By Kelly Bell

On May 4, 1943, the U.S. Army Air Forces’ 56th Fighter Group was ordered to meet a formation of Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress heavy bombers returning from a run over Antwerp, Belgium.

Colonel Hubert Zemke, commanding the American fighters, lost his radio communications as he reached the Dutch coast, forcing him to hand over command to Colonel Loreen McCollum, commander of the 61st Fighter Squadron and return to base. It was Zemke’s second aborted fighter mission due to radio failure, and since he was unable to inform his men as to why he left he was concerned they would misconstrue his departure as cowardice. After arriving back at his base outside the English town of Horsham St. Faith, he vented his wrath on the hapless mechanics. His radio would not break down again.

Meanwhile, his squadron met the B-17s over the German coastline. As the bombers passed over Walcheren Island a squadron of Focke-Wulf FW-190 single-engine fighters assaulted them. McCollum eagerly turned his flight toward the approaching “Butcher Birds” and attacked. Latching onto the tail of a fighter, he opened fire and was thrilled when it exploded into flames under his Republic P-47 Thunderbolt’s brutal pounding, but as he eagerly watched the stricken aircraft plummet he was horrified to realize it was not German. Flushed with the exhilaration of his baptismal dogfight, McCollum had attacked the first aircraft he saw and shot down a British Supermarine Spitfire.

Despite his absence from the engagement, Zemke’s status as group commander made him liable for the tragedy, and it was he who was summoned to 1st Fighter Command headquarters to answer to a livid Brig. Gen. Frank Hunter. Nevertheless, although he was just getting started in World War II combat, Zemke had already come a long way.

Hubert Zemke: An Experienced American Fighter Pilot

When Lieutenant Hubert Zemke had reported to the 56th Fighter Group in March 1942, he was a priceless commodity to his country in this new war. After spending the past two years overseas training British, Russian, and Chinese pilots to fly the Curtiss P-40 Tomahawk fighter, he was a rare and sorely needed gem—an experienced fighter pilot.

At the end of June, he was promoted to major and given command of the 56th’s newly formed 89th Squadron. The ex-boxer from Montana was finally back in the ring, but this time the stakes were much higher than in his earlier bouts.

Soon after his advancement to major, Zemke was promoted to lieutenant colonel and made group commander. Six months earlier he had been an obscure lieutenant with nobody to give orders to, but he had no time to be overwhelmed by his vastly expanded status and the pressures that came with it. The group’s aircraft were arriving.

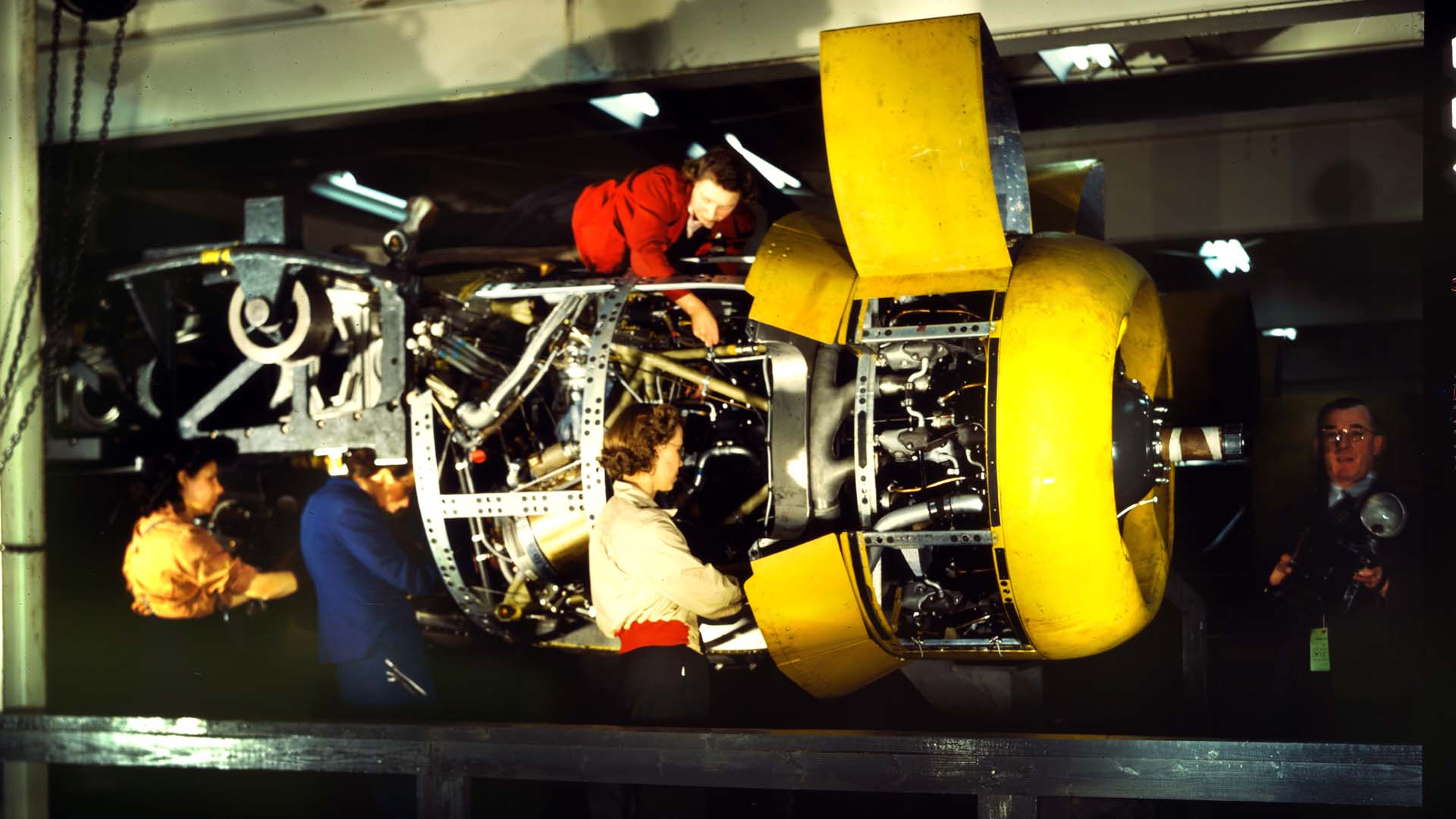

For the rest of 1942, Zemke and his fellow group commanders relentlessly drilled their men in their new Thunderbolt fighters in preparation for the inevitable day when they would be called on to face the polished pilots and sleek flying machines of Germany’s renowned and feared Luftwaffe. Word came on Thanksgiving Day. The 56th was officially alerted that overseas transport was imminent.

The pilots and ground crewmen arrived (without their aircraft) in England just after the new year, and like most Yanks these newly arrived young fliers were impatient. As days kept passing with still no sign of their planes, their agitation mounted. On January 24, 1943, two full weeks after the 56th’s arrival, the first machines were delivered. Within a few days the group was fully equipped, and the men were testing their planes and themselves in the dreary English skies. By spring it was time to fight.

For the bulk of April, the 56th, 61st, 62nd, 63rd, and 4th Fighter Groups made relatively short-range “rodeo” sweeps over coastal areas of occupied France in attempts to lure enemy fighters away from the routes of B-17s and Consolidated B-24 Liberator bombers. The Germans rarely accepted fighter combat, preferring to go after the bombers.

On May 9, Zemke received notification of his promotion to full colonel. This action was a policy matter in which senior commanders received promotions more or less automatically so there would be room for the advancement of junior officers. In most cases this would be a pleasing but unsurprising event for a man in Zemke’s position. However, the fact that his command had no German kills (only a British one) so far fueled already widespread derision of the 56th as the European Theater’s black sheep outfit, and any of its personnel being promoted came as something as a surprise. The 29-year-old colonel and his men were grimly resolved to shake off their reputation. It would not take long.

First Kills For the 56th

Things started to look up on June 12 when McCollum led a sweep over Belgium and closed with a hostile flight. Captain Walter Cook knocked down an FW-190 for the 56th’s first confirmed kill. The next morning Zemke and eight of his men waylaid a formation of unsuspecting Focke-Wulfs that were climbing to attack another Thunderbolt flight. Leading the charge, Zemke shot down two planes while Lieutenant Robert Johnson got a third.

When Zemke was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross on July 19, he figured he had better make sure nobody thought it was merely to boost morale. He put his pilots through such intensive flight training that headquarters called to learn why the 56th was using so much more fuel than the other groups. It would be gasoline well spent.

The Luftwaffe’s policy of avoiding combat with the U.S. fighters backfired. The Germans had refused to accept battle with inexperienced fliers. These men were now becoming battle tested, dangerous pilots.

On the afternoon of August 17, Zemke and one of his squadrons headed east to meet and escort home a flight of B-17s returning from the costly first raid on the Schweinfurt ball bearing factory. Their range extended by exterior fuel tanks, the P-47s made it as far as Antwerp before they had to switch to their interior fuel supply.

Soon after jettisoning their empty tanks, the American fighters encountered the surviving homebound B-17s under heavy fighter attack. The Germans were not expecting to encounter Thunderbolts so far east and were taken totally by surprise. Zemke immediately downed a Messerschmitt Me-110 twin-engine fighter as the sprawling dogfight commenced, and the 56th drove the enemy from the battered bombers.

The group destroyed 17 enemy fighters, damaged nine, and had one probable in exchange for one lost and two missing. The news that the 56th had accounted for all but two enemy kills that day further bolstered the pilots’ soaring confidence and morale. When they learned one of their victims was renowned Major Wilhelm Galland, commander of II Squadron of Jadgergeschwader 26 with 55 kills of his own, the young Americans knew the enemy was theirs. At this point some enterprising individual first referred to the 56th as “Zemke’s Wolfpack.” The moniker stuck.

Schweinfurt Raid Disaster

With his fifth kill on October 2, 1943, Zemke became an ace. On bomber support missions during the month, the 56th shot down 29 German planes. The Luftwaffe ruefully noted this success and withdrew its squadrons from coastal areas, clustering them around likely bombing targets. On October 14, while Zemke was at Eighth Air Force headquarters receiving a British Distinguished Flying Cross, his men went aloft to escort bombers on the ill-fated second Schweinfurt raid. The Germans waited until the P-47s were nearing their range limit then attacked in force. They shot down 60 B-17s against a loss of just 13 of their fighters.

This debacle sobered Zemke and his men. It jarred them into the realization that the Luftwaffe was far from beaten, and it was a grim 56th that took off November 5 on a vital bomber support mission to Munster. Rendezvousing with the B-24s over the Zuider Zee, they were one of eight fighter groups sent up in relays to provide the Liberators with near continuous protection. As it neared the target, the formation encountered a flight of 30 rocket-armed FW-190s.

As the Germans assembled to attack the bombers they never thought to look above and to either side of their targets, where the vengeful Wolfpack lurked. Nothing in the sky was as fast as a diving Thunderbolt, and these were diving as they tore into the enemy formation from both sides.

Plunging out of the sun, Zemke and his flight knocked down two bandits on their first pass, scattering the rest. They encircled the bombers in a protective swarm, shooting down six interceptors and losing just one B-24. The day’s work brought the 56th’s tally to 102 kills.

Zemke’s Stateside Speaking Tour

Despite the stunning success of the 56th and other U.S. fighter groups late in 1943, the Eighth Air Force bomber wing was slowly bleeding to death. Its fleets were being decimated in the constant, crucial raids on Hitler’s industry, and the flow of replacements could not keep up with the rate of attrition. Back in Washington there was a feeling in some quarters that the Britain-based strategic bombing offensive was a failure, and some sorely needed planes and crews were diverted to Italy to comprise another bomber wing. There was also a faction favoring the virtual abandonment of the war in Europe and total concentration on the war with Japan.

The men at the front could see the threat still posed by Nazi Germany despite its recent reverses in Russia and Africa. Giving Hitler respite now could prove suicidal. His scientists were working on a new generation of revolutionary weapons the Allies could not afford to allow to come into widespread use. The Fortresses and Liberators had to keep the pressure on the Third Reich, so the high command organized a lecture team to tour the States and drum up support for the European bombing offensive. Since he had come to be regarded as the top fighter commander in Europe, Zemke was included in the group.

The young war hero was unhappy about leaving his command just as it finally had achieved such a high degree of effectiveness, but he could not deny the importance of this assignment. Support for the European air war was at a critical low, and the controlling interests had to realize the absolute necessity of taking the fight to the enemy’s heartland and destroying his ability to support his armies.

Zemke and his lecture team did an excellent job of impressing on the politicians and voters the need for a continuing air war against Hitler. By Christmas the continued flow of men and aircraft to Europe was assured.

“Get Back to Halesworth.”

Just after the new year, Zemke reported to the Pentagon for his orders back to his base at Halesworth Airfield in England but was informed he was to be reassigned stateside to the Directorate of Operations of the First Air Force at Mitchel Field. The army was absurdly trying to consign Zemke to a desk. He had no intention of allowing it.

Since he had not yet received written orders for his new posting, Zemke saw an escape route. He still had his original written orders which stipulated he was to return to his command in Britain after the speaking tour, so he caught a cab to Andrews Field where he showed these papers to an Air Transport Command clerk without telling the man they were obsolete. The clerk directed him to an empty seat on a C-54 transport plane bound for Britain. Later presenting himself at the office of his commanding officer, General Bill Kepner, he truthfully informed the general he was reporting for duty as per his original orders, and that he had not received any subsequent written orders. Kepner also regarded this new assignment as ludicrous and went all the way to Eighth Air Force commander General Jimmy Doolittle to have the stateside posting rescinded.

At Kepner’s suggestion, Zemke made himself scarce until the matter could be settled. He hid out in Edinburgh, Scotland, for a week, after which Kepner summoned him and told him merely, “Get back to Halesworth.” Zemke did so without asking questions. Things were changing, though.

200th Kill on FDR’s Birthday

Zemke was one of the few Thunderbolt pilots to recognize the potential of the North American Corporation’s new P-51 Mustang fighter, and had he been present at the time of their delivery, the Wolfpack would have been one of the six fighter groups that switched from the Thunderbolt to the Mustang.

Under McCollum’s command the 56th had continued to perform superbly, notching 80 more kills and setting a one-day record with 23 on November 26. McCollum was not on hand to greet his returning chief. He had been shot down by antiaircraft fire and captured a few days earlier. Yet the Wolfpack did not let his loss slow its depredations.

Despite the Luftwaffe’s ever greater efforts to avoid the increasing numbers of diversifying Allied fighters over Europe, the 56th scored its 200th kill on January 30, dedicating it to President Franklin D. Roosevelt on his birthday. That same day the 4th Fighter Group, in second place, claimed its 100th victory. Still, the Wolfpack’s days at high altitude were numbered.

In February the 56th commenced serious ground attacks, concentrating on airfields despite their notoriously deadly antiaircraft defenses. The Thunderbolt’s extreme toughness and pulverizing firepower made it the obvious selection to send after the dwindling Luftwaffe on the ground.

“Happy Hunting Ground”

At the end of the month, the group took time off from strafing and dive bombing for Big Week. With preparations for the Normandy invasion underway, the high command was giving neutralization of the Luftwaffe top priority. Attacking the problem at its source called for heavy bombing of airframe and engine factories. With the arrival of optimum weather on the 20th, the Italy-based Fifteenth Air Force joined the England-based bomber wings in a major offensive against aircraft production facilities in Schweinfurt, Hanover, and other targets in the region of central Germany that Zemke and his Wolfpack had come to call their “Happy Hunting Ground.”

Aided by new, pressurized 150-gallon drop tanks, the group ranged deeper than ever into enemy airspace, marvelously protecting the B-17s and B-24s. From February 20 to 25, the 56th lost two planes and shot down 72. Its domination of the German skies was so total that the bulk of the damage to its planes came from flying through debris from exploding enemy aircraft. Also, the quality of the German pilots was declining due to attrition. The Me-109 was not an easy plane to fly, and training men for it took time that the reeling Reich no longer had. The strain on the Luftwaffe was never so apparent than when, on the last major raid in February, Zemke and his fliers encountered no enemy interceptors as they escorted bombers to Brunswick.

However, on March 6, American bombers made their first major strike on Berlin, and swarms of Germans rose in desperate defense of their capital. Perhaps a spy had tipped them off to the coming raid and they clustered their remaining veteran squadrons around Berlin, but regardless of how they did it their performance was lethal. The Eighth Air Force took its worst pounding of the war, losing 80 planes, 69 of them bombers, on that one mission.

Two days later the heavies resolutely hit Berlin again, and the Wolfpack stayed busy as the enemy threw everything it had at the bombers. With 27 kills, the 56th accounted for more than a third of all aerial victories made by Eighth Air Force fighters that day, becoming the first fighter group to reach the 300 mark.

38 Aces in the Wolfpack

Following the fruitful first days of the month, severe weather grounded the air war over Europe. Zemke was stunned on March 14 when Generals Kepner, Doolittle, and Carl Spaatz arrived at Halesworth and decorated him with the Distinguished Flying Cross. During the next few days he would earn it all over again.

On the 15th and 16th, the group knocked down 32 Germans while losing just one of their own. It was a performance they were making seem commonplace, but their days of freewheeling mastery of aerial combat were drawing to an end.

The Mustang was easing the Thunderbolt out of escort duty. These new P-51s did not leave much aloft for the P-47. The increasingly frustrated Wolfpack grew weary of patrolling skies devoid of targets and took its frustration out on ground marks. Railways, shipping, airfields, and truck convoys became the main victims of the Thunderbolts’ .50-caliber machine guns. The main danger now was also on the ground. Several high-scoring veterans wound up dead or as prisoners when they strayed too near the flak pits. Still, on July 4, 1944, the group surpassed the 500 mark. There were 38 aces in the outfit.

As the fighting in France progressed, the 56th became as proficient at ground attack as it had in aerial combat the previous year, but there was too much of the gladiator in Zemke for him to be fulfilled by shooting up locomotives and parked cargo planes. When the commander of the rookie 479th Fighter Group was killed in action on August 10, Zemke applied for the vacancy and was quickly accepted.

Transferred to the 479th

After its arrival in May, the 479th had been too quickly hustled into combat to give it some crucial battle seasoning before the Normandy invasion. It had so far shot down just 10 Germans while losing 35 of its own. By September, Zemke had his new command of Mustang wranglers believing in themselves. One of his men had even achieved ace status. In a massive dogfight over the Arnhem battlefield in September, the 479th shot down 29 planes while losing just one.

Despite air superiority, the onrushing Allies were bloodily halted at Arnhem, and it became apparent that the European war would not be over by Christmas as so many had hoped. If nothing else, this setback gave the 479th time for more seasoning, and its colonel was able to get back to his passion of escort duty. It was not quite the same.

Zemke and his fliers began to encounter strange jet aircraft and others that looked like rocket-powered gliders. These developments, however, were coming too late to impact the outcome of the war in favor of Germany.

In October, Zemke was again informed he was slated for a desk job. With 19 confirmed kills and now in a position to add to this total, he remained emphatically disinterested in a paperwork career and was busily scheming to avoid it and stay in the sky as he took off on his next patrol.

He was cruising for home with two of his men when an Me-262 jet fighter attacked them. Powering their Merlin engines to their fullest and twisting through an interminable series of gyrations, the trio of young Americans was able to avoid the jet’s deadly passes until the German ran low on fuel and departed. Unknown to Zemke, the wild maneuvers had severely weakened his Mustang’s structural integrity, and when he lifted off on October 30, 1944, on what was slated to be his last combat flight he did not suspect it would be one mission too many for his strained machine.

Captured by the Germans

The weather forecasters had goofed, and as the bombers and their escort penetrated German airspace they were forced to weave through masses of cumulus clouds. When the Liberators blithely flew directly into a particularly enormous cloudbank, Zemke and his flight had no choice but to follow.

Upon entering the clouds, the Mustangs commenced a violent bucking in the severe turbulence, so Zemke ordered a direction reversal. When he attempted to turn it, his P-51 nosed over into a tailspin, and as he tried to pull out the starboard wing buckled, slammed against the fuselage, and was ripped off by the wind. Over the next few seconds the plane simply disintegrated around the pilot, leaving him plummeting earthward in the seat to which he was still strapped. Kicking loose, he noticed his right arm was not functioning, so he pulled the parachute ring with his left hand.

After hobbling westward for two dreary, bone-chilling days Zemke despaired of reaching the still distant Allied lines. Becoming desperate for medical attention for his injured right arm and leg, severely bruised when the wing hit the side of the cockpit, he surrendered.

The Germans were intrigued by this youthful American who was so proficient in their language. This and his name made it easy to deduce his heritage, and realizing what a propaganda bombshell it would be if they could pull it off, they tried for a whole month to persuade him to come over to their side. All their cajoling, threats, wining, and dining were utterly unsuccessful, for Colonel Hubert Zemke would no more have considered taking up arms or a propaganda microphone against America than he would have against his own immigrant parents. This prodigal “son of the Fatherland” was 100 percent American.

By Christmas, Zemke’s disappointed captors had given up and packed him off to a prison camp outside the northern German town of Barth. Here he spent the remaining months of the war eagerly awaiting the arrival of his comrades from across the sea.

The desk job back at wing headquarters went to somebody else.

Let us not ever forget the courage and heroism displayed by the young fighter pilots of WW2!