By David Alan Johnson

As they boarded the train for Montreal, the two Americans tried to look as inconspicuous as possible. They were well aware that if they were caught they would be in trouble. At the very least, they would be sent back to the United States. There was also the possibility that they could be sent to prison, as well as fined more money than they had seen in their entire lives.

At the Canadian border, the train stopped and several sinister looking officials got on board. They wanted to know where the two were going and why.

“We’re on our way to Montreal to see a cousin who runs a fish hatchery,” was the reply. One of the unsmiling officials—probably an FBI agent—wanted to know if they were fliers. “Don’t be silly. Do we look like fliers?”

The officials were apparently satisfied by the reply. One of them opened the suitcases of the two travelers and rummaged through the top layer of clothing. He did not look any deeper. If he had, he would have found what he was looking for—flying helmets, goggles, and logbooks. Instead, he closed the lid and wished the young fellows a pleasant trip.

The two Americans, Eugene “Red” Tobin and Andy Mamedoff, were not smuggling contraband. They were going to Canada to enlist in the air force of a foreign country which, in the early weeks of 1940, was against the law. “The Federal Bureau of Investigation kept a pretty close check on all Americans going to Canada,” Red Tobin later said, “so we had to watch our step.”

During the 18 months before the attack on Pearl Harbor, from June 1940 to December 1941, several hundred American citizens volunteered to join the Royal Air Force. Some served in RAF Bomber Command as pilots, navigators, or air gunners with squadrons that flew Vickers Wellingtons or Avro Lancasters. Many were attached to Fighter Command and flew Supermarine Spitfires or Hawker Hurricanes against the Luftwaffe’s Messerschmitt Me-109s.

The Yanks who received the most publicity were the Eagle Squadrons, all-American units that served with RAF Fighter Command from September 1940 to September 1942. There were, however, other Americans in Fighter Command before the first of the three Eagle Squadrons was formed on September 19, 1940. These Yanks flew with all-British squadrons during the Battle of Britain in the summer of 1940. Most of them received no recognition at all—by their own choosing. The reason that most of these pilots kept their nationality a secret was a very practical one: They did not want the U.S. authorities to find out that they were American citizens.

In 1940, the United States was a neutral country and was determined to stay that way. Congress passed three Neutrality Acts in the 1930s. One of these acts made it a criminal offense to join the armed forces of a belligerent country, including Britain. It was against the law for an American to join the RAF. Anyone caught trying to join faced a $20,000 fine, 10 years in prison, and loss of U.S. citizenship.

Six potential volunteers from California found out about the Neutrality Act the hard way. They had been recruited by an RAF contact and, in late 1940, headed for Canada, their first leg on the way to England.

When their train made its first stop inside Canada, the six young fellows were met by two agents of the Federal Bureau of Investigation. The FBI men gave them a choice—either go back home or go to jail. The volunteers went back to California, but they tried again and succeeded in getting over to England the second time.

According to the official records of the Royal Air Force, only seven Americans served with Fighter Command in the summer of 1940. They gave their nationality as Canadian or said that they had come from one of the Dominions to get around the Neutrality Act. These seven American volunteers fought the Luftwaffe as members of RAF fighter squadrons.

Nobody knows how many pilots, officially listed as Canadians or from the Commonwealth, were actually American. Especially suspect are those with Anglo-Saxon names, like Johnson or Mitchell or Little. Ministry of Defense records list them as Canadian, which is no proof that they really were.

Pilot Officer Hugh Reilley was one such American pilot. He crossed into Canada and managed to get himself a Canadian passport, a highly illegal act. Nobody is quite sure how Reilley, who was born in the United States, obtained a Canadian passport. He made everyone connected to his little plot swear to secrecy. If either the Canadian or the American authorities ever got wind of it, those who helped him get the passport would be in serious legal trouble.

Reilley was commissioned as a pilot officer (the equivalent of 2nd lieutenant in the U.S armed forces) and was posted to 64 Squadron in September 1940. He was transferred to 66 Squadron later in the same month and took part in the great air battle of September 15, which has come to be known as Battle of Britain Day.

On September 19, Pilot Officer Reilley shot down a Messerschmitt Me-109. Three weeks later, Reilley was himself shot down and killed by German ace Werner Mölders. Because of his illegal Canadian passport, Hugh Reilley’s true citizenship was buried with him in a small churchyard in Gravesend, Kent, close to the airfield where he was based.

Another American in Fighter Command is mentioned by Pilot Officer Donald Stones of 79 Squadron. Stones remembered a Flight Lieutenant Jimmy Davis, “an American who had been commissioned in the RAF before the war.” According to Stones, Jimmy Davis was killed on the same day that King George VI visited Biggin Hill, 79 Squadron’s base, to award decorations. Davis was to have received the Distinguished Flying Cross that day. When the king asked about the remaining DFC on the table, he was told about Davis. Stones thought that the king was “quite moved.”

Actually, Pilot Officer Stones had his names confused, which was not difficult in those days when so many faces came and went as pilots were killed and replaced by other new faces. The pilot Stones had in mind was Jimmy Davies, who was born in Bernardsville, NJ, in 1913 and attended Morristown High School. Davies went to live in England in the 1930s, and took a commission in the RAF Reserve.

Davies is credited with shooting down the first German aircraft by a Biggin Hill-based pilot, in November 1939—a Dornier Do-17 “Flying Pencil,” a victory that he shared with a sergeant pilot named Brown. Although he has never been credited as such, Flight Lieutenant Davies is probably the first American ace of the war, having shot down eight German aircraft by June 1940.

There was an American pilot named Davis in Fighter Command in the summer of 1940, Carl Davis of 601 (County of London) Squadron. Davis’s parents were both American, but he was born in South Africa. There is also evidence that he became a British subject. When he joined the RAF, Davis emphasized the fact that he was born in South Africa. His brother-in-law, Sir Archibald Hope, the commander of 601 Squadron, probably also had a hand in getting Davis into the RAF. Between July 11 and September 4, 1940, he was officially credited with 11 German aircraft destroyed.

Number 601 Squadron flew Hawker Hurricane fighters from Tangmere in West Sussex. On September 6, two days after he shot down his last German airplane, Pilot Officer Davis was shot down. His Hurricane crashed, upside down, near the town of Tunbridge Wells, Kent. He is buried in St. Mary’s Churchyard in Storrington, West Sussex.

Other Americans undoubtedly served in Fighter Command as well. The only traces they left are their nicknames: Uncle Sam, America, or Tex. Because of the Neutrality Acts, there is nothing official that will reveal their real citizenship.

One American who did not make any effort to cover up his U.S. citizenship was Billy Fiske. Chicago-born William Mead Lindsley Fiske III was the son of a very wealthy international banker, attended Cambridge University, and married the former wife of the Earl of Warwick. During the 1930s, Fiske did weekend flying. With his connections, he had no trouble joining the RAF Auxiliary in 1940.

In July 1940, Pilot Officer Fiske was posted to 601 Squadron, the same unit as Carl Davis. Auxiliary squadrons were made up of wealthy and socially prominent young men. Number 601, nicknamed the “Millionaire’s Squadron,” was no exception. Its members wore custom-tailored uniforms, which featured tunics lined with red silk. “They were arrogant and looked terrific,” remembered Mrs. Fiske, “and probably the other squadrons hated their guts.”

Billy Fiske was well liked by the other members of his squadron. His commander, Archie Hope (who was also Carl Davis’s brother-in-law), said that Fiske was “the best pilot I’ve ever known.… He fitted into the squadron very well.”

During the Battle of Britain, Tangmere Aerodrome in West Sussex was 601 Squadron’s base. Operational fighter units, especially squadrons that were based so close to the Channel coast, saw combat every day that had flyable weather.

Pilot Officer Fiske shot down a twin-engined Junkers Ju-88 bomber on August 13, during one of his first combat sorties. Three days later, his own Hurricane was mauled by Messerschmitts while he was returning to base. Fiske crash-landed at Tangmere.

Flight Lieutenant Hope saw Fiske after he was taken out of the fighter’s cockpit and also visited him in the hospital that night. He did not seem to be badly hurt, only suffering from a burned face and hands. But, Hope recalls, “The next thing we heard, he was dead. Died of shock.”

Billy Fiske is usually referred to as “the first American to lose his life on active service.” He is certainly the first officially recognized American to be killed, but some of the U.S. citizens who entered the RAF disguised as Canadians may have died even earlier. Flight Lieutenant Jimmy Davies of 79 Squadron was killed on June 25, nearly two months before Billy Fiske. There may have been others as well.

Arthur Donahue, an American of humbler origins who became an RAF fighter pilot, described himself as “a farm boy” from St. Charles, Minn. Donahue went to Canada after Dunkirk and joined the RAF. He arrived in England on August 4, 1940, and was posted to 64 Squadron, which operated from Kenley Aerodrome south of London.

On his first operational sortie Donahue damaged an Me-109, after first making certain that it was not a British plane, and had his own Spitfire damaged by a German 20mm cannon shell. He managed to nurse his Spitfire back to Kenley, but it would need a new fuselage before it flew again. About a week later, he was shot down and wound up in the hospital. After he recovered, he was posted to the first all-American Eagle Squadron.

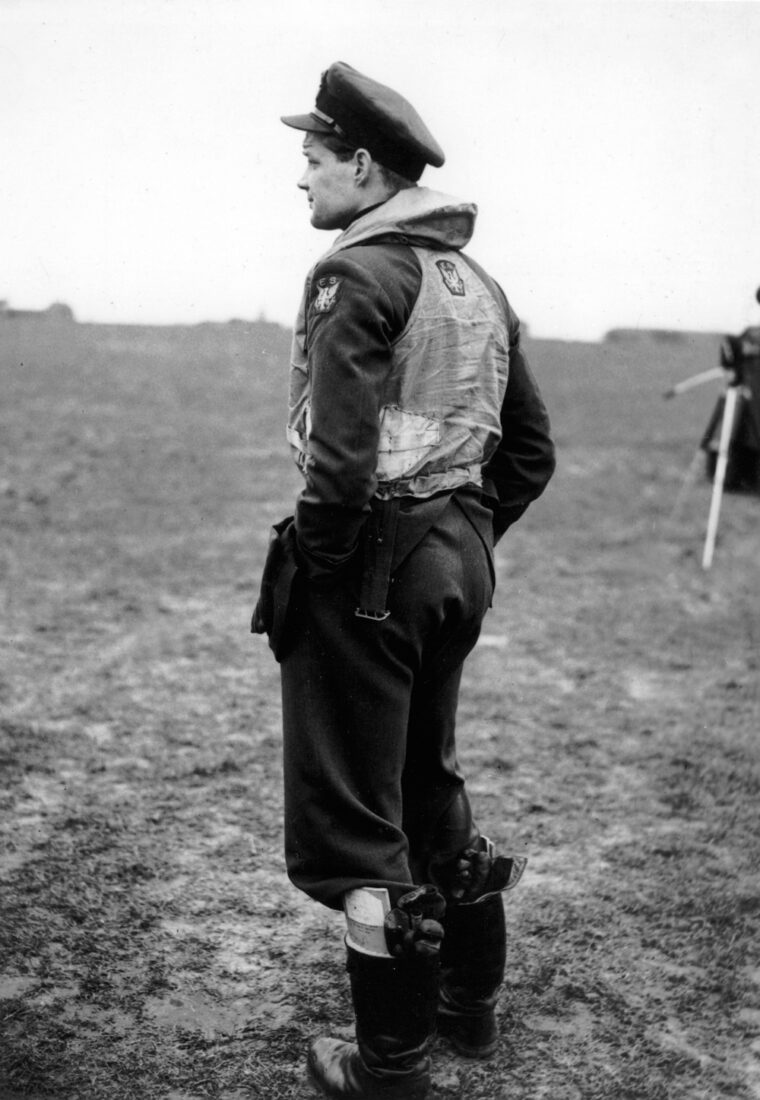

Andy Mamedoff, Red Tobin, and Vernon “Shorty” Keough were three Yank volunteers who served in the 609 (West Riding) Squadron. Tobin and Mamedoff met Keough in Montreal after they had talked their way past FBI agents at the Canadian frontier. The three of them traveled across the Atlantic together. They had been recruited into the RAF by Colonel Charles Sweeny, a wealthy American businessman who had family connections in London.

Sweeny had originally signed Tobin, Keough, and Mamedoff for the war between Finland and Russia, which began in 1939. However, the Finnish war ended early in 1940, before they had the chance to leave the United States. Undaunted and still looking for a fight, they joined the French air force, l’Armee de l’Air. They managed to get to France, which is where they were bound when they were traveling to Montreal, but France surrendered in June 1940, before they could do any fighting. The three managed to evade the advancing Wehrmacht and boarded a steamer, the Baron Nairn, at a Spanish port. Two days later, the Baron Nairn docked at Plymouth.

When they reached England, Tobin, Keough, and Mamedoff decided that they would join the RAF, having missed out on the Russo-Finnish War and the French Campaign. They were still looking for a fight, but U.S. Ambassador Joseph P. Kennedy, father of future president John F. Kennedy, had other ideas. Kennedy was a staunch isolationist, if not outright anti-British, and did not like the idea of American nationals joining the British air force.

The pilots got around Ambassador Kennedy, as well as the Neutrality Acts, with the help of a sympathetic member of Parliament. They were commissioned as pilot officers in the RAF and sent to an operational training unit in Cheshire, where they learned to fly Spitfires. From there, they were sent to 609 Squadron at Warmwell Aerodrome in Dorset, one of Fighter Command’s operational fighter bases against the Luftwaffe’s air fleets.

The three new squadron members were well liked and attracted their share of curiosity. Tall Red Tobin, from the Wild West of California, was compared to a cowboy in the movies. Andy Mamedoff was crazy about gambling and would bet on just about anything. Shorty Keough, who had made over 400 parachute jumps at air shows and state fairs in the 1930s, was just 4 feet, 10 inches tall. He needed two cushions to see over the top of a Spitfire’s instrument panel.

The other members of 609 Squadron thought the three Yanks were bigger than life. Much of this impression was based on their colorful personalities, but some of it was because of inflated flight histories. Red Tobin increased his flight time from 200 hours to 5,000 hours, but the squadron leader, Horace “George” Darley, refused to be impressed and would not allow the three Yanks to fly in combat until he was sure that they could take care of themselves.

Darley assigned the three new boys to ferrying jobs, flying Spitfires to another base and returning to Warmwell in a two-seat Miles Magister. Their only contact with air fighting came when they listened to the other pilots talk about their encounters with the Luftwaffe. In the summer of 1940, 609 Squadron was up to face the Luftwaffe every day. Red Tobin was on hand when Middle Wallop Aerodrome (known as Center Punch to the Yanks) came under attack. A Junkers Ju-88 bombed the base, destroying the hangar where Red was heading. The blast from the exploding bombs covered Red with dirt and made his ears ring from the concussion.

Finally, on August 16, Pilot Officers Tobin, Keough, and Mamedoff were pronounced operational and ready to fly combat operations. This was the third day of Reichsmarschall Hermann Göring’s Adlerangriff (Eagle Attack), the Luftwaffe’s maximum effort against the Royal Air Force and its communications network.

It turned out to be a frustrating day for Tobin. He and the rest of 609 Squadron were sent up to intercept an attack on Middle Wallop by German medium bombers escorted by fighters. Red fired at a twin-engine Messerschmitt Me-110, but it got away from him in spite of the fact that he emptied his .303 Browning machine guns on it. He fired 2,000 rounds of .303 ammunition, burned 80 gallons of gasoline, and did not accomplish one thing.

To make matters even worse, the bombing attack on Middle Wallop had not been stopped. More buildings had been blown up, the runway had been cratered by bombs, and the station’s telephone cables had been destroyed. Tobin had not come all the way from California for this.

Andy Mamedoff’s first action came on August 24, which 609 Squadron’s historian called “the Luftwaffe’s most destructive day in the whole Battle of Britain.” On this day, the German air force launched massive attacks against airfields throughout southern and southeastern England.

Mamedoff’s first day against the Luftwaffe was even less encouraging than Tobin’s. He did not shoot down any German aircraft either, and he was very nearly killed in his first air action. His Spitfire was destroyed by an Me-109, although he received only a minor injury and managed to nurse it back to base.

A 20mm cannon shell had gone right through the length of the fuselage. According to the damage report, the shell “entered the tail of the aircraft, went straight up the fuselage, through the wireless set, [and] just pierced the armour plating” behind the pilot’s seat, where it came to rest. Mamedoff had a bruised back to show for his first encounter with a Messerschmitt, but nothing worse. His Spitfire was a write-off.

The Yanks had come to England looking for a fight, and they certainly found what they were looking for. In August and September 1940, the Luftwaffe turned its full fury against Fighter Command, which was all that was stopping the Wehrmacht from invading England. Nearly every day from August 24 to September 6, the German air fleets inflicted heavy losses against the RAF fighter units and their pilots. The American volunteers saw their share of the fighting.

On the day following Andy Mamedoff’s brush with disaster, squadron mate Red Tobin shot down his first enemy aircraft and had a close call with disaster himself. He spotted an Me-110 at 19,000 feet and pushed his Spitfire’s engine to full throttle until he was within firing distance. When the twin-engine fighter filled the gunsight, Tobin pressed the firing button. Through the sight, he could see machine-gun strikes all along the length of the German fighter. The Me-110 reared up almost vertically. It then stalled out and plunged to earth, out of control.

Shortly after shooting down his first enemy aircraft, another Me-110 presented itself. For the second time, Tobin pushed the throttle full forward and closed for the attack. When he was within range, about 100 yards away, he held his gunsight on the enemy’s engine and pressed the firing button.

The Messerschmitt took many hits and began to lose altitude. Tobin dove after him. When the Messerschmitt leveled off, Tobin pulled back sharply on his control column to stay with the fighter—too sharply. G forces pulled the blood from his brain, and Tobin blacked out “colder than a clam,” to use his own description. His Spitfire stalled and spun out of control. When he woke up, Tobin was only 1,000 feet above the Channel.

Although Tobin came close to shooting down the second Messerschmitt, he did not complain. He knew that he might have splattered himself all over the English Channel. When he returned to base, he expected to get a severe reprimand from Squadron Leader Darley. Instead, Darley and everyone else in 609 Squadron were very glad to see Tobin. They had watched him spinning toward the Channel and thought he had crashed.

Tobin was in the air nearly every day from late August to mid-September, which saw some of the hardest fighting of the battle. The climax came on September 15, when hundreds of Spitfires and Hurricanes, almost 200 over London alone, intercepted roughly 200 German bombers and over 400 fighters. The resulting engagement has been referred to as the greatest air battle of all time and has been celebrated in Britain ever since as Battle of Britain Day.

On the 15th, Tobin’s day began before dawn when he was rudely awakened by a squadron mate. He was annoyed at having his sleep interrupted and wanted to know why the hell he should get out of bed when it was not even daylight. “I’m not quite sure, old boy,” came the reply. “They say there’s an invasion on or something.” Tobin was more impressed by the tone of the reply than by the news itself.

Tobin and the rest of 609 Squadron were not scrambled until later in the morning, when they were sent over London to intercept an incoming raid. He could see about 100 German aircraft approaching from the south, about 50 Me-109s above, 25 Dorniers below, and another group of 25 bombers in the distance.

As junior man in his flight, Tobin was “tailend Charlie” again, weaving to protect the tails of the flight leader and his wingman. When his section was preparing to drop on the Dorniers below, Tobin heard his leader call, “Okay, Charlie, come on in.” Before he joined up, Tobin took one last look around and saw three yellow-nosed Me-109s closing in from behind.

He screamed into the microphone, “Danger, red section! Danger! Danger! Danger! Danger!” and throttled back to put his Spitfire into a 360-degree turn. The German pilots were not able to slow down from their dive and shot past Tobin. He fired at the last Messerschmitt that went past and saw smoke trail from it as all three of the fighters disappeared.

By this time, Tobin was all alone, and his height was down to about 8,000 feet. He began climbing again. When he reached 10,000 feet, he saw a single Dornier Do-215 bomber. The German pilot saw Tobin at about the same time and headed for a cloud bank. Tobin dove after the bomber, trying to cut it off before it could reach safety.

Tobin closed with the bomber before it could get to the cover of the cloud bank and pressed the firing button. The Dornier’s port aileron instantly became perforated with bullet holes, and the port engine began to smoke. “I followed it down and saw a Dornier 215 make a crash landing two or three miles east of Biggin Hill,” Tobin said. “Three of the crew got out and sat on the wing.”

Pilot Officer Tobin had another confirmed kill to his credit, as well as another Me-109 damaged. Also, he remembered not to pull the control stick too sharply and did not knock himself out with excessive G forces. Along with Shorty Keough and Andy Mamedoff, he was learning.

The three Yanks of 609 Squadron accounted for three enemy aircraft destroyed during the Battle of Britain, along with many more damaged or probables. Red Tobin had two; Keough and Mamedoff were each credited with a half kill. Shorty Keough’s half-victory also came on September 15, and was also a Do-215.

The Battle of Britain did not end on September 15. The air battle between the RAF and the Luftwaffe went on until the last day of October. Some of the fighting of early autumn was as brutal as the battles of August and September. On October 29, for instance, the RAF lost 18 aircraft and the Luftwaffe had 31 planes shot down.

However, the Luftwaffe’s losses of September 15, originally given at 185 aircraft but later reduced to either 60, 56, or 50, depending on which source is consulted, persuaded Hitler and his High Command to cancel the invasion of England. Not many people in England knew it at the time, but Britain was safe from Hitler and his Wehrmacht after the 15th.

Four days later, Red Tobin, Andy Mamedoff, and Shorty Keough were posted to Church Fenton, in Yorkshire, to join Number 71 (Eagle) Squadron, the first of the RAF’s all-American fighter squadrons. Air Force records list them as the three original Eagles, the first to join the new squadron. As a matter of fact, when they arrived at Church Fenton, the three Yanks found that they were the only members of the squadron. There were no other pilots, no commanding officer, and no planes.

Originally, there had been plans to turn 609 Squadron into a mostly, though not totally, American unit. When Pilot Officer Chesley “Pete” Peterson, a Mormon from Utah, was posted to his first assignment, he was sent to 609 Squadron to join the other three Yanks, but when 71 Squadron was formed, his orders were changed. He was posted to the new Eagle Squadron at Church Fenton.

During their time with 609, Keough, Tobin, and Mamedoff learned a number of tricks of the fighter pilot’s trade—subtle things that were not taught in operational training school, such as conserving ammunition and getting as close as possible to the enemy before firing. They would now try to pass these bits of information along to the newly arrived Eagles. If their fellow countrymen hoped to survive against the Luftwaffe, they were going to need all the help they could get.

In most accounts of the Battle of Britain, the American volunteers have been treated either as squadron mascots or as some sort of publicity gimmick, but they played a serious role in the decisive air battles of the summer of 1940.

No one can say for certain how many Americans flew with RAF fighter squadrons. The Neutrality Acts prevented most of them from declaring their true nationality. There were at least 12, enough to form a complete RAF squadron, and probably more. Also, no one can say for certain how many aircraft they destroyed. The count comes to at least 15, enough to form a complete Luftwaffe squadron with several left over.

Part of the reason the Yanks received so little attention from British historians is because so many of them disguised themselves as either Canadian or Commonwealth pilots. Another reason is because British writers are reluctant to acknowledge the fact that Americans took part in a phase of the war that was almost entirely British—British pilots in legendary British fighters operating from British bases. Also, because the United States came to dominate the war later on, writers of RAF histories do not like to share the Battle of Britain, the high point of Britain’s year and a half alone, with Americans. Call it historic protectionism.n

David A. Johnson, who contributed an article to the first issue of WWII History, is currently working on his eighth book.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments