By Jon Diamond

Admiral Isoruku Yamamoto was not the only gambler in Imperial Japan’s military hierarchy. Lt. Gen. Tomoyuki Yamashita, appointed commander of the Imperial Japanese Army’s (IJA) 25th Army on November 2, 1941, to lead the invasion of Malaya and Singapore, also took risks to capture the prized British territory in less than 100 days after his invasion commenced on December 8.

Yamashita’s rationale was to defeat the British and Commonwealth forces there before significant enemy reinforcements could arrive. Yamashita was also aware of his perilous political position in Tokyo and how only a quick, decisive victory could protect him from demotion or worse. When the IJA command offered him five divisions, he stated that he would need only three. With a deadline and a long supply line with limited opportunity for replenishment, the fewer troops deployed to achieve conquest the better.

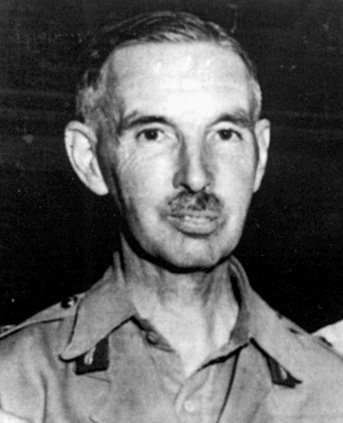

Yamashita’s counterpart, Lt. Gen. Arthur E. Percival, knew how weak Malaya and Singapore’s defenses were, having correctly predicted in 1937 the Japanese strategy for seizing Malaya by storming ashore well north on the Kra Peninsula at the Thai ports of Singora and Patani. A rapid drive through northern Malaya and then down the west coast’s main trunk road would culminate in an amphibious assault on Singapore across the narrow Straits of Johore rather than a full-scale invasion of the island’s fortified southern shore.

Percival, among others, was bluffing that the Royal Air Force (RAF) and Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF), with their limited strength concentrated on northern Malayan airfields, would smash the invasion. There were about 80,000 British Army troops in Malaya; however, less than half were first rate. The stage was set for two competing commanders to use their limited forces and military bluff, the outcome of which would be Britain’s largest military disaster since Cornwallis’s capitulation at Yorktown in 1781. Poor planning and leadership of British defenses coupled with an under-equipped garrison and Yamashita’s military deception during the campaign’s climax precipitated Singapore’s surrender on February 15, 1942.

The Malay Peninsula measures approximately 450 miles north to south and has numerous east-west running rivers that intersect two coastal plains filled with dense, impenetrable jungle and large areas of swamp. The Japanese wanted to seize Malaya because it produced approximately 40 percent of the world’s rubber and 58 percent of its tin. The peninsula’s western shoreline, flanked by coastal plain, has many mangrove swamps, while the eastern coast has sandy beaches suitable for amphibious landings. On the western plain is a major motor road trunk, which though built for commerce would afford an invading army a much easier trek down the peninsula to Singapore.

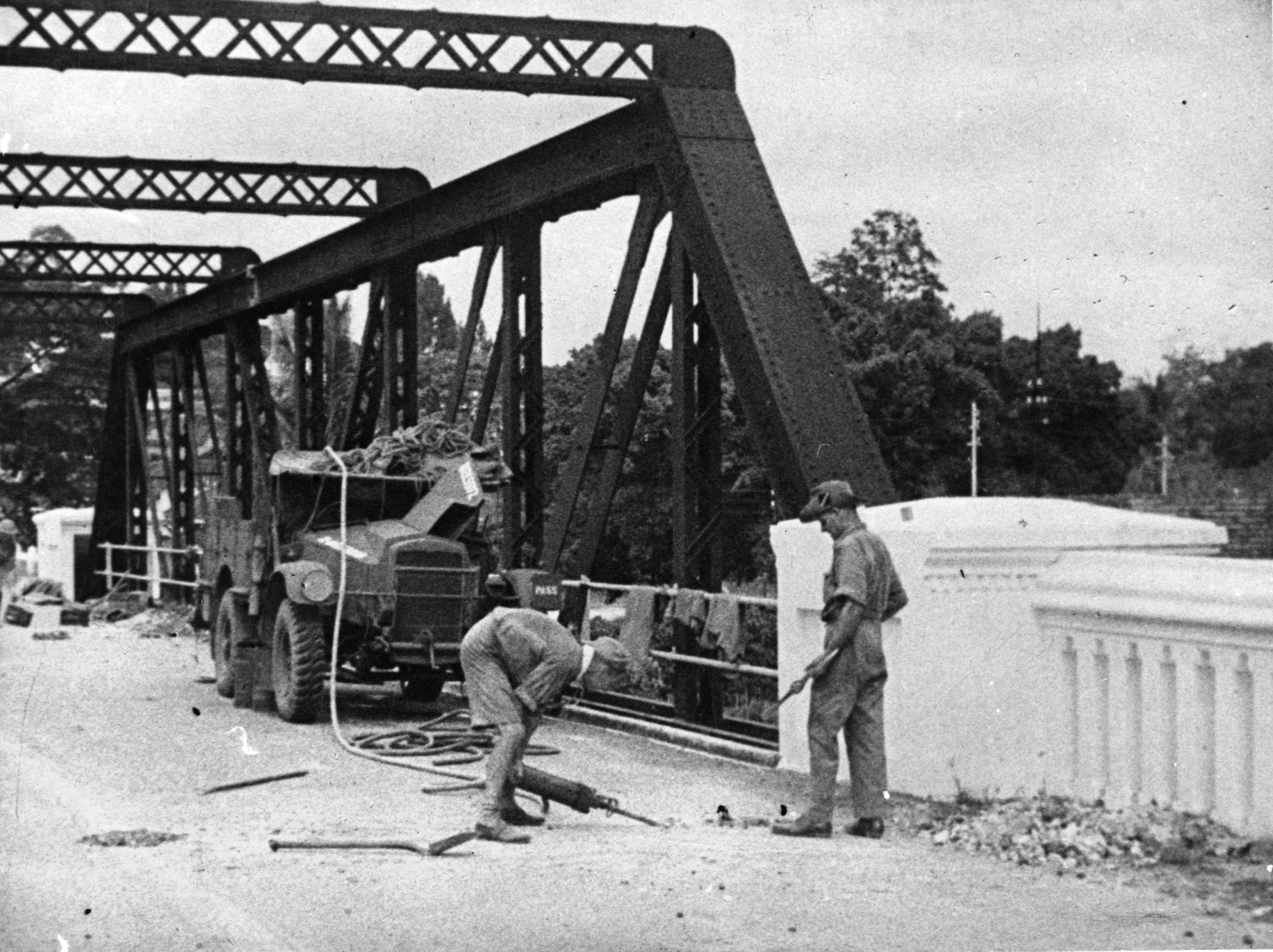

The IJA planners noted that there were about 250 bridges along the main trunk road between Singapore and the Thai border. Japanese logisticians, principally Colonel Masanobu Tsuji, realized that the longer it took the Japanese to repair destroyed bridges the more time was afforded to British and Commonwealth troops to erect new defenses, especially in southern Malaya’s Johore Province and on Singapore Island. Thus, an entire engineer regiment for bridge reconstruction would accompany each of the three divisions in Yamashita’s army.

At the tip of the Malay Peninsula across the Straits of Johore lies Singapore Island, Britain’s defensive epicenter in the Far East. Singapore is a wet, low-lying island of about 240 square miles located just north of the equator. It extends some 27 miles from east to west and 13 miles north to south with a coastline fringed by mangrove swamps, creeks, and small rivers. The Straits of Johore varies in width from 600 to 5,000 yards, and near the narrowest point the British constructed a causeway. Most roads led to Singapore City, located on the southeastern shore of the island, where the approximately 500,000 inhabitants of various ethnicities dwelled. Except for scattered towns and settlements, the rest of the island was rubber plantation and jungle.

The British high command on Singapore Island, believing their position impregnable, had strongly fortified only the southern and eastern coasts of the island against seaborne assault with large-caliber naval guns. In addition to the two 15-inch naval guns firing armorpiercing shells from the Buona Vista and Johore Batteries, Singapore also possessed two batteries of 9.2-inch guns, the Connaught Battery on Pulau Blankang Mati, south of Keppel Harbor, and the Tekong Besar Battery on the island of that name northeast of Singapore Island. There were nine batteries of 6-inch guns scattered across the island; however, no naval gun batteries were situated along the northern coast of Singapore Island despite the expansive naval base located there at Sembawang.

During their autumn 1941 planning, the Japanese were less concerned about the British naval guns than the RAF and RAAF aircraft stationed on Singapore and at multiple airfields in northern Malaya, which could interdict Japanese lines of communications and interfere with scheduled IJA offensives in Sumatra and Java. These RAF and RAAF airfields had to be captured before any subsequent operations could be mounted. This approach was taken despite the reports from Japanese sympathizers that the British air defenses were a paper tiger with only about 30 percent of almost 600 planes actually available. Antiaircraft defenses to protect the airfields were almost nonexistent until the outbreak of hostilities. As December 1941 loomed, the British Army in Malaya still was short two of its requested six infantry divisions, an armored regiment, and additional antiaircraft batteries.

Field Marshal Archibald P. Wavell, commander in chief of British forces in India, noted before Pacific hostilities erupted, “My impressions were that the whole atmosphere in Singapore was completely unwarlike, that they did not expect a Japanese attack and were very far from being keyed up to a war pitch.”

This indifferent view was expressed by the local British military service commanders despite the vast Singapore Naval Base, which had been built after years of vociferous debate in Whitehall. The naval base was finally opened in 1938 and cost more than 60 million pounds sterling. Its principal purpose was to serve as a deterrent to Japanese aggression against Britain’s Far East colonies. However, the base did not possess its own battle fleet.

In the event of war, Singapore’s commanders envisioned that the Royal Navy would sail through the Suez Canal, across the Indian Ocean, and through the Malacca Strait to Singapore Island. Percival and General Sir William Dobbie, commander in Malaya in the late 1930s, postulated that a British fleet could not arrive in less than 70 days. If Japan attacked Malaya and Singapore, it would be left to the RAF and RAAF to protect the naval base at Sembawang, while the British Army and its Commonwealth contingents were to protect the airfields on the Malay Peninsula.

The RAF and RAAF possessed too few frontline aircraft to engage the far superior Japanese planes. Also, the British and Commonwealth troops in Malaya were understrength, poorly trained for jungle warfare, and without a single tank. The military minds in London argued that tanks were unsuitable for jungle warfare. Prime Minister Winston Churchill had committed Britain’s armored forces to North Africa and Greece rather than Singapore.

In May 1941, a rancorous debate developed between the prime minister and his chief of the Imperial General Staff (CIGS), General Sir John Dill, who favored reinforcing Singapore with some armor. After Operation Barbarossa started the following month, Churchill promised his new ally, the Soviet Union, Britain’s older model infantry tanks, which would have been equal or superior to the Japanese armor that was to land on the Malay Peninsula.

Churchill committed only a token naval presence, Force Z, to Singapore in the fall of 1941, comprising the modern battleship HMS Prince of Wales, the old battlecruiser HMS Repulse, and four vintage destroyers under the command of Admiral Sir Tom Phillips. There was no accompanying air cover against what would soon be waves of Japan’s Saigon-based naval bombers that would sink the two British capital ships in the Gulf of Siam on December 10, 1941.

Incredibly, the prewar defense of northern Malaya was left in the hands of the Federated Malay States Volunteers. A newly arrived Indian brigade group was held as a reserve for the defense of Johore Province. Singapore Island was entrusted to five regular battalions, two volunteer battalions, two coastal artillery regiments, three antiaircraft regiments, and four engineer fortress companies. Six air force squadrons had fewer than 100 aircraft, including such venerable models as the Vicker Vildebeest biplane torpedo bomber, Hawker Harts, and Audax biplanes. Some of the other service chiefs had held erroneous beliefs that their meager resources and near obsolete equipment would be sufficient to combat a battle-hardened Japanese war machine, which was honed to a sharp edge by the conflict on the Chinese mainland. Air Chief Marshal (ACM) Sir Robert Brooke-Popham, commander in chief Far East, remarked incredulously, “We can get on alright with [Brewster] Buffaloes out here … let England have the Super-Spitfires and Hyper-Hurricanes.”

The Brewster F2A Buffalo fighter was inferior in virtually every respect to the Mitsubishi Zero but was still thought to be capable of defeating Japanese aircraft.

In the absence of Allied tanks, the Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders had instead been issued Bren carriers mounting the .55-inch Boys antitank rifle along with Lanchester and Marmon-Herrington armored cars, the former of which was obsolete and the latter rushed into production. The Lanchesters were built in 1927 and were equipped with two 7.7mm Vickers machine guns and a Boys antitank rifle. The South African-made Marmon-Herrington vehicle, built in 1938, carried the same armament. The Boys antitank rifle had limited effect on Japanese medium tanks, while the Japanese 37mm tank gun was adequate against the armored cars, which usually had only 12mm of armor protection.

Upon his arrival in Malaya in April 1941, Percival deployed his three British and Indian Army divisions and three separate brigades in defensive positions near the airfields. The 2nd Battalion, Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders, under Lt. Col. Ian Stewart, had arrived in August 1939 and under Stewart’s training regimen became the best trained British jungle fighters in Malaya.

The III Indian Corps, commanded by General Sir Lewis Heath, was charged with the defense of northern Malaya. Its 11th Indian Division was deployed near the Thailand-Malayan border, under the command of Maj. Gen. David M. Murray-Lyon, while the 9th Indian Division was situated along the east coast of the peninsula. Construction of defenses was stalled because of bureaucratic issues. Apart from a few regular British, Australian, and Indian Army battalions, the remaining troops were of low quality.

South of III Corps’ area, the 8th Australian Division defended Johore Province at the southern tip of the peninsula. An additional two infantry brigades were charged with the defense of Singapore Island proper, and a brigade remained in reserve. Because he had widely dispersed his divisions and brigades, Percival was unable to concentrate his combat power at any one point until the Japanese had already overrun the peninsula.

At the command level, a vacuum of leadership developed at a crucial stage. Air Chief Marshal Brooke-Popham was replaced by Lt. Gen. Henry Pownall in November 1941. Brooke-Popham did not arrive in Singapore until December 27. Field Marshal Wavell was then appointed to the American-British-Dutch-Australian (ABDA) command. One of Churchill’s political allies, Duff Cooper, was appointed chairman of the Far East War Council. He had a fractious relationship with the local military leaders and departed for England after Wavell assumed the ABDA command in early January. Thus, Percival’s chain of command was initially more illusory than extant.

At the subordinate level, Percival had difficulties with both Heath and Maj. Gen. H. Gordon Bennett, commanding the Australian troops in Malaya and Singapore. Heath was actually senior to Percival, but after fighting commenced in northern Malaya, Percival lost confidence the III Corps Indian commander. However, Percival chose not to relieve Heath. Bennett was a bitter, outspoken subordinate prejudiced against the British military hierarchy. Like all Commonwealth commanding officers, Bennett had the option to discuss orders from Percival with the Australian government if he disagreed with them. Although Percival had the opportunity to sack Bennett as well, he allowed him to continue commanding the Australian contingent.

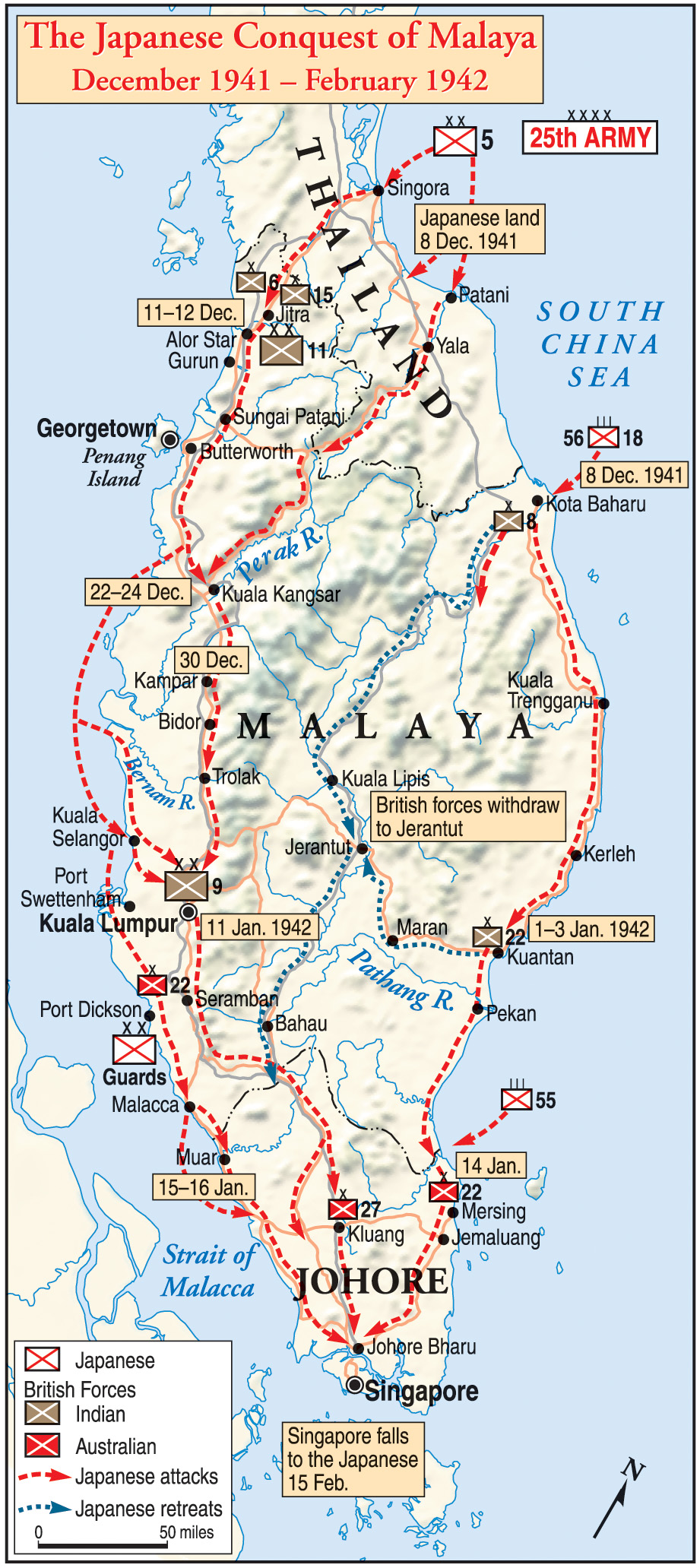

Yamashita’s 25th Japanese Army was composed of three crack infantry divisions, the 5th, 18th, and Imperial Guards, which was to concentrate on the RAF and RAAF airfields in northern Malaya during the initial stages. The 5th Division with a tank regiment’s support would land at Singora and Patani, both harbors with beaches on Thailand’s east coast just north of the Malaya border, and then rapidly drive south into western Malaya to capture the Kedah Province airfields along the northwestern Malayan coast. After crossing the Perak River, the 5th Division was to continue southward and capture Kuala Lumpur, the capital of Malaya’s Federated States.

The 18th Division’s 56th Regiment, also known as Takumi Force (after its commander Maj. Gen. Hiroshi Takumi), was to land on the northeastern Malay coast near the key airfield of Kota Bahru, just south of the Thai border, capturing nearby airfields. The 56th Regiment was then to trek southward along Malaya’s eastern coast to Kuantan and capture its airfield. Another regiment from the 18th Division was to seize British Borneo while the third regiment landed at Singora-Patani as a reserve.

The Imperial Guards Division would land later at Singora or another port to be selected and follow the 5th Division into Malaya to become part of the reserve after assisting in the seizure of Thailand and the opening of the invasion of Burma. Once the advance south was proceeding, these two divisions would occupy the main trunk road down Malaya’s west coast and head southward.

Two of the three division commanders had good relationships with Yamashita and possessed vast experience in opposed landings during the Sino-Japanese War. They were Lt. Gen. Takuro Matsui, commander of the 5th Division, and Lt. Gen. Renya Mutaguchi, commander of the elite 18th, or Chrysanthemum, Division. Lt. Gen. Takuma Nishimura, commander of the Guards Division, was an old enemy of Yamashita. Two regiments of heavy field artillery and the III Tank Brigade with more than 230 light and medium tanks supported the infantry divisions.

The total strength of the 25th Army was 80,000 men. Yamashita was also to be supported by the 3rd Air Division and the navy’s fleet air wing. The Japanese air presence was intended to first neutralize the threat of the RAF and RAAF in Malaya and then provide the necessary tactical air support against Commonwealth forces on the peninsula.

At 0200 on December 6, 1941, RAAF airmen flying a Lockheed Hudson bomber based at Kota Bahru alerted Brooke-Popham to Japanese convoys heading for Thailand’s east coast. Brooke-Popham was not going to start a war with Japan by setting early defensive measures codenamed Matador into motion by himself. In fact, both Whitehall and Churchill shared this same nonaggressive stance as well. Percival was also dithering about ordering Matador to commence. He was of the opinion that an encounter between the Japanese landing force and his 11th Indian Division would be a risky endeavor, especially if the Japanese landed tanks. Percival informed Brooke-Popham that he now considered Matador unsound.

At Singora and Patani, the 5th Division’s unopposed landings commenced on December 8 at 0400, just over an hour after the Pearl Harbor raid began. Japanese aircraft quickly occupied the airfields at Singora and Patani and destroyed 60 of the 100 British aircraft on the ground in northern Malaya by December 9, gaining total air domination by the end of the fourth day of the invasion.

Takumi Force was strongly opposed at Kota Bahru by the 8th Indian Infantry Brigade just a few hours later. At 0130, the invaders’ local ground commander, Colonel Yoshio Nasu, signaled Takumi, “Have succeeded in landing but there are many obstacles. Send second wave.” At 0200, RAF aircraft bombed the supporting convoy, scoring a hit on Takumi’s headquarters ship, Awajisan Maru, and leading the naval escort commander to suggest calling off the landing and heading out to sea away from the threat of aerial assault.

Takumi refused and continued the second wave’s landing despite the need to abandon the Awajisan Maru and heavy casualties inflicted by British machine-gun positions. With the surface fleet lending naval gunfire, the Japanese broke through the Indian brigade defending the coastline at bayonet point. By midnight, the airfield at Kota Bahru was firmly in Japanese hands.

Percival sent the 11th Indian Division to Jitra to defend the nearby airfield and preserve the vital link to both Thailand and Burma. However, this division had done little preparatory work on its defensive line until the evening of December 10. Because this division had squandered time awaiting Brooke-Popham’s decision on Matador, the Jitra line looked like a rundown construction site. The presence of airfields at Alor Star, 12 miles to the south, made this locale vitally important to both sides. At Jitra the west coast railway and road trunk came together and ran parallel for 50 miles until they separated at Butterworth and the ferry point for Penang Island.

The 5th Division was ordered to move west on Jitra from Singora and Patani. From the first, the Japanese Army had kept the British off balance in Malaya. Murray-Lyon, commanding the 11th Indian Division, had known that his chances of holding the incomplete Jitra line were slim. Mixed with the brigades of the 11th Indian Division were three regular British Army battalions from the Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders, the East Surreys and the Leicesters. They totaled over 2,000 men and comprised a fifth of the division’s infantry. However, despite being outnumbered more than two to one, the Japanese surged down the main roads on the western side of the peninsula on thousands of bicycles and in hundreds of abandoned British cars and trucks.

Because of Malaya’s intense heat, the bicycles’ tires blew out; however, the resourceful Japanese learned to ride down the paved motor road on the wheel rims. Metal to pavement sounded like approaching tanks, and the peninsula’s defenders, notably the inexperienced Indian troops who were terrified of armor, often broke for the rear.

At 0800 on December 11, advance elements of the 11th Indian Division, the Punjabis, were attacked by a Japanese armored reconnaissance unit supported by 10 light and medium tanks. After some of the Indian positions had become compromised, they repositioned themselves; however, while the men were moving their antitank guns and equipment in steady rain another tank assault with truck-borne infantry caught the rear of the column and wreaked havoc on it.

After the destruction of the Punjabis, the Japanese attacked the 2/1st Gurkhas and a battalion, the 2/9th Jats, of the 28th Brigade at 2030; however, stiff artillery and machine-gun fire broke the assault. The Japanese made another assault against the Indian center, which held out until a Japanese flank attack panicked the remnants of the 11th Indian Division. On December 11, Murray-Lyon asked his III Corps commander, General Heath, for permission to withdraw to a more suitable antitank barrier. After some vacillation, at 2200 he received orders to withdraw from Jitra 15 miles to the south. The hasty retreat was exploited by the Japanese, forcing the evacuation of Penang Island on December 16 and the abandonment of numerous barges, motor launches, and junks that would be used later by the Japanese for seaborne flank attacks farther south.

The fight at Jitra was disastrous for the British and Indian troops, with casualties running into the thousands coupled with losses of guns, vehicles, supplies, ammunition, and morale. Japanese casualties were light, and the morale of the victorious troops soared. The British lost the initiative after Jitra because there would not be enough time to adequately establish defensive positions in Johore Province and Singapore.

Now that all Allied opposition was crushed in northwest Malaya, Yamashita ordered his Takumi Detachment to deal with the 9th Indian Division on the east coast after landing reinforcements at Kota Bahru. Yamashita’s goal was to occupy Kuala Lumpur by mid-January and reach the Straits of Johore by January 31. A large part of Yamashita’s success in northwestern Malaya’s Kedah Province was attributable to the use of tanks. The main tank was the Type 97 Chi-Ha medium tank, which had a 57mm gun and two machine guns. The British, lacking armor, could only answer with their 2-pounder antitank guns if they were unlimbered and in ambush positions.

On December 16, most Europeans from Penang Island were evacuated to the west coast of Malaya. Penang Island, with its harbor located at Georgetown, had been viewed as a fortress by the British. It was another vital site that Yamashita’s 25th Army had to seize to keep his coastal flank free of Allied air or seaborne attack as he descended the western side of the peninsula in his drive toward Singapore. Another reason for the British desire to hold Penang Island was its underwater communication cables with both Ceylon and India, and thence to London and the War Cabinet.

Percival had a contingency plan to defend Penang Island, but it fell apart when the 11th Indian Division, which was to support the island’s garrison, was routed at Jitra. Also, the island’s garrison had been ferried to the mainland in an attempt to halt the Japanese advance. There were no first-rate troops left to defend Penang Island. Two companies from the Japanese 5th Division arrived unopposed in Georgetown at 1600 on December 19. Yamashita had captured the fortress of Penang Island without firing a shot.

The capture of Kota Bahru on December 8 was followed by a steady southward advance down the eastern coast of the Malay Peninsula, ultimately forcing the 9th Indian Division into Kuantan, halfway between Kota Bahru and Singapore, by the end of December. On December 23, Percival countered by allowing the 9th Indian Division to extract itself west of Kuantan to defend Kuala Lumpur. However, to achieve this the 11th Indian Division needed to occupy defensive positions in Kampar on December 27. The Japanese 5th Division attacked Kampar on December 30, but the 11th Indian Division held out against the usual Japanese flank attacks and infiltration. The Japanese response was to launch an amphibious westward turning movement, using the watercraft captured at Penang Island and the small boats brought overland from the Singora landing.

Again, the 11th Indian Division was without sufficient reserves to repel the Japanese landing. By January 2, 1942, Percival pulled the remnants of the division behind the Slim River. Pownall, who knew Percival from their British Expeditionary Force (BEF) days in France in 1940, wrote in his diary, “[Percival is] an uninspiring leader and rather gloomy. I hope it won’t mean that I have to relieve Percival…. But it might so happen.”

On January 7, during his visit to Singapore to inspect the defenses on the north side of the fortress island, Wavell, the new ABDA commander, found nothing erected nor any detailed plans made for resistance against a land invasion from across the Straits of Johore. The field marshal had also learned that only the 6- and 9.2-inch guns on Blankang Mati Island, south of Keppel Harbor on Singapore Island’s southern shore, could be turned to fire inland. However, these batteries were equipped with armor-piercing shells for ships rather than high-explosive shells to break up infantry/armor attacks.

Percival’s chief engineer, Ivan Simson, also badgered his commanding officer that there was a need to erect fixed defenses in Johore for the exhausted 11th Indian Division to retreat into, and time was running out to secure the northern shores of Singapore Island should evacuation of the peninsula become necessary. Ironically, the southern shore of the island bristled with defenses. Percival gave the lame excuse that erecting fixed northern shore defenses would weaken civilian morale while those in Johore would rob the 11th Indian Division of an offensive fighting spirit. A few days after his encounters with Wavell and Simson, Percival took their advice and directed his engineers to prepare a series of obstacles on the northern shore.

The British commanders on Malaya and Singapore Island could not have foreseen such a rapid advance by Yamashita’s three divisions. A captured British officer from the Royal Engineers had told Colonel Tsuji that he had expected the defenses in northern Malaya to hold out for substantially longer than the few weeks that they had and mentioned, “As the Japanese Army had not beaten the weak Chinese Army after four years’ fighting in China we did not consider it a very formidable enemy.”

The month of January brought further disasters for the British and Commonwealth troops defending the Malay states to the north. The Japanese crossed the Perak River unopposed and advanced in strength down the motor road trunk toward the Slim River, which flows in an east-west direction near Telok Anson. After some fighting in Telok Anson, in which the Japanese 4th Guards Regiment and the 5th Division’s 11th Infantry Regiment were landed by barge on January 1, British troops disengaged to the natural shelter of the Slim River. However, on January 2, the Japanese were making landings at Selangor and Port Swettenham, 70 miles behind the 11th Division in southern Perak Province.

On the eastern coast, the Allied 9th Division was retreating into central Malaya from Kuantan. General Heath was forced to abandon the airfield at Kuantan. Percival was already convinced that eventually III Corps would have to execute a retreat in stages into northern Johore, where the final stand on the mainland would be made. Kuala Lumpur would also eventually be abandoned.

The Japanese began their attack on the Slim River line on January 5 and were initially beaten off by two battalions of the 12th Indian Brigade, resulting in heavy casualties. However, on the night of January 7, Japanese tanks attacked down the motor trunk road and cleared the Indian roadblocks before any Allied antitank guns could be employed, resulting in the retreat of the 12th Indian Brigade. The attack across the Slim River continued a few miles to the south, where the Japanese engaged the 28th Indian Brigade. Allied Gurkhas and Punjabis were badly mauled, and the Japanese soon controlled the Slim River road bridge with all of the 11th Indian Division’s motor transport trapped on the northern side. Casualties among the 12th and 28th Indian Brigades were extensive. After the Japanese captured all of the division’s artillery, including 16 25-pounder guns and seven 2-pounder antitank guns, only about 1,000 British and Indian soldiers from the 11th Indian Division were able to escape south by foot.

According to the official British history of the war in the Far East, “The action at the Slim River was a major disaster. It resulted in the early abandonment of Central Malaya and gravely prejudiced reinforcing formations, then on their way to Singapore, to arm and prepare for battle…. The immediate causes of the disaster were the failure to make full use of the anti-tank weapons available.”

British commanders confessed that they had no prior experience fighting tanks at night or in using field artillery in an antitank role. In addition, the motor road bridge across the Slim River was not demolished by the British, enabling the Japanese advance to continue unimpeded.

To compound the operational dysfunction at Percival’s headquarters, Wavell arrived on January 7 and accepted General Bennett’s plans for the defense of Johore as a “done deal,” which was the direct opposite of Percival’s plan that the Australians would defend the east coast of Johore Province while Heath’s III Corps held the west coast. Pownall noted in his diary that Wavell was “not at all happy about Percival, who has the knowledge but not the personality to carry through a tough fight.”

After the crossing of the Slim River, Wavell drove north to find III Corps disorganized and the 11th Indian Division completely shattered. Wavell, too, recognized that the disaster at the Slim River necessitated the shifting of the entire British line back to the southern tip of the Malay Peninsula and ordered a general withdrawal of the Indian troops of almost 150 miles southeast to Johore Province for reorganization. There would be nothing between the victorious Japanese and Kuala Lumpur.

A new line was formed with the 9th Indian Division and the rested 8th Australian Division, the latter already positioned in Johore, to hold along the Muar River on the western coast, while the remnants of III Corps defended the eastern coast at Mersing. General Bennett’s Australians would be entrusted, in large part, to make the final attempt to stop Yamashita’s onslaught, while the battle-weary 9th Division would contribute to the line’s defense. The remnants of the 11th Indian Division would refit in Johore.

Despite the visit by Wavell and the expectation that the British 18th Division would arrive to reinforce the Australians, giving Bennett some offensive punch, Yamashita committed troops of the Guards Division, which reached Ipoh. He was also bringing more of Mutaguchi’s 18th Division down to Johore by road. Wavell, on January 9, discussed his plan with Bennett at Johore Bahru that a decisive battle should be fought on the northwest frontier of Johore near the mouth of the Muar River, using the Australian 8th Division (less the 22nd Brigade) that had been stationed in Mersing and the 45th Indian Brigade as the main Allied force. The 9th Indian Division and the 45th Indian Brigade would come under Bennett’s command as Westforce while Heath’s III Corps would withdraw into southern Johore Province.

The Australian 22nd Brigade would remain in Mersing but rejoin the Australian 8th Division on the Muar for an Allied counterattack against Yamashita’s forces on the peninsula. The 22nd Brigade would join Bennett’s forces after it was relieved by reinforcements from Singapore Island, which would not be before the middle of February. Wavell and Bennett’s plan depended on holding the Japanese in northern Johore Province until reinforcements arrived. Already, the Japanese 5th Division had entered Kuala Lumpur on January 11, capturing copious amounts of supplies and equipment.

Initially, Bennett’s fresh Australian troops gained some success against the Japanese, principally by ambushing them on the Muar-Bakri road west of Gemas on January 14-15; however, the Japanese crossed the Muar River without much opposition since Bennett believed that the bulk of Japanese forces would attack down the trunk road in the vicinity of Gemas. At the Muar River, the 4th Japanese Guards Regiment annihilated the Indian companies of the Rajputana Rifles, which had been poorly positioned on the north side of a river that did not have a bridge to retreat over.

At 0200 on January 16, the Japanese crossed the Muar River in force a few miles upstream of the Indians and established a roadblock. Yamashita had just turned Bennett’s left flank, and when the 45th Indian Brigade began its withdrawal Westforce was in danger of being surrounded. Wavell, having left Singapore for Java on January 10, had always regretted that he did not send the 22nd Brigade to Bennett to stiffen up Westforce prior to being replaced at Mersing by reinforcements. It was clear that even Bennett’s Australians could not stem the Japanese tide as it methodically kept demolishing each new static line of defense that the Commonwealth forces established, even though they were inflicting casualties on the Japanese.

Singapore fell to the invaders in February 1942.

On the afternoon of January 18, the British knew that the entire Imperial Guards Division was in the Muar area while the Japanese 5th Division was on the main road heading south. Despite a trickle of reinforcements from Singapore that Percival had dispatched to the peninsula, Bennett knew that unless the Westforce retreated his main force would be destroyed. Bennett’s command was forced to withdraw from northwest Johore Province on the evening of January 19 over the one narrow bridge spanning a deep gorge of the Segamat River. In fact, the depleted 45th Indian Brigade had held up the Imperial Guards long enough to save Westforce from encirclement. After the Battle of the Muar, the 45th Indian Brigade ceased to exist.

On January 19, Wavell learned that there was no formalized plan to withdraw to Singapore Island. Wavell cabled Percival, “You must think out the problem of how to withdraw from the mainland … and how to prolong resistance on the island.”

Percival, in response to Wavell’s cables, planned for his Malayan forces to retreat in three columns and the establishment of a bridgehead covering the passage through Johore Bahru. The following day, January 20, Wavell met with Percival on Singapore Island to plan its defense since the outcome of the battle on the mainland appeared to be a foregone conclusion. To his dislike, Wavell found that little had been done to strengthen the island’s northern defenses and outlined some of his thoughts on augmenting defensive capabilities.

The Japanese launched three divisions in southern Johore against the British line, necessitating Percival on January 24 to issue orders for the withdrawal from the southern Malay Peninsula to Singapore Island should it become necessary. On January 28, Percival informed his division commanders that the evacuation should be carried out on the night of January 30-31 to form another defensive line on Singapore Island across the two to three-kilometer wide Straits of Johore. By dawn on January 31, British forces were over and preparations moved forward to destroy the causeway across the Straits of Johore. The straits were scarcely four feet deep at low tide where the causeway once stood.

Percival assumed operational control of all troops on Singapore Island, and despite fresh reinforcements, including the 44th Indian Infantry Brigade, the British 18th Division, and approximately 2,000 Australians, the situation remained bleak since they were mostly untrained and not acclimated to the equatorial conditions. Although Percival commanded 85,000 troops to defend a land mass of 220 square miles, some 15,000 of them were administrative and noncombatant forces. Also, many units were lacking both adequate weapons and an appropriate esprit de corps to combat the Japanese.

Percival’s staff officers had clouded their commander’s military thinking by estimating that he would be fighting against 65,000 Japanese troops on the other side of the Straits of Johore. The Japanese had only 30,000 combat troops. Also, due to less than optimal intelligence gathering, the Japanese had planned to engage only 30,000 British and Commonwealth troops. Numerically, the defenders had more than enough strength on the island to repel the invasion. In Percival’s favor, Singapore had ample provisions of food and was well stocked with ammunition for its artillery batteries and small arms.

Percival now failed to take the counsel of both his subordinate commanders and Wavell. In a tactical disagreement, Percival opted for an all-around perimeter defense of the island’s beaches, whereas Wavell recommended that he concentrate his forces against the likely Japanese landing sites in the northwest and northeast corners of Singapore Island, while also massing some reserves inland for a strong counterattack to throw the invaders back into the Straits of Johore.

Percival divided the 27-by-13-mile island into three sectors with the Australian 22nd and 27th Brigades in the west, the 28th Indian (Gurkha) Brigade; the British 18th Division’s 53rd, 54th, and 55th Brigades in the northern sector; and a southern zone to be held by the newly arrived 44th Indian Brigade along with the Singapore Straits Volunteer Force and the 1st and 2nd Malay Brigades, constituting the reserve to the west and east of Singapore City.

Before the war, the Japanese had studied the problem of attacking Singapore Island. They decided that the most favorable line of attack would be to cross the narrowest portion of the Johore Strait in the northwest. The southern coast of Johore Province opposite this landing area offered both roads and swamps to amass the necessary forces in comparative secrecy. Yamashita’s intelligence reports indicated that the British expected the main attack to be hurled against the naval base at Sembawang to the northeast.

Yamashita decided to make his main thrust with the 18th and 5th Divisions against the northwest coast of the island, away from the three brigades of the newly arrived British 18th Division positioned near the naval base. Also, Yamashita would make a diversionary attack with the Imperial Guards Division well to the east to deceive the British about the major attack site. Then, he would deploy the main part of this division to the immediate west of the causeway after the main attack of the Japanese 18th and 5th Divisions had been successfully delivered.

On January 31, after the Allies abandoned the Malay Peninsula, Yamashita held a conference with his staff officers and told them that it would take four days to adequately reconnoiter for optimal crossing sites at the Straits of Johore. Japanese engineers also worked to repair the destroyed causeway. True to his schedule, on February 4, Yamashita’s reconnaissance was complete. He gathered his division commanders at midday on February 6 to distribute their orders. During the days preceding the Japanese attack across the straits, Yamashita brought up his artillery, ammunition, and supplies using captured railway stock and trucks. He also hid hundreds of folding boats and landing craft for the eventual crossing in the swampy areas about a mile from the straits.

The Imperial Guards Division began its demonstration attack as planned on the night of February 7. Twenty noisy motor launches containing 400 Guardsmen landed on Ubin Island in the straits overlooking the Changi fortress and airfield to be easily detected by the British troops garrisoning the naval base. On the morning of February 8, Yamashita’s artillery began its bombardment of the Changi fortress as the British, having fallen for the decoy attack, rushed reinforcements to the northeast corner of the island.

After the sun had set that day, Yamashita’s 5th and 18th Divisions carried their folding boats to the straits’ edge. As these troops reached the water, a massive artillery bombardment commenced against the naval base to destroy its oil tanks, depriving the British of the option of setting the straits afire with dumped gasoline. Then Yamashita’s artillerymen turned their attention to Percival’s machine-gun nests, infantry trenches, and barbed wire below the causeway at the northwest corner of the island.

At 2230, a force of 4,000 men in a flotilla of more than 300 assorted boats crossed the straits toward the awaiting 2,500 men of the 22nd Australian Brigade. Within minutes of their crossing, elements of the 5th Division were ashore facing heavy Australian machine-gun fire, while other Japanese troops landed in a mangrove swamp that was less defended. In some areas, the Japanese had to make three attempts before securing a beachhead on the island. After midnight, the Australians were being attacked from the rear as well as the front. The Australian brigades were unable to hold back the main Japanese invasion.

By 0300 on February 9, the entire 22nd Brigade was ordered back to a prepared position. At dawn, Japanese tanks with fresh 5th and 18th Division infantry—totaling roughly 15,000 men—arrived in waves. Once Yamashita observed that his invading force had reached the Tengah airfield, well inland on the island’s western side, he crossed the straits himself. His troops were no farther than 10 air miles from Singapore City in the southeastern corner of the island.

Yamashita’s assault on Singapore Island was executed with surgical precision and efficiency. Also, on February 9 the main elements of the Imperial Guards crossed the straits immediately west of the causeway, deploying through Johore Bahru town to confront the Australian 27th Brigade. After landing, the Imperial Guards Division was to swing east toward Sungei Seletar and then south between Singapore City and Changi to prevent the British from withdrawing into the Changi area. The Japanese 14th Tank Regiment was attached to this division.

On February 9, Wavell, flew from Java to Singapore. The ABDA commander railed at both Percival and Bennett for allowing the Japanese to establish a firm beachhead so easily. He issued an order for an immediate counterattack and reminded the British and Commonwealth officers, “It is certain that our troops on Singapore Island greatly outnumber any Japanese that have crossed the Straits. We must defeat them. Our whole fighting reputation is at stake and the honour of the British Empire. The Americans have held out on the Bataan Peninsula against far greater odds, the Russians are turning back the picked strength of the Germans, the Chinese with almost complete lack of modern equipment have held the Japanese for four and a half years. It will be disgraceful if we yield our boasted fortress of Singapore to inferior forces [numerically].”

Wavell was too intelligent a soldier to ignore the plain reality that the British and Commonwealth forces lacked modern armor and aircraft. Once back in Java, the field marshal cabled Churchill, “Battle for Singapore is not going well … morale of some troops is not good … there is to be no thought of surrender and all troops are to continue fighting to the end.”

No successful Allied counterattack was made against the Japanese. Instead, Percival made a further tactical error by withdrawing inland toward Singapore City. General Yamashita sensed that the next British defensive site would be located on the hill at Bukit Timah, approximately two miles northwest of Singapore City. He attacked on the night of February 10 with his 5th and 18th Divisions. Although the Japanese anticipated a desperate struggle for the island’s highest elevation, confusion among the British and Commonwealth troops led to a rapid loss of the position.

The Japanese did notice that the British were expending their artillery shells as if they had no shortage, while Yamashita’s artillery ammunition stockpiles were running dangerously low. Perhaps it was Wavell’s chiding comments, but to the Japanese commanders the Allied forces were putting up a more tenacious fight. Japanese tanks were halted just south of the settlement at Bukit Timah.

Some Japanese officers were also concerned that if the British held out for several more days they would win the battle since Yamashita’s ammunition kept dwindling. Japanese artillery units had to limit their counterbattery fire on British and Commonwealth guns since they were down to fewer than 100 rounds per gun. Yamashita’s supply system was stretched to the limit.

A few officers had the audacity to suggest calling off the assault and returning to the peninsula for resupply and refitting. However, Yamashita was under intense personal and political pressure to successfully conclude his offensive. To hasten Singapore’s capitulation, Yamashita sent a request for surrender to Percival, warning him of the potential harm that could come to the civilian population of Singapore City should an all-out assault become necessary.

By February 13, the retreating British, Australian, and Indian troops formed a new 28-mile perimeter around Singapore City. Unfortunately for Percival and his defenders, Japanese artillery destroyed the island’s water supply, and the attackers had convinced the British that a major epidemic would ensue without fresh water. The capture of the depots at Bukit Timah had reduced the island’s reserve supplies to just one week. Deserters, refugees, and looters were all around the city.

Percival, sensing that there was still no panic in Singapore City, refused to reply to Yamashita’s surrender request. Yamashita launched into a bluff. He would expend artillery ammunition as if it were unlimited to further convince Percival that he had no alternative but to capitulate.

Forty-eight hours later, Percival had a change of heart. He now sensed a crisis for the civilian and military forces in Singapore City. Although trying to exhort his subordinates as conditions looked bleak on this day, Percival conveyed to Wavell that further resistance and loss of life would be futile and that he anticipated not lasting beyond another 48 hours. Percival cabled Wavell for permission to surrender, but from ABDA headquarters in Java the latter refused and urged the island’s defenders, “You must continue to inflict maximum losses on enemy for as long as possible by house-to-house fighting if necessary. Your action in tying down enemy may have vital influence in other theatres. Fully appreciate your situation but continued action essential.”

After meeting with his commanders on the morning of February 15, Percival decided to surrender despite a personal message from Churchill to Wavell calling for a last stand by the numerically superior Commonwealth forces. Percival cabled Wavell that he would ask for a cease fire at 1600 hours. Wavell acquiesced and gave permission for the surrender if there was nothing more to be done. Percival had no fuel for vehicles; he had nearly exhausted his artillery ammunition, and there would be no water in a matter of hours in a city with more than 500,000 inhabitants. For a personally brave man such as Percival, capitulation was a bitter step, but he chose to ultimately go himself if called for by the Japanese in the hope of obtaining better treatment for his troops and the population.

Percival sought terms from General Yamashita on February 15 as Japanese division commanders were beginning to report severe shortages in ammunition and supplies. Yamashita’s chicanery was successful. At 1100, Japanese lookouts saw through the trees along the Bukit Timah road a white flag hoisted atop the broadcasting studios. Lt. Col. Ichiji Sugita, one of Yamashita’s staff officers, met a British party seeking terms of surrender. Sugita told the British officers, “We will have a truce if the British Army agrees to surrender. Do you wish to surrender?” The British interpreter, Captain Cyril H.D. Wild, assented. Then, Yamashita ordered that Percival and his staff come to the Ford Factory at Bukit Timah.

Six hours after the initial sighting of the white flag, Percival and some staff officers met the 25th Army commander for brief but tense negotiations. Yamashita demanded an immediate surrender, although Percival was doing his best to stall and keep negotiating until the next day.

Yamashita knew his own weakness and did not want any delay.

After the war, Yamashita said, “I felt if we had to fight in the city we would be beaten.” He went on to say that his strategy at Singapore was “a bluff, a bluff that worked.”

At 1950 on February 15, approximately 70 days after the Japanese invasion of the Malay Peninsula, the surrender document was signed. British and Commonwealth losses in Malaya and on Singapore Island totaled 9,000 killed and wounded with more than 120,000 British Empire servicemen taken prisoner. The Japanese lost approximately 3,000 killed and almost 7,000 wounded while completing the greatest military disaster in British history and Japan’s greatest land victory.

Jon Diamond practices medicine and writes from Hershey, Pennsylvania. He is a frequent contributor to WWII History. He is the author of Stilwell and the Chindits: The Allied Campaign for Northern Burma 1943-44, released by Pen & Sword Publishers in late 2014.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments