By Al Hemingway

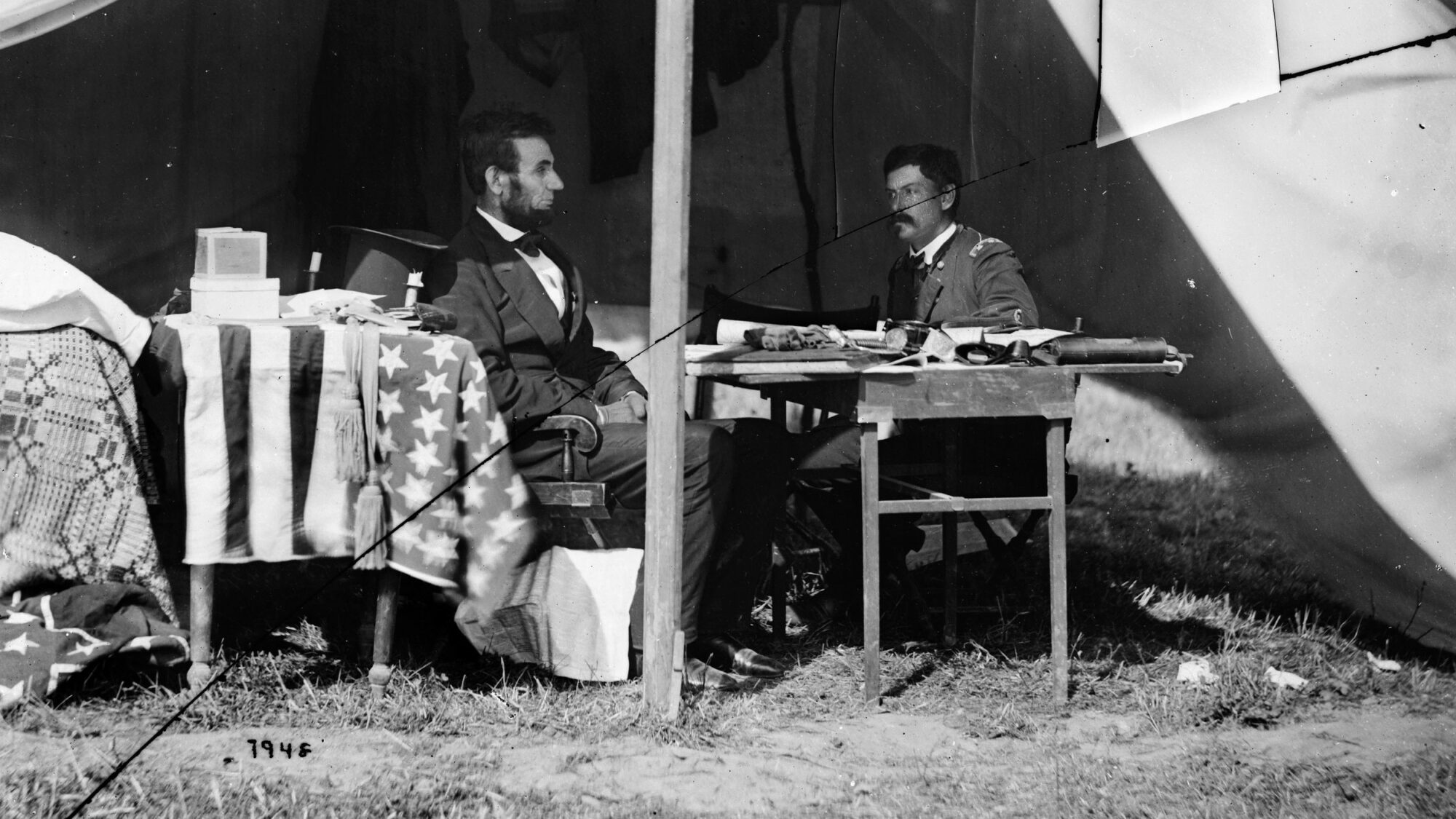

No two men were more different than Abraham Lincoln, 16th president of the United States, who came from a hardscrabble frontier background, and Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan, raised by well-to-do, influential parents in Philadelphia. The pair, despite their diverse backgrounds, would be thrust together by fate in a civil war that would change the nation forever.

In his new book, Lincoln and McClellan: The Troubled Partnership Between a President and His General (Palgrave MacMillan, New York, 2010, 252 pp., notes, index, photos, $27.00, hardcover), historian John C. Waugh examines this often shaky alliance and how it shaped the outcome of the war. Lincoln’s upbringing is well known to most Americans. Born in a log cabin in Kentucky, Lincoln’s mother died when he was young, and the family finally settled in Illinois, a frontier state at that time. A failure in business, Lincoln was a self-taught lawyer who, for the most part, learned his trade by riding the legal circuit, where he honed his courtroom skills. He won one term as a congressman, but his principled opposition to the Mexican War led directly to his defeat in the following election.

In his new book, Lincoln and McClellan: The Troubled Partnership Between a President and His General (Palgrave MacMillan, New York, 2010, 252 pp., notes, index, photos, $27.00, hardcover), historian John C. Waugh examines this often shaky alliance and how it shaped the outcome of the war. Lincoln’s upbringing is well known to most Americans. Born in a log cabin in Kentucky, Lincoln’s mother died when he was young, and the family finally settled in Illinois, a frontier state at that time. A failure in business, Lincoln was a self-taught lawyer who, for the most part, learned his trade by riding the legal circuit, where he honed his courtroom skills. He won one term as a congressman, but his principled opposition to the Mexican War led directly to his defeat in the following election.

Lincoln’s seemingly meteoric (but actually long-fought) rise began when he debated incumbent Democratic senator Stephen Douglas for the Illinois senatorial seat in 1858. Although he lost the election, Lincoln’s able performance in the debates propelled him onto the national political scene. With the help of a crafty behind-the-scenes convention team, Lincoln won the Republican nomination for president and was elected in 1860, setting the stage for the inevitable conflict with the furious South.

McClellan, on the other hand, had received the best education money could buy. Born into the upper crust of the city of Brotherly Love, he attended private schools. He later was accepted to the United States Military Academy at West Point, where he excelled, finishing second in his class. He proved himself on the battlefield during the Mexican War and was sent to the Crimea in the mid-1850s to study European combat tactics. His report on the subject was received with much praise. It seemed the young officer was on a bright career path in the military.

To everyone’s surprise, McClellan resigned from the Army to take the position of chief engineer for the Illinois Central railroad. His salary tripled that of an Army captain. Soon, McClellan was promoted to vice-president of the new line, with an impressive annual income. It was during these years when Lincoln and McClellan first met. Lincoln was an attorney for the railroad and the two spent time together between cases. McClellan would listen to Lincoln’s “rough-hewn” anecdotes, most of which he did not like. He immediately saw the “rail splitter” as socially inferior to himself, morally and intellectually—a value judgment that would come back to haunt McClellan.

When the war came, the Union was embarrassed by the Confederacy at the First Battle of Bull Run. McClellan, meanwhile, was winning victories in western Virginia and being hailed as the “Napoleon of the Present War” in the press. Lincoln summoned the general to Washington and presented him the command of the Army of the Potomac.

McClellan immediately set about rebuilding and reorganizing his troops, a task that he performed brilliantly. Morale within the ranks skyrocketed and the men were eager to fight—all except McClellan himself. He constantly argued for more reinforcements and additional artillery, becoming increasingly insubordinate to Lincoln, even keeping the president waiting while he was upstairs in his bed in Washington. Lincoln tolerated McClellan’s disobedient actions, believing that he would smash the Rebels and capture Richmond, ending the war.

Instead, McClellan was sacked after the ill-conceived Peninsula Campaign of 1862 and was replaced by Maj. Gen. John Pope, who was promptly thrashed at the Second Battle of Bull Run in the spring of 1862. With no one else to choose from, Lincoln reluctantly reinstated McClellan and, in September 1862, the two sides clashed at the bloody Battle of Antietam. When McClellan failed to aggressively chase General Robert E. Lee and badly weakened his army, Lincoln once again fired McClellan.

Throughout the war, McClellan remained an outspoken critic of Lincoln and his managing of the war. He ran against him for president on the Democratic ticket in the 1864 election. Although the popular vote was close, Lincoln handily defeated McClellan in the Electoral College by a vote of 212-21. That loss proved too much for the vain McClellan, who promptly left the country and did not return for three years.

Although a brilliant engineer and tactician, McClellan clearly was not a battlefield commander. Ironically, Napoleon, whom he admired, was exactly the opposite. The “Little Corporal” would seize opportunities and turn them into victories. McClellan, despite being called the “Little Napoleon,” could not. His rigid mind-set prevented him from doing so, and he gained a decidedly un-Napoleonic reputation for not fighting.

As the author states, McClellan’s elitist upbringing clouded his judgment. He staunchly believed that people such as Lincoln who did not hail from his type of background were inferior to him. It was a fatal flaw in his character, one that would ultimately prove to be his downfall.

The Burden of Guilt: How Germany Shattered the Last Days of Peace, Summer 1914 by Daniel Allen Butler, Casemate Publishers, Havertown, PA, 2010, 336 pp., notes, index, illustrations, $32.95, hardcover.

The Burden of Guilt: How Germany Shattered the Last Days of Peace, Summer 1914 by Daniel Allen Butler, Casemate Publishers, Havertown, PA, 2010, 336 pp., notes, index, illustrations, $32.95, hardcover.

Author Daniel Allen Butler has taken the long-accepted premise that World War I was the combined fault of all the European world powers at the time and argues that it was Germany alone that was responsible for beginning and prolonging the bloody conflict. He firmly believes that the fighting could have been stopped in 1914, had the German monarchy not chosen instead to pursue total victory in the war. Butler makes the added point that the modern world is a direct result of Germany’s choices in 1914.

There is no doubt that by mid-1914 the German Army was ready to go to war. A decade earlier Field Marshal Alfred Graf von Schlieffen, chief of the German general staff, had devised a plan that would seize France and Russia. “Each automatically followed the other in a rapid succession,” Butler writes, “with no allowance for changes in circumstances which might make such attacks unnecessary or even counterproductive—which was precisely what happened.”

Even after Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria-Hungary was assassinated in Sarajevo, war could still have been averted. Kaiser Wilhelm II had suggested that the trouble in the Balkans was a Serbian and Austro-Hungarian issue and that his country would not make a commitment to become involved. A short time later, he reversed his decision and stated that Germany would support Austria-Hungary and crush those who had murdered Ferdinand. This proclamation gave the German Army a blank check, so to speak, and mobilization by all the European powers soon began.

What followed was incomprehensible to the world. Slaughter on a scale never before realized soon erupted throughout Europe. For the next four years, the best of European manhood was wiped away. On the first day of the Battle of the Somme in 1916, for instance, Great Britain alone lost 50,000 men.

When the “war to end all wars” finally concluded on November 11, 1918, the Allies drew up the Treaty of Versailles. The pact humiliated the German people by slicing up their territory, eliminating their navy, and transforming their army into nothing more than a glorified police force. This embarrassment on the world stage infuriated the German people, including one little-known paper hanger in Berlin named Adolf Hitler, who would rise up and lead his nation once again down the same terrible path that his predecessors had followed 25 years earlier.

Seal of Honor: Operation Red Wings and the Life of Lt. Michael P. Murphy, USN by Gary Williams, Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, MD, 2010, 256 pp., appendix, illustrations, $29.95, hardcover.

Seal of Honor: Operation Red Wings and the Life of Lt. Michael P. Murphy, USN by Gary Williams, Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, MD, 2010, 256 pp., appendix, illustrations, $29.95, hardcover.

On June 28, 2005, a SEAL team led by Lieutenant Michael “Murph” Murphy was compromised in Kunar Province, Afghanistan. The New York native and his four-man team had been assigned to kill or capture Ahmad Shah, a Taliban commander who led a group of insurgents called the “Mountain Tigers.” After their insertion, Murphy’s men were accidentally seen by a group of goat herders. After some discussion, the locals were released, which turned out to be a fatal error on the Americans’ part.

After the farmers informed Shah of the SEALs’ whereabouts, a large number of enemy forces converged on their hiding place. A two-hour firefight ensued and the men held off their attackers as best they could. Murphy radioed for help and a MH-47 Chinook helicopter, sent to assist the beleaguered team, was quickly dispatched. Sadly, it was gunned down by a rocket-propelled grenade launcher, killing all 16 passengers. Murphy was killed when he left the sanctuary of the team’s lair to gain a better signal in which to radio for assistance. The lone survivor, Hospital Corpsman 1st Class Marcus Luttrell, made good his escape and was eventually rescued.

Murphy was posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor, and each member of his team was given the Navy Cross, making them the most decorated SEAL team in history. The author has written an outstanding tribute not only to Murphy and his men, but to all those who participated in the subsequent operation that finally eliminated Shah and his guerrillas.

George Washington’s Great Gamble and the Sea Battle That Won the American Revolution by James L. Nelson, McGraw Hill, New York, 2010, 376 pp., notes, index, photographs, $26.95, hardcover.

George Washington’s Great Gamble and the Sea Battle That Won the American Revolution by James L. Nelson, McGraw Hill, New York, 2010, 376 pp., notes, index, photographs, $26.95, hardcover.

The year 1781 was a bleak one for General George Washington’s Continental Army. The British still held New York and had seized Charleston, South Carolina. Supplies were not forthcoming; many soldiers were barefoot and hungry. Recruitment had sunk to an all-time low since the army’s inception six years earlier. Morale had hit rock bottom and some of the regiments became rebellious when their demands were not met.

However, Washington met with French general Jean-Baptiste Donatien de Vimeur, Comte de Rochambeau, and decided on a bold move. Together with the French fleet, led by Rear Admiral Francois Joseph Paul, the Comte de Grasse, American and French troops would make their way to Virginia to bottle up General Sir Charles Cornwallis and his men at Yorktown.

It was a race against time. De Grasse had to stop the British fleet from arriving at Yorktown with supplies and reinforcements for Cornwallis’s command. On September 5, British Rear Admiral Sir Thomas Graves and 19 ships of the line met De Grasse’s fleet of 24 vessels in the Chesapeake Bay. HMS Intrepid let loose a salvo to signal the start of the engagement. By nightfall, when the firing finally ceased, the British had been stopped. Although not a resounding French victory, the outcome was what Washington had hoped. Cornwallis’s men were still hemmed in at Yorktown, with no chance of being resupplied. Cornwallis surrendered his command on October 19, 1781, effectively ending the Revolutionary War.

Nelson gives a vivid account of the events leading up to the sea battle, later called the Battle of the Capes, which helped turn certain defeat into victory for the American forces. By prohibiting the Royal Navy from assisting the beleaguered British troops at Yorktown, the Americans, with the notable help of their French allies, gave birth to a new nation.

The Roman Army: The Greatest War Machine of the Ancient World edited by Chris McNab, Osprey Publishing, Long Island City, NY, 2010, 288 pp., illustrations, maps, $25.95, softcover.

The Roman Army: The Greatest War Machine of the Ancient World edited by Chris McNab, Osprey Publishing, Long Island City, NY, 2010, 288 pp., illustrations, maps, $25.95, softcover.

From its beginning in 753 bc until its fall in ad 527, the mighty Roman Army was feared not only across Europe, but in Africa, the British Isles, and Asia. In his new book, writer Chris McNab has penned a splendid history of the Roman Army, delving into great detail on the uniforms, weapons, and tactics employed by the Romans to maintain their hold on their vast empire.

The author chronologically follows the formation of the legendary force and how it evolved into the superior army that soon enveloped the known world. As with all of Osprey’s books, this one is full of detailed drawing and maps to enable the reader to easily follow the army’s progress from its humble birth to its transformation into the stuff of legend.

“Not only are the campaigns and battles of Rome still studied in depth at universities and military colleges around the world,” writes McNab, “but the power of the Roman

military machine makes it a perennial subject for Hollywood movies as well as publishers. The history of the Roman Army, after more than a millennium of study, shows no sign of losing its power.”

The Untold War: Inside the Hearts, Minds, and Souls of Our Soldiers by Nancy Sherman, W.W. Norton & Co., New York, 2010, 352 pp., notes, index, $27.95, hardcover.

The Untold War: Inside the Hearts, Minds, and Souls of Our Soldiers by Nancy Sherman, W.W. Norton & Co., New York, 2010, 352 pp., notes, index, $27.95, hardcover.

What sparks the imagination of a young person to enlist in the military? Is it merely the romanticized view we sometimes have of war, as displayed by Henry Fleming in Stephen Crane’s American classic, The Red Badge of Courage? Whatever the reason, many of our nation’s men and women who are coming home from the battlefields of Iraq and Afghanistan are also faced with an inner war, a conflict that is sometimes harder to win than overcoming the fear of actual combat itself.

Sherman, who is both a philosopher and a psychoanalyst, does not attempt to answer the question of who is for or against any particular war. Rather, she examines what war does to soldiers, and how they cope with their inner feelings on a day-to-day basis. She interviewed and reinterviewed more than 40 veterans, and their accounts provide a riveting portrait of the moral torment that fighting men and women often keep bottled inside.

The author urges soldiers not to keep their memories locked within themselves, but rather to share them with their family and loved ones so that their transition from war to peacetime can be an easier journey. “It is about the fight to live up to the uniform, and the difficulty of living on after it has been shed,” Sherman writes. “This is what weighs on the psyche of a soldier; these are the frontlines of his personal battles.”

Balkan Breakthrough: The Battle of Dobro Pole, 1918 by Richard C. Hall, Indiana University Press, Indianapolis, 2010, 220 pp., notes, index, photos, $27.95, hardcover.

Balkan Breakthrough: The Battle of Dobro Pole, 1918 by Richard C. Hall, Indiana University Press, Indianapolis, 2010, 220 pp., notes, index, photos, $27.95, hardcover.

In September 1918, the Battle of Dobro Pole, fought in present-day Macedonia, was a huge loss for Bulgaria. The defeat essentially eliminated the country from the hostilities. Plagued by a severe food shortage and a population severely divided over the conflict, Bulgaria was in dire straits in 1918.

Although the Bulgarians had soundly defeated the British and Greeks, a numerically larger French-Serbian force pushed deeper into Bulgarian territory until finally both sides clashed at Dobro Pole. The Bulgarian Army fought bravely but could not halt the Allied juggernaut. At war’s end, Bulgaria suffered further humiliation by granting numerous concessions in the Treaty of Neuilly-sur-Seine, losing much of its territory and paying huge war reparations to the Allies. Bulgaria also sustained horrendous losses during the war—101,224 killed and another 155,026 wounded—for such a small nation.

Historian Richard C. Hall has done a marvelous job of telling the story of a lesser-known World War I battle. He masterfully weaves the intriguing world of politics and the military conduct of the war itself to write a compelling account of a part of the conflict that has been largely overlooked.

Defiant Courage: A WWII Epic of Escape and Endurance by Astrid Karlson Scott and Dr. Tore Haug, Skyhorse Publishing, New York, 2010, 368 pp., photos, $16.95, hardcover.

Defiant Courage: A WWII Epic of Escape and Endurance by Astrid Karlson Scott and Dr. Tore Haug, Skyhorse Publishing, New York, 2010, 368 pp., photos, $16.95, hardcover.

Here is a remarkable book about the courage and survival of a Norwegian patriot in World War II. When the Nazis invaded Norway in 1940, Jan Baalsrud fought the invaders but was forced to flee to Sweden. He eventually made his way to Great Britain and was trained as a commando.

In 1943, Ballsrud and eight other operatives returned to Norway on a top-secret mission to destroy an air control tower. When their clandestine operation was compromised, they scuttled their fishing boat, which contained eight tons of explosives, and climbed aboard a smaller vessel to escape. The Germans quickly sank the boat; Baalsrud was the only survivor. He swam the frigid waters and eventually reached land.

For the following two months, he evaded capture, but at a high cost. His health deteriorated rapidly as he was forced to fend for himself in the harsh winter climate. At one point, he amputated nine of his own toes to stop the spread of gangrene. Sick and barely alive, Baalsrud was finally transported to neutral Sweden on a sled pulled by reindeer. He was flown back to England to train Norwegian agents going back to Norway on other covert assignments, but his frail condition prevented him from taking part himself. Baalsrud died in 1987 after a bout with cancer. His ashes were spread among his friends in his native country.

Grunts: Inside the American Infantry Combat Experience, World War II to Iraq by John C. McManus, New American Library, New York, 2010, 516 pp., notes, index, $25.95, hardcover.

Grunts: Inside the American Infantry Combat Experience, World War II to Iraq by John C. McManus, New American Library, New York, 2010, 516 pp., notes, index, $25.95, hardcover.

“I am convinced that the infantry is the group in the army which gives more and gets less than anybody else,” said noted World War II cartoonist Bill Mauldin.

No truer words were ever spoken. Even today, with the high-tech equipment used in combat, it is still the humble foot soldier who has to endure the horrors of frontline combat. Historian John McManus examines certain battles and military strategy from World War II to the present to give the reader a ringside seat to the experiences of these foot soldiers, be they soldier or Marine.

Of particular interest is the chapter dealing with the Marine Combined Action Program in Vietnam. Although General William Westmoreland touted his now infamous search-and-destroy policy, the Marine leadership was pushing a strategy of winning hearts and minds. Marine platoons were placed in villages to teach the South Vietnamese about weapons, patrolling, and other military fine points that would help them defend their villages from the communists. Although the program had its drawbacks, McManus feels that the “CAPs were the least glamorous but probably the most effective aspect of an ill-fated American war effort in Vietnam.”

This is a superb account of the daily struggles encountered by the most underrated group in the U.S. military—the infantry. Planes, ships, and artillery are essential to any military campaign, but it is still the grunt, with the bayonet affixed to his rifle, who has the dirty job of closing with the enemy to achieve victory.

Search and Destroy: The Story of an Armored Cavalry Squadron in Vietnam by Keith W. Nolan, Zenith Press, 2010, 440 pp., bibliography, index, photos, $30.00, hardcover.

Search and Destroy: The Story of an Armored Cavalry Squadron in Vietnam by Keith W. Nolan, Zenith Press, 2010, 440 pp., bibliography, index, photos, $30.00, hardcover.

There is no doubt that the late Keith W. Nolan was the foremost historian on ground action in the Vietnam War. From his first book about the Marines in Hue City, written when he

was just 19 years of age, Nolan has chronicled the “ground pounders’” war in Southeast Asia with accuracy and truth. Not only does he rely on the official documents, after-action reports and duty rosters, but his meticulous research has led him to conduct numerous interviews with the veterans who served in the many campaigns.

His last offering is no exception. It tells the story of the 1st Squadron, 1st Cavalry Regiment, 1st Armored Division during the 1967-1968 period. The unit participated in some of the bloodiest encounters of the conflict such as the Que Son Valley, Hill 34, the Pineapple Forest, and Cigar Island. Although the squadron performed magnificently, Nolan pulls no punches by relating the uneasy relationship the soldiers had with the villages they operated near, which were under the control of the communists.

Nolan lost his own war to cancer on February 19, 2009. He left behind a dozen books on the conflict, always with the infantryman as the prime focus. He told their story well. Nolan will be truly missed. He was without doubt one of the foremost historians of the war in Southeast Asia.

Valley Thunder: The Battle of New Market and the Opening of the Shenandoah Valley Campaign, 1864 by Charles R. Knight, Savas Beatie, LLC, New York, 2010, 314 pp., bibliography, index, maps, photos, $29.95, hardcover.

Valley Thunder: The Battle of New Market and the Opening of the Shenandoah Valley Campaign, 1864 by Charles R. Knight, Savas Beatie, LLC, New York, 2010, 314 pp., bibliography, index, maps, photos, $29.95, hardcover.

Anyone who knows about the Battle of New Market in 1864 surely has heard of the heroics of the 257 cadets of the Virginia Military Institute who participated in the fighting. When a huge gap developed in the Confederate line, Maj. Gen. John C. Breckinridge reluctantly ordered the VMI students into the melee. The rest, as they say, is history.

However, historian Charles Knight, although praising the bravery and courage of the cadets in his new book, also sets to rest many of the misconceptions about the battle that have surfaced over the years. For example, the VMI cadets captured a single gun, not a battery, in the battle, and they did not seize any battle flags. More importantly, the author gives long overdue credit to the regular Confederate Army units who fought that day as well.

Although the Union forces were embarrassed and soundly defeated at New Market, Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant’s strategy of denying the Rebels use of their interior lines and ravaging the agriculturally rich Shenandoah Valley, dubbed the “breadbasket of the Confederacy,” would ultimately prove successful. When the inept Maj. Gen. Franz Sigel was replaced by Maj. Gen. David Hunter, and Maj. Gen. Phil Sheridan took command of the Federal cavalry in the valley, another nail was driven into the Southern coffin. In less than a year, the Army of Northern Virginia would cease to exist, and the guns would go silent in Virginia. The legend, not always accurate, lives on.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments