By Frank Johnson

Five years after Great Britain had launched HMS Argus, the world’s first aircraft carrier, in 1917, and following the signing of the Washington Naval Treaty on February 6, 1922, the U.S. Navy Department ordered the conversion of a fleet collier, the 11,050-ton USS Jupiter. Commissioned in 1913, the collier had the Navy’s first turbo-electric powerplant, was the first American naval vessel to transit the Panama Canal in October 1914, and ferried a naval aviation unit to France in June 1917. Now, the Jupiter was designated to become the carrier USS Langley (CV-1), named for Samuel Pierpoint Langley, the famous 19th-century astronomer, physicist, and aviation pioneer.

While the collier was being converted at the Norfolk Navy Yard in Virginia through the spring and summer of 1922, Lt. Cmdr. Godfrey de Courcelles “Chevy” Chevalier led 15 pilots in flight training to operate from the Langley. They made touch-and-go landings on a 100-foot wooden platform laid on a coal barge. At the same time, Navy pilots trained on an 836-foot wooden flight deck at North Island, San Diego, California.

Commissioned on March 20, 1922, the nation’s first carrier was designed to carry up to 34 airplanes—12 single-seater “chasing” planes, a dozen two-seater “spotters,” four “torpedo-dropping” aircraft, and six “80-knot torpedo seaplanes.” The vessel’s first skipper, Commander Kenneth Whiting, was assigned, and the conversion work was completed in September 1922. She left for her shakedown cruise that month.

The Langley resembled HMS Argus—ungainly and with twin funnels that could be swung down during flight operations. Supported by steel box girders, the former collier’s 536-foot wooden flight deck covered her yawning holds, which still contained coal-dust particles when she was sunk two decades later.

Her arresting gear—cables stretched across the flight deck to grab the tailhooks of planes —later became standard equipment on all flattops. She was also fitted with a forward flush-deck catapult for launching aircraft when there was no wind over her deck. Commander Whiting and Captain (later Rear Admiral) Joseph Mason “Bull” Reeves, who commanded all fleet aircraft, developed other pioneering innovations for the Langley and later carriers.

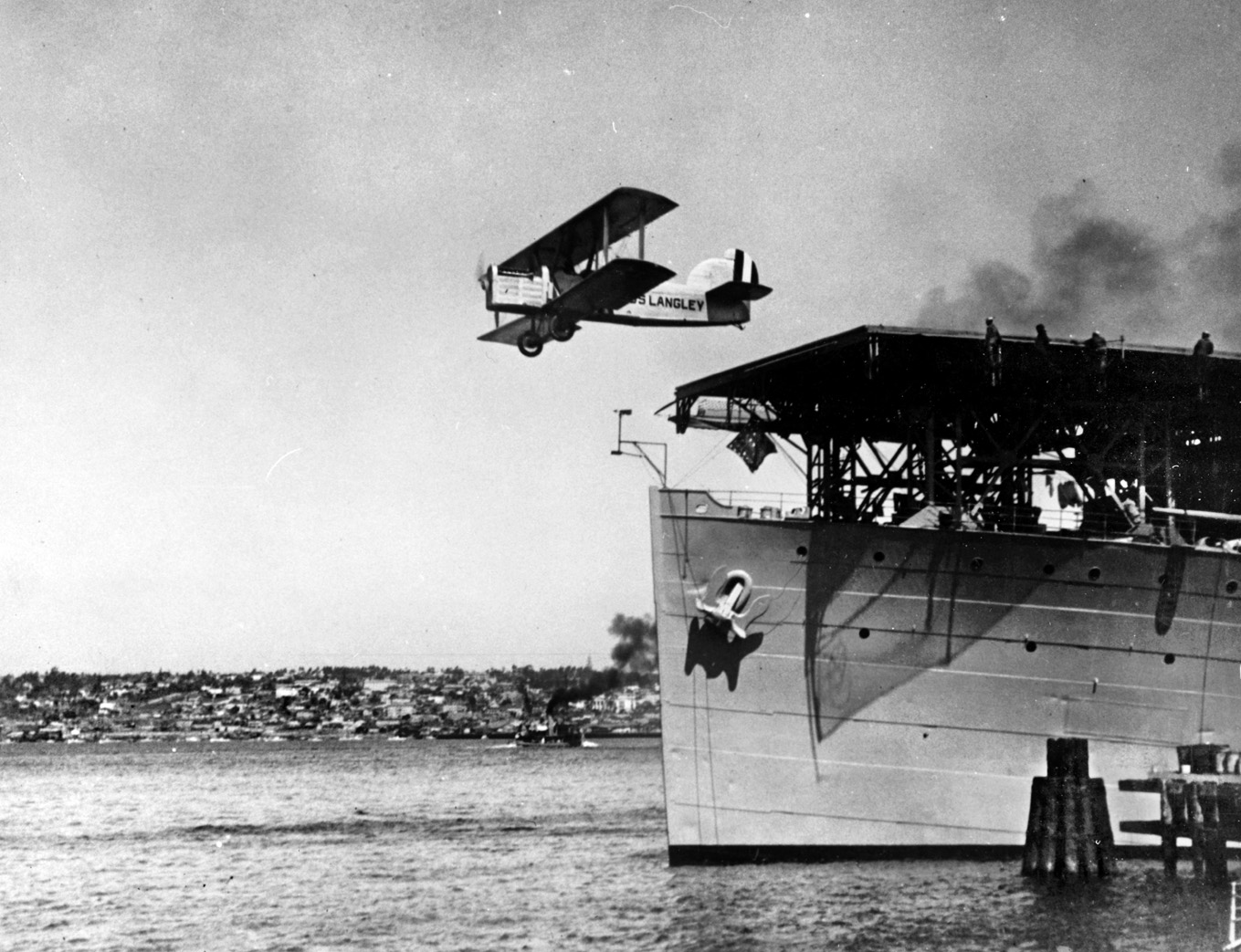

Much naval history was made aboard her, starting on October 17, 1922, while she was anchored in the York River, a Chesapeake Bay estuary. On that day, Lt. Cmdr. Virgil C. Griffin made the first takeoff from her flight deck in a flimsy Vought VE-7SF biplane. Nine days later, on October 26, while the Langley steamed off Cape Henry, Virginia, Lt. Cmdr. Chevalier landed his Aeromarine 39B biplane on the deck. The wooden propeller broke, but he touched down safely. Less than a month later, Chevalier died in a plane crash near Norfolk. Another landmark aboard the Langley came on November 18, 1922, when Commander Whiting made the first catapult launching.

For two crucial years, the first American flattop operated as an experimental ship: testing aircraft and flight deck equipment, developing takeoff and landing techniques, and training pilots. There were a number of accidents, but no fatalities. The Langley was the cradle of U.S. naval aviation, and many of her young fliers went on to flag rank and distinction, such as Lieutenants DeWitt C. Ramsey, John Dale Price, Gerald F. Bogan, Thomas H. Moorer, and Marc A. “Pete” Mitscher, who led the fast carrier task forces in the Pacific theater in 1942-45.

The naval air arm grew in the 1920s as the building of two more carriers – the Lexington and Saratoga – was authorized. On November 29, 1924, the Langley joined the Navy Battle Fleet at San Diego, and Fighting Squadron VF-2 began flying a dozen VE-7S biplanes from her for carrier qualifications in January 1925. This was the first squadron assigned to an American carrier, along with liaison planes and trainers. The Langley became the first flattop to participate in fleet exercises that March, and she chalked up a further landmark when Lt. Cmdr. Price made the first night landing on April 1, 1925.

That year, a bright young Naval War College graduate from Texas, Commander Chester W. Nimitz, played a groundbreaking role in successfully integrating the Navy’s lone carrier into a circular fleet formation. Admiral Samuel S. Robison, commander of the Battle Fleet, was impressed. Nimitz, who eventually reached fleet admiral rank and skillfully led the Pacific Fleet in World War II, reported, “I regard the tactical exercises that we had at that time as laying the groundwork for the cruising formations that we used in World War II in the carrier air groups and practically every kind of task force that went out.”

Captain Reeves, the gaunt, bearded Battle Fleet air commander, went aboard the Langley in October 1925, and, seeking to fill every square foot of deck space, increased her complement of planes. Her flight deck was lengthened by 23 feet during an overhaul at the Mare Island Navy Yard in California, and Reeves, now a rear admiral and the first Navy aviation officer to reach flag rank, ordered two full squadrons (36 aircraft) to be placed aboard. Six more planes were stowed below decks.

It was during 1925 maneuvers that the Navy led the way with dive-bombing techniques. Aboard the Langley, Reeves and Lt. Cmdr. Frank W. “Spig” Wead developed tactics to support troops in amphibious landings and for attacking enemy ships. The planes would approach targets at 10,000 feet and then dive at angles of up to 70 degrees.

Like Reeves, who eventually became the U.S. Fleet commander, Wead was a prominent pioneer in naval aviation. He led the first seven planes off the Langley’s deck in a record-breaking 41 seconds, tested and raced planes for the Navy, and held five world records in naval aviation. Wead was tireless in his efforts to gain public and congressional support for naval aviation.

In October 1926, Lt. Cmdr. Frank D. Wagner led Curtiss F6C-2 planes of Fighting Squadron 2 in a simulated attack on the Battle Fleet off San Pedro, California. Diving from 12,000 feet at an almost vertical angle, the Langley squadron “achieved complete surprise and so impressed fleet and ship commanders with the effectiveness of their spectacular approach that there was unanimous agreement that such an attack would succeed over any defense.” The Navy’s dive-bombing tactics soon received close study by the Imperial Japanese Navy and the German Ministry of Aviation.

Equipped now with Boeing F2B-1 fighters, the Langley took part in Army-Navy exercises off Hawaii in April-May 1928. She was able to operate 36 planes and could launch 35 aircraft in only seven minutes. The maneuverable Navy planes easily outfought the Army fighters, and an early morning “attack” with simulated bombing and strafing runs took the Army defenders by surprise. (A similar series of maneuvers proved successful in making Japan’s surprise attacks on the island of Oahu 13 years later.) It was because of her station during the 1928 war games that the Langley acquired her nickname. Thinking that she resembled the chuck wagon in a western cattle drive, the crew affectionately christened her the “Covered Wagon.”

The Langley again made U.S. naval history on July 30, 1935, when Lieutenant Frank Akers, piloting an OJ-2 spotter plane and using only instruments, executed a successful blind landing on her flight deck. But time was running out for the Covered Wagon, as larger and more powerful flattops joined the fleet. Converted from unfinished battlecruisers, the Saratoga and Lexington had been commissioned in November 1927; the USS Ranger, the first built-for-the-purpose carrier, was commissioned in June 1934, and the Wasp, Yorktown, Enterprise, and Hornet were also laid down.

Strategic thinking in the Navy Department was undergoing a transformation as the potential of military aviation became evident. Although many battleships were to play key bombardment, escort, and other support roles in the coming world war, their traditional ranking as capital ships was waning. Fleets would be centered instead around aircraft carriers, as with the U.S. Navy in the Pacific and the British Royal Navy in the Mediterranean.

The venerable Langley, meanwhile, had played a vital role while serving as midwife during the birth of American naval aviation. But the new flattops coming off the ways rendered her obsolete, so she was relegated to a less glamorous role as an auxiliary vessel. Between October 1936 and February 1937, she was converted to a seaplane tender at the Mare Island Yard. She lost the forward section of her flight deck and was modified to accommodate two squadrons of Consolidated PBY Catalina flying boats. She then operated in the Pacific and Atlantic until sailing westward to service Asiatic Fleet seaplanes. The Langley arrived in Manila on September 24, 1939, three weeks after the outbreak of World War II.

At the Cavite Navy Yard in the Philippines the following year, four three-inch antiaircraft guns were mounted on the flight deck of the Langley. She also was armed with four .50-caliber, water-cooled machine guns and a few automatic rifles for air defense. Her main battery of four five-inch guns mounted forward and aft, and which had survived the conversion, could not be used against aircraft.

When Japanese carrier planes savaged the U.S. Pacific Fleet at Pearl Harbor on Sunday, December 7, 1941, and thrust America into the war, the tender was anchored off Sangley Point in Manila Bay. Under cover of darkness, she departed on the night of December 8 and fled southward with two fleet oilers, the Pecos and Trinity. As Japanese invasion fleets closed in on the Philippines, the three vessels headed for safety in Australian waters.

During the voyage, the Langley provided support to PBYs while the USS Pecos refueled ships of the Asiatic Fleet. In the Sulu Sea, two Japanese torpedoes passed close to the tender, and her crewmen sighted enemy cruisers and destroyers. But she steamed on, undetected, and reached Darwin on the northwestern Australian coast on January 1, 1942.

There was little work for the Langley at Darwin in the grim early weeks of 1942, as makeshift American, British, Dutch, and Australian naval units fought a hopeless delaying action against the enemy in the waters around the Philippines and the Dutch East Indies. Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress bombers and Curtiss P-40 Warhawk fighters were sent north from Australia to join the Allied effort, and Japanese landings in the East Indies were imminent.

But the Langley was about to be assigned a vital mission. Early in February 1942, it was decided that she should carry much-needed fighters to Java to bolster its sparse defenses. Many planes, mostly flown by inexperienced pilots, had been lost in long, over-water flights, and the island of Timor, used for ferrying, was soon to fall to the enemy.

The Langley steamed to the port of Fremantle on the southwestern Australian coast, and 32 Curtiss P-40E Warhawks were loaded on her chopped-off flight deck and aft of the bridge on the main deck. The planes’ machine guns were loaded, but they were not fueled. Thirty-three pilots and a dozen enlisted mechanics went aboard. With one exception, the pilots had little or no experience in P-40s, though they had flown the 2,400 miles across Australia to reach Fremantle.

In addition, 27 crated Warhawks were loaded aboard the American-flagged freighter Sea Witch. Escorted by the USS Phoenix, the two ships headed out from Fremantle on February 22. Because of the pressing need for fighters in Java, the Langley and Sea Witch broke away and steamed—separately and un-escorted—for Tjilatjap, the only port where they could deliver their cargoes safely. Conning his vessel at 14 knots, her full speed, Commander McConnell planned to reach landfall early on February 27.

But the Langley was delayed on February 26 because of confusion over which ships would escort her on the last leg of the voyage. The Dutch minelayer Willem van der Zaan was assigned, but she could make only 10 knots because of a boiler problem. Finally, the U.S. destroyers Edsall and Whipple went out to meet the Langley, but there was another delay while they broke off to run down a suspected submarine contact. It was not until early on Feb. 27 that the tender and the destroyers were able to begin the final 100-mile run to Tjilatjap.

At 9 a.m that morning, an unidentified plane was sighted high above the three ships. Commander McConnell requested fighter cover from Admiral Glassford, but none could be spared by the hard-pressed U.S. Army Air Force squadrons on Java. When more planes were seaplane spotted at 11:40 a.m., the three ships raised their antiaircraft guns. McConnell sounded general quarters and signaled his plight to Java. The Langley and her escorts had been sighted by a patrol plane of the shore-based Japanese 11th Air Fleet, which had been keeping a close watch on Allied movements around Java.

At an altitude of 15,000 feet, nine twin-engine enemy bombers soon approached the three American ships. The Langley opened fire as soon as the raiders came within range. As the bombers glided in at an 80-degree angle to make their first pass, Commander McConnell ordered hard right rudder, and the bombs splashed harmlessly about 100 feet to port. Expertly maneuvering his tender, the skipper then foiled a second pass by the planes.

But the enemy did not give up, and the Langley’s luck ran out as the Japanese pilots anticipated her desperate maneuvering. The bombers came in a third time and badly damaged the 29-year-old ship with five direct hits and two near-misses. She reeled under the blows and started listing 10 degrees to starboard.

One after another, the P-40s lashed on her abbreviated flight deck burst into flames, fanned by a stiff wind. The steering mechanism and gyrocompass on the tender’s bridge were destroyed. As the burning Langley staggered along, six Zero fighters zoomed in to strafe her, but they soon made off.

Despite the chaos, McConnell tried gallantly to save the stricken vessel. He maneuvered in a bid to reduce the windage and control the fires, but this was unsuccessful. He ordered the burning planes to be pushed over the side and called for counterflooding to lessen the list. Realizing that the Langley could no longer negotiate the narrow mouth of the distant Tjilatjap harbor, he laid a direct course to the Java shore. He hoped to ground the vessel and save the few remaining P-40s, but inrushing water flooded both main engines and the electric propulsion system. The tender did not have damage-control equipment, and her pumps could not cope with the flooding. She lost all forward motion.

When the skipper gave an order to “make ready boats and rafts for lowering,” some crewmen misinterpreted it and jumped overboard. With the crippled tender dead in the water, McConnell had little choice. At 1:32 p.m., while the two destroyers were nearby and available to take off his crew, he gave the order to abandon ship. In the tender’s transmission room, the chief radioman ruefully tapped out a final message to the outside world: “Mama said there would be days like this. She must have known.”

All but 16 of the Langley crew and aviation personnel were rescued by the Edsall and Whipple. When Commander McConnell and his aides determined that only the dead were left in the smoldering tender, she was scuttled. The Whipple sank her with two torpedoes and nine rounds of four-inch gunfire. The proud old Langley went down 74 miles south of Tjilatjap. It was a gallant end to a naval era.

With better luck, the Langley might have gotten through. Lt. Cmdr. Hatfield’s Sea Witch was more fortunate. Dropping her anchor at Tjilatjap on the morning of February 28, she unloaded her crated Warhawks, took on 40 American refugee soldiers, and managed to steam back to Australia undetected by the enemy. The P-40s were assembled, meanwhile, but never saw action. They were destroyed by Army Air Forces personnel as the Japanese overran Java.

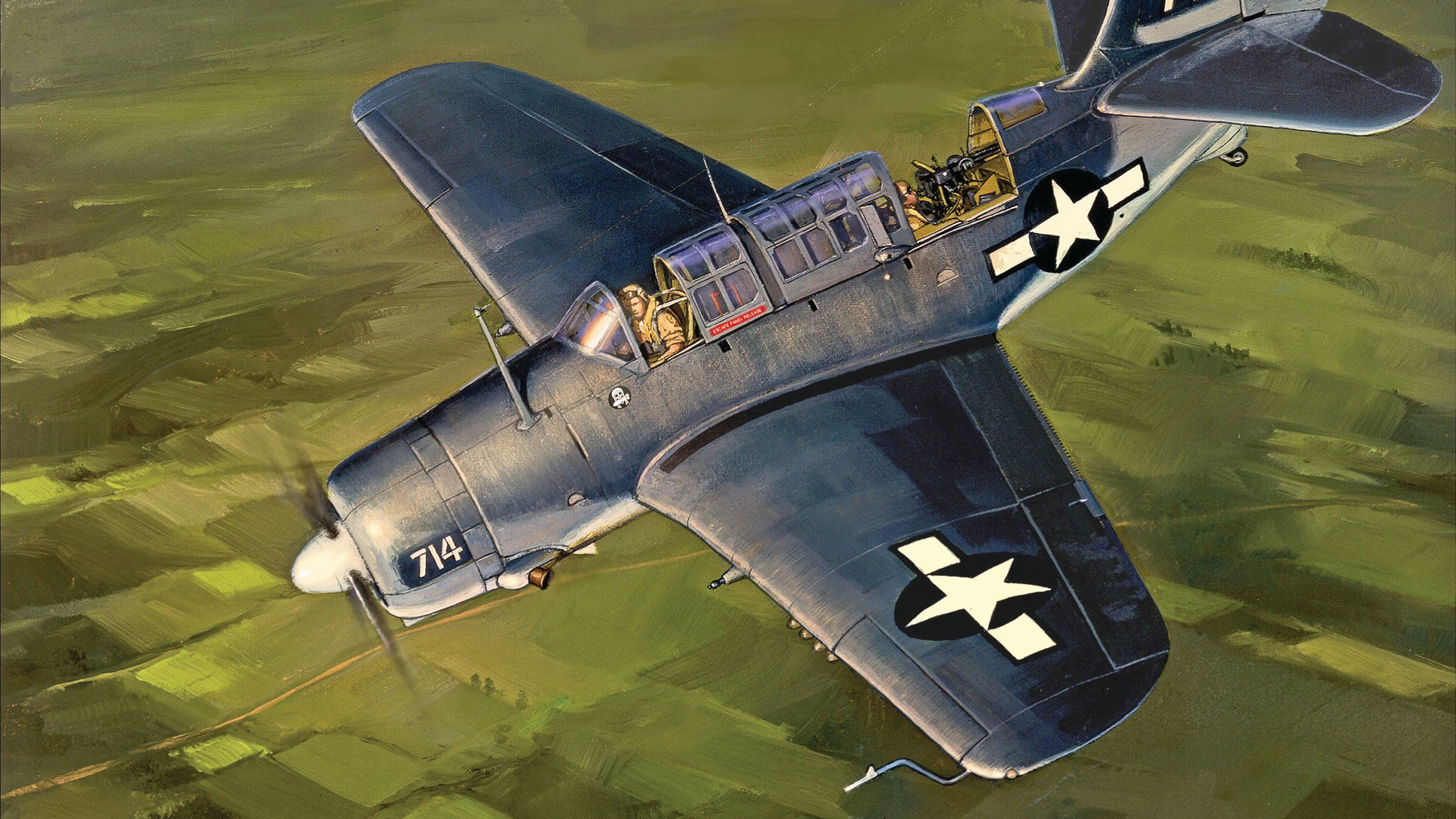

Misfortune continued to befall other American vessels around Java. On February 28, the last Allied warship north of Java was destroyed by a dozen Japanese Val and Kate carrier planes. Attempting to escape from the Java Sea, the destroyer USS Pope was battered into a drifting hulk and finished off by gunfire from enemy cruisers.

Around 9:45 a.m. on March 1, a plane from the Japanese striking force encountered the oiler USS Pecos off Christmas Island, southwest of Java. She had taken on board Langley survivors from the destroyers Edsall and Whipple earlier that morning. Two hours after the sighting, planes from the carrier Soryu swept down and sank the helpless oiler. That night, the Whipple located 232 survivors of the Pecos, many of them Langley sailors. Nearby, enemy battleships, cruisers, and two bombers from the Soryu ambushed and sank the USS Edsall. Her five survivors died while prisoners of war. The Whipple managed to escape to Australia.

The American, British, Dutch, and Australian ships of the doomed ABDA Command had fought hard against overwhelming odds, but the enemy closed in on the East Indies. On March 5, four Japanese carriers sent 149 bombers and fighters against Tjilatjap, and they sank 20 ships, mostly merchantmen. With the enemy now in virtual control of Java, Japanese soldiers marched into the port on March 8. The Dutch government had been evacuated, and the island’s commander, Gen. Hein Ter Poorten, agreed to surrender 100,000 Dutch, American, British, and Australian troops.

Along with many other Allied ships, the USS Langley had gone down fighting in the desperate early months of 1942, but her name was to live on as the Allies regrouped, grew stronger, and eventually took the offensive in the Far East.

Construction started in August 1942 on a second USS Langley (CVL-27), one of nine escort carriers of the Independence class. She displaced 10,600 tons, was 600 feet long, and was designed to carry a small air group of 32 to 34 aircraft. Her complement was 1,400. She was completed in July 1943, and was commissioned the following month.

The new Langley saw plenty of action with the U.S. Navy’s powerful task groups in the Pacific theater. After taking part in offensive operations around the Marshall, Palau, and Mariana Islands in October 1943, the Langley joined Rear Admiral Samuel P. Ginder’s Task Group 58.4, part of grizzled Rear Admiral Mitscher’s hard-hitting Task Force 58, in January 1944. From then until April 1945, the ship fought in more actions off the Marshalls, Leyte, the liberation of the Philippines, the invasion of Okinawa, and raids against the Japanese home islands. The Langley sailed with Vice Admiral John S. McCain’s Task Force 38 in the waning months of the Pacific War, surviving typhoons and damage from kamikaze suicide bombers off Formosa.

After the defeat of Japan and the end of World War II, more service awaited the Langley as French forces battled Communists in Indochina. The flattop was loaned to France in June 1951. Renamed the LaFayette, she launched sorties by Grumman Hellcat fighters and Curtiss Helldiver dive bombers in support of French Navy units in the South China Sea and the Gulf of Tonkin. The carrier was returned to the United States in 1963 and was scrapped the following year. Like her famous predecessor, she had fought gallantly in the continuing struggle against tyranny.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments