By Glenn Barnett

For centuries wounded soldiers of every nation were responsible for much of their own care. Medical attention was primitive and often not a high priority for military planners beyond the officer corps. Sick and injured men had to find their own way home from distant battlefields. Armies of peasant conscripts commanded by an insensitive royalty were unprepared to adequately care for and transport men who were mutilated in war. Wealthy nobles who could afford it often brought their own doctors to the battlefield to treat their maladies. The common soldier died where he fell.

Amputations, if performed at all, were unspeakably primitive. Gangrene and disease were passively accepted as inevitable. Surviving veterans who were blinded or deafened or traumatic amputees spent the rest of their lives as charity cases begging alms from passersby.

All that began to change in the 18th century when better medications combined with swifter transportation became available. Great strides in care for the wounded evolved out of the Crimean War and American Civil War. The effort was led by caregivers such as Florence Nightingale, Clara Barton, and Walt Whitman. Horse-drawn ambulances and regular military hospitals with modern equipment were among the innovations.

By World War I, motorized ambulance service whisked casualties from the front to treatment centers with trained staff. Railroad lines carried them in relative comfort to rear-area hospitals, and steamships brought wounded Canadians and Americans safely home across the waters in a relatively short time. But the advances in medical science in World War II were an exponential leap in the saving of lives and the comfort and recovery of wounded soldiers.

50,000 Physicians

World War II began abruptly for the United States on a quiet Sunday morning in Hawaii. Like all other branches of the military, the U.S. Army Medical Department had to swell its ranks quickly to meet the challenge of total, and global, war.

Unlike the fighting branches of the military, not just any recruit or draftee qualified for this highly technical service. Trained medical personnel were needed, and lots of them. Under the taciturn direction of Surgeon General Norman T. Kirk, the department grew rapidly. From a peacetime Army that boasted only 1,200 doctors, the department eventually enlisted as many as 50,000 physicians by the end of the war in Europe. For the first time in history, 83 of the Army’s doctors were women.

In addition, 15,000 dentists wore the Army uniform. Two thousand veterinarians treated the injuries of pack animals and oversaw their slaughter for food. The number of nurses in the Army Nurse Corps (ANC) rose from 1,000 to 52,000. By June 1944, all nurses were commissioned as officers. The department also enlisted 1,500 dietitians, 1,000 physical therapists, and 18,000 administrators.

In addition to the enlisted professionals, thousands of regular GIs served as medics, litter bearers, and ambulance drivers. Men often volunteered for these duties on the basis of religious beliefs or pacifist sentiment. The number of men needed for the Army reflect but do not include the parallel growth of medical personnel needed by the Navy.

Added to the department’s herculean task was the fact that at the outbreak of war it owned few medical instruments. Most of that equipment had been made in prewar Germany. No new shipments could be expected. A whole new manufacturing base had to be created in the United States to make the thousands of instruments and medications that would be needed.

Some creative Army dentists found that by baking little balls of acrylic resin and painting them to specification they could make artificial eyes that were lighter, stronger, and safer than the German-produced glass eyes.

Portable Surgical Hospitals: Precursors to MASH

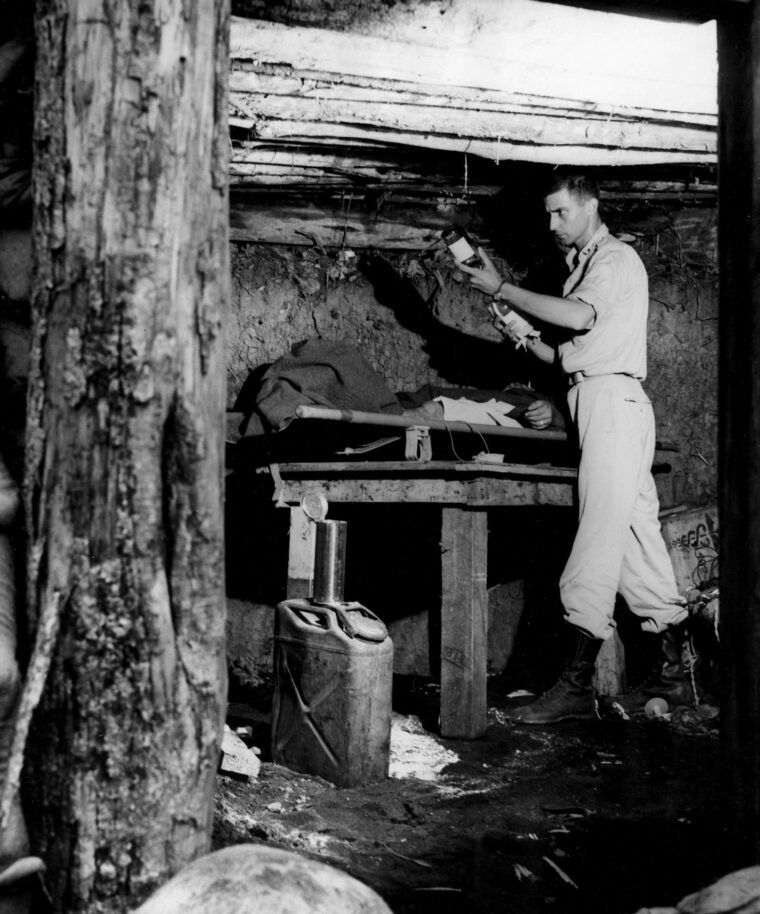

The Mobile Army Surgical Hospital (MASH) of the Korean War depicted in the movie and television series is the Army medical unit of the popular imagination. But the genesis of MASH was born of necessity in the hostile jungles of New Guinea in World War II. They were originally called Portable Surgical Hospitals (PSHs).

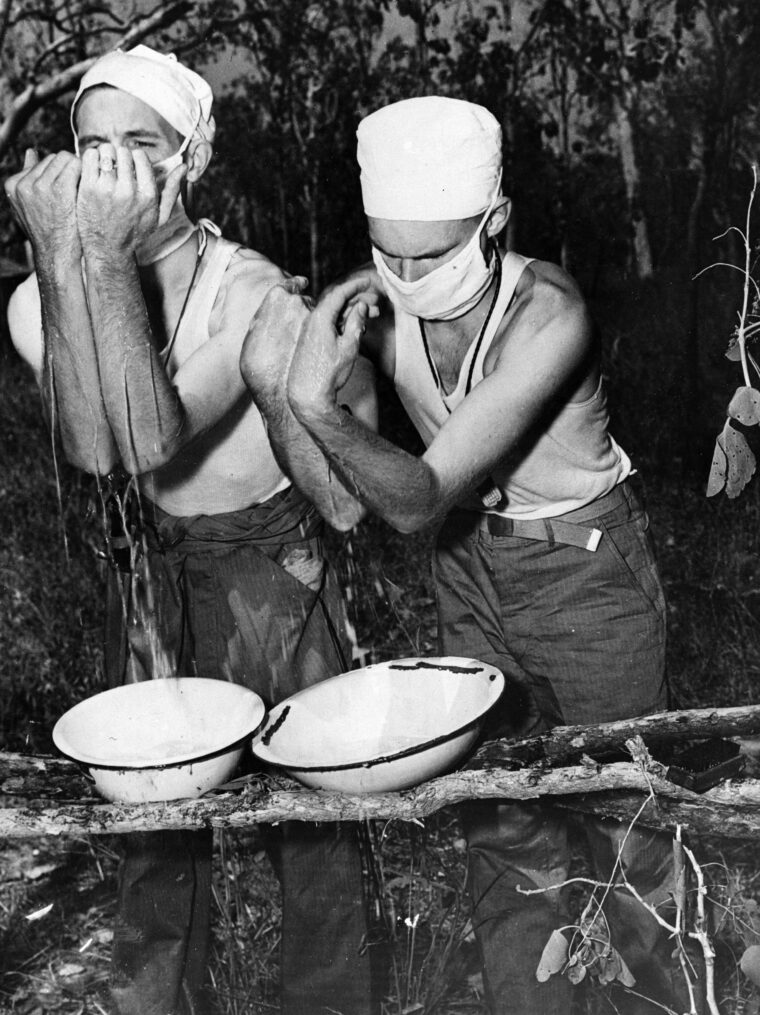

These spartan PSH tents were set up to accommodate major surgery, sometimes so close to the front that they were under fire from the enemy. They retreated or advanced rapidly with the fortunes of war. A staff of a fully equipped PSH could disassemble and load tents, equipment, and personnel onto waiting trucks within two hours. When trucks proved unavailable or impracticable, pack mules or porters were used. PSHs were flown over the Owen-Stanley Range with the troops to participate in the battle of Buna. PSHs proved so successful that they were duplicated in every theater of war where Americans fought and they were an important link in the human chain that carried wounded soldiers from the battlefront back to the home front.

Respect for the Medic

The front line of the whole medical operation was known as the aid man or medic. The medic was not a trained physician, but he had extensive Army training in first aid. During boot camp the medics were sometimes subjected to ridicule by their gun-toting fellow grunts, but things changed in combat. Then the lowly medic was universally beloved by the soldiers.

The medic was the guy who lanced and patched up the blisters. He gave aspirin for head colds and watched over the purity of his unit’s drinking water. Cartoonist Bill Mauldin called him “the private soldier’s family doctor.” In combat he was the one expected to come to the rescue of his wounded comrades under fire. The pained cry of “Medic!” brought him on the run. It was the rapid response of the medic and his litter bearers under hazardous conditions, administering first aid, applying tourniquets, injecting pain-killing morphine, and rushing a casualty from the front to the rear hospitals that was responsible for saving many lives.

Mauldin chronicles one story about the medics in his book Up Front. The story centers on the combat badge that distinguished a frontline fighting soldier from the rear-echelon troops. It was a symbol of honor that earned a man his $10 a month combat pay, and the troops took pride in wearing it.

In one of those incidents that angers soldiers in wartime, these badges—and the extra pay they denoted—were taken away from frontline medics. The rationale was that under the conditions of the Geneva Convention medics were not to be frontline combat soldiers. The decision was ostensibly made for the medics’ own safety. Or so they thought. There was an immediate uproar from the troops. It came not so much from the medics as from their GI friends whose lives they had saved and in whose care they were entrusted.

One soldier offered the ultimate threat, “Wait’ll Ernie Pyle hears about this!” The generals got the message, and the combat badges were soon restored to the medics.

No one could fault the bravery of the aid man. By the end of the war five medics in the European Theater were awarded the Medal of Honor. Hundreds more won Silver and Bronze Stars.

Reducing Battlefield Fatalities

Ideally, the system of medical treatment was set up so that frontline medics would be able to treat a wounded man where he fell. This usually consisted of a shot of morphine to prevent him from going into shock, some sulfa powder to keep his wounds from getting infected, and a rapid bandage to stop the bleeding.

Then stretcher bearers were called forward to carry the patient from the field to a battalion aid station perhaps a kilometer behind the lines. At the aid station more thorough first aid could be administered, a diagnosis made, and a seriously injured man stabilized. From there, the wounded were carried or transported farther back to a collecting station that sorted out the more serious casualties for the PSH (if available) or sent the wounded to a clearing station that consisted of 12 doctors and 96 enlisted men.

The clearing station was far better equipped than the frontline medics, and major medical surgeries could be performed in sanitary conditions before the worst cases were sent to an evacuation hospital some 12-15 miles behind the lines. From there, the seriously wounded were shipped to a general hospital as near to the home of the individual soldier as possible.

Other patients stayed in the evacuation stations while they recovered. In these cases the staff tried to make the hospital as therapeutic as possible. Correspondent Raymond Clapper reported from the 171st Station Hospital in Port Moresby, New Guineaa: “Bright flowers are planted in gardens all around the hospital tents. Many of the boys are sent seeds from home … Patients work a 5-acre garden … Colonel Wilkinson [the commanding officer] picked a 15-pound watermelon outside his tent.”

Of course it was not always possible to be this organized, but it was a giant step for soldier care and comfort over any previous war. The mortality rate of wounded soldiers dropped from 8.1 percent in World War I to just 3 percent in World War II. During the Civil War the mortality rate had been as high as 25 percent.

Combatting Noncombat Deaths

Even more impressive than battle wound survival was the decline in noncombat deaths. The death rate from pneumonia fell from 24 percent to 6 percent between the world wars. This advance in medical capabilities was largely credited to new drugs and medications that, combined with rapid treatment, helped end the scourge of many diseases.

It turned out that only 585 U.S. soldiers died of disease out of 918,298 men treated. The odds of survival improved as the war progressed. In 1943, one in 700 military malaria patients died. By 1944, the figure was one in 14,000, an impressive record considering that nearly eight million American soldiers were involved in the conflict.

World War II was the war of the “miracle drugs,” and they were widely used. In the jungle areas, men threatened by malaria lined up daily for their dose of atabrine, even though it turned their skin a sallow shade of yellow. By the 1940s, atabrine was thought to be more effective than quinine for malaria patients.

Sulfa drugs were also extensively used to prevent infection by medics and doctors on every front. Penicillin shots were given routinely for the least little sniffle. Morphine was almost automatically administered to a battle-injured man from little syrettes, a kind of one-time-use syringe that held half a gram of the painkiller. Many deaths due to shock were prevented by this battlefield expediency, and more than one GI became addicted to the drug.

The art of making blood plasma from whole blood had been perfected. It was much easier to store and ship plasma than whole blood, and plasma went everywhere the Army went. But there were side effects from haste and unknown factors. Unlike whole blood, the plasma could be pooled, and soon hepatitis found its way into the entire supply. Army doctors quickly learned from their mistakes. In mid-war, after thousands of hepatitis cases, the plasma program was scrapped in favor of the now common blood bank. Civilians at home lined up to give blood for the boys overseas.

After the war, the use of the pesticide DDT was banned for its disastrous ecological side effects. However, it was used extensively during the war to combat insects and their diseases. Contemporary literature called DDT a “miracle drug,” and everyone sang its praises. Soldiers had their heads dusted with it to kill lice and other vermin. It was used everywhere in the world for mosquito abatement. The liberal use of DDT was even credited with stopping a typhus outbreak in Naples in January 1944, and it saved perhaps thousands of military and civilian lives. In a very real way, World War II doctors and soldiers thought of this cornucopia of drugs and medications as a giant advancement in the science of medicine. The worry about side effects did not enter the picture until the crisis of war was safely over.

The Army Medical Department Goes Island Hopping

As the scope of the war was worldwide, the Army Medical Department had to maintain duplicate operations in every theater. In the South Pacific, beginning in New Guinea and in the subsequent island-hopping campaigns the medical authorities were as much if not more concerned with disease-bearing bacteria, insects, and mosquitoes than they were with enemy bullets.

Jungle rot was a GI-inspired name used to include a variety of terrible and mysterious fungal skin diseases that soldiers contracted in the dense rain forests that covered tropical islands. Malaria, dysentery, typhus, and a number of other ailments sidelined more soldiers than did the whole Japanese Army. But battle casualties were high enough, and Japanese soldiers were subject to the same debilitating jungle diseases as Americans. The Japanese did not typically have access to care of the quality available to U.S. soldiers.

A single battle illustrates the effectiveness of the Army Medical Department. In the battle for Saipan, American combat casualties amounted to 3,000 killed and 13,000 wounded. Of the wounded, 5,000 were eventually returned to their units. From each amphibious campaign more was learned about how to treat wounded men in battle, evacuate them to the beach, and remove them immediately to waiting hospital ships for major surgery if needed. In the Pacific, valuable service was rendered to the Army Medical Department by island natives who carried supplies and equipment, labored tirelessly as litter bearers, and guided troops through the trackless jungle.

With Merrill’s Marauders

Supplies for the eastern Burma operations had to be flown over the “Hump” of the Himalaya mountains. Guns, ammunition, food, and gasoline all vied for space with medical supplies in crowded planes. From Chinese airfields the supplies were loaded onto trucks and driven in long convoys down the northern section of the Burma Road and finally loaded on the backs of Chinese coolies and pack mules to reach the front. Wounded soldiers moved in the opposite direction once the precious cargoes were unloaded.

In Burma, the same jungle diseases that tormented the soldiers in the South Pacific afflicted the fighters on both sides. Temperatures could reach 110 to 120 degrees Fahrenheit. One infantryman said, “You couldn’t tell where the sweat ended and the rain began.” Field hospitals were set up along the Burma Road. They improved in quality as the returning trucks drove farther north. As always the rule was that the farther a wounded soldier was from the front, the better the medical facilities.

Volunteer surgeons were flown to remote jungle bases by the ubiquitous Piper Cub aircraft to treat casualties of Merrill’s Marauders in Burma. On the return trip out of the jungle, the planes could accommodate one casualty each. Evacuation by air was typically reserved for the most seriously wounded. After Merrill and his men captured the Japanese airfield at Myitkyina, Dr. Gordon Seagrave, who later wrote the book Burma Surgeon, served the medical needs of the Marauders by flying into the thick of the fighting along with 10 of his personally trained Burmese nurses.

When Dr. Seagrave arrived at Myitkyina, the Marauders controlled only the airfield. Japanese troops still held the surrounding jungle and fired on the airfield at will. There were no tents to shelter the wounded, so Dr. Seagrave ordered that parachutes be stretched over poles to provide his nurses and patients some relief from the hot tropical sun and the frequent rains. The parachutes he commandeered had been used in supply drops to the beleaguered Allied troops, and each was brightly colored to designate its contents. Although the colors gave away his hospital’s position, Dr. Seagrave figured that the Japanese already knew where they were. Shade was more important than camouflage.

When wounded men were ready for evacuation from eastern Burma and China, they were flown over the Hump in specially designated Douglas DC-3 aircraft staffed by women known as air-evacuation nurses. These women were reportedly chosen from among prewar airline flight attendants who had experience in remaining at ease in all kinds of flying conditions. Medical training was secondary.

Respecting the Red Cross

The Pacific Theater held many dangers for medical personnel. The famed Red Cross symbol used by all doctors and medics was not one that the Japanese regularly treated with respect. Japan had not signed the Geneva Convention before the war and did not feel obligated to abide by the international rules of conduct toward medical personnel.

The easily recognized red and white emblem of the International Red Cross was no guarantee of safety. Medics and litter bearers were killed and maimed on every front. American medical crews quickly learned to smear mud over the red and white symbol emblazoned on their tents, helmets, and trucks to prevent themselves from being more of a target than they already were. In New Guinea, American doctors attached to the PSHs were given target practice with M-1 carbines when some of their noncombatant colleagues were killed by the enemy.

German soldiers usually respected the corpsmen and the Red Cross, but not always. Medics were killed all over Europe. Allied soldiers, however, were not always scrupulous with German Red Cross men either, and many of them fell in combat to American bullets.

Captured doctors of both sides were put to work by their enemies. There were many cases of German doctors who had been taken prisoner working on Americans and captured American doctors given German wounded to care for. As a rule, captured physicians were treated as respected colleagues by their counterparts. One American doctor reported that he and German physicians freely taught and learned different medical procedures from each other. The American medical corps generally provided the same care to wounded German prisoners as to Allied casualties.

Diseases and Injuries of the Mediterranean Campaign

During the North African campaign, the threat of disease was not as severe as it was in the Pacific. Still, desert insects, snakes, and bugs could be just as dangerous as their jungle cousins. Medical corps personnel learned a great deal in North Africa while treating combat casualties, and they utilized that knowledge during the fighting in Europe.

The Italian campaign brought new lessons and refinements to standard medical procedures. A dentist invented a way to keep a soldier’s neck in traction by using a plate that fit the roof of the mouth and then was tied off to the stretcher. This saved time for the frontline doctors who previously had to immobilize an injured soldier in a cast before moving him to the rear.

In any war venereal disease can become a major problem. Signs and lectures warning the troops about the curse of VD were common but never completely effective. In Italy, as elsewhere, special prophylactics stations were set up by the medical department to distribute condoms to the men. These stations were refereed to as “pro stations.” However, when the Army Public Relations Office (PRO) set up shop in Italy to accommodate the growing number of civilian press who wanted to cover the war, its acronym PRO confused more than one soldier who walked into the Public Relations Office seeking condoms.

Massive Medical Preparations for D-Day

Perhaps the biggest challenge faced by the Army Medical Department during the war was the buildup for the battle on the beaches of Normandy. Heavy casualties were expected during Operation Overlord. All the experience and lessons learned in the amphibious landings of the Pacific as well as in North Africa, Sicily, and Italy were applied during the planning of the largest invasion the world had ever seen.

In England, 97,400 hospital beds were designated for casualties. In total, accommodations for 196,000 patients were prepared. Eight thousand doctors and 10,000 nurses were tapped to care for the wounded. There were 800,000 pints of blood plasma stockpiled. As many as 600,000 doses of penicillin were readied for the invasion, with another 600,000 to be ready during the month following the June 6, 1944, landings. Fifteen hospital ships and 50 dedicated Red Cross airplanes capable of carrying 18 severely wounded men on cots were prepared. Landing craft were often laden with wounded for the return trip to England after disgorging their cargoes of supplies and vehicles on the beaches of Normandy.

Overall, the plan worked, but there were difficulties at times. The carbon monoxide of vehicle exhaust often permeated the tank decks of transports when wounded men were brought aboard and laid down where tanks had rested so recently. The walking wounded were sent on deck, weather permitting. Rough seas were a factor in the weeks after D-Day, and storms tossed men who were already in pain.

When the transports reached English waters, patients were usually transferred to smaller craft and landed on empty beaches so that the wounded would not have to disembark at the main ports, which could add to the confusion at the overworked docks. It was considered important to have only outbound traffic at the crowded port facilities, which were overflowing with men and material headed to France.

The returning wounded were carried onto the smaller boats, which then headed for a beach landing where ambulances and medical personnel would be waiting. The ships bringing wounded often had to wait for the proper tides before landing. In the early days of the invasion, it could take as long as 14 hours for a man to reach a hospital in England. From England, wounded American and Canadian soldiers sailed home aboard specially designated and fully equipped hospital ships that could carry up to 500 men each. The ships housed complete operating and surgical facilities.

Medics arrived in Normandy on D-Day, right along with the troops. By D+1 field hospitals were being set up on the beach. By June 10, the first nurses arrived, and in early July fully staffed surgical tent hospitals in Normandy were capable of performing 15 surgeries at once.

Treating the Wounded in the European Theater

Although casualties from the invasion of Europe were not as high as feared, there were still thousands of them. Alongside battle casualties, field hospitals often found themselves treating cases of “psychoneurosis” or battle fatigue. Rest and care restored most of these patients to their units, but a few men suffered more severe mental disability and were sent home to hospitals for long-term care.

The surgeon general commented, “There is nothing mysterious about psychoneurosis. It does not mean insanity. It is a medical term used for nervous disorders. It manifests itself by tenseness, worry, irritability, sleeplessness, loss of self-confidence or by fears or over-concern about one’s health … Some of our most successful business and political leaders were psychoneurotic.”

As well prepared, equipped, and manned as the field hospitals were they could be overwhelmed by the sheer volume of casualties produced by modern warfare. An officer of the 171st Station Hospital remarked, “Four days after we were given this real estate (in Port Moresby), which was covered with high kunai grass, we had 500 patients.”

In Bastogne, during the Battle of the Bulge, the aid station of the 101st Airborne Division became a field hospital with no way to evacuate the wounded. The hard-pressed corpsmen soon ran out of morphine, plasma, and bandages. These had to be air dropped into the enclave. A call went out for surgeons, and some hearty volunteers flew into Bastogne by glider to perform emergency operations.

Throughout the Battle of the Bulge, soldiers on both sides suffered terribly from the cold of the winter offensive. Trench foot was more common than combat wounds. The 77th Evac Hospital was equipped for a maximum of 750 patients. During the Bulge it received twice that number.

Returning Home

The final link in the chain of wounded men flowing back from the front was the arrival home. The Army Medical Department did not see its job as complete when severely wounded men arrived stateside. Men newly blind, deaf, or with loss of limb needed rehabilitation. Hospitals and vocational programs were set up and staffed for the thousands who required additional help in retraining for civilian life.

Today, the programs of the Veterans Administration are taken for granted and even expected for wounded soldiers. They were innovations of the 1940s, and thousands of men went through rehabilitation.

A curious duality exists in the military mind. On one hand increasingly destructive methods are being devised to kill and maim soldiers and civilians; on the other, great strides in military medicine are being made to save lives. If the Army Medical Department has a legacy, it is that the advancement of patient care and rapid response to injury have also improved peacetime medical care.

Glenn Barnett is a frequent contributor to WWII History. His father was commanding officer of the 23rd PSH in New Guinea.

I am writing a novel that has a scene of an airman shot down over the Neatherlands in July of 1942. In my story, he is badly wounded and a RAF Lysander flies to a farmer’s field where the airman is hiding with help from the Resistance and picks him up under moonlight.

I am trying to find out what air field in England this rescue Lysander might take him near a USAAC hospital that can care for his flak wounds. Please let me know if you have a airfield, the town nearby, the name of the military hospital he might go to. This is fiction, but needs an actual place to take the patient.

Thanks for your help.

Bill Carmichael

[email protected]