by John Wukovits

The heated reaction by the Marines to the slaughter at the Goettge Patrol, answered in kind by the Japanese, led to some of the fiercest combat seen in the war. Neither side granted or received much quarter.

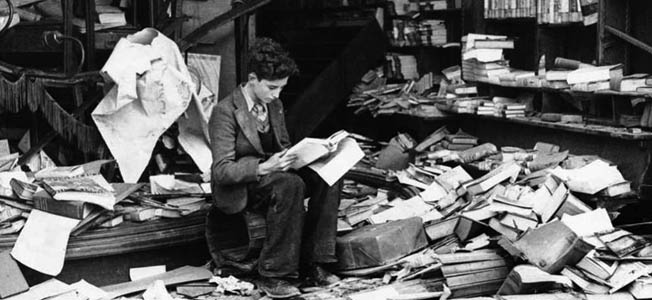

While this occurred in the vast Pacific, the home front lived in blissful ignorance, or at least in purposeful denial. People in the United States received hints of the war’s awful horrors, but from thousands of miles away, many civilians refused to acknowledge the hellish nature of combat in the Pacific.

[text_ad]

This was evident following the war. As related in John Dower’s 1986 book, War Without Mercy: Race and Power in the Pacific Conflict, correspondent Edgar L. Jones, who had covered different campaigns in the Pacific, wrote in the February 1946 issue of Atlantic Monthly of his nation’s stunned reactions to the war’s brutality as they learned of it from returning veterans and former prisoners of war. He commented that atrocities, such as shooting prisoners or destroying hospitals, existed on both sides, then mused in stunned surprise, “What kind of war do civilians think we fought, anyway?”

On November 17, 1943, 20th Century Fox released the movie version of Richard Tregaskis’s book, Guadalcanal Diary. Directed by Lewis Seiler and starring Preston Foster, Lloyd Nolan, William Bendix, and future Oscar winner Anthony Quinn, the movie supposedly portrayed events in the Solomons as described by Tregaskis. The movie accurately depicted the harshness of the jungle terrain and the ferocity of the Japanese, but as was true of most Hollywood productions during the war, discrepancies and exaggerations exist.

The movie followed a “typical” Marine platoon through its experiences on Guadalcanal. In an effort to show that most segments of American society were involved in the war effort, the platoon featured a blond-haired, energetic youth, a Spanish-American, a Brooklyn cab driver, and a brave chaplain who loved Notre Dame.

Most of the movie was shot on location at Camp Pendleton in California. Many of the Marines who were stationed there were filmed while on maneuvers and some were given small speaking parts.

The film frequently resorted to sentimentality. The opening shots contained Marines aboard transports singing religious hymns, then chatting about girlfriends back home. Good-natured ribbing seemed to be their favorite pastime.

One area that accurately reflected reality came in the statement of one of the movie’s Marines, uttered during an intense Japanese bombardment of his position. His statement, included in Colin Shindler’s Hollywood Goes to War, could have been made by almost any fighting man in any theater. “I ain’t no hero,” said the Marine. “I’m just a guy. I’m here ’cause someone sent me and I just wanna get it over with and go home as soon as I can.”

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments