By Sam McGowan

The most controversial decision of the 20th century—probably in all of history—was the one reportedly made by President Harry S. Truman, president of the United States and commander-in-chief of the United States armed forces, in the summer of 1945 to drop the atomic bomb on Japan. No other event has affected mankind so dramatically, and no other decision is as controversial.

To the young soldiers and Marines who were in training or moving to the Pacific when “the bomb” was dropped there was no question—many of them survived the war because Harry Truman “had the guts to drop it.” This belief was burned into their young minds when they heard the news and most never bothered to question whether it was founded on fact. In recent years their sons have sought to reinforce the belief of their fathers, once again without taking a serious look at the facts surrounding the decision to drop the bomb and the events leading up to it. Yet, in reality, Truman never made an actual decision to use the bomb, and it was the one decision made by Emperor Hirohito of Japan to accept Allied surrender terms and end the war that actually spared their lives.

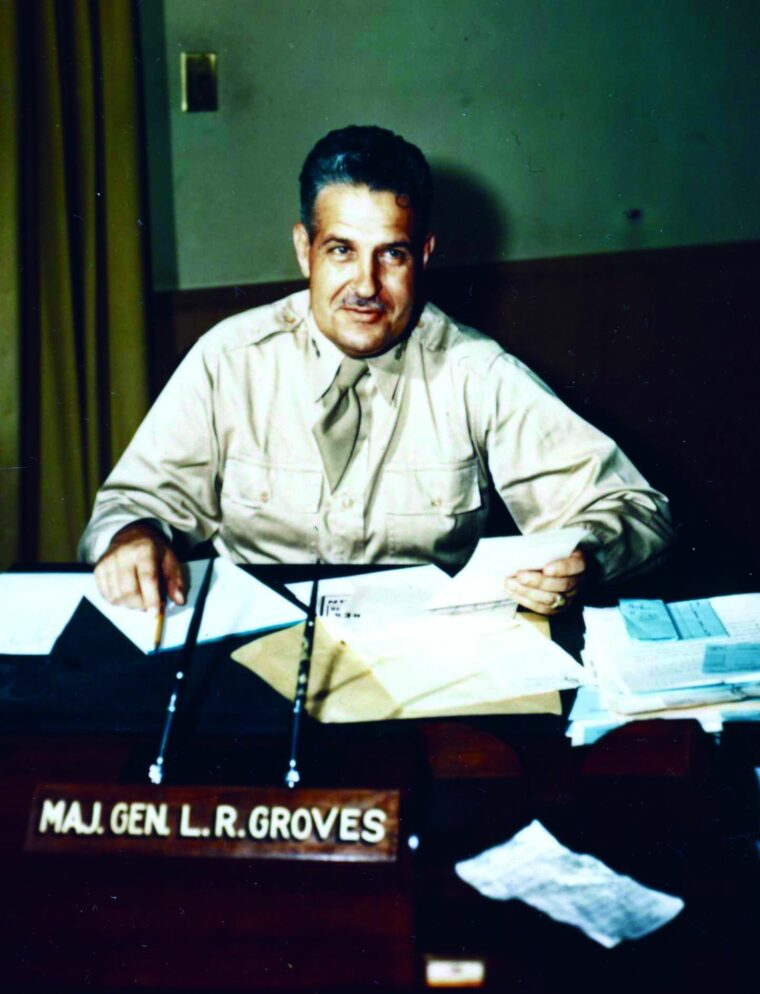

Even while millions of Americans continue to believe that the atomic bomb ended World War II, many, including some in high positions in government and the military at the time, have long believed it was unnecessary. Previously classified documents released to the National Archives in recent years support their position that the White House knew the end for Japan had already come and that the use of atomic weapons was motivated more by postwar concerns than by preventing an amphibious invasion of Japan. Furthermore, principals such as General Leslie Groves, the officer in charge of the nuclear project, have revealed that there never really was a “decision” as such by President Truman to drop the bomb, but that he simply allowed plans that were already in motion before he was thrust into office to continue. In essence, the decision to use atomic weapons against Japan was made long before Truman even had an inkling of their existence.

Building the Bomb

American research into the possibility of creating powerful weapons using nuclear fission actually predated the outbreak of World War II by several weeks. In July 1939, three European scientists met with renowned physicist Albert Einstein and persuaded him to write a letter to President Franklin D. Roosevelt advising that a bomb designed to produce a nuclear explosion might be under development in Germany. Einstein’s letter is dated August 2, 1939, nearly a month before Germany and the Soviet Union invaded Poland and World War II officially began. British scientists were already working on such a weapon, and the United States began a similar, although generally unsuccessful, effort in response to the Einstein letter.ƒ

In 1941, a group of American scientists visited England, where considerable nuclear research work was being done. Prior to the visit, no American scientist believed that nuclear fission would be of critical importance to the war, but the British work so impressed the visitors that in December they recommended that a full-scale nuclear project commence in the United States. President Roosevelt authorized a research program under the code name Manhattan Engineering Project, and British nuclear experts came to the United States to work with their American counterparts in research toward the development of a nuclear weapon.

In September 1942, the War Department assumed control of the project and Colonel Leslie R. Groves of the Army Corps of Engineers, who had previously been in charge of the construction of the Pentagon, was appointed as the project head. On December 2, 1942, Dr. Enrico Fermi, an Italian-born physicist working at the University of Chicago, achieved fission, the first controlled release of nuclear energy. Fermi’s successful experiment proved that it was indeed possible to develop a nuclear weapon and ushered the world into the nuclear age. The next step was to develop a means of maintaining the nuclear material in an inert state until the desired detonation point.

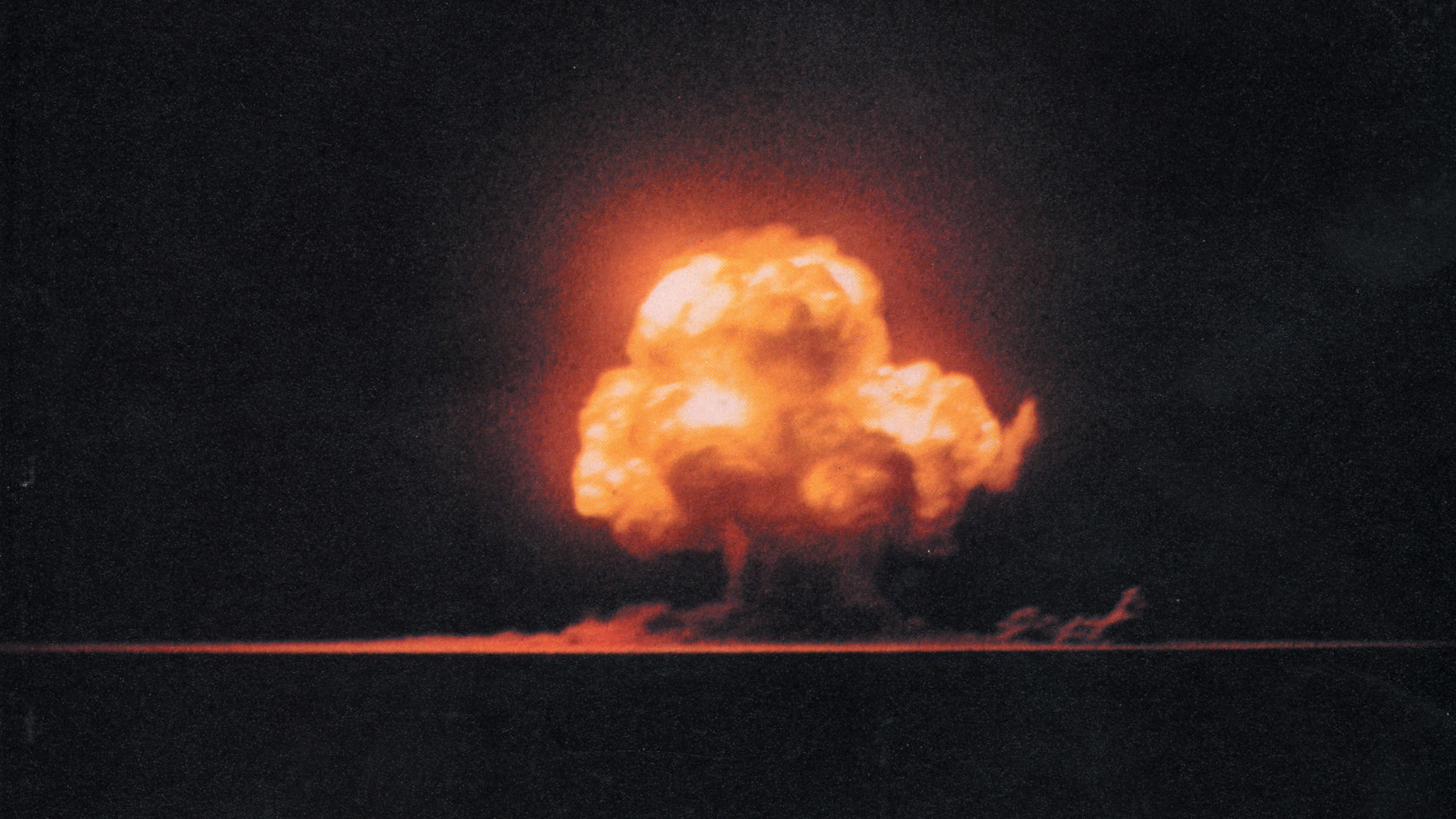

Manhattan Project scientists solved the problem by dividing nuclear material into two masses, then firing one into the other to achieve an explosion. Another method was to place the nuclear material between two masses of conventional explosives. The shock waves of their detonation would cause the plutonium to collapse and then expand again in a powerful explosion. The first method was used for the bomb dropped on Hiroshima, while the second was the mechanism for the first nuclear detonation at the Trinity site in New Mexico and in the bomb dropped on Nagasaki. The nuclear secret was so classified that President Roosevelt did not even inform his vice presidents of it. (Truman was the third of three vice presidents who served with Roosevelt. Truman was not elected until November 1944 and did not take the vice-presidential office until the following January, only a few weeks before FDR’s death.)

Finding a Suitable Delivery Vehicle

For any weapon to be effective it has to be delivered onto a target, and in the case of a nuclear weapon it has to be detonated in the air to achieve maximum effect. At the time, guided missiles did not exist and the artillery of the day lacked the range to deliver a nuclear warhead. The only option was delivery from the air in the form of an aerial bomb. In 1943, the only suitable delivery vehicle in the U.S. inventory was the Boeing B-29 Superfortress, a large, long-range, four-engine bomber that was under development at the same time as the bomb itself. Originally conceived in 1940, the B-29 had been planned for extremely long-range strategic bombing missions against Germany from bases in North Africa and the northern British Isles. The B-29 program was plagued with birthing problems, but planning for a special combat unit to deliver the new weapons when they were developed began even before the first Superfortress entered operational service.

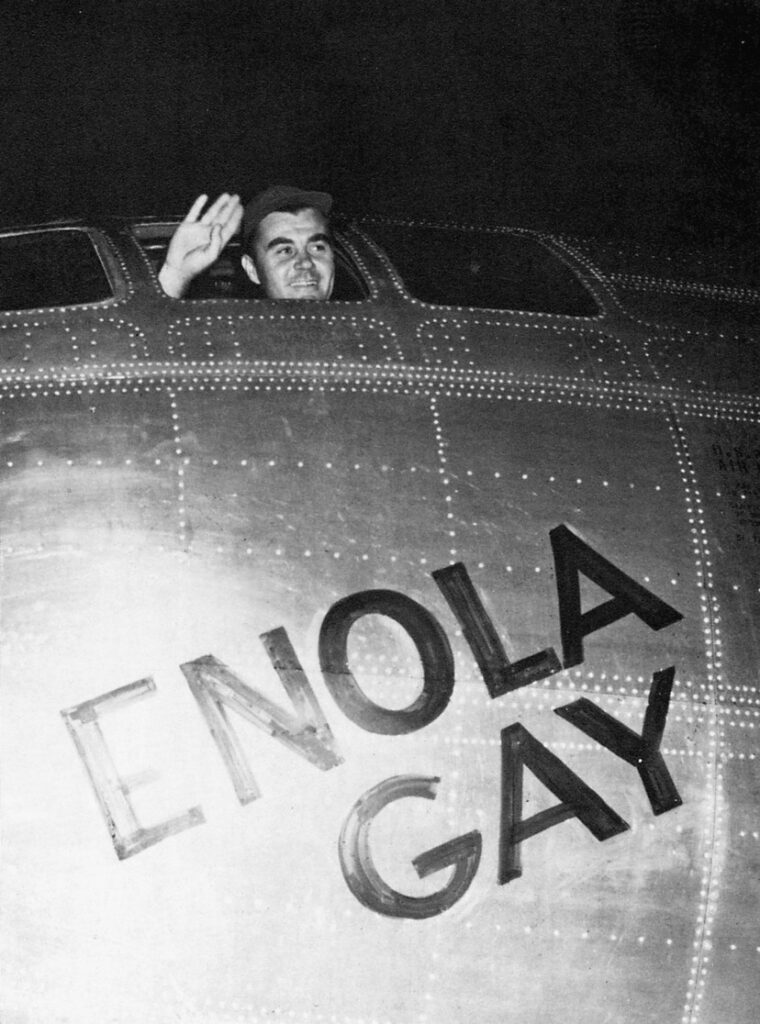

To command the new unit, which would be designated as the 509th Composite Group, Army Air Forces commander General Henry H. Arnold selected Colonel Paul W. Tibbets, Jr., a veteran bomber pilot from Columbus, Ohio, who had seen combat in Europe and North Africa but who had no experience against the Japanese. Lt. Col. Thomas J. Classen, a Pacific veteran who had been awarded the Distinguished Service Cross for a 1943 mission in a B-17 Flying Fortress bomber, was selected as his deputy. Classen was already in command of the 393rd Bombardment Squadron, the operational unit that would actually drop the nuclear device.

Tibbets picked most of his staff officers from members of his former group, while others were chosen because they had special qualifications that made them particularly useful. Only Tibbets himself was privy to the nuclear secret. The other members of the group knew only that when they went into combat, it would be to drop a special kind of bomb. They came to refer to the weapon they knew nothing about as “the gimmick.” Tibbets was in complete charge of organizing and staffing his new unit and with selecting the training base. He chose Wendover Field, a remote base in the Utah desert that had previously been used to train aerial gunners. Wendover’s remoteness was a major factor in Tibbets’s choice—he thought it would enhance security. The 393rd Bombardment Squadron, a B-29 squadron then in training at Fairmount, Nebraska, would be the combat element of his new command. The 509th Composite Group was activated in September 1944, and by the end of December the men of the 393rd had completed their training and were ready for combat. The question was—where?

1943: Japan Confirmed as the Target

Traditional atomic bomb lore records that the Manhattan Project was originally begun with the intent of using the weapon against Nazi Germany. Apparently, this is what the scientists working on the project, many of whom were Jews who had fled Europe, were led to believe. In January 1945, the War Department revealed that Hitler’s Germany was nowhere close to developing a nuclear bomb of its own and that the Germans were on the verge of defeat.

By this time some of the scientists involved in the project had begun to have second thoughts about the wisdom of actually using nuclear weapons. They had come to realize their awesome power and the possible implications for a future world. A number of Manhattan scientists signed a letter expressing their opposition to continuing development of the bomb because it was no longer needed to defeat Germany.

In reality, the bomb was never intended for use against Germany except, perhaps, during the first year or so of research. The Military Policy Committee, a high-level group—including Leslie Groves—that was set up to determine how best to use nuclear weapons, decided as early as May 5, 1943, that the proper target for such an awesome weapon was Japan. This decision was made more than two years before the first test of the new weapons. One possibility was the massive supply base at Truk, from which Japanese military operations in the Southwest Pacific were supplied. According to minutes of the May meeting, the Japanese were selected to be the recipients of the bomb because they “were less likely to secure knowledge from it as the Germans,” possibly in the event of a dud.

Tibbets, a retired U.S. Air Force brigadier general who died in 2007, has been quoted as saying that he was told that the unit would drop bombs on both Germany and Japan, but this is doubtful. The decision to use the bomb on Japan was already made long before it was close to reality and more than a year before Tibbets even knew it existed. Tibbets has revealed that he was briefed on the bomb by Colonel Edward Lansdale, an Army Air Corps officer who had close ties with the Office of Strategic Services (OSS) and its postwar successor, the CIA, and who evidently served as a kind of special projects officer with the War Department during the war.

The Allied Way of War

Japan was undoubtedly chosen to be the target for the bomb because of Allied policy regarding the Pacific War. In December 1941, only a few days after the attack on Pearl Harbor, President Roosevelt and British Prime Minister Winston Churchill decided on a Germany first policy for prosecuting the war. Under the policy, the full focus of the Allied war machine would be directed toward defeating the Nazis, who were considered a more serious threat than Japan, while maintaining a holding action in the Pacific. After Germany was defeated, the full power of the Allies would be redirected against Japan. The timetable agreed on by the senior Allied officials called for Japan not to be defeated until 1947 at the earliest, a gross underestimation as it turned out.

At the time of the decision to use the atomic bomb against Japan, the Allies had made only scant progress toward driving the Japanese northward. The battle for Guadalcanal had just ended, and Japanese forces still controlled much of New Guinea and most of the Solomons, while the U.S. Navy was recovering from its carrier losses at Coral Sea and Midway as the Pacific Fleet rebuilt. The use of such a powerful weapon against Japanese installations in the Pacific was seen as a means of holding the line and perhaps advancing. The military situation at the time made the possibility of using of a powerful new weapon against Japanese forces seem logical. A few weeks previously the White House had come out with a new policy that made the possibility of such a weapon even more attractive.

After the Casablanca Conference in January 1943, President Roosevelt revealed a new policy to the press. The new policy was “unconditional surrender,” a term that did not appear in the communiqué of the conference and that both Roosevelt and Churchill later denied was premeditated. The term was quickly picked up by the media and soon became a political byword, even though the implication did not set well with many Allied military leaders who believed that depriving the Axis nations of the opportunity to negotiate a surrender or truce would prolong the war and cause needless casualties. In essence, a policy of unconditional surrender left no latitude for any of the Axis nations to negotiate peace terms. It called for complete and total war against civilians as well as military forces. Roosevelt apparently conceived the idea, and Churchill grudgingly accepted it after the American president made it public.

Keeping the Communists in Check

The third member of the so-called Grand Alliance was Josef Stalin of the Soviet Union, a ruthless totalitarian dictator who basically could not have cared less about what Churchill and Roosevelt thought about anything. Chiang Kai-shek of China was the fourth major Allied leader, but his status was more of a courtesy than anything else. Chiang was not invited to most of the conferences and was usually kept in the dark about plans and policies made by the Big Three. In many respects, Stalin was as bad as and perhaps even worse than Hitler, and he had grand designs for Europe, if not the entire world.

Although the world remembers the Nazi invasion of Poland that started World War II, many often forget that Stalin’s Soviet troops invaded the country from the east in coordination with the German attack and set up an occupation force that was even more brutal than that of the Germans. Soviet troops rounded up thousands of Polish military officers and took them into the Katyn Forest where they were executed and their bodies dumped into trenches. Stalin switched his alliance—but not his allegiance—to the Allies only after Hitler broke their agreement and launched an invasion of the Soviet Union in the summer of 1941. When the Germans occupied eastern Poland, they discovered mass graves in the Katyn Forest holding the remains of more than 4,000 Polish officers, each with a single bullet in the head. When Germany revealed the massacre, President Roosevelt, who knew the truth, lied to the American public and blamed the atrocity on the Nazis to protect Stalin and the Soviet allies.

In the late summer of 1944, Stalin showed his true colors and revealed his designs for Europe. When the Polish Resistance rose against the Germans, Stalin halted his forces outside Warsaw and allowed the Poles to be slaughtered. In essence, Stalin allowed the Germans to do what he would have done himself once Soviet forces occupied the area. Stalin was a ruthless and wicked ruler, and many of the Allied politicians and military commanders realized this. To those who were aware of the nuclear secret, such power was seen as a means of keeping Stalin and the Soviet Communists in check in the postwar world.

Since the Manhattan Project was classified, President Roosevelt thought the Soviets were in the dark concerning the development of the atomic bomb. Intelligence sources would later reveal that the Soviets knew every detail of the project as it developed. Among the scientists working on the bomb were some with Communist leanings, and nuclear secrets were being smuggled through Red agents to Moscow, where Soviet scientists were doing their own nuclear research. It is likely that Stalin also was well aware that U.S. grand design included the use of nuclear weapons to defend against Soviet aggression after the war.

Closing in on the Home Islands

In 1945, the Allies were winning the war on all fronts. Although the Germans had launched a major counteroffensive in the Ardennes Forest the previous December, their advance had literally run out of fuel and the Allies were able to return to the offensive by the new year. Soviet troops were advancing toward Berlin from the east, and it was obvious that Hitler’s Third Reich was in its last days. There was also good news in the Pacific. Although the original Churchill-Roosevelt plan, with Stalin and the Soviets neutral in the war against Japan, had been to hold the line in the Pacific, Allied forces fighting on a shoestring had managed to defeat the Japanese in the Southwest Pacific and were advancing northward toward Japan.

American troops had landed on Luzon in the Philippines after first landing at Leyte in October. While land and air forces under the leadership of General Douglas MacArthur advanced through New Guinea toward the Philippines, Marines and soldiers serving under U.S. Navy command moved through the Solomon Islands, then northward in their assigned theater, the Central Pacific. By the end of 1943, the U.S. Navy had rebuilt from its early losses to become a powerful force. The massive Japanese depot at Truk came under air attack from carrier and land-based aircraft in early 1944 and was soon neutralized, thus eliminating it from the list of possible nuclear targets. In the summer of 1944, Central Pacific forces landed in the Marianas, securing land for the construction of air bases from which the new B-29s could launch air attacks on the Japanese Home Islands.

It is commonly believed that the Japanese intended to fight to the death, and although this may certainly have been true of the most radical of the Japanese militarists, it was not true of Japan’s civilian leadership and the population as a whole. Unlike Germany and Italy, Japan was not ruled by a dictator. Japan’s system of government was a monarchy, but the government was actually under the leadership of a prime minister, who in turn governed along with a cabinet made up of both military and civilians and a parliament known as the Diet. Furthermore, the Japanese population consisted of castes, with the militarists coming from the nobles while the rank and file were from the lower classes.

Prior to the Allied success at Saipan, the Home Islands of Japan had not been seriously threatened. Although the tide of war had turned in favor of the Allies in the Pacific, Allied victories had been in areas that had been occupied by Japan in early 1942. American bombers led by Lt. Col. Jimmy Doolittle struck Japan in April 1942, but this was a surprise attack launched from a single aircraft carrier and did little damage. As a result, Japanese forces in China went on the offensive and gained control of all areas of China from which Allied bombers could operate against Japan, thus sparing the Home Islands from air attack for more than two years.

With the exception of Guam, which was a U.S. possession, the Marianas were a different story. They were mandated to Japan by the League of Nations immediately after World War I and thus were Japanese territory. The loss of Saipan sent a message to Tokyo that Japan itself was threatened. Prime Minister Hideki Tojo, who had assumed the office in October 1941, was forced to resign, and a new cabinet was formed under Koiso Kuniaki, who, like Tojo, was a general in the Japanese Army.

First Strikes on Tokyo

The invasion of Saipan coincided with the commencement of an American air campaign against Japan, with the first mission directed at targets on Kyushu on the same day as the invasion. The attack was carried out by B-29s based in India and staging through advance bases in the vicinity of Chunking, China. Some of Japan’s industrial leaders said after the war that the first B-29 attack caused them to realize that the war was lost. Even though little damage was done to the target, the fact that the Allies were now in bomber range of the Home Islands was ample indication of the threat to Japan itself, a threat that was compounded by the knowledge that Saipan was close enough to Tokyo to allow attacks on the main island of Honshu and Japan’s industrialized areas around Tokyo Bay.

The country was also beginning to suffer as Allied aircraft and submarines began cutting the shipping lanes that brought raw materials and, more important, foodstuffs into Japan from the areas it had occupied elsewhere in the Pacific. Oil fields in the East Indies were still in Japanese hands, but the routes over which the tankers were obliged to sail to bring crude oil and petroleum to Japan were subject to constant attack.

The first strike on the Tokyo area occurred in late November 1944, when B-29s attacked aircraft manufacturing facilities at Mushasino. For the next several months attacks continued, although bombing results were far less than what the Allies had hoped. Initial B-29 operations against Japan were mostly daylight precision raids directed at manufacturing facilities related to the Japanese aircraft industry. Some attacks achieved better results than Allied intelligence indicated, but they would not be known until after the war when the Allies gained access to Japanese records.

In February, U.S. Marines landed on tiny Iwo Jima, a volcanic island 650 miles southeast of Tokyo. The island featured an airfield that served as a staging base for Japanese bombers on missions against the new American bases on Saipan, but the main purpose of the invasion was to secure an emergency landing field for crippled B-29s returning from raids over Japan and as a base for escort fighters and B-24 Liberators. U.S. intelligence underestimated the Japanese defenses, and the battle for Iwo Jima turned out to be one of the most intense in Marine Corps history. Although the Japanese defenders knew they were doomed, they determined to sell their lives dearly and kill as many Americans as possible in a last-ditch struggle. The resulting high number of Marine casualties led many Americans to believe that the same attitude prevailed among the Japanese population as a whole. But Japan itself had yet to be subjected to the most destructive attacks in human history.

The Air Campaign Comes in Full Force

The lack of success of the B-29 raids led the Twentieth Air Force, the U.S. Army Air Forces command element that controlled the long-range bombers, to try a change in tactics. Oriental construction methods depended largely on bamboo and even paper rather than steel and concrete, and Twentieth Air Force planners believed many structures were susceptible to incendiary attack. An incendiary raid against the Hankow docks in China in December 1944 produced spectacular results, effectively destroying the city as Japan’s main supply base in China. Test missions with incendiaries were flown against targets in Japan, but results were inconclusive and attacks continued with high explosives.

In early March XXI Bomber Command launched an incendiary mission against Tokyo, and the results left no doubt. The bombers were sent in at night at altitudes much lower than previous missions, so low that many of the crewmen thought they were suicidal. Guns, ammunition, and gunners were left off the B-29s to increase payloads, which consisted of napalm and incendiary bombs. Pathfinders went in ahead of the main force and dropped napalm to mark the target for the main force, which followed with incendiaries to spread the fires. The result of the raid was the most destructive event in human history. Winds whipped up by the fires produced a conflagration that destroyed a wide area of the city. The flames were so intense that water in the city’s canals boiled.

Japanese records revealed that 83,000 people were killed and 40,000 injured by the fires. Six firebombing missions were flown against targets around Tokyo Bay before the American landings on Okinawa led to a diversion of the B-29s to attack airfields on Kyushu. Casualties on Okinawa were again heavy as the Japanese defenders fought another stubborn battle designed to produce as many casualties as possible. The effect on morale in the United States was profound, but the loss of Okinawa had an even more profound effect on the Japanese. Once again, the Japanese cabinet was replaced. The new prime minister, Admiral Suzuki Kantaro, reported after the war that his instructions from Emperor Hirohito were to find a way to end the war as soon as possible.

As the battle for Okinawa concluded, the air campaign against Japan resumed with a vengeance. During the interim, hundreds of additional B-29s had arrived in the Marianas, allowing even larger formations for the firebombing. The B-29s were joined by smaller B-24s flying from Iwo Jima, and Liberators were soon operating from airfields on Okinawa and nearby Ie Shima as well. A second B-29 force was preparing to move to Okinawa.

U.S. Navy carrier aircraft were now free to attack targets in Japan, while Fifth Air Force fighter-bombers and light and medium bombers were striking Kyushu. Japan’s cities were literally being bombed into rubble, and the Japanese civilian leadership feared that unless the war was brought to an end soon the entire country would be destroyed. Not only that, the Home Islands had been isolated from their normal sources of food as U.S. submarines prowled Japanese waters, cutting sea arteries to the Asian mainland. Food and other commodities were in short supply, and the population was on the verge of starvation.

The Imperial Japanese Navy had been destroyed, and its air forces had been reduced to the point that they were capable only of kamikaze attacks owing to the lack of trained combat pilots and aircrews. Only the land forces on the islands were still intact, and they were made up of men with little combat experience who had been redeployed from Manchuria and Formosa as well as untried troops who had never left the Home Islands. The Army was depending to a large degree on civilians—including all women aged 16 to 40— who had been impressed into a home guard and equipped with primitive weapons. Civil defense had practically ceased to exist, with the only escape from the incessant air attacks for urban dwellers being to flee to the countryside.

Willing to Surrender

Although the Soviet Union, Britain, and the United States were allies in the struggle against Nazi Germany, Moscow maintained a neutral position in the war with Japan. When Germany attacked the Soviet Union in June 1941, Japan elected to stay out of the war. Similarly, when the United States asked Moscow for air bases in the Soviet Far East from which to bomb Japan, the Soviets refused the request, fearing that such an action would bring them into the Pacific War at a time when they were heavily engaged against the Germans.

As it became apparent to the Japanese that they would lose the war, Japan began sending peace offers to the United States via Moscow. Stalin, who had his own reasons for prolonging the war, elected not to pass the surrender offers on to Washington. Nevertheless, U.S. intercepts of messages made the United States aware of the offers. The messages were decoded and passed on to the highest levels of the U.S. government. Other indications of a Japanese willingness to surrender came in the form of messages sent through the Swiss embassy in Tokyo. When the Swiss ambassador to the United States made the surrender feelers known in Washington, he was told to ignore them and to inform his associates in Tokyo not to accept any more such messages.

While the soldiers, sailors, airmen, and Marines who were fighting the war were preparing to invade Japan and were fearful for their lives, America’s civilian leadership was well aware that the Japanese were on the verge of surrender, and many senior military officers believed that a costly land battle would be unnecessary. Senior officers who were not privy to the radio intercepts but were familiar with Japanese capabilities also believed that Japan would surrender without an invasion, especially if guarantees were given that the emperor would be allowed to retain his throne.

One officer who believed this was General Douglas MacArthur, the senior Army officer in the Pacific and the man who had been selected for command of all Pacific forces for the impending invasion. MacArthur, who had spent much of his life in the Orient and was well acquainted with Asian philosophy, is reported to have informed Washington of his views that Japan was on the verge of surrender as early as January 1945. It is known that his chief of staff for air, Lt. Gen. George C. Kenney, informed Army Chief of Staff General George C. Marshall and President Roosevelt that an invasion of Japan was possible at that time.

“Russia Was Our Enemy”

On April 12, 1945, Roosevelt died of a cerebral hemorrhage, and Vice President Harry S. Truman assumed the office of president. The former senator from Missouri had been in office little more than two months and knew very little about Roosevelt’s foreign policies. Roosevelt had not even informed him of the existence of the Manhattan Project, much less of how he intended to use the atomic bomb. As a member of the Missouri National Guard, Truman had served as a captain of artillery in World War I and had risen to the rank of colonel after the war. Shortly after his arrival in the Senate, he was placed in charge of a commission investigating defense purchases. He had come to view the professional military with disdain and believed that he knew as much or more about military strategy and tactics as the Annapolis men and West Pointers who were running the war.

Truman’s correspondence regarding the use of the bomb was classified for a period of 50 years and was declassified only in 1995. Truman apologists claimed for decades that the president refused to discuss surrender with the Japanese because the intercepted messages indicated that they were not unconditional—that the Japanese wanted the emperor to remain on the throne. Such, however, was not really the case. Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson wrote in his autobiography, “History might find that the United States, in its delay in stating its position on unconditional surrender terms, had prolonged the war.” Stimson did not state that the delay might have been due to the desire to demonstrate the power of the atomic bomb to the world, particularly the Soviets, even though he knew that was the reason. Former President Herbert Hoover wrote a letter to Truman admonishing him to make U.S. intentions regarding surrender clear. In his letter, Hoover stated that if the Japanese understood what the United States wanted they would surrender without an invasion and spare the lives of up to one million Americans.

General Groves added, “There was never from about two weeks from the time I took charge of this project any illusion on my part but that Russia was our enemy and the project was conducted on that basis.” Groves had taken charge of Manhattan Project in 1942.

In late 1944, Secretary of War Stimson stated, “Troubles with Russia were connected to the future of the atomic bomb.” Arthur Compton, one of the driving forces behind the bomb’s development, wrote to Stimson in response to criticism of the project from other scientists in early 1945: “If the bomb were not used in the present war, the world would have no adequate warning as to what to expect if war should break out again.” Comments such as these leave little doubt that the primary goal behind the development of the atomic bomb was to put the United States in a preeminent position in the postwar world, and that to demonstrate its power it was imperative for it to be used before hostilities ended.

Groves also wrote that there never really was a “decision” to use or not to use the bomb, but that its use was merely the continuation of a process that had already been set in motion. President Roosevelt had decided before his death that the bomb would be used against a Japanese target at the earliest opportunity and also decided that development of nuclear weapons would continue after the war. Roosevelt’s plans were a legacy that Truman merely continued. After the Allied victory in Europe, Air Corps General Carl Spaatz was sent to the Pacific to take command of the strategic bombing campaign against Japan. On the way, he stopped in the United States for briefings and a short leave. During his time in Washington, he was informed of the impending availability of the bomb and was told that as soon as it was available he was to use it. Spaatz, who had opposed American involvement in “terror bombing” in Europe, informed Generals Arnold and Marshall that before he would use such a terrible weapon he must have a written order instructing him to do so. An order instructing the 509th Composite Group to drop an atomic bomb “not later than August 10” was issued on July 25, 1945, nine days after the first successful test. A bomb was already on the way to the island of Tinian in the Marianas, where the 509th Composite Group was based. Truman wrote in his diary that evening that he had authorized the use of the most terrible weapon in human history “only against a military target, not against women and children.”

Did the Bombing Targets Hold Strategic Importance?

Years after the war, President Truman would claim that he had decided to use the bomb because he had been advised by General Marshall that an invasion of Japan would cost as many as a million American lives. Marshall made no such claim; the figure most likely came from the Hoover letter. Expected casualties from the initial invasion of Kyushu were a small fraction of that number. American combat deaths in the entire Asiatic Theater amounted to fewer than 93,000 men, roughly one-third of U.S. combat deaths for the entire war. Truman also claimed that he asked Secretary of War Stimson which Japanese cities were devoted exclusively to war production and was advised that Hiroshima and Nagasaki fell in this category.

In fact, neither was a major war production center, and Hiroshima had been taken off the existing target list, along with Kyoto, Niigata, and Kokuru, because they had been untouched as yet by the war and were identified by the War Policy Committee as suitable targets for the new weapon. As Japan’s eighth-largest city, Hiroshima’s main military significance was that the Second Army headquarters was located there. Although there was some war production there, the city was far less important than other metropolitan areas. Had Hiroshima been militarily important, it would not have been restricted from conventional attack.

Nagasaki had been attacked before and was actually selected by XXI Bomber Command chief General Curtis LeMay as an atomic target when Kyoto was stricken from the list by Secretary of War Stimson because of its cultural and religious significance. As a principal city on Kyushu, it might have been important in the impending invasion. Even then, however, Nagasaki was third on the list and was struck only because Kokuru was obscured by clouds and orders called for the bomb to be dropped visually rather than with radar.

Did the Bombs Have Any Effect?

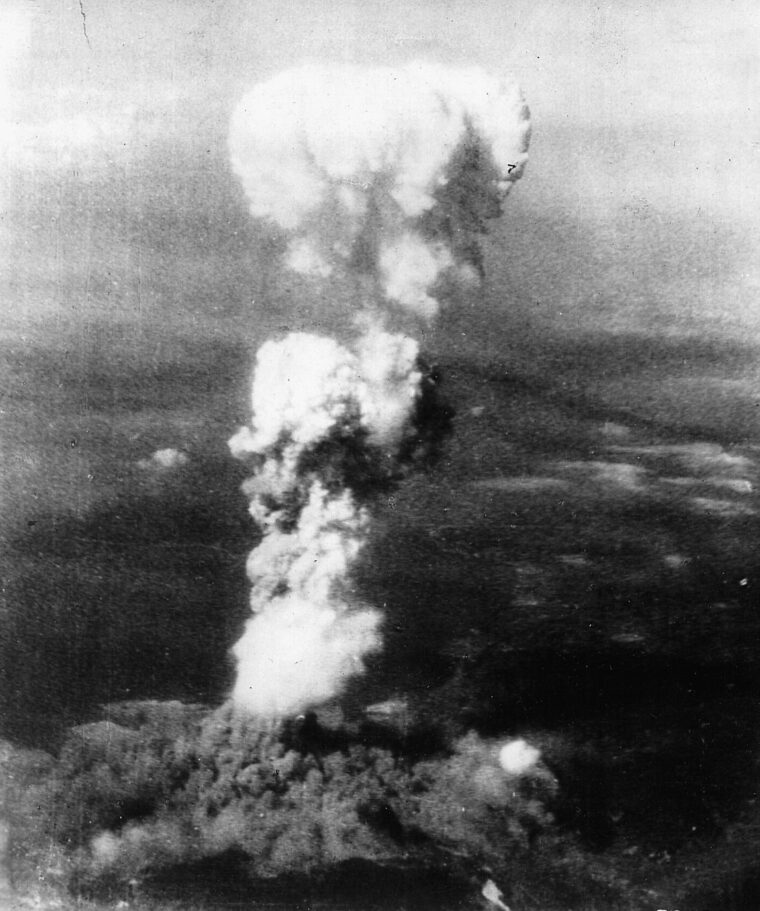

Remarkably, barely three weeks passed between the detonation of the Trinity weapon in New Mexico on July 16 and the appearance of the mushroom cloud in the skies over Hiroshima on August 6, 1945. There was no military urgency for such quick use. The battle for Okinawa had ended almost two months before, the Philippines campaign was in its mopping-up phase after the liberation of Manila in March, and the planned date for the invasion of Japan was still nearly three months in the future. Germany had surrendered, and the Pacific War had settled into a sort of lull while Allied forces built up for the planned invasion of Kyushu. In short, there was no justifiable reason for rushing the use of the atomic bomb—unless it was out of fear that Japan would surrender before it could be used.

As it was, the use of the atomic bomb against Hiroshima did not end the war. Nor did the second bomb, which was dropped on Nagasaki three days later. Only silence emitted from Japan in response. Casualties from the two bombs were great—more than 70,000 dead and missing at Hiroshima and at least 40,000 at Nagasaki—but no worse than those caused by the firebombing attacks on Tokyo and other Japanese cities. Although the morale in the two cities where the bombs were dropped was ruined, elsewhere in Japan news of the detonations had little effect. This was perhaps due to the considerable distances between the two atomic bomb targets and Tokyo. For that matter, the general morale of the Japanese people had already sunk to its lowest levels. After the war almost 70 percent of those interviewed by Allied intelligence said they had reached the point where they could not endure another day of war.

Meanwhile, the Japanese leaders were engaged in intense discussions. Emperor Hirohito had wanted to end the war that was destroying his country, and his desires were well known among the Japanese military and civilian leadership. The Japanese government had undergone a major shake-up in July 1944 when Tojo had been forced to resign after Saipan fell to the Allies. Since that time, there had been a rising peace movement within the Japanese government, but the military refused to consider any surrender terms that removed the emperor from his throne. A new government under Admiral Kantaro Suzuki, a former Navy chief of staff, was formed in April after the Allied invasion of Okinawa. Suzuki told interrogators after the war that the emperor had instructed him to seek peace but that he had been fearful of the militarists, who were not above assassination as a means of maintaining power and influence.

Hirohito Ends the War

The Allied Potsdam Declaration, which stated that if Japan did not surrender the nation would suffer complete and utter destruction, brought about a major debate among the Japanese leadership. Three of the leaders of the Supreme War Direction Counsel advocated immediate acceptance of the Potsdam terms, but the other three were opposed on the basis that demands were made to treat Japanese leaders as war criminals and there was no guarantee that the emperor would remain on the throne.

Hirohito was willing to accept the Potsdam demands issued on July 26 (almost two weeks before Hiroshima) as written but was unable to impose his will. Finally, two days after the detonation of the bomb over Nagasaki, Suzuki asked Hirohito to decide the issue in an Imperial Conference, a heretofore unprecedented act as the emperor’s traditional role was to approve or disapprove plans put forth by civilian and military leaders but not to advocate decisions himself.

Hirohito decided to accept the Allies’ terms, but to satisfy the militarists the Japanese surrender offer was conditional in that Japan would accept only if the emperor’s safety and continuation on the throne were guaranteed. Secretary of State James Byrnes recommended that the offer be accepted, and assurances were sent to Japan. On August 14, Hirohito informed the Japanese public of the surrender in his first-ever radio address to the nation. In the end, it was Hirohito, not Harry Truman, who made the decision that ended the war and avoided an invasion that could have cost thousands of lives.

The Atomic Bombs: A Mistaken Legacy?

When news of the Japanese surrender reached the world, Americans automatically and naturally assumed it was due to the detonation of the atomic bombs. Hundreds of thousands of soldiers, sailors, Marines, and airmen who were making preparations for an invasion believed that the atomic bomb had spared their lives. Because they were not privy to the information available at the highest levels of government, they had no idea that the Japanese had attempted to convey their wishes to surrender several months before the detonation of the bomb.

In contrast, many U.S. leaders, particularly those closest to the fight against Japan, believed the use of the atomic bomb was unnecessary, that Japan was on the verge of surrender without it. Immediately after the cessation of hostilities, members of the United States Strategic Bombing Survey entered Japan and began a systematic survey of the Japanese cities that had been the targets. The survey concluded that even without the two bombs “air supremacy over Japan could have exerted sufficient pressure to bring about unconditional surrender and obviate the need for invasion, probably by November 1, certainly by the end of December 1945.”

Author Sam McGowan is a licensed pilot and a resident of Missouri City, Texas. He is a frequent contributor to WWII History Magazine.

I am constantly amazed how many people try to rewrite history and consider the United States as a nation willing to use the Atomic Bomb on Japan for racial or cold War reasons. The Japanese had already proven that they were capable of very barbaric treatment of everyone, including their own people. The majority of people at the time believed them capable of fighting to the end with no surrender. The overwhelming evidence was that they would fight harder as we got closer to the homeland. They had absolutely no respect for soldiers who surrendered, and had plans to execute pows before they could be rescued. Their cultural was death or suicide was preferred to surrender. I have talked to many soldiers who served in WW2 and they all believe that the Atomic Bombs saved their lives. I have read alot of history and I put this in the same category as the bombing of Pearl Harbor was allowed to happen.

LTC SteveWeide (RET)

Very true, SteveWeide

Was it right for the Japanese to bomb Pearl Harbor on a Sunday morning without a declaration of war first? Was the use of thousands of chinese pows to test germ warfare acceptable? Was the Bataan Death March “Okay”? I wonder if any of the Deathcamp survivors ever questioned the morality of what we did? James Staley.

The bombing of Nagasaki was almost certainly unwarranted. It was a secondary target of no military significance. The logical target would have been the naval base at Sasebo, if for no other reason that it would have demonstrated to the rest of the world a certain moral discretion.

So, why would any country choose to use the lives on thousands of its young men to avoid killing the enemy? All the bleeding heart academics don’t have to go out and land under fire on the beaches.

I don’t do revisionist history, am 100% with Steve Weide. Nagasaki had over 25,000 troops in the city, plus weapons production facilities. Believe any large Japanese city was a military target, every city had war/war-related industries/facilities. Our path to Japan was paved with American blood, starting with Guadalcanal. No reason to think fighting in Japan itself would be any different. America was tired of the war, tired of seeing their sons and daughters killed. Any President who DIDN’T use the atomic bomb on Japan would have been impeached. As it was, using the nukes saved many, many more lives, both American and Japanese, than were taken. Sasebo has been a US Navy base since 1946, these days also shared with the Japanese Maritime Self-Defense Force.

I recall when the war started and ended. A neighbor didn’t come home, my cousin died on Iwo Jima. The Jap. military was cruel beyond description. The Japs. did execute many thousands of Allied P O W’s and ordered that if Japan was invaded all Allied P O W were to be murdered.

The author’s point that maybe we used the bomb to show the world how terrible the weapon is, if so, so be it. The people who oppose the bomb’s use are; they were not there or have not done extensive research and reading of the horrors of war.

As a nation we need to walk softly and carry a big stick!

David Seeds, Earleton, Fl.