By Jim Haviland

Early in the American Civil War, during the first months of 1862, Union General Henry Halleck, commanding from his headquarters in St. Louis, was increasingly concerned, then downright agitated. His subordinate, General Ulysses S. Grant, wasn’t responding to his orders. Halleck, who had graduated from West Point in 1839, the year of Grant’s arrival, finally became so annoyed he recommended that Grant—a Northern hero owing to his recent victories at Forts Henry and Donelson—be removed from command. Halleck launched an investigation to find out why the brigadier general, then directing an advancing Union army farther into Tennessee, was ignoring the orders telegraphed to him.

The upset Halleck wired Grant to place Brig. Gen. C.F. Smith in command of the Union advance and then ordered Grant to quarters at Fort Henry. He added: “Why do you not obey my orders and report the strength and positions of your command?”

Grant was completely mystified. He knew nothing about the orders Halleck reportedly had telegraphed from St. Louis. But Halleck believed he already knew the answer; he alluded to it in a telegram informing General George McClellan of his action. “A rumor has just reached me that since the taking of Fort Donelson, General Grant has resumed his former bad habits,” he wrote. “If so, it will account for his neglect of my often-repeated orders.” McClellan would have known to what Halleck was referring, that Grant was off on a bender.

“I do not deem it advisable to arrest him [Grant] at present,” Halleck wrote McClellan in his message, “but have placed General Smith in command of the Tennessee expedition. I think Smith will restore order and discipline.”

Grant hadn’t done any of the things Halleck accused him of, and said so in a telegram to his superior after complying with instructions to turn over his command to Smith. “I am not aware of ever having disobeyed any order from headquarters,” Grant insisted. “Certainly never intended such a thing.”

Halleck’s messages to Grant were being sent to a telegraph operator in Cairo, Ill., at the end of an advancing telegraph line. Halleck’s investigation of the unanswered orders soon bore fruit when it was discovered that the Cairo operator was a Confederate spy. Rather than forwarding the orders on to Grant, he pocketed them. Then he skedaddled back to the South with all of Halleck’s orders.

The young Confederate’s real name was never discovered, but he effectively disrupted the Union command in the West and caused an uproar at headquarters in St. Louis. Nor was that the end of the trouble. Seething over Halleck’s attempt to find fault with him, Grant asked to be relieved of further duty until a higher authority completely cleared him.

Finally aware that Grant was innocent, Halleck sweetened his response, claiming there was no good reason to relieve Grant of command. Halleck, in fact, had heard that Confederate General Pierre T.G. Beauregard had been reinforced by 20,000 troops and reportedly was entrenching them around Corinth in northern Mississippi. That meant difficult battling and Halleck wanted Grant, his hardest-fighting general, in command. So he convinced Grant to board a steamboat at Fort Henry and head out on the Tennessee River to rejoin his army. This Grant did. Then he, his determination, and fate took him to ultimate Union victory and presidency of the United States.

More Than a Novelty

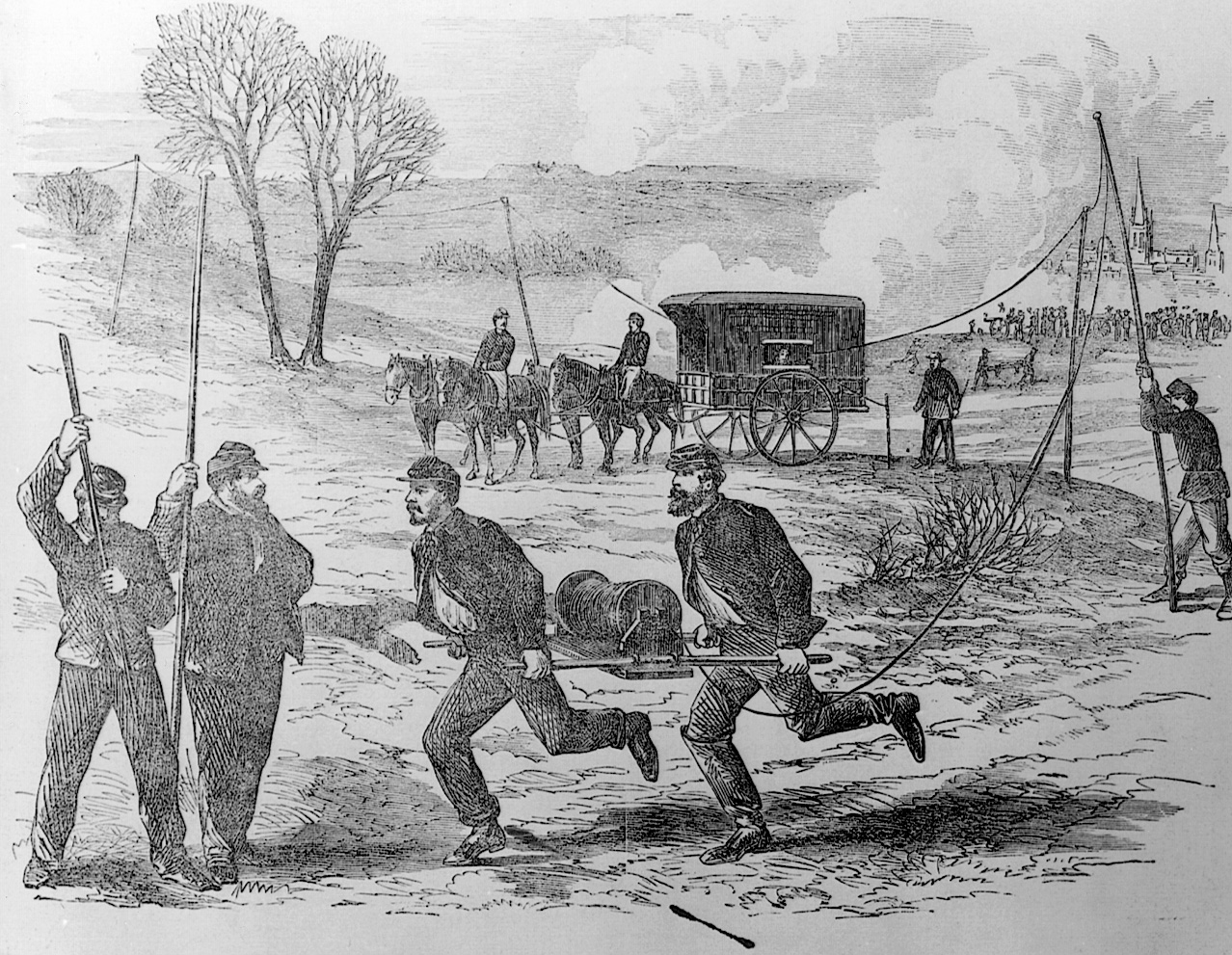

But this episode was far from the end of telegraph shenanigans in the struggle between North and South. For the first time in a major conflict, both sides were using the new telegraph system extensively. It was such a new military tool that Union forces had to post sentries along the telegraph routes—not only to protect the lines from sabotage, but also to guard against Union soldiers who kept cutting the wire to send pieces home as war souvenirs.

The telegraph was invented by painter Samuel F.B. Morse, who filed his patent in 1837, only 14 years before the outbreak of the war. He sent messages over the electromagnetic device in a code comprising short and long bursts of electricity bearing Morse’s name. Suddenly people could communicate in an instant over long distances. No other instrument quite shrank the world so dramatically. For this, and some other new technologies, the American Civil War has been called the first modern war.

With respect to the telegraph, the North had a head start. At the beginning of the war, it had an extensive telegraph network in place, providing a rapid means of moving intelligence and orders. The South understood the value of the telegraph as well as the North, but did not enjoy an extensive network at the war’s opening, nor could it develop one, owing mainly to a lack of wire.

The telegraph, of course, had its negative aspect. It could be cut or tapped. Or, as in the case of the Cairo operator, its messages could be stolen and never delivered. Both the North and South tapped into enemy telegraph lines with varying success. While the Union could and did read Confederate cipher messages, the Rebels never succeeded in deciphering any coded Federal messages after tapping into the important line running from Grant to President Lincoln after the general had been transferred to Virginia and placed in overall command.

With an inventive mind, Lincoln encouraged his troops to use balloons for needed battlefield observation of Southern positions. Balloonist Thaddeus Lowe then set to work linking the balloons and the telegraph, setting up the first air-to-ground telegraphic communication on June 18, 1861, in Virginia. But with hot air balloons providing too good a target for Confederate soldiers to down with their new rifled muskets, balloon and telegraph use was abandoned by Federal forces early in 1863.

Some spies quickly learned how to effectively use the new telegraph system to transmit purloined information back to an appropriate military command. And both Union and Confederate espionage agents listened in on enemy telegraph communications. Confederate General Stonewall Jackson ordered his troops to cut Union telegraph lines to disrupt Federal communications during his May 1862 campaign in Virginia’s Shenandoah Valley. And he used the Rebel telegraph line to secure General Robert E. Lee’s permission before finally moving to capture Front Royal.

In 1863, two Union sympathizers, F.S. Valkenbergh and Patrick Mullasky, successfully tapped into a Confederate line along the Chattanooga Railroad near Knoxville, Tenn. This allowed them to supply vital information to Union General William Rosecrans about Confederate General Braxton Bragg’s Rebel troop movements to reinforce Vicksburg on the Mississippi River.

But serving as a telegraph spy was dangerous, as William Forster, a Union operative, found out. He successfully tapped into the Confederate line for two days along the Charleston-Savannah Railroad. Rebels caught him and threw him in prison, where he died.

The Telegraph Spy: J.O. Kerbey

An early Northern telegraphy spy was J.O. Kerbey. Like many telegraphers (including Andrew Carnegie), he was trained for the railroads in their days of expansion before the Civil War. Kerbey volunteered to serve as a Union spy and sneaked behind Confederate lines before the Battle of First Manassas in July 1861. While checking out the Shenandoah Valley on foot, Kerbey spied Confederate General Joseph Johnston beginning to move his troops forward in support of General Beauregard, who was awaiting a Union advance against his position at Bull Run.

Slinking away to find Union forces, he immediately told a ranking Federal officer about his observations of the Confederate troop movements. But the Yankee didn’t believe Kerbey, and Johnston’s advance went largely unchecked—the Union subsequently was defeated at First Manassas.

Although failing in his first spying attempt, a determined Kerbey returned behind enemy lines until unexpectedly being picked up by Confederate troops. The frightened spy thought quickly and informed the Rebels of his telegraphy skills. The Southerners assigned him duty as an operator in a Virginia railroad station not too far from Richmond, trained operators being scarce in the South. From that station, Kerbey listened to telegraphic communications in and out of Richmond. Piquing his interest one day was a message reporting that a quarter of the Southern troops in the Manassas area had dysentery. Considering this an opportune time for a Union assault, he hid the information in his hatband and tried to slither off toward Union lines. But Confederate troops turned him away.

Because of this difficulty in trying to move on foot to Northern positions, Kerbey decided he needed a better way of relaying his information to Federal authorities. After a transfer to Richmond proper, he learned Elizabeth Van Lew was a key Union spy in the Rebel capital. Shortly thereafter he began to send his intelligence through Van Lew’s couriers and using Van Lew’s cipher system.

One valuable piece of information he picked up as a telegraph operator and sent north through Van Lew’s couriers enabled Union forces to break up a group of Confederate sympathizers operating out of a Georgetown University dormitory. The collegians were raising and lowering shades at night in their room, and thus sending signal messages across the Potomac River to Rebel spotters on the other side.

Kerbey Becomes a Double-Agent

When Southern manpower shortage became critical, Kerbey was recruited away from his telegraph key and into the Confederate Army. Immediately he was forced to sign a Loyalty Oath. When his Southern unit moved north, Kerbey waited for an opportunity to slip away and return to the Union side and again become a telegraph operator.

He did manage to desert the Confederates for the Union Army. All was fine until he was asked to sign a Union Loyalty Oath specifying that he had never carried arms against Federal troops or signed a Loyalty Oath to forces opposing the Union. Being honest, Kerbey said he couldn’t sign the oath, explaining the reason. He was confident that Secretary of War Edwin Stanton would be aware of his Union spying activities and thus solve his problem.

But Stanton didn’t help. Instead, the Union official ordered Kerbey arrested and thrown into Old Capitol Prison in Washington. This was a setback indeed, but in prison Kerbey met fellow inmate Belle Boyd, a famous Confederate spy. Boyd had heard about Kerbey’s arrest on Stanton’s orders. Deciding to help Kerbey because she deemed him valuable to the Confederacy, Boyd began assisting the anxious telegrapher in an escape plan. She even told him about “safe houses” along a special route back to the Confederacy once he had fled the prison. Although worried what might happen, Kerbey decided to play along with her plans because he knew her information about the “safe houses” would be valuable to the Union Secret Service.

The day his escape was scheduled, Kerbey unexpectedly was removed from his cell and freed—Stanton had finally realized his mistake. Boyd never knew what happened to the telegraph operator nor did she understand that passing along information about the “safe houses” was a dire mistake.

Because of the danger of Kerbey being recognized as a Union spy if he continued his service in that capacity, it was decided he should leave espionage and become a lieutenant in the regular Union Army—his commission was personally signed by President Lincoln. But his service for the Union as a regular soldier did not bring Kerbey the notoriety he had achieved as a spy, and he soon faded from prominence. Nevertheless, he had gained a unique place in U.S. history as the first signals intelligence operator on record.

Morgan and Ellsworth: Confederate Telegraph Spies

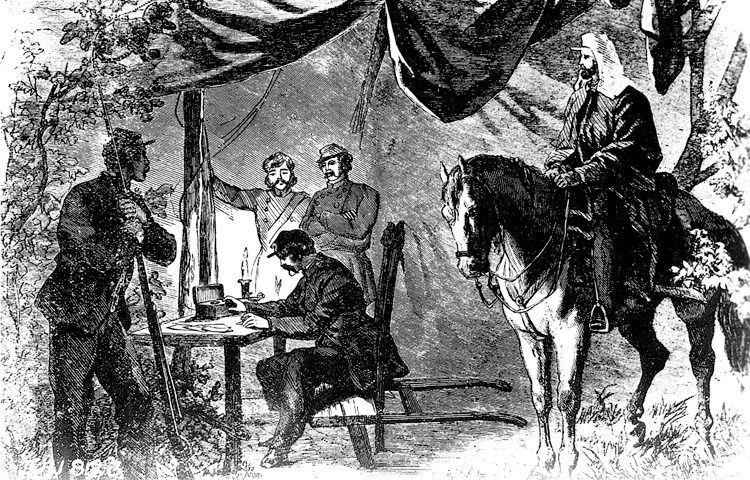

Confederate cavalry commander and swaggering personality John Hunt Morgan was also a strong believer in the value of the telegraph, and frequently used it to improve his chances for success during his raids. He was aided in this regard by skilled telegraph operator George “Lightning” Ellsworth. (He earned his sobriquet for fearlessly climbing a telegraph pole during a storm, only to be knocked to the ground when lightning struck.)

Ellsworth climbed poles during Morgan’s raids and tapped Yankee lines. Thus Morgan often discovered enemy plans and troop movements. As important, he was able to discover what Union troops knew of his own movements. The dashing Rebel cavalry commander also successfully used Ellsworth to send misinformation in bogus messages to Federal authorities about dispositions.

During one raid through Kentucky, Morgan had Ellsworth send gloating telegraph messages from him to selected officials and persons of influence. One reached a surprised George Prentice, the pro-Union editor of the Louisville Journal, who had belittled Morgan in print. With Ellsworth’s help, the Confederate commander harangued Prentice on July 22, 1862, from Somerset, Ky. “Good morning, George D.,” his message began. “I am quietly watching the complete destruction of all of Uncle Sam’s property in this little burg. I expect in a short time to pay you a visit and wish to know if you will be at home. All well in Dixie.”

Another telegraph message from Morgan reached Brig. Gen. Jeremiah T. Boyle, Kentucky’s military governor, in Louisville. “Good morning, Jerry,” it read. “This telegraph is a great institution. You should destroy it as it keeps me posted too well. My friend Ellsworth has all your dispatches since July 10 on file. Do you wish copies?”

In July 1863, Morgan’s column entered Bardstown Junction along the Louisville & Nashville Railroad—about 25 miles south of Louisville. There Ellsworth entered the Bardstown Junction telegraph office and found operator James Forker wearing a uniform recently issued to Union telegraphers. It included a dark blue blouse, blue trousers with a silver cord on the seam, a natty buff vest, and a forage cap with no ornaments or marks of rank. Putting his pistol to Forker’s head, Ellsworth said: “Move one inch except as I tell you and you’ll be buried in that fancy rig you’re wearing.”

Listening to incoming messages, Ellsworth learned that Morgan was expected to attack Louisville. He also learned about a Union passenger train due to come through Bardstown Junction from Nashville. When the railroad superintendent in Louisville asked the Union telegraph operator if the train had passed north yet, Ellsworth told Forker to tap out “yes.” Forker did as he was ordered, and in a few minutes the train was surrounded by Morgan’s gray-clad troops south of a trestle that the raiders had set afire. In an exchange of gunfire, one Union soldier was killed. The surviving 30 passengers and a dozen soldiers were ordered to disembark and line up beside the tracks. They were relieved of hats, boots, money, and jewelry. Raiders also broke into the express company’s safe to remove money. Morgan, dressed in a roundabout jacket, gray trousers, and cavalry boots, and wearing no insignia of rank, chatted with the women passengers. They persuaded him to allow the train to return south to Elizabethtown. One woman praised General Morgan, calling him “a gentleman,” unaware that she was speaking to the general in person.

Another Confederate telegraph spy was C.S. Gaston, who successfully tapped into a Union line while using a location disguised as a logging camp. There he was fortunate to get into the wire connecting Grant’s headquarters in Virginia to President Lincoln, who recognized the telegraph’s great value in enabling him to personally direct his Federal commanders in the field.

During a two-month tap, the Rebels were unable to decipher any of the Union’s coded messages. But Gaston found the uncoded ones helpful. One reported that a large quantity of beef was scheduled for landing at Coogins Point on a particular day to supply Union troops. This information was passed on to Rebel cavalry commander Wade Hampton. The South Carolinian used it to capture the entire food shipment, much to the later benefit of hungry Confederate troops.

As valuable as the telegraph was to knowledgeable persons North and South, the new technical device was largely unknown to common soldiers. One was a Texan in the Confederate Army who came across an abandoned receiving unit while wandering through a deserted railroad station in the Western theater late in the war. The receiver was loudly and rapidly clicking, an operator sending a message from farther down the railroad line.

The Texas soldier had never seen such a crazy-looking and clacking device before and imagined it as some sort of infernal weapon. Wanting to save his friends despite the presumed risk to his own safety, he quickly used his heavy boots to smash the clattering instrument.

He then rushed to his comrades with the good news. “Boys, they is trying to blow us up,” he declared. “I seen the triggers a-working, but I busted ’em.”

Join The Conversation

Comments