By Charles T. Sehe

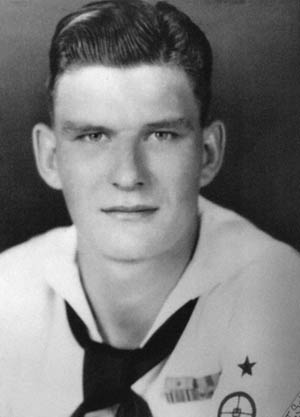

I am of Polish, Irish, and American Indian descent and grew up in the small (population 3,800) northern Illinois town of Geneva. After graduating from high school at age 17 (the only one of six siblings in my family to do so), several of us 17- and 18-year-old kids went down to the recruiting substation in Aurora, Illinois, and enlisted in the U.S. Navy. It was Thanksgiving Day, November 28, 1940—almost a full year before Pearl Harbor.

Applicants had to have been United States citizens between the ages of 17 and 31 and needed to meet the Navy’s physical standards. Since some of us were not 18 years old, parents had to sign for us with their approval. This Depression-era kid stood at five feet, six inches tall and weighed a skinny 127 pounds.

We were allowed to return home for the Thanksgiving dinner weekend. Then, early Monday morning, December 2, a bus drove us from Aurora to the Great Lakes U.S. Naval Training Center near North Chicago, a distance of 60-plus miles.

Once there, we joined another group of recruits to form a company of 110 individuals––Company 122––to be billeted in large wooden barracks where a chief petty officer and two lower ranked petty officers processed us, read us some of the Navy regulations, and assigned us to lockers and bunks. Written and manual exams and physical fitness were also scheduled to determine our qualifications to enter advanced trade schools.

Then we were sent through a processing line where we were issued a complete set of naval clothing: underwear, dungarees, shoes, white jumpers and pants, white caps, etc. Another set of Navy dress blues, caps, and peacoats was issued for winter wear.

Barracks inspection was held every Saturday morning, and each recruit was to have his locker contents neatly displayed on the floor with all clothing tightly rolled and fastened with “stop lines” and small brass ferrules. Some days were devoted to Army-style drills with rifles. We marched around the camp wearing khaki canvas leggings called “boots.” I suppose this is why the Great Lakes Naval Training Center was called “boot camp.”

Reveille was at 5:30 am. We dressed and marched in formation to every meal––breakfast, lunch, and supper. On Sunday, each recruit attended his own faith and worship service. “Rope Yarn Sunday” was free time for all to catch up on seamanship skills, washing clothes, writing letters, or just getting acquainted with the other recruits of our company.

On the rifle range I did not hit anything but got a sore jaw from the weapon’s recoil. I never learned to swim, but I did pass the swimming test by dog paddling my way across the long pool’s required distance.

Final inspection and graduation for Company 122 was January 4, 1941. I had previously developed a sore throat with runny nose—catarrh fever—and was admitted to sick bay. Two weeks later, I was assigned to Company 130, with which I graduated on January 18, 1941.

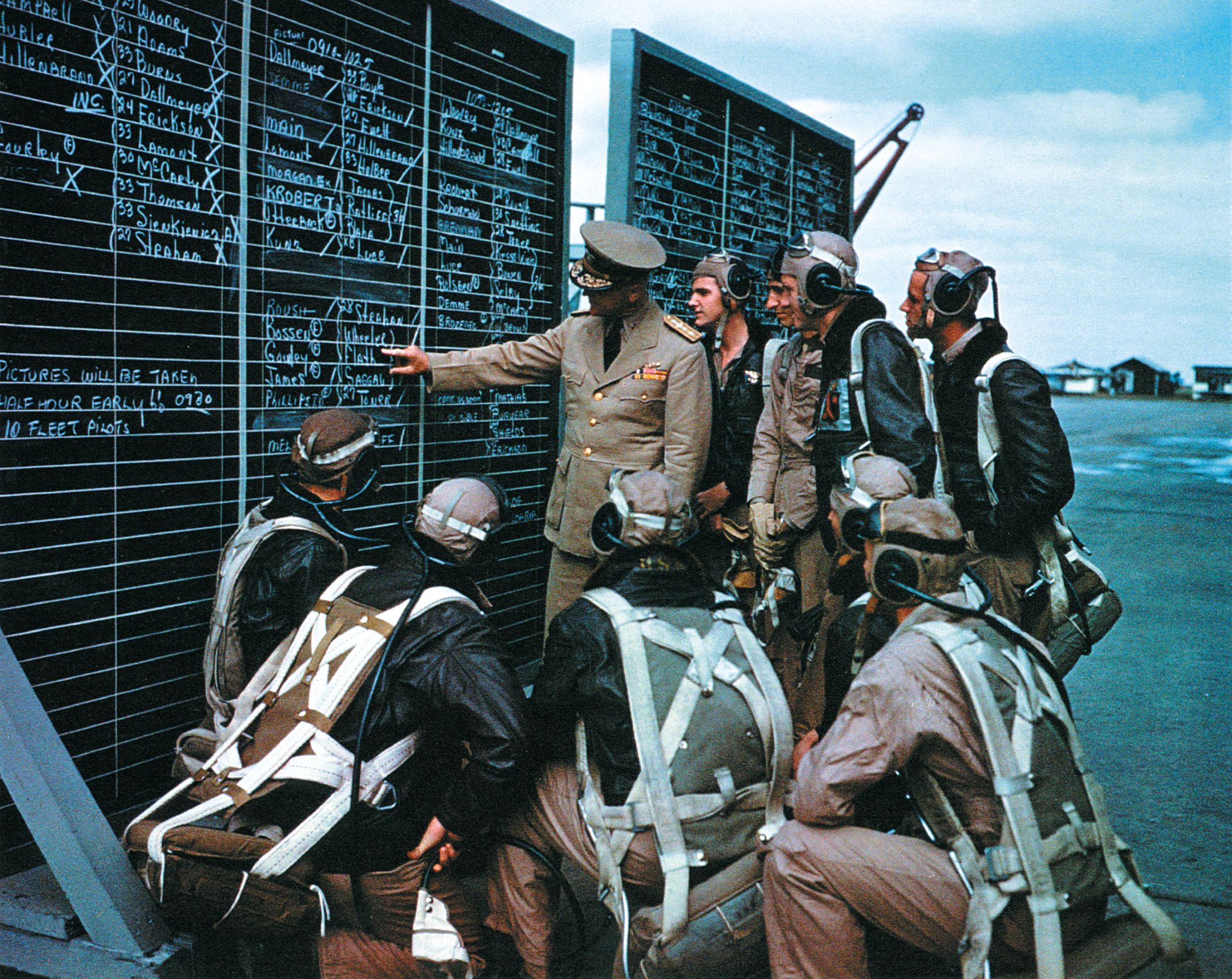

In a large hall our new assignments were given to us by a petty officer stenciling on each recruit’s clear mattress cover the name of the ship or station to which we were assigned. The printed words on my mattress cover read, “USS Nevada (BB36), Bremerton Naval Yard, Washington.” A series of unanticipated historical events soon erupted that would profoundly affect my personal life.

After completing my recruiting duties at the Great Lakes Naval Training Station, I went by train to the Puget Sound Naval Yard in Bremerton, Washington, where I reported aboard the Nevada, a battleship with a crew of 1,500 men. From Puget Sound we would sail to the tropical paradise of Pearl Harbor, Hawaii.

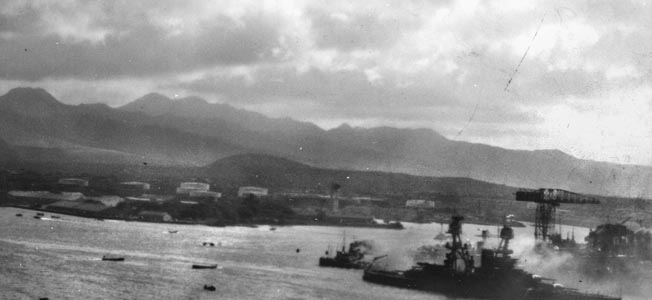

Pearl Harbor

In early December 1941, the Nevada was moored to Quay Fox 8, just astern of the battleship USS Arizona. On the Friday afternoon before that fateful Sunday, I went aboard the Arizona to visit a hometown friend. He invited me to come over on Saturday night after liberty, but I had duty watch on Sunday so I declined his offer. He would be among the 1,177 who perished aboard the Arizona the next day.

At 7:55 am on December 7, a bright, sunny Hawaiian morning, most of the Nevada crew had finished eating breakfast, and the band members and the Marine color guard were assembling on the main deck aft in preparation for the daily posting of the American flag. I left the dining area to use the enlisted men’s “head” and, moments later, the concussions of the first bombs that hit the Nevada literally blew me from my seat.

As general quarters sounded, I ran to my battle station, which was Number 4 After Searchlight, located high up on the mainmast. Already, incoming Japanese planes were strafing the exposed deck areas with machine-gun bullets, and the color guard and band members were scattering for safety. Since the searchlights were obviously not used during daylight hours, all I could do was watch this terrible, alarming, unbelievable nightmare unfold before my eyes.

An aerial torpedo launched from one of the Japanese planes soon struck the Nevada on the port side near frame 40, causing the ship to lurch violently upward and shudder. I could also see numerous torpedo wakes streaking toward the moored battleships West Virginia and Oklahoma.

The Nevada, with some of its boilers already lit on standby, got up enough steam pressure to get underway. As my ship slowly eased its way into the channel and past the Arizona, a tremendous, fiery explosion ripped the Arizona apart, showering the open-deck crews of the Nevada with hot, searing debris, burning many of them to death.

I watched a second wave of high-level and dive bombers now concentrating their efforts on the Nevada as we, the only ship moving, slowly proceeded up the channel, trying to reach open water. Eight bombs hit their mark and severely damaged our forecastle, bridge, and the boat-deck area. The Nevada, I learned later, was given orders to beach herself to avoid blocking the channel and preventing other ships from entering or leaving. An urgent call piped for firefighters—“men free!”

The Nevada now lay bow low aground. I came down from my perch on the mainmast to help with rescue and firefighting efforts and discovered all her decks below the second level, except for the watertight compartments, were filled with floating debris in foul-smelling water mixed with heavy sludge fuel oil.

After most of the fires were put out, we turned our attention to removing the wounded and dead, who were then transferred to motor launches that came alongside. Motor-launch crews were moving between the ships, pulling severely wounded and burned sailors, covered with fuel oil, from the burning waters.

After the attack ended, we were given galvanized buckets to pick up the numerous isolated body parts strewn around the 5-inch gun casemates within my division area. I can never forget finding mangled arms, legs, heads, and knee joints, as well as shoulder fragments and torn, burned body torsos—all unidentifiable because of their blackened, burned condition. The tremendous force of the numerous explosions seemed to have literally strained some of the bodies through the chain-link fencing making up some of the bulkheads in the vicinity of the huge casing for the smokestack.

Seven sunken U.S. battleships now lay helpless along Battleship Row in the harbor. After the fires had been put out and the wounded and dead were removed from these ships, harbor tugs towing empty barges came alongside these stricken vessels to begin salvage operations. Nevada’s losses were three officers and 47 men killed, 102 wounded, and 17 missing.

The Nevada still lay bow down, mired in the mud at Waipio Point. We began throwing all loose debris and metal fragments into the barges while repair crews from the navy yard climbed aboard carrying acetylene torch tanks and began cutting through the fire-blackened, torn, and twisted structures still posing a hazard to the crew.

Raising Nevada

I still recall the day, February 12, 1942, when the bow was slowly raised by a huge barge crane, causing a loud sucking noise as our ship was freed from its muddy prison and floated. Towed and maneuvered by tugs, Nevada reached one of Pearl’s drydocks, where repairs immediately became top priority to make the ship as seaworthy as possible to reach the mainland for more extensive repairs.

The wide, gaping hole on Nevada’s port side, left there by a single torpedo launched by one of the Japanese aircraft, was soon closed tightly by the welding together of numerous steel plates. Those steel plates later became affectionately known as the “million-dollar patch.”

Being a seaman second class, I was among the 300 skeleton cleaning crewmen that remained assigned to the Nevada, whereas the more experienced and high-rated crew members were transferred to other ships for immediate sea duty.

From December through February, we worked during daylight hours removing all debris and, by using gasoline-powered pumps, soon drained the acrid, foul-smelling water and oil from the lower compartments—after which it was determined that it was safe to enter these areas; some had been filled with poisonous fumes.

Every day at dusk, we left the ship by launch for the base facilities where we took hot, soapy showers to remove the grimy dirt and oil from our bodies and have a hot meal. We then were billeted in the Bloch Arena for a good night’s rest.

The Nevada left Pearl Harbor under its own power with me aboard and slowly proceeded across the Pacific to the Puget Sound Navy Yard in Bremerton, arriving on May 1, 1942. The crew was granted a 10-day leave, so I left by train to go home to visit my parents, who were very happy, though shocked, to see me alive and well.

Upon my return to Bremerton, a profound change was occurring in the silhouette of the Nevada’s superstructure, foremast, and smokestack. The 10 casemated guns had been removed, and eight dual-purpose twin 5-inch gun mounts were being installed. These guns were more suitable for defense against incoming enemy planes and could still be used against surface craft using modern electronic fire-control systems and computerized range-finding equipment to provide rapid firing and movement.

I can’t recall the specific day in May 1942, but I was privileged—among hundreds of servicemen and naval yard workmen—to see President Roosevelt’s motorcade course through the navy yard. He had requested to see some of the damage caused by the Japanese naval assault at Pearl Harbor.

From May through June 1942, as the Nevada was being reconditioned, periodic bulletins gave the first indications how grave the situation had become for the Allied forces in the Pacific Theater. Week after week following the initial attack at Pearl Harbor, Japanese successes seemed to continue––Wake and Guam Islands, Singapore, Malaya, and the Philippines were conquered.

The loss of numerous U.S. warships, cruisers, destroyers, and submarines just added more despair to the humiliation suffered at Pearl Harbor. These new, tragic events gave this 19-year-old crewman the horrible realization that we were engaged in a deadly game of war, and this thought sickened me emotionally.

During the second week of June 1942, a communiqué from CINCPAC (Commander-in-Chief, Pacific) gave us most welcome news that spread quickly throughout the U.S. fleet. Navy fliers had sunk four Japanese aircraft carriers in the Battle of Midway. What a morale booster!

Division officers aboard our ship gave encouraging impromptu talks about their respective views on the future. In summary, they emphasized that our naval forces would now have the opportunity to avenge the Pearl Harbor disaster by striking back at the Japanese with more sophisticated weapons of war, modern warships, and tons of military equipment, as the industrial might of America swung quickly to full-time war production.

Upon the completion of the Nevada’s modernization, involving almost eight months of overhaul, our crew of 450 including several Pearl Harbor survivors left Bremerton and set course toward Port Angeles located in the upper straits of Juan de Fuca between Washington State and Vancouver Island. Here gun crews and radar operators began testing their new, computerized equipment. I was instructed in the use of the FD radar unit, assigned to gun director Sky No. 1. Four gun-director mounts controlled the rapid movements and firing of the newly installed twin 5-inch antiaircraft gun mounts, all electronically operated.

In practice runs, a small surface craft would tow a target sled some distance behind it, and these objects would appear as two small, elevated blips on the green radar screen. Repeated practice runs enabled the radar operators to readily distinguish with accuracy between the towing vessel and the target. I also gained experienced as a 20mm gun operator when gunnery practice for all antiaircraft batteries—5-inch, 40mm, and 20mm—became the order of the day.

Operation Landcrab

Cruising southward along the western coast of the United States, the Nevada reached San Diego, then began gunnery exercises again, this time near San Clemente Island, a restricted U.S. Navy reservation some 25 miles offshore from San Diego.

In the first week of April 1943, the Nevada received its orders to accompany two other battleships—Pennsylvania (another resurrected Pearl Harbor casualty) and Idaho—along with several cruisers and destroyers to a chain of islands extending southwest from Alaska, the Aleutians.

As we approached the island chain, the weather began to change drastically from what we had experienced in Bremerton, San Diego, and Hawaii. Dense foggy areas, blustery winds, and snow flurries greeted us as the mountainous islands came into view. A solid overcast prevented any sunshine from breaking through. Winter must come here early, we thought, but in April?

“Air defense” and general quarters alarms often sounded as “bogies” (unidentified aircraft) appeared on the air-surface radar screens. Rough seas, persistent dense fog, driving rain, and sometimes blinding snowstorms postponed the landing at Attu—an island 60 miles long and 20 miles wide—several times and had made those landings difficult for the ground troops once the order was given.

Bombardment by the Nevada’s main (14-inch) and secondary (5-inch) batteries at Massacre Bay eliminated the threat of enemy concentrations massing for counterattacks. American bombers operating from a base at Adak Island were having frequent and dangerous skidding mishaps during takeoffs and landings across water-covered runways. Dense fog, wind-driven rain or sleet, and the constant backlash of propeller-driven fountains of water from the runways often impaired pilot vision. Temperatures often fell below zero degrees Fahrenheit.

The Nevada arrived at Adak on Saturday, April 17, 1943, and dropped anchor in its harbor. We refueled from a tanker before leaving on patrol with two prewar cruisers, the Detroit and the Richmond, and several destroyers. Our position was only a few hundred miles from a Japanese naval base in the Kuriles, so this group of ships was ordered to patrol with a distance of 35 miles between them. Enemy subs were a problem, but several were reported sunk.

My newly learned skill as a radar operator was soon to be tested many times. Bogies often appeared on the green screen. Our AA gun batteries were ready to commence firing if the bogies did not give the correct recognition signal. Our radar was constantly scanning the skies for enemy aircraft during preparation for the bombardment of Attu. The Nevada and the two cruisers opened fire on April 26 and raked the shore and interior highlands with intense fire.

Our fuel and vital stores were soon running low, and the captain set course for Cold Bay, where the auxiliary vessels lay anchored. Arriving there on Friday, April 30, all deck crews began handling the stores as the fueling continued in rough seas, though we were in a harbor. I believe it was here, handling stores on an open deck in sub-zero weather, that my fingers became frostbitten.

Two incidents remain vividly in my mind. First, a call came from Army command that the Japanese had set up a murderous crossfire in the mountain interior: “Can you help?” The Nevada responded with over 50 thunderous salvos that rocked our ship back and forth. This bombardment eliminated the Japanese crossfire and allowed our infantry to advance.

Second, tragically, a desperate, last-minute Banzai charge by a thousand Japanese soldiers on May 29 broke through the U.S. lines in a predawn attack, overran the medical station, and killed all personnel around it––doctors, nurses, patients, everyone. An American counterattack swiftly retook the area and captured some 25-30 prisoners.

Our 27-year-old lady had apparently developed engine trouble during the operation, for she started to groan and shudder; the captain announced that the Nevada had permission to go to Mare Island, near San Francisco, for repairs. We departed Attu on June 7, 1943.

After the repairs were completed, we received orders to steam south, pass through the Panama Canal, and proceed to Norfolk, Virginia, to prepare for Atlantic convoy duty escorting cargo ships, fuel tankers, and other auxiliary vessels to Belfast, Northern Ireland.

All of our numerous Atlantic crossings were successfully completed without a major mishap, but those frequent ocean storms, heavy seas, and the constant threat of German submarines kept all of us on full-time alert status. We soon learned that all of these crossings were bringing vital equipment and supplies for the upcoming invasion of Europe—Operation Overlord.

Operation Neptune

During Operation Neptune—the assault portion of Operation Overlord, the Allied invasion of Normandy on June 6, 1944—the USS Nevada was part of the huge naval armada that stood off the beaches and hammered German defensive positions.

Under the protective umbrella of the Nevada’s gunfire support, Neptune’s Naval Beach Battalion sailors coordinated ship-to-shore communications for the unloading of cargo vessels, the flow of men and supplies at the “Uncle” and “Victor” landing sectors of Utah Beach, controlling the beaching of LSTs (Landing Ship, Tank) and smaller craft, and the dangerous removal of the Germans’ remaining lethal obstacles.

Nevada’s guns were prevented from always firing in a favorable support position, as the seas became congested with incoming cargo vessels and landing craft. Undetected enemy artillery and mortar fire continued until French partisans were able to provide their precise camouflaged locations to U.S. Army personnel, who then forwarded the information to the warships.

Frequent attacks by British warships against German E-boats, patrol craft, and minelayers operating from Cherbourg and Le Havre also soon eliminated much of the German Navy surface threat.

After silencing the guns in the massive concrete casemates near La Madeleine and Les Dunes d’Varreville, Captain Powell Rhea, the Nevada’s skipper, gave the order for the Nevada to close in another 1,100 yards toward the landing beaches. Now the 5-inch twin gun mounts and the quadruple 40mm guns began to eliminate the harassing German fire coming from those mortar and machine-gun pillboxes along the coast.

Our gunnery crews remained at general quarters for over 80 hours, and this prolonged, intensive firing on enemy-held positions weakened the volume of German return fire, enabling U.S. infantry troops, mechanized vehicles, and additional replacements to advance farther in the Utah sector and to thrust southward into France’s hedgerow country.

After 12 days off the coast of Normandy, the Nevada returned to Weymouth, England. We replenished our ammunition, fuel, and critical supplies before setting course for Cherbourg, a heavily fortified harbor bristling with huge 15-inch guns, some mounted on railroad track beds. Although outranged by 10,000 yards, we silenced all.

German shellfire from Cherbourg’s coastal guns straddled our ship 27 times without even one hit. I could actually see and hear those large, whirling shells coming to the end of their trajectory. Several passed over the ship between the masts before they splashed into the waters just yards from us, sending up huge geysers that sprayed our main deck.

Operation Neptune also survived the onslaught of a fierce Atlantic storm, June 18-22, despite the loss of many sections of the artificial Mulberry harbors at Omaha Beach that were urgently needed to expedite the movement of supplies onto the beaches.

Neptune came to a close. It accomplished its objectives with the successful landing of Allied troops in Normandy and the liberation of France’s coastal harbors.

The war was not over. Nevada’s next assignment: southern France.

Operation Dragoon

German Field Marshal Erwin Rommel was right: “We must contain them on the beaches if we are to win this war!” He had realized that the Allies would have complete air supremacy over Normandy.

We had air supremacy for the invasion of southern France in August 1944, during Operation Dragoon. We also had command of the Mediterranean Sea and the landings of Allied troops on the shores of the Riviera went much more smoothly than the landings in Normandy.

The Nevada dueled with German 13.4-inch gun batteries defending the port of Toulon. These guns had been removed from French ships scuttled earlier in the war and emplaced in reinforced concrete bunkers. The efforts of the Nevada—which fired over 5,000 shells—and other ships made it possible for the troops of the French II Corps to seize Toulon.

Return to the States

From the Mediterranean, the Nevada was ordered to return to the United States for an overhaul, refitting, and further assignment. We learned that the navy yards along the Pacific coast would not be fully capable of solving Nevada’s serious gunnery problems––her fractured and protruding 14-inch barrel riflings and a damaged turret mount, resulting from Nevada’s firing of the 14-inch guns during the Normandy and southern France operations.

Consequently, Captain Rhea received orders to leave the area with his escort vessels by the same route that we had come, proceeding to the Norfolk Navy Yard in Virginia.

After a short stay in New York harbor to avoid a hurricane threat, the Nevada entered a drydock at Norfolk on September 18, 1944. The crew was given a 21-day leave while an interesting and unusual event took place. Our 14-inch guns were relined, and the guns in Turret 1 were replaced with tubes salvaged from—of all ships—the Arizona and Oklahoma, both stricken at Pearl Harbor.

The Nevada left Norfolk on November 21, 1944, and sailed south, proceeding through the Panama Canal. After a brief stop at Long Beach, California, we sailed on to Pearl Harbor, where we tied up to Quay Fox 8—the same site where the Nevada had been moored on December 7, 1941.

Off to Ulithi

After two days of loading ammunition of all calibers, the Nevada set course for the Ulithi Atoll, a major naval staging area in the Caroline Islands. We passed through the Mugal Channel and dropped anchor off an island with an unusual name: Mog Mog.

Mog Mog gave us weary sailors a reprieve from the cruise. We enjoyed unrestricted liberty, drank beer, played acey-ducey, drank beer, played poker, drank beer, and had a scuttlebutt session with a final toast of the stateside suds.

Several task forces were formed at Ulithi. We were part of Task Force 54, the gunfire and covering force, which consisted of six battleships (Arkansas, New York, Texas, Idaho, Tennessee, and Nevada), five cruisers (Pensacola, Salt Lake City, Chester, Tuscaloosa, and Vicksburg), and dozens of destroyers and other support ships.

Those of us on topside watched for almost two hours as ships cleared the Ulithi harbor to begin their rampant raids on enemy shipping lanes and the Japanese home islands. This event left an almost empty area in the harbor for our own Fifth Fleet and auxiliary vessels. In contrast to other streamlined battleships, the Nevada, with her grimy, time-flaked gray paint mottled over her hull, had the appearance of an old, tired scrubwoman at the end of her working day.

Officers of the Nevada met for a briefing session on our next assignment: Operation Detachment—the invasion of Iwo Jima. Our ship refueled at Kerama Retto, and we took on 14-inch and 5-inch shells and powder and thousands of 40mm and 20mm rounds.

On February 10, 1945, the task force set sail to a small island none of us had ever heard of—Iwo Jima.

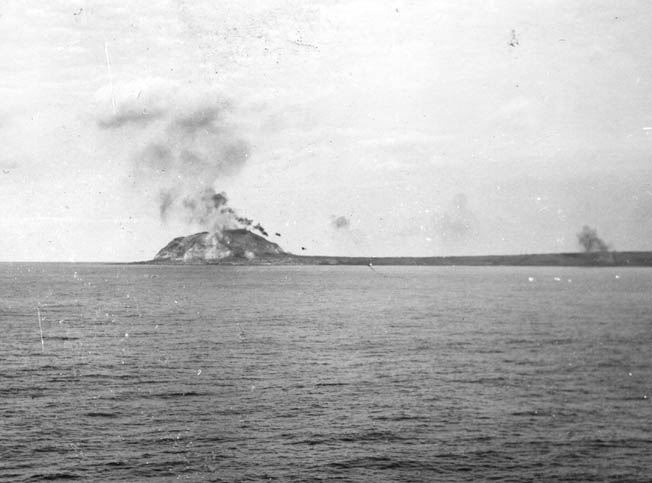

Iwo Jima

Although Iwo Jima was a tiny, obscure island in the Pacific, the United States needed its airfields to be available for crippled B-29s returning from their bombing missions over Japan. The Nevada and other major warships had the responsibility of giving gunfire support to the landing troops who would secure the airfields.

Rear Admiral Bertram J. Rodgers, commander of Task Force 54, made the Nevada his flagship. Rear Admiral William Blandy, aboard the USS Estes, an amphibious force command ship, supervised Task Force 52, which comprised the amphibian support and cover force for the Marines (the 3rd, 4th, and 5th Marine Divisions) that would be going ashore.

The combined task forces arrived off Iwo Jima at 6 am, February 16. My shipmate, Bill Brinkley, was one of the bridge communication talkers who would be monitoring and relaying all confidential messages between the two admirals.

Each battleship had been assigned its time of fire, number of shells, and target areas. Nevada and New York were assigned blockhouses, pillboxes, and any suspicious-looking, sand-covered mounds seen along the beaches. Other warships would fire upon any visible gun battery in the high cliff areas around Mount Suribachi. Priorities were artillery emplacements, blockhouses, pillboxes, and ammunition and fuel dumps.

The preinvasion bombardment was scheduled to last three days (although the Marines had requested more––much more). Personnel aboard Blandy’s ship would record all hits of known targets that the Nevada and other warships counted as having been demolished.

At 9 am, Friday morning, February 16, 1945, we, along with the battleships Idaho and Tennessee, came within a mile and a half of the island and opened fire on the Mount Suribachi cliffs. The Nevada’s role in the invasion was to furnish the main gunfire support for the 5th Marine Division along the “Purple” and “Brown” sectors on the western side of the island near the base of Mount Suribachi.

My general quarters battle station was as gun captain at a 20mm antiaircraft gun mount. On Condition II, I served as an alternate range finder operator during the day and as a radar operator at night.

We pounded the little sulfurous island, five miles long and less than two miles wide but heavily fortified. We destroyed everything on Iwo’s surface but, hell, all of the Japanese were protected by underground, linking tunnels—safe from naval shelling and bombing.

Final reports from the first two days of shelling indicated that the bombardment had scarcely damaged or even reduced the Japanese firepower from the Suribachi batteries. A firm belief by many Navy and Marine personnel at that time was that if Admiral Chester Nimitz had been allowed the original 10 days of prelanding bombardment by the original number of battleships, cruisers, and planes from 12 carriers (taken away from us by General Douglas MacArthur for his sacred Philippines campaign), there would have been considerable reduction in the enemy’s island defenses and, more importantly, a marked reduction in the loss of American lives.

Hours before the initial assault on the beaches began on February 19, a group of LCI (Landing Craft, Infantry) gunboats containing UDTs (Underwater Demolition Teams) came under vicious enemy gunfire. The badly damaged LCI 441 came alongside the port side of the Nevada requesting emergency medical assistance for its personnel. I climbed aboard the 441 with several other sailors and immediately began to transfer the wounded to the Nevada and then returned to remove the dead from its slippery, bloodied decks. It was a horrible sight.

From my position, as the Nevada lay just 2,200 yards offshore, I witnessed the initial landings of the first wave of 5th Division Marines after their LVTs (Landing Vehicle, Tracked) made impressive circles before heading toward the beach. Then the second wave of LVTs made its appearance.

We were told that the defensive organization of Iwo was the most complete and formidable yet encountered. After the initial U.S. naval bombardment ceased in order to allow the Marines to hit the beaches, I felt numb, sick, and, of course, helpless as I watched the extremely accurate Japanese heavy mortars, rockets, and artillery shells from hidden positions rain down a vicious barrage of violent death along the upper beach areas and cut down our troops—a horrifying, nauseating experience watching these men die!

The Nevada was quickly instructed to lay down a rapid rolling barrage of 5-inch high-explosive shells in front of our troops. I could see explosive clouds of dust creeping toward the high terrain just off the beaches that the Marines were trying to reach.

One naval historian wrote, “Battleship Nevada became the sweetheart of the Marine Corps. Her skipper, Captain H.L. (‘Pop’) Grosskopf, an old gunnery officer and a ruthless driver, had set out to make his battleship the best fire support ship in the Fleet, and did. Nevada, when firing her assigned rolling barrage at 0925, found that her secondary battery could not penetrate a concrete blockhouse and turned over the job to her main battery. This damaged a hitherto undisclosed blockhouse behind Beach Red 1, blasting away its sand cover and leaving it naked and exposed.

“At 1100 this blockhouse again became troublesome; the battleship then used armor-piercing shells, which took the position completely apart. At 1512 Nevada observed a gun firing from a cave in the high broken ground east of the beaches. Using direct fire, she shot two rounds of 14-inch, scoring a direct hit in the mouth of the cave, blowing out the side of the cliff and completely destroying the gun. One could see it drooping over the cliff edge ‘like a half-extracted tooth hanging on a man’s jaw.’”

On February 23, I was on the rangefinder watch and witnessed an event that had an intense emotional effect on all Navy personnel on the ships surrounding Suribachi. With binoculars I watched as a small group of U.S. Marines, who had survived vicious counterattacks, raised a small American flag on a long pipe atop the summit of Mount Suribachi. I did not see the second flag raising, made famous by Joe Rosenthal’s widely published photo, as I was then off watch.

Spontaneously throughout the anchorage area, a tumultuous eruption of whistles, sirens, and klaxons sounded in the air. The “whoop, whoop, whoop” of nearby destroyers’ whistles dominated the celebration as the crew members of the Nevada yelled their lungs out.

I also recall Nevada’s periodic star shell barrages, aided by other warships, that illuminated many of the “black night” counterattacks by fanatical Japanese infiltrators. These bursting pyrotechnics sent brilliant, dazzling daylight effects over the darkened island, astonishing this Depression-era kid who had never seen a fireworks display before.

Early on Thursday, March 1, while the Nevada was assisting the destroyer Terry that had been damaged by a Japanese coastal battery, Admiral Rodgers received news that the main U.S. Marine ammunition dump had come under shell fire, causing considerable damage to communication matériel; no loss of life was reported, but several Marines were burned while attempting to retrieve some of the ammunition.

The largest force of Marines ever committed to action in a single battle captured the island after 36 days of unrelenting, bitter fighting. Losses were heavy; the Marines and Navy personnel suffered almost 7,000 killed and over 19,000 wounded, and the 19,000-man Japanese garrison was all but annihilated.

Although the support forces of all services contributed honorably to the final victory, it was the Marine combat teams aided by the Naval Construction Battalions (Sea Bees) and their resources that had to close with the enemy and destroy him.

At approximately 7:30 pm on March 11, back at Ulithi Atoll, I was on black night radar watch on a 5-inch gun director when I heard a swishing noise overhead. I looked out of the open porthole and was astonished to see a twin-engine Yokosuka P1Y “Frances” bomber just passing silently directly over my position. Moments later, all of the Nevada crew topside heard an explosion in close proximity. Reports filtered in later indicating that the newly arrived aircraft carrier, Randolph, had suffered serious damage and 27 dead when that plane slammed into her. It could have been us.

Okinawa

Okinawa was the last epic struggle of World War II in the Pacific. L-Day (Landing Day) was scheduled for Easter Sunday, April 1, 1945. The USS Nevada, anchored in Nakagusuka Bay along Okinawa’s southeast coast, was already being threatened with fiery death and destruction by the daily appearance of Japanese kamikaze planes.

The Nevada and other gunfire support ships moved into their assigned grid units off the beaches of Okinawa, 10 to 12 miles out. The air defense gun crews were alerted immediately to enemy planes approaching. Suicide planes began to infiltrate the antiaircraft barrages and seek out those ships most vulnerable—the carriers.

Think of it! A Japanese pilot crashes his plane onto the deck of a large ship. He sacrifices one life, but he could take out hundreds of U.S. sailors and possibly sink the vessel or severely damage it and put it out of action in one daring moment.

On March 27, at 6:20 am, while at Kerama Retto, a small group of islands southwest of Naha, Okinawa, a Japanese plane (first reported to be a Nakajima B5N1 Kate torpedo bomber but later changed to an Aichi D3A Val dive bomber) crashed into our main deck on the starboard side. The terrific explosion at impact violently strewed twisted 40mm and 20mm guns about and left 60 brave sailors dead, wounded, or missing. The force of one of the explosions threw me against my gun shield but, although momentarily stunned, I was not seriously injured.

At 6:30 on a Tuesday morning, while off the coast of Okinawa, a twin-engine suicide Betty bomber narrowly missed our gun position over Nevada’s stern as it crashed into the sea. Two Japanese crewmen were rescued and brought aboard our ship. Now I saw the faces and stature of my enemy. Both were of small height, bronzed from the sun, and they were approximately my age––both 18 or 19 years of age.

For the next eight or so days our main and secondary batteries pounded the beaches and several inland targets. There was always the opportunity to destroy gun positions that became visible to the shore fire-control parties when given the correct coordinates.

On April 5, during a lull in the daily kamikaze attacks, the Nevada lay 6,000-8,000 yards (three to four miles) off the southwestern coast of Okinawa, alone and not at anchor. Foolishly we remained stationary in position too long, for a Japanese shore battery got our range and sent some 20 salvos toward us. Unexpectedly, water splashes caused by projectiles from that shore battery straddled our ship.

Moments later, five explosions were heard across Nevada’s open deck and structures, which caused moderate damage to the main deck and sleeping areas, two deaths, and several wounded men.

In retaliation, Nevada’s 14-inch batteries unleashed a murderous barrage of shells at the enemy installations, smothering them with fiery debris and rendering them totally silent.

Afterward, several of us walked about and viewed the damage to our ship caused by the Japanese shelling. I picked up a shell fragment while it was still warm. On the base of the five-inch shell fragment was stamped “Made in Maryland.” Obviously, it was part of a U.S. ammunition cache captured elsewhere by the Japanese in earlier times.

Emergency repairs from the shelling were made at Kerama Retto. There we received word that our commander-in-chief, President Roosevelt, had died on April 12, 1945.

By the following day, the Nevada’s gunfire support assignments off the shores of Okinawa totaled 22 days. I believe that we had been at general quarters or air defense some 50-60 times during those 22 days, but it was the brave little destroyers of the early warning picket line that suffered greatly throughout this campaign. It was a bloodbath. On land, sea, and in the air, over 12,000 Americans were killed, 38,000 were wounded, 900 aircraft were lost, 28 ships were sunk, and 368 vessels were damaged.

We were also part of the force that patrolled the East China Sea lanes surrounding Okinawa and Formosa with minesweepers to clear the area for incoming U.S. naval traffic. The Nevada aided a landing force on the tiny island of Ie Shima off the northwest coast of Okinawa that required a six-day battle to subdue. Here on April 18 the United States lost one of its best known GI journalists—Ernie Pyle, killed by enemy gunfire.

While we were patrolling in those waters, our communication center picked up a message from Tokyo Rose: “Hello, Nevada! We know that you are here!”

One day some crew member reported a grinding and scraping noise along the starboard bow and hull—a scraping noise that slowly moved along the ship’s side. Suddenly, someone called out, “Mine chain!” I don’t remember how it was removed, but those few anxious moments certainly prompted me to look toward the heavens and pray.

While patrolling the East China Sea, we had to ride out a slashing storm front at the outer edge of a violent typhoon brewing miles away. Our navigator’s report informed us that the inclinometer read a “roll” of 21 degrees. The Nevada was a 30,000-ton vessel. Imagine what smaller ships like destroyers must have put up with in heavy storms and high winds!

Our ship and several other damaged ships were ordered to report to Pearl Harbor for permanent repairs, overhaul, and updated fire-control systems. Rounding the southern tip of Okinawa, the Nevada joined up with the battleship Maryland, the cruiser Pensacola, and several destroyers and transport ships. We all shared a common tragedy—extensive damage. This small, sad-looking group stopped at Guam in the Marianas for refueling, emergency repairs, and provisions before setting course for Hawaii.

On Friday, April 20, 1945, the Nevada was moored in Pearl Harbor at Fox 3––the berthing site of the battleship USS California at the time of the December 7 attack. We were originally supposed to be repaired stateside, but a shipyard strike was affecting the entire West Coast region.

For two months the days and nights were filled with the blue flames of cutting torches going over the Nevada from stem to stern, and there was the rapid clatter of air hammers and the smell of freshly sprayed paint. Qualified personnel were given liberty and an opportunity for schooling.

Accompanied by two destroyers, the Murray and the Taylor, the Nevada and her refreshed crew finally left Pearl Harbor and arrived early in the morning of June 18, 1945, at the small coral island of Emidj, part of Jaluit Atoll in the Marshall Islands. Our assignment was to harass and silence Emidj, where there was a Japanese garrison, an airfield, and radio tower. The Jaluit garrison was previously bypassed and kept isolated after its neighboring islands, Kwajalein and Eniwetok, were assaulted and taken by U.S. Marines.

The Nevada and her two destroyer escorts divided their gunfire assignments, and both primary and secondary targets on Emidj were quickly ranged and destroyed. The Nevada then withdrew, turned northwest, and stopped at the U.S. base at Saipan in the Marianas. We refueled, took on ammo and provisions, and received orders to return to Okinawa.

Before we got there, however, we were relieved to receive word that the battle for Okinawa was over. On June 30, we joined forces with two other Pearl Harbor survivors, the California and West Virginia, to form a task force with accompanying destroyers and auxiliary vessels to patrol the East China Sea. We went to air defense several times in the Korea Strait.

Going Home

After Okinawa, the U.S. military was apparently reducing the size of the force in the Pacific and discharging some of the prewar enlisted men. I soon learned that I was among the Nevada sailorswho were eligible for transfer back to the States and discharge from the Navy.

On July 31, 1945, I was detached from the Nevada and sent to the receiving station at Kuba, Okinawa, along with a group of other crewmen. On August 5, we boarded the transport USS Kittson (APA 123) and sailed for Guam.

On August 6, while en route to Guam, we received a report that a massive bomb had been dropped over the Japanese city of Hiroshima. A few days later, a second bomb exploded over the city of Nagasaki. The Atomic Age had arrived.

We reached Guam on August 11, where, four days later, we received the most welcomed news: a cease-fire order was in effect throughout the Pacific. All enemy action had ceased by a firm directive of Emperor Hirohito. PEACE! An unbelievable moment for all of us who had survived the war.

The initial end of the fighting in the Pacific had a greater emotional impact on us than the impressive formal Japanese surrender ceremony aboard the battleship USS Missouri in Tokyo Bay, September 2, 1945.

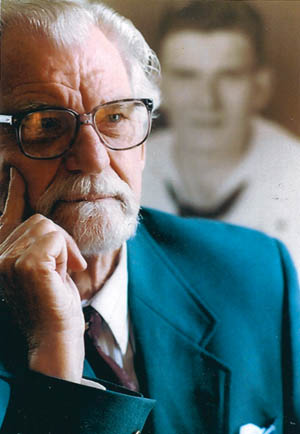

After a short period at Fire Control School in San Diego, I was sent to the Great Lakes Naval Training Center to be discharged on February 26, 1946—my 23rd birthday. I had spent six years in uniform, with three years, eight months, and nine days in combat zones.

I had seen it all—from being at Pearl Harbor when the Japanese attacked to being in the Aleutians and off the shores of Normandy during the D-Day operation, then again for the invasion of southern France to the fierce battles for Iwo Jima, Okinawa, and elsewhere.

After my discharge, I chose to take advantage of the Servicemen’s Readjustment Act of 1944 (the G.I. Bill of Rights) and enrolled in a nearby Illinois liberal arts college. That decision changed the entire spiritual and economic outlook of this Depression-era boy.

Seventy years later, I can’t help reflecting on the fact that young people from various nations entered into this horrific war with different obligations, goals, principles, and ideas. Many never saw their homes again, while others assumed a different life after returning to civilian status. Still others left this war with shattered minds. To many World War II veterans, those terrible moments seven decades ago have become a haunting specter, the anchor of their turbulent thoughts.

Foremost among the many tragedies of war is that it is always the innocent youth to be called to fight, to bear the deepest wounds and scars, and even to die. When will mankind ever learn?

Editors Note: The U.S. Navy deemed the Nevada too old, damaged, and obsolete to be worth overhauling, and so she was designated a target ship for the atomic bomb tests that took place at Bikini Atoll on July 1, 1946. The old girl proved she could still take it. She survived this blast as well as another underwater atomic test three weeks later. Still, she refused to sink, although she was heavily damaged and highly radioactive.

After being towed back to Pearl Harbor and used for experiments in radioactive decontamination, it was decided to use her for gunnery practice. She was towed to a location some 65 miles southwest of Pearl Harbor, where the battleship Iowa and the cruisers Pasadena and Astoria blasted her for over an hour. Although badly battered, she remained afloat. A single aerial torpedo capsized her shortly after 2 pm on July 31, 1948. Her exact resting place in 2,600 fathoms of water remains unknown.

I am working on a children’s book biography of my grandfather, Jack Fox, who was a gunner on USS Nevada at Pearl Harbor, Normandy and all the other battles. His oral history was recorded when he was 78 years old and ailing, so I want to confirm his memories. I have two questions. 1) My Grandpa said that right before Normandy, Eisenhower came on board the USS Nevada and encouraged the troops for the important mission they were about to undertake. I can find no record that General Eisenhower came onboard the ship, but I do have a copy of the letter he wrote to the troops the day before D-Day. Is my grandfather mistaken and the letter was just read to them versus an actual visit by Eisenhower? 2) My Grandpa’s discharge papers indicate he got 4 bronze stars for Asiatic/Pacific and 2 for African-European-Middle Eastern. Did everyone on the USS Nevada receive these or was his for something special? My Uncle, who became homeless, had the bronze star(s) and they are all lost. Thanks so much for any insight. Sincerely, Susan Fox Dixon

Very informative. Great article Iam now 76.never had s chance to fight in a war. Now with nuclear war heads war is now kupit. Thanks for writing it. Perry Soskin @yanks mmp@hotmail.com

Please send me a reply. Thanks

Susan , Dean Rudesill , gunnery mate was aboard in the Pacific. He was a R.E. Agent for my Company in Palos Verdes , Ca. in the 80,s , He told me about a Kamakazi hitting his gun bucket , killing 11 men ! John

This was a great recounting of many pivotal moments in the great conflict. My father was in the Aleutians at the time of the retaking, aboard a mine sweeper. He recalled the conflict with us.

As an ex-Navy sailor, I enjoyed the story on the Nevada very much, always like to read about the enlisted point of view. Thank you !

A great read, thank you!