burke was occupied, McAlarnis used a rifle butt on a second attacker. The two Marines then pitched the Japanese bodies down the slopes.

Dawn came, probably the most beautiful morning the survivors had ever seen. Toward the end of the fight Company B’s ammunition was so low the men were pitching rocks at the enemy—not that they expected to hit anybody hard enough to do damage. The captain later explained that the Japanese would delay an attack for a moment, thinking the rocks were grenades. To keep the enemy off balance the Marines occasionally threw a real grenade, part of their ever-dwindling supply.

At last, even courage had to give way before superior numbers. The Japanese were getting ready for yet another attack, but Pope received orders to withdraw from Hill 100. In the end only nine men, Pope included, successfully made it back to American lines. For his heroism, the wounded Everett Pope won the Medal of Honor. Hill 100 was not retaken until October 3, almost two weeks later.

Stubborn Interservice Rivalry

General Rupertus continued to reject any notion of help from the Army’s 81st Division. Rupertus would fall back on the same shop-worn optimism that the Marines would take Peleliu “in a few days.” But Rupertus’s superior was not so sure. Maj. Gen. Roy Geiger, commander of the III Amphibious Corps, landed and personally inspected the 1st Marine Regiment’s positions.

General Geiger was appalled. It was plain to see that the 1st Regiment was a regiment in name only, chopped up and pulverized by the Battle of Peleliu meat grinder. Even Chesty Puller was exhausted, worn down by the constant strain of trying to achieve nearly impossible objectives with dwindling manpower.

Geiger had seen enough. The Corps commander made his way to Rupertus and told him that the Marines were going to get support from the 81st Division. By some accounts the interview was heated because Rupertus refused to accept the fact that his division was being decimated. Interservice rivalry also played a role, because Rupertus stubbornly considered Peleliu to be a Marine operation exclusively. It was almost as if he did not want the Army to share the “glory.”

The 81st Division’s 321st Regimental Combat Team landed on Peleliu’s western beaches on September 23. The 1st Marine Regiment was withdrawn entirely from the campaign. It would take some time for the men to rest and recuperate and for the shattered regiment to rebuild. Estimates vary, but the Japanese inflicted roughly 1,672 casualties on the 1st Regiment in less than 200 hours. The 1st Battalion of the 1st Regiment suffered a 71 percent casualty rate; only 74 men from nine rifle companies were left standing.

The Army Takes the Show

By the end of September, the Japanese were confined to the Umurbrogol Mountains, their last-ditch redoubt. Once again, it was a matter of clawing though heavily defended ridges and underground caves. Fighting was so heavy that General Geiger decided to withdraw the decimated 5th and 7th Marine Regiments, in other words, what remained of the original 1st Marine Division. They were withdrawn the third week of October.

It was now an Army show, but the fighting did not lessen in intensity. The Umurbrogols were surrounded, and the Japanese defensive perimeter slowly shrank to a pocket about 400 by 900 yards. By the end of September, Peleliu’s airfield—dubbed MAB (Marine Airbase Peleliu)—was fully operational. Grumman F6F-3N Hellcats and Vought F4U Corsair fighter-bombers provided close air support for the advancing Americans.

The island was so small that it took less than 15 seconds to arrive on target after takeoff, not even enough time for the Corsairs to retract their landing gear. At one point there was a bombing run on a Japanese strongpoint only 1,000 yards from MAB, close enough for bomb fragments to pepper the airfield.

The contest dragged on into November, though it was plain the Japanese were fighting a losing battle. Japanese forces in the northern Palaus had tried to reinforce Nakagawa’s dwindling garrison, but with limited success. A convoy of approximately 15 Japanese barges loaded with troops attempted to run the American gauntlet of ships and airplanes. They were discovered, and most were sent to the bottom. Some 600 bedraggled Japanese made it ashore, but without most of their equipment.

A Late Surrender

The last weeks amounted to what was essentially a siege. American forces used flamethrowers and napalm to great effect, and heavy artillery and air attacks provided essential support. Eventually, armored bulldozers collapsed cave entrances, entombing Japanese soldiers within the bowels of the earth.

Peleliu was finally secured by the end of November 1944, when organized Japanese resistance ceased. Colonel Nakagawa committed suicide after ordering his regimental flag burned. Virtually the entire Japanese garrison of 11,000 was wiped out. The record shows that 202 prisoners were taken in the campaign, and only 19 of these were Japanese. The rest were Korean or Okinawan laborers.

The Peleliu campaign was one of the bloodiest of the entire Pacific War, but it had a curious postscript. On April 27, 1947, Lieutenant Tadamichi Yamaguchi led 26 survivors out of hiding and handed over his samurai sword in a token of surrender. Yamaguchi and his men made the last formal capitulation of World War II, a conflict that had ended 20 months before in 1945. (Get the inside story on Pacific battles both famous and forgotten with WWII History magazine.)

In his 2018 book, “On Desperate Ground,” author Hampton Sides, citing Gail B. Shisler’s 2009 biography of Gen. Oliver P. Smith, writes the following: “Pelieu proved to be one of the costliest battles of the Pacific war, yet, tragically, the island could have been avoided altogether. Smith came to realize, said a biographer, ‘that all of that blood and sacrifice and pain had been for no strategic gain.’ Peleliu hung over him like a curse. He did not want to go down that road again. Losing Marines was one thing; losing them in the service of a dubious and ill-conceived strategy, he though, bordered on the obscene.” p. 177

It was pointless because MacArthur had changed the invasion site of the Philippines from Mindanao to Leyte, and the airfield at Peleliu was too far away from Leyte to be a threat.

You don’t have to capture an airfield to render it unusable to the enemy. Angaur was close enough to Pelieu that the airfield could of been suppressed by long range artillery fire. Pelieu was isolated, no planes, no fuel, no ordnance, no spare parts equals no threat. Admiral Halsey recommended that the operation to capture Peleliu be cancelled but his recommendation was ignored. Huge error in judgment!

Good article. However, nobody WINs the Medal of Honor or any other award for heroism. There is not a contest involved with the exception of staying alive and protecting the warrior to the left or right. All medals are awarded and received one their own merit.

Thank you

U.S. Army, retired (1985-2007)

Thank you for pointing out that the CMH isn’t “won”. Too many people forget that fact. Yes, hindsight allows people to “second guess” acts committed either through error or mistake, yet during this time, the U.S.A. was engaged in vicious & unrelenting battle with a ruthless & intractable enemy, & when blows are thrown, it is almost impossible to evaluate & change tactics/direction when each other’s hands are on each other’s throats! So just as the Japanese Imperial Military had changed tactics just before this battle, the American Military ALSO changed some of its tactics AFTER this, reflecting the old truth of action>reaction.

Tarawa was another costly operation of questionable necessity. Problem was that when the higher ups developed a strategic plan, it was difficult to change even when reality and circumstances changed. When US forces reached the point when they had operational control of the air and sea around Japanese held islands, the necessity for land invasion greatly diminished or disappeared altogether.