By Christopher Miskimon

The Winter Line was the German Army’s defensive position in Southern Italy in late 1943. Set into high mountains which dominated the surrounding terrain, numerous Allied attacks against it failed, always with heavy casualties. One of the key positions in this line was Monte la Difensa, held by veteran troops of the 15th Panzergrenadier Division, bloodied in both North Africa and Sicily.

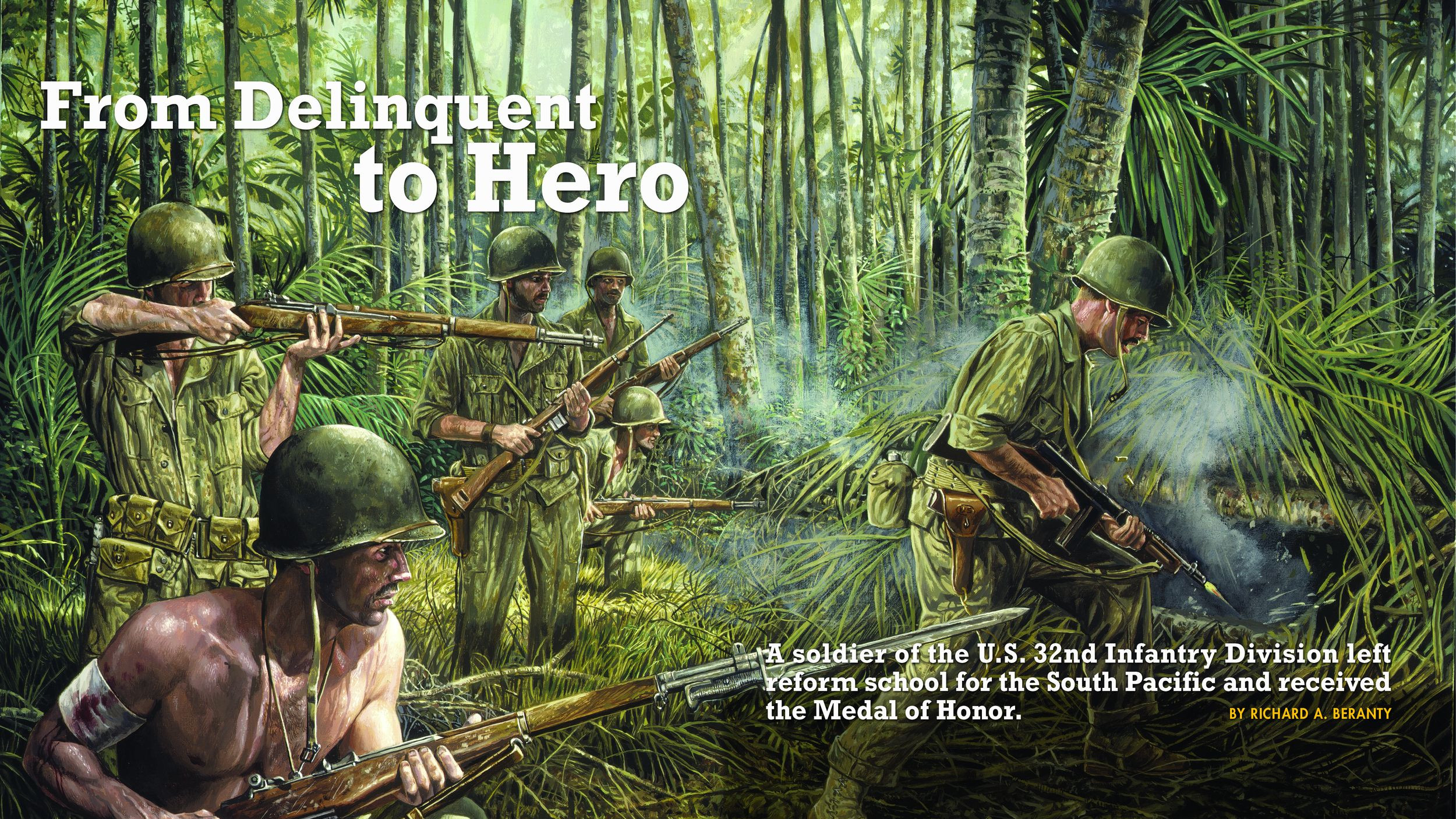

Now, Captain Bill Rothlin, a former metalworker from California, was about to lead 88 men in the first wave of an assault on what seemed an impregnable position. His men took up their weapons, shouldered packs heavy with ammunition and equipment, and began to climb. It was a dangerous mission, and the price of failure would be high, but this was no ordinary infantry unit. These men were part of a new outfit, the First Special Service Force, known colloquially as “the Force,” but soon to be known to the Germans as the “Black Devils.”

Ten days earlier, two “Forcemen,” as they were called, scouted the mountain, looking for a route which would avoid attacking straight into the well-prepared enemy defenses. They found a path around to the northern face of the mountain, where a 200-foot cliff sat behind the German machine-gun nests and mortar pits, which were naturally oriented south toward the Allied lines. The Forcemen were trained mountaineers, able to scale such features. If they could climb the cliff silently, they could surprise the Germans and take a key stronghold in the Winter Line.

Now that plan went into action. Rothlin’s company led the way, followed by the rest of his battalion, a total of 291 determined and well-trained men from both Canada and the United States. As they began their arduous trek up the mountainside, a shell exploded on the German positions above. A British attack was going in at the same time, and the artillery preparation was underway. The bombardment provided quite a spectacle for the Forcemen as they went about their task. Shells roared overhead as 925 guns fired 22,000 rounds in the first hour; the Germans responded with counterbattery fire, adding to the tumult. The artillery likely helped, as it masked the noise of the Allied soldiers approaching the cliff.

The Forcemen started ascending the cliff after midnight. The bombardment was over, and men tried not to make a sound, worried that any clattering rock or squeaking piece of equipment might alert the enemy above. The men’s burdens weighed heavily as they climbed, using ropes placed earlier by scouts. Reaching the top, they eased their packs off while scouts crept forward, searching out a route to the summit 200 yards away. A pathway was found, and the company moved out just after 4:30 AM. They were almost to the top when a German sentry shouted a challenge out into the darkness. One of the Forcemen shot him, and the attack began. Flares lit the night sky, and the ripping noise of MG-42 machine guns shattered the night’s quiet. “All hell broke loose,” recalled one Forcemen, and the battle for Monte la Difensa was underway.

The Force proved its worth in the fighting at Monte la Difensa and served as an example for later elite special-forces organizations. From its humble beginnings as an inter-Allied experiment to its daring exploits on the battlefield, the unit brought together a rough- and-tumble cast of characters and honed them into a sharp commando-style force able to carry out missions few other outfits could. The story of this unique group and its men is well told in The Force: The Legendary Special Ops Unit and WWII’s Mission Impossible (Saul David, Hatchette Books, New York, NY, 2019, 360 pp., maps, photographs, notes, bibliography, index, $28.00, hardcover).

This new work is at heart a battle story, less concerned about the actions of generals and field marshals than about the regular soldiers and junior officers who fought on the battlefield. It is well written, with an engaging narrative, placing the reader among the soldiers as he learns about their origins, training, and combat experiences. The author skillfully blends firsthand accounts, memoirs, interviews, letters, and declassified documents into a readable and interesting story. This book is especially relevant to students of the Italian Campaign, special-operations forces, and those who appreciate a good story of men in the crucible of combat.

Vanguard: The True Stories of the Reconnaissance and Intelligence Missions Behind D-Day (David Abrutat, Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, MD, 2019, 400 pp., maps, photographs, bibliography, index, $46.95, hardcover)

The Normandy landings of June 6, 1944, were the largest amphibious invasion in history to date. If they failed, the repercussions for the rest of the war would have been enormous. Much was riding on the success of the operation, and extensive intelligence gathering was carried out to support it. For example, American signals-intelligence experts cracked the ciphers for the Japanese embassy in Berlin, allowing them to read the message traffic. After the Japanese ambassador toured the Normandy area at German invitation, he wrote extensive reports on the defenses and fortifications in the area. This provided wide-ranging information to Allied planners. There were also numerous reconnaissance missions carried out by special operations personnel, spies, and resistance operatives to learn about the beaches, tidal conditions, German defensive positions, and plans. Together, these thousands of intelligence and reconnaissance specialists gathered the information needed to get thousands of American, British, and Canadian troops ashore and into the fight against the Third Reich.

The author of this new book is a former British Royal Marine Commando and specialist in reconnaissance. He brings this expertise to bear in the book, detailing the various groups and methods used to collect data before D-Day. The work is well-written and contains many interesting photographs, diagrams, and charts from the period, which effectively complement the text.

Generals in the Making: How Marshall, Eisenhower, Patton, and their Peers Became the Commanders Who Won World War II (Benjamin Runkle, Stackpole Books, Lanham, MD, 2019, 435 pp., photographs, notes, index, $34.95, hardcover)

The men who became the United States’ most important generals during World War II were, with few exceptions, largely junior officers in World War I. Between the wars, they often languished in an army the American public generally ignored or even distrusted. Promotions were slow; it was not unusual for officers to spend 20 years in the service and still be a captain or major with limited chances to move further. The Great Depression and the nation’s isolationist tendencies left the army underfunded, and a military career was an almost monastic existence. And yet this small group of dedicated men endured, serving in posts from Washington D.C. to China and the Philippines. They attended military schools together and forged friendships that would later become critical to the war’s successful prosecution. It was a difficult life in many ways, but when the flames of war again began to spread across the globe and the United States was pulled inexorably into another war, men such as Eisenhower, Patton, Ridgeway and Bradley did their duty.

The story of World War II’s American leaders and their pre-war experiences and educations is revealed in great detail in this new book. The author delves into the personal and professional lives of his subjects in a way that reveals how the sum of their lives prepared them for their future. The book provides an interesting look at how officers are prepared, in some ways inadvertently, for the highest levels of command.

Stalingrad: Letters from the Volga (Antonio Gil and Daniel Ortega, translated by Jeff Whitman, Dead Reckoning Press, Annpolis, MD, 2019, 112 pp., illustrations, maps, $19.95, softcover)

The Battle of Stalingrad was a maelstrom of death and horror. Over a million casualties were suffered by the combatants during the months-long struggle for the city. German troops arrived in August 1942, expecting to quickly overwhelm the defending Soviets. Instead, the fighting turned into a slogging, back-and-forth bloodbath, with quarter rarely asked or given. The battle finally ended in February 1943, with the surrender of the remaining German troops, few of whom ever returned home again. The battle was a turning point that destroyed men at an appalling rate.

This new graphic novel tells the story of Stalingrad through the eyes of the German troops who first invaded and later were trapped in the city. It uses letters home from German soldiers as the basis for each story, and as their situation grows worse, the letters gradually become more desperate. The artwork is clear and accurate; attention is paid to uniforms, vehicles, and weapons to make the story look authentic. It also uses actual battle sites in Stalingrad rather than fictitious locations. Since the book strives authentically to portray the horrors of Stalingrad, some of the artwork and language is disturbing and graphic—a novel better suited for more mature readers.

Fur Volk and Fuhrer: The Memoir of a Veteran of the 1st SS Panzer Division Leibstandarte Adolf Hitler (Erwin Bartmann, translated by Derik Hammond, Helton and Company, South Yorkshire, UK, 2019, 256 pp., maps, photographs, $29.99, softcover)

By his own admission, Erwin Bartmann fell under the spell of the Third Reich and joined the Waffen SS at age 17. He thought being in the Leibstandarte Adolf Hitler Division made him part of an elite organization. After training, he was sent to the Eastern Front in late summer 1941. Part of a communications squad, Erwin soon discovered survival was a matter of luck. His luck ran out in July 1943, when a piece of shrapnel pierced his lung at Prokhorovka during the Battle of Kursk. After recovering, he was assigned to the division’s training unit near Berlin as a machine-gun instructor. He was there when the Red Army arrived and fought against the Soviets at Seelow Heights. As the war wound down to its inevitable conclusion, he and some comrades made their way west and wound up as prisoners of the Western Allies.

Erwin’s memoir is a fascinating look at combat on the Eastern Front and the aftermath of the war. Like most Waffen SS veterans, he denies knowledge of the death camps or other activities of the Holocaust and sees himself as a patriotic young man fighting for his country against the scourge of Bolshevism. Unlike most, he acknowledges he did so in the service of an evil regime that was itself guilty of terrible crimes. The translation is smooth, and the narrative is engaging.

Indestructible: The Unforgettable Memoir of a Marine Hero at the Battle of Iwo Jima (Jack H. Lucas with D. K. Drum, William Morrow Books, New York, NY, 2019, 288 pp., photographs, index, $16.99, softcover)

Private Jack Lucas was 17 yexars old when he went ashore on Iwo Jima on February 19, 1945. He joined the Marine Corps at 14, lying about his age to enlist. Now he was in the middle of one of the worst battles of World War II. The next day, he was with three other Marines, engaged in a close-range battle with Japanese troops. As the fighting raged around him, a pair of enemy grenades landed in the Marines’ trench. Lucas jumped on one of the grenades as he pulled the other under his body. The double explosion threw him into the air. There were some 250 wounds in his body; his comrades thought he was dead and moved on. But despite his wounds, he survived and saw the flag flying over Mount Suribachi from the hospital ship Samaritan. He was still carrying 200 pieces of shrapnel in his body after 21 operations. Lucas was also about to become both the youngest Marine and youngest World War II serviceman to receive the Medal of Honor.

This remarkable autobiography was originally published in 2006 but is being rereleased for the 75th Anniversary of the Battle of Iwo Jima. It is a lively tale full of stories from both before and after the battle; Lucas’ life was an interesting one both in and out of the service. The book is written in an easy, simple style, which makes which makes for fast reading.

Cataclysm: The War on the Eastern Front 1941-45 (Keith Cumins, Casemate Publishing, Havertown, PA, 2019, 359 pp., maps, photographs, appendices, index, $24.95, softcover)

The Eastern Front, where Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union tore at each other for nearly four years, was by far the largest continuous theater of World War II. The fighting opened with a massive German invasion by three million troops, which at first seemed to carry all before it. Many thought the Soviets would be next in the growing list of nations ground under the Third Reich’s boot heel. Instead, Soviet determination, the vast distances, harsh weather, and Allied assistance combined to grind the German advance to a halt. Next came the monumental task of throwing the Axis armies back, first out of Russia and the Ukraine and finally to the gates of Berlin itself. Before that goal could be met and the war ended, millions of lives were lost and the future of Europe irrevocably altered.

The Eastern Front was so vast and the battles fought there so large it is difficult for many to fully grasp the enormity of events that made up the fighting there. What makes this book stand out is the author’s ability to take this huge task and condense it into a usable narrative. He successfully describes the war at its strategic and operational levels and creates a manageable history that informs the reader without requiring a multi-volume set or becoming too complex for easy comprehension. A set of useful color maps accompanies the text, and a short but vivid photo insert contains imagery carefully selected to reveal the heart of the war in the East.

Arnhem 1944, An Epic Battle Revisited 1: Tanks and Paratroopers (Christer Bergstrom, Vaktel Books, Sweden, 2019, 400 pp., maps, photographs, notes, bibliography, index, $31.99, hardcover)

Operation Market Garden began as a massive airborne and ground plan to seize a bridge over the Rhine River in German occupied Holland in October 1944. It started with Anglo-American airborne landings to seize the needed bridges. Behind them, the British XXX Corps advanced with its armored formations in the lead, hoping to smash their way through the ground the paratroopers had captured and open a route into the heart of Germany. If successful, the plan could have shortened the war. Tragically, a pair of SS armored divisions had been rotated to the area just before the operation began. This posed a real obstacle to the lightly-armed paratroopers and made XXX Corps’ advance immensely more difficult.

This new work is Part One of a two-volume set on Arnhem by a renowned Swedish historian. It is an innovative work, with fresh looks at a battle which has been extensively written about over the years.

Dispersed throughout the book are Quick Response (QR) codes; the reader can use these to link to various online videos that relate to the book’s subject matter. Most of these videos are original combat-camera footage and films of the battle area. The book itself contains numerous images and maps to accompany the text.

Voices from Stalingrad: First-hand Accounts from World War II’s Cruellest Battle (Jonathan Bastable, Greenhill Books, South Yorkshire, UK, 2019, maps, photographs, glossary, index, $19.95, softcover)

Pulat Gamiyev was a scout in the Soviet Army. During the Stalingrad fighting, his superiors frequently assigned him the job of bringing back a “tongue,” which meant capturing a German who could be made to talk and provide intelligence. During the winter of 1942-43, he was looking for a tongue when he stopped in a village to get hay for his horse. Approaching a haystack, he realized someone was inside. He called out, and four armed Germans came out of the stack. He ordered them to drop their weapons, and they complied; they didn’t realize Pulat was alone. Continuing his bluff, he brought the Germans forward one at a time to search them. Luckily, a Russian soldier happened to come by and helped take the prisoners in; one of them even had a pistol hidden under his uniform. Pulat was recommended for a medal for that day. Instead of one tongue, he returned with four.

Stalingrad was one of the most horrific and intense battles of the war. The author has cleverly taken a chronological account of the battle and woven in numerous personal accounts from over 100 sources, both German and Soviet. Some of the material, taken from German and KGB archives, is published for the first time in this work. There are also a number of rarely seen photographs alongside good maps and a thorough glossary.