By Terry Gore

Robert the Bruce, self-proclaimed King of the Scots, grasped his axe as the heavily armored English nobleman, a member of the vanguard of the 20,000-strong English army, bore down upon him, lance leveled and clods of earth arching from his charger’s hoofs. Robert’s own mount, a much smaller but more agile horse than the heavy Flemish chargers that the English knights rode, would be of little use in a mounted charge against the much heavier armored opponent, but to turn and run from the attack would be unthinkable.

The English nobleman, a man well known by his heraldic trappings, was none other than the Bruce’s hated enemy, Sir Henry de Bohun. The Scottish king knew that he could not be seen running in fear from this poorly matched contest. Thousands of Scotsmen, desperately in need of a morale-building victory, watched from their positions on the wooded slopes above the stream called the Bannockburn. They gazed out upon an English invasion force four times their own number, and this sheer disparity alone would normally be enough to shake the fragile morale of the 5,000-strong Scottish army. To see their king run away from a clear challenge—that would be intolerable. Robert gripped his axe and urged his mount in a slow walk toward the fast-closing de Bohun.

Scotland in the latter part of the 13th century suffered a dynastic struggle reminiscent of a Shakespearean tragedy. In 1286, when the lustful and headstrong King Alexander III fell to his death on the rocks of the Scottish coast during a night ride on a wet and slippery path (or was murdered as some have theorized), the throne of Scotland had been left vacant. The only direct descendant of Alexander, a young daughter living in Norway, died a short four year later, leaving a power vacuum over which a dozen Scottish factions fought, each desiring to become the next ruling house.

“He is Valiant as a Lion, Quick to Attack the Strongest”

Unable to settle their dynastic troubles, the Scottish nobles made the mistake of sending to the English King, Edward I (Longshanks), asking him to arbitrate. Edward, portrayed as a cunning and ruthless tyrant in the movie Braveheart, wasted little time in making a bargain with the Scottish nobility. A contemporary had scarcely more regard for Edward than Hollywood:

“He is valiant as a lion, quick to attack the strongest.… [He] is a panther in fickleness and inconstancy, changing his word and promise.… When he is cornered he promises whatever you wish but as soon as he has escaped he forgets his promise. The treachery or falsehood by which he is advanced he calls prudence and the path by which he attains his ends, however crooked, he calls straight and whatever he likes he says is lawful.”

As brother-in-law of the dead Alexander, Edward felt it in his own best interest to resolve the situation. Thus he chose to appoint an acceptable leader to the throne of Scotland and then arrange to have the fractious Scottish nobles grant him suzerainty over their country. Edward appointed John de Baliol as the new King of the Scots.

De Baliol did have a tenuous link to the ruling family of Scotland. His grandfather had been married to the niece of a previous Scots ruler, William the Lion. Other than that, there was little of Scotland about John de Baliol. He was from Picardy, not Scotland, and was called Toom Tabard, or Empty Jacket, by his contemporaries. Edward reasoned that his bloodline made him an acceptable king and that John’s pliant nature would work to England’s advantage.

After the coronation of the new king, Edward made it abundantly clear to the nobles that it was he and England that controlled their futures. King John dutifully traveled south to England to swear fealty to Edward while the English monarch absconded with the seal of Scotland, had it broken into four pieces, and then placed it in the treasury of England, giving due notice to all of the political reality.

Although owing his elevation to kingship to Edward, John de Baliol soon realized that his new relationship with England was a disaster for Scotland. Edward called him repeatedly to England, finally telling him that Scottish troops were expected to fill the ranks of the English armies preparing for the seemingly annual invasion of France. The Scottish King could only acquiesce in the presence of Edward, but once back in Scotland, his nobles not only rejected Edward’s demand for troops, they went so far as to expel English officials and refused to recognize English ownership of Scottish fiefs.

A Short-Sighted Invasion by the Scots

This was bad enough and certainly would have provoked an English response in time, but the Scottish leaders pushed their king to do even more. In 1295, de Baliol renounced the homage he swore to Edward and declared for, and received an alliance with, England’s sworn enemy, Philip the Fair, King of France.

Not willing to wait and allow Edward to get the upper hand, the Scots conducted a swift but poorly planned invasion of northern England that was repulsed. Edward, incensed by the rebellion and betrayal, put the invasion of France on hold and prepared to deal with the Scots.

In 1296, Edward’s army crossed into Scotland, beginning a series of wars that would last well into the 16th century. After defeating the Scots army at Dunbar Castle, Edward marched north to the Scottish capital of Edinburgh. Taking the city, he proceeded to Montrose, where John de Baliol surrendered. Edward had him sent south to imprisonment in the Tower of London.

The English monarch also took the Lia Fail, or the Stone of Destiny, upon which Scottish kings had been crowned, removing it to Westminster Abbey, after he had himself crowned upon it. Edward felt that by this act, he had psychologically denied the Scots any chance of legitimately crowning a king without English assent.

But the Scots did not give up their fight for independence. After the capture and imprisonment of John, a new leader arose to lead the nation, the brave and resourceful William Wallace.

Described in the Scotichronicon as being “a tall man with the body of a giant, cheerful in appearance with agreeable features … but with a wild look … by his appearance alone he won over to himself the grace and favour of the hearts of all loyal Scots. [He was] a distinguished speaker, who above all else hunted down falsehood and deceit and detested treachery.… He lay in wait for thieves and robbers, inflicting rigorous justice on them. Because God was very greatly pleased with works of justice of this kind, He in consequence guided all his activities.”

Wallace’s rebellion lasted less than a year, with fortunes riding high after a brilliant victory over England’s northern army under command of John de Warenne and Hugh Cressingham at Stirling Bridge in September of 1297. The English failed to take the threat of Wallace’s rebellion seriously and paid for this in the destruction of their army.

The Tragic Fate of William Wallace

In July of 1298, the Scots faced Edward I, and the struggle had a very different outcome. The Battle of Falkirk was the undoing of the rebellion. The Scots were decisively defeated, but Wallace continued a guerrilla war against the English until betrayed in 1305. He was then taken to London and “tried” for treason. His sentence, graphically portrayed in the film Braveheart, was carried out and his head was placed in prominent view for all to see as a deterrent to further rebellion.

Edward, unwilling to take a chance on another Scottish “king” from any of the factional noble Scottish families, this time chose two regents, John Comyn and Robert the Bruce, who would act as rulers over the Scots. This was a disastrous move, because both families felt they had a legitimate right to rule as kings. The Bruces had a direct link to the crown through, again, William the Lion. The Comyns likewise felt they had the right to rule. It was only a matter of time before the two families would fall out over this.

Like many Scottish nobles, the Bruce family owned lands in England as well as in Scotland. Of Norman lineage, the two centuries since the Conquest of England in 1066 found the Bruce family well settled and accepted by the people as Scottish nobles, not English ones. But the Bruce family had prospered by remaining loyal to the English during the rebellions, and had been amply rewarded for this loyalty. It had been one of the 12 factions vying for power after the death of Alexander III, but had remained on the side of Edward against Wallace, participating in the slaughter of the Scottish army at Falkirk. In choosing this loyal family to keep the Scots peaceful, Edward did not figure on the death of the elder Robert the Bruce or the character of his son, Robert the Bruce the younger.

With the death of his father in 1304, the 30-year-old Robert inherited the family estates in England and Scotland. Robert reportedly possessed a fierce temper as well as a powerfully motivated patriotic streak that Edward did not detect when he granted him the elder Bruce’s offices. Not content to watch destiny pass him by, Robert, unlike his previous family members, dedicated himself to Scottish independence.

Robert began his climb to power by brutally killing his co-guardian, John Comyn, on the altar of a church during a heated argument in February 1306. The family feud that had been frothing for decades finally ended.

Realizing that Edward would have nothing less than his head for the murder of an appointed ruler of Scotland, Robert Bruce took immediate steps to take control of the country. He appealed to the Scots’ rebellious nature and was duly crowned Robert I at Scone on March 25, 1306, following Scottish tradition, and engineered an absolution from the Bishop of Glasgow for the killing of Comyn. He was acclaimed by the rancorous Scots who were eager to return to battle and regain their freedom from England.

For the next eight years, fierce and bloody battles raged across the border between Scotland and England. Robert lost two early battles, but later defeated three thousand English at Loudon Hill with only a thousand men of his own, six hundred of them pikemen, whom the English foolishly charged with cavalry. Throughout this period, Robert employed guerrilla tactics, allowing his outnumbered, poorly armed forces to continually hurt the English.

Edward’s Gentle Successor

He barely survived the brutal English retaliation, which swept up and hanged three of his four brothers. In addition, Edward put Robert’s sister and daughter on display in iron cages. The English King carried a hatred for Robert for the remainder of his life, until he died in 1307. The death of Longshanks was little comfort to these victims of the savage war.

Edward II has been variously described as “gentle, indolent, unwarlike, with no stomach for hard fighting,” or “… weak, pleasure loving and worthless,” a far cry from his father. The new king attempted to continue his father’s policies, sending armies into Scotland in 1310 and 1312, but his armed might could not prevent the Scots from launching retaliatory raids into northern England.

As the war dragged on, Robert the Bruce’s guerrilla war strategy began to wear down the English. Their armies simply could not remain continually in Scotland. It was expensive to launch a military expedition, and as the years passed, Scottish bands laid siege to English strongholds in Scotland, legacies of Norman times, and the outnumbered and isolated garrisons were forced, one by one, to submit to the surrounding enemy forces.

By the spring of 1313, only three major strongholds in Scotland remained in English hands, one being Stirling Castle. The commander of the garrison, Sir Philip Mowbray, a Scot who had thus far remained loyal to England, held out against a spirited siege by Robert’s surviving brother, Edward Bruce. Edward has been described as a cavalry leader, one who was comfortable with a war of mobility rather than one of siege work. Thinking that he would enable his army to capture the fortress without a protracted, bloody fight, Edward approached Mowbray with a proposal. Simply stated, if the castle was not relieved by June of the next year, it would be surrendered. If relief did come, the Scots would give up the siege and leave. Mowbray, seeing his chance to avoid certain eventual defeat, readily agreed.

Upon hearing of the terms offered, Robert could not believe his brother had made such an arrangement with the enemy, saying to him, as Barbour wrote half a century after the battle, “That was indeed unwisely done. We are so few against so many. God may deal us our destiny right well but we are set in jeopardy to lose or win all at one throw,” a brotherly understatement. Edward tried to explain to Robert that they would have to fight the English sooner or later, why not at a time and place of their own choosing? Robert, reluctant to acknowledge a direct invitation of an English invasion as any form of diplomatic victory, continued to think of his brother as foolish, but planned for the expected response as best he could.

Edward II received word of the agreement and knew that he could not sit by and let Stirling fall. He also could not let the blatant challenge from the Scots go unanswered. In the early spring of 1314, he began to make plans for a full-scale land and sea expedition against Scotland.

Edward Assembles an Army 20,000 Strong

Edward did not possess the imposing personality of his father. Writs were initially sent to 93 barons of the realm, ordering them to assemble with their retainers at Newcastle, where they would be joined by three thousand Welsh archers and hundreds of mercenaries from the continent. But the response was so poor Edward was forced to send a second summons, this time more specific and asking for 21,000 men. As he traveled north in May, he could not believe that four of his most powerful English earls had not even bothered to appear. He issued a third summons, this one leaving no doubt about the expected response, “You are to exasperate and hurry up, and compel your men to come,” he wrote. This time, all of the summoned nobles responded and Edward found himself with an army of over 20,000, plus a cumbersome baggage train 20 miles long.

The mainstay of the English invasion force was the mounted knight, various sources giving exceptionally disparate figures, but probably there were around 500 of them along with 1,500 or so mounted retainers. These troops were expensively equipped with the best armor of the day and mounted on hardy, strong Flemish chargers, or destriers, as they were called. Uncontrollable at times, these warriors were deadly against poorly organized and thinly armored opponents.

Augmenting this powerful armored force were the thousands of Welsh archers. The bowmen could slaughter a Scots field army in less than half an hour if properly supported and allowed to fire at close range into closely packed ranks of enemy spearmen, who would be helpless to respond. Utilizing the soon-to-be-famous longbow of Crecy and Agincourt fame, these missile troops were brought along to harass the Scots and provide the cavalry with a second offensive arm.

The bulk of the English army consisted of thousands of foot, brought along by the various nobles who joined the expedition as well as a number of Scots fighting for Edward II against their countrymen. Of this Edward II invasion force of the spring of 1314, Barbour wrote: “French knights, valiant men of Gascony and Germany, men from the Duchy and from Brittany … from Wales also, and from Ireland … from Poitiers, Aquitaine, and Bayonne.… And from Scotland, besides, he had a great following of might.”

The Scots had plenty of time to prepare for the expected invasion and Robert Bruce used this time well. Although he could scarcely assemble an army a quarter of the size of the English host, he took what troops he had and drilled them from March to June.

The Scots Possessed Brave and Charismatic Leadership

Robert’s five to six thousand Scottish foot, many “ragged and often shoeless,” were augmented by five hundred cavalry who were much lighter armored than their English counterparts. Thousands of camp followers, called “small folk” by Barbour and others, also marched with the Scots army, but these were ill-armed, undisciplined, and of dubious military value. The advantage the Scots did have was in the quality of their charismatic leadership. Robert had endured the privations of his men, fighting alongside them and leading them personally into battle.

Besides Robert, there was the famous Black Douglas, a fearsome warrior; Randolph, Earl of Moray; Keith Marischal, commander of the cavalry; and Edward Bruce. These were brave fighters who had battled for many years against the hated English Sassenach.

The Scots also had the advantage of position. Robert knew the route Edward would have to take to reach Stirling. He picked his battlefield and carefully prepared it.

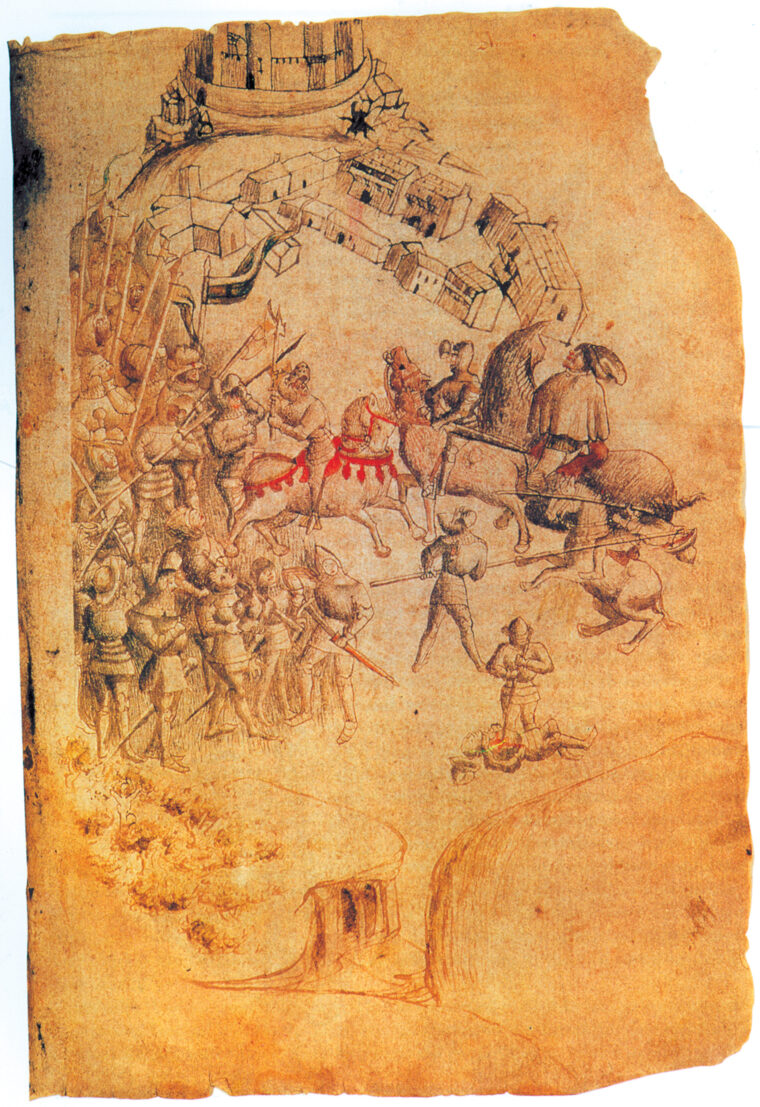

Edward moved confidently north, as the Vita Edwardi Secundi informs us: “The king, in his confidence, hastened day by day towards his goal. Short time was allotted for sleep, shorter for meals.” Robert, meanwhile, had his forces assemble in the Torwood forest, across the road from Stirling. His army was formed up, but in readiness to fall back to Bannockburn, which they did upon sighting the English army.

Three miles south of Stirling Castle flowed the Bannockburn, a stream with high banks covered with thick, dense brush that prevented crossing other than at the ford where the road approaching the castle bisected it. After crossing the stream, a traveler would have to move up a slight slope, topped by a wooded plateau two miles from the castle walls.

To the east of the plateau was a boggy area, known as the Carse, where movement would be difficult for cavalry. West of the road was a woods, covering a large portion of the gentle slope. It was a defensible position with both high ground and a limited area for the English cavalry to maneuver. It also had forests into which the Scots could retreat if defeated. In this area Robert Bruce chose to make his stand. It contained all of the elements of his ideal ground: woods to the rear, uphill of the enemy, and boggy ground to break up the English cavalry attacks.

Because the English garrison in Stirling could not be expected to sit idly by and watch the upcoming battle, Robert had his men cut trees and block the forest trails, leaving guards to report any surprise flank or rear attacks from either the castle garrison or Edward’s cavalry. Besides this, on the front slope of the hill, Robert “caused many pits to be dug, of a foot’s breadth and the depth of a man’s knee … and he covered them with sticks and green grass, that they may not be easily seen,” Barbour reported.

Both Sides Prepare for Battle

There were also reports by a participant in the battle, Robert Baston (an English friar captured by the Scots), that the Scots employed “a device full of woe … formed for the horse’s feet, hollow, with spikes, that they may not pass without fall. The commons dig ditches that on them the cavalry may trip.” Baston mentioned that the pits were dug on either side of the road, where the English army was expected to appear. The “spikes” probably were a form of caltrop, a device with four pointed ends that could be scattered across a field to cripple cavalry.

Once these preparations were completed Robert sent the “small folk” to a sheltered area in the woods where they would be out of the way. He then deployed his army.

The various contemporary and near-contemporary sources, as well as almost every modern text dealing with the Battle of Bannockburn, disagree on numbers, types of fighters, and just about everything else dealing with the Scots in the battle, even down to where they actually fought. I have synthesized the available information and come up with the following order of battle for the Scottish army.

Robert took advantage of his superior tactical position. The main division, made up of two thousand Highlanders, lowland spearmen, and descendants of the Norsemen, the Scots Islemen, he placed astride the medieval road (in some sources called the “Roman road”) under his direct command. Edward Bruce he stationed directly behind his own division with a thousand lowlanders and Galwegians hidden in the woods, but in close support. Randolph’s 500 to 750 lowland spearmen he placed at St. Ninian’s Church, a half-mile to the rear of his own and Edward Bruce’s division, in order to guard against an attack from Stirling Castle.

Robert arrayed Douglas’s thousand men between Edward Bruce’s division and Randolph’s, and he placed Sir Robert Keith’s 500 Scottish cavalry and a few hundred Scots archers to the rear of the main army in reserve. Once the troops were in their positions, Douglas and Sir Robert Keith set out with a handful of scouts to check on the English army while the rest of the troops rested.

The English army began marching early on the morning of June 23, 1314 and had covered over 20 miles when they were sighted by the Scottish scouts. The Scots were initially astounded when they caught sight of the English covering the road to the horizon. The numerous standards of England, France, Brittany, Poitou, and even Germany flapped in the warming afternoon breeze. Word soon spread that surely the English King had gathered an unbeatable army. Edward had brought fully 10 divisions to break the siege of Stirling. As Douglas and Keith returned with their men to Robert’s position, they were filled with alarm.

We Will Win or We Will Die

Robert told his commanders to remain quiet about the numbers of the enemy, but knew that his army could not help but see the endless column of Englishmen and their allies marching toward them. With a wave of his arm, Robert quieted his murmuring troops and told them that the Sassenach might be numerous but that they were tired and disordered as well. He then told them that any Scot with a faint heart should leave immediately. The ranks of spear and axe-armed foot shouted back that they would win or die.

As Edward’s vanguard neared the ford over the Bannockburn, a surprise arrived in the person of Sir Philip Mowbray, commander of Stirling Castle. He and a body of troops had ridden around the Scottish army by passing far to the west of their positions. He brought valuable information about the Scots preparations and observed positions, having spied them from the towers of the castle. He also told Edward that he now considered himself and the siege relieved by the English and therefore did not have to surrender.

Edward decided that even though his army was scattered along the road for 20 miles, he would not waste a moment and immediately planned for an attack. First he ordered Lords Clifford and Beaumont to take their best knights and ride east of the Scottish positions and circle around to Stirling, thus effecting the actual relief of the castle. Edward planned to have these troops gather together with Mowbray’s garrison and attack the rear of the Scottish positions.

Meanwhile, the King’s nephew, the Earl of Gloucester, along with the Earl of Hereford, would ford the Bannockburn and force the Scots on the slopes above to retire, effectively clearing the field and trapping them in the woods.

As the first English knights crossed the ford, they sighted the Scots falling back into the woods on the slope before them. No doubt Robert wanted to tempt them into a precipitous charge, so that they would be disordered by the pits and caltrops. Once the cavalry charge was broken, the Scottish foot could charge down on them and deal with the cavalry.

TheVitatells us what happened next. Henry de Bohun with some Welsh troops pursued the retiring Scots to the woods’ edge, hoping to find Bruce there and kill or capture him. Suddenly, Bruce appeared out of the woods and Henry, seeing the Scots in great numbers, turned his horse. He had found his enemy. Robert was easily distinguishable by the gold crown adorning his helmet. With a fierce cry, Henry lowered his lance and rode toward Robert, expecting to win everlasting fame and honor for killing the Scottish King in single combat.

At first, Robert did not move, and his troops watched in growing alarm as the armored Englishman bore down upon their king. As de Bohun came up the slope, however, Robert began to move toward him slowly. It cannot be discounted that the Scottish King had the advantage of being uphill of his enemy. It is much more difficult to charge up a gentle slope than down it and de Bohun’s heavy Flemish mount would be tiring rapidly.

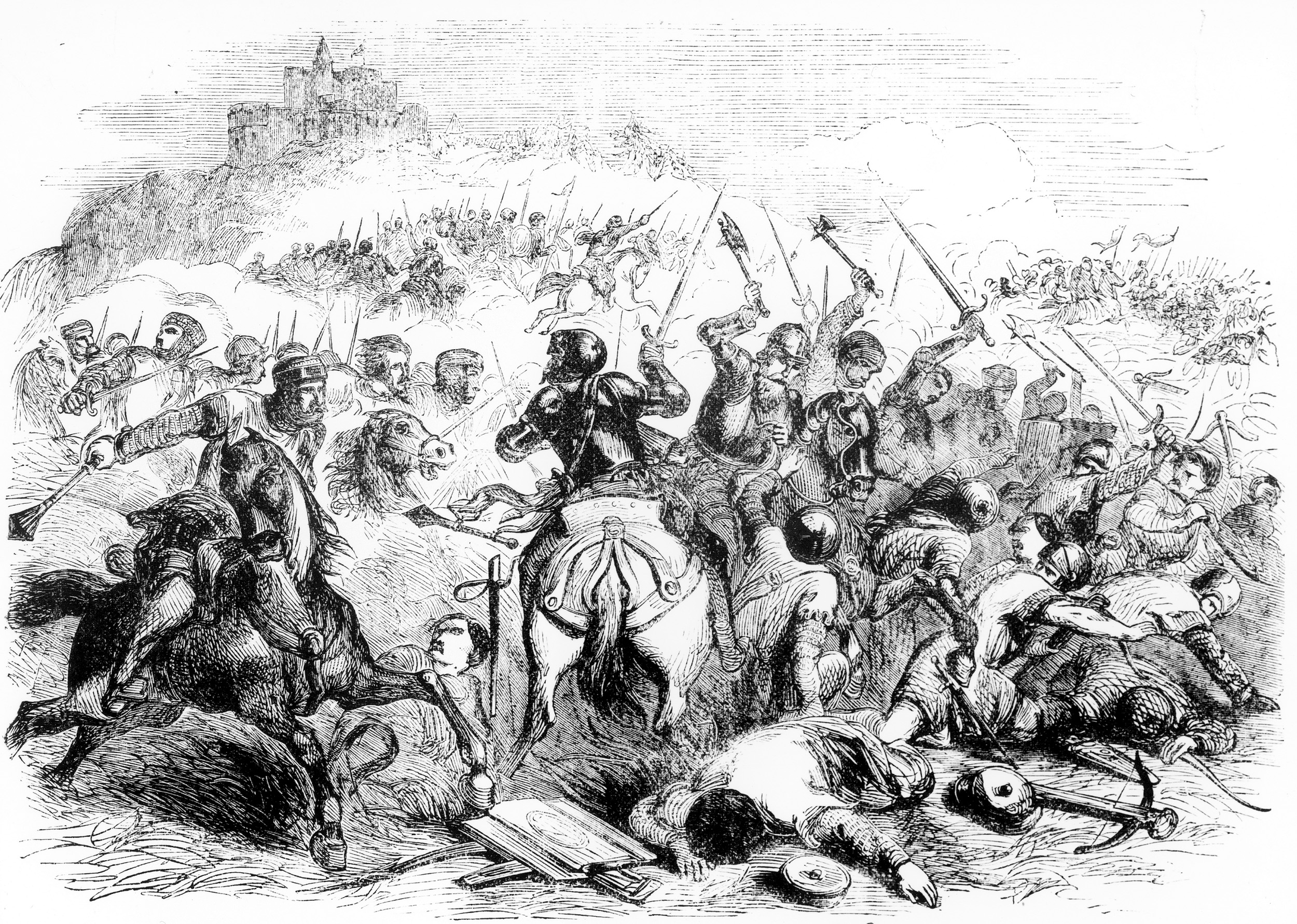

“Bruce Broke his Head Open with an Axe”

De Bohun, confident of his superiority over Robert owing to his heavier armor and larger horse, must have been extremely surprised when Robert deftly moved his smaller, more manageable horse to the right of the Flemish charger, causing the deadly lance to pass harmlessly by. Then, very swiftly, Robert stood up in his stirrups and swung his axe with all of his strength down upon de Bohun’s helmet. TheVitanoted that “Bruce broke his [de Bohun’s] head open with an axe.” Barbour wrote that the axe broke in two pieces, leaving the axehead in de Bohun’s skull.

As the dead de Bohun toppled from his horse, Robert reportedly complained that he had ruined his axe, amid the cheering of his men. The English vanguard, shocked by the loss of an illustrious and famous fighter in such dramatic and brutal fashion, halted its attack. The Scots quickly took advantage of the confusion and frustration of the English, and the Highlanders and Islemen charged out of the woods and downhill at the groups of Englishmen milling near the ford. The wild Scotsmen, their battle fever up, swept ahead, killing numerous Englishmen as they fled back across the stream.

A few of the knights found the pits in this way, as they fled to escape the jubilant Scots, and fell to their deaths beneath the blades of Robert’s pursuers. Through sheer strength of personality, Robert kept his men from following the English over the Bannockburn. They obeyed his orders and returned to the higher ground.

As he returned to his own ranks, Robert was heartily admonished for facing the heavier armored enemy alone. Looking up at the castle looming in the background, Robert noticed the glint of metal and a large amount of dust passing his left flank.

These were the knights sent by Edward to Stirling Castle. At first Robert was angered that Randolph Earl of Moray had not detected this force riding past his post, exclaiming to him that “a rose has fallen from your chaplet,” but the Lanercost Chronicle, dated from 1346, noted that Moray had indeed seen the English knights and had allowed them to outstrip their supports before attacking them. This is corroborated by Sir Thomas Gray (whose father had been captured and made prisoner by the Scots during the battle). He wrote that “meanwhile Robert Lord Clifford and Henry Beaumont with 300 men-at-arms rode round the wood … [while] Moray … [a] nephew of Bruce … had heard that his uncle had driven back the English on the other side.… [He] issued from the wood.”

Moray’s men raced down to the road where the English were riding, formed across the road into the familiar schiltron, or circle of spears, sand waited. Beaumont, seeing the Scots formed up on the road ahead, suggested that they simply ride around the spearmen, saying, “Let us halt a little, let them come on; give them room,” and thus allow the English to simply go past them. Thomas Gray, the eyewitness, looking at the Scots position, said to Beaumont that no matter what the English did, the Scots would have the superior position, to which Beaumont replied, “If you are afraid be off.” Thomas Gray, his honor and bravery questioned, lowered his lance and charged into the blocking body of five hundred Scotsmen. He fell and became a prisoner. Others were not so lucky.

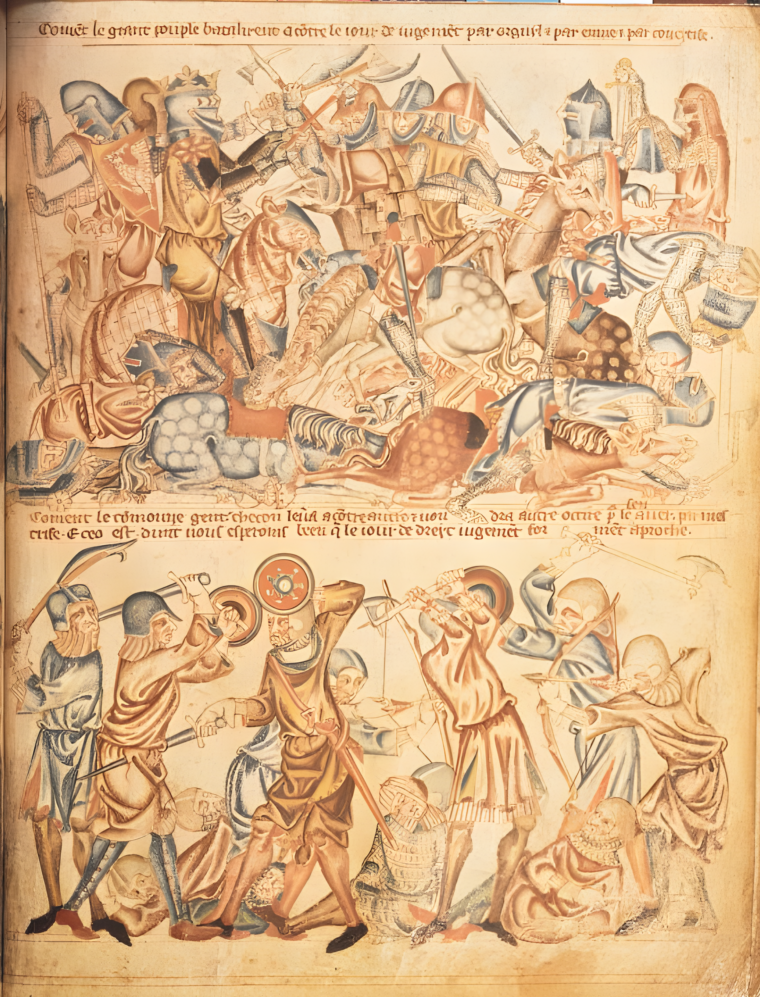

The Finest Knights in England Crashed Against the Wall of Spears

With a cry, the rest of the English charged into the spearmen. Horses and riders fell beneath the long spears, the riders then being trampled beneath the hoofs of their comrades behind them. The Scots recoiled but held. Again and again the finest knights in England tried to smash through the wall of spears. A few knights rode into the mass of Lowlanders but could not effect a crack in the shieldwall. The English earls soon regretted not having brought a few hundred Welsh archers with them; they would have been able to shoot the schiltron to pieces.

The heat of the afternoon soon wearied the horses and fatigued the sweating knights who took to throwing their lances, swords, maces, and other objects at the unbroken Scots. On the slopes above, Black Douglas twice asked Robert Bruce for permission to go to the aid of Moray’s tiring spearmen. Robert refused, saying to Douglas, “The Earl of Moray has gained the day and since we were not there to help him in the battle let us leave to him the credit for the victory.”

Finally, seeing the horsemen wavering, Robert gave the order to advance but not to charge, and a thousand fresh Scots descended the wooded slope toward the sound of battle.

All the English knights needed after over an hour of thirsty, exhausting, and fruitless battle was to see a thousand more Scots spearmen attentively standing a hundred yards off their left flank, apparently ready to charge at any moment. Moray, seeing the indecision and fear in the eyes of his tormentors, ordered his spearmen to break their protective formation and charge the cavalry!

Not used to being charged by lowly foot with long spears and screaming for blood, the English knights turned and ran, some toward Stirling Castle, the rest back to Edward’s standard. The Scots could not catch the horsemen, so they sat for a while, resting and looting the corpses of their enemies before marching back uphill to join the main army.

Edward, deeply disappointed that his troops had not been able to break through in force to Stirling, ordered his exhausted army, having marched all day, to set up camp and finish the battle the next day. Although weary, different sources give divergent scenarios of what it was like in the English encampment the night after the first day’s battle.

The English crossed the ford and turned right, following the Bannockburn until they reached level ground, where water and firewood were available. Above the encampment, the slope gently rose—good cavalry ground and one not covered with pits. For the morrow, Edward planned on shooting the Scots army to pieces before sending his knights into battle to complete the rout.

For his part, Robert Bruce had no illusions about his victory. A small number of English knights had been killed, but other than that, the enemy army remained intact. The next day, the English would simply come up the hill, shoot his foot to pieces, and ride down the survivors. Robert had almost decided to retreat under cover of darkness, until an informant brought him word of the poor condition of Edward’s army.

“If You Ever Intend to Reconquer Scotland, Now is the Time”

A knight, Sir Robert Seton, who had marched north with the English army, made his way to Robert’s circle and informed him: “Sir, if you ever intend to reconquer Scotland now is the time. The English have lost heart and are discouraged,” making a pledge on his life that if Robert stayed and fought, he would win the battle.

How bad was English morale? According to Gray, the English army spent the night on “a plain towards waters of the Forth beyond Bannockburn, a bad and deep watery marsh,” hardly a comfortable position in which to get a needed night’s rest. TheVitaconfirms this, stating that “there was no rest or sleep, for men expected the Scots to make a night attack,” while Lanercost concurs, noting, “thus fear fell upon the English and the Scots were encouraged.” Describing talk among the troops themselves, Lanercost has them questioning their ability to win: “[When] our lords wage war unrighteously, God is offended and brings misfortune and so it may happen now.”

A very different conclusion was made by Baston, who wrote that “while they thus boast with wine in the night reveling.… They sleep, they snore.”

Robert called his commanders together and roused them with a speech vilifying the English and praising the nobility of the Scots. He then made it clear that he meant to exalt the next day’s victory as Papal edicts had done with the Crusaders taking the cross. “Our royal power decrees that all offenses committed against us are pardoned for those who now defend [our] ancestral kingdom well.” This extraordinary proclamation found Robert taking for himself the right and privilege of the Pope to declare a remission of sins for his followers. He then made a more base appeal to greed, while making sure everyone understood that looting was to be reserved until after the battle had been won.

The Scots commanders then went over their plan of battle for the next day. Moray’s victory over the English knights gave Robert the inspiration to plan an assault on the much larger English force. The English army had settled in an area where there was no room to maneuver their large number of troops around the Scottish flanks. For all their numbers, only a limited amount of men could physically occupy the level ground between the Scots position and their own. Robert also had full confidence in his generals and the high morale of victorious troops. He had one other benefit. The English still had no idea of his actual strength.

At dawn on June 24, the Scottish army arose and ate lightly, their priests walking among them and celebrating Mass. The divisions were then formed and the troops gathered together under their commanders where they heard the repeated words spoken by their king the evening before. Robert then called forth those who had proved most brave the day before and knighted them on the field in front of their countrymen. He then gave the order to advance.

“They Ask for Mercy, But Not From You”

Robert’s division formed up in the woods on the top slope of the plateau, out of sight of the English sentries. The rest of the army consisted of Black Douglas’s division on the left flank, Randolph of Moray’s in the center, and Edward Bruce’s on the right. With a cry, these three divisions poured out of the woods with banners flying and marched toward the English camp in an echeloned line.

It did not take long for English sentries to alert their camp, and the awakened invaders could not believe their eyes as thousands of Scots “farmers” moved down toward them. Edward, apparently stunned into inaction and shouting “What, will yonder Scots fight,” allowed the Scots to get to within a hundred yards of his army before calling them to arms. Although initially shaken by the audacity of the Scots foot, Edward was encouraged by their paucity in numbers. When the advancing ranks suddenly halted and fell to their knees in prayer, the English King cried, “Yon folk are kneeling to ask for mercy!” to which a Scots nobleman in English employ answered, “They ask for mercy, but not from you … [They] will win all, or die.”

The disordered and congested English line began to move toward the Scots in three large divisions of three lines each, knights in front supported by foot behind. The result of this confusion was that the thousands of Welsh archers could not see to shoot, and those that did fire had as good a chance at hitting their allies as their enemies. Barbour noted that the archers had actually started to move off ahead of the English knights and, after driving off the few Scots archers in the center, had moved out of the way to the English flank.

The English commanders were anything but in concert as to what to do. Gloucester, desiring to rest the army after its forced marches, had been roundly criticized as being disloyal. In apparent fury, he charged ahead of his command onto the waiting spears of the Scots. The Vita describes his attack against the division of Edward Bruce: “[Gloucester] would have been victorious if his men had been faithful. But as the Scots charged home, his horse was killed and he fell … [He had] dashed forward to have the glory, and thus was unsupported and killed.”

Not to be outdone, dozens of other knights and nobles broke ranks and charged pell-mell to their deaths alongside him. The Lanercost Chronicle describes the effect of knights meeting the spearmen: “When the shock of battle came and the great horses of the English dashed upon the Scottish spears as upon a great forest, there arose a great and horrible din from the broken lances and the wounded horses.”

Seeing the English concentrating on these fruitless attacks on the most advanced schiltron, that of Edward Bruce on the Scottish right flank, Moray moved his division past Edward’s and proceeded to overwhelm the exposed flanks of the English cavalry. Douglas also brought his division up until all three Scots schiltrons presented an unbroken front to the English second line, preparing to charge in.

British Archers Cut to Pieces

An English commander managed to shift several hundred archers to the northern rim of the gorge where they began to fire into the close-packed ranks of Douglas’s division. For some reason, no one thought to provide the archers with a reserve of cavalry to protect them from attack. Robert, seeing the danger and noting no supports, ordered Sir Robert Keith’s five hundred cavalry to attack the archers. Barbour wrote, “[He] rode among them so forcefully, spearing them so relentlessly, knocking them down and slaying them in such numbers without mercy, that one and all they scattered.”

The archers were cut to pieces; those that could tried to run to the protection of the main army, crashing into their already congested comrades, further disrupting them and causing not a few of their allies to turn on them and cut them down for running away while others joined their flight.

With a shout, the three Scots divisions once more began to roll downhill, narrowing the front so that the English became crowded together. The spearmen hit the English cavalry at the run, and it was at this point that Robert Bruce led his own large division charging out of the woods and downhill against the English, whose rear ranks were pushing into the milling front ones, slowly falling apart in the face of the savage Scottish attack.

Edward II then ordered his knights to renew their charges against the Scots, but they did so in a disordered state, effecting no real advantage. In fact, Moray’s and Douglas’s divisions simply pushed the cavalry back with their unbroken, bristling line of spears. As the English ranks further contracted, Robert Bruce’s men hit them at the run, causing even more turmoil.

The battle now settled into the bloody hand-to-hand melee of medieval warfare. Barbour wrote, “There was such a din of blows, [such] as weapons landing on armour, such a great breaking of spears, such pressure and such pushing, such snarling and groaning.”

Many of the English foot began to run left into the gorge to escape the screaming Scots. More and more joined in, flooding the depression with men, stumbling and falling, foot, knights and noble alike, all intermingled in a mass panic as the Scots followed them with cries of “Press on, they fail.”

Edward Forced to Flee by His Guard

Still, the English King had his personal retinue intact, five hundred strong, and was about to order a new attack. But just then yet another, even larger Scottish division began to stream down the hill, banners flying. Whether planned or spontaneous, the Scottish camp followers had affixed cloth to limbs of trees and, as Barbour wrote, “all together they gave a cry, ‘Kill! Kill! On them now!” and charged downhill toward the remaining faltering English.

Edward refused to run, but his guards took the reins of his charger and led him from the battlefield. He and his men had to cut their way through the encircling Scots as they attempted to drag him from his horse. Finally, however, the entourage broke through and rode to Stirling Castle. But Mowbray refused them entry. He told the King he would be honor-bound to surrender him along with the castle when the Scots arrived. Edward continued his headlong flight.

The English cavalry mostly managed to ride to safety, easily outdistancing the Scottish foot, though a few hundred knights were captured and held for ransom. Fordun, writing in 1384-85, noted that “nobles were taken, for whose ransom not only were the Queen [of Scotland] and other Scottish prisoners released from their dungeons, but even the Scots themselves were, all and sundry, enriched very much. From that day forward … the whole land of Scotland not only always rejoiced in victory over the English, but also overflowed with boundless wealth.”

The Aftermath

Over three hundred barons, knights, and other nobles lay dead on the field of Bannockburn along with uncounted numbers of English foot. Most of the surviving Welsh archers outdistanced pursuit and were not rallied until reaching Carlisle, a hundred miles away. Others were not so lucky. For days after the battle, fugitives were stalked and killed by the Scots, eager to avenge past defeats. The English field army, smashed and routed beyond recall, no longer was a deterrent to the Scots. As the Vita Edwardi Secundi bluntly put it, “So many fine noblemen and valiant youths, so many noble horses, so much military equipment … all lost in one unfortunate day—one fleeting hour.”

The consequences of the battle were several. Mowbray wisely changed sides and became an ally of Robert Bruce. He surrendered Stirling Castle, and the Scots tore it apart stone by stone as a hated symbol of English oppression.

Edward Bruce, a potential rival to his brother, soon went on a military adventure to Ireland in order to deprive England of its valuable source of recruits and war supplies. After a briefly successful campaign, he took the Irish crown for himself, but fell beneath English lances at the disastrous Battle of Fauqhart in 1318.

Edward II survived his defeat only to be murdered in 1327.

Robert the Bruce outlived his old antagonist by only two years.

The Battle of Bannockburn not only delayed the eventual English military conquest of Scotland, but also demonstrated to discerning English tacticians the value of combined-arms combat, notably the use of steady, spear-armed foot with mobile cavalry reserves. Edward II’s grandson, Edward III, would refine the tactics of Robert the Bruce by adding thousands of archers, to the regret of the French who would fall to this deadly combination at the Battle of Crécy 32 years later.

Join The Conversation

Comments