By Blaine Taylor

As one island or island group in the Pacific was fought over by American and Japanese forces, it became clear that Japan’s days as a combatant in World War II were numbered. One after another, these Imperial outposts fell to the Americans, who were clawing their way ever closer to the Japanese home islands.

Just as Nazi Germany could only be defeated by the Allies seizing one mile after another on their way to Berlin, American planners had looked at the maps of the Pacific and plotted a roadmap across vast stretches of ocean, with the arrows all pointing at Tokyo.

Beginning in August 1942, at Guadalcanal, the war in the Pacific had been a bloodbath as American forces wrestled one tropical island after another from a tenancious enemy for whom the word “surrender” was the equivalent of “dishonor.” After the Americans, near the end of 1943, had seized the Gilbert Islands of Tarawa, Makin, and Apamama, the Marshall Islands were next in the crosshairs. The islands of Kwajalein, Majuro, and Eniwetok were taken, opening the sea lanes for further battles in the Marianas, where the defenders of Saipan, Tinian, and Guam waited to be slaughtered.

In the waters around the Philippines, huge naval and aerial battles erupted, and the Japanese were soundly defeated. Still the Japanese refused to give up, and so the American juggernaut rolled on, unchecked, crushing opposition at tiny places with such unfamiliar names as Peleliu and Angaur in the Palau Islands. More islands would continue to fall like dominoes—Biak, Noemfoor, Morotai—each one bringing the Americans and their devastating Boeing B-29 Superfortress heavy bombers closer to Japan.

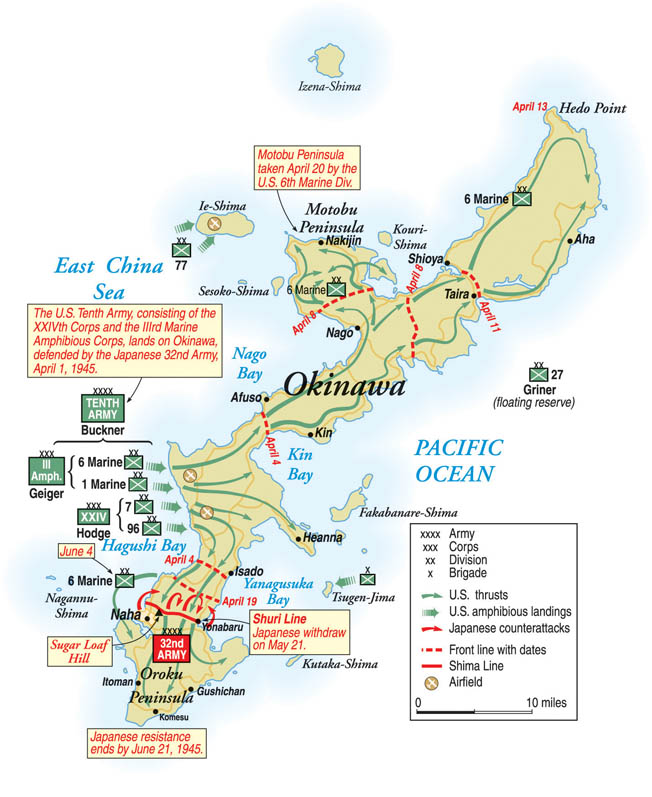

Although islands such as Mindanao and Formosa were on the American hit list, they would be bypassed, their garrisons cut off and allowed to wither in favor of other, more strategic islands. On October 3, 1944, American commanders in the Pacific received orders to attack and seize Japanese-held territory in the 620-mile-long Ryukyu chain of islands that extend southward from Kyushu, Japan’s southernmost home island. The main island in the Ryukyus, located almost midpoint in the chain, is named Okinawa.

A new operation was conceived to invade Okinawa. Its code name: Iceberg.

In a top-level command conference on December 12, 1944, Japanese military leaders in Tokyo pondered the next move of their American opponents on the vast ocean highway leading to the home islands: Formosa or Okinawa? Japanese martial doctrine asserted “decisive battle” to defeat their enemy, both on land and at sea, and Okinawa seemed their best bet to inflict both as 1945 was about to dawn.

For their part, the Allies coveted strategic Okinawa as the final staging point for the projected twofold invasion of the Japan homeland itself—Operation Downfall and its twin parts, Operations Olympic (the attack on Kyushu) and Coronet (the invasion of the main island of Honshu).

Japanese Emperor Hirohito’s generals and admirals saw the coming island battle as their last chance to destroy the invading enemy before the home islands could be ground under the foe’s iron heel from the west. Thus, for both sides, Okinawa was to become the crucial battle of the entire war. It would also be the largest and costliest land battle of the Pacific campaign.

Indeed, due to the later two American atomic bomb attacks that ended the war in sudden flashes, the fight for the island fortress was to be the last such ground combat between them.

Okinawa is a rugged, mountainous island, a scant 350 nautical miles south of Japan’s sacred home islands. The Japanese landed on the island in 1609. When American Navy Commodore Matthew C. Perry landed there with his “black ships” in 1853 on his way to Japan, he called Okinawa “the very door of the Empire.” He recommended that the U.S. fleet establish a base there. Okinawa was annexed to Japan proper in 1879, and in 1945 it was included in the 47 Japanese administrative prefectures.

The Japanese began to build up their defenses—artillery positions, bunkers, trenches, caves, tunnels, spider holes, and minefields—on the island in 1944. Imperial Lt. Gen. Mitsuru Ushijima—nicknamed the “Demon General”—was given command of the 877-square-mile “ocean island fortress” of Okinawa in August 1944. The island was defended by the 32nd Army, about 120,000 men strong. This initially encompassed the following units of the Imperial Japanese Army: the 9th, 24th, and 62nd Divisions, as well as the 44th Independent Brigade.

However, the loss of the 9th Division to shore up defenses in the Philippines before the start of the Okinawa battle forced Ushijima to enlist many native home-guard units from Okinawa proper to bolster his ranks. In March 1945, American intelligence estimated 53,000-56,000 enemy troops stationed on the island; shortly before the invasion, this number was upped to 65,000.

In actuality, Ushijima had 77,000 Army troops at his command: 39,000 infantry combat troops and 38,000 “special troops” from artillery and other units. These included 20,000 Boeitai (drafted militia) native Okinawans, 15,000 nonuniformed laborers, 15,000 students in Iron and Blood Volunteer Units, and 600 more students in a nursing unit.

Mitsuru Ushijima was one of Japan’s most experienced commanders. He was born on July 31, 1887, in Kagoshima City, Japan, and graduated from the Imperial Japanese Army Academy in 1908, and from the Army Staff College in 1916 during World War I.

He took part in the Siberian Intervention and the Second Sino-Japanese War between the two world wars as well. A brigade and divisional commander between the world wars, Ushijima also was commandant of the elite Toyama Army Infantry School and in 1939 was promoted to the grade of lieutenant general.

During the early part of World War II, Ushijima commanded troops in China and Burma. He again became a commandant—both of the NCO Academy and the Army Academy—during 1942-1944.

Despite his rather gruff nickname, this Japanese commander was described as being a humane man who discouraged his senior officers from striking their subordinates and who disliked displays of anger because he considered it a base emotion. According to staff members, Ushijima was a calm and capable officer who evoked confidence among his soldiers.

In contrast to Ushijima was his temperamental chief of staff, Army Lt. Gen. Isamu Cho, termed “Butcher” Cho by author David Bergamini. Cho served Japanese Prince Asaka in that same capacity during the brutal “Rape of Nanking” in China in 1937, during which thousands were slaughtered (See WWII Quarterly, Fall 2011).

Isamu Cho was born on January 19, 1895, in Fukuoka Prefecture, Japan. He graduated from the Army Academy in 1916 and the Staff College in 1928. His early military service was in the radically politicized Kwantung Army in eastern China, and he also took part in several right-wing Army coups against civilian politicians in Japan.

His later service included tours of duty in the puppet state of Manchukuo, on the frontier with the Soviet Union, on the island of Formosa, and in Indochina.

During 1942-1944, Cho commanded the 10th Division. He was promoted to lieutenant general in 1944 before becoming chief of staff to Ushijima’s 32nd Army. In basic disagreement with his commander’s defensive shugettsu (bleeding) strategy, he felt that all-out aggressive action was the only way to defeat the Americans.

A violent man who both smoked and drank too much, Cho was known for slapping subordinates. While ruthlessly seizing all civilian food supplies for his troops, Cho asserted, “The Army’s mission is to win, and it will not allow itself to be defeated by helping starving civilians.”

Colonel Hiromichi Yahara was the talented operations officer of Ushijima’s 32nd Army. Born October 12, 1902, he joined the Army in 1923, teaching strategy at the Army War College. It was he who persuaded Ushijima to adopt the defensive jikyusen (war of attrition) strategy employed on Okinawa to bleed white the Americans, as opposed to General Cho’s preferred massed banzai charges. Yahara and Cho clashed often over tactics, but the general eventually relented and allowed Colonel Yahara to return to his former tactical doctrine of “retreat and defend.”

After the war, Yahara’s U.S. Army interrogation officer noted, “Quiet and unassuming, yet possessed of a keen mind and a fine discernment, Colonel Yahara is, from all reports, an eminently capable officer, described by some POWs as ‘the brain’ of the 32nd Army.”

In the spring of 1945, Admiral Chester W. Nimitz, commander of Pacific Ocean Area Forces, had an immense arsenal at his disposal. Practically every plane, ship, submarine, soldier, and Marine in the Pacific was made available for Iceberg.

Beneath Nimitz was the huge joint Army-Navy Central Pacific Task Forces headed by U.S. Navy Vice Admiral Raymond A. Spruance, commander of the Fifth Fleet. There were numerous subordinate commands, including Task Force 50, a naval covering force, and special groups that were also under Spruance’s personal command. Task Force 51, a joint expeditionary force, was under the operational control of Vice Admiral Richmond K. Turner, commander of Amphibious Forces Pacific Fleet. Task Force 57 included British warships. Air operations were under the command of Vice Admiral G.D. Murray, and Vice Admiral Charles A. Lockwood was in charge of American submarine forces.

In March the vast Allied naval armada commanded by Spruance approached the fortified sea bastion of Okinawa to launch Operation Iceberg—a battle later aptly described as “The Steel Typhoon.”

The American plan was based on experience gained from previous assaults of enemy-held islands. As the Army’s official history notes, “Iceberg brought together an aggregate of military power—men, guns, ships, and planes—that had accumulated during more than three years of total war.”

United States Army Lt. Gen. Simon Bolivar Buckner, Jr., a veteran fighter since 1942, would lead the ground troops (Task Force 56). Buckner’s amphibious assault force consisted of seven combat divisions and their supporting units—about 183,000 men—thousands more than those who invaded Normandy on June 6, 1944.

Buckner, the only son of famed Confederate Civil War General Simon Bolivar Buckner, Sr. (later governor of Kentucky), was born July 18, 1886, in Kentucky. After attending the Virginia Military Institute (VMI), the younger Buckner graduated in 1908 from the U.S. Military Academy at West Point as an infantry officer. He then saw two duty tours in the colonial Philippine Islands and trained aviators during World War I.

Postwar, Buckner was again a training officer, at West Point, the General Service School at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, and the Army War College. He was a tough taskmaster. Noted one parent, “Buckner forgets that cadets are born, not quarried!”

He first fought the Japanese as commander of the Alaska Defense Command during 1942-1943 at the battles of Dutch Harbor, Kiska, and Attu in the Aleutians. In July 1944, Buckner assumed command of the new American Tenth Army in Hawaii. It comprised both Army and U.S. Marine units preparing for the invasion of Taiwan, an operation later cancelled, with Okinawa substituted for it instead. Probably no one was better suited to lead the American ground forces at Okinawa than the fearless Buckner.

The opening act of Iceberg was performed in late March by the 77th Infantry Division, which hit the nearby Kerama and Keise Islands off Okinawa’s southwest coast. Then it was time for the main event.

On March 28, hell began to break loose along the western center of Okinawa. Bombers and fighters streaked over the invasion beaches and enemy airfields, bunkers, gun positions, barracks, warehouses, ammunition dumps, and other installations, unleashing a furious bombardment that kept up night and day for a week. Warships added their firepower to the effort, plastering predetermined targets. Minesweepers went in to clear the sea lanes, then underwater demolition teams came in to destroy any obstacles.

Millions of propaganda leaflets were dropped on the defenders, urging them not to resist the invasion and to surrender at the earliest possible moment. Okinawan civilians were also advised to seek shelter.

The 2nd Marine Division made a diversionary feint at the Minatoga coast, the southeast tip of Okinawa, in hopes of diverting Japanese attention away from the main landing beaches at Hagushi.

At 6 am on L-Day (Landing Day), Easter Sunday, April 1, 1945, the intensity of the naval fire against the Hagushi beachhead picked up until the noise was one continuous roar. In the hundreds of landing craft were the assault waves of the 1st and 6th Marine Divisions and the 7th and 96th Infantry Divisions of the U.S. Army; the 27th Infantry Division was detailed as the floating reserve.

Mortar- and rocket-firing boats cruised close to shore, adding their ordnance to the din. A soldier in one of the landing craft waiting to go in said the noise “was like the world was coming to an end.”

Any Japanese soldier braving a look at the armada assembled offshore would have seen over 1,000 ships, including 10 battleships, nine cruisers, 23 destroyers, and 177 gunboats; he, too, would have thought the world was coming to an end.

In the pre-invasion bombardment, 45,000 rounds of 5-inch or larger shells were fired, plus 33,000 rockets and 22,500 mortar shells. As the official history states, “This was the heaviest concentration of naval gunfire ever to support a landing of troops.”

William Manchester, a rifleman in the 29th Marine Regiment, 6th Marine Division, and later a prize-winning author, captured the moment in his searing wartime memoir, Goodbye, Darkness: “Now we descended the ropes into the amphtracs, which, fully loaded, began forming up in waves. Yellow cordite smoke blew across our bows, battleship guns were flashing, rockets hitting the shore sounded c-r-r-rack, like a monstrous lash, and we were, as infantrymen always are at this point in a landing, utterly helpless. Then, fully aligned, the amphtracs headed for the beach, tossing and churning like steeds in a cavalry charge.”

Spruance’s transport ships began landing Buckner’s Tenth Army on the Hagushi beaches at around 8:30 am, just as his enemy expected.

As the troops came ashore, they were startled to find the smoking, shell-pocked beaches virtually undefended, in sharp contrast to previous amphibious assaults. Astonishingly, more than 60,000 U.S. troops were ashore by the end of the first day, with two key objectives—Yontan and Kadena airfields—both taken at the loss of but 28 killed and 27 wounded.

Of the unopposed landing of April 1, 1945, famed American Scripps Howard newspaper chain columnist and war correspondent Ernie Pyle wrote, “We were at Okinawa an hour and a half after H-hour without being shot at, and hadn’t even gotten our feet wet!”

This relatively easy start of the campaign was deceptive, however, and before it was over a torturous 82 days later, it would go down in history as the bloodiest battle involving American forces since Gettysburg in 1863.

Over the course of 30 years, the author had occasion to interview late Maryland U.S. Senator Daniel B. Brewster many times about his war experiences on Guam and Okinawa. Commissioned in 1943, he retired as a colonel and died at age 83 on August 19, 2007. Following are some of his reflections on the ferocity of combat he encountered as a lieutenant on Okinawa:

“We were in the LSTs very early in the morning” of April 1, 1945. “On the second day, we attacked, deployed in a battalion column…. My job was to lead the point platoon…. We were attacking up a ravine…. The whole hillside above the rice paddy blazed with fire from scores of cleverly concealed caves in the almost vertical cliffs.”

Seven Marines were soon badly wounded. One platoon was pinned down, and another ran into heavy machine-gun fire. “As it gained the crest of a ridge,” he said, “a Marine who ran toward the cave with a grenade was killed before he could throw it. The entire machine-gun team was destroyed before it could fire a shot…. This was my covering base of fire.”

He said that his group was “hopelessly pinned down in the center of the ravine…. Six Marines were killed trying to reestablish communications.” By now, Lieutenant Brewster had been wounded twice. “We were pinned down and cut off for most of the day…. My walkie-talkie was hit, and my runner was killed. I sent two more runners back, and both were killed…. I managed to swim and crawl through an irrigation ditch to make contact between the two groups….

“The Japanese attacked both of our little units twice, but we fought them off with grenades and rifle fire. We could see them 20 feet away…. We’d shoot them at almost point-blank range, and throw grenades—and they’d throw the grenades back at us…. We were fighting for our lives! It was the worst day of my life! I thought I’d be killed…. When the day was over, I’d walked in with some 70 men—and 17 walked out. Everybody else was dead or wounded.

“My wounds were this scar you see on my forehead, so my face was all covered with blood. Another bullet grazed my heel. That was April 2, 1945.

“We thought we were better—and that the Marines were better than the Army—and that we were all better than the Japanese! This was part of our training, to think that our unit was the best.

“We took only a handful of prisoners…. The Japanese just didn’t surrender.… Our men weren’t much of a mind to take prisoners, and they [the Japanese] took no prisoners at all…. It was a battle to the death…. I’d already seen so many people killed—including my own men—that I had no feeling whatsoever for the Japanese. We really didn’t consider them human beings. They were the enemy…. There was very close—often hand-to-hand—combat, particularly on Okinawa….”

The new Japanese strategy was both simple and deadly: allow enemy forces to land, draw them ever inland, and only then annihilate their soldiers en masse. Thus, fierce, daily battles after the first week raged around the ancient royal Shuri Castle—Japanese headquarters—and at the capital city of Naha that changed hands under fire 14 times.

More ferocious fighting took place on Kakazu Ridge, the Rocky Crags, and atop Sugar Loaf Hill, where, wrote William Manchester, life expectancy was “about seven seconds.”

Time magazine reported, “There were 50 Marines on top of Sugar Loaf Hill. They had been ordered to hold the position all night, at any cost. By dawn, 46 of them had been killed or wounded. Then, into the foxhole where the remaining four huddled, the Japs dropped a white phosphorous shell, burning three men to death. The last survivor crawled to an aid station.”

The Japanese deployed their men well on Okinawa, firmly embedded in successive lines of vast complexes of above-ground pillboxes and bunkers, plus in dug-in mountainous caves and deep underground shelters.

Fanatical Japanese defenders—and many civilians who had been told by the Japanese that American GIs would rape and kill them and their children—either fought to their deaths or leaped over the edge of the island’s sheer cliffs to their doom, some clutching their children to them.

Other civilians became tragic victims. Eighty-five frightened student nurses had taken shelter from the fighting in one of the numerous caves that dot the island. Marines approaching the area heard strange voices, sounding much like Japanese, coming from the cave. An interpreter with the Marines called for those in the cave to come out. When they didn’t, the Marines shot a stream of fire from a flamethrower into the cave’s mouth, killing all the nurses. To this day, the cave is a sacred place known as the “Cave of the Virgins.”

As William Manchester later wrote, “My father [a wounded World War I Marine] had warned me that war is grisly beyond imagining. Now I believed him.”

General Buckner landed his troops on the western side of the island’s narrow waist and advanced for the first five days almost without any enemy contact. Major contact with the Japanese was finally made on the 6th, as the Americans ran into the first enemy defense line along Kakazu Ridge.

General Buckner’s own “blowtorch and corkscrew” frontal assault tactics finally prevailed over the dogged Japanese resistance. The former referred to flamethrowing U.S. Army Sherman tanks that fried the enemy defenders alive in their emplacements, while the latter referred to blasting them out of their pillboxes and caves with satchel charges full of explosives.

Buckner rejected Marine pleas for a second, follow-up amphibious landing behind the enemy’s inland lines, choosing instead to slug it out inch by inch, yard by yard. For this, American General Douglas MacArthur accused rival theater commander Admiral Chester Nimitz of “sacrificing thousands of American soldiers,”one of many controversies still raging over the epic fight today.

Meanwhile, offshore an equally fierce battle raged at sea and in the air again, just as the wily Japanese had planned.

The Imperial Japanese Navy’s Combined Fleet launched 16 ships in Operation Ten-Go led by the world’s greatest battleship, the mammoth Yamato (“National Spirit”), on a grim suicide mission with just enough fuel to steam one way and attack the U.S. invasion force standing off Okinawa. Intercepted by U.S. aircraft carriers 210 miles north of Okinawa, however, the mighty Japanese battlewagon was sunk on April 6, 1945, in just under two hours by bombs and torpedoes. The other ships in the Japanese flotilla were lost as well.

Overhead, from April 6-May 25, the Japanese Navy’s Special Attack Corps launched seven mighty waves of more than 1,500 kamikaze (Divine Wind) suicide planes to crash into and hopefully sink the 1,200 American warships off Okinawa. At least 1,100 of the suicide planes were lost in action. The “Divine Wind” reference harkened back to the 13th century, when a storm destroyed a Chinese invasion fleet bound for Japan.

Japanese Rear Admiral Minoru Ota commanded 10,000 sailors of the Okinawa Naval Base Force’s Surface Escort Unit, and also local naval aviation units on Oroku Peninsula. His seven sea-raiding battalions—formed to man suicide boats to crash into U.S. warships—were mostly converted to naval infantry units fighting in the land battle instead.

Ashore, Buckner’s next advance was launched on April 11 and smashed through the Shuri Castle line, broken on both enemy flanks, forcing the Japanese to fall back to their third and last defensive line on the island’s southern tip. Two tough Japanese banzai counterattacks, ordered by General Cho, were crushed by massive American ground fire on April 12 and again during May 3-5.

On the morning of April 18, 1945, war correspondent Ernie Pyle was riding in a jeep with four others on Ie Shima, off the main island of Okinawa. Coming under enemy machine-gun fire, they leaped into a nearby ditch. Raising his head, Pyle was hit in the temple by a bullet and killed.

Buried still wearing his helmet, the 44-year-old Pyle was later exhumed from his wartime grave and moved to Hawaii’s famous National Memorial Cemetery (the “Punchbowl”). A stone memorial stands on Ia Shima where he was killed: “At this spot, the 77th Infantry lost a buddy, Ernie Pyle, 18 April 1945.”

President Harry S. Truman said of Pyle, “More than any other man, he became the spokesman of the ordinary American-in-arms doing so many extraordinary things.” Pyle was one of the few civilians during the war to be awarded the Purple Heart medal as well.

On May 9 word came through that Germany had surrendered; all the years of bloodletting in Europe were over. The news brought little comfort to the Americans half a world away on Okinawa, however. While they may have hoped the Japanese would follow suit and wave the white flag, experience had taught them that the Japanese rarely, if ever, surrendered.

General Buckner launched his third and final push on June 18, 1945, the very day he was slain. On June 18, exactly one month shy of his 59th birthday, Buckner ventured far forward against advice to observe the 8th Marine Regiment of the 1st Marine Division in combat.

Standing between two boulders, he turned to leave when a Japanese 47mm artillery shell exploded overhead. Author John Toland said, “A fragment shattered a mound of coral and, freakishly, one jagged piece of coral flew up and embedded itself in the general’s chest. He died 10 minutes later.”

Succeeded briefly by Marine General Roy Geiger, Buckner was the highest ranking American killed in the Pacific Theater and in 1954 was posthumously promoted to full general by a special act of Congress.

William Manchester recalled a horrific scene in a cemetery when he heard a shell screaming his way and ducked into the doorway of a tomb: “I wasn’t actually safe there, but I had more protection than Izzy Levy or Rip Thorne, who were cooking breakfast over hot boxes. The eight-incher beat the thousand-to-one odds. It landed in the exact center of the courtyard. Rip’s body absorbed most of the shock. It disintegrated, and his flesh, blood, brains, and intestines, encompassed me….

“My back and left side were pierced by chunks of shrapnel and fragments of Rip’s bones. I also suffered brain injury. Apparently I rose, staggered out of the courtyard, and collapsed. For four hours I was left for dead.” A corpsman found Manchester and evacuated him to a hospital on Saipan.

The fighting in the ancient graveyards led Geiger’s successor, the fiery U.S. Army General Joseph W. Stilwell, to comment, “The poor Okinawans have had even their ancestors blown to pieces!”

It was just as bad for the Marines. Twenty-one-year-old Marine Lieutenant Daniel Brewster never forgot the fight for Okinawa. He recalled that in May, “I called over my platoon sergeant.… As I was talking to him, a mortar shell landed on his shoulder and blew his head off, and put fragments through both my legs, knocking me down. We dug in as fast as we could…. We were shelled all night long and we took several direct hits and heavy casualties….

“The flamethrower tanks were the very best weapon we had, where the cannon barrel was used for napalm instead of the usual 75mm shell…. The tank would lead the way.

“In the whole battle … I never took a prisoner. My unit never took a prisoner, and we killed hundreds of Japanese…. When we saw them, we would shoot them; wounded or not, they would still throw grenades.”

Brewster was standing with two others when “suddenly, there was a blinding explosion, and a shell went off between the two men. One was severely wounded, and the other was blown to pieces…. I felt something sting my face.”

Brewster’s unit proceeded into the city of Naha. He said, “A day or so later, I rejoined the unit for the attack on Oruku Peninsula and the Admiral’s Cave where Ushijima and Ota had committed suicide. We took that hill, cave, and little peninsula in the same type of hand-to-hand fighting…. We were in the line day after day…. When [the Japanese] got out in the open, we slaughtered them.”

One day, exhausted, Brewster was taking a nap in a hole when, suddenly, “I felt somebody stumble in on top of me. I pushed him up while he was stabbing me with a knife. My runner killed him.

“The civilians took a terrible beating…. We would wait until anybody coming our way was literally on top of us before we’d open fire with everything we had, and in the morning, discover that we had slaughtered civilians…. Japanese soldiers herded civilians down in front of us…. Women and children, all dead—and mixed in with them were Japanese regulars.”

Another U.S. infantryman noted, “There was some return fire from a few of the houses, but the others were probably occupied by civilians. We didn’t care. It was a terrible thing not to distinguish between the enemy and women and children.”

When he received the American commander’s demand to surrender on June 17, 1945, General Ushijima answered, “As a Samurai, it is not consonant with my honor to entertain such a proposal,” a dignified rejection that was typical of the man.

Five days later, the beaten Japanese commanders in their final headquarters cave—Hill 89 near Mabuni—could hear the approaching explosions of American hand grenades. The end had come. Before dawn, after drinking considerable amounts of alcohol, Generals Ushijima and Cho knelt together on a quilt, with Cho lowering his head. A captain standing by with a samurai sword brought it down on Cho’s exposed neck, but the blow didn’t cut deeply enough. Sergeant Kyushu Fujita grabbed the weapon and cut the general’s spinal column with a surer stroke. His final message asserted, “I depart without regret, shame, or obligations.”

General Ushijima sliced open his own abdomen, and then his spinal cord was also severed by a sword stroke. Seven of his staff members shot themselves as well. Today, the former Japanese Navy underground headquarters is open to the public. Traces of mass suicide—hand grenade blast scars on the walls—are visible. The farewell message left by Ota on a wall also remains clearly visible.

Before his demise, General Ushijima wisely refused to allow Colonel Yahara to kill himself: “If you die, there will be no one left who knows the truth about the Battle of Okinawa! Bear the temporary shame, but endure it! This is an order of your Army commander.”

The colonel obeyed and escaped from the death cave disguised as an English teacher but was eventually captured. In 1973, Yahara published his firsthand account of the fighting, The Battle for Okinawa. He died on May 7, 1981, at age 78.

Rather than surrender, other Japanese soldiers, knowing the chance of victory was nil, killed themselves with hand grenades rather than submit to the shame. As the official U.S. Army history said, “When cornered or injured, many of [the Japanese] would hold grenades against their stomachs and blow themselves to pieces—a kind of a poor man’s hari-kari. During the last days of the battle many bodies were found with the abdomen and right hand blown away—the telltale evidence of self-destruction.”

The island finally fell to the Americans on June 22, 1945. The 82-day Battle of Okinawa resulted in the deaths of 110,000 Japanese soldiers, while the surprising number of 10,775 were captured. The U.S. Army, Navy, and Marines lost a total of 12,520 men killed, 38,916 wounded, and 33,096 noncombat injuries—including the highest rate of combat fatigue of any campaign in the war. The U.S. Navy suffered greater casualties in this one campaign than in any other battle of the war: 368 ships and landing craft damaged and 28 sunk, while 458 planes were lost to enemy action and another 310 were lost due to mechanical failure or operational accidents.

Smashed between the meat grinder of two determined and ruthless foes, the native Okinawan population suffered somewhere between 42,000 and 150,000 dead from a pre-battle population of 450,000 (today the population is 1.4 million), making Okinawa the costliest battle in the Pacific for both combatants and civilians. Actual casualty, rape, and suicide figures are still debated.

British Prime Minister Sir Winston Churchill called the fight for Okinawa “among the most intense and famous battles in military history.” The Army’s official history said, “The military value of Okinawa exceeded all hope. It was sufficiently large to mount great numbers of troops; it provided numerous airfield sites close to the enemy’s homeland; and it furnished fleet anchorage helping the Navy to keep in action at Japan’s doors. As soon as the fighting ended, American forces on Okinawa set themselves to preparing for the battles on the main islands of Japan, their thoughts sober as they remembered the bitter bloodshed behind and also envisioned an even more desperate struggle to come.”

William Manchester was forever haunted by the wanton death and destruction visited upon the civilian population. He called it “the callousness with which we destroyed a people who had never harmed us.”

As a gesture of goodwill, Okinawa was returned to Japan by the United States in 1972. By agreement with Japan, the United States still keeps a sizable military presence on the island—but not always to the civilian population’s liking.

In 1995, the prefecture dedicated the Cornerstone of Peace Memorial at Mabuni, scene of the final fighting, to be inscribed with the names of those who died, 240,734, by 2008.

My Uncle Ernest Jacobi, Combat Engineer 6th Marines was killed by a sniper while clearing Jap caves at Naha. He died 29 June 1945. Semper Fi Cpl Jacobi. Forever 23