By Eric Niderost

In 1611 Tokugawa Ieyasu had every reason to be pleased with himself. His son Hidetada was Shogun, supreme warlord of Japan, but in truth it was Ieyasu who ruled the country behind the scenes. Tokugawa Ieyasu was the last in a series of powerful figures who had finally ended decades of internecine strife still known as the sengoku-jidai, or “Age of the Country at War.”

Ieyasu had himself been Shogun from 1603 to 1605, then “retired,” ostensibly to enjoy the hard-earned fruits of his labors. Although in theory the Shogun was the servant of the Japanese emperor, in reality the emperor was little more than a revered figurehead. By officially handing over the reins of government to Hidetada, Ieyasu was serving notice that the House of Tokugawa was the real dynasty of Japan. Little did the old samurai know that his family would rule until 1868, making it one of the most successful in the history of the island nation.

Japan was a feudal society in 1611, with the country divided into fiefs ruled by lords called daimyo. These daimyo were part of a warrior caste called samurai, although not all samurai were feudal lords. Even lower status samurai were a breed apart, trained from early childhood in the arts of war. A generation before it had been possible for a peasant to become a samurai, but by 1611 such social mobility was a thing of the past. Peasants were forbidden to keep swords, much less practice military arts.

Ieyasu Ordered His Eldest Son to Commit Suicide…

Ieyasu was 68 years old in 1611. It was remarkable for anyone to reach such an advanced age in the 17th century, but for a samurai it was nothing short of miraculous. Warfare was hazardous enough, but the samurai code demanded ritual suicide (seppuku) in defeat or adversity. It was not unusual for an angry lord to demand a retainer’s suicide; once such an order was received, it had to be carried out immediately and without question. Ieyasu knew all too well what a samurai’s life demanded, especially if he was ambitious. In 1579 Ieyasu ordered his eldest son to commit suicide, in part because a more powerful warlord named Nobunaga wanted it.

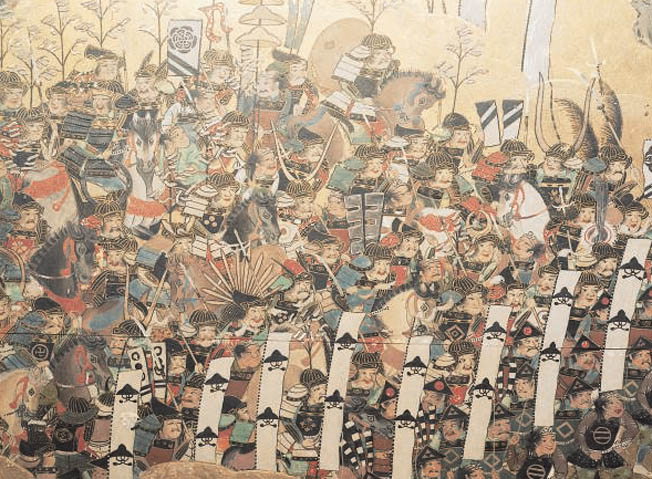

It was the Battle of Sekigahara, fought on October 21, 1600, that made Ieyasu master of Japan. Some have called it the greatest battle in Japanese history, a titanic struggle that involved as many as 160,000 men. Ieyasu utterly defeated his rivals, and many of the daimyo who attempted to flee the field were rounded up and executed. Even in the aftermath of the battle Ieyasu was able to view the freshly severed heads of his opponents, lined up in a gore-splattered row for his enjoyment.

Sekigahara was a turning point in Japanese history. In the flush of victory Ieyasu began a major feudal reorganization of the Home Islands. Supporters were rewarded, while those who failed to rally to the Tokugawa cause were punished. Since land was the basis of a daimyo’s wealth, Ieyasu reduced or expanded holdings on the basis of perceived loyalty to his house.

Wealth was based on the koku, the amount of rice needed to feed one man for a year. Even one koku implied a substantial amount. Tokugawa loyalist Maeda Toshinaga, for example, had his holding increased by 360,000 koku, which made him second only to Ieyasu himself in overall wealth. The daimyo who had their lands reduced were branded tozama, or “outer lords,” as a mark of Ieyasu’s displeasure. Yet the tozama were luckier than those who had everything taken away. Without land, a daimyo lost all power and prestige.

Each daimyo had his own private army of lower status samurai pledged to fight for him and guard his domains. When a lord was completely dispossessed, his samurai found themselves homeless and unemployed. Without employment they became ronin, masterless samurai, proud soldiers reduced to poverty-stricken vagabonds.

It seemed that everything was going Ieyasu’s way, but he still had to deal with the troublesome reality of Toyotomi Hideyori. In 1600 Hideyori was a child of seven, but he was heir to a powerful name. His father had been Toyotomi Hideyoshi, one of the other great figures of the Sengoku Jidai. A peasant by birth, Hideyoshi managed to achieve supreme power by 1590. Because of his humble origins Hideyoshi could not become Shogun, but he eventually became taiko, or “retired regent,” for the emperor.

Hideyoshi died in 1598, leaving behind five-year-old Hideyori as his son and heir. The taiko realized that without his strong hand to keep them in check the feudal lords might engage in a war of succession. Hideyori might be pushed aside, even killed, in the ensuing mad scramble for power.

A Master at Trickery and Deception

To prevent this Hideyoshi set up a Council of Regents to rule until young Hideyori came of age. The Regents pledged loyalty to the House of Toyotomi, sealing the pact with blood from their fingers. The story may be apocryphal, but it is said that when Ieyasu signed he engaged in some literal sleight of hand. He drew blood from behind his ear and not from his finger, which made the sanguinary signature null and void. Such trickery was typical of the man, and should have served as a warning to the Toyotomi faction.

As long as Hideyori was a child, Ieyasu felt he had little to fear. In the aftermath of the Battle of Sekigahara, Hideyori’s status was reduced from the future ruler of Japan to a mere daimyo. Yet Ieyasu was a seasoned campaigner in war and a master politician in peace. No fool, he recognized the threat that Hideyori represented. In 1603 Ieyasu’s granddaughter was given to Hideyori in marriage, the union lessening the tensions between the two rival houses.

The marriage might pour oil over troubled political waters, but Ieyasu knew the union was only a temporary expedient. Hideyori was immensely rich, enjoying the revenues of 657,000 koku. His feudal seat was at Osaka, one of the richest trading centers of the Japanese Home Islands. The young man might have lacked military experience, but he possessed Osaka Castle, the strongest fortress in all Japan.

The marriage might pour oil over troubled political waters, but Ieyasu knew the union was only a temporary expedient. Hideyori was immensely rich, enjoying the revenues of 657,000 koku. His feudal seat was at Osaka, one of the richest trading centers of the Japanese Home Islands. The young man might have lacked military experience, but he possessed Osaka Castle, the strongest fortress in all Japan.

Above all he had the Toyotomi name, a name that was still potent a decade after the taiko’s death. The magic of that name was a magnet that might attract all the disaffected elements of Japanese society. Worse still, Ieyasu was getting old, while Hideyori had not yet reached the prime of his young manhood. Ieyasu’s son Hidetada was competent but by no means brilliant. In fact, the latter’s poor-to-mediocre showing during the Sekigahara campaign left substantial doubts about his performance once Ieyasu died.

Ieyasu’s fears were somewhat assuaged by one of Hideyori’s guardians, Katsumoto Katagiri. Katagiri spread stories that Hideyori was growing up into an effeminate youth of little intelligence. These stories were a ruse, meant to lull Ieyasu into a false sense of security. The stratagem worked for several years, but finally unraveled in 1611.

In that year there was a personal meeting between Hideyori and Ieyasu that opened the old man’s eyes. Hideyori, then 18, was intelligent and far from effeminate. The two men met in Kyoto with all due pomp and ceremony; gifts and flattering courtesies were the order of the day. But beneath the glittering and cordial façade Ieyasu apparently resolved to eliminate this promising young man before the youth could supplant the House of Tokugawa. In that sense, then, the 1611 meeting was the beginning of Hideyori’s downfall.

The Fatal Naivety of Hideyori

For his part Hideyori seemed to harbor no animosity toward the older man. Certainly, there seems to be no evidence of political ambition either. Hideyori had married Ieyasu’s granddaughter, and thought of Ieyasu as a kind of adopted uncle. Intelligent though he was, Hideyori was naive—in the end, fatally naive—about “uncle” Ieyasu. Ieyasu’s past unscrupulous actions were a matter of public record, yet Hideyori chose to ignore the evidence.

Ieyasu now searched for a pretext to move against Hideyori. The young man and his mother, Yodogimi, Hideyoshi’s widow, had been building a temple in Osaka. By 1612 the Daibutsu Temple was complete. One of its most prominent features was a giant bronze statue of Buddha. This Great Buddha was the centerpiece of the shrine, a masterpiece of art and piety. It was also determined that a great bell would be cast for the complex.

It was said that Ieyasu had encouraged these building projects, secretly hoping they would bankrupt his young rival. Hideyori’s resources were abundant, and his coffers bottomless, so the attempt to ruin him financially came to nothing. Undaunted, Ieyasu tried a different tack. An inscription on Hideyori’s great bronze bell declared “In the east it greets the pale moon, and in the west bids farewell to the setting sun.” Ieyasu pretended to be offended by these innocuous lines, supposedly because they were insulting to the House of Tokugawa. Ieyasu, the lord of the east (Edo, now Tokyo, area), was linked with the “inferior” moon, while Hideyori, the lord of the west, was linked with the “superior” sun.

The charge was ridiculous, even by the touchy face-saving norms of samurai daimyo. Nevertheless, it was a beginning, the first political salvo in a campaign to weaken the House of Toyotomi. Ieyasu was worried about the strength of Osaka Castle. Through third parties he made it known that he might like to have Hideyori leave Osaka and go to another fief. Once the young man was separated from both his great revenues and his impregnable castle, the Toyotomi threat would be neutralized.

Osaka was Hideyori’s home. Rather than leave it, he told relatives he’d rather make it his tomb. It seems that Hideyori still hoped for an accommodation with his old “uncle,” and harbored no ambitions to rule Japan. He was still wise enough to know that, even if he were allowed to live as a petty lord, leaving Osaka would be damaging to his House.

Today’s tourist-oriented Osaka Castle, while impressive, is but a pale reflection of the mighty 1614 fortress. To begin with, the Osaka Castle of 1614 was a multilayered defense system of dry and wet moats, towers, stone walls, and galleries. The massive walls of the inner complex—still in existence today—rose 120 feet, and if the outer defenses are included the castle perimeter stretched nearly nine miles in circumference.

Osaka Castle was as Decadent as it was Impregnable

The heart of Osaka Castle was its honmaru or inner bailey, which featured a five-story tenshu (tower or keep) of probably eight internal stories. In most castles the main tenshu was the primary residence of the lord and his family. At Osaka the main tenshu was largely a storehouse; nearby another tower was a palatial home for Hideyori and mother Yodogimi. Osaka Castle wasn’t merely impregnable, it was also dazzlingly opulent. It was said the roofs were gilded, and the interiors were famous for their almost unprecedented luxury.

Geography also played a major role in Osaka Castle’s defense. The Temma, Yoda, and Yamato Rivers converged to the north, creating a labyrinth of muddy shoals, islands, and boggy rice paddies. The sea was much closer than it is today, and formed a buffer on the castle’s western flank. The Huano River and Nekoma Stream flowed to the east, and the Ikutama Canal hugged the outer defenses to the west.

At the 11th hour the ever-resourceful Katagiri suggested Hideyori’s mother Yodogimi go to Edo as a kind of peace assurance and honored “hostage.” The samurai confided that this suggestion was merely a ploy to gain time. Katagiri reasoned, and rightly so, that it might be years before Yodogimi actually had to leave, if ever. It would take time to find a suitable residence for such an honored “guest,” and if pressed Yodogimi could develop a diplomatic “illness.” Years might pass, and in the interim Ieyasu would probably die. Hide- yori would be in the prime of young manhood, ready to challenge the mediocre talents of Ieyasu’s son Hidetada.

It was a good plan, and well thought out, but in the end it was rejected. In fact, Yodogimi actually suspected Katagiri of treachery. He left Osaka under a cloud of suspicion and innuendo, never to return. With his departure, the House of Toyotomi lost a major supporter.

By June of 1614 it was clear to all that war was a virtual certainty between Ieyasu and Hideyori. It was clear to all, that is, except Hideyori, who still seemed to hope for peace and reconciliation. The young lord even sent back a large shipment of English gunpowder because he couldn’t sell it. Ieyasu took swift action, not only buying up the gunpowder but also purchasing five English artillery pieces. (At the time, European guns and powder were considered to be far superior to their Asian counterparts—an irony, given that gunpowder was invented in China.)

The five guns were typical of the period. Four of them were culverins, each weighing 4,000 pounds and firing a shot of about 18 pounds. The other gun was a sasher, which fired a five-pound shot. There is some controversy over Hideyori’s artillery. Some sources claim he was well stocked with ordnance, while others aver he largely had inferior-quality Chinese guns.

Many Ronin Responded to Hideyori’s Call

It took time, but Hideyori finally awakened to the Tokugawa threat. Ieyasu’s “grandfatherly” concern and affable demeanor had lulled the young man into a false sense of security. Now alerted, Hideyori issued an appeal for all loyal daimyo to rally to the House of Toyotomi. Not one of the great lords responded, mute but eloquent testimony to the 14 years of Ieyasu’s rule. Even those who might have been inclined to answer the summons had second thoughts when the “terrible old man” held their families hostage.

The ronin, or masterless samurai, responded to Hideyori’s call in unprecedented numbers, eager at a chance for both military employment and revenge. Ronin literally means “wave men,” restless like the surging ocean tides. They were well named, because ronin were a sea of humanity whose numbers and determination for revenge might tip the scales against Ieyasu.

Eventually Hideyori had a huge army of some 90,000 largely veteran fighters. The daimyo who did support Hideyori were, like the ronin, those who were nursing a grievance against Ieyasu. Chosokabe Shigenari, for example, was the ex-lord of Tosa, who had been stripped of all rank and power and forced to live in obscurity.

Some of the Hideyori daimyo were Christians like Goto Motosugu and Kimura Shienari. There had been intermittent persecutions of Japanese Christians during this period, including some martyrdoms of converts and missionary priests. A Jesuit recalled that in Hide-yori’s army “there were so many crosses, Jesu’s and Sant Iagos (Saint James) on their flags, tents, and other martial insignia [it must] have made Ieyasu sick to his stomach.” These Christian samurai were eager to fight a man whom they considered a devil of war in the name of the Prince of Peace.

Hideyori’s army, sometimes called the Osaka or Western forces, lacked a paramount military leader. The young daimyo had been raised in all the martial disciplines expected of a samurai, but he lacked practical military experience. His name and his father’s Golden Gourd uma-jiroshi (standard) might raise an army, but it was quite another proposition to lead it. Most of the daimyo who did respond to the call were men of competence but not brilliance.

While there wasn’t any supreme warlord to command the Osaka garrison forces, Sanada Yukimura played an important role in siege preparations. A celebrated master of defense, he had held up Ieyasu’s son Hidetada at Ueda Castle in 1600. With Sanada’s defensive expertise, Osaka Castle was truly going to be a tough nut to crack. Sanada was something of a swashbuckler; to join Hideyori he had escaped from a monastery by stealing a horse. He had been forced to shave his head and don monk’s robes in a kind of forced exile, but now he was back with a vengeance.

Sanada soon made his presence felt. To the west of Osaka Castle was the Ikutama Canal, and to the east a stream called Nekoma. Thousands of ronin replaced swords with spades and set to work building a moat that linked the canal and stream. The resulting excavation was an impressive 240 feet wide and 36 feet deep, and when the waters flowed in they rose to a depth of 12 to 24 feet.

Sanada’s Brilliant Plan

Not content with this new moat, Sanada built a barbican in front of it and the Hanchone Gate. Called the Sanada Maru or Sanada Barbican after its creator, the outwork consisted of an earthworks and stockade behind a dry moat and palisade.

Although his fame rested on his successful castle defense of 1600, Sanada firmly believed that the best defense is offense. In the fall of 1614 Hideyori presided over a grand council of war to discuss the situation. In the end a purely defensive plan was adopted, a line of thinking encouraged by Osaka Castle’s apparent invincibility. Sanada disagreed; he favored a march on Kyoto to seize the emperor. His Majesty was a powerful symbol, a talisman of national identity. If he was on Hideyori’s side the Toyotomi cause would gain added luster. Ieyasu might even be declared a rebel and traitor, a political pariah few would want to follow. It was a brilliant plan, but Osaka Castle’s massive fortifications seem to have cast a spell on young Hideyori. He opted for a purely passive strategy of waiting for Ieyasu’s inevitable attack.

That November Ieyasu marshaled his troops for an attack on Osaka. The old man’s son, Shogun Hidetada, was his willing accomplice. Between them they raised 194,000 troops, roughly double that of the Osaka forces. The coming operation would be known as the Winter Campaign, a contest that would ultimately chart the course of Japanese history.

Ieyasu’s first task was to drive in the various Osaka outposts that guarded the approaches to the main castle. An Osaka fort at the mouth of the Kizu River guarded the supply routes into the castle, though provisions on hand were enough to last several years. Of course Ieyasu didn’t know how well stocked Osaka was, so cutting off the castle’s supply route made perfect sense.

The fort was garrisoned by 800 men under a Christian daimyo named Akashi Morishige. A force of 3,000 Eastern troops was dispatched under Hachisuka Yoshishige to take the outpost by land and water. Yoshishige crowded his samurai into 40 boats for a perilous river crossing, while some of his men simultaneously attacked from the fort’s landward side. The Easterners faced rough opposition from some Osaka guard boats, placed there to block a water crossing. Musket fire peppered the advancing vessels, a steady stream of bullets that splintered wooden sides and drilled through samurai armor and flesh.

Casualties were heavy, but bloodied boats pressed forward and finally reached the opposite shore. In the meantime, the landward attack diverted the attention of at least some of the defenders. Assaulted on two sides, the garrison was finally overwhelmed and put to the sword. The fort was razed, and Eastern troops were stationed in the area to prevent any supplies from reaching the beleaguered castle.

The capture of the Kizu Fort set the pattern for the next weeks. One by one the outposts were reduced, but the main Osaka Castle works were as yet untested. To try both the strength of Osaka Castle and the mettle of its defenders, Ieyasu ordered a major attack on the castle’s southern flank. The old warrior was well aware of Osaka Castle’s formidable reputation, but probably dreaded a lengthy siege. Sieges can be drawn-out affairs, and Ieyasu knew that time was on Hideyori’s side. The longer he held out, the weaker Ieyasu would seem in the eyes of daimyo awaiting the chance to throw off his yoke.

It was the political survival of his family that was uppermost in the old man’s mind. An all-out attack on such formidable defenses was a risky maneuver, but Ieyasu had taken risks his entire life. He cared little if a victory was dearly bought, as long as he achieved his ends. Unfortunately Ieyasu couldn’t have picked a worse place to launch a major assault. The castle’s southern defenses were held by the redoubtable Sanada, a man who was probably Hideyori’s best overall commander.

Sanada Naps Peacefully Before the Battle to Come…

The southern attack was given to Maeda Toshitsune, an Eastern general who was able but not in Sanada’s league. Sanada had been forewarned of the Eastern attack by alert scouts. Knowing the Eastern army would try to seize his outpost at Sasayama, Sanada purposely evacuated its garrison. When the Eastern troops took the deserted fort they were elated by the bloodless victory, scrambling about the battlements with mighty shouts.

The main southern assault was to begin before dawn on the fourth of the 12th moon—January 3, 1615 by the Western solar calendar. Sanada’s officers stood by in amazement as he leaned against a post, apparently sleeping. This nonchalance in the face of the enemy was genuine, but it also was a way of putting heart into his men. After all, Ieyasu’s troops couldn’t be much of a threat if Sanada could take a nap before battle.

The sun finally rose over Osaka, its beams gilding 10,000 Eastern soldiers poised for the assault. Each samurai had a hashimono or flag attached to his back by means of a pole. As the soldiers advanced their billowing flags shook with each footfall, the undulations moving like a multihued cloth sea. It was a hypnotic effect, made even more dazzling by the presence of Ii Naotaka’s “Red Devils.” These troops wore red lacquered armor, their units cutting a crimson swath through the Eastern army’s tight formations.

Sanada was unimpressed by all this color and panoply. He wanted to goad his enemies into a rash attack, so he had a soldier shout insults from the palisade. “How was hunting at Sasayama?” the soldier asked, then added ironically that “the game [the garrison] had been scared away.” “If you have any leisure,” the soldier taunted, “come and fall upon us: we have a few country-made arrows for you.”

The “Red Devils” Succeeded in Scaling the Castle Walls

Stung by the Osaka insults, Maeda’s troops rushed forward to scale the wall, only to be met with a withering fire from Sanada’s musketmen. Muskets flamed in gray-white gouts of smoke, each discharge spitting lead that felled scores of climbing samurai. Decimated survivors fell back to regroup their shattered formations while fresh units took their place. None of Maeda’s divisions could make any headway.

A bit farther down the castle’s southern defenses the “Red Devils” actually succeeded in scaling the walls and descended into the outer bailey like a crimson flood. Osaka commander Kimura Shiemaru was ready to seal the break with 8,000 troops, many of them armed with muskets. Once again muskets pumped a steady rain of lead into closely packed ranks, felling hundreds within minutes. Soon the outer bailey was choked with scarlet corpses, their blood dyeing their armor a deeper shade of red.

Ieyasu had his answer; Osaka Castle was indeed impregnable. Shogun Hidetada was all for renewing the assault, but was sternly overruled by his father. Instead Ieyasu ordered that a stockade and rampart be built around the fortress, the action signaling a formal siege. It was January, in the depth of a bitter Japanese winter, and the besieging troops found themselves literally out in the cold.

The black snouts of some 300 Ieyasu guns ringed the castle. The larger artillery pieces didn’t have wheeled gun carriages, but were supported by rice bags stuffed with straw. Samurai and ashigaru (common soldiers) shivered in the cold, their breath misting into vapor in the frigid air. Officers found a degree of warmth in quilted cotton haori (surcoats), but whatever the rank, all were united in cold-numbed misery.

Since Osaka Castle’s defenses proved too strong, Ieyasu was prepared to use less conventional methods. Completely unscrupulous, a past master of political deception and intrigue, the old man decided to use bribery to gain entrance to the castle. But unfortunately Ieyasu’s usually keen instincts seem to have deserted him, or at least become diluted with age.

The man he attempted to bribe was Sanada, whose contempt for the Tokugawas was equaled by his personal integrity. Sanada briskly rejected the offer, and publicly published the bribery attempt so all could witness the old man’s shame. Ieyasu tried again, this time bribing a subordinate Osaka commander named Nanjo Tadashige. Nanjo readily agreed to open the gates for a price—but was found out before his treachery could be accomplished. The traitor was beheaded, and Ieyasu still stood outside Osaka Castle’s formidable gates.

Ieyasu now went for bigger game. He knew that Hideyori’s mother Yodogimi had influence over her son, and that she was not as courageous as some of her public statements would suggest. She, not Hideyori, might be the flaw in the defense, the weakest link in the chain. On January 15, 1615 Ieyasu had his best gunners train their culverins on the palace tower where Yodogimi kept her private apartments. The palace was distinct from the main tenshu or keep.

Politics and Ploys of Battle

After a few trial shots, the gunners found the range. A 13-pound ball crashed through the palace walls and smashed into a tea cabinet, in the process killing two of Yodogimi’s ladies. Another shot crashed into the family shrine room, narrowly missing Hideyori himself. Even near misses rattled nerves with their ear-splitting din, and by most accounts—though this is disputed—Osaka Castle could not respond in kind. The castle had many Ming Chinese bronze cannon of inferior quality to European designs, and this artillery was further handicapped by short ranges.

The physical bombardment was accompanied by a diplomatic salvo. Peace negotiations were opened, a barrage of honeyed words and alluring promises designed to sap the strength and weaken the resolve of the defenders. Predictably Yodogimi added her voice to the counsels of peace, and she was joined in this by several of Hideyori’s daimyo. It’s hard to determine motivations after 400 years, but probably Hideyori’s subordinates hoped to curry favor with Ieyasu. If they were instrumental in making peace, the old man might reward them by restoring all or part of their former domains.

Sanada vehemently disagreed with the peace faction, arguing that Ieyasu was untrustworthy. The “terrible old man” was famous for twisting agreements to suit his own ends. Years before, Ieyasu had entered into an agreement with some monks, swearing their temples would be restored “to their original state.” Once the pact was signed, Ieyasu torched the temples and burned them to the ground. This was no breach of faith, Ieyasu declared with a straight face, because the temple site had been restored to its original state—empty fields!

Hideyori should have held out. His troops were brave, loyal, and fanatically anti-Tokugawa. The defenses might be battered in spots, but they were still basically impregnable. Water was plentiful, and there was enough rice and other stocks of food to last several years. Ieyasu’s allies might grow restive, or even defect, if the siege lasted two or three years.

Unfortunately for the Toyotomi cause, Hideyori allowed himself to be swayed by the peace faction. It was said that his mother Yodogimi was particularly frightened when Ieyasu had his entire army shout battle cries—almost 200,000 voices combined to produce a swelling roar. A “peace” was concluded by which Ieyasu withdrew his army from Osaka and lifted the siege. There would be a general amnesty and Hideyori would continue to rule in Osaka. Ieyasu sealed the pact with blood from his own fingertip, as was the custom.

The bulk of the Eastern army did withdraw, but other units remained ominously in place. Without any prior consultation with Hideyori the remaining Eastern commander began filling in Osaka Castle’s outer moat. During the course of the negotiations the moats were mentioned in passing, but there was nothing in the final treaty that said anything about filling them in. Soon the entire outer moat was filled with soil, and then Ieyasu’s men began filling in the second moat as well.

Hideyori and his subordinates were aghast and protested the action, but were put off by excuses and apologies. After 26 days the second moat was also a thing of the past. Now Osaka Castle’s defenses were seriously compromised, as Ieyasu had intended from the start. Deceit had accomplished what military action could not.

The Fate of Osaka Castle

Finally, the moat-filling controversy reached the ears of Ieyasu himself. Disingenuous as always, Ieyasu claimed the moat filling had no official sanction from him. He was somewhat puzzled by the protest, however. After all, he reasoned, peace had been restored. There was no need for defensive moats!

Peace lasted only a few months. Ieyasu intended to crush the House of Toyotomi “finally, effectively, drastically.” Ironically when Hideyori attempted to excavate the filled moats again, Ieyasu used the action as a pretext for war. Wasn’t digging moats a “hostile” act?

In a sense the summer campaign of 1615 was a postscript to the previous fighting. Hide- yori’s troops had lost none of their skills, but they were mishandled in open battle. Due in part to a series of unfortunate tactical mistakes, Hideyori’s army was defeated and forced to fall back on Osaka Castle.

The fortress was not the mighty work it had been six months earlier, and it soon fell. The tower that sheltered Hideyori and his mother was soon engulfed in flames. Hideyori committed suicide, and Yodogimi either followed suit or was dispatched

With the Winter Siege of Osaka Castle, old samurai Tokugawa Ieyasu hoped to crush the House of Toyotomi and change the course of Japanese history.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments