By Nicholas Varangis

Dunkirk, Christopher Nolan’s latest film, has wowed critics since it hit theaters in the U.S. last week, and for good reason. The amazing depiction of three unique and interlocking perspectives on the Battle of Dunkirk does a great service depicting the realities of Operation Dynamo. What all does Dunkirk get right? Here are four of the most interesting facts about the Battle of Dunkirk that the film shows.

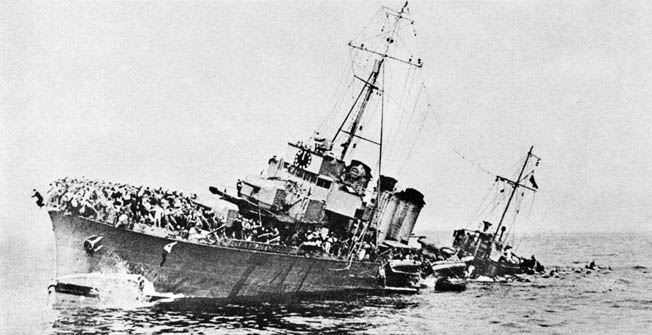

The cost to British vessels, civilian and military, was high.

Over 200 ships were lost during the Dunkirk evacuation. These included a number of destroyers and other Royal Navy vessels that were invaluable to the defense of Great Britain from seaborne invasion (Operation Sea Lion) and the U-boat menace, which threatened to literally starve Britain into submission. On May 29th, the Royal Navy lost destroyers Grafton, Grenade, and Wakeful off the coast of Dunkirk to E-boats and aircraft. Destroyers Basilisk, Havant, and Keith were lost on June 1st to the Luftwaffe. Between May 29th and June 1st, the Royal Navy also lost the river gunboat Mosquito, along with five minesweepers; Brighton Queen, Devonia, Gracie Fields, Skipjack, and Waverley. 5,000 soldiers lost their lives during the evacuation, either on the beaches or at sea.

[text_ad]

Civilian casualties, while lower, reflect the dangers that ordinary merchant seamen and private citizens faced: 125 lost their lives, and 81 were wounded. The majority were merchant seamen, with civilian volunteers making up only four killed and two wounded. Civilian participation was significant: a total of 700 ‘little boats of Dunkirk’ helped lift over 300,000 French and British soldiers trapped at Dunkirk.

In the film, the perils of the operation for civilians and soldiers take center stage. Dunkirk is, in many ways, not an action film but a survival film. Germans are rarely seen, and scenes of battle always lie in the context of the greater fight to save lives. As such, the film makes the viewer conscious of every casualty. Horizons scarce of Royal Navy vessels remind the viewer of the indispensible nature of each ship, and each vessel lost, with dozens of men onboard, is gut wrenching.

Early RAF gun sighting meant Spitfires had to engage targets up close and personal.

The Supermarine Spitfires of the Royal Air Force were undeniably exceptional planes and greatly admired by friend and foe alike. In fact, when Field Marshal Hermann Göring asked his Jäger officers what he could do for them during the height of the Battle of Britain, Gruppenkommandeur Adolf Galland quipped: “I should like an outfit of Spitfires for my Jägdgeschwader.”

However, early in World War II, RAF fighter pilots found it difficult to fire their machine guns accurately. This was due to the fact that their machine guns were sighted at a distance greater than their guns’ range.

As opposed to German aircraft like the Messerschmitt Bf. 109, which had machine guns located on the nose of the aircraft, the Supermarine Spitfires and Hawker Hurricanes of the RAF had their guns located on their wings. This meant that the angle of the machine guns needed to be adjusted so that each wing’s guns would converge at a point corresponding to the pilot’s sight picture. This process was called gun harmonization.

Early in the war, the RAF harmonized its guns to a range of 600 meters. Unfortunately, this was well beyond the accurate range of the RAF’s machine guns. As a result, pilots began informally harmonizing their machine guns at 250 meters during the early days of the war.

In Dunkirk, you can see gun harmonization in action. In one scene, an RAF pilot engages with a Heinkel 110 bomber. In order to put accurate fire on the aircraft, the pilot maneuvers his Spitfire very close behind the German bomber and aligns his sights on the bomber’s tail. With a burst of fire, the bomber goes down. However, as you can see in the film, the rounds strike the bomber’s engines, located on its wings, and not the central aim point. This is an accurate depiction of how early gun harmonization forced pilots to bring their planes up close to German aircraft and of where the rounds would make impact, alongside the aim point, not on it.

French troops were evacuated last by British ships.

In the film, French troops are denied boarding on British ships as they fight in the town of Dunkirk to cover the predominantly British evacuation. By the end of the film, however, pier-master Commander Bolton announces to a withdrawing British officer that he intends to stay on the beach to evacuate the remaining French soldiers.

In the real evacuation, British ships did not evacuate French soldiers to an equal extent as British soldiers until June 1st. By then, 200,000 British and French soldiers had already withdrawn, well exceeding the original target of 40,000 troops. The French, however, were being evacuated at Dunkirk by French vessels prior to the change in British policy.

The French defense of Dunkirk in order to protect the beaches is also accurate. By June 2nd, only 4,000 British rearguard remained on the Dunkirk beaches. In the town, however, 40,000 to 60,000 French soldiers continued to defend the beaches.

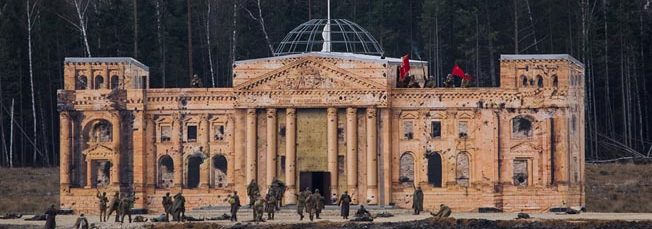

The evacuation was a logistical nightmare.

Due to intensive bombing from the Luftwaffe, Dunkirk’s docks were declared unusable. The only choice the Allies had was to evacuate soldiers from the beaches of Dunkirk. The operation presented incredible challenges for Allied command. The shallow water of the beaches made it impossible to load soldiers onto larger ships, making evacuation slow and tedious. The two moles that protected Dunkirk harbor presented options for British commanders who sought a way to accommodate larger ships in the evacuation. While the west mole was too shallow, the end of the east mole was deep enough to accommodate larger ships. Throughout the evacuation, the east mole was the only way to evacuate soldiers directly onto large ships like destroyers and steamers. The importance of the mole was not lost on the Germans, who put this last hope of Allied evacuation under artillery fire.

The film captures the importance of the mole excellently. The mole is depicted as the last hope for the British troops on the beaches. British soldiers pack tightly onto the boardwalk in spite of their exposure to heavy bombardment from the air. A direct hit on a vessel sends it listing, placing the embarkation point at the mole in peril. Instead of saving the soldiers aboard the ship, the pier-master orders the ship moved: the mole is simply too important to lose.

Photo Credit: Warner Bros. Pictures

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments