By Kelly Bell

Confederate soldiers bitterly called it “that damned Yankee carbine they load on Sunday, and then fire all week.” This seven-shot lever action gun was indeed the first rapid-firing, repeating firearm to make a significant difference on the battlefield. The Confederacy did not have time to devise anything to match it, and captured guns were rarely of use because a shortage of copper made it impossible for the southern states to manufacture ammunition for the Spencer carbine. This gun was strictly a servant of the Union, and it performed with devastating effectiveness.

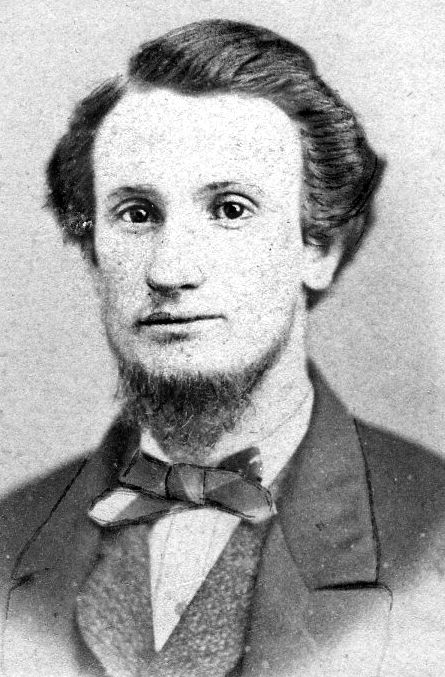

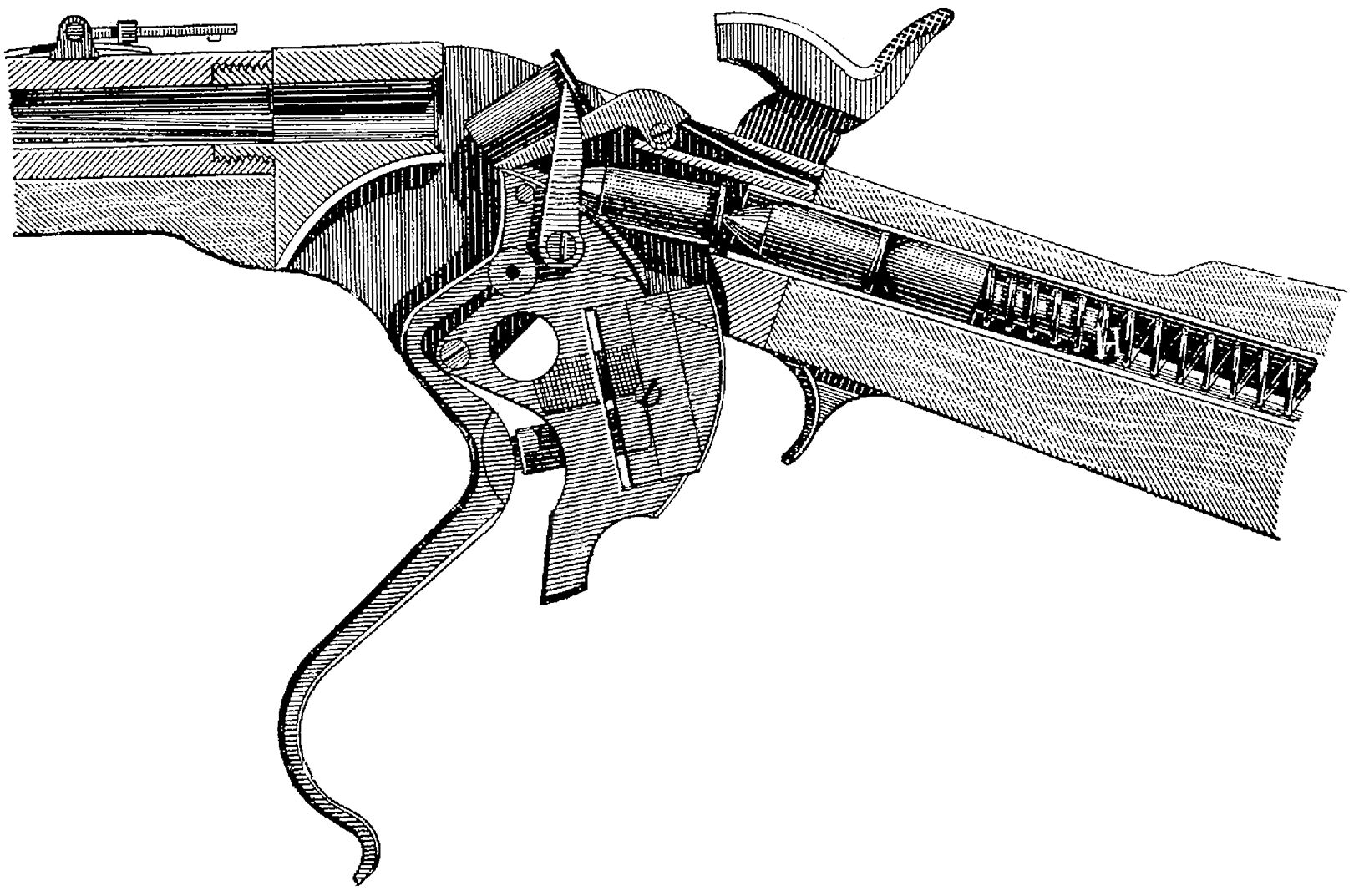

In 1860 27-year-old inventor Christopher Spencer was a machinist employed in Hartford, Connecticut by the Sharps Rifle Company. Working on his own time he perfected the revolutionary shoulder arm that bore his name. The Spencer carbine consists of a wooden shoulder stock with an integral straight grip, metal receiver, wooden forend and a long-running section of exposed barrel with three barrel bands joining it to the forend. The external hammer is offset to the right (to the consternation of left-handed shooters.) There is a flip-up sight ahead of the receiver, with a standard front sight just aft of the muzzle. The trigger is beneath the grip handle, and the lever doubles as a trigger guard. Sling loops under the shoulder stock and second barrel band permit attachment of a shoulder strap. Barrel lengths of various models of the rifle ranged from 20 to 30 inches.

The gun is chambered for the unique .56-56 rimfire cartridge, which is loaded through the gun’s butt and fed from a seven-round internal tube magazine located in the buttstock. The magazine tube is spring-loaded at its rear, with the cartridges aligned in single file and fed into the firing chamber in turn. The magazine is locked into place within the butt by a rotating release/catch that must be positioned 90 degrees off center for removal of the tube. By working the lever the shooter reloads the chamber while simultaneously ejecting spent casings downwards. The hammer is manually cocked. After familiarizing themselves with the gun, soldiers could consistently maintain the then-revolutionary firing rate of 14 to 20 rounds per minute. The Spencer’s muzzle velocity of 1000 feet per second not only gave it impressive stopping power, but an effective range of 500 yards–a substantial battlefield reach.

After patenting his design in 1861 Spencer lobbied hard, long and ultimately successfully to introduce his gun to the Federal military. He first arranged to sell a contract to the U.S. Navy in June 1861 after carrying out a demonstration for Commander John A. Dahlgren, who looked on with growing enthusiasm as the inventor fired his gun after burying it in sand, immersing it in salt water and, over the course of the two-day trial, firing a carbine 250 times without cleaning it and with no drop-off in accuracy. Due to limited funds, however, and the fact that rifles are not in great demand during naval battles, Dahlgren ordered just 700 of Spencer’s carbines.

Word of this new weapon was beginning to spread, though. Federal General James H. Wilson had also attended the demonstration, and in a letter to the Union Army’s chief of ordnance he gushed, “There is no doubt that the Spencer carbine is the best firearm yet put into the hands of the soldier, both for economy of ammunition and maximum effort, physical and moral.”

A few Federal units fighting at the battle of Antietam had just been issued Spencers, and despite the rifle’s performance being generally laudable some troops reported having trouble with its extractor, causing jamming. Spencer acted immediately to address this problem, and swiftly corrected it.

Finally, on August 18, 1863, he managed to secure a personal audience with President Abraham Lincoln. When the president bench-fired the rifle in a vacant lot outside the White House he was impressed. Lincoln fired seven rounds into a wooden board at 40 yards, hitting the crude bull’s-eye with the second shot. His only complaint was that the carbine had to be removed from the shoulder between shots in order to cock the hammer. Otherwise he had nothing but praise, and presented a piece of the shattered board to Spencer as a memento. For the rest of his life this was the inventor’s prized possession.

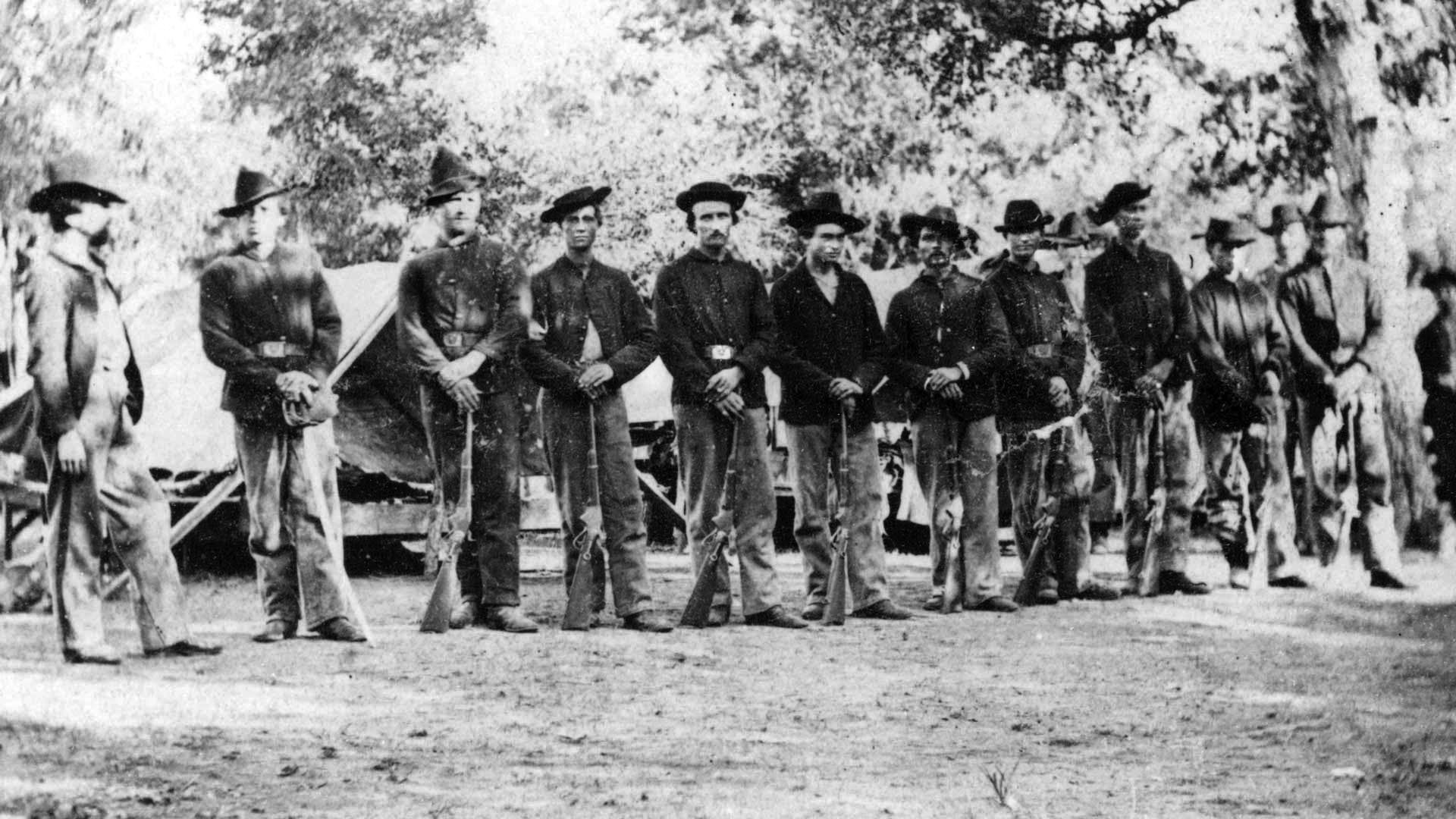

Following this presidential endorsement the Union Army purchased 13,171 Spencer carbines and set up facilities to manufacture its distinctive ammunition. Adoption of the rifle was unavoidably delayed because manufacturing plants had to be constructed. The tide of battle had already turned against the Confederacy before the Spencer’s widespread introduction, and most Federal forces continued to use older arms. Still, this new carbine was a huge technological leap, and hastened the war’s end. Union commanding General Ulysses S. Grant called it “the best breech-loading arm available.” By the end of hostilities 100,000 had been manufactured. This number was too small for the gun to have made the impact of which it was capable. Some officers and enlisted men, unwilling to wait for slow, small deliveries, personally purchased the rifle, paying for it out of their own pockets.

By the time the Spencer began circulating within the Federal military the War Department already had outstanding orders for 15 different patterns of breech-loading weapons, some of which (especially the Henry) had also been favorably tested. Like Christopher Spencer, most of these inventors and small-time manufacturers had little in the way of production facilities. This was especially significant considering the wartime demand for firearms. The officials in the War Department had a hard time deciding which weapons deserved the lion’s share of production consideration. Lincoln’s bench rest test of the carbine belatedly tipped the scales in its favor. Prior to the presidential endorsement there had been a surprising amount of resistance to this new arm.

The gargantuan expense of the conflict had compelled the men in the War Department to be penny pinchers. Unlike Lincoln they had never fired this weapon and were ignorant of the tactical implications of its adoption. By reading its specifications they did, however, learn that it was heavy. It weighed in at over ten pounds when loaded (on the plus side this weight cut down on recoil.) It also required specialized ammunition not yet available through regular ordnance channels. Most significant for the bean-counting officials, though, was the cost. Standard price for a musket (easy to manufacture, lightweight, accurate, with abundant ammunition and easy to repair) was about $18. Spencer’s new gun cost $40. Adding an attachment for a saber bayonet hiked the tag to $43. There were other factors contributing to the slowness of the carbine’s general adoption by Union forces.

Detractors pointed out that troops using this rapid-fire repeater would tend to use up their stores of ammunition quickly (a problem that bedevils armies to this day,) and be left holding empty guns for the bulk of the battle. Also, there was the problem of the clouds of smoke the cartridges’ black powder would produce. Unless there was a stiff breeze billowing smoke from the multitude of discharges would build up and blind the shooters. These would indeed prove to be valid points, but the carbine’s positives outweighed them.

Lincoln’s first commander, General George McClellen, was an early convert to the rifle, and convinced the Army to order 10,000 Spencers. This was far too few to make a significant impact on the war’s course, so Spencer sought out the prestigious General Hiram Berdan, commander of the 1st and 2nd Sharpshooters Divisions and a renowned rifleman. In December 1861 Spencer had sent a carbine to Berdan for testing. At first the tryout went well, but after firing several shots Berdan chambered a defective round. The cartridge rim exploded, blowing hot gas back into the famed marksman’s eyes. Basing his evaluation of the gun on that one faulty bullet rather than the carbine’s overall performance and potential, Berdan left it on the bench rest and stalked off in a huff to order Sharps rifles for his command.

Although a brilliant inventor, Spencer was not a businessman. His newly formed Spencer Repeating Rifle Company was in danger of folding. New Secretary of War Edwin Stanton, however, renegotiated the firm’s contract with the Army, allowing it to continue operations at a slower pace, gradually building up sufficient stocks to arm a significant percentage of the Union’s troops. Spencer tirelessly toiled to open new production facilities and hire (or train) skilled workers while also designing and overseeing the building of construction equipment to make the rifle. By March of 1863 Spencer’s main production facility on Tremont Street in Boston was a beehive of activity. In May the Massachusetts legislature ordered 2000 rifles to be issued to the state’s soldiers. All this and Lincoln’s endorsement the following August insured the carbine would see relatively widespread usage versus the Rebels.

Some of the Federal units fighting at Gettysburg had just received shipments of the carbine, and used them with devastating effectiveness. On July 1, 1863 General John Buford’s cavalry units used the Spencer to shoot down successive waves of Confederate infantry. The following day General John Geary’s outnumbered troops shouldered their new guns and repulsed an entire division of charging Rebels. One unnamed Union officer later described the carbine’s effect on the mass of fanatical gray-clad soldiers.

“The head of the [Confederate] column, as it was pushed on by those behind, appeared to melt away or sink into the earth, for though continually moving it got no nearer.”

This was not the first time.

In the battle of Hoover’s Gap in Rutherford County, Tennessee on June 24-26, 1863 Union General William Rosecrans, commander of the Army of the Cumberland, thwarted Confederate General Braxton Bragg’s hopes of lifting the Federal siege of Vicksburg by fighting off repeated attempts to break through the Yankee lines. Using just-delivered Spencer carbines Rosecrans’ troops held the line and insured General Ulysses S. Grant overwhelmed Vicksburg’s garrison, thus winning for the Union control of the Mississippi, splitting the Confederacy and isolating Louisiana, Arkansas and Texas and their vast reservoirs of men and material from the rest of the Rebel states fighting in the main theater of operations to the East. Had Rosecrans not had the Spencer in this one battle the implications for the war as a whole are sobering.

During the battle of Chickamauga the following September, Union troops armed with the Spencer thwarted Bragg’s efforts to secure the pivotal main road to Chattanooga on the battle’s first day. The following day Confederate General James Longstreet’s assault on the Federal line came to grief under the withering firepower of Colonel John Wilder’s Spencer-armed Indiana “Lightning Brigade.” Aside from taking a heavy toll of men shot down, Wilder’s unit with its state-of-the-art weaponry made so much racket that it deceived Longstreet into thinking he was facing a force much larger than a solitary brigade. This resulted in his movements being rather tentative and slow, buying time for other Union elements to deploy.

“Hoover’s Gap was the first battle where the Spencer repeating rifle had ever been used,” said Wilder. “In my estimation they were better weapons [than any] that have yet taken their place, being strong and not easily injured by the rough usage of Army movements, and carrying a projectile that disabled any man who was unlucky enough to be hit by it.”

As the war progressed and more Federal outfits received the Spencer the gun played an increasingly prominent role. By war’s end approximately 100,000 Spencer carbines were in use. Had the gun been adopted sooner the Confederate states might well have been forced to surrender considerably earlier.

During the 19 November 1863 battle of Olustee a Captain Ford of the 1st Georgia Regulars came up against the Spencer-equipped 40th Massachusetts Mounted Infantry. Ford later described the Massachusetts soldiers as, “hard to move, as they seemed to load with marvelous speed and never had their fire drawn.”

![On the back of his sketch of the Battle of Darby Town Road, artist William Waud wrote “Friday 9th attempt of the Rebels to turn our right flank. The fighting was done in thick woods. Our men shewn[sic]in this sketch are armed with the Spencer Rifle.”](https://warfarehistorynetwork.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/M-Win24-Weapons-Spenser-6.jpg)

Determined to learn what kind of marvelous firearm his foes were using, Ford had his men concentrate all their fire on a solitary, isolated Yankee soldier, killing him just so they could capture and examine his gun. This Spencer turned out to be the most prized battlefield trophy ever taken by the 1st Georgia Regulars.

By late 1864 Federal units armed with the carbine had been using it long enough to have become familiar with it and expert in its usage. During the battle of Nashville from December 15-16 Spencer-armed Union forces commanded by General George H. Thomas routed and virtualy destroyed the outgunned Confederate Army of Tennessee under the highly regarded generals John Bell Hood and Nathan Bedford Forrest.

The following April, in one of the last major battles of the War for Southern Independence, General Wilson saw his early support for the rifle confirmed when he divided his 13,500 Spencer-carrying troops into three columns and set them on Forrest’s 5000 men manning the defenses around Selma, Alabama. Armed with an ad hoc assortment of muskets, pistols and shotguns the old men and young boys of Forrest’s command never had a chance versus the waves of bluecoats bearing down on them while pumping out massses of copper bullets. On 2 April Wilson secured Selma, losing just 359 men while killing 2700 hapless Rebels. It was a bloodily fitting testament to the gun’s contribution to destroying the Confederacy. Days later General Robert E. Lee surrendered. War’s end, however, did not see the end of the Spencer carbine’s military use. It made itself felt in the Far West, Far East and Europe.

When the Cheyennes and the Oglala Sioux went on the warpath in the late summer of 1868 General Phil Sheridan took into account his positive experiences with the Spencer during his campaigns versus the Confederates. He made sure his men were armed with the gun when they rode into the war zone in the Kansas-Colorado border area. On 17 September a small detatchment of 50 cavalrymen blundered into a mixed force of 600 to 700 Sioux and notoriously militant Cheyenne “Dog Soldiers” in western Kansas.

The tribesmen chased the little band of soldiers across the state line into Colorado, where the troopers dismounted and frantically dug in on a small island in the nearly dry Arikara Fork of the Republican River. Cheyenne Chief Roman Nose expected to quickly mop up this handful of bluecoats, and immediately sent a massed mounted charge against the island. Both he and his men were shocked at the volume of fire coming from the tiny enclave of whites. When withering volleys broke up the first charge Roman Nose immediately sent a second, which likewise came to grief.

Roman Nose did not participate in the first two charges because he had learned his protective medicine was broken because he had recently eaten bread touched by a metal fork. After the second failed charge a warrior with the ironic name of White Contrary began taunting Roman Nose, accusing him of cowardice. Fearing for his reputation among his men more than he feared death Roman Nose mounted his pony and led the next charge. As he bore down on the defensive perimeter a copper round slammed into his chest, killing him.

Ruefully abandoning direct assaults the warriors settled into siege positions. For a week they kept up the pressure while the dwindling, hungry soldiers lived on meat from dead horses and dug in the sand for muddy water. Still, they held their attackers at bay with fatally accurate repeating gunfire from their trusty carbines. Early in this protracted battle two couriers slipped through the Indians’ lines under cover of darkness and rode 90 miles to Fort Wallace. On September 25 a relief column arrived and lifted the siege just as the defenders were running out of ammunition. Had it not been for the Spencer carbine there would have been nobody left to rescue.

Although Sheridan’s troops had been issued Spencers, most U.S. Army units fighting the Plains Indians following the War Between the States were armed with the Springfield single-shot rifle. This gun appealed to the Army brass because of its long range and the fact that, being a single-shot, troops armed with it would expend less ammunition that those bearing repeaters, and postwar budget cuts meant the Army could only afford to spend so much on bullets. To their disgust the troops serving on the western plains often found themselves facing warriors armed with the quick-firing Spencer carbine, which unscrupulous white traders were eager to barter to them in exchange for prized buffalo hides. Many of Lt. Colonel George Armstrong Custer’s troops (perhaps including the “Boy General” himself) went down under the sights of Sioux-aimed Spencers at Little Bighorn. Some of the hapless natives mowed down at Wounded Knee in 1890 were defiantly carrying Spencers. The gun’s battlefield use was not limited to North America, either.

With the Spencer carbine still in production after the Confederacy’s defeat the U.S. government sought out new markets for this splendid firearm, selling large quanities to the French for use in the Franco-Prussian War of 1870-1871. Although Frenchmen used the gun to take a heavy toll in German blood, France went down to sound defeat.

John Wilkes Booth was carrying a Spencer when he was caught and killed.

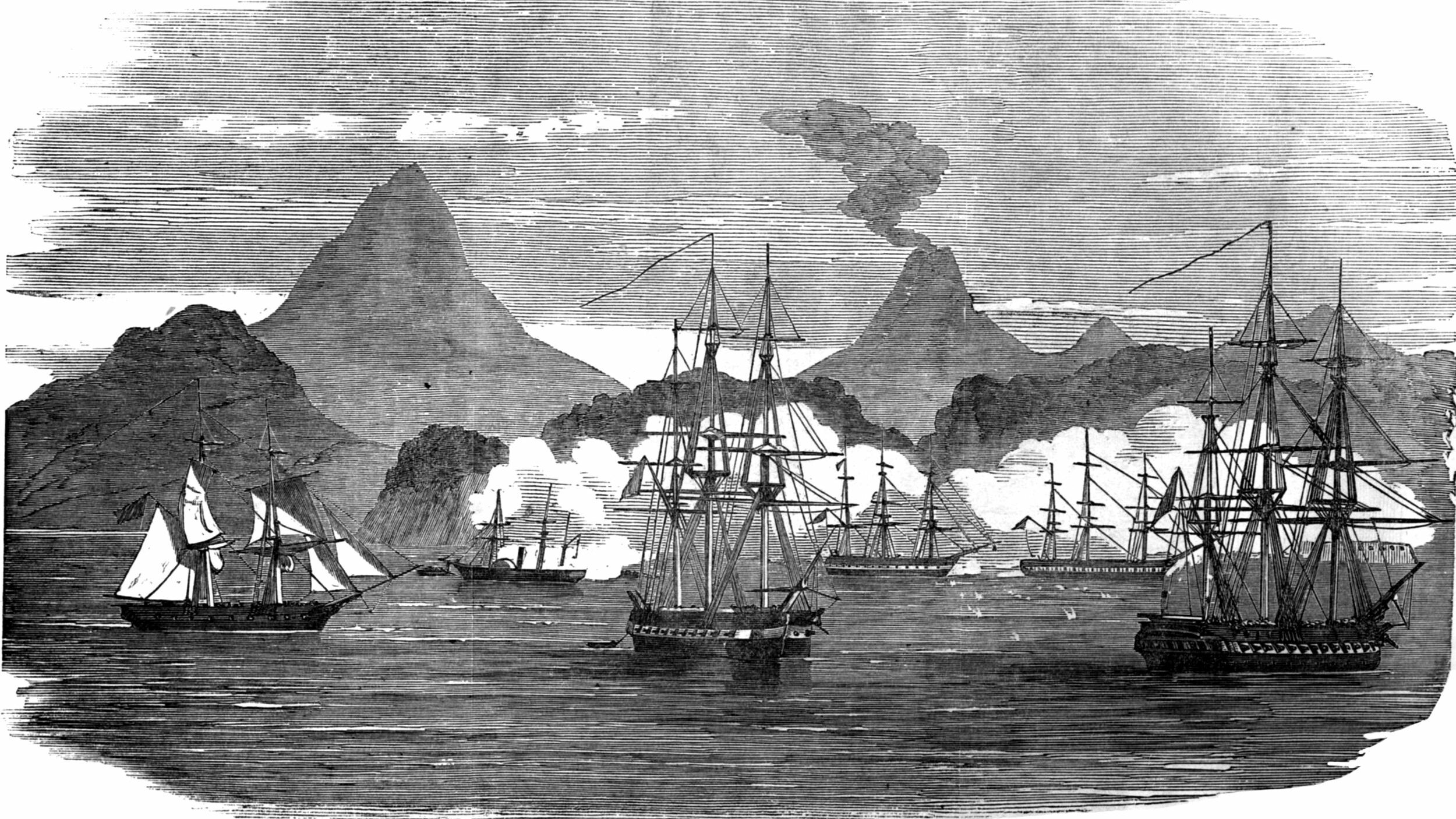

The rifle even made it as far as Japan, where soldiers bore it into battle during the Boshin War of 1868-1869, which ended the age of the Shogun. Imperial troops from Japan’s Tosa Province used the Spencer to devastating effect in the successful effort to end the rule of warlords and return the emperor to power. Yet even the Spencer’s technical excellence and success could not save its manufacturer from the vagaries of finance.

Following the close of the Civil War and the end of military orders the demand for the Spencer carbine dried up in a postwar America with a glut of the guns. Civilian sales were insufficient to maintain the Spencer Repeating Rifle Company’s solvency, and the firm sank into bankruptcy in 1868. Spencer sold out to the Fogarty Rifle Company, and in 1869 the Winchester Repeating Arms Company purchased the Spencer assets, but did not continue production of the carbine.

The Spencer Carbine’s legacy makes itself felt to this day as collectors buy and sell models for exorbitant sums. Hardly surprising considering the impact this weapon made on 19th Century warfare and history.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments