By Don Williams

The struggle for the Devil’s Den at Gettysburg occurred on July 2, 1863, under a hot and cloudless afternoon. Tens of thousands of soldiers in blue and gray had spent the morning in the humid, uncomfortable heat, maneuvering for position and occasionally exchanging shots as they eyed one another with resolution. For more than a day, portions of the two armies had ferociously grappled with one another in and around the small but strategically situated town of Gettysburg.

Up to this hour the battle had gone in favor of the Confederates, whose superior numbers had pushed two Union corps back through the town and onto a ridge and several hills that lay to the southeast. The victorious Rebels had not pressed their advantage, though, and by the preceding evening, U.S. General Winfield Scott Hancock had managed to establish a solid line of defense on Cemetery Hill with Union reinforcements.

Union Army commander Maj. Gen. George G. Meade had arrived on the field too late to witness the fighting. But after a quick survey of the field he readily agreed with his subordinate generals that Cemetery Hill and neighboring Culp’s Hill were suited for a defensive battle should Lee wish to continue his attack the following day.

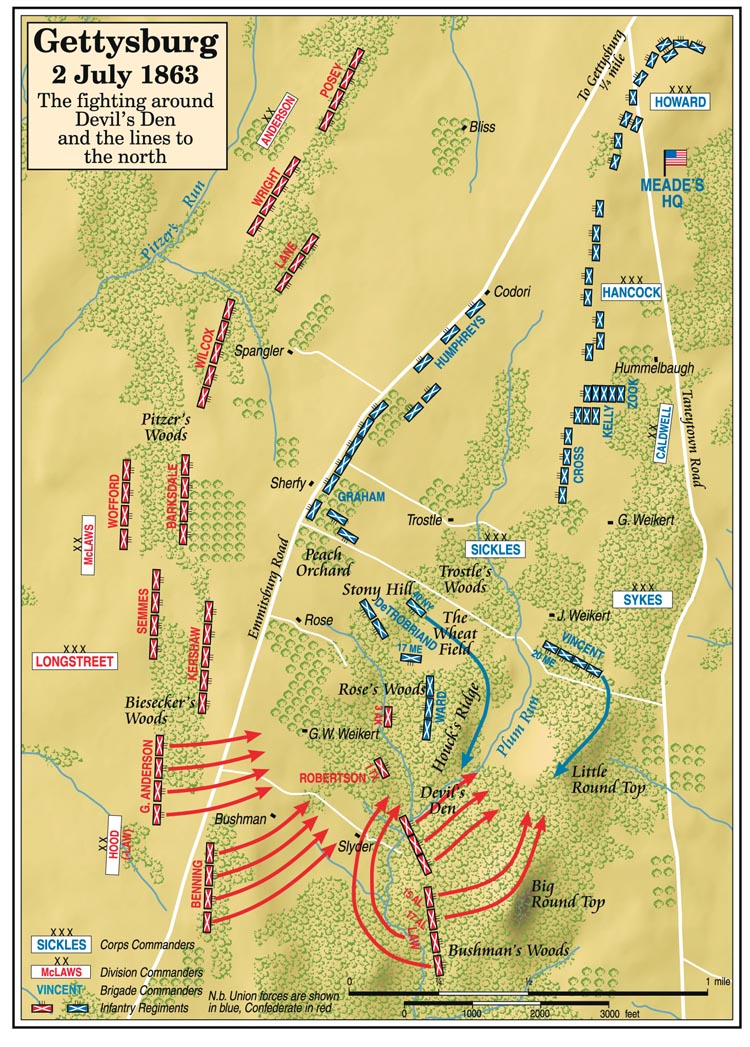

Standing alone, however, this high ground was insufficient to guarantee a satisfactory outcome for the Union. To the left of Cemetery Hill, a low-lying ridge ran south through relatively open country along the Taneytown Road toward two more hills known locally as the Round Tops. Meade decided that his III Corps, led by Maj. Gen. Daniel Sickles, was best suited to protect this vulnerable flank from attack. Although Sickles’ Corps was among the smallest, it was the obvious choice for the job, because his men had spent the previous night encamped nearby after having made a forced march from Emmitsburg, Md., on muddy and almost impassable roads. Later in the morning, Meade ordered V Corps to occupy a position in support of Sickles near the Round Tops.

Sickles followed Meade’s instructions, placing his two divisions adjacent to Hancock’s II Corps along Cemetery Ridge. Around noon, however, worrisome news arrived from units Sickles had dispatched to reconnoiter the territory in front of his position. Confederate troops in large numbers were reportedly moving to occupy some high ground in the vicinity of the Wentz and Rose farms near the Emmitsburg Road. Should this area fall into Rebel hands, Sickles would be at a disadvantage, because his troops—even on what was left of the declining Cemetery Ridge—would be exposed to plunging fire.

Sending word to Meade of his intentions, Sickles ordered his two divisions approximately one mile forward of Cemetery Ridge. Marching out with full colors flying and brigade bands playing, Sickles positioned Brig. Gen. Andrew A. Humphrey’s 2nd Division facing west along the Emmitsburg Road for about a half-mile stretch. Major General David B. Birney’s 1st Division continued this line by curving back to the south at a right angle at the Wentz farm peach orchard for another half-mile.

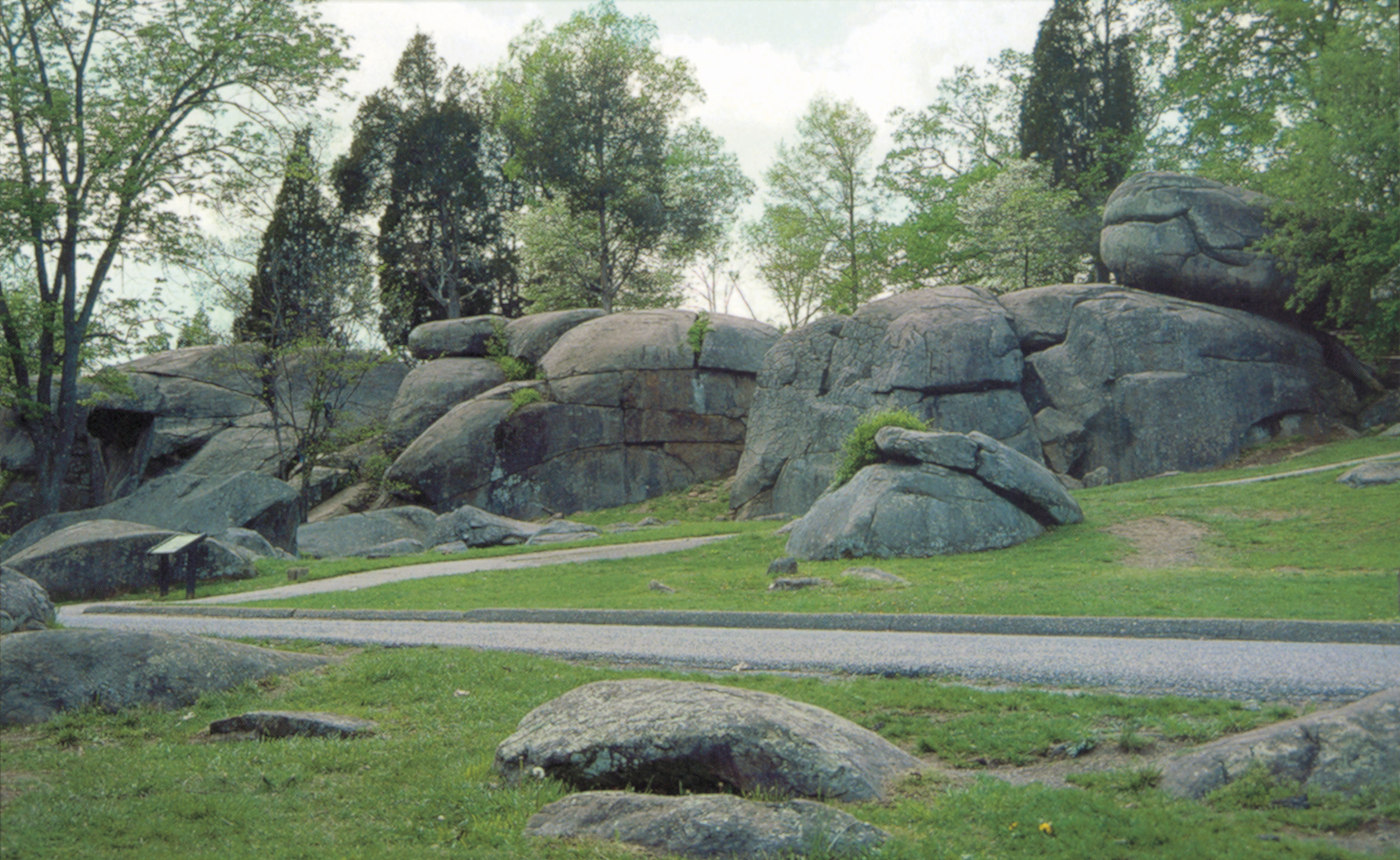

The Devil’s Den at Gettsyburg: Origin of the Name

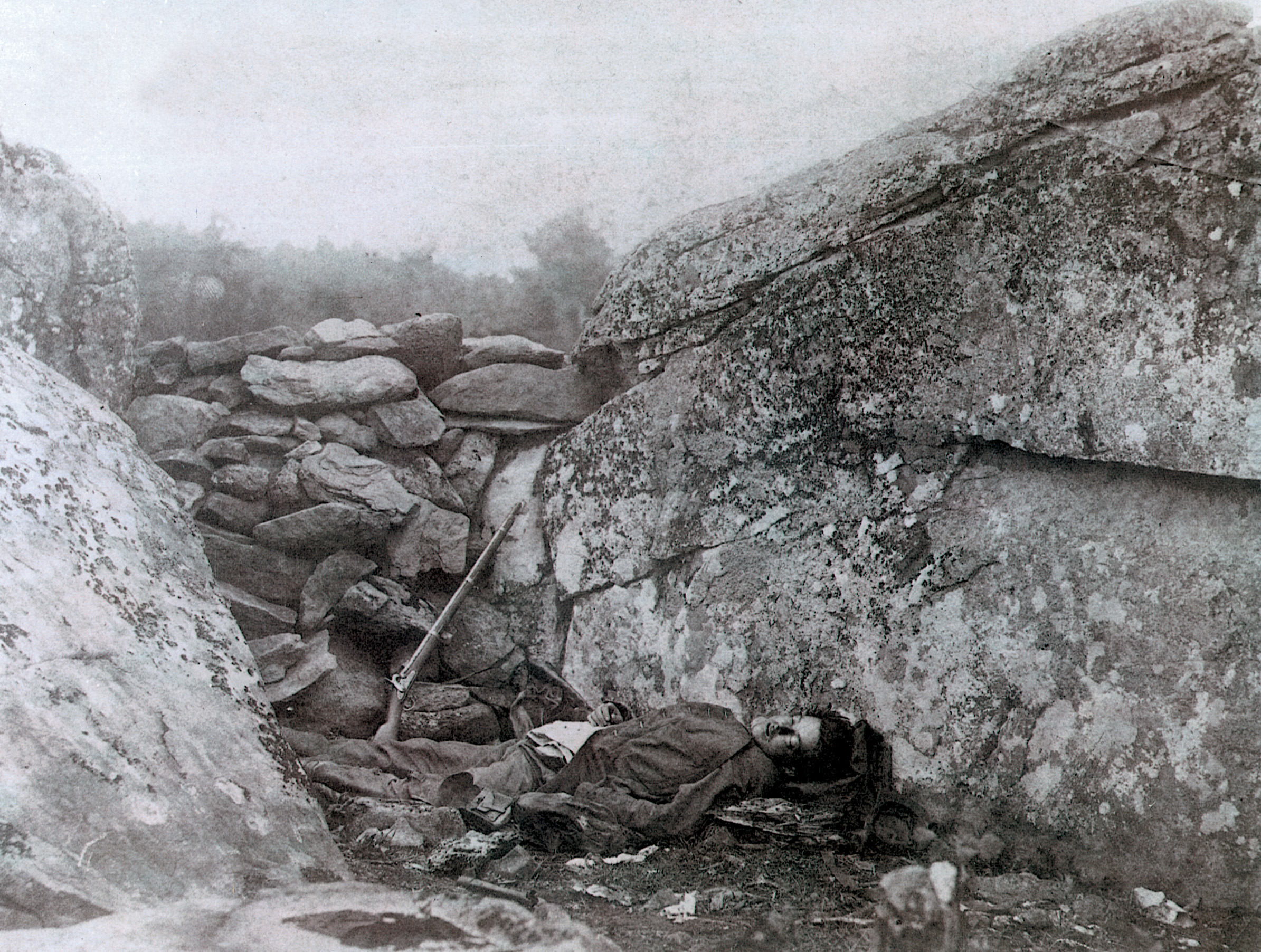

On the far left flank of Sickles’ line was a rise of mostly barren, rock-strewn ground known as Houck’s Ridge. To the south and running almost perpendicular to the ridge was a stream called Plum Run. It meandered through a gully of large boulders overgrown with vines and bushes. This area was called “Devil’s Den” or Devil’s Cave by locals, being named after a large rattlesnake known as the “Devil” that had occupied it in the early days of pioneer settlement. On the far side of Plum Run lay the heavily wooded slopes of Round Top, also called Sugar Loaf Hill, whose rocky crest was almost a half-mile from the creek. Adjacent to this hill and lying to the rear of Houck’s Ridge was a smaller, rock-strewn hill called Little Round Top which had recently been cleared of timber. Sickles had insufficient men to cover the hills in this sector, leaving the far left of the Union line vulnerable to attack.

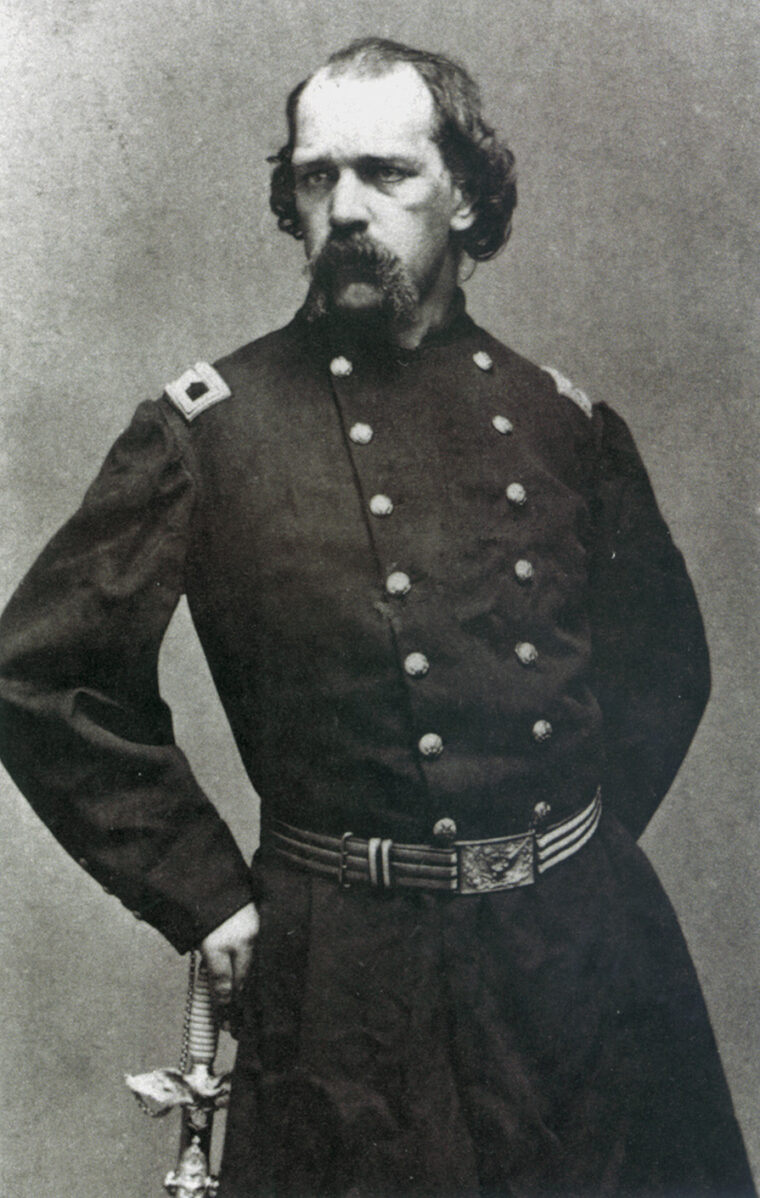

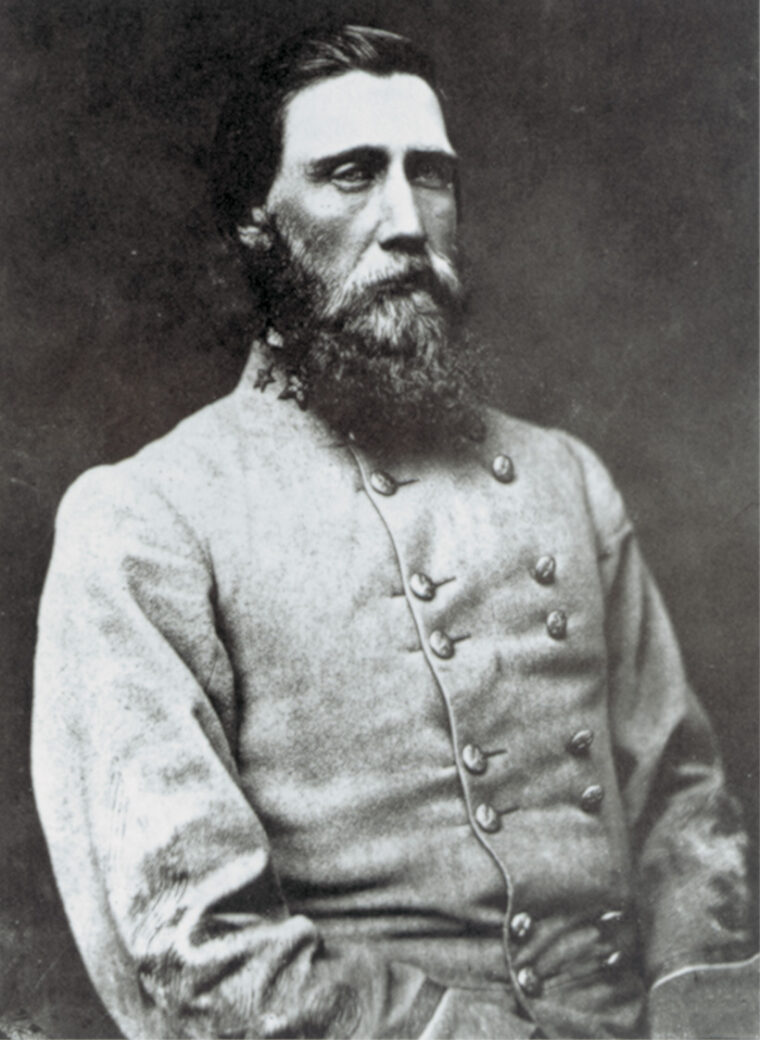

The battle for this portion of the field began shortly after the arrival of approximately 1,500 Yankees from the 2nd Brigade of Birney’s Division under the able and experienced command of Brig. Gen. J.H. Hobart Ward. The 40-year- old Ward was a native of New York City and came from a family of soldiers—his grandfather had served in the American Revolution and his father in the Mexican War. Ward himself had enlisted in the 7th Regiment of the U.S. Army at age 18, rising to the rank of sergeant major in just four years. He, too, served in the Mexican War, receiving wounds at Monterrey and again at Vera Cruz where he was also captured. After the war, he served as Commissary General of New York. When the call to arms came in 1861, he recruited the 38th New York Volunteers and served as the regiment’s colonel until earning a promotion to command of the 2nd Brigade in the fall of 1862.

Ward Commanded Two Elite Sharpshooter Units

Ward’s Brigade comprised eight regiments—most of whom had seen hard service over the previous year in the battles of the Peninsula, Second Bull Run, Fredericksburg, and most recently Chancellorsville. This was attested by the fact that virtually all of them counted fewer than 250 men in their ranks, and several had less than 200. The core of Ward’s Brigade consisted of four old veteran regiments: the 20th Indiana, the 3rd and 4th Maine, and 99th Pennsylvania. A few months earlier, they had been joined by the 86th and 124th New York of Whipple’s now defunct 3rd Division. Although less experienced, both had seen heavy action at Chancellorsville. All proudly wore the symbol of the red diamond on their forage caps, known affectionately by the 1st Division as the “Kearny patch” after their commander Phillip Kearny, killed leading his men at Second Bull Run.

Ward also had under his command the 1st and 2nd U.S. Sharpshooters. These were elite units of expert marksmen dressed in dark green uniforms who often served on detached duty. In fact, on July 2, both the 1st U.S. Sharpshooters and the 3rd Maine operated independently of Ward under Colonel Hiram Berdan. They spent the early afternoon of July 2 engaged in skirmish duty near the center of III Corps’ position.

Ward’s Brigade arrived at the ridge at about 3:30 pm and was formed up into battle order. Ward sent out the 2nd U.S. Sharpshooters under Major Homer R. Stoughton as skirmishers about a half-mile ahead. He then deployed four of his regiments over a space of about 450 yards along the crest of the ridge. Lined up shoulder to shoulder was the 20th Indiana on the right, followed by the 86th New York, 99th Pennsylvania, and 124th New York, which was situated just above Devil’s Den. Much of the brigade was positioned in woods. The only exception was the 124th New York and an adjacent company of the 86th New York, which were completely out in the open. Off to the right, separated by a gap of about 250 yards, lay Colonel Regis de Trobriand’s 3rd Brigade. It was formed up along a stone wall and in some woods with its rear lying at the edge of a large wheat field. No efforts were made to construct breastworks by any of these men.

Soon thereafter, Ward’s men were joined by Captain James E. Smith’s 4th New York Battery, which was sent to support Birney’s defense of this position. Smith quickly sized up the situation and decided to place four of his six 10-pound Parrot rifles on the left side of Ward’s Brigade in the exposed area at the top of the ridge. Another section of two cannon along with the battery’s caissons and horses were sent 150 yards farther south and to the rear in the Plum Run valley to cover the left flank. It was difficult work, because the rocky slopes were steep, and the ridgeline contained little in the way of flat ground suitable for placing cannon. As these guns were being moved into position, the first shots from Confederate cannon located a half-mile distant began to fall along the ridge.

Seeing the logic of Smith’s decision to cover the Devil’s Den flank, Ward sent off nine of the 10 companies of the 4th Maine under Colonel Elijah Walker to bolster Smith’s two detached guns. Picking their way down into the low marshy swale, these men formed a rough line in the midst of the boulders located on the northern rim of Devil’s Den that stretched across to the far side of Plum Run. Wary of surprises, Walker then sent a company of skirmishers forward (south) into the valley, while another squad was deployed to the left on the lower slopes of Round Top.

Walker Makes a Regrettable Tactical Error

Smith soon rode up to Walker and pleaded with him to remove his men to the far side of Devil’s Den and form them in the woods at the base of Round Top. He argued that he could take care of his own front well enough with two guns, but feared that their flank would be turned if the Rebels controlled this strategic point. Walker did not comply, a decision he would soon regret.

Less than a mile away, the first troops of Maj. Gen. John Bell Hood’s Division of Lt. Gen. James Longstreet’s Corps began stepping out from Seminary Ridge. Others would soon follow all along Longstreet’s front, which stretched a mile and a half toward the direction of the town of Gettysburg. Seeing the advance pickets of Hood’s troops off in the distance, Smith immediately ordered his four cannon on the ridge to shift their fire toward the ominous ranks of gray. At this distance, case shot was used when enemy lines were observed in the open, and solid shot when they were seen moving through trees. Several Confederate batteries, including Latham’s and Reilly’s, kept up a sharp return fire from a position just to the rear of the assaulting Rebel lines.

Brigadier General Henry Hunt, Meade’s chief of artillery, appeared at this time in the midst of the 4th New York artillerymen, and conferred with Smith among the exploding shells around them. While effective at long range, it was evident that Smith’s battery would be unable to depress their muzzles far enough to sweep much of the steep slope to their front, and Hunt believed the position untenable. Seeing that the artillery was already engaged, though, he saw no point in ordering Smith off the ridge. Confederate shots landed to the rear of the ridge in the midst of a cattle herd, causing a stampede that nearly crushed Hunt as he moved to the rear.

Although Hood’s advancing lines took casualties all along their path of assault—Hood, too, was severely wounded—the artillery fire did little to deter the momentum of the attack. More destructive was the accurate skirmish fire from Stoughton’s sharpshooters, which forced at least one regiment in the Rebel line to break three times and run to the rear. Once the Rebel forces passed through this fire in the open fields of the Timbers and Rose farms, however, they benefited from cover provided by the reverse slope of a slight hill and woods about 200 yards in front of the main Federal position.

Ward’s Skirmishers Received a Withering Volley of Bullets

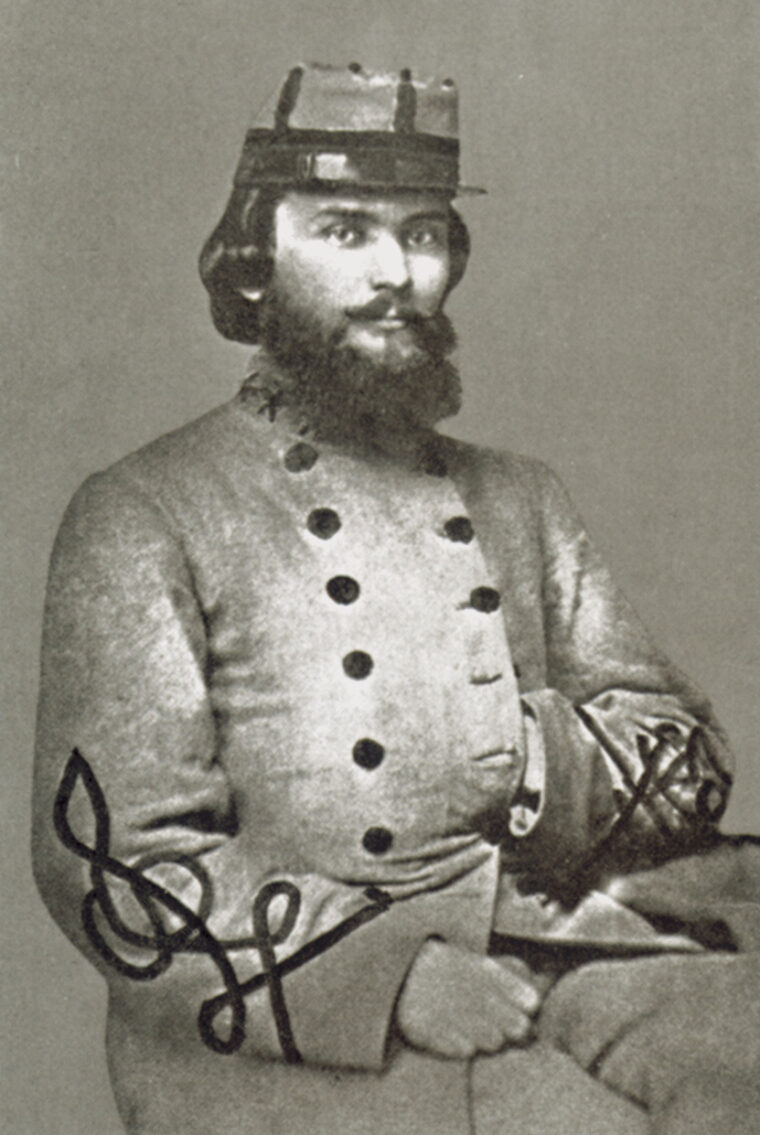

The first Confederate troops to appear in front of Ward’s main line were the 3rd Arkansas and 1st Texas Regiments of Brig. Gen. Jerome Robertson’s Brigade. They came into view formed up in columns yelling and shouting at the edge of a triangular-shaped field that came to a point just below the crest of the ridge. Pushing back Ward’s skirmishers from the 99th Pennsylvania, they received a withering volley at 200 yards from the well-prepared ranks of blue lining the top of the ridge. This caused the gray ranks to pull back and retreat down the rocky slope while the Yankees quickly reloaded their weapons. Another assault was made back up the hill less than 15 minutes later, this time more deliberately as the Confederates made better use of the stone walls and rocky outcroppings for protection. They were also given the assistance of two more regiments that appeared on their right. These were the 44th and 48th Alabama, which were part of Brig. Gen. Evander Law’s Brigade that was heading toward the wooded slopes of the Round Top.

About this time, Colonel William Perry of the 44th Alabama was instructed by Law to aim his regiment for Smith’s Battery with the intention of capturing it. Unfortunately for these Confederates, their assignment would be full of danger. Working their way with some effort through the rocks and boulders of Devil’s Den at Gettysburg, the 44th Alabama was hit without warning by a well-aimed canister charge from the two 4th New York guns, joined by several volleys from the concealed skirmishers of Walker’s 4th Maine.

As the 44th pulled back to regroup, skirmishers from the 2nd U.S. Sharpshooters appeared among Walker’s men farther up the creek. Forced to withdraw due to low ammunition, they warned the men of the 4th Maine that they were being outflanked by more Rebels coming down through the woods of Round Top. Hardly had this warning been given when advance elements of the 48th Alabama came into view. The officers of the 4th Maine immediately refused the left flank of their line to meet this new threat and opened up on the approaching enemy. Volleys were exchanged at 20 paces. Although the portion of the 48th that was in the Plum Run gully pulled back quickly, those men who were better concealed on the slopes of Round Top remained, causing heavy losses among the 4th Maine. As the blue and gray ranks mixed together, Smith’s two cannon located to the rear had to cease their fire in order not to hit Union soldiers in their fire zone.

Up until this time, the Federal line on Houck’s Ridge had held firm against all that Hood could throw at it. After the second assault was repulsed, Ward even pushed the 270 men of the 86th New York forward about 50 yards to a stone wall to maintain a harassing fire on his opponent. Even so, the pressure on Ward’s front and left flank increased as additional units from Hood’s other brigades were sent in to support the attack. Concerned about his left, Ward shifted the 99th Pennsylvania off the ridge and sent them down into Devil’s Den to bolster the 4th Maine. This left the 20th Indiana alone to fend off attacks on the far right of Ward’s Brigade. To compensate, Lt. Col. William Taylor formed Companies B and H of his regiment into a skirmish line that reached back into the woods.

Meanwhile, word was sent back to the rear that Ward’s Brigade was running low on ammunition. The situation was looking grim all along the 1st Division line, as division commander Birney was well aware. Seeking to compensate, he began to dispatch regiments from one brigade front to another to hold his line intact. He reported later that “my thin line swayed to and fro during the fight, and my regiments were moved constantly on the double-quick from one part of the line to the other, to re-enforce assailed points.”

Desperate, Colonel Ellis Makes a Bold and Risky Move

On the ridge, the men of the 4th New York Battery kept up a rapid fire that soon exhausted their supply of canister and case shot. Undeterred, Smith ordered his gunners to use shell as well as solid shot to maintain the pressure on the surging enemy line down below, even going so far as to order them not to waste time sponging the guns—a desperate measure that endangered the men working the cannon. By this time, the Confederates had advanced to within only 20 to 30 yards of the thin Federal line on the crest of the ridge. It looked as though Hunt’s prediction was about to come true.

It was at this desperate moment that the commander of the 124th New York decided to turn the tables with a bold and risky move. Sensing that his line was vulnerable to the superior numbers of the enemy working their way up the slope, Colonel Augustus Van Horne Ellis mounted his gray horse and ordered his small regiment of just over 200 men to fix bayonets and follow him in a countercharge down the hill. The “Orange Blossoms,” as the regiment from Orange County, NY, was known, stood up in unison, let out a cheer, and faithfully followed their young colonel down through the lines of Confederates. This impetuous action broke the momentum of the Rebel attack, sending Southerners scurrying down into the protection of the rocks and woods at the base of the ridge to elude capture.

The impetus of the 124th New York charge would not last long. Joined now by reinforcements from the 15th Georgia of General Henry A. Benning’s Brigade, Robertson’s Brigade of Texans quickly turned and began to fire into the ranks of the intrepid New Yorkers. The New York regiment came to a halt at the base of the ridge, where about a quarter of its number fell, along with Ellis and his major, James Cromwell, both of whom were knocked off their horses and killed. Facing imminent capture, the remainder of the 124th New York gathered many of their wounded and slowly fell back to the crest of the corpse-strewn slope. Although it could not stem the entire assault, the New Yorkers’ counterattack compelled the Confederates to sort out their lines before renewing their attack.

Within the hour, all three brigades commanded by Robertson, Law, and Benning were in position to launch a more concentrated assault back up the slope. Now supported by several of Anderson’s Georgia regiments that had worked their way through the Rose Woods, this last charge finally broke through to the top of the ridge. In actuality, there was little real fighting during this phase of the Houck’s Ridge battle, because Ward had ordered his exhausted brigade—most of whom were out of ammunition—to retreat behind the ridge in the direction of the Wheat Field. Cheers rang out among Hood’s men as they triumphantly reached their objective, which included Smith’s three Parrot rifles (one had been damaged and removed earlier).

“For Pennsylvania and Our Homes!”

Meanwhile, down along Plum Run, Benning ordered the 2nd and 15th Georgia into Devil’s Den while another of his regiments, the 17th Georgia, joined with the Texans in the final assault up Houck’s Ridge. These men moved forward at a run and overwhelmed the Federals’ advance line, capturing about 40 men who had been occupying positions among the large boulders. Unaware that he was outnumbered, Colonel Walker of the 4th Maine responded to the Confederate advance by ordering his men to fix bayonets and counter charge. Joining in this effort, Major John Moore of the 99th Pennsylvania ordered his men to attack, shouting, “For Pennsylvania and our homes!”

The counterattack was surprisingly brief. Scattered elements of several Confederate regiments at the top of the ridge were hit unawares and quickly pulled back down the hill, temporarily abandoning the three cannon they had just claimed. The triumphant Federals did not remain long themselves. Finding the ridge was no longer a part of the Yankee line, they too were withdrawn to the rear. The cost was heavy though: Each regiment had lost many of their number, including Colonel Walker and his major, Ebenezer Whitcomb. In spite of severe wounds, however, Walker refused to leave and stayed with his men until they fell back. As they retreated, Sergeant Henry O. Ripley—the last survivor of the 4th Maine color guard—defiantly waved his flag in the face of the enemy. A total of 31 new bullet holes were later counted in its folds.

Still the see-saw fight was not over. The men of the 40th New York had arrived, having been ordered away from de Trobriand’s Brigade rather belatedly to provide support for the depleted 4th Maine near Plum Run. This regiment from New York City was known as the “Mozart Regiment” because it had been sponsored by the Mozart Hall Committee, a part of the city’s Democratic machine. Unaware of the Union intention to abandon Houck’s Ridge, Colonel Thomas W. Egan formed his men just up from Plum Run and ordered them forward to plug the gap that had been left by the Maine and Pennsylvania regiments. As they moved forward into Devil’s Den, they ran headlong into the ranks of the 17th and 2nd Georgia, which were cautiously advancing through the gully amid the destructive fire from Smith’s two remaining guns. The Rebels fell back behind the large boulders along Plum Run to take cover, and then opened fire. They had assistance from several companies of the 48th Alabama, which were still positioned behind rocks and trees on the lower slopes of Round Top.

A short and vicious fight ensued, with repeated attempts by the 40th New York to dislodge the Confederates. There was much confusion in the smoke-filled defile, obstructing the view of all combatants. The crash of iron and lead against the granite rocks and the concussion of sound from rifle and artillery blasts further added to the terror. Even after another III Corps unit, the 6th New Jersey, joined in supporting the attack, no headway was made in an area that became known as the “Slaughter Pen” by the end of the battle.

Covered by the arrival of the 6th New Jersey on its right flank, the 40th New York eventually pulled back from Devil’s Den in the direction of the Wheat Field. Here, its commander had difficulty rallying the regiment because Confederates from Houck’s Ridge were now descending into the valley and threatening their flank. Within the next few moments, the last two guns of Smith’s beleaguered battery were withdrawn along with the 6th New Jersey, thereby conceding this portion of the battlefield to the advance regiments of Hood’s Division.

The Fate of Devil’s Den at Gettysburg

Although intense and bloody fighting would continue nearby in the Rose Woods, Wheat Field, and along the slopes of Little Round Top for the next hour, the Confederate assault on Devil’s Den was over by 6 pm. The Rebels had outflanked and outgunned the left flank of the III Corps before it could be sufficiently reinforced by the arriving brigades of the V Corps sent by Meade. Although more could have been done to recapture Devil’s Den, once the adjacent land in the Wheat Field and Rose Woods was taken by Hood’s men later in the evening, this section of the field was no longer defensible.

But the fighting in and around Devil’s Den was still not quite over. Sporadic fighting would continue over the next two days as Union forces positioned on Little Round Top traded shots with Confederate units that dug in and around Devil’s Den. Still more men would fall amid the rocks and boulders of the gorge and adjacent ridge, at times receiving wounds from ricocheting bullets and shell fragments.

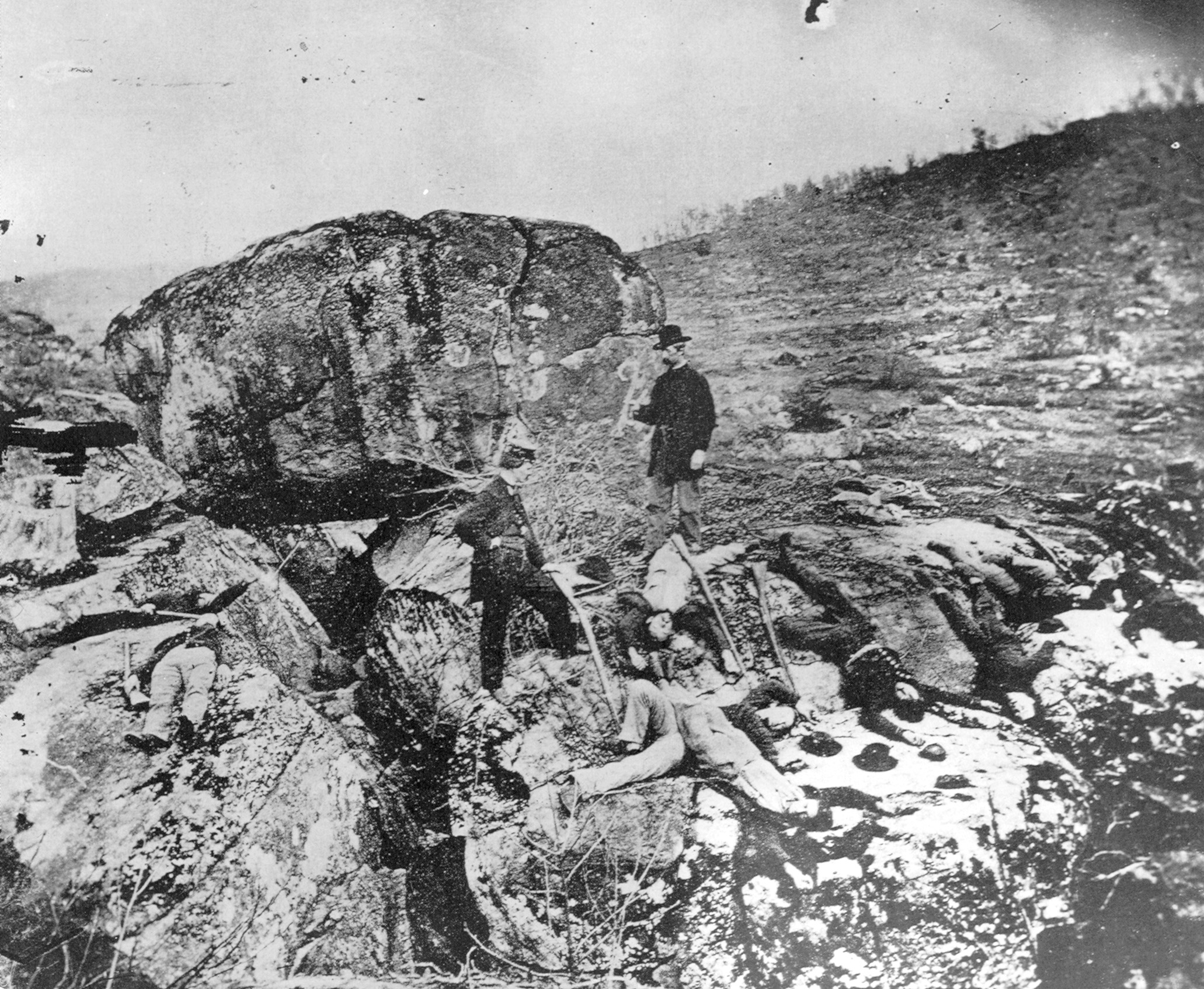

This sporadic picket firing prevented either side from burying their scattered dead comrades until long after the fighting ended. In some crevasses of the rocks and boulders bodies were piled three and four high. A large number of still-unburied corpses lying among the rocks was captured three days later in more than a dozen photographs by Washington photographer Alexander Gardner. They still testify to the ferocity and horror of the struggle.

Losses were heavy on both sides. The seven regiments of Ward’s Brigade that served in this sector suffered 732 casualties—almost half of their total strength. Among the worst hit were the 20th Indiana, 4th Maine, and the 40th New York from de Trobriand’s Brigade, each of which lost around 150 men. Another 110 men from the 99th Pennsylvania, 90 from the 124th New York, and 66 from the 86th New York were casualties. Ward also reported the loss of eight of his 14 field officers.

Union or Confederate Victory?

Confederate casualties were equally severe. Robertson’s Brigade, which had been engaged primarily on Houck’s Ridge and Devil’s Den, lost 597 men. Hardest hit was the 3rd Arkansas, which lost 142. Anderson’s Brigade took 671 casualties, while both Law’s and Benning’s Brigades each suffered about 500. Given the manner in which the various regiments of these other three brigades were shifted around on this portion of the field, it is difficult to determine how many men actually fell on Houck’s Ridge and among the boulders of Devil’s Den.

Who won the battle for Devil’s Den? Although the Confederates did gain control of this portion of the field, the defense of Houck’s Ridge and Devil’s Den was ably conducted by Ward and Smith. The Union forces held their ground in the face of superior numbers for more than an hour and a half, launching well-timed counterattacks that kept their adversaries off balance and unable to coordinate their efforts until their greater numbers finally told. No doubt the difficult terrain, dense clouds of powder smoke, and frequent barrage of well-aimed artillery fire aided the defense of this position as well.

The chief merit on the Federal side was that the soldiers there secured the left flank of the Union Army in time for Vincent’s V Corps to arrive and hold Little Round Top. Birney had nothing but praise for Ward’s Brigade, proudly stating that it “held also a post of great honor and importance, and fully sustained its old reputation.” Perhaps Ward’s words are even more appropriate in honoring the bravery of his small but resolute brigade that sacrificed so much for their country: “To the officers and men of my command, without exception … the thanks of the country are eminently due.”

Vincent’s V Corps?

I imagine you omitted the word “brigade” in that sentence as the Corps was commander by MG George Sykes that day at Gettysburg.

The holding of Devil’s Den for so long and the orderly withdrawal along with Col. Chamberlain’s Maine at Little Round Top broke Confederate momentum and played a large part in the Union victory. It had been Lee’s plan to achieve a “rolling assault” to overrun Union forces. These and other small area actions were effective in providing stumbling blocks to that plan.