By Christopher Miskimon

May 1942 was a dark time for Colonel Nicoll F. “Nick” Galbraith and his fellow American soldiers in the Philippine Islands. The war was six months old, and so far it seemed things were going the way of the Japanese. Much of the U.S. fleet was sunk or out of commission following the Pearl Harbor attack on December 7, 1941; what was left was busily fighting defensive actions, unable to achieve a relief of the American-Filipino force struggling to hold off the invading Japanese. The troops in the Philippines were left almost entirely on their own.

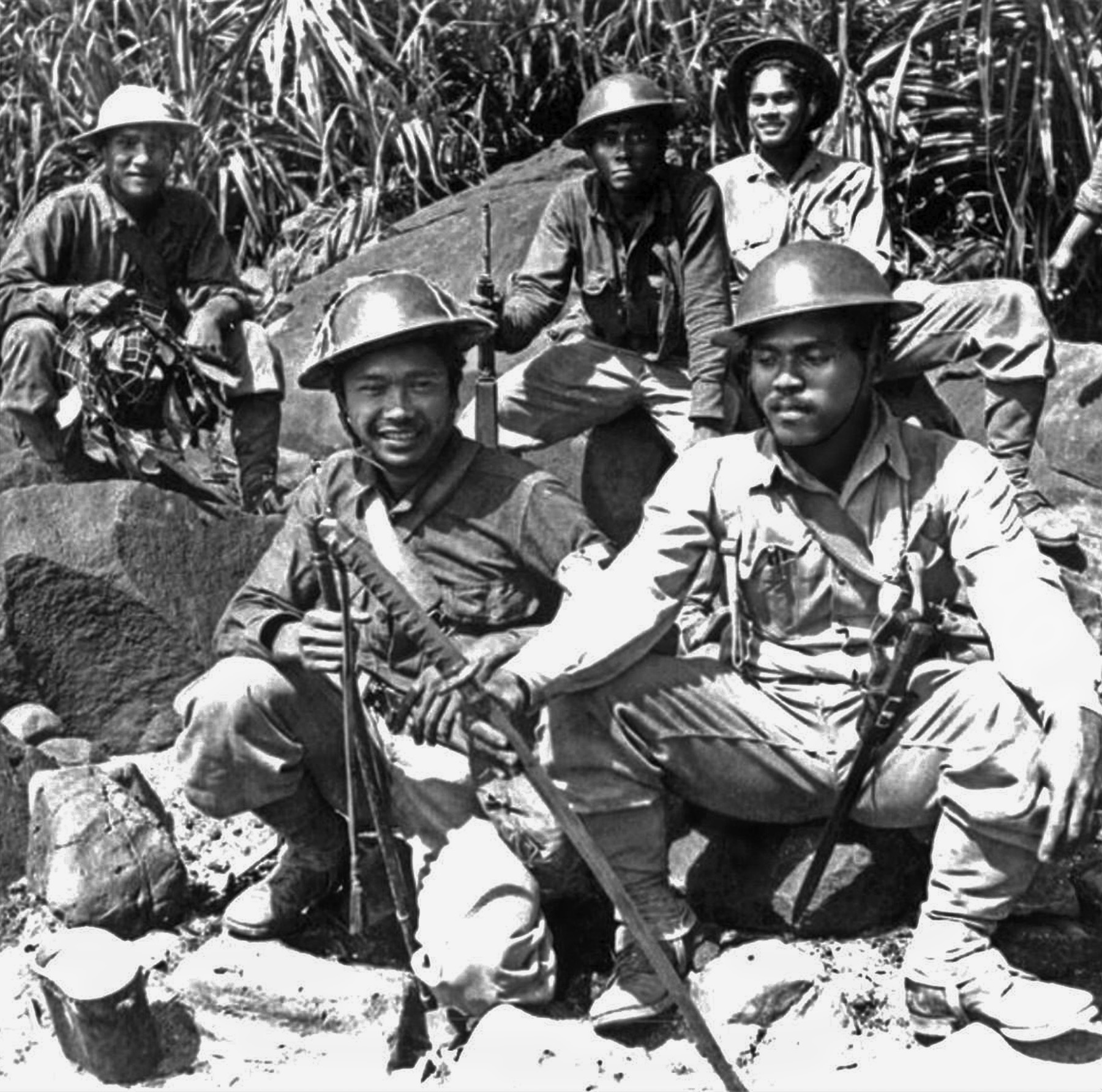

Despite the odds against them, a severe lack of supplies, and near-total isolation from the United States, those troops had managed to put up a bitter, five-month-long battle that began with Japanese air attacks following close on the heels of the Pearl Harbor raid. The defenders had been compelled to fall back on the Bataan Peninsula, fighting their way gradually southward until all that was left was the bastion island of Corregidor and a few scattered units sheltering in the jungles.

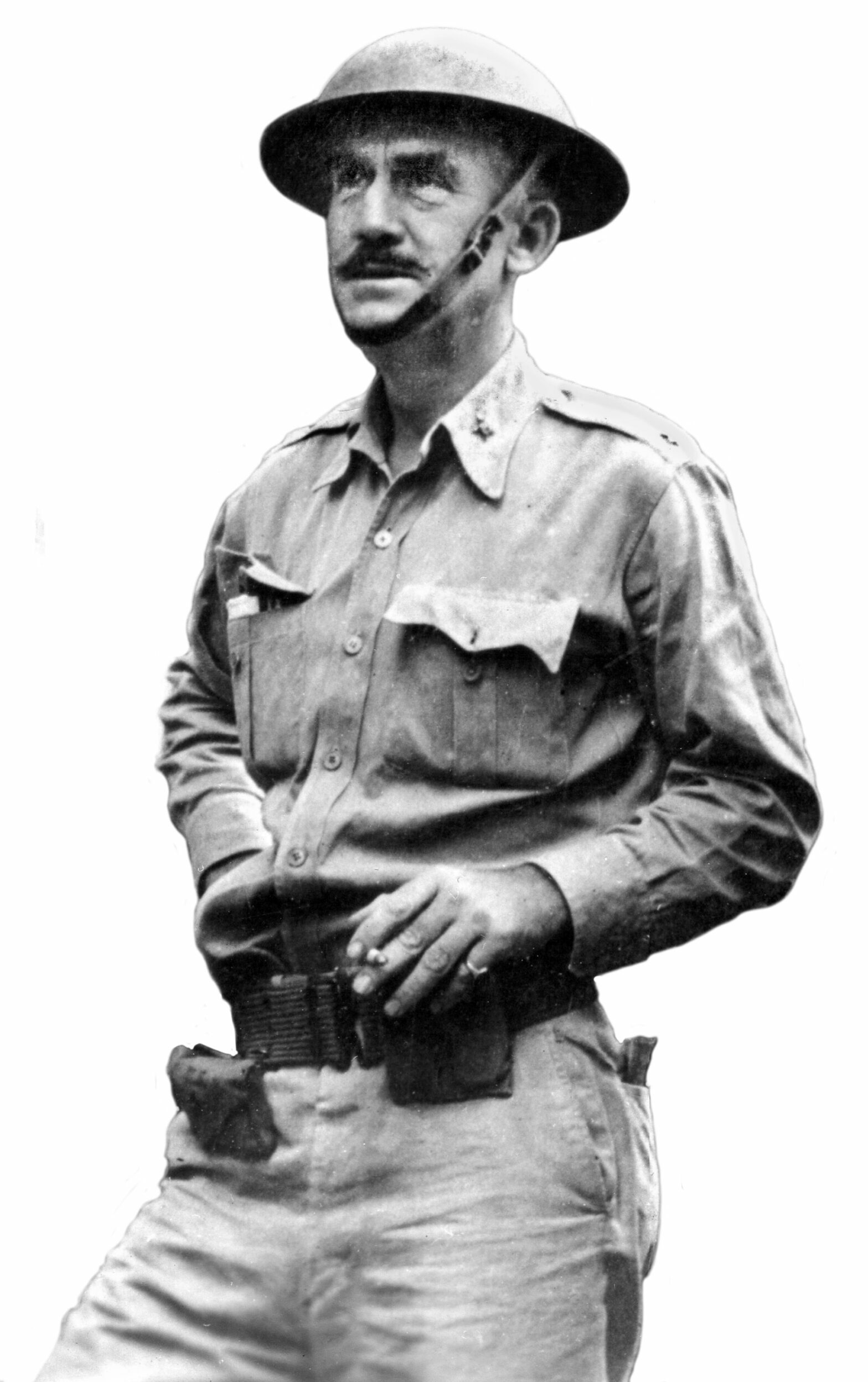

Nick Galbraith was one of the men caught in this maelstrom. Born in 1896, he was the grandson of a Civil War Union cavalry officer. Feeling the calling of that military tradition, Galbraith joined the Army the day the United States entered World War I.

Trained as an artillery officer, in 1940 he was sent to the Philippines, where he commanded a battalion of Philippine Scouts; he was there when the war began. He also served on the staff of General Jonathan M. Wainwright, commander of the U.S. Forces in the Philippines (USFIP) after the withdrawal of General Douglas MacArthur in early March 1942. His role was G-4, military parlance for the logistics officer on the general staff. During the fighting, he was promoted to colonel.

When the end came at Corregidor in May 1942, Japanese flamethrowers were pointed at the entrance to the Malinta tunnel, where thousands of American servicemen sheltered. Wainwright decided there was no further use in fighting and began to discuss surrender with the staff of the Japanese commander, General Masaharu Homma.

These talks stalled when Homma refused to accept the surrender of the troops on the island unless it was accompanied by the capitulation of all the units in the Philippines, including those still resisting elsewhere. The problem was one of communications and even authority.

At this point, the forces on Corregidor were unable to communicate with these other units, and there were questions as to whether Wainwright, who was now at least presumptively a prisoner, had command authority over them. There was no guarantee they would obey a surrender order even if they could be reached.

It was clear that the Americans would have to try, however. General Homma announced he would destroy the remaining garrison on Corregidor, 14,000 men, unless all Allied forces in the Philippines surrendered together; the garrison was to be considered hostage.

Wainwright decided to send representatives to find these units in northern Luzon and Mindinao and convince them to give up. The Japanese thought there was an entire regiment hiding in the mountains of Luzon.

The journey was fraught with peril. Many of the Filipinos still resisting the Japanese were hiding in the same region, regardless of whether they were under American leadership. They often considered any non-American white man to be a German spy, and Galbraith worried he would be a target, particularly since he would be traveling with a Japanese detachment. Anyone with a weapon might attack him, not knowing of his mission or orders.

Galbraith quickly learned of the situation facing him. The American commander of the Luzon forces, Col. John Paul Horan IV, was willing to surrender, but since the forces under his command were scattered and unreachable, there was no way to simply call them in for an orderly surrender. It would be necessary to travel around the mountains make them the soldiers aware of the surrender order.

It was a daunting task, requiring Galbraith to cross battle lines numerous times in search of men who did not want to be found. He would remain at risk from both sides. It was also a physically arduous challenge; months of campaigning on limited rations had left him in relatively poor physical condition; he was malnourished, increasing the risk of disease or injury.

He went into the jungle and began his search, accompanied by his Japanese captors. After six weeks of effort, few Filipino or American troops were located; there was no regiment hiding in the mountains. But the effort was noticed by the Japanese, who actually commended Galbraith before sending him back to General Wainwright, by now being held at a former air training base called Tarlac.

After a few weeks at the Tarlac camp, Galbraith and his fellow officers boarded a ship. They were being sent to Formosa, modern-day Taiwan.

Soon the ship got underway, and the American prisoners were sailing to Formosa, where they would spend the next year and a half. There they would be joined by a number of British and Commonwealth prisoners, including General Arthur Percival, who had recently been forced to surrender Singapore in the largest capitulation in the history of the British military.

While Nick Galbraith was struggling in the Philippines through battle and surrender, a young, newly inducted American soldier named Hal Leith was assigned to give language exams to even newer inductees. Through intensive study he had become fluent in Russian, French, and German. Soon he was assigned to Camp Santa Anita, California, where the Army told him to study Chinese.

One day a man from Washington, D.C., appeared and addressed all the Chinese language students. He told them he was from the Office of Strategic Services, or OSS. The organization was looking for volunteers to work in China. The man cautioned them that if they volunteered they would be expected to become paratroopers, learn armed and unarmed combat, and be willing to operate behind enemy lines. Hal and six others saw it as a challenge and stepped forward.

The young corporal soon found himself at a farmhouse in the Virginia countryside outside Washington, D.C. There he met the famous British Colonel William Fairbairn, who spent many years in Asia and elsewhere as a soldier and policeman, learning all he could about armed and unarmed combat. He taught hand-to-hand combat in the backyard. The students, about 10 of them, had intelligence classes in the living room.

Next they were then sent to Santa Catalina Island off the southern California coast for more intensive training. Most of it involved sending and receiving coded messages, lock picking, and improving memorization.

Hal and his comrades then were sent overseas, eventually arriving ino Kunming, China. In Kunming he finally got his parachute training in June. As a bonus, his contact with the local Chinese reassured him his language studies had paid off; he could communicate with them easily.

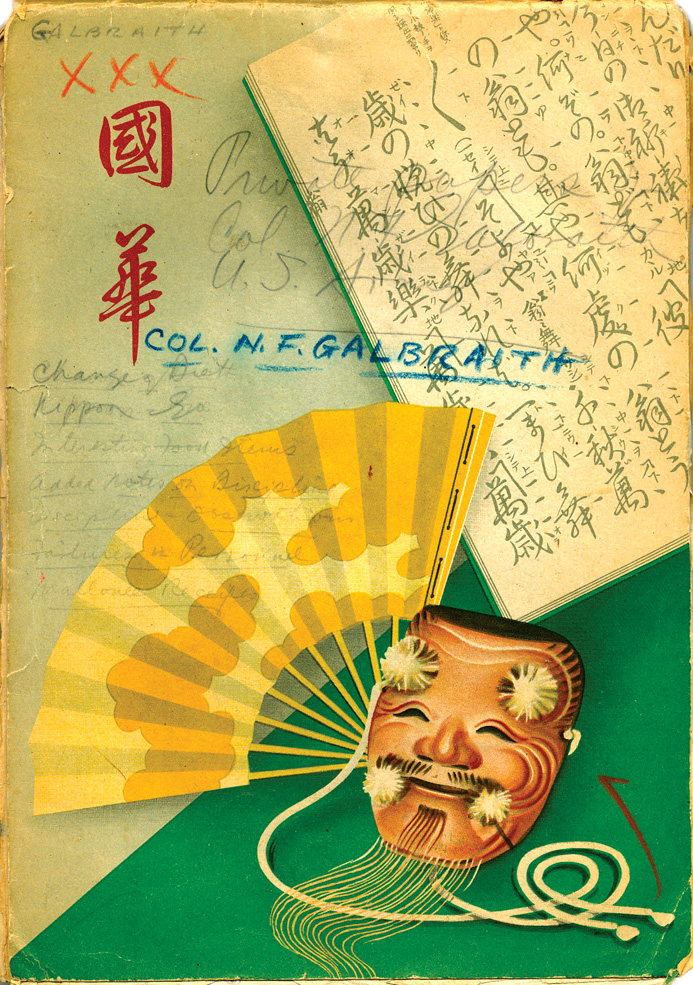

While Hal Leith was preparing for the adventure of a lifetime, the years 1942 to 1945 were hard ones for Nick Galbraith and his fellow prisoners of war. Life in the camps was harsh, tedious, and dull, and he was constantly trying to come up with something to pass the time. Jokes and puzzles circulated the camp, and Galbraith often recorded them in journals he kept to help pass the time. Over the course of his imprisonment he would fill in many notebooks, which he collected from whatever source he could.

He also tried to keep track of the progress of the war, listening to Japanese announcements of victory after victory.

Each Saturday there was a mandatory cleanup of the camp followed by an inspection. The eighth day of each month was nicknamed “Rescript Day.” The prisoners would be formed into ranks to await the camp commandant, who would read the latest Imperial Rescript. The rest of their time was an exercise in deprivation. Soap had to be conserved; they didn’t receive another issue until December 1942, and even that was a single bar. Tobacco was issued only infrequently; it was hard to do without it, and morale improved markedly whenever it was issued. Shaving became a major decision due to the need to conserve razor blades. Replacement clothing was often made from rice sacks and soon became worn, patched, and repatched.

All these problems paled next to the constant shortage of food, however. Rice was the staple of their diet, but there was never enough of it, even when they were eating it three times a day, which they most often did. There were occasional issues of fruits and vegetables such as bananas, grapefruit, and sweet potatoes—the last often reserved for soldiers performing labor. Garden snails became a delicacy. Eventually, the prisoners were allowed to raise goats, chickens, and pigs, though there was seldom enough to keep them well fed.

Nick’s diaries revealed the daily tedium of camp life. The Japanese would often reduce rations if they perceived the prisoners were not working hard enough or were being insolent. There were frequent inspections by the guards. If they did not come to attention quickly enough or did not bow or hold their salute long enough, they were beaten, which Nick called being “bopped.”

Sometimes, a man would be bopped for no discernable reason; General Wainwright was beaten for using the wrong door.

Those who dared to wear shoes in the barracks had their feet beaten with rifle butts. A wounded American named Ives was beaten one day with his own cane. Nick recorded all these events in a simple code he devised so it would be difficult for an English-reading Japanese to understand what he meant. This way he might avoid a bopping of his own.

On June 1, 1943, an event at the camp drew Nick’s particular interest. A Japanese soldier spent two days interviewing various American prisoners, asking them what they thought about the war and how America might treat Japan afterward. In particular, there were questions about whether Japan would be allowed to retain control of Formosa and Korea. The prisoners were also asked what they thought of President Franklin Roosevelt and whether he could stop the war quickly. This led several to wonder if the tide of war was changing.

Through it all, Nick Galbraith kept recording the conditions in his journal, keeping his mind active and creating an in-depth look at the lives of the prisoners of the Japanese Empire.

Finally, on October 10, 1944, new orders arrived to the camp’s senior officers. The prisoners were awakened at 3 a.m. and taken to a port, where they were loaded aboard the Oryoko Maru, a transport ship used alternately throughout the war to move both Japanese troops and prisoners of war. (This ship would be sunk just two months later in Subic Bay, Philippines, while transporting a different group of POWs.) Now, Nick and his comrades were placed into the hold; the heat was terrible and they were without water for a day.

They did not get underway until the night of Monday, October 23, spending most of the time locked below deck. One night there was an air raid, with the prisoners locked in the hold and tracers filling the sky above the harbor. Once at sea, they tried to estimate the ship’s course and speed, but it proved impossible.

Finally, on October 28, they disembarked near Beppu, on the Japanese home island of Kyushu. They still weren’t sure where they were going, but the rumor mill pointed toward Mukden, in the Laioning Province of northern China.

On November 11, they sailed aboard another ship and reached China late that afternoon. Soon afterward, they were in Manchukuo, the Japanese puppet state in Manchuria. It was very cold; Nick recalled giving a British overcoat he had acquired to General Wainwright, who had none.

Occasionally, news of the war trickled in. They heard of a large naval battle at Leyte Gulf, the Russians advancing near Budapest, and of an air battle fought near Taiwan, their former location. Nick noted in his diary a rumor that General MacArthur’s headquarters was back in the Philippines.

A month later, a Japanese colonel arrived to inspect the camp. He met with the camp’s senior officers, stating he had orders from the emperor to care for the prisoners in “body and mind.”

When the colonel left on the 19th, he rode aboard a local taxi made from an old Model T Ford. Its tires had been replaced by wagon wheels; a brown pony and white mule were hitched to the taxi, the driver sitting where the hood used to be. It was an almost comic sight as the driver pulled the single rein and cracked his buggy whip, the horses carrying the colonel away in the decrepit vehicle. Still, it was a sign of the deprivation the Japanese were experiencing this late in the war. Ominously, within a month the first rumors began to spread about the Japanese not allowing any prisoners to remain alive if Japan lost the war.

A final move came on May 20, 1945. Shortly after noon, the POWs were marched to a waiting train, spending three days on it on their way to the Wari Hoten camp. They were combined with another group of POWs who had suffered greatly—out of 1,634 men, only 385 were left. They also heard rumors of 18,000 British prisoners dying while building a railroad in Burma and Thailand.

The last summer of the war brought further deprivation as the Japanese supply system was strained even to meet the needs of its own troops. Cigarette rations, one of the most important things to many POWs, were cut down to a pack a week, if they could be gotten at all.

While they suffered and struggled to survive the harsh conditions, the POWs had no idea that across the Sea of Japan the war was entering its final days as two atomic bombs had laid waste to Hiroshima and Nagasaki, convincing the Japanese leadership to finally end the conflict.

As the war progressed to its end, Allied planners worried over the fate of the prisoners in Manchuria and Korea. Japanese forces on mainland Asia were still intact and in command of the region. It was feared these prisoners might be massacred outright, held hostage, or simply abandoned.

It was known that they were in bad condition after years of captivity. It would take at least a month for Allied teams to make their way inland and find the various camps, so it was decided to parachute teams of men into the camps and take control from the surrendering Japanese.

It was a risky venture; the teams could easily meet the same fates feared for the POWs. The Soviets were expected to invade Manchuria as well, and it was uncertain what they might do now that the war in Europe was over and they did not need the alliance with the West as badly.

On August 12, 1945, the head of the OSS in China, Colonel Richard Heppner, received a warning order. He was to insert six-man teams of OSS personnel near known POW camps north of the Yellow River. They were considered the only personnel with the varied skills needed to handle the delicate and dangerous situation. Corporal Hal Leith was one of those men.

On August 15, his team was flown to Xian in northwest China. The next day, they boarded the B-24 bomber Flight Pay, piloted by Lieutenant Paul Hallberg, and took off for the Mukden area and Camp Hoten.

With Staff Sergeant Leith were two officers. The team leader was Major James T. Hennessy, a 27-year-old West Point graduate. Major Robert F. Lamar, a 31-year-old doctor, was the other. The other Americans were radioman Sergeant Edward A. Starz and Sergeant Fumio Kido, a Hawaii-born “Nisei,” or second-generation American born to Japanese immigrants. The sixth member of the team was a Nationalist Chinese officer, Cheng Shih-Wu.

At 10:45, Lieutenant Hallberg told them to get their parachutes on but warned there were 20-mile winds at the landing site. They decided to go ahead. They had to jump through a hatch in the bottom of the plane.

As he drifted down under his canopy, Hal saw a group of Chinese farmers running toward their landing field. They seemed excited by the sight of the parachutists. Within moments Hal hit the ground, collapsed his parachute, and dumped it. As the team gathered, the B-24 circled back and began dropping supply canisters with their food, radios, and medical supplies.

On the ground, the Chinese farmers helped the team gather their gear. One of the Chinese offered to lead them to the Hoten camp just a few miles to the north. Leaving Starz and Cheng to guard the supplies, the rest started up the road. They barely went half a mile before running into a Japanese patrol that quickly surrounded them, working the bolts on their rifles.

It was a tense moment; Hal managed to speak to one of the Japanese who spoke Chinese, telling him the war was over. The man told Hal they knew nothing about the war being over. Sergeant Fumio Kido spoke to the Japanese sergeant leading the patrol, but it made no difference. Major Lamar was sent back to the landing site with an escort to retrieve the rest of the team and the supplies.

Hal, Major Hennessy, and Sergeant Kido were taken to a nearby building and questioned by a mean looking Japanese officer. A guard with a bayonet admonished them, “No talk!” Eventually, they were blindfolded and placed in a vehicle, which took them through a rainstorm to Mukden, where they were reunited with the rest of the team. All six were taken to the local headquarters of the Kempetai, the dreaded Japanese military police, who wielded almost unchallenged power. They had no idea if they were about to be tortured, interrogated, or simply executed.

Inside, they were taken before a colonel who gave them sake and whiskey. He then told them through Sergeant Kido that they were his guests, not prisoners. He had just heard on the radio the war was over. It was 2 p.m. The colonel told them he had no orders from Japan but would request them.

The Cardinal Team asked to be taken to the camp. The colonel told them they could go to the camp; but the commandant, a Colonel Matsuda, had no orders either, so he probably would not let them meet with the prisoners.

They soon arrived at the camp, but Matsuda refused to let them talk to the POWs. Still, Hal saw some of them watching the meeting, flashed them the OK sign, and waved to them.

The next morning the Kempetai colonel reappeared. He bowed deeply to the Americans and told them he was formally surrendering to them.

They asked the colonel to remain with them and keep order among the Japanese troops in the area. He assigned an escort to take them back to the camp and ordered his soldiers to protect them. The soldier who had told them “No talk!” the day before came up and said, “Hey! I have a brother in L.A.! I wonder if you know him?”

Hal’s team was son back at the Hoten camp. They were taken to Matsuda’s office and given seats. Matsuda was obviously uncomfortable and kept flinching. Finally, they asked to speak with the senior POW; the commandant sent for Maj. Gen. George Parker, the highest ranking man in the camp.

When Parker entered, he immediately bowed to Colonel Matsuda, but then saw the Americans. They told him “no more bowing, the war is over.” They explained about the Japanese surrender and their mission to get the POWs out. Parker was thin, emaciated, but at the happy news he became obviously elated.

Afterward, Hal went out into the courtyard where many prisoners were gathered. Within seconds, he was mobbed by the jubilant crowd, who asked him endless questions. Hal answered as best he could and then walked around the camp. Hal noticed it was crowded, with straw mattresses on boards and fleas and lice everywhere. An American POW in the camp hospital died that day. Behind the camp, 300 more Americans lay buried.

The American POWs now walked as free men, in sharp contrast to the Japanese guards, who were shocked. In the course of a day they were no longer the undisputed masters of not only the camp but of the Chinese in the region.

The Cardinal Team went back to speak with Colonel Matsuda to find the leadership in the camp, in particular General Wainwright. They were surprised to learn that Wainwright and the rest of the high-ranking officers were recently moved to another camp in Hsian, roughly 150 miles northeast of Mukden. It was decided that Hal and Major Lamar would go there in the morning to ensure their freedom.

The next day, some of the Cardinal Team returned to the camp and met with the camp leadership. They distributed K-rations, radios, medical supplies, cigarettes, and rifles. Thousands of pieces of mail had been withheld from the POWs, and now they were passed out. The former guards otherwise stayed out of the camp.

Now Nick could write openly, without fear of a bopping: “I can now write as I choose without that eternal fear of some goddamn savage ramming a bayonet through my guts for some insignificant reason—I need no longer—pick and choose my words, or write in riddles or reverse expressions, but am in a position to speak my mind and thoughts fully and in truth and honesty.

“The only thing they understand, the only power they recognize, the only influence on them is force—might. And it finally gained the position of superiority that forced them to squeal and cry for quarter. How vast a change from the dominating, egotistical attitude while they had the upper hand.”

Over three years of pent-up rage and frustration came out in a single paragraph.

Early on August 18, Hal and Major Lamar boarded a train to Hsian to retrieve General Wainwright.

Arriving at 3 a.m., they met the camp commandant, Lieutenant Marui, a graduate of the University of Oregon.

The next morning they met General Wainwright. Hal was shocked at the man’s appearance, thinking he looked like a scarecrow. He weighed less than 100 pounds and was losing his hearing. Wainwright had endured extensive abuse over the past three years. Often, Japanese privates would beat him just because they could, an easy way to strike out at a superior enemy officer.

With Wainwright were General Percival and American Generals Edward P. King and George F. Moore, both Philippine veterans. They had learned the war was over the day before, but it all seemed incredible after what they had endured for the past three years. The warehouse holding the Red Cross packages was opened, and the food and supplies distributed. A church service, previously banned, was also held.

The next morning, Major Lamar went back to Mukden to coordinate getting the men in Hsian reunited with their comrades. Hal stayed behind to make sure the prisoners were treated properly.

While they waited, Hal spent much time talking to Wainwright, King, and Moore. Wainwright in particular was worried that the American people hated him for surrendering, but Hal told him they actually considered him a hero, something he found hard to believe. General King asked that he not be returned home without his men; he didn’t want to go ahead of them.

Now that Red Cross supplies were available, some of the cooks began making cakes and doughnuts, something the prisoners hadn’t seen in years. At the same time, tension arose when the Soviet Red Army appeared. Hal went with Lieutenant Marui to meet with them.

The general commanding the Soviet forces was unhappy to learn the OSS men had arrived in the area before them and refused permission for them to go to Mukden via train. Instead, they would have to go by trucks and buses with Russian guards. In the late afternoon of August 24, a Soviet lieutenant general appeared with some infantrymen, and they all boarded some requisitioned vehicles and left for Mukden.

While Hal Leith was helping recover General Wainwright, Nick Galbraith helped oversee the liberated POWs in Mukden.

The men were glad to learn they were not considered failures for surrendering, although Nick recorded some bitter feelings about the issue: “They do not seem to realize a large portion of this Bataan ‘hero’ stuff is emotional cover-up for the chagrin and disappointment of defeat—rather than acknowledge the latter, the ‘hero’ tack forces itself forward.

“Of course, there is the other side of the picture as well. The P.I. [Philippine Island] force was well out on a limb—not adequately supplied or prepared by its Govt., which was caught ‘short’—then the delaying action in P.I. forcing Nips to return troops from south for the final assault must have had a great delay on Nips effort at Australia.”

General Wainwright was flown out of China with a few of his staff in time to join the surrender ceremony aboard the battleship USS Missouri on September 2, 1945. MacArthur expressed joy at seeing him again.

Afterward, Wainwright went to the Philippines and accepted the surrender of the local Japanese commander, General Yamashita. He would eventually return to the United States, where he assumed command of the Fourth Army at Fort Sam Houston, Texas. Jonathan Wainwright retired from the Army in August 1947 and passed away in 1953.

Back in Mukden, Nick and his fellow officers spent their time organizing the POWs’ care and then movement to the coast, where they boarded the cruiser USS Louisville and several destroyers on September 13. On the 15th, they arrived at Okinawa, where Buckner Bay was crowded with hundreds of American ships greeting them.

Finally, another ship took the group east to San Francisco, where Nick was met by his wife, Leila, and they made the train ride home to Colorado Springs and their three children.

In 1946 Colonel Galbraith rejoined Wainwright at Fort Sam Houston. While there, he was awarded a Silver Star for his actions in the Philippines; General Wainwright pinned the award on his chest personally. Galbraith retired from the Army in 1950 and passed away in 1986.

Hal Leith stayed in China for several more months, dealing with the aftermath of the war. He encountered more Russian troops, most of whom proved bestial in their behavior, looting and shooting their way through China.

In March 1946, he was discharged and immediately recruited into the OSS as a civilian. He transferred into the CIA upon its creation in 1947 and spent his career there, retiring in 1974. He passed away in December 2013.

These two men’s lives were connected by General Wainwright; one ably served on his staff and endured war and captivity alongside him, while the other began a lifetime of service to his country in his mission to find Wainwright and rescue him. In their writings, neither specifically mentioned meeting the other, but nevertheless their paths came together on the windswept plains of Manchuria.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments