By Peter Kros

Ian Fleming’s biography would certainly include creating the famous British spy James Bond, but the author also led a secret life of his own. From first to last during World War II he gathered intelligence and hatched secret plots to bring down the Nazis.

Ian Fleming’s Early Years

Fleming was born on May 28, 1908 in London of a wealthy banking family. His father Valentine Fleming was a Scottish moneyman who had inherited a fortune from his own father Robert, the chairman of a firm that bore his name. Ian’s mother was the stunning Evelyn St. Croix Rose, noted for her forthright and vociferous stands on many issues.

Ian had three brothers—Peter, Richard, and Michael. Peter and Ian were sent to a boarding school called Dumford in 1915, one year after their father was appointed a major in the British Army where he saw action in France during World War I. At Dumford, Ian began his lifelong interest in reading, especially action novels and stories of far-off places. Ian’s young life was violently shaken when, on May 20, 1917, Valentine Fleming was killed in action in France (Winston Churchill wrote a tribute). Ian was only a week short of his ninth birthday when his father died, and he felt the loss badly. He now looked to his brother Peter as his new father figure.

At the beginning of the school year of 1921, both Peter and Ian were enrolled at Eaton, where Ian was unhappy. He did, however, excel at track and won two awards. A change came in 1926 when he was transferred to the Royal Military College at Sandhurst. Like Eaton, Sandhurst did not measure up to Ian’s interests and he left, now bound for a small school in Kitzbühel, Austria. He found the crisp alpine air much more agreeable, and his education and personal life began to flourish. He devoted more time to writing, and after graduation applied for a position with Reuters news service. Using family connections, he was hired as an assistant to the editor, Bernard Rickatson-Halt. He was such a good writer that he was promoted to run down stories outside of the pressroom. In time, he left Reuters for other endeavors.

From Reporter to British Spy

Shortly before Britain entered World War II, Ian Fleming was working as a reporter for the London Times. He was regarded as a superb writer and a man who had more than his share of contacts. He traveled to the old Soviet Union, where he covered the Metro-Vickers trial in which three British citizens were charged by the Russian secret police on trumped-up charges. His reports on the trial gave him a wide following and his name became known in the right places.

After a stint as a London stockbroker, a job he disliked, he was plucked from obscurity into the dazzling work of naval intelligence as the personal assistant to Admiral John Godfrey, then head of British Naval Intelligence. Working out of Room 39, also known as NID (Naval Intelligence Division), Ian Fleming sat at the helm of all British naval intelligence and was privy to all the secrets of the far-flung British naval empire. Fleming began this military career part-time with the rank of lieutenant but soon commander, with three stripes on his sleeve. (In his fictionalized books, 007 was also a commander.) Admiral Godfrey wrote complimentary reports on his new aide, stating at one point, “Ian carr[ied] out the multifarious duties of personal assistant, a job which has no defined frontiers, with outstanding success.”

Fleming soon joined the NID full time and was assigned to work in Section 17, which handled a steady stream of secret information coming in from the OIC (Operational Intelligence Center) and other departments of NID. Writing after the war of his time at NID, Fleming said that he was “a convenient channel for confidential matters connected with subversive organizations, and for undertaking confidential missions abroad, either alone or with NID.” Fleming’s code number was “I 7F.”

Godfrey gave him new duties. Ian was to liaise on NID’s behalf with the Secret Intelligence Service (SIS), the Political Warfare Executive, and the JIC (Joint Intelligence Committee). As part of his duties, Fleming was also responsible for hiring members of the Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve.

As the war began, NID watched the progress of German warships, especially in the North Sea and North Atlantic, the major shipping lanes surrounding the British Isles. One of Fleming’s teachers in Room 39 was an Australian pilot, Sydney Cotton, who flew a dangerous mission over the North German ports and photographed a large portion of the German fleet at anchor. Cotton was able to tinker with his plane and succeeded in mounting his aerial cameras on the wings to ensure that they’d work. Fleming and Cotton met often and discussed how to use new and untested gadgets for intelligence gathering.

An Organization for “Dirty Tricks”

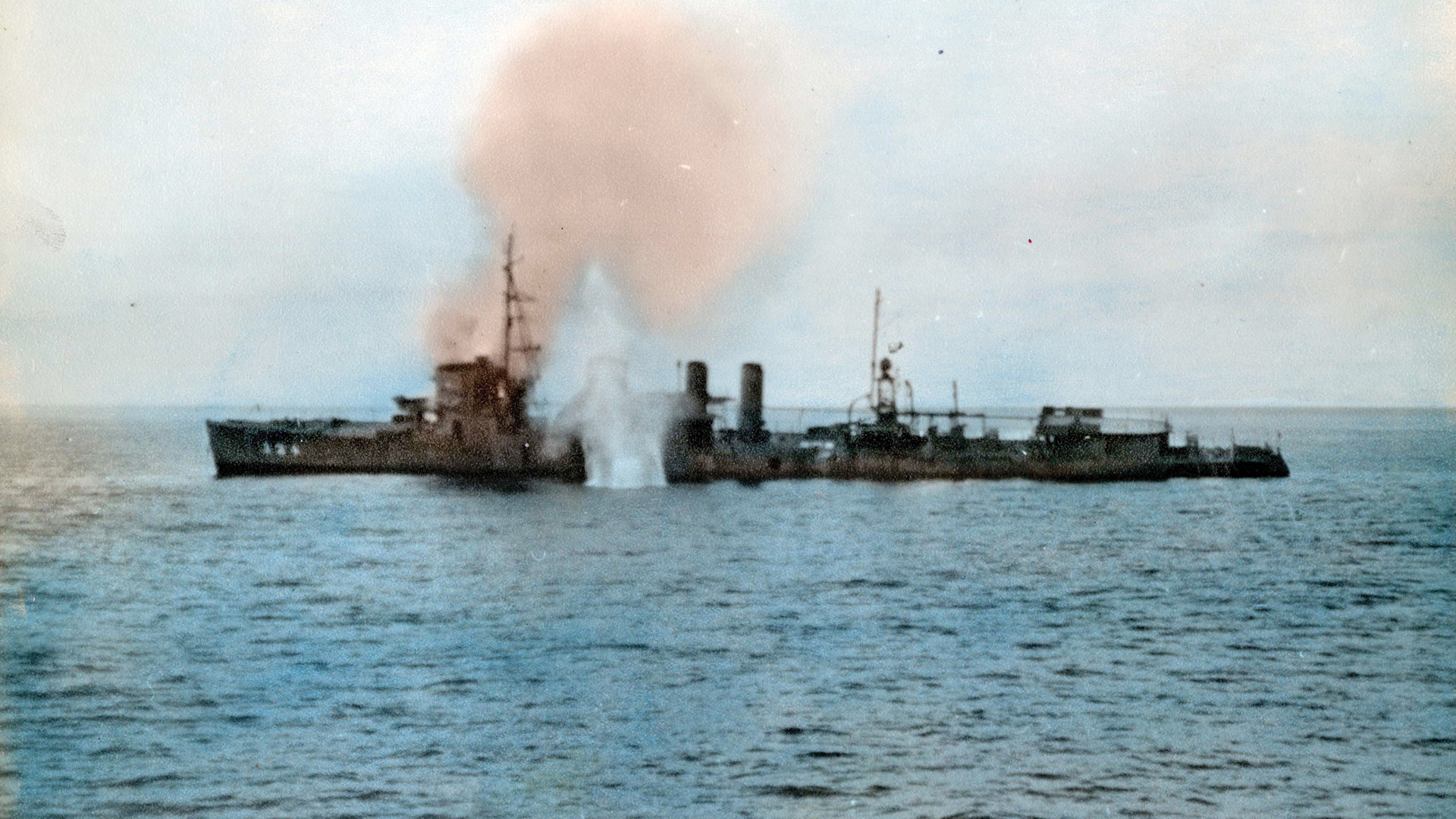

NID took special interest in a plan to prevent the River Danube from falling into the hands of the German Navy. The Danube was a vital shipping link by which Germans could gain access to the critical Romanian oil fields. Fleming was assigned as the liaison to MI (R), a kind of “dirty tricks” organization that ran subversive operations on behalf of British Intelligence. One successful outgrowth of this plan was the leasing of a number of barges on the Danube by a British shipping company, making them unavailable to the Third Reich. A second NID operation was the scuttling of concrete-loaded barges at strategic parts of the river between the ports in Yugoslavia and Romania. In this effort, Fleming worked with Merlin Minshall, the British vice-consul in Bucharest, to oversee operational strategies.

Minshall took part in the Danube operation, following the barges in his own, high-powered craft, which was to be used to rescue the barges’ crewmen. En route, Minshall’s boat ran out of fuel. In a scene that would have made 007 proud, Minshall narrowly escaped into another craft, with the Nazis in hot pursuit. The Danube operation was a flop, but not for lack of trying.

As Fleming broadened his circles in naval intelligence, he came upon a number of adventurous men who lived for danger. Many became colleagues. In his book, Ian Fleming—The Man Behind James Bond, author Andrew Lycett points to three acquaintances as models for the Bond role: Michael Mason, Wilfred Dunderdale and Alexander Glen. Mason was a boxer and a trapper in the wilds of Canada. Commander Dunderdale worked for the super-secret SIS (Secret Intelligence Service) and was instrumental in purloining the plans of the Polish Enigma coding device, then in use by the German armed forces. Glen was the assistant naval attaché in Belgrade.

The Origin of 007

Incidentally, Fleming’s knowledge of vital military secrets led him to Bond’s designation of 007. While doing historical research, Fleming came across details of the British success in breaking a German code during World War I, leading to the Zimmerman Telegram incident. British codebreakers deciphered diplomatic messages sent by German Foreign Minister Arthur Zimmerman to the German minister in Mexico giving details of the new policy of unrestricted submarine warfare against the United States. Zimmerman further stated that if Mexico made trouble for the United States and Germany won the war, Germany would work to return New Mexico, Arizona, and parts of Texas to Mexico. The number given by the Germans to these diplomatic exchanges was 0070.

Before and during the early months of the war, much good intelligence was coming out of France. But the source was eliminated with the German victory of May-June 1940. Admiral Godfrey sent Fleming to France on June 13, 1940 to assess the situation.

Fleming spent two weeks there, serving as the liaison officer between British Intelligence and Vichy French Admiral Jean Darlan. Because bad blood existed between Darlan and the new British naval attaché Captain Cedric Holland, Fleming tried to get into the admiral’s good graces, purely for NID’s benefit. With German forces bearing down their collective necks, Fleming and other members of the British mission began burning all their important papers. After he departed France, Ian was sent under cover to Tangier to monitor British Naval Intelligence operations near the vital Suez Canal.

By the spring of 1941, the United States and Great Britain agreed to share intelligence. Only a handful of men in the Roosevelt administration—and not even Congress—knew about the arrangement. In order to work out the parameters of this intelligence bonanza, Winston Churchill sent Admiral Godfrey and Ian Fleming to Washington in May 1941. They arrived in New York via the Pan Am Clipper, staying in the posh St. Regis Hotel. Soon they were in contact with William Stephenson, codenamed “Intrepid,” who was in charge of the secret British spy organization in the United States, BSC (British Security Coordination). After successful meetings with Stephenson, Fleming and Godfrey traveled to Washington for high-level discussions with American officials.

Through the intervention of William Wiseman, Britain’s World War I spymaster in the United States, Godfrey had a private meeting with President Roosevelt to discuss the USA-UK intelligence arrangements. The meeting was pivotal. Within three weeks of Godfrey’s departure, FDR appointed William Donovan head of the COI, Coordinator of Information, America’s first spy network. (The COI would later become the OSS.)

Their next stop was a highly charged audience with Director J. Edgar Hoover at the FBI. Hoover took an immediate dislike to his two visitors, sensing they were interfering on his turf. Hoover took Godfrey and Fleming on a tour of the FBI shooting range and forensic laboratory. When it was over, the gruff G-man quickly showed them the door.

Fleming was Known for his Unconventional Methods

Godfrey and Fleming spent the remainder of their stay in Washington holding talks with Donovan. Both men worked day and night to help the American lay the groundwork for the OSS, with Fleming often shuttling between Donovan’s home and their temporary offices. Fleming is believed to have written two important memoranda for Donovan on how to create America’s new intelligence agency.

Back in Britain, Fleming’s modus operandi was unconventional at best, as illustrated by his use of captured German naval officers. He arranged for a few seized German naval officers to accompany him to a posh London restaurant where he fed them the best meal and supplied the finest wine. In return, he was able to glean important naval matters from a U-boat commander who was too drunk to mind.

Later in 1941, Fleming went on his most intricate mission yet. Bill Donovan was making a tour of the Mediterranean, checking on the status of Britain’s plans to resist Hitler. Among his several stops were Madrid and Lisbon. Fleming went to Gibraltar to meet with Donovan. There he told the American about an NID operation he was running, Operation Golden Eye. It was meant to carry out sabotage and open communications links in case Germany invaded Spain. Fortunately, the plan was never needed.

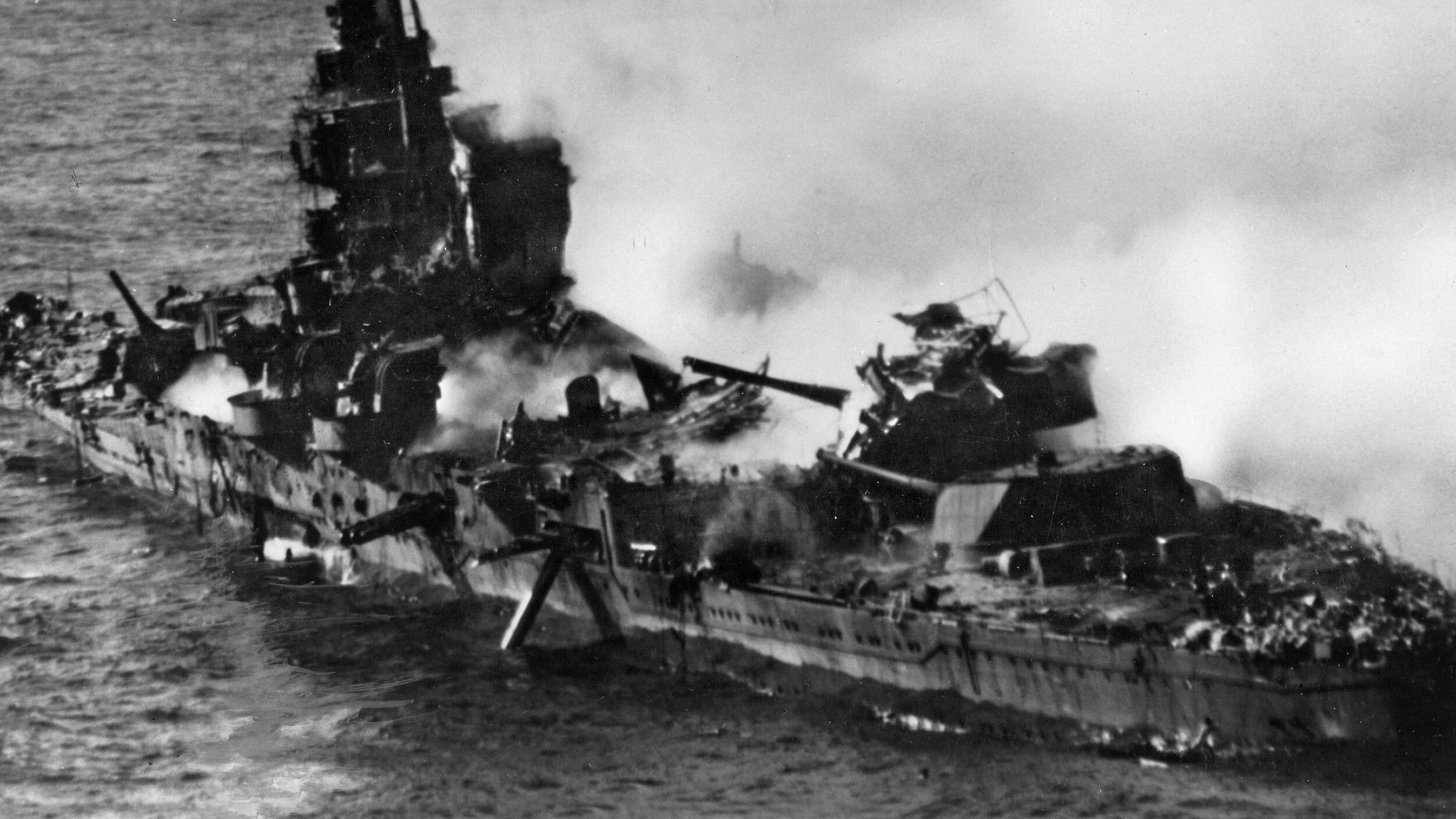

Fleming was also involved in one of the most successful deception operations of the war. Working out of the Room 39 headquarters, Fleming and British intelligence devised a plan to fool the Germans into believing the 1943 invasion of Europe would take place in the Balkans instead of Sicily. To that effect, Fleming had three of his most trusted agents—Vladimir Wilson, the one-time naval attaché in Istanbul; Robert Harling of NID; and Alexander Glen—make a fake observation of the landing beaches along the coasts of Albania, Greece, and parts of Yugoslavia, under the watchful eyes of the Germans. It was all part of the larger deception plan that became known as “The Man Who Never Was” project. The most notorious part was the placing of the body of a drowned British naval officer into the sea along the Spanish coast—as if he were the victim of a plane crash—carrying fake documents purporting an Allied invasion of the eastern Mediterranean. The Germans fell for this ruse completely.

Fleming also trained at the Special Operations Executive (SOE) secret base in Canada, called Camp X. It was here that men bound for undercover operations in Europe were prepared in all aspects of guerrilla warfare. Located on the north shore of Lake Ontario and hidden from view, Camp X was run by William Stephenson’s BSC in New York, with the cooperation of the British Secret Intelligence Service (SIS). Here agents learned about forged papers, demolition, hand-to-hand combat, secret inks, and the art of silent killing.

Back in England, Fleming took on new work supporting the coming D-day invasion of northern Europe. He assembled a large military library to aid in assault preparations. Working in cooperation with the Inter-Services Topographical Division at Oxford University, Fleming was able to accumulate a superb collection of maps and reports on the countries in which the Allied troops would be fighting.

Fleming’s “Red Indians”

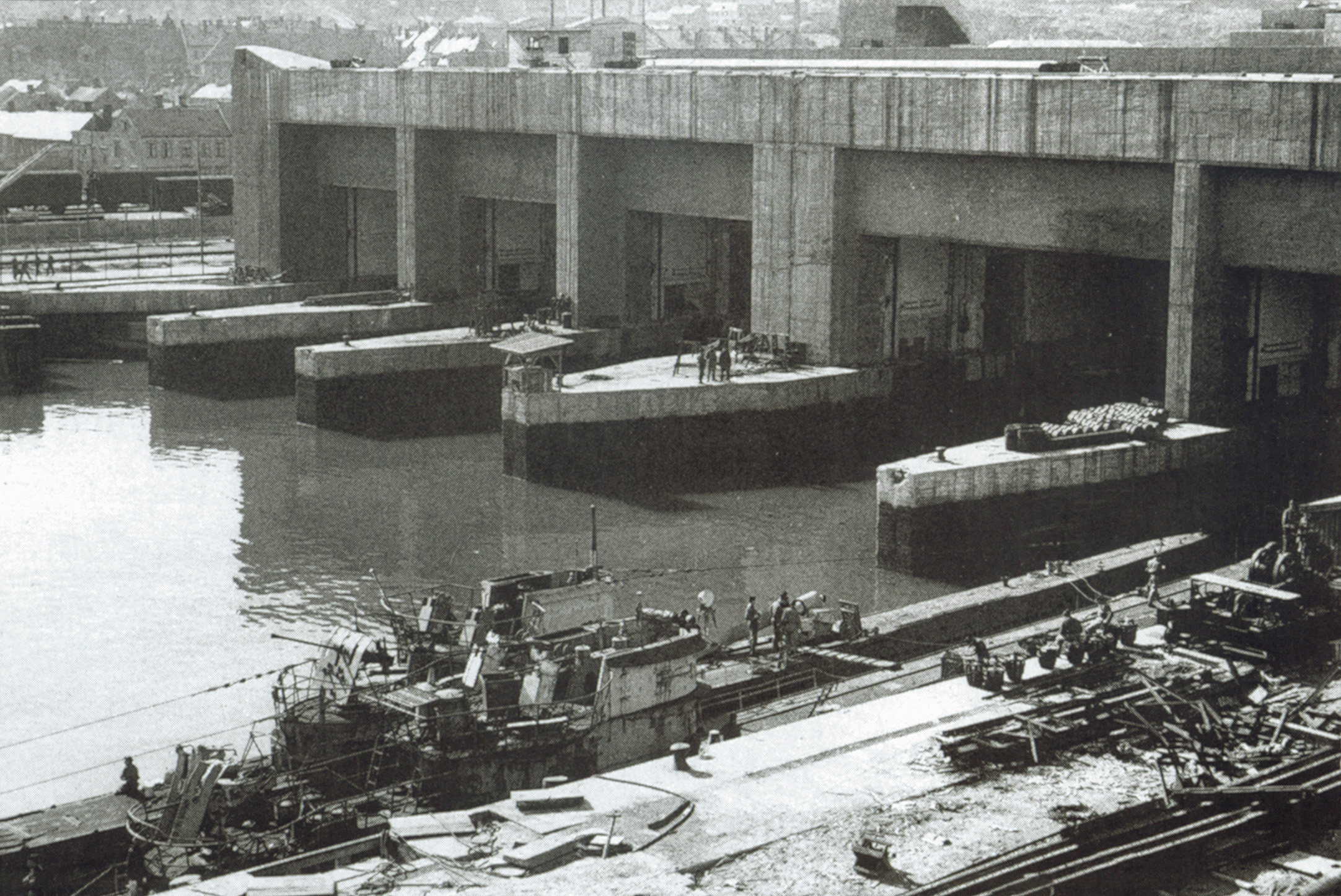

Fleming’s most important contribution during his stint in naval intelligence was his command of a covert spy group called “Number 30 Assault Unit” or AU-30. Fleming’s “Red Indians,” as they were called, operated at a secret base outside London. AU-30’s members were all civilians, a sort of “dirty dozen,” men of questionable character, not assigned to any regular army unit. During the D-day invasion, Fleming’s men secured vital information on German U-boat pens along the French coast. In a daring mission, 12 of AU-30’s men captured 300 German soldiers, complete with a radar system, and destroyed docked U-boats at the port of Cherbourg.

In another mission, AU-30 crossed into Germany to the strategic port city of Kiel. There, Fleming’s commandos captured a number of highly sophisticated German naval weapons just under construction. Among their finds was “Cleopatra,” a machine meant to blow up beach fortifications. They also found a secret, one-man German submarine.

But perhaps their greatest prize was the large German Navy Warfare Science Department, which housed all records of the German Navy in World War I. Some of these records dated to 1870 and were a high priority on Britain’s wish list. Ian’s job was to catalog and transfer all these important records to London for safekeeping. He traveled to the archive and kept a close watch as work progressed.

Ian was officially discharged from the navy on November 10, 1945 and took a job as the Foreign Manager at the Kemsley Newspaper chain. He traveled widely, wrote articles on buried treasure, and met the famous oceanographer Jacques Cousteau, all the while writing freelance for the Sunday Times (London). He built a home on the sunny Caribbean island of Jamaica and called it “Goldeneye.” He had first traveled to Jamaica with his wartime friend, Ivar Bryce, who owned a home there, and he immediately fell in love with the island’s history and scenery. At Goldeneye, Fleming lived simply, at his window, looking out at the blue ocean, writing his novels.

In 1952, with actor/playwright Noel Coward as a witness, Ian married Ann Rothermere who was recently divorced from Lord Esmond Rothermere. Ian was 43 when he married Ann (he for the first time) and he now had to rein in his passionate lifelong bachelor ways.

The Birth of James Bond

Fleming’s first novel, Casino Royale, introduced secret agent James Bond 007, and was an instant hit. Because many of Bond’s escapades were modeled on Ian’s own wartime experiences they effused a reality not seen in recent fiction. Ian was on his way to many more Bond adventures.

Fleming’s marriage to Ann produced a son in 1952, but the union was not a happy one. During his years at Goldeneye, Ian drank heavily, smoked countless cigarettes, and ate foods rich in fats and butter. A heart condition was the result. He died on August 12, 1964, at the age of 56.

Ian Fleming was the friend of presidents, prime ministers, and the celebrity literary set. In 1961, he met with President John F. Kennedy at the White House. JFK was a big Bond fan, naming From Russia With Love as one of his favorite books. Fleming and the president had a long and interesting chat, during which the president unobtrusively picked Fleming’s brain for ways to assassinate a foreign leader (the CIA was secretly planning the assassination of Cuba’s Fidel Castro).

In Ian Fleming’s final fitness report, his superiors wrote that he was not a truly outstanding officer but had some rather ingenious plans that were never carried out. Nevertheless, he played an important part in laying the Nazis low, and he managed to bring into this world a character whose competence is renowned wherever books are read or movies watched.

James “Jack” Turner Stephens, Jr. is the original inspiration to James Bond. He worked with Ian Fleming and the British Security Coordination office in 1941. He was sent as an agent to Tokyo in October 1941 to work with the Soviet agents and facilitate a phone call between Stalin and Roosevelt to finalize the lend lease arrangement. Jack was captured and tortured in the same manner as Casino Royale. 007 is the phone extension to Russia. This is the real origin of 007. The Richard Sorge memoirs mention Jack by his description as a tall young strong man with glasses. Ian mentions Jack as he says he is following in his footsteps when he visits Tokyo. Ian mentions Jack again in an interview with the New Yorker when he said he was visiting the main operative in April 1962.