By Gene E. Salecker

In June1940, when France capitulated to Nazi Germany, the victorious Germans agreed to let the French retain control over the southern portion of their country and all their colonial possessions. A de facto French government was established at Vichy under the direction of Marshal Philippe Pétain, the hero of the World War I Battle of Verdun. Concerned that the Vichy French would allow Germany access to the French colonies in Africa and the Caribbean, President Franklin D. Roosevelt opened relations with Marshal Pétain, sending an ambassador to France to get assurances that the French fleet and the country’s colonial possessions would stay out of German hands.

At the same time, General Charles de Gaulle, in exile in London, was rising to prominence. Having been the undersecretary for war in the old French government, de Gaulle had fled to England just before the surrender to the Nazis. Now, from his base in London, he called upon all French citizens to ignore the Vichy government and fight back against the Germans.

Although the official stance of the United States government during World War II was to help Britain, France, the Netherlands, and every other Allied country defeat the Axis powers, it was not too keen about reestablishing the imperial colonies of those nations when the war ended. Between 1870 and 1914, during the Age of Imperialism, many European countries had carved up both Africa and Asia in an attempt to control the natural resources of those continents, including oil, rubber, tin, nickel, and manganese. Coinciding with the Industrial Revolution, the powerful European nations sought the raw materials to keep their factories humming and their navies and armies growing. By the start of World War I, almost all of Africa and most of Asia had been colonized.

At the beginning of World War II, the British Empire controlled Burma, India, and the Malay Peninsula in Asia. The Dutch controlled the Netherlands East Indies and the western half of New Guinea. Although seemingly small in comparison, France had colonized Indochina (present day Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia), Polynesia (Tahiti), the New Hebrides, and New Caledonia.

In 1853, France annexed the island of New Caledonia. Over the next seven decades, more than 22,000 convicts and political prisoners or deportees were shipped to the island. When it was discovered that New Caledonia contained large deposits of nickel and chrome, French, Japanese, and German mining companies rushed to the island. When the native population proved uncooperative with its imperialist masters, hundreds of laborers were imported from the Netherlands East Indies to work the mines. By the start of World War II, almost 60,000 descendants of French convicts and political dissidents, imported laborers, moneyhungry industrialists, and harried civil servants populated New Caledonia, with 10,000 living in the capital city of Nouméa.

Cigar-shaped New Caledonia is 248 miles long and 31 miles wide. Cocked at a northwest to southeast angle, two steep, razor-backed, rugged mountain ranges run down the length of the island, leaving beautiful secluded valleys and plateaus in between. Most of the island’s towns are built along the coasts with Nouméa on a small peninsula jutting out from the southwest coast about 30 miles from the island’s southern end. Moselle Bay at the very tip of the peninsula was an excellent deepwater port. Situated only 900 miles off the northeast coast of Australia and in almost a direct line between the Hawaiian Islands and Australia, New Caledonia was strategically positioned across the vital seaborne supply and transport lines to and from the United States.

With the fall of France and the establishment of the Vichy government, most of the French colonies in Africa and the Pacific swore to fight on, disregarding instructions from Vichy to lay down their arms. One by one, however, almost all of these colonies came into line and accepted the fact that France had surrendered. To fight on would be treason.

Although the government in the French colony of Indochina initially resisted the capitulation, resistance soon waned as pro-Vichy activists came to the forefront. Japan, an ally of Nazi Germany, was already at war with China and wanted to move into Indochina to cut off outside supplies to the Chinese. In spite of some initial resistance, by September 26, 1940, Japan had moved 40,000 troops into the French colony. To Great Britain, the United States, and especially Australia, the Japanese move into Indochina was a threat that needed to be carefully watched.

In addition to keeping their eyes on Indochina, the three countries began to take a closer look at New Caledonia. On June 24, Governor Georges Pélicier of New Caledonia and the General Council adopted a resolution promising to fight on. As it turned out, however, the governor and council were stronger in word than in deed. As Henri Sautot, a pro-Free French nationalist in the New Hebrides wrote, “That motion seemed more theoretical than practical, for when it came to the point of a decision to rally to General de Gaulle, the fine unanimity of 24 June fell to pieces.”

Throughout July 1940, while Japan solidified itself in Indochina, Australia cozied up to New Caledonia. The world’s leading exporter of nickel, which as an alloy provides strength and quality to many highly stressed metals, the pro-Vichy government in New Caledonia signed an agreement to provide 5,400 tons of high-grade smelted nickel per year to Australia. In return, Australia provided the coal and coke needed to run the blast furnaces. Although Australia was never in need of large quantities of smelted nickel, it monopolized the sale of New Caledonian nickel to support the economy of the French colony.

Because of the Export Control Act that President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed that July prohibiting the “export of essential defense materials,” Japan was no longer getting its refined nickel from America. A Canadian company that bought its nickel from New Caledonia refused to sell to the Japanese in a “moral embargo.” Although New Caledonia would still sell its unrefined nickel to Japan, the Japanese lacked the refineries suitable to smelt it into usable metal.

While nominally still pro-Free French, Governor Pélicier received a telegram from the Vichy government in France instructing him to adhere to a “strict application of [the Vichy] government’s instructions concerning breach of Franco-British diplomatic relations.” In other words, New Caledonia was to have nothing to do with Australia and the British. In reply, Pélicier protested that he needed open trade with Australia in order to avert “famine and grave disorders.” Already Pélicier was hearing rumbling among the people and leading citizens as his government leaned more and more toward Vichy. On July 29, bowing to pressure from France, Pélicier published the new constitutional decrees set down by the Vichy government. Four days later, the General Council passed a resolution proclaiming its disapproval of the governor but did not break ties with Vichy itself, never fully backing the Free French and General de Gaulle.

As the government teetered on collapse, the Japanese sought to gain control of New Caledonia’s nickel. Japanese commissioners in Nouméa lobbied for the precious commodity while Japan put pressure on the Vichy government in France. On August 25, Governor Pélicier received instructions from Vichy “that all production of nickel matte [i.e., refined nickel] and metal ores should be reserved for Japan.” The governor, becoming more pro-Vichy by the moment, passed the instructions on to the head of the New Caledonian smelters. The two men in charge, both pro-Free France, ignored the orders. Additionally, they knew full well that if they switched production to the Japanese Australia would stop shipments of coal and coke and shut down the smelters anyway.

With the publication of the Vichy constitutional decrees, social unrest began to grow. More and more of the populace were leaning toward full cooperation with Charles de Gaulle and the Free French. In response, Governor Pélicier asked Vichy to send a warship to Nouméa. On August 23, the gunboat Dumont d’Urville arrived with a pro-Vichy captain. Although meant to cower the people, the captain reported that the Dumont’s presence only irritated the people more. He also reported that Governor Pélicier was “weak and unequivocal.” On August 28, Vichy instructed the local militia commander, Lt. Col. Maurice Denis, a pro-Vichy activist, to relieve Governor Pélicier of his duties and take over as interim governor. On September 4, the ex-governor boarded a Pan American Airways flying boat and headed for exile in the United States.

While Acting Governor Denis tried to crack down on the Gaullists, General de Gaulle in London received notice that the pro-Free French people of New Caledonia were ready to act. All they needed was a leader. Almost immediately, de Gaulle contacted Henri Sautot in the New Hebrides. If Sautot could go to New Caledonia, he might be able to rally the populace to overthrow the pro-Vichy governor. One of the things that bothered Sautot, however, was the presence of the Dumont d’Urville. Believing that as long as the warship remained in harbor, the pro-Gaullists on New Caledonia would be reluctant to act, de Gaulle requested that the British have an Australian warship accompany Sautot to Nouméa. With the approval of both the British and Australian governments, Sautot set out for Nouméa aboard the Norwegian tanker Norden, accompanied by the Australian cruiser HMAS Adelaide.

Word of Sautot’s arrival preceded him, and on September 19, when Norden and Adelaide reached Nouméa, the New Caledonians marched into the capital and confronted Governor Denis, demanding that he either come over to the side of the Free French or resign. By 3 pm, backed by a wild and enthusiastic crowd, Henri Sautot succeeded Colonel Denis as governor of New Caledonia. Almost a week later, after obtaining assurances that none of the pro-Vichy officials and activists would be arrested or harmed, Dumont d’Urville left Nouméa and sailed to Indochina.

Starting with almost nothing, Governor Sautot began to piece together a working government, relying on economic aid from Australia to help stabilize the situation. In Australia, officials began to fear that the Japanese might take advantage of the destabilized condition of the colony to try a takeover. With most of its warships in the Mediterranean supporting Britain against Germany, Australia did not want a Japanese presence only 900 miles off its eastern coast.

Over the next two months, Australian and New Caledonian authorities agreed to turn New Caledonia into an advance base that would include both flying boat and land-based aircraft facilities, two six-inch coast guns and searchlights at Nouméa, and arms and equipment for a local defense force. While all of these activities benefitted the New Caledonians, the Australians also saw this military buildup as protection for their own country, concluding that the protection of New Caledonia would contribute materially to the defense of Australia in the event of war with Japan. By mid-May 1941, after obtaining approval from General de Gaulle, work was completed on the initial military buildup around Nouméa. Over the next few months, additional airstrips were built at Tontouta, about 34 miles north of the capital along the west coast, at Plaine des Gaiacs on the west coast, and at Koumac near the northern tip of the island.

With the war in Europe and rising fears of eventual war with Japan, the economic outlook in New Caledonia began to improve. As the United States became the great “Arsenal of Democracy,” American factories began turning out weapons for Great Britain and her allies. Simultaneously, the need for New Caledonian nickel matte and chrome increased dramatically. As the demand for nickel went up, so too did the economy of New Caledonia. Unfortunately, as the importance of New Caledonia’s raw materials and strategic geographic location increased, so too did de Gaulle’s worries of British, Australian, and American motives toward the Free French colony.

On April 18, Governor Sautot had sent a telegram to de Gaulle complaining that the Australian government was imposing “unacceptable” controls on the island’s economy. Officials in New Caledonia believed that “Australia merely desires to exploit New Caledonia in Australian interests.”

In a memorandum, the Free French in London complained that New Caledonia’s economic interests had been sacrificed to those of the British Empire. Having had many bitter disputes with his British hosts, de Gaulle was suspicious of Allied intentions toward New Caledonia and the other French possessions in the area. Wishing to have a loyal, trusted representative in the area, General de Gaulle named his friend Captain Georges Thierry d’Argenlieu High Commissioner for France in the Pacific and dispatched him to Nouméa.

Although d’Argenlieu has been described as vain, meticulous, devious, ambitious, and filled with “lofty pride,” de Gaulle trusted him completely. He was instructed to go to New Caledonia and sort out the defensive arrangements made with Australia. The newly promoted Rear Admiral d’Argenlieu arrived in Nouméa on November 6 and immediately began to familiarize himself with the situation. Shortly thereafter, two U.S. military officials, one from the Air Corps and one from the Corps of Engineers, arrived apparently unannounced.

Unknown to either d’Argenlieu or de Gaulle, on October 15 the United States had requested permission from the British, Australian, and New Zealand governments and the Netherlands government in exile in London to help in the construction of airfields throughout the Pacific. Unfortunately, the United States had not spoken to General de Gaulle or the Free French. Although d’Argenlieu allowed the officials to complete their survey of the airbases already established by the Australians, he showed deep resentment that he, de Gaulle, and the Free French had not been privy to their arrival.

On November 21, de Gaulle sent d’Argenlieu specific instructions on setting up rigid safeguards of French sovereignty and authority and specifying that all airdromes built on French soil would be under exclusive French control. When the two American military officials suggested that the airstrip at Plaine des Gaiacs be expanded to accommodate heavy bombers, d’Argenlieu halted construction completely until he received word from the Free French delegation in Washington, which was working out an agreement with the U.S. State Department.

Perhaps still unable or unwilling to accept the complicated political situation on New Caledonia, the United States War Plans Division wrote to the State Department on December 4, explaining that the Army Air Corps desired to expand the runways at Plaine des Gaiacs and had “contracted with the Australian Government to improve the field.” The report continued, “The Army desires the Australian Government to assume responsibility for defense.” Nowhere in the report did the War Plans Division mention the Free French or indicate that it was actually the Free French that controlled the island of New Caledonia.

All arguments ended on December 7, 1941, when the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor. The next day, General de Gaulle telegraphed d’Argenlieu to place “at the disposal of the Allied Forces all the facilities that may be offered by bases in the New Hebrides, Tahiti and New Caledonia.” He added, “As soon as a state of war exists between Great Britain and Japan you will consider yourself at war with the latter.” Britain, of course, declared war on Japan that same day, and though d’Argenlieu allowed the work on the airfield at Plaine des Gaiacs to proceed he was fearful that the expanded airdrome would make the island even more desirable to the Japanese.

For defense New Caledonia boasted an 800-man French garrison, two light coastal defense batteries, and a poorly armed colonial French home guard. Although Australia had no excess military personnel to send to New Caledonia since most of its forces were fighting the Germans and Italians in North Africa, a 300-man commando unit was quickly rushed to New Caledonia to enhance the morale of the Free French Forces.

On December 10, 1941, an officer with the U.S. State Department wrote, “I believe we ought to call to somebody’s attention to the fact that according to our latest information Australia has not taken over [New Caledonia’s] defense. The loss of New Caledonia to the Japanese would, of course, constitute a considerable blow to our whole war effort.”

When Chief of Staff General George C. Marshall asked his Deputy Chief of the War Plans Division, Brig. Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower, to draw up a plan for what action should be taken in the Pacific, Eisenhower concluded that the Philippines were untenable and that the only place to start operations against the Japanese was Australia. Concluded Eisenhower, “Our base must be Australia, and we must start at once to expand it and to secure our communications to it.” Of course, the communications to Australia led through Hawaii, Fiji, New Caledonia, and New Zealand.

Unknown to anyone in Washington, however, the real threat to New Caledonia was not the Japanese. After December 7, when Japanese troops were running rampant throughout the area, Vichy officials envisioned a decisive Japanese takeover of the southern Pacific. In a communiqué to the Japanese embassy at Vichy, Marshal Pétain’s government expressed that if the Japanese continued to push southward, “French aircraft and a detachment of French troops [from Indochina] could take part in the event of actions against New Caledonia.”

The Vichy French would take back New Caledonia and offer Japan the much needed supply of smelted nickel.

In mid-January, plans were being made for French warships in Indochina to race to New Caledonia ahead of the Japanese and retake the island in the name of the Vichy government. This expedition would establish the “permanent sovereignty” of New Caledonia as a pro-Vichy colony. On January 23, a telegram was sent to Vichy outlining the plan and asking for the approval of its undertaking as soon as the Japanese zone of action came sufficiently close to New Caledonia. Fortunately for the Allies, events happening elsewhere prevented the Vichy French in Indochina from making their move south.

While the Indochina Vichy were waiting for a reply, a hastily assembled American task force was steaming toward New Caledonia. On January 23, 1942, a conglomerate force of hastily assembled units totaling 17,000 soldiers and service personnel left New York City for Melbourne, Australia, where they would be shipped to New Caledonia. The task force commander, Brig. Gen. Alexander M. Patch, Jr., would fly to Australia and meet his new command at Melbourne.

While the ships were en route, officials in Washington began hearing rumors of the intended Vichy move toward New Caledonia. Immediately, Washington warned the Vichy government against any change in the status quo in her Pacific colonies. What was Vichy would stay Vichy, what was Free French would stay Free French. On February 22, before the American reinforcements had arrived, the State Department sent a message to Nouméa announcing, “This Government recognizes, in particular, that French island possessions in that area are under the effective control of the French Nationalist Committee [i.e., General de Gaulle]…. [The United States] Government appreciates the importance of New Caledonia in the defense of the Pacific Area.”

At the same time, High Commissioner d’Argenlieu was having a fit. Never informed that an American task force was on the way, d’Argenlieu was angered that the Americans were unwilling to commit troops and matériel to New Caledonia. In late January, he sent a telegram to de Gaulle outlining his frustrations. “From the United States we have obtained only the appointment of a liaison officer. No reply to our urgent request for equipment…. The United States seems determined to extract from us all they need without any compensation.”

Always suspicious of the underlying intentions of both the United States and Australia, d’Argenlieu added, “I apprehend, without any firm confirmation, a secret combination between America and Australia to impose on us, without prior consultation, the landing of American troops. You have instructed me not to accept such a thing. I shall carry out my orders by every means.”

Worried that d’Argenlieu would resist the arrival of American troops, the U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff sent a communiqué to de Gaulle informing him that the British and the Americans “appreciated the importance of New Caledonia and have initiated measures for its defense.” Nothing was stipulated, but the general was assured that help was on the way. The telegram concluded, “It is requested that you so inform the High Commissioner at Nouméa, and impress on him the necessity for absolute secrecy.”

When d’Argenlieu received the information on February 1, with no details, he still felt snubbed. In the future, he insisted on being informed well in advance of any proposed American support. He also insisted that any American force landing in New Caledonia was to be placed under his command. Hoping to placate the high commissioner, General Marshall instructed General Patch to meet with d’Argenlieu. The two men met on March 9 at Nouméa, and three days later d’Argenlieu reported to de Gaulle, “Contact is now established between Patch and myself … it seems clear that the command of the Allied forces in New Caledonia can be held only by Patch, whose forces and resources are overwhelming in comparison to ours. Having requested him to communicate his instructions to me … [he] assured me that he would keep me informed of all his activities.”

On February 26, the American task force arrived at Melbourne. American troops landed at Nouméa on March 13. By the end of the month, another 5,000 American troops from a heavy artillery regiment arrived, giving General Patch more than 22,000 troops. Later, the 164th Infantry Regiment arrived to further increase the American presence.

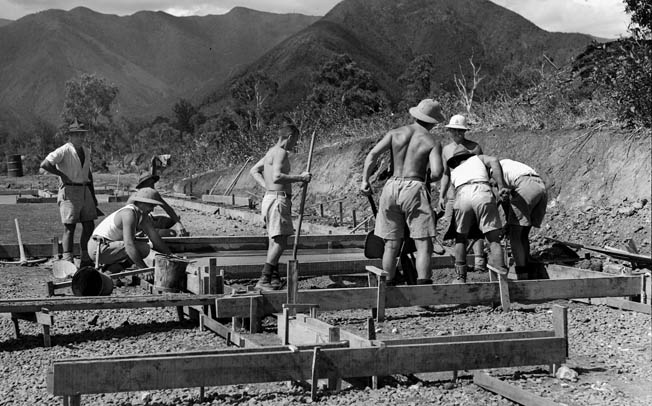

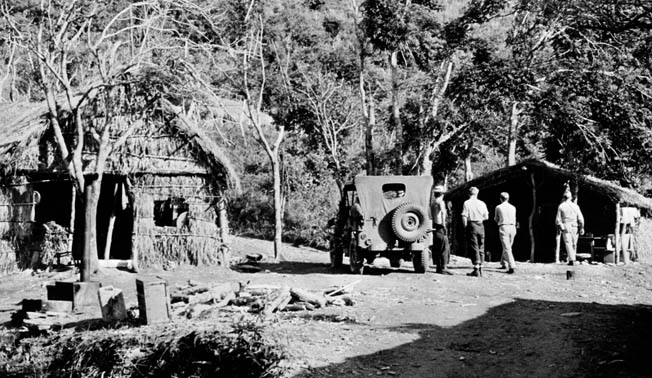

New Caledonia was not prepared for the sudden influx of Americans; nor were the Americans ready for New Caledonia. There were no facilities to house or shelter the troops, and the Americans had no information on where to go or how to get there. Fortunately, General Patch soon acquired the services of three Australian liaison officers. In time, the Army engineer and supply troops managed to get a hold on the situation, and with the assistance of the Australian liaison officers began sending supplies and equipment, including crated airplanes and parts, along the “little Burma road” that connected the port of Nouméa with the unfinished Australian airfields and some new defensive positions established around the northern tip of the island.

Near the end of March, General Douglas MacArthur, who had left the Philippines and relocated to Australia, was made Supreme Commander of the Southwest Pacific Area, which extended east of Australia to the 160th meridian with a slight bulge incorporating the Solomon Islands. The rest of the Pacific was placed under the command of Admiral Chester Nimitz as Commander-in-Chief Pacific. The separate sea areas of New Zealand, the New Hebrides, Fiji, Samoa, and New Caledonia were placed under the South Pacific Area. On April 19, Vice Admiral Robert L. Ghormley was placed in command of this area with his headquarters at Auckland, New Zealand. Ghormley was told that soon, perhaps by autumn, he would have enough troops and equipment to go on the offensive.

It took months for General Patch to meld his motley crew into a well-trained fighting machine. In May 1942, he was unwillingly dragged into the political mess that was New Caledonia. Although Admiral d’Argenlieu was the high commissioner for France in the Pacific and responsible for all of the French island colonies in the area, he continued to reside at Nouméa and make decisions that should have been made by Governor Sautot. When some of the locals began to complain, d’Argenlieu convinced General de Gaulle that he alone could deal with the turbulent conditions in New Caledonia and got the general to “invite” Governor Sautot to London to receive a new assignment.

Although Sautot originally agreed, he eventually changed his mind after deciding that d’Argenlieu just wanted him out of the way. On May 5, after Sautot sent a message to de Gaulle requesting to remain as governor, troops loyal to d’Argenlieu rounded up Sautot and four of his leading supporters and spirited them out to the waiting sloop Chevreuil.

One of Sautot’s confidants, George Dubois, managed to avoid being arrested and rushed to General Patch seeking American assistance. Unwilling to interfere in island politics, especially when he was trying to put together a viable fighting force, Patch sent Dubois home but provided him with an armed escort. It was this single act that aroused anger on both sides. New Caledonians loyal to d’Argenlieu argued that Patch should have arrested Dubois, while those loyal to Sautot complained that Patch should have freed the governor and the others who had been falsely arrested.

The next morning, Chevreuil, carrying Sautot and his four compatriots, started out for New Zealand. On the way, Chevreuil heard distress calls from a Greek ship that had been torpedoed by a Japanese submarine. Although the Greek ship was only 30 miles to the south and Chevreuil was equipped with the latest anti-submarine devices, the captain ignored the call and continued on, so intent was the anti-Sautot faction to get rid of the governor. Then, after dropping off the four leaders at the tiny island of Walpole about 150 miles from Nouméa, the ship went on to Auckland, where Sautot was put ashore. Accompanying Sautot was a liaison officer who was to keep tabs on him until he was safely in England.

The next day, Patch complained to d’Argenlieu that Chevreuil had ignored a distress call and did not participate in the search for the Japanese submarine. Patch told the admiral that three American ships carrying troops and supplies were close to New Caledonia and within the danger zone of the Japanese sub. He requested that d’Argenlieu return Chevreuil to help in the search. In response, the admiral stated that he would be willing to recall the sloop “for a few hours” but only if Patch told him specific details about the routes and contents of the three American ships. This Patch was unwilling to do, so Chevreuil stayed in Auckland and relations between the Americans and the Free French worsened.

When the people of New Caledonia discovered that Chevreuil had taken away their leaders, they rose up. To help quell the disorder, d’Argenlieu asked Patch to use American troops to disperse the mob. Patch refused. In a dispatch to Washington, Patch explained the situation and said that he expected the trouble to escalate unless d’Argenlieu were removed. Patch went on to write that if the Americans helped d’Argenlieu the United States would “lose the military support of the local militia and the entire population [which backed Governor Sautot].” He then asked if he had the military authority to place d’Argenlieu and his staff under protective arrest since “the disorders grew into an immediate and dangerous military threat.”

British authorities were shocked by what was happening in New Caledonia. As author John Lawrey wrote, “D’Argenlieu’s behavior … seemed incredible. New Caledonia was on the very edge of the battle and might be an early objective for the enemy. But at this very moment [d’Argenlieu] had chosen to dismiss the Governor who had brought the island over to de Gaulle and had worked in harmony with both the British and the Americans.” The British put pressure on de Gaulle to straighten things out on New Caledonia.

On May 8, d’Argenlieu conveniently left Nouméa for a visit along the west coast in order to rally the population, which had been disgracefully misled by foreign-concocted propaganda. Once away from the capital city, however, he was arrested by local authorities. Wishing to avoid any unpleasantness, General Patch pressured the locals, without using the American military, and had d’Argenlieu released. Eventually, the locals managed to get d’Argenlieu to agree to the return of the four leaders that had been dropped off at Walpole Island. On May 17, the men returned to a cheering crowd.

In London, de Gaulle repeated d’Argenlieu’s claim that the United States was nothing more than “a democratic country with imperialistic ambitions” hoping to kick the French out of New Caledonia at a time when France was weak and take over the island for itself. Over the next few months, de Gaulle repeatedly spoke of “American imperialism” and instructed his followers to resist any American attempt to control any of the island colonies in the Pacific. Accordingly, Commissioner d’Argenlieu wrote, “We have only one objective in Nouméa, which is to see that the island remains French while at the same time assuring its defense.”

In early May, however, General de Gaulle, Admiral d’Argenlieu, and all of New Caledonia found out just how desperately they needed to work with the Americans to defend their island. On May 3, Japanese forces captured Tulagi in the Solomon Islands, and on May 10 it was reported that a Japanese aircraft carrier was headed toward New Caledonia. General Patch’s command and the island militia were put on full alert. As it turned out, the Japanese ship was part of the invasion force headed toward Port Moresby, New Guinea, that eventually turned back after the Battle of the Coral Sea. Although the immediate threat was over, it had emphasized how much the different factions needed to work together for the common good of New Caledonia.

In an attempt to mollify d’Argenlieu, Patch sent the high commissioner an apology for involving himself in the Dubois affair. He did, however, request that no further action be taken against Dubois. To the Free French, Patch’s apology was an admission of guilt for taking sides in local politics. Both d’Argenlieu and de Gaulle highly resented the “American interference.” Admiral d’Argenlieu harbored a deep hatred for General Patch and the Americans, and when Vice Admiral Ghormley passed through Nouméa on his way to Auckland on May 20, d’Argenlieu handed him a long list of unsubstantiated complaints against Patch.

Virtually until American troops landed at Guadalcanal in the Solomon Islands on August 7, 1942, the high commissioner kept a running correspondence of petty grievances with Patch. At the same time he repeatedly reminded Patch that he was not under any authority other than de Gaulle in London. Unfortunately, the British invasion of Vichy-controlled Madagascar off the eastern coast of Africa only added to de Gaulle’s and d’Argenlieu’s suspicions that the British and Americans were out to take over all pre-World War II French colonies.

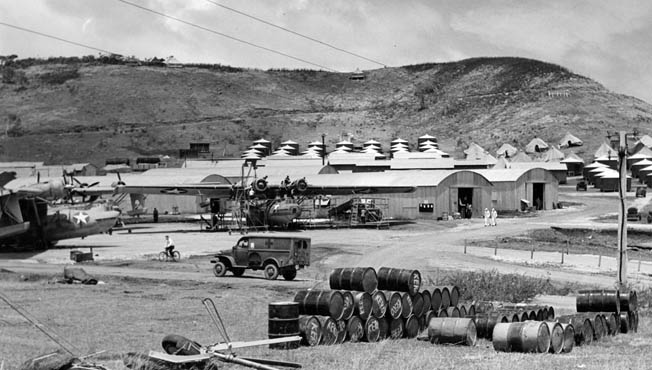

On May 23, the conglomerate American military force on New Caledonia was officially organized into the 23rd Infantry Division, better known as the Americal Division from “Americans on New Caledonia.” Until November 1942, the Americal Division and the handful of Australian and local troops would be the only defenders on New Caledonia. Eventually, as the island became a major supply base for the Solomons campaign, more American troops were brought over, peaking at 50,000.

Between June 29 and July 2, 1942, the American Joint Chiefs of Staff devised a plan to take back Tulagi in the Solomons. Then, when it was discovered that the Japanese were building an airstrip on nearby Guadalcanal, the decision was made for the newly formed 1st Marine Division to invade the two islands as soon as possible. To place the invasion under Navy control, the Joint Chiefs shifted the boundary of MacArthur’s Southwest Pacific Area to the west and placed the Solomon Islands in Admiral Nimitz’s command and within Admiral Ghormley’s South Pacific Area.

A cautious, worrisome individual, Ghormley did not want to move against the Solomons. He felt that his forces were not ready. In a letter written in conjunction with General MacArthur, who also felt that the United States was not ready to take the offensive, the two men wrote, “[We] two commanders are of the opinion, arrived at independently … that the initiation of the operation at this time … would be attended with the gravest risk. It is recommended that this operation be deferred.” The Joint Chiefs ignored the recommendation. The invasion would go on. Unfortunately, Ghormley remained pessimistic throughout the campaign.

T

o prepare for the August 7 invasion date, Ghormley moved his headquarters from Auckland to Nouméa, 1,100 miles closer to the Solomons. Although described as a pleasant man, it has been written that Ghormley was nearing the end of his career and was already mentally and physically tired. He was no match for either High Commissioner d’Argenlieu or the new governor, Auguste-Henri Montchamp, who was seen as a carbon copy of d’Argenlieu. When Ghormley arrived at Nouméa aboard his aging headquarters ship USS Argonne,he was informed that he and his staff could not come ashore and that he could not use any offices in town. Nothing was available. Never one to ruffle feathers, Ghormley did not push the issue but calmly settled into his office on the sweltering Argonne,which had never been upgraded for air conditioning, and began to direct the campaign against Guadalcanal from there.

Governor Montchamp did not trust the Americans and felt that they were “rude and aggressive.” Another crony of Charles de Gaulle, Montchamp helped take some of the pressure off d’Argenlieu in dealing with the Americans. Whenever Admiral Ghormley got up the nerve to ask for office space on New Caledonia, Montchamp flatly refused. In his appointment by de Gaulle as the new governor of New Caledonia, the Free French leader had stressed the need for someone that would work well with d’Argenlieu and would stand up to the Americans in spite of their immense resources. He got just that in Governor Montchamp.

On August 7, the Americans stormed ashore on both Tulagi and Guadalcanal. Although the land operations went well, the American navy suffered one of the worst defeats in United States naval history on August 9 after Admiral Ghormley allowed an old Naval Academy friend, Vice Admiral Frank J. Fletcher, to pull his three aircraft carriers and their supporting ships far away from the Solomons after only 36 hours on station. In the night Battle of Savo Island, the Americans lost three cruisers along with one Australian Navy cruiser and had one cruiser and one destroyer damaged. The Japanese had only one destroyer damaged. In his official report to Nimitz, Ghormley covered for Fletcher’s early withdrawal by reporting simply, “Carriers short of fuel proceeding to fueling rendezvous.”

Over the next few weeks, Admiral Fletcher and his carriers stayed far south of Guadalcanal, purportedly protecting the sea lanes between the Solomons and Australia while the Japanese poured thousands of men onto Guadalcanal. During daylight hours, Japanese air raids came at will, and at night Japanese ships bombarded the captured airstrip and U.S. Marine positions on the island.

Although Fletcher’s carrier planes could have provided much needed help, neither he nor Ghormley responded. Finally, on August 24, Fletcher moved his carriers forward and engaged the Japanese in the Battle of the Eastern Solomons. In the ensuing fight the Americans sank one Japanese carrier, one destroyer, and one light cruiser, while the Americans suffered one carrier damaged. A few days later, however, Japanese submarines sank a second American carrier and damaged a third. With all his carriers either lost or damaged, Fletcher seemingly lost confidence and requested immediate sick leave. It was granted. He never returned.

Ghormley contacted MacArthur for his thoughts, and once again the two commanders jointly told Nimitz that Guadalcanal could not be held. The Marines would have to be pulled out. This defeatist attitude angered Nimitz. He knew that the Japanese were fully committed to holding Guadalcanal. They had lost thousands of men, dozens of ships, and hundreds of planes defending the island. Although the Marines were barely hanging on, Nimitz argued that they were doing just that—hanging on. And America was just beginning to rise up to its full potential. The situation on Guadalcanal was going to get better!

Vowing to see for himself what was happening in the South Pacific, Nimitz flew to Nouméa for a meeting with Ghormley. Amazingly, Nimitz found his old Naval Academy friend sitting aboard his sweltering headquarters ship, unwilling to provoke the Free French authorities ashore. Although Nimitz had told Ghormley to “exercise strategic command in person,” he discovered that in almost two months’ time Ghormley had never visited Guadalcanal.

After visiting Guadalcanal, where Nimitz discovered that the Marines themselves were highly optimistic about their chances of defeating the Japanese, he returned to Nouméa for another meeting with Ghormley. Nimitz wanted to know why South Pacific warships were not being used to stop the Japanese from reinforcing Guadalcanal. He wanted to know why the Americal Division, training on New Caledonia since March, had not been sent to reinforce the Marines. He wanted to know why other islands had not been stripped of their garrisons to reinforce Guadalcanal.

After Nimitz left, Ghormley dispatched the 164th Infantry Regiment of the Americal Division to Guadalcanal. While protecting the convoy of transports, a screening force of American warships surprised a smaller Japanese naval force just north of Guadalcanal on the night of October 11-12. In the Battle of Cape Esperance, the first night victory for the U.S. Navy, the Americans sank one cruiser and one destroyer and damaged two more cruisers. The Americans lost only one destroyer but had two cruisers and two destroyers damaged. On October 13, the first of the Americal Division troops went ashore unmolested.

When Nimitz returned to his headquarters in Hawaii, he immediately began stripping the Central Pacific bases of planes and forwarding them to Guadalcanal. At the same time he notified the Army’s 25th Division in Hawaii to be ready to move forward at a moment’s notice. He also realized Ghormley was on the verge of a nervous breakdown so he sent Admiral William F. “Bull” Halsey to Nouméa for a further study of the South Pacific area. After Halsey’s seaplane touched down in Nouméa harbor on October 18, he opened a sealed envelope that had suddenly been handed him. “Immediately upon your arrival at Nouméa,” the dispatch from Nimitz read, “you will relieve Vice Admiral Robert L. Ghormley of the duties of Commander South Pacific and South Pacific Force.”

Halsey responded, “Jesus Christ and General Jackson! This is the hottest potato they ever handed me!”

While Patch and Ghormley had been easy-going and almost apologetic to the Free French authorities on New Caledonia, Halsey was aggressive and impatient. When Halsey introduced himself to Governor Montchamp, since High Commissioner d’Argenlieu had removed his headquarters to the Free-French controlled island of Tahiti, he found Montchamp to have an undeserved “aloof attitude.” Wrote Halsey, “The French governor kept sulkily (but not silently) aloof in his ‘palace’ on the hilltop.”

To help negotiations between the Americans and the Free French authorities on New Caledonia, Washington asked de Gaulle to allow Governor Montchamp to deal directly with Halsey without going through London. Although de Gaulle agreed, Montchamp continued to insist that he had to check with London first before making any crucial decisions, thus delaying everything indefinitely. Although far away on Tahiti, Commissioner d’Argenlieu supported everything that Montchamp did.

In the first six weeks between October 18 and December 1, Halsey’s new command fought three naval battles and several land battles. In each naval engagement, Japanese forces were turned back from their missions of shelling the Marines on Guadalcanal or reinforcing their own troops. In the ground action, the reinforced Marines stopped each enemy advance and managed to expand their defensive perimeter around Henderson Field, the vital base for American aircraft operating from Guadalcanal.

The importance of Nouméa’s harbor came to the forefront after the October 25-27 Battle of Santa Cruz Islands, when the damaged aircraft carrier Enterprise limped into the harbor for immediate repairs instead of retiring all the way to Pearl Harbor. By November 11, she was back in action off Guadalcanal.

In December, during a lull in the fighting, Halsey, still aboard Argonne, wrote, “I was able to turn my attention, for the first time, to organizing my command and settling in for the long struggle ahead.” Delegating authority, Halsey began to expand his staff. “Operations alone was getting the full-time attention of twenty-five of my officers,” he wrote.

Knowing full well that remaining on the overcrowded, stifling Argonne was not going to work, Halsey sought better working and living conditions. “I have always insisted on comfortable offices and quarters for my staff,” he wrote. “Their day’s work is so long, their schedule so irregular, the strain so intense, that I am determined for them to work and rest in whatever ease is available.”

Although knowing that Admiral Ghormley’s repeated requests to move his offices ashore had constantly been refused by the Free French, Admiral Halsey figured he would try again.

Realizing the importance that the French officials attached to decorations, Halsey instructed Lt. Col. Julian P. Brown, one of his staff members, to put on his dress uniform adorned with all his medals, including a Croix de Guerre awarded during World War I, and see Governor Montchamp to ask for accommodations on shore. “What do we get in return?” Montchamp asked. “We will continue to protect you as we have always done,” Brown replied. Montchamp said he would see what he could do.

Instead, the governor sent off a blistering note to de Gaulle. He informed the general, “The imperious and constantly increasing requests of the Allied commanders … are making the situation impossible.” He told the Free French leader that U.S. Army officers were occupying every available space. If the U.S. Navy wanted to come ashore, the Army personnel would have to move out. There was not room enough for both of them. In Tahiti, Commissioner d’Argenlieu backed Montchamp fully. He informed de Gaulle that the Americans were already occupying every newly constructed building, laying the blame upon the old governor. “Sautot always gave in to their requests.”

Two more times in December, Halsey requested permission to move his staff ashore. Each time Governor Montchamp either refused outright or told Halsey that he would have to contact London to see what they had to say. Halsey knew that it was nothing but a stall tactic. Finally, when Colonel Brown met with Montchamp a fourth time he told the governor straight out, “We’ve got a war on our hands and we can’t continue to devote valuable time to these petty concerns. I venture to remind Your Excellency that if we Americans had not arrived here, the Japanese would have.” Unperturbed, Montchamp just shrugged his shoulders.

When Halsey heard about Montchamp’s response, he remembered, “We simply moved ashore.” Finally fed up with the haughtiness of the Free French governor, the short-tempered Halsey called for his barge and loaded on an impressive Marine Corps guard. Recalled Halsey, “The offices ‘put at our disposal’ had been the headquarters of the High Commissioner for Free France in the Pacific.”

Knowing that the high commissioner’s offices were unoccupied since d’Argenlieu was in London, Halsey and his Marine escort came ashore and marched up to the offices. While some of the Marines surrounded the building, a few others raised the Stars and Stripes from the flagpole. Halsey was there to stay.

“We were still crowded in our new offices, but not so badly as on the Argonne,” Halsey wrote. Next, Halsey and his Marines went in search of living quarters. For Halsey they seized a brick house on a “cool, airy hilltop” that had belonged to the Japanese consulate. Earlier in the war, the consul himself had been sent to Australia for internment.

“The chairs were so squatty that we felt as if we were sitting on the deck, and the tables hardly reached our knees,” Halsey wrote. “My Filipino mess attendants never became accustomed to my response when they broke a piece of the consul’s china. Instead of bawling them out, I told them, ‘The hell with it! It’s Japanese.” Halsey’s deepest satisfaction, however, came every morning when his Marine guards “raised the American flag over this bit of property which had once belonged to a representative of Japan.”

Once ensconced in the consulate building, Halsey looked for living quarters for his staff. “[We] eventually established ourselves in a cluster of buildings constituting a miniature International Settlement,” Halsey explained, “two Quonset huts, which we christened ‘Wicky-Wacky Lodge’; [and] one ramshackle French house, ‘Havoc Hall.’” Needing more, he pressed the governor for additional living and working space. Montchamp, already angered by Halsey’s uninvited foray into town, again refused. “It appears to be just an entire lack of desire to cooperate,” Halsey reasoned.

To his own superiors, Montchamp wrote that the Americans were “trying to kill French life, by suppressing little by little through requests based on military considerations, all our organization—to substitute for it some American form which would lead to the ruin of all that is French.”

Halsey did not care about the French way of life. He had a job to do and would get it done no matter whose feathers he ruffled. “Our principle difficulty,” he noted, “lies in the non-cooperative ‘business as usual’ attitude of the French. They are jealous of their prerogatives and anxious to preserve, war or no war, French traditions and customs.” He summed up the situation by adding, “I think they desire to avoid the mental discomfort of changing their habits and the physical discomfort of contracting their installations to make room for us.” In spite of the war, Halsey felt that the Free French want “life as usual.” He concluded they were “more obstacles than allies in the war effort.”

On January 4, 1943, while Free French and American relations on New Caledonia remained tense, the Japanese finally decided to abandon Guadalcanal. Although Halsey had anticipated moving his headquarters out of Nouméa as soon as possible, he quickly learned that it was not to be. New Caledonia had become the main staging area for American troops and supplies flowing into the Solomons. By May 1943, realizing he would be staying longer than expected, Halsey asked for more facilities. In response, Commissioner d’Argenlieu sent Halsey a list of all of the buildings and facilities that the Americans were already occupying and insisted that the Free French forces could not give up any more buildings. D’Argenlieu wanted to know why the Americans did not build their own buildings as they had done in Australia.

When Halsey read the commissioner’s reply, he ordered his staff to put together a list of all of the buildings that had been constructed by the Americans and all of the improvements they had made to Nouméa. When finished, the list showed that the Americans had built 2,186 structures on New Caledonia, including 271 warehouses. The report also showed that for every 1,000 U.S. troops on New Caledonia, 905 were living in tents, 90 were living in American-built buildings, and the other five were in French houses, mostly officers paying rent to the French owners. Halsey sent his list and an accompanying report to London to “entirely refute the impression Admiral d’Argenlieu gave of us.”

As the American juggernaut continued up the Solomon Islands chain, New Caledonia took on more and more importance. In 1943, Nouméa was second only to San Francisco in the amount of tonnage passing through a Pacific port. In November 1942, when Admiral Halsey took over, Nouméa was handling 1,500 tons a day. By early 1943, with improved management and an increase in storage space in Quonset huts built near the docks, the port was handling more than 10,000 tons a day. Unfortunately, this increase in activity meant further inconveniences for the New Caledonians since military goods had priority in unloading and civilian items sometimes had to wait days to be brought ashore.

The unforeseen hardships for the New Caledonians seemed to overwhelm Governor Montchamp and the authorities. As goods sat on the ships waiting to be unloaded, prices began to rise. As one American put it, price control was “only a phrase.” Inflation increased, and rationing was poorly controlled. Fresh meat, fruit, and vegetables were in short supply. The town and peninsula of Nouméa were totally swamped by this unprecedented military occupation.

While many townspeople came to resent the sprawling occupation of the Americans, as the population of Nouméa tripled others found the occupation an economic boom. Laborers found jobs on the docks and in the warehouses, women worked as laundresses, and many women and children sold sandwiches and soft drinks. Unfortunately, many of the snacks and drinks came from American canteens and snack bars, which paid no local taxes and higher wages than the local establishments. French businesses suffered from this unfair competition.

As American tent cities sprang up all over New Caledonia, the two cultures clashed. It was reported that many New Caledonians were angry because “their cattle had been killed, their fences torn down, roads built over their property, trees cut down and many other things done.” An American report confirmed, “The feeling is increasing, and unless the destruction and stealing by the U.S. forces here is curbed there may be difficulty.” This time, instead of complaints coming from Montchamp or d’Argenlieu, or even de Gaulle, the complaints were coming from the people themselves.

New Caledonians began to believe the talk that the Americans wanted to take over the island. Australian officials on New Caledonia received an anonymous report on the anti-American feelings. “There are many insular and bone-headed [Americans], possibly even more among the officers than enlisted men,” stated the report, “who think nothing of insulting the French openly, and of discussing in public whether or not America will have the bounty to take over New Caledonia now, or after the war.”

Fearing an outright rebellion, General Rush Lincoln, in charge of the First Island Command, a collection of American units with the sole duty of protecting New Caledonia, tried to calm the islanders’ fears. In a radio speech given in March 1943, the one year anniversary of the arrival of the American troops, Lincoln assured the people that the Americans were only there to protect New Caledonia, not to take over their country. He regretted the inconveniences placed upon the New Caledonian people but said that it was necessary during a time of war. He finished by thanking the people for their hospitality and understanding. The speech was then broadcast in French and later published in both English and French. Although allaying some fears, followup reports indicated that there was a “cooling” of friendliness toward the occupying Americans.

By June 1943, Governor Montchamp had had enough. After 10 months in office he had come to despise the Americans, the New Caledonians, and the politics of the island. Writing to High Commissioner d’Argenlieu, Montchamp asked to be reassigned. “I most ardently hope, Admiral” he wrote, “to never return here and wish to be assigned to a combat unit.” He termed New Caledonia a “graveyard for governors.” Having fallen into disfavor with d’Argenlieu because of his inability to stand up to Halsey and the Americans, the high commissioner was more than happy to let him go.

On August 28, an interim governor arrived in Nouméa. He was Christian Laigret, d’Argenlieu’s handpicked man and another rabid Gaullist. Laigret continued with the long list of complaints against the Americans; however, this time he had the backing of the people. One of his first acts was to take a tour of New Caledonia to speak with the people and see firsthand the destruction caused by the Americans. He was shown the downed fences and telephone lines, the cattle killed by soldiers hunting deer, and the damage done to fields and roads by American vehicles. The interim governor agreed to make amends and pursue complaints against the Americans.

One of Laigret’s biggest complaints concerned the actions of American soldiers and sailors toward the women of New Caledonia, especially African American soldiers, who had begun arriving in New Caledonia in late 1942. Laigret complained that the attitude of the black soldiers toward the New Caledonians was aggressive and offensive and that the African Americans prowled the streets looking “for adventures.” While the governor wanted blacks banned from the city of Nouméa completely, General Lincoln refused. Instead, the general settled on restricting the African Americans to visiting only certain parts of the city, perhaps unwittingly reinforcing America’s policy of segregation. Additionally, the American military police and shore patrol presence was increased.

Governor Laigret also complained about the impact that the influx of American dollars was having on New Caledonia’s economy. While some islanders were reaping great benefits from working with or for the Americans, others were suffering. Civilians were finding it hard to purchase such necessities as sugar and flour, while great quantities were being sold to the Americans. The ability of United States authorities to outbid the local businessmen meant that American vehicles had all the oil and gasoline they wanted and American servicemen had all the food and drink they desired.

American authorities were also accused of hiring native workers, called Kanak, over New Caledonians. Governor Laigret and many of the Free French felt that this was elevating the dark-skinned Kanaks over the light-skinned New Caledonians and giving the natives an unprecedented new status on the island. Laigret felt that this elevated status would make it hard for the French to control the Kanak after the Americans departed.

To try to control activities within his own government, Laigret began to dismiss French officers that he felt had become too friendly with the Americans. Although he continued to act on orders from Free French authorities who wanted to ensure the maintenance of French sovereignty in New Caledonia, Laigret became a liability. His strong anti-American stance and his inability to work with both the Americans and some of the highest members of New Caledonian society eventually led to his recall in December 1943. However, before he left he gave two blistering speeches on what he thought of the Americans and how New Caledonia would go to ruin without him.

Halsey was glad to see Laigret go and wrote, “Governor Laigret has failed utterly to appreciate the necessity for cooperation in the war effort, has deliberately attempted to sow the seeds of dissension between French residents … and the American forces…, has utilized the powers of his office to intimidate those who have been friendly toward the Americans, and has thus prevented the friendly cooperation that should prevail.”

Halsey concluded, “Under no circumstances should New Caledonia be handed back to the French; its administration is a disgrace.” What Halsey failed to understand, however, was that the United States was not in control of the island and had nothing to hand back. Although at one point President Roosevelt actually questioned whether the French should remain in control of New Caledonia once the war was over, the United States never made a firm attempt to keep the Free French from controlling the island once peace was restored.

In February 1944, a new governor, the sixth since the fall of France in 1940, took over and immediately began to repair the relationship between the Free French and the Americans. Although Jacques Tallec was pro-Gaullist, he was determined to work with the United States to ensure the protection and prosperity of New Caledonia. Unlike the previous governors, Tallec felt confident that although the Americans might want to keep a military base on New Caledonia after the war they had no real intention of claiming the island for themselves. In an act of good faith, he immediately reinstated some of the French officers that had been dismissed by Governor Laigret.

More of a threat to French rule than America’s future ambitions was a movement by the New Caledonians themselves for autonomy. The autonomists wanted a greater say in running their own affairs while the native Kanaks and small Asian populations did not want to go back to the former status quo where they had no political voice and earned generally low wages.

In March 1944, when the Solomons campaign ended, American troops began moving most of their equipment and supplies out of New Caledonia to forward bases. The Navy gave up consideration of Nouméa harbor as its main base, instead shifting its repair facilities to Ulithi Atoll in the Caroline Islands. On June 15, as the war moved north and west, Halsey left New Caledonia. As he was being driven through the streets of Nouméa toward a waiting plane, soldiers, sailors, and townspeople lined the roadway. “Their cheers and the bands and the flags stung my eyes,” Halsey wrote. “I never saw Nouméa again.”

As Admiral Nimitz continued his island-hopping campaign through the Central Pacific and General MacArthur drove his troops toward the Philippines, New Caledonia fell into the quiet backwater of the war. Commented the new Australian consul to the island in August 1944, “New Caledonia has completed its transition from a combat base to a supply base and hospital center.” The tiny French colony had been transformed into a place of “rest and relaxation” for American troops back from the front lines.

For the next year, until the war ended in September 1945, Governor Tallec walked a fine line to keep New Caledonia under French control. Due to the many disingenuous reports of High Commissioner d’Argenlieu and the various governors, General de Gaulle had been led to believe that the people of New Caledonia were secretly anti-American and openly pro-French. He could not understand why, once the Americans left, the New Caledonians did not rush back to the Free French. In reality, many of the island people felt that the Gaullist authorities treated them as second-class citizens, and they did not want to return to business as usual.

Although the Americans had moved on, their presence on the island was still being felt years later. Prosperity brought on by the Americans led to better wages and better working conditions. Roads had been improved, telephone wire had been strung, and Nouméa harbor had been expanded. Additionally, many buildings that had been constructed for use by the U.S. Army or Navy were now available for the people of New Caledonia. Recognition of Kanak and Asian rights by the United States military led to their demand for a voice in the government. In 1946, New Caledonia was granted the status of an overseas territory of France, and seven years later French citizenship was granted to all islanders, no matter their ethnicity.

By the end of World War II, most Americans felt that their presence in New Caledonia had kept the Japanese from invading the island. They likewise felt that they had been little appreciated by the Free French forces on New Caledonia and abroad. On the other hand, the Free French felt that they had acted as reasonable hosts to the Americans, giving them the use of New Caledonia so that they could defeat the Japanese in the Solomons. Without New Caledonia, some of them felt, victory in the Solomons would have been impossible. Many Free French felt exploited and unappreciated by the Americans.

In reality, all sides benefited from the interactions between the Free French, the New Caledonians, and the Americans. Although egos had been bruised and times had been turbulent, all three factions had managed to come together, succeeding in accomplishing their common goal, the protection of New Caledonia and the defeat of Imperial Japan.

Author Gene E. Salecker is a retired university police office who teaches eighth-grade social studies in Bensenville, Illinois. He is the author of four books, including Blossoming Silk Against the Rising Sun: US and Japanese Paratroopers in the Pacific in World War II. He resides in River Grove, Illinois.

This is a good read. My Dad served with Army Americal Division artillery on Guadalcanal. He met and married Mom in Noumea. I only wish you had included more about Army Americal Division artillery.

My dad fought on Guadalcanal and had a couple of R&R tours on New Caledonia. He said the people there were nice to him and other GI’s during their time on the Island. Have never been a de Gaulle supporter and this article does nothing but reinforce my feelings.

My father spent three weeks in Noumea before shipping out to Efate in May of ’43. He worked there for 18 months building roads and other infrastructure until the war passed the area by and the island was pretty much stripped of personnel, some of which were sent north to Leyte to stage for the Okinawa invasion. It’s where my father finished the war, working the beaches unloading and distributing cargo.

Most significant source of political problems between US and France was opposite expectations of a post war world. France expected a return to the status quo ante complete with colonies and Roosevelt was essentially anti-colonial. Turned out that both were not exactly prescient in their viewpoints. Independence did come over a period of two decades after the war to most European colonies but with woefully inadequate preparation. The effects of which redound to this day in a number of former colonies. The US was fortunate to escape most of conflicts despite occasional grumbling from Puerto Rico and demands from Northern Marianas to be better treated in relations with Washington.