By Robert F. Dorr

It was loud. It was violent. Gunfire ripped into 1st Lt. Grant G. Stout’s Republic P-47D Thunderbolt fighter high over Dortmund, Germany, near midday on March 19, 1945, and the aircraft trembled and shook. Other pilots saw Stout’s P-47 begin shedding pieces.

Stout’s mission leader, Major Arlo C. Henry, Jr., later said the Thunderbolt was hit in the engine. According to Henry, Stout had been on his way home from a dive-bombing mission when he spotted a German train, rolled over, and went down to strafe it. A squadron report differed slightly from Henry’s recollection, saying that Stout was strafing a truck. Many decades later, a researcher would claim that Stout’s target was neither a train nor a truck but something far more macabre. Said Henry, “Stout’s parachute was seen to open and land safely.”

Because Stout was a big, husky guy who seemed cramped even in the famously roomy cockpit of a P-47, his buddy, 1st Lt. Allen V. Mundt, had pleaded with him to exchange his standard 24-foot parachute for a larger, 28-foot model that was available only upon special request by the supply sergeant. Stout had apparently requested the larger chute but had not yet gotten it.

Also in the air with Stout, Henry, and Mundt was 1st Lt. Donald E. Kark, who saw Stout’s Thunderbolt get hit, but unlike Henry and Mundt, did not observe the bailout. Kark did see the chute on the ground a few minutes later. He remembers thinking that Stout was now a prisoner of war. In fact, Stout was in the final minutes of his life, a situation he almost appeared to have foreseen.

Before the mission during which he hit the silk over Germany, Stout allowed a buddy to take a snapshot of him standing in front of a P-47, “map in hand, poop in pocket, and raring to go,” as he wrote to his sister Lyla. “The boys gave me that old ‘song’ about having your picture taken before a mission,” wrote Stout, hinting that posing for a photo was tantamount to inviting a jinx. “I needed to go out and explode that superstition.”

Almost two years after the war ended, the U.S. War Department informed Stout’s family that the P-47 pilot’s remains had been recovered from an isolated grave near Dortmund. Stout had been reburied, the Pentagon told his family, at the U.S. military cemetery in Nouville-sur-Condroge, near Liege, Belgium. In 1949, his remains were disinterred and moved to his home in Pike, New York. His mother was not convinced it was her son’s body. Someone told members of the family that Stout had been mortally injured in the bailout. The family did not believe that could happen. And if a pilot bailed out successfully, he was supposed to be accorded humane treatment as a prisoner of war.

Grant’s mother, his sister, and others in the family all wondered: What happened to Grant Stout?

“We learned the truth only in 1997,” said Stout’s sister, Lyla K. Stout, 78, of Rochester, New York, referring to the shocking revelation that Germans on the ground had murdered Stout. She was wrong. Half a century after the war, she had learned only part of the truth.

Stout’s story is the saga of a citizen-soldier—in his sister’s words, “a young farm boy who wanted to fly and who ended up doing exactly what he wanted to do.” It is also the story of a big, burly warplane that was built in greater numbers than any other fighter in the United States and was as tough as a tank.

Grant Stout was born in 1922 in Pike. His parents owned a 181-acre farm that harvested potatoes and grain and had a milk dairy. Following high school graduation in 1941, he worked in a munitions plant where he earned money for private flying lessons. “Our mother was not aware of this until he flew over the farm and waved to her,” Stout’s sister recalled. “It was a thrill for both of them, although of some concern to our mother.”

Stout was a strapping, athletic figure. A member of Army Air Forces’ flying class 43-J (along with 1st Lt. Donald E. Kark, who would later be in the air with Stout over Dortmund in the final minutes of Stout’s life), Stout was one of thousands of AAF aviation cadets who underwent primary training in the Stearman PT-17, basic training in the Vultee BT-13 Valiant (or “Vibrator,” the men called it), and advanced training in the North American AT-6 Texan. After seven hours of instruction, he made his first solo flight in the PT-17 at Avon Park, Florida, on May 15, 1943. “I was the second in our group of 200 men to solo,” he wrote home. In one of several pessimistic comments that seem prescient when viewed later, he wrote of how eagerly he wanted to succeed as a pilot, but, “There will be a lot of hard work and … the ‘law of averages’ is against me.”

While in basic flight training at Gunter Field, Florida, Stout wrote home with unconcealed enthusiasm about a new fighter he had seen. “Last Saturday afternoon we had a P-47 Thunderbolt show,” he wrote. “They brought four of them over from a nearby field and they showed off to us, doing loops and other acrobatics in a very tight formation. Our instructors were all sore because the big shots made us take time off to watch them.”

Stout’s biggest thrill, simply, was becoming a pilot of a P-47 Thunderbolt, an aircraft that evoked fierce loyalty from pilots. It did not happen immediately.

From Spence Field, Moultrie, Georgia, still in training, Stout wrote home on October 22, 1943, that he had now accumulated six hours in the P-40F Warhawk. On November 3, he sent a telegram to his parents with the happy news that he’d pinned on pilot wings and second lieutenant’s bars. Soon afterward, at Richmond, Virginia—finally—he was introduced to the P-47 Thunderbolt. He wrote home, “Imagine landing at 130 miles per hour!” A few days later, he wrote, “This Thunderbolt is more like a rocket ship than an airplane. You have no idea how powerful those 18 cylinders are until you get hold of the throttle and then she really goes places.”

Not for nothing, the Farmingdale, New York, manufacturer of the Thunderbolt was called the “Republic Iron Works” and had a reputation for building fighters that were big, roomy, and robust.

The typical P-47D flown on the European continent by Stout and other pilots had a 2,535-horsepower Pratt & Whitney R-2800-59W Double Wasp 18-cylinder, twin-row air-cooled radial engine; a 17,500-pound takeoff weight; and eight .50-caliber (12.7mm) Browning M3 machine guns packing 250 rounds each.

P-47s rolled out of American factories in greater numbers than any other U.S. fighter, ever. The total of 15,683 P-47s compares to 15,486 P-51s, 13,143 P-40 Warhawks, and 10,037 P-38 Lightnings. But while the Thunderbolt was plentiful, P-47 pilots became accustomed to being slighted. In an appalling gaffe, the U.S. National Air and Space Museum did not have a P-47 on permanent display until 2003 when the museum opened its Udvar-Hazy Annex at Dulles Airport near Washington, D.C.

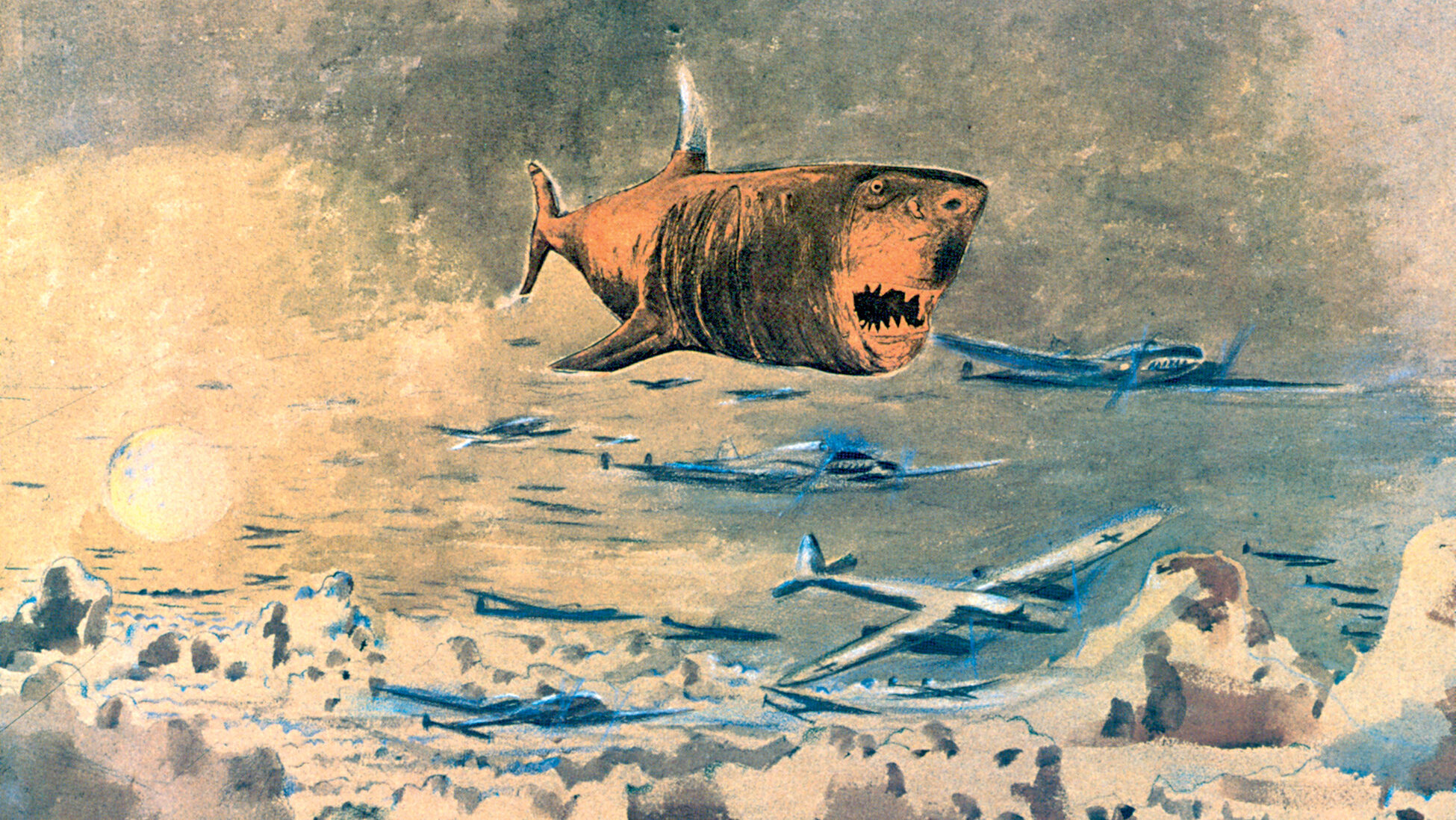

On a museum floor, clean and silvery and surrounded by other aircraft, the “Jug”—as the Thunderbolt was nicknamed for its portly shape—might look like a high flyer. But Grant Stout and his buddies fought their war down in the treetops, where they came face to face with the German foe. It was a dirty war, fought eyeball to eyeball, and it saw its share of grit, gristle, and blood. Consider, for example, the following citation awarded to P-47 pilots for destroying a column of German vehicles attempting to escape advancing Allied forces near Chateauroux, France:

“Thirty-six P-47’s … raced south of the Loire River to find the road from Chateauroux to Issoudon clogged with military transport, horse-drawn vehicles, horse-drawn artillery, armored vehicles and personnel. Attacking this [German] concentration, at minimum altitude, in spite of accurate ground fire, the … pilots … made pass after pass until their bombs, rockets, and ammunition were expended. The road was blocked for 15 miles with personnel casualties, wrecked and burning military transport. More than 300 enemy military vehicles were destroyed in this attack alone.”

The citation continues: “The group returned to home base, and after being refueled and rearmed in minimum time, returned to the scene of the action. Before the enemy could reorganize and extract the remnants of his column, a further 187 vehicles, including 25 ammunition carriers, were attacked and destroyed. In spite of intermittent rain and the hazard of landing at night on a slick tar paper runway….”

Left out of the citation is the fact that Thunderbolts frequently strafed horse-drawn supply columns, leaving behind tangled, bloody carcasses. One of Grant Stout’s fellow P-47 pilots remembered, “The horses were not our enemy, but our assignment was to prevent those columns from harming our troops.” The gruesome sight sometimes made pilots physically ill.

P-51 Mustang pilots on high-altitude escort missions may have found moments to savor the joy of flying that had prompted most to join the air force. But for Grant Stout and other pilots in the 365th Fighter Group, the “Hell Hawks,” the job meant living in infantry-like conditions at snow-covered, mud airstrips on the Continent and flying low-level strafing and bombing runs—“not clean, not comfortable, and certainly not glamorous,” said another 365th pilot, “but necessary….” In Stout’s outfit, the 365th Group’s 387th Fighter Squadron, Fighter Group “Hell Hawks,” one P-47 returned to its European base with body parts from a German soldier embedded in its engine cowling. Another landed safely riddled with 138 holes from bullets and shrapnel.

Stout almost didn’t survive long enough for his 1945 rendezvous with destiny in Germany. When his fighter group came ashore after the Normandy invasion, Stout was observed to retain his usual sense of humor—he had a pet duck named Zeke—but he also spoke, occasionally, as if something bad lay ahead.

Shortly after D-Day, Stout and his buddies began carrying out strafing runs that brought them low enough to see the upturned faces of Wehrmacht soldiers. Major Arlo C. Henry, a flight commander, wrote to Stout’s parents of their son’s D-Day exploits: Grant “shot up so many enemy supply vehicles that he had only one [.50-caliber] gun firing when he spotted four German soldiers firing at him … He got three of them and the last one was running along a wall, trying to make the corner. [Stout’s gun camera] film showed the bullets clipping the wall about two feet above the German’s head as he ran.”

On an August 8, 1944, mission led by Lt. Col. Don Hillman, the “Hell Hawks” were attacking their assigned targets of ammunition bunkers at Pre en Pait, France, where all bombs were dropped, but no secondary explosions were seen, making it doubtful that the ammunition bunkers were destroyed. The pilots then went on a strafing attack in the area and destroyed four trucks in two attacks near Putganges. During the attack on the trucks, Stout’s Thunderbolt was hit by flak, and he personally was hit. He was able to fly his plane back to Fontenay-sur-Mer where he landed. He had to bring the P-47 to a halt without working brakes, and stepped out of the fighter with a serious laceration on his foot. Because of the wound, Stout was briefly assigned a half-track and a driver to enable him to act as a forward ground observer; eventually he went back to flying.

He wrote home about seeing a German Messerschmitt Me- 262 jet fighter and admiring it:

“The day Grant was shot down was bright and sunny,” 1st Lt. Allen V. Mundt later wrote. “It was a morning mission for the purpose of attacking ground transport of all sorts. There were a lot of trains out that day. They proved very vulnerable up to the time Grant and I saw this last one just before we regrouped to go home. He didn’t know until it was too late that the train was heavily armed with flak guns. I was far enough behind on the initial run to be able to pull up but Grant’s plane flew right through a cloud of flak. He pulled up then too and seemed to have good control for a minute, but then the ship rolled over and went down. I saw his chute open a split second after the ship crashed.” Mundt learned nothing more about Stout’s fate until decades after the war.

After the war, Stout’s remains were repatriated, but family members were told nothing of his cause of death.

Even while reeling under bombing and strafing attacks, most Germans treated downed Allied pilots with respect and humanity. Most simply became prisoners of war and lived in reasonable comfort until the end of hostilities. On the very rare occasions when Germans violated the law of war by killing a downed pilot, the perpetrators were usually civilians rather than uniformed members of the Wehrmacht or Luftwaffe.

In Stout’s case, it was different. In the 1990s, a Canadian doctor, Robert Reid of London, Ontario, was researching a related topic when he learned about one of hundreds of low-level war crimes trials held by U.S. authorities after the war. Reid uncovered documents from a U.S. tribunal held in Dachau in July 1947. Four Germans were convicted and sentenced, one to life imprisonment.

An official summary of the U.S. war crimes trial says that the commander of the German antiaircraft battery at Brackel, on the outskirts of Dortmund, placed the downed P-47 pilot in front of townspeople and “incited the crowd to beat and kill the flyer.” According to the summary, four Germans, led by 1st Sgt. Georg Mayer, used clubs, stones, and a shovel to brutally attack the P-47 pilot. The summary says Mayer shot Stout with a pistol. Mayer was sentenced to life imprisonment for the killing and is thought to have died while imprisoned by U.S. occupation forces.

It was unusual for a German military member to perform such an act, but this was the “truth” Stout’s sister learned in 1997. Later, she said, “We just want to be sure that Grant’s service to his country is remembered.”

If the story ended there, it would be a tragedy. Stout, after all, deserved to be captured, treated as a prisoner, and released at war’s end. But the tragic tale of the strapping P-47 pilot does not end there.

Canadian researcher Reid, who visited Dortmund and has worked in collaboration with a German researcher, believes the war crimes trial convicted the wrong culprits. Reid and the German researcher concluded that civilians, not Luftwaffe antiaircraft artillerymen, killed Stout and that the murder weapon was a shovel, not a pistol. Finally, while all Americans who participated in the mission say Stout was strafing a train, the two researchers say American fighter planes strafed civilians that day, including a funeral procession for a small child. There is no way to be certain after all this time, and the proposition is questionable at best, but it suggests that there may never be a wholly satisfactory answer to the question: What happened to Grant Stout?

No matter what the Thunderbolts were firing at, and no matter how much people on the ground suffered, international law requires captors to protect a downed airman who is unarmed and has surrendered. On that day, the law and the system failed Grant Stout.

Along with Army soldier Theodore Hunt, Stout is one of only two residents of Pike, New York, to lose his life in World War II. Today, the Hunt-Stout Post of the American Legion in Castile, New York, near Pike, is named for the two men.

Robert F. Dorr is an Air Force veteran, a retired U.S. diplomat, and author of the book Air Force One, a look at presidential aircraft and air travel. Don Hillman, Donald E. Kark, Allen V. Mundt, Lyla Stout, and Robert Reid were interviewed for this article.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments