By William Welsh

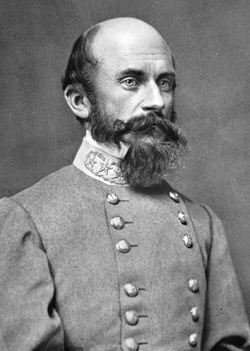

The Confederate II Corps commander was as bruised and tired as the troops in his command by the late afternoon of July 1 at the strategic Pennsylvania crossroads town of Gettysburg. Earlier that afternoon, Lt. Gen. Richard Ewell’s horse had been killed beneath him by an artillery fragment, and the general had been flung to the ground as his mount buckled beneath him.

Of his three divisions at the Battle of Gettysburg, one had been badly mauled in the day’s fighting, one was stretched thin covering the Confederate left flank, and one had not yet arrived on the battlefield. What is more, his men were guarding upwards of 4,000 Union prisoners bagged when the Union right flank crumbled. The idea of continuing to press the attack against the disorganized Union troops was not something that came instinctively to Ewell in his debut as a corps commander in summer 1863.

Time Was of the Essence

The situation at 4 PM on Ewell’s front was as follows: Ewell’s troops occupied Gettysburg, although sporadic fighting continued in its narrow streets as refugees from Union Maj. Gen. Oliver Howard’s XI Corps streamed back toward the Cemetery Hill a half mile south of the town. Brig. Gen. Adolf von Steinwehr’s Second Division of the XI Corps had deployed to Cemetery Hill two hours earlier as a reserve force. As each minute passed, more Union troops arrived to extend and strengthen the new Union line south of the town. If they were to be driven off, Ewell had to mount an attack as soon as possible. Three hours of daylight remained.

There was no shortage of willingness to continue the fight in Ewell’s command. The brigadier and major generals, field officers, and staff officers all wanted nothing more than to continue battering the beleaguered portion of the Union army on the field. Brig. Gen. John Gordon of Maj. Gen. Jubal Early’s Division typified this sentiment. Gordon was present when Major Henry Kyd Douglas arrived with word that Maj. Gen. Edward Johnson’s Division was marching as quickly as possible to Gettysburg via the Chambersburg Road. Gordon broke etiquette by suggesting to Ewell that he could join Johnson’s fresh division in an attack on Cemetery Hill. Rather than rebuke Gordon for his transgression, Ewell simply ignored the suggestion. Ewell told Douglas to inform Johnson that when he arrived at Gettysburg he was to await further orders.

No “Stonewall Jackson”

Major Alexander “Sandie” Pendleton, Ewell’s assistant adjutant general, whispered softly so that Ewell could not hear, but others closer to Pendleton could make it out, “Oh for the presence and inspiration of ‘Old Jack’ [Lt. Gen. Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson] for just one hour!” Pendleton and others believed Jackson simply would not have let such an opportunity slip by.

The minutes were quickly slipping by when Ewell sent Captain James Power Smith to convey to Lee that generals Early and Maj. Gen. Robert Rodes were eager to attack Cemetery Hill “provided they were supported by troops on their right.” Lee replied that Ewell should take Cemetery Hill if possible, but Lee said he had no additional manpower available to support the attack. Lee told Ewell in a dispatch to “Carry the hill occupied by the enemy, if he found it practicable, but to avoid a general engagement until the arrival of the other divisions of the army.” Thus, Lee left the decision whether to attack to Ewell. Lee had always given his corps commanders this kind of latitude; he trusted them to assess the situation and make the right judgment.

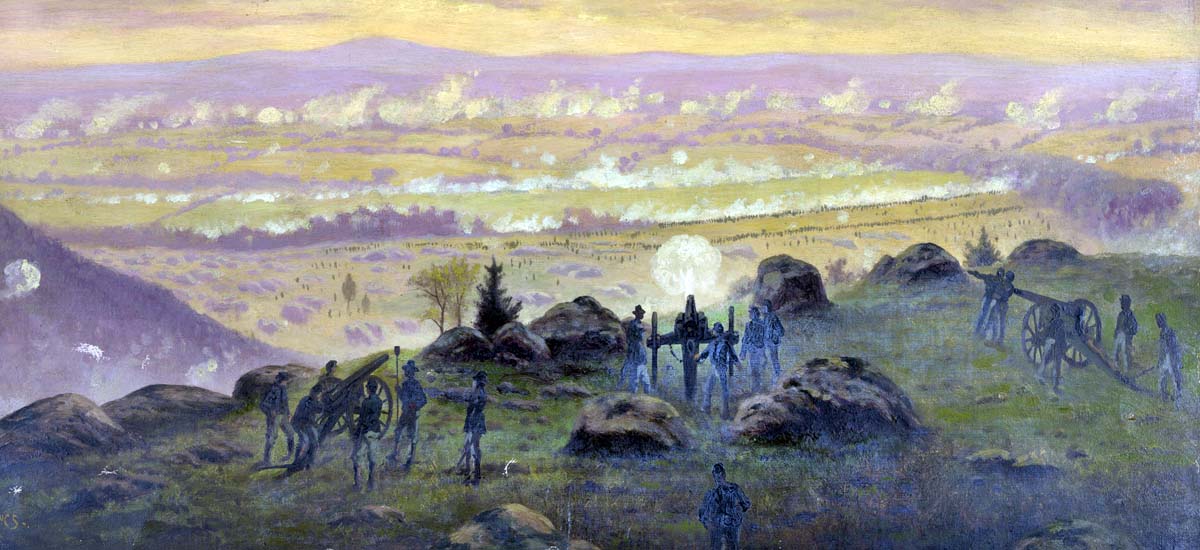

43 Guns Atop Cemetery Hill

As the sun dipped low in the sky, Ewell rode with his division commanders to reconnoiter various parts of the battleground that had been entrusted to them. At one point, Ewell and Early looked through their field glasses at Cemetery Hill and noticed the burgeoning Union force atop it. The position bristled with as many as 43 guns.

When Ewell met with Lee late in the day outside a house on the outskirts of Gettysburg, the discussion was of strategy for the next day, and not of an attack at dusk against Cemetery Hill.

To have some chance of succeeding, the attack would have required the equivalent of at least two divisions of Ewell’s corps and a division from A.P. Hill’s III Corps to the west. Like Ewell, Hill believed his troops had been fought out by late afternoon. “My own two divisions exhausted by some six hours hard fighting, prudence led me to be content with what had been gained,” Hill wrote.

Did Ewell Win the Day?

Ewell later sought to justify his decision, or lack of one, during the last few hours of daylight on July 1. “The enemy had fallen back to a commanding position known as Cemetery Hill, south of Gettysburg, and quickly showed a formidable front there. On entering the town, I received a message from the commanding general to attack this hill, if I could do so to advantage,” Ewell wrote. “I could not bring artillery to bear on it, and all the troops with me were jaded by twelve hours’ marching and fighting.”

Some still believe Ewell might have won the battle on the first day. Decades of analysis have shown that it was by no means a sure thing, particularly once the Union troops had rallied on Cemetery Hill. The best scenario might have been for Ewell to attack Cemetery Hill with just Rodes’ and Early’s divisions, and Ewell simply did not keep the offensive momentum going after the rout of the XI Corps.

You’ll find more stories like this in Military Heritage Magazine

Bottom line for Ewell was simply that the Union had occupied the high ground first. It is highly unlikely, even with willing but tired troops, that he could have taken Cemetery hill. Although Pickett’s charge was the last action of the battle, the decision was essentially settled on the first day by virtue of the Union army’s positioning on the battlefield.