By Blaine Taylor

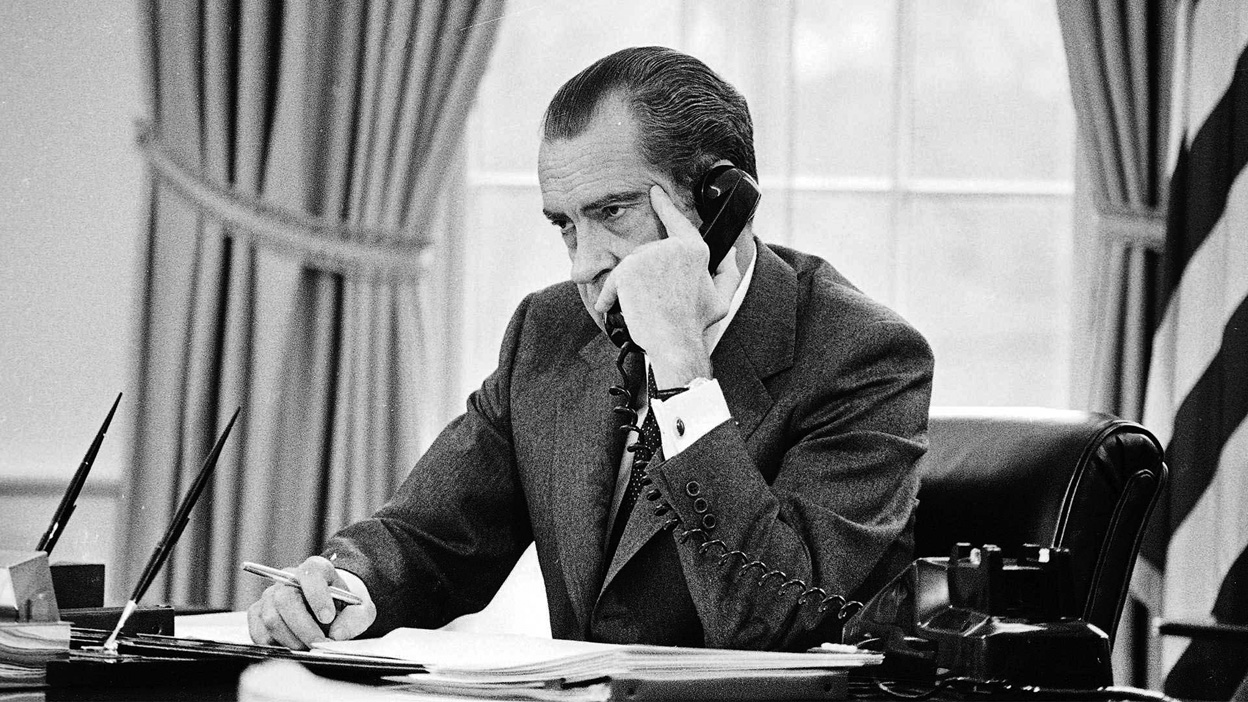

In the spring of 1974—at the height of the political Watergate crisis in Washington, D.C.—Joseph Laitin, a spokesman at the Office of Management and Budget whose office was in the Eisenhower Executive Office Building, next door to the White House, was on his way over to the west wing of the White House to meet with Treasury Secretary George Schultz.

“I’d reached the basement, near the situation room,” he later recalled, “and just as I was about to ascend the stairway, a guy came running down the stairs two steps at a time. He had a frantic look on his face, wild eyed, like a madman, and he bowled me over, so I kind of lost my balance.

“Before I could pick myself up, six athletic looking young men leapt over me, pursuing him. I suddenly realized that they were Secret Service agents, [and] that I’d been knocked over by the President of the United States.”

This bizarre episode appeared in The Arrogance of Power: The Secret World of Richard Nixon by British author Anthony Summers.

Returning to his office, Laitin recalled, “I sat there stunned, and I thought … ‘That madman I have just seen has his finger on the red button.’ I had a number for Defense Secretary James Schlesinger, a phone that only he could answer.

“I called him, and I asked if the president could order the use of atomic weapons without going through the Secretary of Defense.

“I said, ‘If I were in your position, I would want to know who the nearest combat-ready troops were who would respond to the president’s wishes to surround the White House. I would want to know what the next nearest combat-ready division was, that could not only be able to overcome them, but also respond only to the chain of command.’

“Then there was just a click at the other end, as the Secretary of Defense hung up.”

For his part, Secretary James Schlesinger recalled what then Chief of Naval Operations Admiral Elmo R. Zumwalt had told him of what Nixon had asked of the Joint Chiefs of Staff the previous Christmas, to determine, if in a crunch, “there was [military] support to keep him in power,” presumably even after an impeachment by the U.S. House of Representatives and a later trial by the U.S. Senate to convict him of “high crimes and misdemeanors.”

This, then, is the inside story of what allegedly happened, might have occurred, and in actuality played out, leading up to the resignation of President Richard M. Nixon on August 9, 1974.

In July 1974, Schlesinger asked for a meeting with the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs, Air Force General George Brown. “I told him,” Schlesinger said, “that every order that would come from the White House had to come to me directly, immediately upon receipt … that there were not to be any extraordinary measures taken.”

Brown later confirmed this: “Could the president get an order down to the end of the military establishment without our knowing it? The normal process would prevent any such happening because troop orders must go to a high Pentagon command center. I would have it in two minutes, and I’d be in the secretary’s office in 30 seconds,” he recalled.

In addition, Navy Admiral James Halloway—who had just succeeded Zumwalt—also remembered the scene: “Brown’s hands were shaking. He told us, ‘I’ve just come from the office of the Secretary of Defense. I made some notes. I want to read them to you.’

“What the Secretary wanted was an agreement from the Joint Chiefs—all of them—that nobody would take any action or execute any orders, without all of them agreeing to it. General Brown said they were afraid of some sort of coup involving the military.… We almost fell off our chairs. If anyone was thinking of a coup, it was not anyone in uniform. None of us wanted to conjecture on, ‘What if we get a screwy order from the President?’

“We knew it would take care of itself. We had in the Joint Chiefs five people with an average of 40 years’ experience, and they are picked for their good judgment…. They would have found a way to make sure that the right thing happened.”

The right thing under the National Security Act was that all military orders go from the president through the secretary of defense to the Joint Chiefs of Staff, and then on down the military chain of command.

Noted Schlesinger, “I did assure myself that there would be no question about the proper Constitutional and legislative chain of command—and there never was any question.” What he was referring to was the hierarchy of the elected Congress of the United States, the upper house of the Senate, and the lower of the House of Representatives.

Nevertheless, the secretary of defense still had two main concerns: the Air Force and the commandant of the U.S. Marine Corps, the latter being General Robert Cushman. The Air Force in particular admired the president for the way he’d gotten the downed prisoners of war extricated under the Vietnam War peace agreement signed at Paris in March 1973.

As for Cushman, he had served as a brigadier general, as Vice President Nixon’s national security adviser in the Eisenhower administration, and later as deputy director of the CIA in the Nixon presidency. In the latter role, the general had been involved in providing CIA resources to Watergate burglar E. Howard Hunt.

Now, in the tension-filled summer of 1974 in the nation’s capital, Cushman had received the political appointment from the president himself as commandant of the Marine Corps and was thus also a member of the Joint Chiefs of Staff.

Recalled Schlesinger, “General Cushman … might’ve acquiesced to a request from the White House for action. The last thing I wanted was to have the Marines ordered to the White House, and then have to bring in the Army to confront the Marines. It would’ve been a bloody mess.”

To answer Laitin’s previously posed questions, the secretary reflected that the nearest available troops were both Marine units: the ceremonial drill team troops at their barracks at the Washington Navy Yard at Anacostia Flats and the Marine Officer Candidate School trainees at Quantico, Virginia, and both under the commandant’s direct command.

Then there was the Army’s own crack 82nd Airborne Division stationed at Ft. Bragg, North Carolina, which had been secretly brought to Washington early in the first Nixon administration to protect government buildings from mobs of antiwar demonstrators.

Of course, the president then and now could also draw on the nearby reserve and national guard troops of both Maryland and Virginia, but this would have taken time to call up, and, again, the twin Army divisions most likely would have been better bets.

In 1967, formal U.S. Army military police troops formed a protective cordon at the Pentagon that withstood attempts by anti-Vietnam War protesters to enter it, and to these forces, in the April 1968 riot, President Lyndon Johnson added National Guard troops. In October 1969, Nixon used U.S. federal marshals to withstand the national Mobilization Against the War, which also served to prevent a government takeover.

Probably the closest that the nation ever came to having active-duty troops fight former soldiers came in summer 1932, when U.S. Army Chief of Staff General Douglas MacArthur personally commanded troops that dispersed former World War I veterans at Anacostia Flats seeking money during the Bonus March. He did this, however, against the explicit orders of President Herbert Hoover.

Few today know that the marchers returned again when President Franklin D. Roosevelt simply invited the leaders to the White House and listened to their grievances, foregoing the infantry, cavalry, and even tanks that had been used previously.

Had Nixon ordered troops to defend the capital both from Congress and demonstrators in 1974, I believe that he could, indeed, have gotten them to Washington, with or without Schlesinger’s approval. The president would have fired his defense secretary, and the Joint Chiefs of Staff would have acquiesced.

Once in the District of Columbia, however, problems would have arisen. The Kent State shooting of students by Ohio National Guardsmen on May 4, 1970, were still fresh in everyone’s minds.

Told to fire, they might well have balked. No officer—and, indeed, no appointed official—would ever have wanted to force that issue.

That is all mere speculation. What we do know follows.

In the second volume of his overall trilogy of memoirs, former Secretary of State Dr. Henry A. Kissinger recalled in 1982, regarding the run-up to Nixon’s planned resignation from office,“On August 2, 1974, he [former deputy and then White House Chief of Staff Army General Alexander M. Haig, Jr.] told me Nixon was digging in his heels; it might be necessary to put the 82nd Airborne Division around the White House to protect the President.

“This I said was nonsense; a President could not be conducted from a White House ringed by bayonets” apparently forgetting the American Civil War example of Abraham Lincoln during 1861-1865, with which history buff Richard Nixon was himself most familiar.

“Haig said he agreed completely…. He simply wanted me to have a feel for the kind of ideas being canvassed.” Or was Haig in reality acting as a lightning rod for the president himself, seeing whether or not Secretary of State Kissinger would concur in such an unusual usage of American military power? This basic question still remains four decades later. It also should be noted that it was the same Haig who first sounded out Vice President Ford about the possible granting of a presidential pardon for the ousted Nixon if the president would agree to resign. Haig also was the key man in the transition period between the pair of Republican presidencies.

During the Nixon-Ford era, Haig progressed from being Kissinger’s assistant to becoming White House chief of staff, along the way garnering ranks from colonel through four-star general, skipping that of lieutenant general altogether. None was a combat command. Haig had become a political soldier in the main.

In 2000, Schlesinger said, “The end of the Nixon presidency was an extraordinary episode in American history. I am proud of my role in protecting the integrity of the chain of command. You could say it was synonymous with protecting the Constitution.”

Brown agreed with his former boss. “The secretary had a responsibility to raise these sort of matters.”

What was the risk of a countercoup led by Nixon to ensure he remained in office?

Let’s examine the Watergate crisis from another perspective, that of the known military aspects preceding it and the possible effects as it unfolded from both the Pentagon and the Nixon White House.

In their 1992 book, Silent Coup: The Removal of a President, authors Len Colodny and Robert Gettlin assert that Nixon himself had neither ordered nor initiated the cover-up of the affair. Both roles had been masterminded instead, they asserted—in chapter after detailed chapter—by the president’s White House counsel, attorney John Wesley Dean III, who wanted to expand his role in the administration by becoming head of all its covert operations.

The break-in of the Democratic National Headquarters itself at the Watergate complex had nothing to do with the files of former Kennedy-Johnson administration official Lawrence F. O’Brien, but was instead an attempt to recover the names of a prostitution ring that was run there in secret and that involved both high-ranking and well-known Democratic and Republican Party figures whose names Dean wanted to keep hidden.

Thus, Colodny and Gettlin assert, it was Dean who had initiated the cover-up—not to protect the president, but himself. When he couldn’t do both, Dean turned state’s witness for the federal prosecution team named by Congress to investigate the affair.

In March 1973—when the president accepted the resignation of his longtime White House Chief of Staff H.R. “Bob” Haldeman—he appointed in his place the deputy of his former national security adviser and later Secretary of State Kissinger, Haig.

According to Colodny and Gettlin, Haig came into office with his own private agenda in mind as well, part of it being that, in the future, he harbored presidential aspirations of his own.

In addition, on January 20, 1981, Haig became the first secretary of state (named by President Ronald Reagan) to have previously worn a uniform since General George C. Marshall in the Truman administration.

As the Nixon regime’s Watergate disaster unfolded, the authors believed that the general had also ingratiated himself with Washington Post reporter Bob Woodward, a former U.S. naval officer who had briefed him in the first year of the administration in the White House.

Thus, indeed, there was a connection between the two men—soldier and reporter—the authors correctly asserted, and they did know each other from their earlier military contacts.

Thus, the stage was set and all the characters assembled on it for the following scene, as described by Nixon in 1978: “There was a knock on the door, and Haig came in.

“Almost hesitantly, he said, ‘This is something that will have to be done, Mr. President, and I thought that you would rather do it now.’ He took a sheet of paper and put it on my desk. I read the single sentence, and signed it: ‘I hereby resign the office of the President of the United States.’

“It would be delivered in a few hours, at 11:35 am on the 2,027th day of my presidency,” to Secretary of State Kissinger.

The military had never entirely trusted Nixon, it emerged later. Fall 1970 was an important time for the Joint Chiefs of Staff, who determined at that time that Nixon was out of control, according to Colodny and Gettlin.

Despite his seeming instability, Nixon had, before he took office as president in 1969, begun to shift his thinking in regard to foreign policy to forge new relationships with United States’ Cold War adversaries, work to wind down the war in Vietnam, and attempt to stop bloodshed in the Middle East.

“He cultivated an image of anti-Communism because he found it useful, but privately was more flexible in his thinking,” they wrote.

Once in office, though, as president, Nixon followed a different course altogether. He ended the Vietnam War, bringing home most U.S. troops by the time he left office. In addition, he traveled to Beijing and Moscow, thus significantly reducing Cold War tension.

Forced from office as the first, and so far only, U.S. president to resign, Richard Nixon published several books afterward. He was never tried, convicted, or imprisoned, and died at his New Jersey home 20 years later, in 1994, a revered elder statesman.

Haig died in Baltimore at 85 in 2010.

More revelations may occur as time goes by, possibly altering what we now know or believe to be true.

I don’t know about this stuff. Haig was an obvious self-promoter, but I highly doubt Dean was the mastermind of the Watergate break-in. Nixon was no “revered” elder statesman that’s for sure. He did do some good things like opening up China (I guess that was a good idea?) and he created the EPA, something the corrupt SCOTUS wants to dismantle.