By David A. Norris

Brimming with gale force winds, uncharted reefs, and a force of 21 enemy ships of the line, the bay seemed to be a deathtrap for the flagship Royal George. Sailing master Thomas Conway saw nothing but disaster ahead when British Rear Admiral Sir Edward Hawke ordered, “Lay me alongside the French admiral.” Conway warned that the churning seas ahead of them were littered with shoals and rocks. “You have done your duty in pointing out the danger,” replied the admiral. “You are now to obey my orders, and lay me alongside the Soleil Royal.”

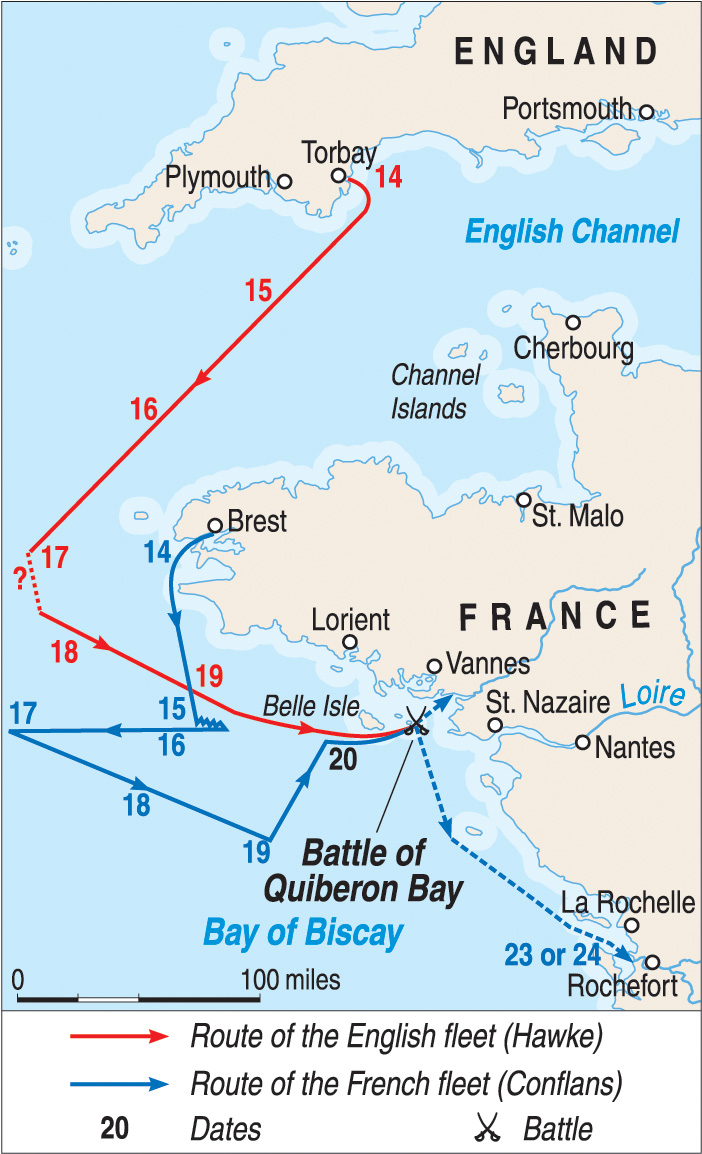

All around Royal George, relentless winds roared in from the Atlantic. Rain spilled from the dark skies into the heaving waves and the salt spray. Without up-to-date charts, the British were sailing through a jungle of unknown shoals. White foam marked the Cardinals, a cluster of deadly rock outcrops that bared their dark teeth like predators waiting for the fragile wooden hulls to come within reach. Naval commanders usually chose the most favorable conditions for giving battle. On this day, however, Admiral Hawke surely chose one of the worst environments ever selected for a major naval battle when he ordered his fleet into Quiberon Bay on November 20, 1759.

Until it was overshadowed by Trafalgar and other famous sea battles of the Napoleonic Wars, the Battle of Quiberon Bay was regarded as perhaps the greatest victory in the history of the Royal Navy. It was a centerpiece of the Annus Mirabilis (miracle year) of 1759. In the Seven Years’ War, the latest in the longstanding, multi-war conflict with France, Great Britain began 1759 in an air of uncertainty. But, as the year unfolded, astounding military successes followed one another. Britain and the allies won the Battle of Minden in Europe, the British captured Quebec, and the Royal Navy won the Battle of Lagos off the Portuguese coast. The year ended with the prospect of a decisive British victory in the war in sight. A crowning achievement in the string of British victories was the Battle of Quiberon Bay.

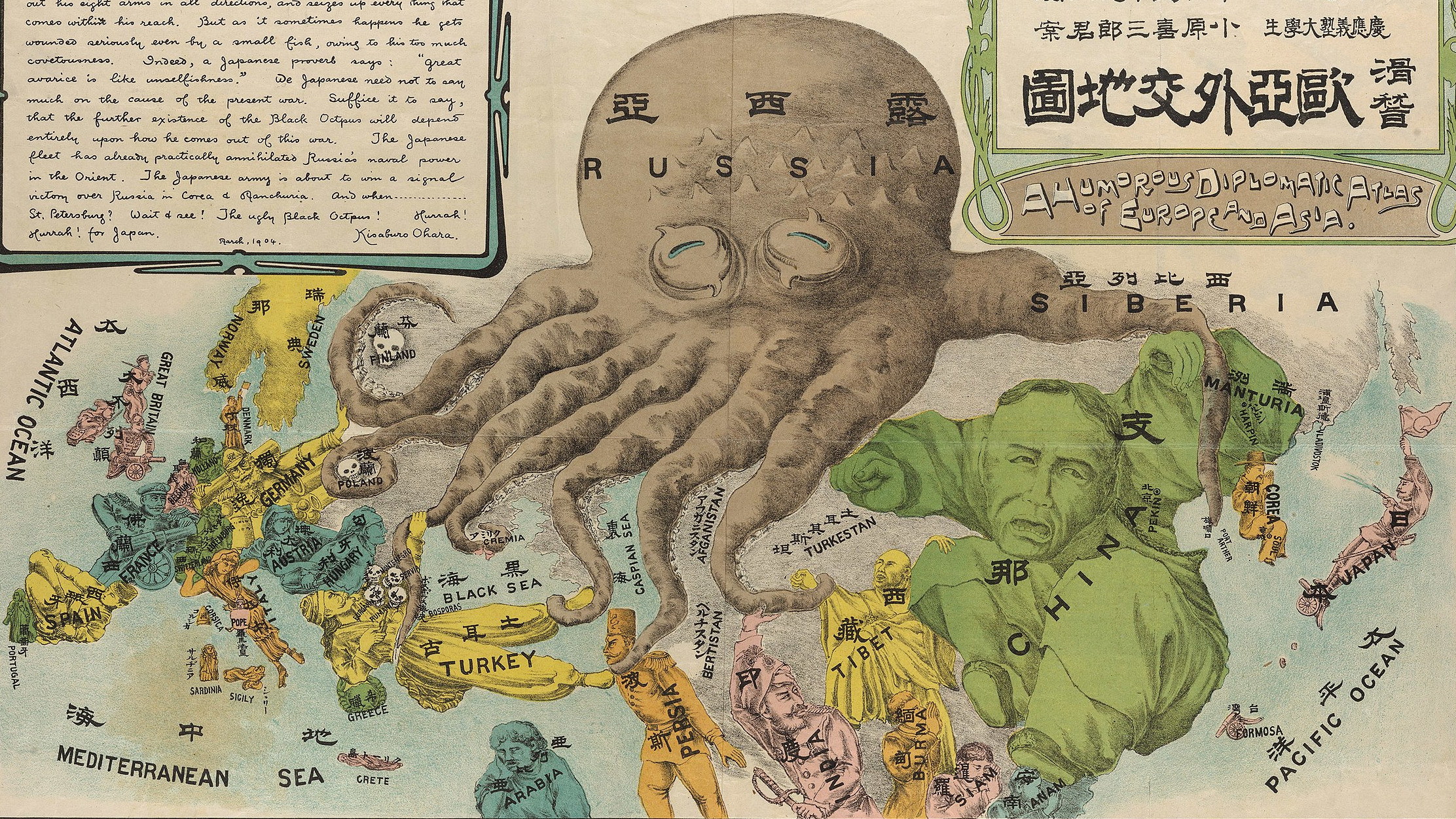

After early military successes, France was wavering under the crushing financial burden of the war. Although it maintained a large and impressive army, France was far behind Great Britain in the number of warships it could put to sea. A long voyage around Spain and Portugal separated the two parts of the French Navy, one based in the Mediterranean Sea at Toulon and another at the Atlantic port of Brest. British naval supremacy kept the French fleets bottled up in their harbors, imposed a tight blockade on the merchant trade, and opened France’s colonies to raids or conquest.

To turn the war around, French Foreign Minister Étienne-François, duc du Choiseul, put into motion a bold and ambitious plan referred to as the “Special Expedition.” Scotland was under occupation since the 1745 defeat at Culloden Moor of the Highland army of Prince Charles Edward Stuart, the Stuart claimant to the British throne. What if a French army was landed in Scotland? Might it spark a rebellion by disaffected pro-Stuart Scots? London, shaken by a rebellion to the north, would throw all of its power against the insurgents and relieve the pressure on France. Perhaps the invasion would induce panic among London’s financiers, and with luck the French and the Stuart-allied Scots could topple the Hanoverian ruler King George II from his throne.

About 20,000 troops—26 battalions of infantry, four squadrons of cavalry, and an artillery detachment—were assembled at Vannes in Brittany for the special expedition. Overall command of the Scottish invasion went to the governor of Brittany, Emmanuel-Armand de Richelieu, duc d’Aiguillon. Plans were made to land other troops in England and Ireland at the same time. Choiseul also began talks to persuade Sweden to contribute another 10,000 or more troops to the plan.

Chosen to lead the ships of the line assigned to protect the troop transports was Vice Admiral Hubert de Brienne, the Comte de Conflans. Born in 1690, Conflans entered the French Navy at the age of 16 and first saw action in 1710, in the War of the Spanish Succession. His years in the navy included service in the Caribbean and actions against the Barbary Pirates. In 1747, he was appointed governor of Saint-Domingue (Haiti) and the French possessions in the Leeward Islands. While en route, however, his ship was captured and he became a prisoner of the English until he was exchanged. During the 1750s, Conflans was appointed an army lieutenant general, a vice admiral, and in 1758, a marshal of France.

Conflans was a competent officer with half a century of experience, but his exalted rank was due to his social position and influence more than skill. Moreover, his navy was settled into a defensive mind-set because of the Royal Navy’s larger fleet and its long roster of previous victories over France. For most of the war, while the British ships were constantly at sea, those of France spent most of their time sheltered in port waiting for an opportunity to slip out. The count had 21 ships of the line under his command at the port of Brest. They were about 100 miles from the transport vessels and troops they were to protect, but with the unbroken blockade in place the transports might as well have been halfway around the world.

Keeping the French hemmed in was Hawke’s Channel Fleet. Hawke was born in London in 1705, and little more than the bare outlines of his early life are known. His father, also named Edward Hawke, was a barrister of Lincoln’s Inn. At the age of 15, Hawke entered the navy as a volunteer on the 20-gun frigate Seahorse. In a navy where influence counted for more than ability, young Hawke benefitted from the help of his mother’s brother, Colonel Martin Bladen. After a time as the comptroller of the mint, Bladen served for many years as the commissioner of trade and plantations. Hawke rose slowly but steadily higher in the officers’ ranks, serving most of the time in the West Indies or off North America. His first command, in 1733, was the sloop of war Wolf.

During the War of the Austrian Succession, Hawke was the youngest rear admiral in the service. Off Cape Finisterre in 1747, he tried an unorthodox battle plan when he attacked an enemy convoy. Instead of the standard naval practice of keeping his ships in a single line of battle, he broke up his formation and ordered each of his ships to chase individual foes. Hawke’s plan was successful, and he took half a dozen warships. In the West Indies, the poorly protected convoy was intercepted, and 40 ships were taken.

The War of the Austrian Succession ended in 1748, bringing only a few years of peace. On the frontiers of the French and British colonies in North America, the French and Indian War began in 1754, merging with Europe’s larger Seven Years’ War in 1756. Hawke began the war with a command in the Mediterranean, succeeding Admiral Sir John Byng, who was court martialed and shot for his failed attempt to relieve a French attack on Minorca in the Balearic Islands.

Hawke was later assigned to command the Channel Fleet. He kept a relentless watch on enemy shipping. Unlike the practice in previous blockades, ships remained on station even in harsh weather. A well-organized system of regular supply ships kept the sailors provided with fresh food. Despite long spells at sea, scurvy did not appear on board the ships, and Hawke’s insistence on keeping the ships clean helped ward off other diseases.

The core of the Channel Fleet was its collection of ships of the line. Greatest in size of the world’s war vessels, ships of the line, which carried from 64 to 100 guns, were the 18th-century equivalents of the battleships or aircraft carriers of later eras. By 1759, the Royal Navy was partial to a new design with 74 guns arranged on two decks rather than three to improve their sailing qualities. So overwhelming was their armament that when in line of battle, they traditionally didn’t even bother to fire on enemy frigates or corvettes unless impudent captains of such small vessels dared to fire first.

British shipbuilding was competent but not innovative. England’s best designed vessels in this era were those captured from the French or duplicates such as the new 74s of the 1750s that were carefully copied from prizes. Several of Hawke’s vessels had been launched in the 17th century. For example, the 90-gun Duke was completed in 1678. Duke and these other older vessels, though, had been rebuilt at least twice. This rebuilding could be so thorough that practically every piece of wood was replaced. Although the resulting ships were built of new timber, their new incarnations were kept close to the outmoded designs of their originals.

However, a navy needed much more than the powerful but ponderous ships of the line. Frigates, which were faster than their heavier brethren but more lightly armed, patrolled closer to the shore than their larger counterparts. They kept a ceaseless lookout on enemy ports and prowled the oceans to detect enemy convoys and fleet movements.

Flying his flag from the elderly 90-gun Ramillies, Hawke divided his fleet into three parts. Most of his vessels were based off Ushant, poised at the tip of Brittany and ready to sail into the English Channel or the Bay of Biscay as needed. Captain Augustus Hervey kept a detachment on a special watch on the port of Brest. Captain Robert Duff, with four 50-gun ships and four smaller frigates, was stationed inside Quiberon Bay. By this time, 50-gun ships were regarded as too small to fight in line of battle with the larger vessels, but Duff put them to good use in snapping up small prizes in the bay.

Quiberon Bay is southeast of Lorient and northwest of St. Nazaire and the mouth of the Loire River. Roughly 30 miles across and 10 miles wide, the bay is bracketed by the Presqu’ile de Quiberon (or Quiberon Peninsula) on the northwest. To the south of the peninsula is Belle Isle. Closer in and a bit to the east are the smaller islands of Houat and Hoedic. The Cardinals lurk southeast of Hoedic Island. Elsewhere, other rocks and shoals (called plateaus on French charts) made navigating the bay tricky to mariners without current charts or local knowledge. Deep inside the bay are two protected anchorages: a natural harbor, known as the Gulf of Morbihan, and the mouth of the Vilaine River.

Tucked safely inside the Gulf of Morbihan at the town of Vannes was the growing fleet of French transports that Versailles hoped would accomplish what the Spanish Armada could not. The ships of the line at Toulon were to elude the British, pass Gibraltar, and rendezvous with the fleet from Brest inside Quiberon Bay. From Quiberon, the ships would sail around the west coast of Ireland and land the soldiers somewhere along the River Clyde, on the west coast of Scotland. From the Clyde, the invaders would capture Edinburgh, enlisting Scottish recruits to swell their army. Meanwhile, Conflans’s ships of the line would sail around the north of Scotland and return to Europe to pick up more troops for an invasion of southern England.

The French invasion plan was neither practical nor possible to keep secret. With the ceaseless blockade, the French Atlantic ports were largely useless. Troop and supply shipments for the expedition had to be sent overland or by small coastal vessels. A raid led by Rear Admiral George Rodney destroyed scores of boats specially constructed for the soldiers, and also the shipyards and arsenal at Havre-de-Grace on July 4, 1759. Rodney’s raid essentially ended any hope of adding the landing in southern England to the Scottish invasion plan.

Another blow fell on the expedition a few weeks later. The Toulon fleet escaped on August 5, 1759, when Admiral Edward Boscawen had to take his fleet from its station to refit at Gibraltar. Learning of the French move, Boscawen went in pursuit and caught the French off the coast of Portugal on August 18 and 19. In the clash, the Battle of Lagos, the French fleet was dispersed with the loss of five ships of the line taken or burned.

Choiseul and other French officials still intended to invade Scotland, even after the loss of the Toulon ships. Originally, five ships of the line were considered enough to escort the troop ships. At Conflans’s insistence, he would take every one of the available ships of the line. About 60 more transports built in Bordeaux or Nantes slipped past the British into the Morbihan.

During the summer and fall of 1759, Hawke found the sea a more persistent adversary than the French, sometimes driving his blockade ships off station to find shelter along the English coast. In mid-October, heavy westerly gales again forced the British blockaders to take refuge at Torbay. When they returned to their station, news reached Hawke that Conflans had orders to sail. At this potentially critical moment another gale arose. Three days of heavy winds and rain lashed the ships so that the British were again driven to Torbay on November 9.

By this time, the old Ramillies was deemed unseaworthy, and while in port Hawke transferred his flag to Royal George. Launched at Woolwich in 1756, this three-decker was rated at 100 guns and was the largest ship in the Royal Navy. She was 178 feet long with a beam of 51.5 feet. Her burden of 2,116 tons was 600 tons or more than most of the other ships with Hawke or Conflans. “Being a flag-ship, her lanterns were so big, that the men used to go into them to clean them,” said an old hand who sailed on the vessel.

In November, Conflans took advantage of the storm to slip away while the blockade was temporarily lifted. He also received another lucky break. Driven to refuge by the same gales that drove Hawke to Torbay, several French warships returning from the West Indies or the Pacific sailed into Brest. All of the new arrivals needed repairs before setting out to sea again, but 500 veteran sailors were transferred to Conflans’s force. Each of the new arrivals received a gold pistole (a coin worth about 18 English shillings) as an enlistment bonus.

The reinforcements were very welcome. Other than crewmen on fishing boats and small coasters, it seemed that every available mariner in the kingdom was already pressed into naval service, but the waiting warships were still undermanned. A large proportion of their crews were also landsmen. Among their ranks were hundreds of farmers from Brittany. Another source for manpower were the companies of the gardes-côtes, army militia units that had been intended to repel coastal attacks.

On November 14, the French sailed from Brest with 21 ships of the line and five frigates and corvettes. Atlantic winds still lashed the coasts and waters. Conflans expected to make the 100 miles to Quiberon Bay without interference from the British, whom he thought were still at Torbay. By November 15, the French were only 30 miles from the entrance to the bay near Belle Isle.

Hawke tried to leave Torbay on November 12 to get back on station, but winds pushed his ships back and kept them there until they got away on November 14. Although Conflans had a shorter distance to cover, luck was with Hawke. Contrary winds held the French, who were so close to their destination on November 15, to making only a few miles of progress. Well trained from the grueling months of blockade duty, the crews of the Channel Fleet were able to deal with the gales and push their way toward France.

The escape of the French was not secret for long, and their fleet was spotted by several British vessels. Even the supply ships that shuttled between England and the blockaders were on the lookout. On November 16, Hawke was 45 miles off Ushant when four British victualler vessels came into view not long before dark. They were returning from delivering supplies for Duff’s ships in Quiberon Bay. On the previous afternoon, the victuallers were 70 miles west of Belle Isle when they spotted 18 ships of the line.

At dawn on November 20, Conflans neared the bay. So far as he knew, Hawke was still sheltered far away at Torbay instead of bearing down on him with 23 ships of the line. Included in the French admiral’s orders were instructions to take or destroy Captain Duff’s frigate squadron. Expecting to catch the frigates by surprise, Conflans no doubt thought he would quickly take the isolated and outnumbered ships on the way to pick up the invasion force.

Duff, however, was not caught unaware. Earlier that morning, the Royal Navy frigate Vengeance entered the bay. Firing its guns as rapidly as possible, Venegance warned the other frigates that Conflans was on the loose and heading for Quiberon Bay. Captain Duff immediately signaled his ships to cut their cables. First, they tried to slip out past the north end of Belle Isle, but the wind shifted and only one of the frigates was able to get through.

Steering to round Belle Isle by the south, they then saw the enemy fleet. Duff’s ships turned away from the French, and Conflans ordered a chase. The vanguard of the French was nearly within cannon shot of the slowest of the British frigates, Chatham, when a cry went out from a lookout on the English frigate Rochester. Posted on the main topgallant yard, the lookout had seen another flock of sails in the distance.

Meanwhile, at 8:30 am, the frigate Maidstone of Hawke’s fleet signaled that she had spotted the enemy. Hawke commanded his ships to form “line abreast, in order to draw all the ships of the squadron up with me.” By 9:45 am, it was confirmed that the mysterious vessels definitely were Conflans’s ships.

After some anxious minutes, the hands on Rochester cheered, and many threw their caps into the sea. They knew now that the new sails coming over the horizon belonged to Hawke. Duff ordered his ships to turn again and make for the enemy. Surprised at first at this seemingly suicidal move, the French soon knew that the Channel Fleet was near.

Conflans called back the ships pursuing the frigate squadron and began forming a line of battle outside the bay; however, the winds continued blowing heavily from the west-northwest. Conflans was near a lee shore with a potentially larger enemy force bearing down on him. Deciding against risking a general engagement on the open sea, he ordered his ships continue on to take refuge in Quiberon Bay. With the bay’s numerous rocks and shoals, largely unknown and uncharted to the British, Conflans assumed Hawke would never risk disaster and shipwreck by following him in.

November 20, 1759, went down forever in naval history because Hawke did exactly what his enemies assumed he would never do. Ignoring the danger posed by the rocks and shoals, Hawke signaled for a general chase. The winds increased to an estimated 40 knots, even as the ships neared the Cardinals, the deadly rocks that lurked near the entrance to the bay. It was these rocks that gave the French one of their names for the impending clash, la Battaile des Cardineaux.

Conflans, aboard his 80-gun flagship Soleil Royal, led his vessels into the bay. This was a practical way to show the ships where they should go, but in the aftermath of the battle this made it appear that Conflans was leading a retreat. If the French had sailed deep into the bay and drawn up in line of battle, they might have placed Hawke between themselves and the dangerous lee shore. But, Hawke pressed on aggressively, following as closely as possible with the intention of bringing battle. In effect, Hawke’s captains trusted the skills of the French pilots, believing that by following in their wake they could avoid the perils lurking beneath the surface.

By 2:30 pm, Hawke was south of Belle Isle. Ahead of him, Soleil Royal was rounding the Cardinals and heading for the inner part of the bay. Guns of the lead British ships and the French rear squadron opened fire. From Royal George came the signal for engaging the enemy.

As the gap between the fleets closed, the storm intensified as well. Wild squalls pounded the ships, scattering some and pushing others together. Some of the vessels battled only the storm without being able to clash with the enemy. One ship that took a heavy share of enemy fire was the 80-gun Formidable, part of the rear guard of the French fleet and the flagship of Rear Admiral Count St. André du Verger, who was third in command of the force.

Captain Robert Howe’s Magnanime was in the lead of the British ships. Howe’s guns fired some of the first effective shots of the battle at Formidable. Several of Formidable’s officers were already incapacitated by seasickness when the firing started. Du Verger’s ship took broadsides from several other passing British vessels. The French admiral was hit early in the action. Taken below, the wounded commander was patched up by a surgeon and brought back on deck.

The tactic of forsaking the traditional line of battle had worked well for Hawke at Cape Finisterre, and he intended to repeat his strategy of letting his captains choose their foes and go after them. Certainly, in any case, the rising storm would have made maintaining lines of battle impractical or impossible. Action was steady for some ships and sporadic for others. Winds shoved combatants together, pulled them apart, and reshuffled the ships to find new opponents.

In its position near the rear of Conflans’s fleet, Formidable fought several of the British vessels as they pushed ahead to pursue the rest of the enemy. Too badly wounded to stand, du Verger commanded his men from a chair. The French admiral directed the battle until he was decapitated by a cannon ball. Stepping in to command the ship, de Verger’s brother was cut in half by another shot soon thereafter.

Howe turned Magnanime to pursue the 74-gun Thésée. An attempt to board the Frenchman failed, stated Howe, because of “the slow wearing of the ship for want of head sails.” While maneuvering for another attack, Magnanime was rammed by another British ship, Warspite. As the crews worked to separate their ships and return to the battle, another friendly vessel was out of control in the gale and crashed into them. This collision with Montagu carried away Howe’s topsail yard. After separating from Warspite and Montagu, Magnanime turned to attack the closest French ship, the Héros.

By this time, Royal George had rounded the Cardinals. It would have been about then that Hawke made his legendary remark to the pilot. Sailing into the bay, the Royal George opened fire on the 70-gun Superbe. After taking two broadsides, Superbe suddenly sank with all hands. Possibly the ship’s quick loss was hastened by water rushing through the lower gun ports.

Thésée was hotly engaged with Captain Augustus Keppel’s 74-gun Torbay when a squall swept over them. Water surged through the open lower gun ports of both vessels. Keppel’s crew fended off disaster, closing the gun ports and turning into the wind, saving the ship.

Thésée’s complement of 800 was mostly landsmen drafted from farms and villages. There were too few hands or officers with experience in storms, and keeping the lower gun ports open doomed the ship. Fatally flooded, Thésée plunged beneath the surface with shocking speed. Despite the winds and the heaving seas, Keppel ordered boats launched to pick up survivors. Torbay’s boats returned with nine French prisoners. Only 20 more men survived the sinking. They clung all night to the topmasts and were taken prisoner by the British the next day.

Commentator Horace Walpole later reported a tale that went around London after the battle. For a few moments, Keppel had believed that Torbay would join Thésée on the bottom of Quiberon Bay as thousands of gallons of seawater poured through the lower ports. The crew saved the ship, but Keppel was told that the water had ruined all of his remaining gunpowder. “Then, I am sorry I am safe,” said the captain. When Keppel got word that some dry powder had been found, he ordered, “Very well, then attack again.”

Flying their admirals’ pennants, Royal George and Soleil Royal traded broadsides with each other. The clash between the flagships was interrupted when 74-gun Intrépide pushed between the combatants and the outgunned Soleil Royal broke off the battle and pulled away to the north.

When Howe’s Magnanime caught up with Héros, the French warship had already taken considerable damage from other vessels. Magnanime was steered alongside Héros so closely that a fluke was knocked off one of Magnanime’s anchors. Héros struck her colors to Magnanime, but the storm was at such a pitch that it was impossible to send boats to accept a formal surrender. Hours after dark, no one had arrived to take possession of Héros, so the captain ran her ashore and the crew escaped.

Aboard the shattered Formidable, the planks, sides, gun carriages, and all the other woodwork on the gun deck had been painted red according to standard naval practice. The surgeon and his assistants treated the flood of wounded as best they could. In the dim light of the fading afternoon, the blood of the scores of dead and wounded sailors blended with the paint. Five hundred of the crew were dead or wounded, and a dozen officers were dead from cannon shot or musketry. At 4 pm, the ship struck her colors. Surgeon Patrick Renny of the frigate Coventry later visited the ship and wrote, “The destruction of her upper works was dreadful, and her starboard side was pierced like a cullender.” A French army lieutenant colonel told Renny that he was the only man of his detachment who was not hit. A veteran of 30 years’ service, the French officer had been at the Battle of Fontenoy in 1745 but “had never before witnessed such a scene of carnage.”

As darkness ended the short but deadly November day, all the remaining French ships were fleeing. Amid the unfamiliar waters, Hawke ordered the fleet to anchor. At the time, the Royal Navy’s signal for “anchor by night” was for the flagship to fire two guns without using a light or other signal. Most of the ships never heard the signal or could not distinguish between such a signal and the final shots of a battle. This left Hawke’s ships scattered, each one finding its own anchorage. Roaring throughout the night, the winds carried the sounds of guns firing distress signals. No one knew whether the ships in danger were friends or foes, and no boats could be risked to find out.

The next dawn brought a great surprise to the British. Anchored among them was the greatest of potential prizes: the enemy admiral and his flagship Soleil Royal. Quickly cutting her cable, Conflans’s flagship made a run for the protection of the shore batteries at Croisic. Straightaway, Essex steered in pursuit. A short time later, Soleil Royal ran aground, but the same fate also befell Essex.

Also seen in the light of the new day was the unfortunate Resolution, which was visible wrecked on the Four Shoal. And, so it was that Hawke lost two ships of the line, not to the enemy but to the shallows of Quiberon Bay. Despite the warnings of the captain, about 80 of Resolution’s crew tried to escape on rafts. In a terrible twist of fate, the men who boarded rafts in their desperation to avoid capture were lost in the still raging waters of the bay. Both Essex and Resolution were later set afire after their crews were picked up by their comrades.

Some distance to the north of Hawke’s ships, seven French ships of the line huddled together. Their crews shoved heavy guns, anchors, and crates and barrels of supplies overboard. Thus lightened by many tons, the seven ships were able to escape from the bay by slipping over the bar at the entrance of the Vilaine River.

The rest of Conflans’s ships of the line, nine in number, escaped past Hawke into the open sea. Only eight of them found safety in Rochefort. The ninth, the 70-gun Juste, had already lost its captain and second in command during the battle. Attempting to enter the Loire River, Juste ran aground with the loss of much of its crew.

Hawke wrote in his report that if he’d had two more hours of daylight, the entire enemy fleet would have been taken or destroyed. “When I consider the season of the year, the hard gales on the day of action, a flying enemy, the shortness of the day, and the coast they were on, I can boldly affirm that all that could possibly be done has been done,” Hawke wrote in a dispatch to London. Hawke added to one letter he wrote after the battle, “I am so cold I can scarce write.”

On November 22, the winds moderated and Hawke sent detachments to set Héros and Soleil Royal afire. The French beat them to burning Soleil Royal, while a British party set Héros on fire.

Eyeing the ships huddled in the Vilaine, Hawke planned an attack with fire ships. Soundings were made of the approach to the anchored French vessels. Plans called for Coventry and one of the other frigates to be run ashore in front of the two batteries guarding the river entrance. With the frigates blocking the French guns, the fire ships and assault parties in ships’ boats would be protected from the batteries. The fire ship attack was planned for midnight on November 22, to coincide with high tide.

“We every moment expected the signal to slip the cables and run in,” wrote surgeon Renny. But as the operation was ready to begin, the wind shifted and started blowing from the shore, and the attack was called off for the night.

Plans were abandoned the next day as further investigations showed that the seven ships were well protected in their new haven. Tucked away in the Vilaine, the ships were lost to the French by being bottled up by the Royal Navy. Four of them broke their keels and never sailed again. The remaining ships were trapped until they managed to slip away in 1761.

After the battle, a lieutenant and 80 men from Coventry were sent to repair Formidable. With them went Surgeon Renny, who was stunned at the scenes of misery that he found. “The grand chamber was filled with wounded officers, many of whom had the tourniquets still screwed on the stumps, the vessels not being taken up, although it was the third day after the battle,” wrote Renny.

When questioned, Formidable’s surgeon explained that even with six surgeons’ mates, he still had not been able to see all the casualties. Below, “the large gun-room, and every space between the guns on the lower deck, was crammed with wounded soldiers and sailors, besides three rows of cradles in the hold, containing 60 seamen.” After two more days of misery, a cartel was arranged so that the French wounded could be paroled. Renny had little hope for the survival of many of the patients “considering their very miserable situation and circumstances.”

Her prize crew struggled to keep the battered hull from sinking all during the trip to England. The captured ship “was dismasted in a storm, her coppers were washed away, and the prize crew and prisoners lived for four days on the boatswain’s tallow,” according to Renny. On December 22, with jury main and mizzen-masts, Formidable arrived in Plymouth. Purchased by the Royal Navy, the prize would lay at anchor for years. Repairs were begun, but she was never taken into service, and the ill-fated ship was broken up in 1768.

Altogether, the French lost six ships of the line: one captured, two sunk, and three wrecked. Estimates of French casualties included 2,500 dead and unknown numbers of wounded.

Hawke lost only Essex and Resolution, which fell to shipwreck rather than enemy action. The British butcher’s bill was usually given as 39 seamen and marines dead and perhaps as many as 250 wounded. Only one officer was killed, a Lieutenant Price from one of the most heavily involved ships, Magnanime. Apparently the only serious wound among the officers was to Captain Baird of the Defiance, who lost a finger. Contemporary British accounts of the victory omitted about 80 men who died trying to get away from the wreck of the stranded Resolution.

Glad tidings of the victory at Quiberon Bay reached London at the most ironic moment possible. Not long before the battle, news of the escape of Conflans’s fleet from Brest had reached England and aroused considerable anxiety. In London, an angry mob was burning Hawke in effigy. Instantly, Hawke was lauded as a national hero. Quiberon Bay, which ended the threat of a seaborne invasion of England, seemed comparable to the repulse of the Spanish Armada. Parliament

granted the victorious admiral a lifetime pension of 2,000 pounds a year. Far away in Boston, Massachusetts, where the news didn’t arrive until February 1760, all the cannons in the city’s defenses fired a salute in honor of the victory.

In the afterglow of success, Hawke served as First Lord of the Admiralty from 1766 to 1771. In his years at the helm of the admiralty, he battled to force reforms in the supply service and the dockyards. Hawke’s new foes were the entrenched alliance of inertia, incompetence, corruption, a parsimonious peacetime Parliament, and outside influence that had long plagued the Royal Navy. They were impossible for any one administrator to overcome. His efforts were only partly successful by the time he retired. In 1776, he was raised to the peerage and became the 1st Baron Hawke.

After their disaster at Quiberon Bay, the French abandoned the idea of an invasion of Scotland. The soldiers who were to have taken Edinburgh Castle were dispersed to routine garrison duty. Many of the sailors of the warships uselessly trapped in the Vilaine were discharged, and some ended up begging for alms. A pall of grief hung over the farms and villages of Brittany, home of hundreds of the doomed farmers and militiamen who on their first trips to sea perished in the wrecks of Superbe, Thésée, and Juste.

With the other victories of 1759, Great Britain was on its way to becoming the mistress of the seas and the world’s greatest superpower until the 20th century. The famed naval anthem “Heart of Oak” was inspired by this battle. With words written by the popular actor David Garrick, it premiered at Garrick’s patriotic production Harlequin’s Invasion at the end of 1759. Its lines are quoted in countless works of naval history and fiction: “Come, cheer up, my lads, ‘tis to glory we steer,/ To add something more to this wonderful year.”

Far from the cozy townhouses of London theater goers, stormy weather assailed the ships on blockade duty off the French coast. During the summer and fall Hawke’s men had grown accustomed to his unusual attention to bringing them fresh provisions and beer. Now, the unending gales cut off supplies from England, and rations grew short. A new poem, rather less stirring than “Heart of Oak,” went around the fleet:

Ere Hawke did bang

Monsieur Conflans,

You sent us beef and beer;

Now Monsieur’s beat,

We’re naught to eat,

Since you have naught to fear.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments