By Al Hemingway

By 1945, the war in Europe was nearing its conclusion. Having suffered a severe defeat at the hands of the Allies in the Battle of the Bulge, Adolf Hitler’s seemingly indestructible Third Reich was quickly crumbling under the Allied juggernaut. With British and American forces closing in from the west and the Soviets moving rapidly from the east, the Nazis decided to shuffle Allied prisoners of war from their prisons to avoid repatriation by friendly forces.

Most POWs were hurried from their camps with nothing more than the clothes on their backs. With the temperature well below freezing and, in some areas, more than a foot of snow on the ground, the Germans herded the men like cattle. The ensuing death march, also known as the “Shoe Leather Express,” or the “March to Nowhere,” resulted in the deaths of many POWs, but with the surrender of Nazi Germany in May 1945, it would soon be forgotten. Most POWs helped each other through the horrible ordeal. Steve Stupak of Watertown, Connecticut, survived the arduous trek with the assistance of his fellow camp inmates. A member of the 331st Squadron, 94th Bomb Group, Eighth Air Force, Stupak was taken prisoner when his Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress bomber was shot down on October 7, 1944. In an interview with Al Hemingway, Stupak recalled those terrible days that he miraculously survived more than six decades ago.

Al Hemingway: Where were you born?

Steve Stupak: I was born in Lopev, Pennsylvania, on June 8, 1920. As a young child I moved to Dupont. I attended grade school and, because Dupont was so small we didn’t have our own high school, I went to nearby Avoca High School. I grew up during the Depression, and things were rough so I didn’t graduate. I had to work.

AH: What kind of work did you do?

SS: I got a job with the National Youth Organization working for the State of Pennsylvania doing gypsy moth control. It was a 40-hour week, and we grossed $20. Because I was in the Boy Scouts, I learned how to read maps. I would tell my boss where we were located, and he made me second in command. That was great because my pay doubled. I thought I was a millionaire!

AH: Quite a bit of money at that time.

SS: You bet it was. When that job ended, I had enough money saved to go to New Jersey. Pennsylvania was pretty depressed at that time. I went to work for a department store operating a steam table in their luncheonette area and was paid a dollar a day. I was just breaking even, so I started looking for another job. I got a letter of recommendation from a guy at the unemployment office, and he told me to go to the Western Electric plant. There must have been 200 people in line and the guard was yelling, “Go home; we have no more openings today!” I managed to work my way to the front and handed him the letter. The guard took it and he came back and opened the gate and told me to come in. He took me to see the boss, who gave me a job making telephone jacks for switchboards.

AH: You were lucky.

SS: I had to work the midnight shift, but I didn’t mind. The work wasn’t hard. In fact, I could have gone to work with a shirt and tie on. I wasn’t complaining. One weekend I went to Scranton to visit my mother, and my brother was there from Cleveland, Ohio. He talked me into going to Cleveland to get a job. So I did. I wasn’t there three months, and Pearl Harbor was bombed on December 7, 1941. They were closing the place where I was working and turning it into a government plant for the war effort. So, I knew I’d be called up in the draft and I decided to enlist.

AH: When was this?

SS: This was January 1942, and I enlisted in the U.S. Army Air Corps. There was no Air Force in those days.

AH: Why the Air Corps?

SS: When I was a kid in Pennsylvania, I knew a guy who flew, and he told us of his exploits. It was adventurous, and it captured my imagination. I was sent to Maryland to get inducted, and from there we went by train to Jefferson Barracks, Missouri. It was an old cavalry outpost, and it was cold there. They had to set up tents—there were so many of us. But I lucked out and got assigned to one of the buildings.

AH: What was your basic training like?

SS: It wasn’t too bad. In addition to the normal training, we watched a lot of propaganda films about Germany and Japan. We remained there until the end of February, and then we went to Bakersfield, California. The Army had a training school there and an airfield.

AH: What kind of aircraft did you train on?

SS: It was a BT-6. The BT stood for basic training. It resembled a P-47 Thunderbolt [fighter]. Since I was a small guy, I always seemed to be in the fuselage to check the wiring and other controls. After training, we were assigned to Santa Ana, California. It was a replacement squadron for everyone going overseas. It was so big they had three bus lines for soldiers reporting in and 14 mess halls! The place was enormous.

AH: With the influx of cadets for the war, it must have been a huge operation. What next?

SS: Originally we were slated to be permanent personnel. We were going to be the training cadre for the new recruits. Well, I wanted to go overseas, so I saw a notice asking for volunteers for gunnery school. I applied, but my first sergeant and I never got along. So to get even with me, he pigeonholed my orders. That is, he squashed them.

AH: That’s too bad. What rank were you then?

SS: I was a sergeant by then.

AH: Wow, very good indeed.

SS: Well there was a war on, so they needed us.

AH: What ever happened to that first sergeant?

SS: He got into some trouble, and he was transferred. We got a new commanding officer, a captain who was related to Rosalind Russell. Anyway, he saw to it that my orders to gunnery school were processed, and I was gone in a week. I traveled to Amarillo, Texas, for armament school to learn all about the weapons on the B-17 bomber. Classes were held 24 hours a day, seven days a week. After graduation, I was shipped to Kingman, Arizona—the worst place God ever created [by war’s end, 36,000 personnel had been trained as aerial gunners at Kingman].

AH: I’m assuming the heat?

SS: Yes, it was awful. They did air condition the buildings.

AH: That was unusual for that time.

SS: First of all, it wasn’t for our comfort. It was the equipment they were concerned about. Also, the air conditioners were set at 85 degrees, so it was still very hot. They couldn’t get it any cooler than that. Daytime temperatures were well over 100 degrees. They also issued us mosquito netting.

AH: Mosquito netting? In the dry Arizona climate?

SS: Not for mosquitoes. It was for the scorpions. At night they came out. So the netting would cover you, and they wouldn’t crawl on you. Also, you had to shake out your boots every time you put them on.

AH: What kind of training did you do at gunnery school? What weapons did you familiarize yourself with?

SS: Well, in the classroom we had .50-caliber machine guns equipped to fire BBs. There must have been a million of these BBs all over the place when we got through. They would sweep them up, put them in buckets, and reuse them. These specially made machine guns were used to get us familiar with tracking an enemy plane. We also shot skeet as well. At first we would practice using a shotgun. Then they placed two of us in the back of a pickup truck. One was the loader and the other the shooter. They would drive real slowly, I’d say 15 miles per hour or so, and they had bulletproof houses that would release the skeet, and we would practice firing at it. They also had a huge oval track that had these vehicles on it that pulled targets around. Here we fired the .30-caliber machine guns.

AH: Any handgun training?

SS: Yes, we went to a dry riverbed, and it was the first time I ever fired a .45-caliber pistol. It was pretty high, and they put a guy on top to watch in case water would rush out of nowhere.

AH: Seems strange in such a dry climate.

SS: I know, but it did happen on occasion. Anyway, this was ideal for handgun training because it was the perfect backdrop. We were all lined up, and I was way down at the end so I couldn’t hear the sergeant who was instructing us what to do. There were quite a few men in this class. Well, all I heard was the word “Fire!” so I did. I popped off five rounds. He came running down screaming at me. I told him I couldn’t hear him. He saw the stripes on me so he stopped yelling and called to see the target. I had put all five rounds in a nice group on the target.

AH: Nice shooting.

SS: Well, there was a bit of luck there I’m sure. Not so with the buzzard.

AH: Buzzard?

SS: Yes. Every day this old buzzard would fly around. All you heard was dozens of machine guns trying to kill it.

AH: Ever hit the bird?

SS: Never. All those rounds, and the thing never got a scratch as far as I know. We finally completed our gunnery training and off we went to Avon Park, Florida, which is part of Sebring where the racetrack is located. They brought in a grayish-colored clay from North Carolina and made the runways and walkways.

AH: Why the clay?

SS: The entire field was built on a swamp. So the clay would withstand the climate better. They even built our barracks on top of it. They used a pile driver to drive these posts into the ground and erected the buildings on top of them. The water level was very high. In fact, they told us to be very careful, especially at night. Some of the water surrounding us was four or five feet deep. If you fell in, an alligator could get you.

AH: What a way to become a casualty. Did you do more training there?

SS: No, there they were assembling the crews for the B-17s. We all thought that we were headed to the South Pacific because we were in Florida. Everyone figured that they were trying to acclimate us to the tropical climate.

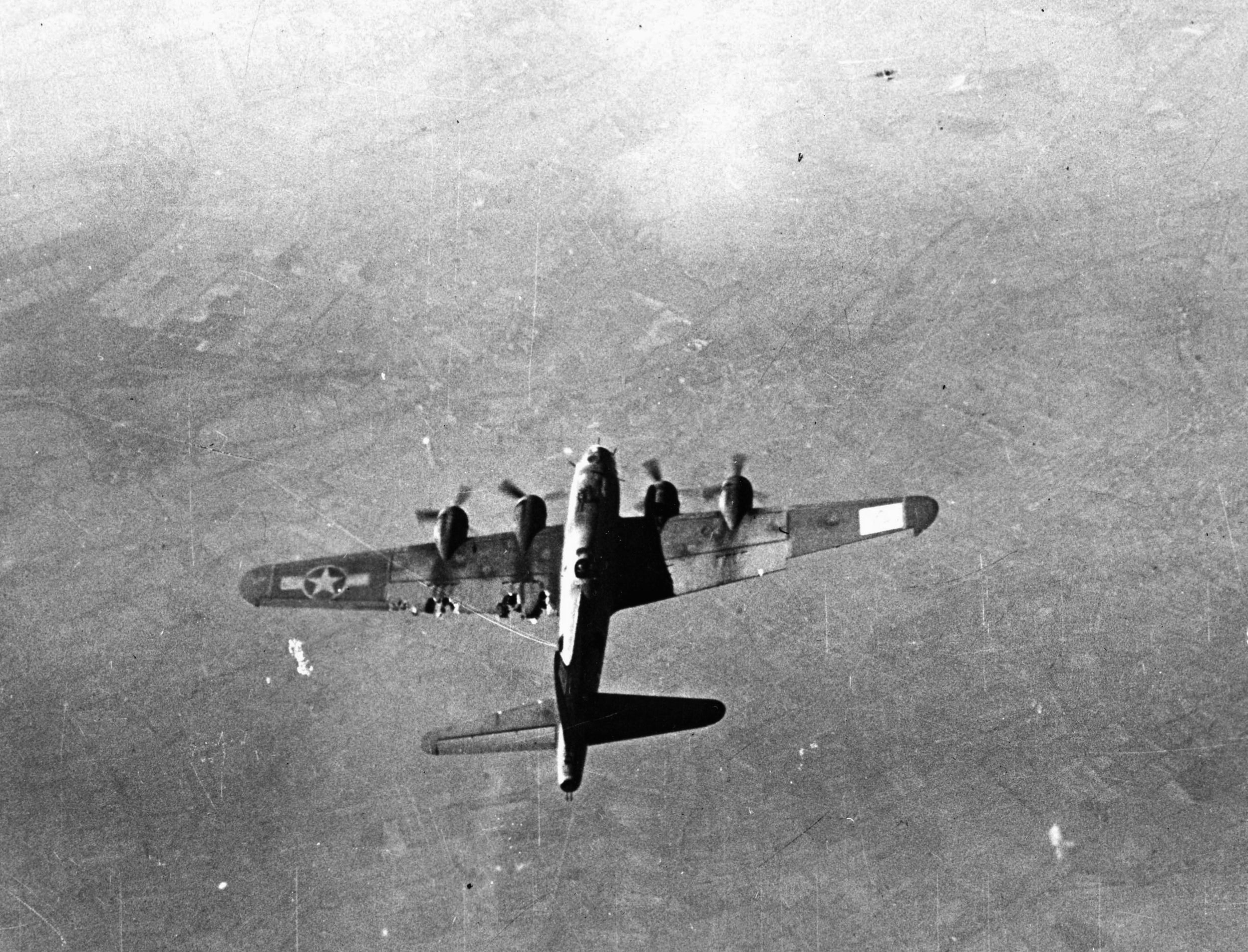

AH: Tell me about the B-17, also known as the Flying Fortress. Was it a good aircraft?

SS: It was a good bomber. Right after that they introduced the B-24 Liberator. It had a longer range and carried more bombs than the B-17. One bad thing about the B-24, in my opinion, is that all its controls were hydraulic. If hit, and you lost that hydraulic fluid, you were done. Also, the B-24 couldn’t glide if hit because it had parasol wings. They were flat on top and curved on the bottom. But even on the B-17 you could experience trouble.

AH: Like what?

SS: For example, if the landing gear didn’t go down, you had to hand crank it down before you could land. It took you 20 minutes to crank one wheel down. If I remember right, it was 300 or 400 turns to do it. But it was a good plane. I saw some of them come back with half of their tails shot off and they still made it.

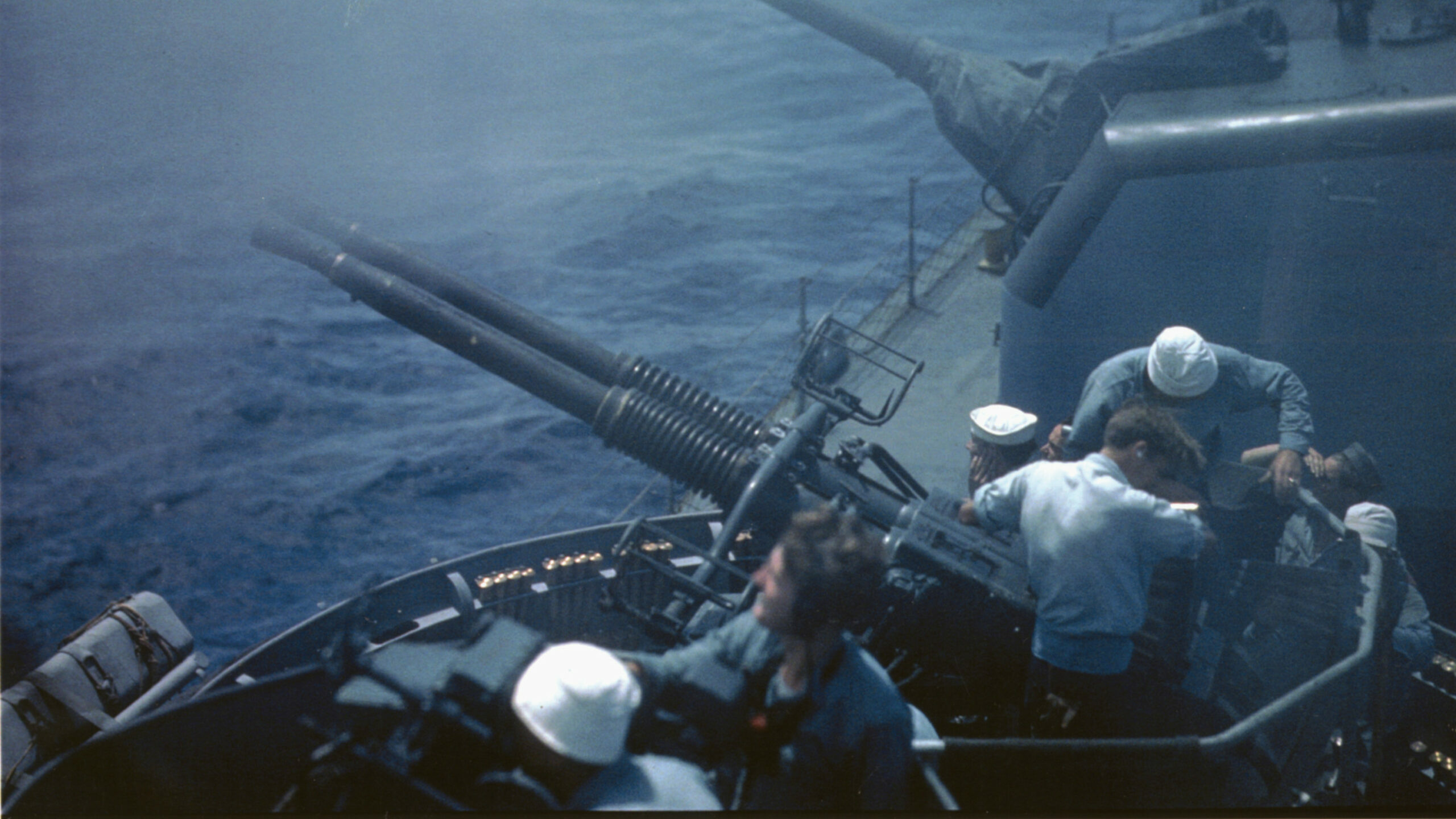

AH: The B-17 had quite a bit of firepower didn’t it?

SS: We flew in the G Model and we had a total of ten .50-caliber machine guns but we only carried 250 rounds for each gun. Most of the time we only got off four or five bursts, so we didn’t carry a lot to save on the weight.

AH: That makes sense.

SS: When we returned from a mission, the first thing they checked was our oxygen mask and our life vest, which we called a “Mae West.” Then they would ask if you fired your weapons. If we did they would clean them.

AH: What was the crew of a B-17?

SS: Pilot, copilot, navigator, bombardier, flight engineer, radio operator, ball turret gunner, tail gunner, and waist gunner.

AH: What was your job on the aircraft?

SS: I was the flight engineer. My duties included making sure all four engines were synchronized, the fuel mixture was correct, and we weren’t burning “too rich,” as we used to say. I also monitored the electrical wiring and controls, and watched the plane on takeoff for engine rpms, air intake, and other gauges and kept the pilot informed of that. If we got hit, I was also the top turret gunner.

AH: When was your plane shot down?

SS: On October 7, 1944. It was supposed to be a pretty safe mission.

AH: Where was it?

SS: It was somewhere over Germany. I can’t recall the name of the town. It seemed as if they were waiting for us. All of a sudden, German fighter planes were all over the place. I found out years later that we lost over 30 planes that day, and the Germans lost more than 50.

AH: Where was your aircraft hit?

SS: We caught some flak in our No. 4 engine, and it immediately caught fire. That is the outside engine on the copilot’s side. We were at an altitude of about 29,000 feet. The pilot told us, “Hang on boys, I’m taking her down.” He did a controlled dive to about 19,000 feet, and we put the fire out. The fire started in the engine’s lubricating oil tank. Each engine had its own tank. It held about 60 quarts of oil. But No. 4 didn’t have that after we put the fire out. This tank was right over the superchargers. These superchargers were exhaust driven, and they were the reason we could get a higher altitude. These manifolds became white hot because they took out the exhaust from the engines. They were so hot that the ground crew had to wait four hours to service the plane when we landed after a mission. I monitored the engine for about 40 minutes, but since we were flying with basically only three engines we were dropping altitude continuously. We also had lost our navigational equipment, so we were on what we called “dead reckoning.”

AH: Did the fire ignite again?

SS: I noticed that the smoke had changed color. It began to turn dark, which meant that the fuel was leaking into the oil on the manifold. I immediately called the pilot and informed him and suggested that he give the order to bail out.

AH: Did you ever have any parachute training?

SS: Never. This was the first time I would jump. And the crew never understood why I never wore my harness. I had on a 60-pound flak suit, so I figured I didn’t need it. However, that day when I got on board I put it on.

AH: Why?

SS: Don’t ask me why. I just did. I guess I had a premonition.

AH: Did everyone survive?

SS: Yes, we all did. I was counting the men as they jumped out, and I was one short. It was our radio operator. I went back to the radio compartment and told him to get out. Just as I did that the whole plane started to fill up with smoke. He jumped, and then I jumped right after him.

AH: You were the last one out. Where did you land?

SS: Yes I was. To this day, I’m not sure where it was. I want to say France or Belgium. After I opened my chute and was coming down I saw the plane crash in a field and burst into flames. I landed in a field where farmers were cutting wood. After I got out of my chute, I saw this guy coming at me with an axe. I spotted two German soldiers sitting in a staff car nearby as well. We were surrounded, so I went over to the soldiers and gave myself up. The civilians ran up and wanted to kill us. I heard that they hanged some crewmembers with their own parachutes. The soldiers motioned to them to get back to work.

AH: Why did the civilians hate you so much? If you were in Belgium or France, you were trying to help liberate their country.

SS: It wasn’t all civilians. I guess they felt that we were bombing their cities and countryside and they wanted revenge. Also, some civilians were pro-Nazi.

AH: What did they do with you?

SS: They took us to the Luftwaffe headquarters in town and made us sit on this big bench in the middle of the room. We were watched all the time. Even if you went to the bathroom the door was left open. One thing that I was surprised at is that they never took our cigarettes or matches from us.

AH: Yes, American cigarettes were sought after.

SS: I know, but they didn’t. There was a German officer sitting there playing chess with a civilian. Maybe it was a town official or mayor. I’m not sure. He asked us our plane number, squadron mission, etc. He spoke pretty good English, too. I stood up and told him, “Name, rank, and serial number is all you get according to the Geneva Convention!” He said, “Who are you?” I told him I was the senior NCO on the crew. He just laughed and said from now on we would take orders from Germans and like it.

AH: He had you there.

SS: He then said the war was over for us. He then asked if I got out of here what would I do. I said I had no idea. He then said that we were not airmen but gangsters from Chicago and we got $1,000 dollars for every mission we flew.

AH: Really?

SS: I yelled, “What? Now I know what I am going to do if I get out of here. I’m going to retire.” I was on my 17th mission when I got shot down. I was brazen I guess.

AH: I guess so.

SS: But they did show some respect for us. I think they considered airmen better than anyone else.

AH: Were you all together? Did they separate officers from enlisted?

SS: No. We all remained together. They captured us all in the same area. Our copilot was on a stretcher. He had been injured when he landed. They eventually took him away. Poor guy, it was his first mission, as I recall. The following morning the German guards formed a ring around us and marched us down the street. The civilians crowded around as we walked and they hollered, “American gangsters! American bastards! American SOBs.” They would have killed us if they got through. They took us to a building that looked as if it was situated on an airfield. They kept me separate and put me in a room by myself. The room was about 4 feet by 12 feet, with a wooden bed with a wooden block for a pillow. There was only one window, a pitcher, chamber pot, and tin cup. That was it. To signal the guard you pulled a latch and he would come to see what you wanted.

AH: Doesn’t seem very comfortable.

SS: Not at all. I could see a church with a beautiful steeple out the window. The bell would ring every 15 minutes. On the half hour the chime would sound different, and on the hour it was longer so you knew what time it was. At first it was nice. After about the second or third day it drove me crazy. So I decided to drive them crazy. I would ring for the guard and ask for water. I would take the water and put it in the chamber pot. I repeated this over and over, day or night. Time meant nothing to me.

AH: You were very defiant. What next?

SS: The ceiling was very high. They had a light that burned 24 hours in my room. At night they would cover my window so I couldn’t see out. After a few days they took me to the shower. I had no soap, a towel the size of a washcloth, but the water was hot. Then they gave me a double-edge razor. I had to dry shave. I thought I was going to rip my face off because I hadn’t shaved for a week or more. I also was still wearing the same clothes I had parachuted out of the plane with.

AH: Where to after that?

SS: They took me to this big room. It was beautiful with a huge desk that had to be over six feet long. A German officer was sitting there. He was immaculately dressed and spoke perfect English. He called me by my name and offered me a cigarette. He had this big Aladdin lamp he used as a cigarette lighter. When you hit one end, the flame would come out the other. I took a puff and inhaled and started coughing. I took the cigarette and put it out and tore it up so he couldn’t smoke it. He said, “I thought sergeants liked to smoke?” I said, “Yes, but I like cigarettes, not weeds!”

AH: You were cocky.

SS: Yes, I was young then. I looked on the walls and there were pictures of B-17s hanging everywhere. But what really amazed me is he had my traveling orders!

AH: From the States?

SS: Yes. He knew a lot about me.

AH: How?

SS: I think I know. I gave them to him.

AH: You! How?

SS: Let me explain. Before going overseas, I went home on leave. Everyone was having their picture taken. So I went to this very popular photography studio in town run by a Lithuanian. I had my uniform on, naturally, and had my travel orders in my jacket pocket. As I sat, he said, why not remove the orders because they stuck out of my pocket. So I did, and he put them on the counter. He took several pictures, went in the back room for about 10 minutes or so, came out, and took another one. I wasn’t paying attention. He must have taken my orders and made a copy. After I returned from overseas, I heard he had been arrested in a spy ring.

AH: That’s incredible.

SS: That’s the only way I can figure the Germans got my orders. They also snagged two or three doctors in that spy ring as well.

AH: This was in Scranton?

SS: No. Pittston, Pennsylvania. Everyone went to him because he did beautiful work. He must have gotten a lot of information that way. Anyway, this German officer had also done postgraduate work at the University of Pennsylvania. I didn’t believe him, but he showed me his school ring. Well, he could have gotten that off some G.I. We started talking about boxing, and he said (Max) Schmeling got robbed. I told him he got the beating he deserved.

AH: From Joe Louis?

SS: Yes.

AH: You should have been careful how you answered. He could have had you shot.

SS: Maybe deep inside I thought I wasn’t going to live. Who knows? But I wasn’t going to cower to them. He then told me about a boxer at the school who was good but not good enough to be champion. It then dawned on me—he wasn’t lying. He was there! He knew too much about the school and area to be making it up. He then told me that if the American soldiers were led by the German generals, we could rule the world. He felt that the Americans could adapt and think for themselves, and the German soldiers could not if their officers weren’t there. In his opinion, the German officers were far superior to the American officers. He said if they knew he was telling me this, he would be shot.

AH: Interesting point of view he had. When did you get to your next destination?

SS: The first part of November 1944, I arrived at Stalag Luft IV. It was located in Gross Tychow, Poland. We split up, but I ended up going to the camp with my friend, John Stacco, one of the gunners on my flight crew.

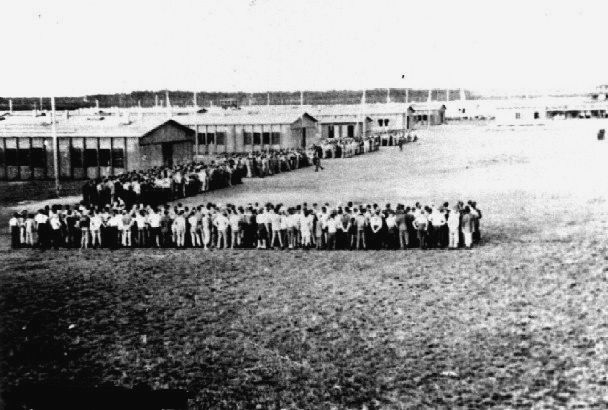

AH: What was the size of the camp?

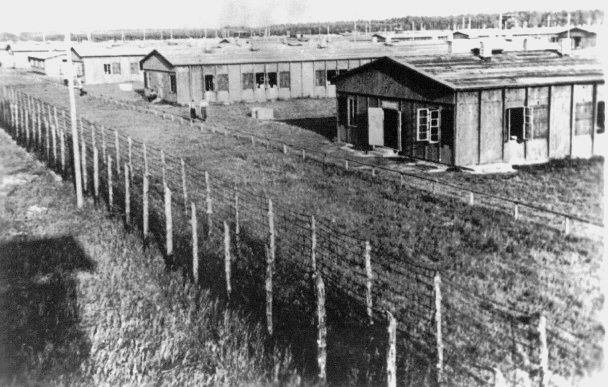

SS: The camp was divided into four lagers, or areas. Each lager had 10 barracks, one bathroom, and a building they called the mess hall. Between all the lagers we had approximately 10,000 prisoners there. So there were about 2,500 per lager and about 250 in each barracks. Actually only nine barracks were for us. The end one was a latrine and the washroom. Each barracks was divided into rooms with each room able to hold 10 to 12 men. In our room we had 27.

AH: That was crammed. A variety of nationalities, I assume?

SS: We had four Czechoslovakians, five Americans, several Canadians, and quite a few from Great Britain. We had triple-decker bunks, and the rest slept on the floor. Our mattresses were heavy bags filled with straw and one blanket. There was no pillow. We had the typical towers with the guards manning machine guns and two sets of barbed wire. The first stand of wire was the warning area. Sometimes a soccer ball would go into the wire, and they would get the guard’s attention to retrieve it. The guard would motion to go ahead. However, if you went there without his approval, he would shoot at you. The second set was supposedly electrified, but we never found out if that was true.

AH: Describe the day-to-day life at the camp.

SS: We would keep our area clean and had some chores around camp. They would let us play chess or soccer. Lights out was at 10 pm. Somehow we got a radio, which was strictly forbidden, and we listened to the BBC. They gave us one newspaper per barracks. Also, we had some South Africans who spoke German in our lager. They were Boers, the Dutch-Germans who settled there years ago.

AH: What about the food?

SS: Breakfast consisted of one cup of hot water—we had instant coffee from our Red Cross packages—and a slice of bread, half of which was flour and the other half was sawdust. All bread was dated. We received some bread that was five months old. We once got a cup of barley. We received a cup of soup at lunch and for supper a cup of potatoes. That was it. Sometimes we would get Red Cross packages, and we tried to save a few items from them. At Christmas the Red Cross brought in turkeys and hams. Only once we got that. It was propaganda to let them see how good they were treating us. Most of us lost quite a bit of weight on that meager diet. We were allowed to send a letter or card every so often as well. At least my family knew I was alive.

AH: So you remained in Stalag Luft IV for about three months until you started the march. Did they give you any advance warning?

SS: We were told a couple of days in advance. Anything we could carry, we did; otherwise it was left behind. I only had the clothes on my back and my blanket. I was wearing a British shirt, French pants, and a U.S. Army overcoat.

AH: Did they tell you why they were moving you?

SS: Yes, they said the Russians were closing in, and they didn’t want them to get ahold of us. So they put the ones that couldn’t walk on trains. The rest of us started to walk. We left in groups starting the first week of February. On the march it was me, John Stacco, a Canadian soldier with the last name of Stroub, and an Englishman named Sandy. We pooled our food together and we each had a blanket. At night we laid a blanket on the ground and covered ourselves with the other three as we huddled together for warmth. We never took our clothes off because of the cold, with the exception of our shoes. However, at one point I did not take my shoes off for 14 days straight.

AH: How did the guards treat you?

SS: Some treated us well and others looked down on us. We had one German who was a guard on the march who dropped his rifle and took off. Another one picked up his rifle and hollered for him to stop. This guy must have been a marksman because he killed him with one shot. Most of our guards were real young, older, or unfit for duty. This one old guy was a veteran of World War I and he was pretty decent. One day the Englishman, Sandy, who spoke fairly good German, asked him for medicine for diarrhea. Most of us had it. In fact, many of the guys suffered from dysentery. It was awful. Some guys bled it was so bad. Others were so weak from it they were left by the roadside. I suppose they died.

AH: Dysentery was a big killer in war.

SS: This old guard told us that we had the medicine right here. The ground was covered with ashes.

AH: Charcoal?

SS: Exactly. We picked up handfuls of it and ate it; even the ash off of burned wood.

AH: Did it help?

SS: Yes it did! It really helped us.

AH: Did the various groups of POWs take different roads?

SS: Yes. One day we passed a group of German soldiers retreating from the front. An American Piper Cub, which they used as a spotter plane, saw us walking. Well, the Germans weren’t stupid because they saw it too. That night they switched us and put us on the road the German soldiers had been traveling on. That night we found refuge in a farmer’s barn and huddled together on the straw. A flight of British Mosquitoes [DeHavilland fighter bombers] came over and hit us. There were three barns in a row. I was in the middle barn. The first wave of bombers struck the barn with the cattle in it, and the second wave strafed us. I was sleeping on the inside next to the wall. I was hit by shrapnel and received a head wound, and the Canadian was seriously wounded in the stomach. This was the end of April 1945.

AH: You were on the death march a long time. What happened to the Canadian?

SS: I was on the march for 75 days. We both got transported to a hospital. I saw him there and he had a huge hole in his stomach, but he was awake and in terrible pain. I knew he was dying, but they wouldn’t even give him morphine to kill the pain. So I went to see the doctor. He was a Frenchman who was also a prisoner and spoke very good English. I asked him to give my friend some morphine and make his last few hours on this earth bearable. He said, “Why waste morphine on him.” I grabbed him by the throat, and someone jumped between us. Good thing he did or I would have ripped his throat out. Well, he refused to work on me. I didn’t dare tell the German doctor. They might have had me shot.

AH: What about your wound?

SS: After eight or nine days, I got sick. I was paralyzed. I couldn’t even move.

AH: Probably poison from the shrapnel still in you.

SS: That’s what it was. One day this British corpsman came by and asked me what the problem was. I recall he had been taken prisoner at Dunkirk in 1940. He looked at my wound, and by now it had swelled up and was almost the size of a football. He got this ointment that looked like tar and applied it to my neck. In about 20 minutes it popped. And the stuff that came out of there! It was disgusting. But in a few hours, I felt much better.

AH: You were lucky indeed. The war had to be nearly over by this time.

SS: One day I got up and all the guards were gone and a Red Cross flag was flying on the flagpole. Someone had a radio and found the Armed Forces Network and guess what song was playing?

AH: What?

SS: Bing Crosby singing “Don’t Fence Me In.”

AH: How appropriate.

SS: Right after that a U.S. Army truck came to the gate. In fact, the truck went right through it.

AH: You were liberated?

SS: Yes, we were finally free. I was one of the lucky ones. I survived.

Frequent contributor Al Hemingway is a U.S. Marine Corps veteran of the Vietnam War.

Join The Conversation

Comments